Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

In die Skriflig

On-line version ISSN 2305-0853

Print version ISSN 1018-6441

In Skriflig (Online) vol.55 n.1 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ids.v55i1.2645

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v55i1.2645

Church decline: A comparative investigation assessing more than numbers

Ignatius W. Ferreira; Wilbert Chipenyu

Department of Missiology, Faculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Studies on church growth and decline were done in different parts of the world. This article explores church decline that is continuing in the world's mainline Protestant churches and is also affecting the Reformed Churches in South Africa (RCSA). It is done from a missiological framework, and the description goes beyond numbers in establishing decline to focus more on the quality of believers. Membership quality is all that the church strives for in all believers, and failure to reach that goal leads to decline. The study utilised only primary sources to describe the decline realised in these churches; thus, no human subjects were involved. The various reports of the RCSA deputies for turn-around and church growth as well as the relevant literature, provided the data required for the present research. The numerical data explain the trends in church decline that is taking place in Protestant churches globally and locally which includes the RCSA. These findings are substantiated by the definitions of church decline and church growth as well as indications of church health highlighting 'what happens' to the church in a specific context. The explanation of key concepts and the Natural Church Development (NCD) benchmarks provided the lenses to evaluate the membership statistics of Protestant churches including the RCSA. Through the application of these key concepts and benchmarks, it became evident that the ongoing numerical reduction in membership, which began in 1994, is proof of church decline in the RCSA.

CONTRIBUTION: This article chose a 'missiological framework' referring to the Great Commission and the missio Dei in order to challenge a more 'static' (numbers only) and 'church survivalist' approach to the current 'church growth and decline' reality within the Western Church. In this way, the focus on'church health' rather than the dominant Practical Theological approach to 'church growth' will lead to new knowledge that will benefit and subsequently strengthen the current debate.

Keywords: church growth; church decline; church health; missiology; Protestant church; mainline Protestant churches; quantitative church growth; qualitative church growth; Reformed Churches in South Africa (RCSA).

Introduction

Based on the testimony running from the Old Testament through to the New Testament, God chose a specific people whom he tasked as his messengers in the world to take part in the missio Dei (Kaiser 2000:10, 22; Peters 1972:160). Israel was called in the Old Testament and the church in the New Testament as the agents making God present to the world. This makes the church responsible for reaching out to different nations and lead them to Christ (Mt 28:18-20). Jesus gave the 'marching orders' to the church with his command that believers must reach out with the Good News to all peoples. Three aspects in the Great Commission are worth noting:

-

Jesus has total authority in heaven and on earth to accomplish the missio Dei through the church in the world.

-

The church is sent to all peoples with the Gospel and to incorporate converts into God's kingdom family, which results in growth.

-

Christ promised to be with the church all the time while fulfilling the Great Commission.

These three aspects make church decline a missiological problem, as under usual circumstances growth should be realised instead. The Great Commission provides both the goal and emphasis of the church's outreach to the world. When the church participates in the Great Commission, disciples of Christ are made from all peoples on the face of the earth (Conn 1976:61-62; Cross 2014:93; Peters 1972:188; Shenk 1983:99). The missio Dei is constituted of two aspects that are revealed in Jesus' command to the church (Mt 28:18-20). Firstly, the kingdom family is meant to grow in quantity, as the world is led to Christ through the witnessing of the church. Secondly, the converted peoples should be fed with the Word to become disciples of Christ and also 'grow in quality'.

The purpose of this article was to describe the ongoing church decline in Protestant churches globally and locally. Further attention was paid to the decline occurring in the Western world, South Africa and, especially, in the Reformed Churches in South Africa (RCSA). Central to this article is the description of decline based on the missiological foundations of the church that is anchored in the quality of members or disciples of Christ (Mt 20:20). Membership's statistical reflection collaborates with their quality to determine what is going on in the church. In this regard, the study used research question 1 of Osmer (2008:4): 'What is going on?' This query, called 'priestly listening' by Osmer (2008:34), formed the basis for discussing the context of the present study: situations in Protestant churches globally and in the RCSA. This research question also provides the boundary to the study. Thus, only information was gathered that reflects the mentioned context of the study. The gathered information is presented in tables and the trends for the various contexts compared and discussed.

A further aim was using the definition of key concepts and the Natural Church Development (NCD) quality principles (Schwarz 1996) to validate the numerical data that are presented for the Protestant churches. The definition of church growth and decline in accordance with the NCD principles is used to explain the statistical trends of the Protestant church and thereby establishing whether there is indeed decline. The premise is that church decline and growth is not only measured by the quantity of members, but also their quality. The NCD does not make up the core of the present study, seeing that these guidelines are only used to describe the life of a biblically-oriented church.

Therefore, statistics and accompanying explanations are important to investigate the quality and quantity of members in congregations before concluding whether church growth and/or decline is taking place. Overall, scholars agree that aspects of church growth or decline are understood better through clear definitions of the two key concepts and by providing relevant figures (Chung 2014:35; Roxburgh & Boren 2009:118; Wagner 1998:22-23). Defining qualitative and quantitative growth provides better insight into whether the numerical trends among churches show growth or decline. The NCD principles and key concepts establish parameters that are used to establish whether there is church decline in Protestant churches globally and locally in the RCSA. The numerical data of churches are presented below.

The trends in Protestant churches across the world

Church decline in the world

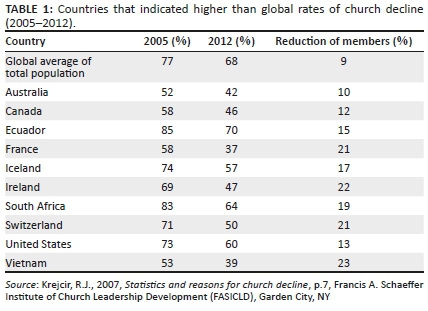

Research on membership trends shows an ongoing decline in membership within Protestant churches in different countries worldwide. The Western countries indicate the largest figures of membership decline in the world (Krejcir 2007:7). Table 1 presents the figures for church decline compared to the global average as well as the decline in South African Protestant churches.

Table 1 above indicates that the identified countries reported high rates of membership decline in various parts of the world. Such reduction numbers indicate that churches globally are having to deal with numerical decline. However, dealing with numerical decline is possible when the church first attend to membership spirituality. These high reduction figures are taken during a period of seven years (2005-2012). The Western countries comprise 77.7% of global reduction, while the other parts of the world, combined, indicate a reduction of 22.3%. South Africa is the only African country among the 10 with the highest decline rate, implying that it is at the top of the list of membership declines in Africa as a whole.

Church decline in the West

To show further membership decline rates in the West, Bendavid (2015:3) provides the following graphic illustration of the percentages of Christians in specific European countries. This graph is presented in Figure 1.

The graph above shows decreasing percentages of members who profess to be Christians in the European countries under investigation. Ireland indicated the highest Christians membership of 60% in 2002 which declined to 49% in 2012. This is a membership decrease of 11% over a period of 10 years. The rest of the countries indicated that less than 40% of their population were Christians in 2002, which, in most cases, implies a further percentage decrease during the period under study. Despite Italy's steady increase in Christian percentages over the 10 years, the highest percentage was 39%, which still indicates a low membership. Spain shows a decrease from 28% to 20%, and thereafter a slight increase to 25%. Nevertheless, this increase does not enhance its Christian membership. Regarding the percentages in these selected European countries, Bendavid (2015:3) concludes that, even though the churches did not close their doors, the pews were empty. In other words, the membership declines warranted closure of churches, but officials decided to continue with mostly empty pews.

Discussion of church decline in the West

The data from Table 1 and Figure 1 validates the findings by Meacham (2009:3) about a sharp decline from 1999 to 2009 in Protestant membership in the Western world with a subsequent rise in the number of people who consider themselves non-Christians. Seemingly, the commitment to Protestant Christianity was overridden by following a non-Christian way of life. In the same vein, figures of people in the West attesting to be atheist increased rapidly from 1 million to 3.6 million (Meacham 2009:3). This concurrency in the drop of Western Christian membership and the rise in professed atheists may lead to the deduction that members who left the Protestant churches affected the increasing growth rates of atheism in the West. The reason is that church decline result from members who are spiritually immature (Mckee 2003:22), and these can be part of the atheist cohort by virtue of their spirituality.

Krejcir (2007:1) notes that American Protestant churches declined by 5 million members (i.e. 9.5%) from 1990 to 2000. He adds that half the churches did not add new members for two years preceding 2007. The result was the continuous decline of membership. For example, in 1995, the mentioned American churches had lost between one fifth and one third of its total membership (Johnson 2004:13). From 1980 to 1989 there was an average of 10% decline in membership and it increased to 12% from 1990 to 1999 (Krejcir 2007:1). The scholar adds that, although the average was found to be 12% from 1990 to 1999, certain congregations indicated a membership decline of up to 40%.

A similar scenario of ongoing decline in American Protestant churches is also found in the European countries as shown in Figure 1 above. Bendavid (2015:4, 7) argues that the high decline rate in Europe led to the closure of certain congregations. The scholar points out that numerous of these former church buildings in Europe currently have been turned into galleries, clothes shops, bars (pubs). Thus, the 'white elephant' church buildings were sold off for other uses. Mabry-Nauta (2015:22) reports that, on average, nine churches close their doors daily in America due to the high decline rates as shown on in Table 1. Similarly, UK church attendance was halved and in Germany, 50% of the population attest that they do not believe in God. Van der Walt (2009:253) points out that, in Europe, 35 000 church members exit church life every week, and in England 1500 left the church during the same period. The decline in membership in Protestant churches globally indicates a church that is not fulfilling God's purpose in church growth (Nel & Schoeman 2015:22). Growth is not possible in a church that does not have full expression of its intended purpose in its community.

Church decline in South Africa

Christianity in South Africa has been on the increase since the missionary era. South Africa was known as a Christian country whose governance was aligned to biblical principles (Elphick & Davenport 1997:277). Being a Christian country meant that Christians had an advantage in national matters. Such a context may have influenced 'outsiders' to become part of the Christian family. The motives would not be their love for Christ, but to pursue individual interests. Those who became church members for personal gain were in the church and not of the church. Notwithstanding the motivation of adherents, the membership numbers were on the increase in South Africa.

This trend for Protestant churches only changed since the 1980's when it shifted from growth to decline, which is ongoing (Goodhew 2000:358). As is the case with the West, South African Protestant churches are continuously losing members, which leads to the closure of certain congregations (Elphick & Davenport 1997:397). Goodhew (2000:355-366) argues that decline in mainline Protestant churches in South Africa is affecting all groups of people in varying degrees. Nevertheless, it seems that black people record the highest percentage of membership decline. Hendriks and Erasmus (2001:39) point out that the black people constituted 54.4% of the total membership for the Protestant churches before 1991. However, the black population in these Protestant churches was reduced by 44%: from 54.4% to only 10.4% active members (Hendriks & Erasmus 2001:39). Such a decrease affects the quantity of membership in the different Protestant denominations. Table 1 indicates that the South African membership decline rate raised above the global average. Church membership is positively or negatively affected by the context in which the church is found. Nel and Schoeman (2015:98-99) point out that the politics, education, health, economy, social and cultural aspects affect church membership in South Africa.

The membership decrease is also occurring in the RCSA. In 1930 the RCSA had a Christian membership of 48 806 which increased to 116 053 in 1987 (Gereformeerde Kerke van Suid Africa 2018:1). The synod of 1994 noticed membership decline in the RCSA (Deputies for turn-around and church growth 2015:428-432). In 1994, the RCSA membership figures had dropped by 2993 to 113 060 members, which implies a decline of 2.6%. In this regard, Hendriks (1995:41) found that during this period, membership decline in South Africa increased by 14.4% to 17%, highlighting why South Africa was the only country singled out from Africa with the highest Christian decline rates as was indicated in Table 1.

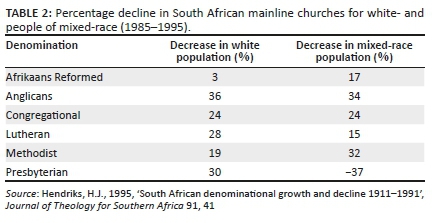

Table 2 provides statistics for decline in membership of white people and people of mixed-race in different Protestant churches alongside their black counterparts. The reduction in white and mixed-race membership indicates that decline affects congregations across races. The liberal democracy observed by Van Zyl (2011:337) may have affected church quality for all races, which is influencing the quantity of members from the various churches.

Table 2 shows that both the mixed-race and white congregations experience membership reduction in varied percentages.

Goodhew (2000:355) points out that, although all denominations in South Africa are experiencing decline, the Protestant churches are affected the most. He adds that the different Reformed church denominations are showing the highest percentage of decline in membership. These denominations plunged from 34% of the total Christians in 1911 to 15% in 1996: which explains their high decline rate of 19% (Goodhew 2000:366). In the same vein, a survey, carried out by Khaya (2010:1), shows that Reformed church denominations were also heading the list of membership reduction in South Africa. The study established that these denominations recorded a decrease of 15% from 1996 to 2001.

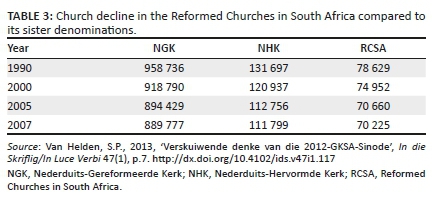

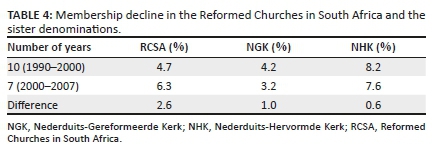

Table 3 below indicates the decline rates of the RCSA and its sister denominations, namely the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa (Nederduits-Gereformeerde Kerk [NGK]) and Dutch Reformed Churches in Africa (Nederduits-Hervormde Kerk [NHK]) from 1990 to 2007. The figures for the NGK indicate that from 1990 to 2000 there was a membership reduction of 39 976 and in the following seven years (2000-2007) the reduction was 29 013. The reduction in the same period for the NHK amounted 10 760 and 9138 respectively. The RCSA indicated a membership reduction of 3677 from 1990 to 2000 and 4727 from 2000 to 2007. All three denominations show a growing membership reduction if the decline figures are compared for the period of 10 and 7 years respectively.

Table 4 indicates that the RCSA has a higher rate of decline for 7 years than for 10 years. This implies a 2.6% increase in membership declines in 7 years compared to 10 years. The indication is that the rate of membership declines in static churches increase with time. Thus, figures are showing a continuous rise in membership decline in the RCSA. On the other hand, both the NGK and NHK had a lower membership decline for 7 years than for 10 years. They both indicate lower percentages of membership reduction. The difference in membership reduction over the 10 and 7 years are as follows: NGK 1% and NHK 0.6%.

Table 5 provides a more detailed reflection of the membership reduction in the RCSA. The decline is provided in intervals of varying years, namely 10, two, five and one. The figures indicate that the RCSA had a membership reduction of 16.72% from 1990 to 2000. This gives an annual average reduction of 1.7%. The decline from 2000 to 2002 was 1.7%, which gives an annual average of 0.9%. These figures indicate a reduced percentage in membership declines. However, the years 2002 to 2007 recorded an average of 4.8%, which translates to an annual average of 1%. The percentage of membership reductions began growing again. Seemingly, the increase in membership reduction occurs annually, which is evidenced by a further annual reduction of 2% from 2007 to 2008.

In light of the previous exposition, Table 6 presents the figures for the RCSA membership from 2007 to 2019.

Table 6 indicates both membership increase and reduction. The years 2007 and 2008 were added to this table in order to indicate an acute shift from membership declines in these 2 years to a marked rise in membership numbers in 2009. This increase in membership only occurred from 2009 to 2012 and the decline trend continued again from 2013 to 2019. Although the membership quantity reflects an increase from 2009 to 2012, the Administrative Bureau (Gereformeerde Kerke van Suid Africa 2018:1) stated that the rise in membership numbers was due to the unification of Synod Midlands classis Capricorn and Potchefstroom. In addition to the unification leading to the increase in membership figures, the Administrative Bureau reports that, over the four years (2009-2012), certain black churches provided inaccurate information of membership. This error was realised afterwards and was corrected to reflect the actual membership. Nevertheless, there was neither numerical growth as such in this membership migration, nor was there evidence of spiritual growth. Numerical growth is accounted for in two ways as prescribed in the Bible (Gn 12:2-3, 17:10; Mt 28:19-20):

-

Conversion of peoples from far and wide with the Gospel of truth (Mt 28:19-20) which is also regarded as a blessing to all peoples (Gn 12:3c).

-

When believers' children commit themselves to the Lord (Gn 12:2; 17:10).

This is discrediting the migration or transfer of members from one congregation or denomination to the other. In this regard, there is no evidence of new converts brought into the RCSA during the above-mentioned years except through unification, which involved those from the two sections who were RCSA members already. From the information provided by the Administrative Bureau (Gereformeerde Kerke van Suid-Afrika 2018:1), it was evident that the rise in membership numbers was not growth as such, as no new converts were identified.

The statistics from Table 6 shows membership reduction from the unified Synod Midlands classis Capricorn and the RCSA Potchefstroom from 2013 to 2019. This finding indicates that church decline continued in the RCSA even though the figures increased rapidly from 2009 to 2012 after the unification process. The figures show a membership decline of the unified church in both the members confessing their faith and those who were baptised. The reduction in the baptised and confessing members affects both the present and future of the RCSA. The reformed tradition upholds the sacrament of baptism. The baptised members are covenant children who are expected to be full RCSA members when they are adults. Reduction in baptised membership indicates reduced membership in the following years. The increase in baptised people points towards growth, whereas a decrease shows decline. The reduction in baptised members in 1994 seemingly affected the figures of those confessing their faith in the following years.

From 2013 to 2019, the figures of people confessing their faith decreased by 14.2%, which amounts to an annual average decrease of 2%. The baptised members decreased by 24% in the same period; thus, an annual average decrease of 3.4%. The grand total decrease of the confessing and baptised members was reduced by 48.2%, which is an average decrease of 5.4% annually. The decrease of 48% over these seven years nearly halved the RCSA membership in the stated period. However, the figures show a slight decrease in annual membership reduction from May 2018 to May 2019 when numbers of confessing congregants decreased by 2.9% and those of the baptised members to 0.7%. Thus, the grand total decrease was 3.6% during that period. This amounts to 1.8% difference in annual membership reduction from 2013 to 2019 as well as between 2018 and 2019. Although this reduction is lower than average for the seven years (2013 to 2019), it is higher than the previous years (2007 to 2008), which entailed 2.5% membership decline.

Although membership reduction seemingly indicates decline in the Protestant churches, more information should be gathered. Thus, the collected data helps to describe whether the decline in membership can be considered as church decline or not. The statistical trend indicates membership decline against God's purpose in calling for church growth (Gn 12:2-3; Mt 28:19-20; Nel & Schoeman 2015:20). If all other factors that might affect numerical decline are under control, these statistics indicate real church decline. Thus, real church decline indicates both qualitative and quantitative decline of membership. Therefore, it stands to reason that church decline and church growth goes beyond the numerical figures to include the quality of Christians.

Definitions of key concepts

Based on the conclusion above, clear delimitations are necessary to help understand the context of the research. The definition of key concepts sheds light on the relationship between the quantity and, especially, quality aspects, which enhances all believers to be missional. It is a missiological concern that believers be an expression of God in their varied communities (Nel & Schoeman 2015:88) to transform them to be Christians. Relevant Scripture verses emphasise that the followers of Jesus Christ should both increase in number and exhibit the Christ-like character in who they are, what they say, and what they do to become his disciples (Mt 28:19-20; Ac 2:42). These Scriptures indicate the increase in numbers and in the knowledge of Christ. Therefore, it is untenable to substantiate church growth or decline only referring to membership numbers without considering the quality of the members comprising the congregation (Booth, Colombo & Williams 2003:328). Without clear and articulate definitions describing the correlation between member's quantity (numerical) and quality (spiritual), research would fail to describe the ongoing situation in the Protestant churches accurately. As explained, church decline or growth reaches beyond the membership numbers.

Church growth

Wagner (1998:75) defines church growth as a 'science which investigates the planting, multiplication and health of Christian churches, in response to the Great Commission'. Wagner concurs with McGavran (1990) on the importance of membership increase in church growth. He goes further to point out that the converted members should also live as healthy Christians. His argument is based on the Great Commission (Mt 28:19-20) where the two dimensions of church growth, quantity and quality, are emphasised.

Numerical growth is an important biblical theme as demonstrated throughout the Scriptures. (e.g. Gn 1:28; 12:3; Is 11:9; Mt 18-20; Dn 2:34-35). All these verses describe God's eternal plan that the whole world should come to know him as the King of kings and Lord of lords. The inclusion of the whole world increases the numerical figures of the church. Nevertheless, the mere increase in numbers cannot be used as an exclusive measure of church growth. As the body of Christ, the church is expected to grow in both dimensions to be a healthy institution. There can be no quantity without quality. Numerical growth without quality is deformed, which is dangerous to the body of Christ. The reason is that numerous Christians in such a church are spiritually undernourished and unhealthy. Thus, they hampered from doing what is expected from the church of Christ (Costas 1983:98). A mere increased numbers of members in a church who have not experienced an intimate relationship with Christ, results in superficial growth. The deficiency lies in members who do not reflect Christ's teaching about his church according to Matthew 28:19-20, namely being his disciples and imitating him.

Based on the discussion above, only spiritually mature members can fulfil the mandate of the church. All church members should be active parts of the body of Christ, reflecting his light into the world through their daily lives as suggested in the biblical testimony (Mt 5:13a, 14; Pr 4:18; Rm 2:19; Eph 5:8; Phlp 2:15).

In Matthew 28:19-20, Jesus emphasised the need for spiritual growth in all the members who are converted. Two out of three verbs πορευθέντες [going] and βαπτίζοντες [baptising] in Matthew 28:19 are participles. Only μαθητεύσατε [making] disciples is the main action verb pointing to the importance of the spiritual growth of converted members. Furthermore, Matthew 28:20 focuses on teaching the converts what Christ had taught. Such a command also aims at the spiritual growth of all converted members. In Acts 2:41-42, Luke indicates clearly that those who were converted and added to the Early Church were devoted to the apostolic teaching. The latter teaching transformed the converted into disciples of Jesus and thereby accomplishing both numerical and spiritual growth of the church. The quality of members is therefore central in determining the state of the church. Thus, quantitative decline is a response to the qualitative decline of members who are not missional to continue in the church or influence their communities to Christianity. The correlation of the two dimensions that comprise true biblical church growth is derived from Chaney and Lewis (1977:13) as explicated in the three postulates to follow:

Qualitative growth should produce quantitative growth unless its quality is suspect: Quality that does not lead to quantity is counterfeit and not genuine. Counterfeit quality occurs when members profess, but their lives do not testify of this claim. According to Luke 6:46 and Matthew 7:22-23, Jesus explains that he does not engage in a relationship with followers who lack quality. Without a relationship with Christ, church members are unable to transform other people, as they are not renewed themselves. They cannot give others what they do not have themselves.

Quantitative growth makes qualitative growth possible, as many people are converted (quantity) and then discipled, and thereby producing quality: Qualitative growth can only take place after quantitative growth. The reason is that the church can only disciple the converted people in their churches. Therefore, introducing new converts to churches provides the opportunity to develop quality in these members. Quantitative growth is the entrance-point to church growth which is destined to generate qualitative growth.

Quantitative growth that is not aimed at qualitative growth is unsustainable: Quantitative growth needs its qualitative content to increase if the growth is to be sustained. During latter growth only quality members remain in the church where more members can be led to Christ. This latter growth process naturally influences quantity.

Church decline

Reduction in church membership is often used to justify church decline, because such a decrease is not considered a trend in the church of Jesus Christ. Several scholars point out that a church is expected to grow and when there is reduction in membership, decline can be presumed (Chung 2014; Goodhew 2000:353; Hitchens 2000). Although the mentioned scholars' argument is partially correct, it cannot be used as the cutting edge to define church decline. Membership reduction is a sign that processes occur that is not typical of being the church. Further investigation is necessary to determine the reasons for membership reduction. A precise definition of church decline should focus on the relationship between the quality and quantity of members as growth takes place (Mt 28:19-20).

A biblical standard of the church is realised when it functions as a united body of Christ. This is characterised by brotherly and sisterly love, the unity and diversity of various members as enacted by the Apostolic church (Ac 2:42, 44). Four characteristics in the Apostolic church makes it grow in terms of the two dimensions of quantity and quality: κοινωνίᾳ [fellowship], προσκαρτεροῦντε τῇς διδαχῇ [devoting themselves to apostles' teaching], κλάσει τοῦ ἄρτου [breaking of bread], and προσευχαῖς [prayer]. These church activities result in quality Christians who can transform their communities proclaiming the gospel of Christ. Membership service in the church leads to growth.

The life of the church, as mentioned above, fulfils the unity in the body which enables every member to serve; thus, growth is realised. Both unity and diversity are important for members to serve effectively in the body. When a number or all these attributes of a biblical church are absent, decline occurs. The case may be that a spiritually filled church loses members due to other reasons such as relocation to other areas. In such instances, a church cannot be considered to be in decline, because the few remaining members possess the required attributes. Real church decline occurs when quality is absent among members or when both quality and quantity have decreased.

After examining the two dimensions closely, it can be concluded that, in most cases, spiritual decline precedes the numerical one. The reason is that a church with spiritually immature leaders and members conform to the standards of the Word, which are in opposition to the will of God for the church (Rm 12:2a; 1 Pt 1:14; 4:2). Members who have deviated from the guidelines, provided in the verses above can be considered in spiritual decline. As a result, exiting members leave the church without new members being incorporated.

Members whose spirituality has declined, are not able to influence numerical growth through biological numbers, transfer and conversion; instead, they leave the church of their own accord (Goppelt 1970:34; Reeder & Swavely 2008:64; Stoll & Petersen 2008:252). The argument is that, as the members are unable to impact any one of the three dimensions of growth, the church is failing its mandate and the result is church decline. If a church deviates from God's purpose for its reason to exist, it ceases to influence its community. As a result, the members' holiness, love and communion deteriorates and eventually become non-existent (Costas 1983:100). In other words, a church that has deteriorated spiritually, does not participate in the missional duties of a healthy church.

A deteriorating church does not attract new people or influence their family members to follow Christ; thus, no numerical growth occurs. Eventually, such a church becomes unhealthy (Jenson & Stevens 1981:17-19) - neither leading other people to Christ, nor retaining its own members. Such a church becomes irrelevant to both the community and the members themselves who would leave it at a certain stage. Membership continues to decrease, because no new converts are introduced into the church to replace those who had left (Goppelt 1970:34; Reeder & Swavely 2008:64). A spiritually declining church affect both the mature Christians and those who have conformed to the standards of this world. The mature Christians leave the church, because they cannot see themselves being part of a deteriorating church culture, while the other group leaves, because they have lost their love for Christ.

A stagnant church reflects the members' spiritual coldness, which cannot lead to growth. McIntosh (2009:71) provides the following characteristics of a church in spiritual decline that manifests in membership reduction or stagnation:

-

Members are without the knowledge of salvation by grace. Lack of adequate knowledge about this vital doctrine, inevitably leads to spiritual decline.

-

Members' character is not aligned with Christian ethics.

-

Converts are led to the church without true repentance, and their lives remain unchanged.

Therefore, a stagnant church only moves in the direction of decline when members die or leave the church for one reason or the other. A church that does not participate actively in its community by reflecting Jesus' character, has ceased to practise its faith. This is an indicator of declined spiritually, which would also lead to numerical decline (Costas 1983:104). Becoming a stagnant church is the first turning point from growth to decline.

Healthy church growth

Numerous scholars point out that meaningful church growth focuses on church health in which all converted members are led to become disciples of Jesus, (McKee 2003:17; Reeder & Swavely 2008:31; Roxburgh & Romanuk 2011:118; Stetzer & Putman 2006:25). A healthy church is able to lead as many people as possible to Christ and endeavour to make them disciples of Jesus as in the case of members who are committed already. Such transformation is reached when converted members adhere to the biblical principles in their daily lives, being led by the Spirit of God. The members' desire would be to glorify God in all aspects of life as articulated by Paul in his letters (e.g. I Cor 10:31; Col 3:17). Based on the Reformer, Calvin's view, Christ is testified as King in all areas of life and should be revered in these spheres. According to this belief, Christ rules in the members' congregations, families, workplaces and multiple other areas of their lives. Having an intimate relationship with Christ is the only channel that allows his followers to function effectively. Applied to a congregation, such relationship amounts to church health. Church health thus entails the growth of its members' quantity as well as quality. Therefore, a church that indicates no growth in these two dimensions can be considered as dead. The reason is clear: as a body of Christ, a church must grow, unless it is diseased on a spiritual level (Jenson & Stevens 1981:19). It is therefore best to measure a particular church's effectiveness in terms of its spiritual-health status rather than membership numbers and ostensive size of the congregation (Roxburgh & Romanuk 2011:118; White & Ford 2003:39). Church growth, based on biblical guidelines, means continually introducing new members and teaching them to obey Christ's teaching. A healthy church thus follows the Jesus model of church growth according to which converted people should all be made his disciples (Mt 28:19-20; Ac 1:8). This model was used successfully by the apostles in planting healthy churches.

A healthy, growing church is a missional one whose members present themselves in the communities where they live, applying the love of Christ to all people (Costas 1983:102). Such a church aims to spread the gospel of Christ globally, leading as many people as possible to Christ. Missional congregants are not confined to the four walls of their church building, but are launched beyond the congregation. Such a church implements processes to ensure the converted members receive adequate discipleship training and to help them mature spiritually. The aim is that all members who are affiliated to this congregation become true disciples of Jesus striving to glorify God in the various spheres of life (Col 3:17; I Cor 10:31).

Two important aspects regarding a healthy church can be highlighted:

-

It incorporates quality members who will remain in the church.

-

These quality Christians participate actively in the Great Commission where they lead others to become disciples like them.

Insight gained from the definition of terms

The quantitative and qualitative growth of members are the two determinant factors that indicate church growth or decline. These dimensions are important to shed light on 'what is happening' in the church (Osmer 2008:4). The quality of members affects the quantity in the direction of growth and/or decline. If the members are spiritually mature (quality), their quantity increases. If the quality of the members is weak (spiritually immature), the quantity is reduced. The reason is clear: The members cannot influence other people to become Christians and even the spiritually weak members would not remain in the church. The quality dimension is important for church health. In this regard, quality members are the light and salt of the world (Mt 5:13-14). Their daily lives are characterised by the love of Christ that attracts other people to their congregations. Such members' deeds witness to Christ in all aspects of life (Conn 1976:62).

Applicable benchmarks can be established for biblically-based quality in congregations implementing Schwarz's (1996:19) NCD quality principles. These quality principles are generic and can lead to the spiritual growth of the concerned members in congregations. The eight NCD quality principles are discussed below:

-

Empowering leadership: The minister of religion concentrates on developing the ministry of the congregation by identifying, developing and mentoring the leadership 'to become all that God wants them to be'. (Schwarz 1996:22). The empowered leadership can influence quality in ministries of their various congregations.

-

Gifted-oriented ministry: The empowered leadership helps the congregants discover their gifts, develop them. Thus, the believers are enabled to serve actively in the body and thereby building the quality of members, which is characterised by commitment of faith being missional.

-

Passionate spirituality: Quality believers' lives are committed to 'practice their faith with joy and enthusiasm' (Schwarz 1996:26). A church that is committed and enthusiastic about its faith, fulfils the Great Commandment - loving God totally and neighbour unconditionally (Matt 2236-2240). For the concerned believers, their wholehearted devotion to God and others compel them to be Christ-like.

-

Functional structures: The structures of the church tend to promote rather than inhibit active participation of congregation members. The more the members are motivated to serve in the congregation, the larger the number of people introduced into the church and who are discipled.

-

Inspiring worship: Believers are inspired by true worship that let them gaze at the face of the Lord: engage with the Word, prayers, music in such a way that congregants experience the presence and power of the Holy Spirit. Regarding such worship, Schwarz (1996:31) argues that, when 'worship is inspiring, it draws people to the services "all by itself"'.

-

Holistic small groups: The membership's cohesion deepens their love, which is the essence of church health. New members are introduced and discipled more readily in small groups than at congregation level.

-

Need-oriented evangelism: The focus of this principle is to develop bridges that help share the gospel by meeting the need felt by people to be evangelised. The developed relationship between the church members and the target population creates an interest in non-believers to listen to the gospel, which is the Holy Spirit's instrument for conversion.

-

Loving relationships: Members' commitment to others connects the Great Commission and the Great Commandment. Full commitment to others and to God lead the members concerned to introduce other people to the church and disciple them.

Therefore, the absence of, or minimising the NCD principles, impacts the quality dimension negatively which also affect quantity. Schwarz (1996) argues that these NCD principles are the basis for church growth without which the church declines. It falls outside the scope of the present study to research particular church activities in order to determine whether Schwarz's NCD principles are realised. Nevertheless, the trends of membership seem to point at a lack of the quality dimension in the church.

Conclusion

Most studies on church growth and decline attribute membership decline (numerically) to church decline. The present study pointed out that actual church growth and decline goes beyond membership numbers. The starting point in describing 'what is going on' in Protestant churches globally and the RCSA was by clarifying the key concepts: church growth, church decline and healthy church growth. Such clarification and the NCD quality principles helped to give meaning to the membership statistics, which require external criteria. Schwarz's findings showed that the NCD quality principles for church health work similarly in various contexts. Thus, it can be concluded the absence of NCD quality principles may result in a spiritually immature congregation (compromised quality) that leads to decline in membership (quantity).

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for carrying out research.

Funding information

The research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agence of the authors.

References

Administration Bureau, 2019, Almanak 2019: Inligting van die Gereformeerde Kerke in Suid Afrika, Administratiewe Buro, Potchefstroom [ Links ]

Bendavid, N., 2015, 'Europe's empty churches go on sale', The Wall Street Journal, 05 January, pp. 1-8. [ Links ]

Booth, W.C., Colombo, G.G. & Williams, J.M., 2003, The craft of research, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Chaney, C.L. & Lewis, R.S., 1977, Design for church growth, Broadman Press, Nashiville, TN. [ Links ]

Chung, B.J., 2014, 'A reflection on the growth and decline of the Korean Protestant Church', International Review of Mission 103(2), 319-333. https://doi.org/10.1111/irom.12066 [ Links ]

Conn, H.M., 1976, Theological perspectives of church growth, The Deddens Foundations, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Cross, E.N., 2014, Are you a Christian or a disciple! Rediscovering and renewing New Testament discipleship, Xulon Press, Maitland, FL. [ Links ]

Costas, O.E., 1983, A wholistic concept of church growth: Exploring church growth, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Elphick, R. & Davenport, T.R.H., 1997, Christianity in South Africa: Political, social, and cultural history, David Philip, Claremont. [ Links ]

Gereformeerde Kerke van Suid Africa (GKSA), 2018, Handelinge van die vierde Algemene Sinode te Potchefstroom op 9 Januarie 2015 en volgende dae, Potchefstroom, besigtig op 14 Oktober 2019, vanaf http://www.gksa.org.za/pdf2018/GKSA%20HANDELINGE%202018.pdf. [ Links ]

Goodhew, D., 2000, 'Growth and decline in South Africa's churches', Journal of Religion in Africa 30(3), 344-369. https://doi.org/10.1163/157006600X00564 [ Links ]

Goppelt, L., 1970, Apostolic and post-Apostolic times, transl. R. Guelich, Black, London. [ Links ]

Hendriks, H.J., 1995, 'South African denominational growth and decline 1911-1991', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 91, 35-58. [ Links ]

Hendriks, H.J. & Erasmus, J.C., 2001, 'Interpreting the new religious landscape in post-apartheid South Africa', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 109, 41-65. [ Links ]

Hitchens, P., 2000, The abolition of Britain: The British cultural revolution from Lady Chatterley to Tony Blair, Quartet Books, London. [ Links ]

Jenson, R. & Stevens, J., 1981, Dynamics of church growth, Baker, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Johnson, R.W., 2004, 'Mission in the kingdom-oriented church', Review & Expositor 101(3), 473-495. https://doi.org/10.1177/003463730410100308 [ Links ]

Kaiser, W.C., 2000, Mission in the Old Testament: Israel as the light to the nations, Baker, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Khaya, K., 2010, Church growth-shrinkage, blog post, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Krejcir, R.J., 2007, Statistics and reasons for church decline, Francis A. Schaeffer Institute of Church Leadership Development (FASICLD), Garden City, NY. [ Links ]

Mabry-Nauta, A., 2015, 'The last Sunday', Christian Century 132(1), 22. [ Links ]

McGavran, D.A., 1990, Understanding church growth, 3rd edn., Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

McKee, S.B., 2003, 'The relationship between church health and church growth in the Evangelical Presbyterian Church', PhD thesis, Asbury Theological Seminary, Wilmore, KY [ Links ]

McIntosh, G.L., 2009, Taking your church to the next leve: What got you here won't get you there, Baker Books, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Meacham, J., 2009, 'The End of Christian America', Newsweek Magazine, 03 April, pp. 9-13. [ Links ]

Nel, M. & Schoeman, W.J., 2015, 'Empirical research and congregation analysis: Some methodological guidelines for the South African context', Acta Theologica 22(2), 85-102. https://doi.org/10.4314/actat.v21i1.7S [ Links ]

Osmer, R.R., 2008, Practical theology: An introduction, Wm. B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Peters, G.W., 1972, A biblical theology of missions, Moody Press, Chicago, MI. [ Links ]

Reeder, H.L. & Swavely, D., 2008, From embers to a flame: How God can revitalize your church, P&R Publications, Phillisburg, NJ. [ Links ]

Roxburgh, A. & Romanuk, F., 2011, The missional leader: Equipping your church to reach a changing world, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. [ Links ]

Roxburgh, A.J. & Boren, M.S., 2009, Introducing the Missional Church what it is, why it matters, how to become one, Baker Books, Grand Rapids, MI. (Allelon Missional Series). [ Links ]

Schwarz, C., 1996, Natural church development: A guide to eight essential qualities of healthy churches, Churchsmart Resources, Carol Stream, IL. [ Links ]

Shenk, W.R., 1983, Write the vision, Trinity Press International, Valley Forge, PA. [ Links ]

Stetzer, E. & Putman, D., 2006, Breaking the missional code: Your church can become a missionary in your community, B&H, Nashville, TN. [ Links ]

Stoll, L.C. & Petersen, L.R., 2008, 'Church growth and decline: A test of the market-based approach', Review of Religious Research 49(3), 251-268. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, J., 2009, 'Spirituality: The new religion of our time'?, In die Skriflig 43(2), 251-269. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v43i2.223 [ Links ]

Van Helden, S.P., 2013, 'Verskuiwende denke van die 2012-GKSA-Sinode', In die Skriflig/In Luce Verbi 47(1), Art. #117, 16 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ids.v47i1.117. [ Links ]

Van Zyl, M., 2011, 'Is same sex marriages unAfrican'? Same sex relationships and belonging in post-apartheid South Africa', Journal of Social Issues 67(2), 335-357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01701.x [ Links ]

Wagner, C.P., 1998, Your church can grow, Wipf & Stock, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

White, J.E. & Ford, L., 2003, Rethinking the church: A challenge to creative redesign in an age of transition, Baker Books, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ignatius Ferreira

naas.ferreira@nwu.ac.za

Received: 29 May 2020

Accepted: 29 Oct. 2020

Published: 18 Jan. 2021