Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

In die Skriflig

versión On-line ISSN 2305-0853

versión impresa ISSN 1018-6441

In Skriflig (Online) vol.57 no.1 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ids.v57i1.2960

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Reviewing Calvin's eradication strategy to poverty biblically from a Missio Dei perspective

Takalani A. Muswubi

Department of Missiology, Faculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Most of the marginalised and underprivileged people across the globe live in the vicious cycle of poverty. Poverty is a thorny issue. The World Justice Project (WJP) estimated that two thirds of the world's population are not only confronted by multiple injustices which include the civil, administrative, or criminal justices, but they are also living in a vicious cycle of being marginalised and underprivileged across the planet. The poverty-stricken victims are left hopeless and helpless due to unfair socio-economic and justice systems. Attempts are coming from different fronts on how to eradicate poverty. The researcher realised the two extreme ends of these attempts, namely the rich-oriented capitalist and the poor-oriented socialist extremist. Their debates around poverty tend more to a dichotomy contestation. The question is how can the best of their contestation be utilised for poverty eradication locally and globally. The problem that this article is addressing, is the underlying misconceptions which comes to the fore in the contestation between the rich and the poor in their attempts to eradicate poverty. When such misconceptions are left unchecked, they hinder any attempts or efforts from both sides to obey God's missional call to eradicate poverty.

INTRADISCIPLINARY AND/OR INTERDISCIPLINARY IMPLICATIONS: This article adds the voice (value) regarding addressing the rich-oriented capitalist and the poor-oriented socialist extremist in their attempts to eradicate poverty, conscientizing them that, as they have the same make-up and Maker despite their positions and conditions in life and therefore, based on the ecodomy framework for equitable justice, they should make a conscious decision to eradicate poverty as their missional call before their Maker.

Keywords: poverty; eradication strategy; glocally; John Calvin; Missio Dei.

Introduction

Most of the marginalised people across the globe, who are in the vicious cycle of being underprivileged, are left hopeless and helpless due to unfair socio-economic and justice system. Instead of making efforts to reach and enrich one another in their attempts to address poverty in most cases, the rich-oriented capitalist and the poor-oriented socialist debates tend more to dichotomy contestations. These contestations bring forth underlying misconceptions which, when left unchecked, they hinder attempts or efforts from both the rich-oriented capitalist and the poor-oriented socialist extremist to obey God's missional call to eradicate poverty. The reflection is done within the Missio Dei perspective, considering the creation, fall, redemption, and future consummation themes. Before the conclusion, this article is set to discuss, firstly, the nature of the contestation debate between the rich-oriented capitalist and the poor-oriented socialist extremist; secondly, the underlying misconceptions that hinder the missional call to eradicate poverty, and lastly but not the least, Calvin's ecodomy framework to address underlying misconceptions taking into consideration their common make-up (their positions and conditions in life) and their Maker (who created them all after his image) as the basis.

The nature of the contestation debate

The rich-oriented argument

The negative arguments

The rich-oriented capitalist tends to make negative arguments based on their general view and treatment of the poor. These arguments include the view that poor people are stupid, lazy, disgraceful, and irresponsible people in a society who do not use the opportunities and resources, which are there for the taking, and hence the position and condition of poverty is their own volition. In that regard, they are also accused of the lack of basic management skills (vision, initiatives, and industriousness) and hence they should lay blame to themselves to blame for their poverty.

The positive argument

The rich-oriented capitalist tends to make positive arguments based on their general view and treatment of the rich. These arguments include the view that the rich people are useful people in a society who use the opportunities and resources, which are there for the taking and hence the position and condition of wealth is well-deserved for they saw opportunities and took their chances. In that regard, they manage their resources (money) well. They work hard and smart to achieve their financial freedom, to build their own history (legacy) here and now. Whether they earned their money themselves or inherited it, it is an art to hang onto money and to make it grow. Without them, the economy will collapse, and the poor would starve, for they create jobs and improve their situation (Erasmus 2016).

The poor-oriented argument

The negative arguments

The poor-oriented socialist tends to make negative arguments, including the fact that the rich are thieves who stole thing from poor, The rich are to be blamed for inequality, poverty, unemployment, under wage, working hours, healthy conditions, security in workplaces, child labour etc (Ver Eecke 1996:7-11). The rich do not deserve their money (mostly in the form of land and labour). Everything they have was stolen from the poor class (the most valuable and honourable society members) (cf. Erasmus 2016). The privileges are kept out of jail, earn less sentence and/or have access to medical care.

The positive arguments

The poor-oriented socialist tends to make positive arguments, including the fact that the poor are the most valuable and honourable people in the society. The society is kept going by the work of the poor working class. The rich could not survive without the work of the poor; yet they get not only minimal (financial) reward, recognition, or acknowledgement for their contribution in the society (cf. Erasmus 2016).

Misconceptions about God's will in human life

Moralistic and/or merit-based misconceptions which misread God's justice (theodicy)

There are two distinct basic presuppositions regarding how people interpreted and still interpret God's justice of God or theodicy (Greek words Θεός Τheos and δίκη dikē), namely Firstly presupposition: 'If you sin, then you will suffer'; and Secondly presupposition: 'If you suffer, then you have sinned'.

The first presupposition is a generally and biblically correct (cf. Dt 28). The second presupposition is a wrong view of God's justice. It presupposes, on one hand, that all suffering (poverty and sickness) is rigidly and mechanically a result of God's disproval and curse, and, on the other hand, that the wealth and health is a result of God's approval and blessings. The proponents of the second presupposition including the Judaism legalists and the prosperity gospel preachers have an egocentric (personal) and moralistic (merit-based) mind-set which disregard both God (his Word) and others in this regard (cf. Gn 9:5ff.; Dt 1:17; Hab 1:7). In the book of Job, for example, Job agreed with the first presupposition. However, Job spoke of being just and righteous which does not mean a moral perfection (sinless), but God-imputed righteousness). Job knew of his sin within his heart and agreed with Bildad that no one can be righteous before God (cf. Job 7:21; 9:2; 12:4; 13:18-23, 26). He reacted against the second presupposition which implies that all sufferings are explained by sin. Dillard and Longman III (1994:203) argued that Job's three friends represent the second presupposition, and hence assume that Job is suffering because of sin (cf. Job 4:7ff.; 8:11ff.; 11:13ff.; 18:5ff.).

Secularising the God-willed earthly call

The God-willed sabbatical call for the cancelling of debt was secularised to avoid the (earthly) socio-economic realities and challenges which are part and parcel of the God-willed sabbatical call (cf. Dt 15:1-2). The Jewish initiated prosbul procedure, for example, is a legal court procedure (cf. Greek, προσβολή, meaning, 'in front of the court'). It was introduced by Hillel the Elder (born in Babylonia in 110 BC and died in Jerusalem in AD 10). It was started to make it easy to collect the loan or debts of the powerful and/or the wealthy creditors or moneylenders who were reluctant to obey the Sabbatical call for debts cancelling or release (forgiving) on the seventh year (cf. Dt 15:1-2). The prosbul permit the secular court of law to continue to collect the loans from their debtors on their behalf to bypass the Shemittah call for debts cancelling (forgiving) and to stop the credit market so that subsistence loans for the poor dried up in the sixth year (Lowery 2000:41; Trocme; Nonviolent 29). The main point here is that, by this prosbul practices, the religious sabbatical call was secularised to avoid earthly socio-economic realities and challenges which are part and parcel of the sabbatical call.

Spiritualising the God-willed earthly call.

When debt, an earthly reality, is spiritualised, it is to avoid or postpone its (earthly) socio-economic reality and challenges. For instance, in Matthews 5:3, 'the poor in spirit' is usually spiritualised to escape its socio-economic challenges, including poverty alleviation. The poor in spirit is someone who has no resources (both material and spiritual). In such a lowly and vulnerable condition, state, sphere or sense of bankruptcy and dependence, he or she is led or tuned to begging either from God or from others. It is in such a vulnerable state that God in Christ is concerned about their need for holistic good news for their spiritual and material needs (cf. Mt 11:5, 19:21; 25:31-46). To him, justice should be done by Christians who are not only the citizens of God in Christ their King, but who also experienced and know his law of love - the law that knows no boundary and whose target include loving even the enemies (cf. Lv 19:18; Mt 5:17ff.; 44ff. cf. Ps 86:1).

The Medieval and/or castle mentality

The Medieval and/or castle mentality is the belief and the worldview which urge that one's class and status is pre-determined and pre-decreed by divine will. People are encouraged to disregard, if not belittle, their past and present realities. Together with the Platonic or dualistic view, the medieval and/or castle mentality encourages people to pursue their spiritual realities as their only eternal destiny and goal of life (cf. Hodges 2010:4). Together with the Stoics views, this medieval and/or castle mentality argue that the rich and the poor should submit themselves to and accept the rigid socio-economic class and status as a pre-determined or pre-decreed destiny at birth for their varied eternity, despite who one is and could be (potential) in terms of gifts, (talent or initiative). On the one hand, those who are born into high socio-economic class and status (including the rich, ethnic or racial class and status) are to enjoy the privileges of who they are (their nature) as God's unchangeable and unquestioned will and, on the other hand, the poor are neither to question nor seek fair share, decent wages or to improve their social status. Hence, it is commendable (for the poor and the needy in particular) to have apathy (lack of passion and emotions) as one of their virtuous. In Colossians 2:16-23, Paul also argued against such a mentality, including the Platonic-Stoics teaching (Hodges 2010:4).

The charity (self-righteous grand-standing)

Charities per se is a commendable initiative, but the hand-out charity alone cannot move and direct vulnerable people to liberty. It is only a starting point (a drop in an ocean) of their many and diverse needs. There are many underlying misconception concerning charities which should be uncovered and rooted out. They include the misconception regarding the use of charity to substitute socio-economic justice. It is easier to give money to charities and keep a distance from the poor.

I had come to see that the great tragedy in the church is not that rich Christians do not care about the poor but that rich Christians do not know the poor … I truly believe that when the rich meet the poor, riches will have no meaning. And when the rich meet the poor, we will see poverty come to an end. (Calvin 2006:113)

Caring is deeper than just taking care of the person's immediate (basic) needs; it involves taking care of the whole person and his or her spiritual and socio-economic needs, including Justice (not the substitute for justice). Charity is and should be relational. It is about love. It is not to be used for self-righteous grandstanding (selfish) motives and events. It is not only an event, but a living reality; not to be done and dusted, but as a way of life (cf. Mt 26:11; Harris, 1996:36, 42, 48; Sider, 2005:178ff.). There are problems associated with charity, which is used as a substitute for social justice, including the fact that, firstly, it entrenches and/or perpetuate socio-economic injustice and inequality in the society without being bothered, getting involved or committed in address, or breaking up with the root causes of it. Secondly, it gives the misguided impression that the helper has dealt with a socio-economic problem (poverty), even if the vulnerable are left without being empowered so that their positions and conditions of dependence is uplifted or restored to regain meaningful standing and participation as the member of their own families and community.

Calvin's poverty eradication framework

The socio-economic context in Geneva

'For Calvin, the world was to be taken seriously, and for him, the real world involved shoemakers, printers, and clockmakers, as well as farmers, scholars, knights, and clergymen' (cf. Graham 1971:91).

In his book, entitled Calvin's economic and social thought, the Swiss theologian and economist, Biéler (2005:122-157, 423-454) also analyses the socio-economic reforms during the Calvinist Reformation. The prevailing conditions in Geneva include the following two main influxes: firstly, the overcrowding of refugees and foreigners in Geneva from other parts of Europe, including Italy, France, England et cetera. It led to the shortage of the basic necessities (food, clothing and shelter). Secondly, the influx of the precious metals, including the gold and silver from the west coast of Africa through the Portuguese's conquest and from Mexico through the Spaniards' conquest into Europe, led to the monetary revolution and currencies depreciation as well as the rise in prices of good, dubious business practices, gambling, et cetera (cf. Biéler 2005:129). Calvin apparently witnesses the social equilibrium and solidarity of Geneva residents during his time. The church in Geneva was put under severe stress, as the emerging elites were becoming richer and richer while the majority remain poor with the lack of necessities such as food, clothing, shelter, and decent wage (cf. Biéler 2005:129). The context of the Reformation refugees from neighbouring countries and the question of how to transform the socio-economic life to the fullness of life in Geneva, apparently pervades Calvin's thinking and teachings (Graham 1971:60). In that regard, Calvin used not only the pulpit to address the socio-economic injustices in general (cf. Busch 2007:74), but also the state policies to lobby the state to raise funds in order to help the poor and the needy in particular (Biéler 2005:129)

Calvin sought Scripture to address the socio-economic issues

To apply the gospel to the fullness of life in all aspects of life of all people, Calvin sought the guidance of Scripture in social issues (Biéler 2005:129) not only to bring about societal transformation by both combating the socio-economic imbalance and inequality between the rich and the poor in Geneva, but also to call the rich and the poor to church to live together in a family of brothers and sisters in Christ in order to reflect the glory and justice of God (cf. Busch 2007:74).

Calvin link poverty eradication with God' sovereign rule

Based on creation right, humanity was given the cultural mandate and an ecodomy call to build God's household in all aspects and/or areas of life (cf. the Greek words οίκος [a house]; δοµέω [to build]). In this regard, God's household means his universe and that everything in the spiritual (religious) and in the secular (worldly) realm belong to the triune God (cf. Ps 24:1; Rm 8:19-25). In that regard, the whole inhabited earth (cf. the Greek word oikoumene) lives before God (coram Dei) every day or moment in every aspect, including the socio-economic aspects or sphere of life - all is under God' s sovereign rule (Jn 10:10; Bouwsma 1988:191ff.; Graham 1971:60; Conradie 2011:118; Calvin's Sermon No.45 on Dt 4:26ff.; Gamble 1992:108; Hall 2010:218; McKim 1984:175). By reading Calvin's Sermon No. 45 on Deuteronomy 4:26ff., it becomes clear that it is by God's sovereign will that Christians are called not only to respond towards four basic relationships, namely towards God, towards oneself, towards others and also towards nature, but also to live in paradox (tensions): they live in the world, yet not of the world - to live as citizens of this world and as citizens of heaven (cf. McKim 1984:306; Torrance 1956:121). Calvin's Sermon No. 45 on Deuteronomy 4:26ff., indicates that God called individual Christians and a corporate church as agents to extend Christ's reign of transforming oneself (inwardly, spiritual, and personal) and others (outwardly) in all of life, including the socio-economic (humanity) and environmental (nature) transformation (cf. Bouwsma 1988:191ff.; Gamble 1992:108; Hall 2010:218; McKim 1984:175). According to McKim (1984:305), Calvin (cf. Inst. I.13.6), indicated that what separates godly from worldly people is the faith and the attitudes in response (obedience) to God's word and promises concerning both the body and soul in this present world and in the renewed and future (eschaton) world. The economical and harmonious working of the Trinity (unity in diversity of each person in the Godhead), whereby the Father is the Source of life and all blessings, the Son of God the mediator and saviour of sinful people, and the Spirit of God the source of sanctifying and empowering power (cf. Gn 1:26; Mt 28:19; Eph 4:5; cf. also Selderhuis 2009:248).

John Calvin's five aspects within his whole collection are summarised and discussed

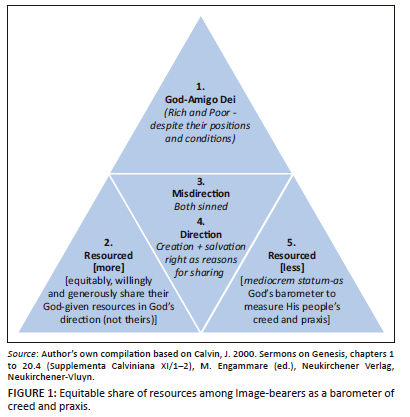

In this article, the topic of poverty and slavery is discussed, using Freudenberg (2009:158-161) who discussed the five aspects regarding Calvin's view on poverty and slavery uncovered in his collected work from 1531 to 1564. In this article a particular focus is on Calvin's 200 sermons preached between Wednesday the 20th of March 1555 to Wednesday the 15th of July 1556 based on the book of Deuteronomy named Calvini Opera Omnia (CO), 28.190 (collected work between 1863-1900) (cf. Calvin, 1583). John Calvin's five aspects within his whole collection are summarised and discussed. The first aspect is that we belong to God and to each other, whether rich or poor. The second aspect is that our being and belongings are God-given and need his guidance (terms and conditions). The third aspect is that sin separated and misdirected four relationships, namely relationship with God, with oneself and others, and with nature. The fourth aspect is that we are of the same make and belong to the same Maker. This fact is the basis for a just and right view and treatment of each other. The fifth aspect is that sharing is a practical test or barometer of and for one's creed and faith. These five aspects are illustrated in the Figure 1 below as well as the subsequent discussion.

The rich and the poor belong to God and hence to each other

[W]e have a common Creator, that we are all descended from God; then that there is a similar nature, so that we must conclude that all men, however low their condition might be and however despised they might be according to the world, nevertheless do have a brotherhood with us. Therefore, he who does not bother to acknowledge a man as his brother, must make himself an ox, or a lion, or a bear, or some other wild beast, and so renounce the image of God which is imprinted in us all. (cf. Calvin CO 34.655).

According to Calvin, the humanness and moral integrity, that is, the morally correct thinking and behaviour of Abraham and Job was based on the Imago Dei whereby humans view and treat each other based on the belief (and worldview) that we are of the same make and Maker. Such understanding shines through in their treatment of slaves: both had slaves as a common accepted custom of their day. They, nevertheless, treated their servants as paid workers and they refrained and/or restrained themselves from following the expected human standard and/or law according to which the masters were tyrants and abusive with power and the right of life and death over their servants, without accounting to anybody (cf. Calvin's sermon on Job 31 [CO 34.654-657]; Calvin's sermon 54 on Gn 12:4-7 apparently inspired by Augustine 1960, vol. XIX, ss. xv-xvi; Calvin 2000:601ff.).

Our being and belongings are God-given, and God guided in his terms and conditions

'All the blessings we enjoy have been entrusted to us by the Lord on this condition, that they should be dispensed for the good of our neighbours' (cf. Inst. 3.7.5; Calvin in his Sermon no.113 on Job 31:13-15, CO 34.647-660).

Humanity's vocation [wealth etc.] is not for power and private use, but for sharing with the fellow (poor) for common good/to promote equality/restore solidarity in and outside the Church (body of Christ). (cf. Calvin's Commentary Ac 2:42ff. 13:36 transl. Graham 1971:68; Inst. 2.8.55)

In this regard, God-given riches in terms of money and goods are not to be used as instruments of power, avarice, miserliness, high-handedness, and a lack of gratitude, but as instruments of human solidarity, advancement and for common benefit and good (welfare) for all (cf. Ac 2:42ff.; Calvin's Commentary Ac 13:36, transl. Graham 1971:68; Inst. 2.8.55). In that way, the rich and the poor are to place themselves in each other's shoes and hence relate and respond to each other's need. To Calvin:

Let those, then, that have riches, whether they have been left by inheritance, or procured by industry and efforts, consider that their abundance was not intended to be laid out in intemperance or excess, but in relieving the necessities of the brethren. (cf. Sermon 95 on Dt 15:11-15, [CO 27.338]; cf. transl. Graham 1971:68; Busch 2007:74; cf. Inst. 2.8.55)

Actions would leave even the pagans and the unprivileged people without excuse as when they display humanity and rectitude (morally correct thinking and behaviour based on Imago Dei) as Abraham and Job did (cf. Calvin's sermon [CO 54.523, 527] on Paul's letter to Tt [2:6-14]). We should show humanness, generosity in relating and responding to each other's need. Calvin was concerned about socio-economic justice (including the poor) and ecological matter (cf. Calvin's commentary on Gn 6:6; Ex 16:19 and on Ps 104:31; Biéler 2005:129; Nyomi 2008:29; cf. also Commentary on Jn 3:17 [CNTC 12.277]). Practical doctrine is to be practically lived and it is from that basis, that fraternal relationship and communion can be built.

Sin misdirected God's directive in our gift-sharing

'The light in man's conscience is imperfect and unable to read this law correctly and hence need special revelation' (Dabney 1985:353). 'The aim of the broad law is to render human inexcusable and to prove them guilty by their own testimony on issue of injustice.' (Inst. 2.2.22; 4.20.15ff.)

The church should look critically at the tendency of the rich-oriented economic systems, namely to justify the sinful human nature such as personal ego, self-interest, pride, greed and selfishness which is seen in grabbing and accumulating great heaps of wealth on the expenses of the vulnerable (the poor) (cf. Preston 1979:91-95). In this regard, the church should analyse the basic nature of the laissez faire free market system, especially the 'freedom to follow human desires' (cf. French word, laissez [to let] faire [to do]; cf Latin laxus [loose], facere [do]; cf. Collins English Dictionary 2012).

The rich and the poor have same make and Maker

[W]e were all made from the same material (matrix)-all descended from Adam, we all pertain to the same nature-brotherhood. However low their condition might be or despised acc. to the world, nevertheless do have a brotherhood with us. Therefore he who does not bother to acknowledge a man as his brother, must make himself an ox, or a lion, or a bear, or some other wild beast, and so renounce the image of God which is imprinted in us all. (cf. Calvin's sermon CXIII on Job 31:13-15 [CO 34.647-660])

Based on the same (common) make and Maker, all human beings are expected to respond and account to God on how they view and treat each other. In this regard, even other masters are expected to view and treat their male and female servants with respect, including granting them the right and the opportunity to plead their good cases and grievances openly and freely (cf. Job 31:13-15).

Sharing is a practical (barometer) test for one's creed

God sends us the poor as his receivers and hence serve a positive function in God's overall scheme of things. To give the alms to mortal creatures, yet God accepts and approves them and puts them to one's account, as if we had placed in his hands that which we give to the poor. (Sermon 95 on Dt 15:11-15 [CO 27.338]; cf. transl. Graham 1971:69).

To him, the poor are like a barometer of the faith or conduct of the Christian community. By granting the poor of the poorest the loan without interest, the faith community are making a faith statement. It is the hallmark of their creeds (confessions). It demonstrates how they view and treat the poor. In this regard, the poor are like the barometer of the faith community as to whether they understand the nature of their own freedom, forgiveness and/or release as slaves and beggars who once stood with empty hands before God and, by his mercy, granted freedom to enter a new sphere of rule and life from the old life of poverty and slavery in Egypt (symbol of sin, Satan and death). With such understanding they are expected to release, free and/or forgive other victims of both the spiritual sins (root cause) and the material debts (the effects). It is in the same sense that Zacchaeus viewed and treated the affected victims under his watch and hence paid not only for a double of stolen amount, but also for the recovered property (cf. Lk.19:8; CO 46.552; Freudenberg 2009:158-161; Preston 1979:91-95). According to Calvin:

The cries of the poor (must) rise up to heaven, and we must not think to be found without guilt before God … Otherwise the rich would rebel against Godself should they disregard the rights of the poor and did not respond humanely to situations of injustice. Compassion with the poor thus becomes the hallmark of humanity for the rich. One is humane when one does justice to the poor (reveals a soft spot for the poor). (cf. CO 28.190)

The summary

The common make (all human) and Maker (Source of life for all)

All people, whether they are the Jews or the gentiles, rich or poor, men or women are of and have common make (as God's image bearers) and Maker (God) (cf. Nyomi 2008:29). The common make and Maker is one of the main basis for the four main relationships, namely Godward (vertical), personal (inwards), towards others and toward nature, but also mitigate, melt, leaven and permeated even the enemies of God's kingdom (Bouwsma 1988:191ff.; Hall 2010:218; McKim, 1984:175). The two-fold love is to lead all people to think (heart), say (head) and do (hands) everything in love and dignity, including to view and treat the poor and bond servants as fellow or fraternal human beings (cf. Gl 3:28; Col 3: 22-4:1; Eph 6:5-9; Rm 6:5-7, 16-18; Heb 2:14ff.; 1 Cor 6:20; 7:21-23; 2 Pt 2:1; Brueggemann 1977:61; Davis 2003:127; Harris 1996:79; Sider 2005:68; Tidball 2005:296; Wenham 1979:317).

The common sin and its spiritual and physical effects were addressed by Christ

Moses' call (cf. Ex 9:1; Lv 25:10) and Isaiah's call (cf. Isa.58:5-6; 61:2) is confirmed, amplified and/or fulfilled by Jesus Christ (cf. Luke 4:18-19; 24:47; Freudenberg 2009:160-161). In Matthew announced Messiah' arrival after the Israelites failed to execute the Jubilee (gospel) call. In Luke 4:16-19, Jesus announces not only His arrival as the promised Messiah, who will fulfil the jubilee call (cf. Lev.25; Is 61:1ff), but also his inclusive liberation in terms of composition. This composition includes restoring people's whole lives, spiritual and physical in and outside the Church (cf. Acts 2:43ff, 4:32ff). In response to Christ and His call, Christians are to realise that sin and its effects which made them enemies of God and not willing and able to serve God (cf. Rom.8:7) is conquered so that they can serve Him while addressing spiritual and physical needs in and outside the Church, including misunderstanding regarding Church composition of Jews and Gentiles, master and slave and men and women (cf. Lk.4:28ff; Gal.3:28; Lowery 2000:9; Weinfeld 1995:65,170).

Jesus's missional call fulfil the three motifs that reveal who God is, says and does!

The inaugural message of Nazareth is both a point of arrival and a new point of departure. The kingdom is not only past event and future hope; it is present task and celebration - inauguration. (cf. Arias 1984:47).

The great revolutions of our time are an effort to redistribute land back into the hands of those who lost it. ….. to redistribute land according to tribal conventions that have been gravely distorted in the interest of concentrated surplus. (cf. Brueggemann 1977:193)

Jesus fulfilled the three motifs, namely, the creation (Imago Dei) motif, the Exodus (covenant) motif and Deuteronomic motif. Creation motif, remind all human beings are created in God's image. We have the same makeup (identity) and the same Maker (origin). Such creation rights, gives us dignity, responsibility, and accountability to love and live before God and hence to provide and protect humanity and the rest of creation (neither exploit nor oppressed those who are in the vulnerable position and condition like poverty and slavery (Mtt.5:48; 6:21,24; 10:42; 18:6; Col 1:18b; Bouma-Prediger & Walsh 2008:12, 24; Bouma-Prediger 2001:234). Covenant motif, remind us (cf. the preamble in Exo.20:1-2) that the Israelites (and the Church) are not only freed, saved, and called from slavery in Egypt (from in sin) to be in covenant relationship with Him, but also equipped with gifts, privileges and resources, to be God's agents to view and treat other human beings as the potential recipients of God-given redemption (salvation and/or deliverance) (Exo. 3:8; 5:23; 6:6; 18:4,8-10; 20:1; 22:21; 23:9ff). The Deuteronomic motif remind us (cf. the preamble in Deut.5:1-3) that the Israelites (and the Church) embodied the creed (what they believe) to be not only to consistently and repeatedly recited and/or relived the recorded creed (confession), but also to use it as a guide of faith and life (conduct), as a way of showing gratitude to and of glorifying God (cf. Deut. 5:14; 6:12; 15:15; 16: 9-17; 11; 23:15f; 24:17ff; 26:11; 28:43; Jud. 6:9; Mic. 6:4; Harris 1996:61).

Jesus's liberation incentives offer a platform and opportunity equitable justice

Jesus's liberation incentives offer a platform and opportunity (time) of and for atoning unity, reconciliation, and relationship which not only begins with God, but also embodied by us as we reflect God' s favours towards each other, especially towards those who are disadvantaged and marginalised.

Jesus's missional role which was prophesied throughout the scripture are the basis for Calvin's ecodomic theology stated in this article. Its theological argument is important in the Church and in the society, otherwise they will be robbed of triune God's gospel call which remain a need even today in the socio-economic and political (and polarised) context of South Africa and beyond.

Conclusion

This article adds the voice (value) on addressing the underlying misconceptions emerging between the rich-oriented capitalist and the poor-oriented socialist extremist debates in their attempts to eradicate poverty. Poverty remains a thorny issue. The poverty-stricken victims are left hopeless and helpless due to unfair socio-economic and justice system. Endless attempts coming from different fronts on how to eradicate poverty are not helping unless the dichotomy contestation is addressed. When such misconceptions are left unchecked, they hinder any attempts or efforts from both sides to obey God's missional call to eradicate poverty. The question is how can the best of their contestation be utilised locally and globally for poverty eradication. This article highlighted the fact that both the masters (the rich) and the servants (the poor) have the same make-up and Maker despite their positions and conditions in life.

The core of the matter is what John Calvin argued from his ecodomy framework, namely that, based on the allegiance to the same Maker as Lord of all who created both the masters and the servants alike, the rich and the masters should, on the one hand, moderate excess in their superiority, but on the other hand the servants (serfs) must submit to their masters.

Therefore, both should conduct themselves equitably among each other because of such creation right. It is on this basis (principle) that Paul left the condition of masters-slave to sort itself (cf. CO 51.798). It is such conscious decisions which can give us enough motive and basis to eradicate poverty as our missional call before our Maker also today.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, to triune God be all glory (1 Cor 10:31 & Col 3:17). Secondly, to Alvinah (my wife for her Pr 31 support), to Ms Blanch Carolus (academic support) and my children (Vhuhwavho, Mufulufheli, Wompfuna, Thamathama, Lupfumopfumo and Tshontswikisaho (family support).

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Authors' contributions

T.A.M. declared sole authorship of this research article.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human participants.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and are the product of professional research. It does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated institution, agency, or that of the publisher. The author is responsible for this article's findings, and content.

References

Arias, M., 1984, 'Mission and liberation: The jubilee - A paradigm for mission today', International Review of Mission 73(289), 33-48. [ Links ]

Augustine, 1960, The city of God: Books XIX-XXII, Triumph of the celestial city, 4th edn., B. Dombard & A. Kalb (eds.), French transl. G. Combès, Desclée de Brouwer, Paris. [ Links ]

Biéler, A., 2005, Calvin's economic and social thought, World Alliance of Reformed Churches, Geneva. [ Links ]

Bouwsma, W.J., 1988, John Calvin: A sixteenth century portrait, Oxford University Press, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Bouma-Prediger, S., 2001, For the beauty of the Earth, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Bouma-Prediger, S. & Brian Walsh, J., 2008, Beyond homelessness, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Brueggemann, W., 1977, The land: place as gift, promise, and challenge in biblical faith, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Busch, E., 2007, 'A general overview of the reception of Calvin's social and economic thought', in E. Dommen & D. Bratt (eds.), John Calvin rediscovered: The impact of his social and economic thought, pp. 67-75, Westminster John Knox, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Calvin, J., 1583, The sermons of John Calvin upon the fifth book of Moses called Deuteronomy, transl. A. Golding, Henry Middleton, London. [ Links ]

Calvin, J., 1847-1850, Commentary on the first book of Moses called Genesis, transl. J. King, 2 vols, Calvin Translation Society, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Calvin, J., 1852-1855, Commentaries on the four last books of Moses arranged in the form of a Harmony, transl. C.W. Bingham, 4 vols, Calvin Translation Society, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Calvin, J. 2000. Sermons on Genesis, chapters 1 to 20.4 (Supplementa Calviniana XI/1-2), M. Engammare (ed.), Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchener-Vluyn. [ Links ]

Calvin, J., 2006, Institutes of the Christian religion, J.T. McNeill (ed.), transl. F.L. Battles, Westminster Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Collins English Dictionary, 2012, Digital Edition HarperCollins, viewed 10 March 2023, from http://www.dictionary.com/browse/laissez-faire. [ Links ]

Conradie, E., 2011, Christianity and earth keeping: Resources in religion and theology 16, SUN Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Dabney, R.L., 1985, Systematic Theology, Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Dillard, R.B. & Longman, T. III, 1994, Christianity in crisis: The 21st century, H. Hanegraaff (ed.), Zondervan, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Erasmus, S., 2016, 'Rich man, poor man', Fin24, viewed 10 June 2023, from http://www.thinglink.com/scene/505528119466131458. [ Links ]

Freudenberg, M., 2009, 'Economic and social ethics in the work of John Calvin', in A.A. Boesak & L. Hansen (eds.), Globalisation: The politics of empire, justice and the life of faith, pp. 158-161, Sun Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Gamble, R.C., 1992, Calvin's thought on economic and social issues and the relationship of church and state, Garland Publishing, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Graham, W.F., 1971, The constructive revolutionary: John Calvin and his socio-economic impact, John Knox Press, Geneva. [ Links ]

Hall, D., 2010, Tributes to John Calvin: A celebration of his quincentenary, P&R Publishing, Phillipsburg, New Jersey. [ Links ]

Harris, M., 1996, Proclaim Jubilee, Westminster John Knox, Louisville, KY. [ Links ]

Hodges, J.M., 2010, Beauty in music: inspiration and excellence for Veritas Academy Fine Arts Symposium, Veritas Academy Press, Lancaster. [ Links ]

Lowery, R.H., 2000, Sabbath and Jubilee, Chalice Press, St. Louis, MO. [ Links ]

McKim (ed.), 1984, Calvin and the Bible, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, viewed 10 June 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606908.009 [ Links ]

Nyomi, S. (ed.), 2008, The legacy of John Calvin: Some actions for the church in the 21st century, The World Alliance of Reformed Churches, Geneva. [ Links ]

Preston, R.H., 1979, Religion and the persistence of capitalism, SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Selderhuis, H.J., 2009, The Calvin handbook, Eerdmans, Michigan. [ Links ]

Sider, R.J., 2005, Rich Christians in an age of hunger: Moving from affluence to generosity, Thomas Nelson, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Tidball, D., 2005, 'The message of Leviticus', Free to be holy, Inter-Varsity Press, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

Torrance, T.F., 1956, Kingdom and church, Essential Books, Phillipsburg, NJ. [ Links ]

Ver Eecke, W., 1996, The limits of both socialist and capitalist economies, Institute for Reformational Studies, PU for CHE, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Weinfeld, M., 1995, Social justice in ancient Israel and in the ancient Near East, Fortress, Minneapolis, MI. [ Links ]

Wenham, G.T., 1979, The book of Leviticus. New International Commentary of the Old Testament (NICOT), William B. Eerdmans Publishing co, Grand Rapids, Michigan. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Takalani Muswubi

muswubi@gmail.com

Received: 23 Apr. 2023

Accepted: 31 Aug. 2023

Published: 29 Nov. 2023