Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

In die Skriflig

versão On-line ISSN 2305-0853

versão impressa ISSN 1018-6441

In Skriflig (Online) vol.54 no.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ids.v54i1.2586

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The angry and aggressive patient in clinical pastoral care: Towards a spiritual and hermeneutical approach within the interplay between hoping and dread

Daniël J. Louw

Department of Practical Theology, Faculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Aggressive behaviour is quite common to ailments and diseases that imply impairment and has an impact on mobility, communication and logical expression of frustration and disappointment. Within a clinical environment and medical setting, anger and aggressive behaviour impacts on the quality of caregiving and nursing. The phenomenon of anger, as related to the existential realm of anxiety and dread, is researched in order to detect its impact on coping mechanisms and human well-being. For example, what is the possible constructive value of anger in processes of healing and wholeness? Within the dilemma of bottling-up or uncontrolled catharsis, the moral dimension of anger is addressed. Within a pastoral approach to human wholeness, the spiritual and religious dimension of anger is explored. In this regard, the article probes into the realm of God-images. A praxis approach is proposed wherein a diagrammatic depiction of the interplay between hoping and the expression of anger is developed. It is believed that such a portrayal will contribute to a hermeneutics of hope care. To start 'seeing the bigger picture', is decisive for an understanding of pastoral caregiving as a theological endeavour.

Keywords: phenomenon of anger; aggressive patient; hope care; mercy of God; catharsis; pastoral diagnosis.

Introduction and problem identification

With clinical pastoral care is meant treatment and care within a specialised caring environment such as hospitals, frail care units, home-based care facilities and specialised sections attending to patients in the acute stage of aging who suffer from dementia and other physical impairments. In a clinical environment, a team approach is followed wherein different disciplines work together in order to foster human wholeness and general well-being. The team is guided by professionals in medical care, nursing, para-medical services, sociology, psychology and pastoral caregiving.

In clinical care, patients often present aggressive behaviour so that they are described as 'difficult' patients. It is often experienced that patients suffering from dementia, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease reveal strong levels of severe frustration and resistance to basic care.

Dementia refers to a progressive and irreversible deterioration of the cognitive-functional capacities of aging people's mental ability. Increasing confusion, memory loss, communication difficulties and outbursts of frustration are hallmarks of this condition caused by such progressive neurological disorders as Alzheimer's disease (Ryan, Martin & Bearman 2005:44). Hayes (2003:46) mentions the fact that the dementia sufferer is labelled as abnormal, deficient and categorised as separate from 'us' due to mood swings such as experiences of dread and suppressed anger. Such a process of stigmatisation easily ends up with learned helplessness and incompetence. Behaviours such as dozing, wandering, irritation or agitation may be read as signs that the person is no longer capable of social, spiritual and religious participation.

Mood swings that oscillates between helplessness, hopelessness and uncontrolled outbursts of severe frustration can be identified in cases of people suffering from HIV and AIDS (Van Dyk 2008:268). HIV-positive people are exposed to periods of severe disorientation. They present resistance behaviour and are prone to aggressive behaviour. They become angry with themselves and their environment.

Patients suffering from a heart attack often suffer from dread, morbidity and unarticulated anger (Louw 2008:329). After a myocardial infarction, as a result of high-risk factor (Weich 1982:23), patients may be subjected to extreme uncertainty, which may develop into anguish as a result of denial and unexpressed anger. Hahn (1971:167) mentions that these patients are in conflict with their new condition and are often most aggressive towards the doctors, caretakers and nearby family members.

Aggression surfaces in the semi- and acute phase of rational deterioration, physical weakness and psychic regression. Due to helplessness and hopelessness, despair and the experience of a narrowing future vision, a spiritual numbness and inner anxiety set in which lead to severe distress. Inner resistance without appropriate outlet and opportunities for expression lead to outburst of anger and attempts to inflict pain to caring staff, nurses, doctors and caregivers. Personnel easily feel abused and insulted, and eventually start to withdraw from the patient. Detachment sets in which causes even higher levels of aggression and anger. The downwards spiral of deterioration and regression takes over.

When anger sets in, the caring environment is immediately affected. Due to helplessness and an experience of professional limitation, nursing staff often respond with confusion, withdrawal or different levels of anger, or even aggressive behaviour. In order to defend themselves from physical attacks or insulting remarks, they start to distance themselves from the patient. The question sets in: How should caregivers and family members respond to aggressive reactions and patients resisting any form of treatment and assistance?

Presupposition

The presupposition of this article is that, without a kind of hermeneutical tool and diagnostic framework probing into the networking background of aggressive behaviour, confusion sets in and the effectivity of both the caregiver's response, as well as the patient's spiritual capacity for healing are severely hampered. In fact, the process of internalisation of severe ailments is channelled to the level of disintegration and possible destructive behaviour. Without a clear and proper paradigmatic framework for interpreting the possible destructive impact of aggression on processes of healing and a spirituality of wholeness, a caregiver's capacity and ability to deal with different levels of aggressive behaviour could be reduced to merely the level of the affective. However, if aggression and anger could be related to basic functions of being and an indication of a patient's struggle to come to grips with the impact of an ailment on general human health and well-being on the spiritual quest for meaning and hope, this kind of insight contributes to a more objective stance and appropriate response. The latter implies a view on anger and aggression that could be incorporated in what one could call the spirituality of human wholeness.

Hall, Hughes and Handzo (2016:3) refer to the fact that spirituality plays a fundamental role in processes of healing. 'Although spiritual and religious expression can be highly idiosyncratic and diverse, it remains relevant in the pursuit of providing the best possible health care.' They also refer to the following definition as a kind of interdisciplinary consensus:

Spirituality is a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions and practices. (Hall et al. 2016:3)

Without any doubt, spirituality is intimately related to belief systems and religious convictions. Religion, then understood as a broad paradigmatic subset of spirituality, must be viewed as a fundamental factor in fostering a spirituality of human well-being.

[E]ncompassing a system of beliefs and practices observed by a community, supported by rituals that acknowledge, worship, communicate with, or approach the Sacred, the Divine, God (in Western cultures), or Ultimate Truth, Reality, or nirvana (in Eastern cultures). (Hall et al. 2016:3)

Due to the factor of spirituality and its connectedness to religious convictions, it will be argued that God-images play a detrimental role in fostering spiritual healing in patients' response to inexplicable and painful experiences in life. Spiritual distress sets in when patients cannot connect their belief system and framework of meaning to their relational network and personal response to the ailment or disease. In this regard, anger is also viewed as a 'spiritual' and 'religious' phenomenon.

In pastoral care, anger is often projected onto the X-factor in life. Within existing belief systems and religious paradigms, patients look for a possible cause to blame. In this regard, 'God' is introduced as a possible 'culprit' and accused of unfair treatment. This kind of anger is even existent in worship, prayer and close relationships with God. A classic example is Psalm 44:23-24: 'Awake, O Lord! Why do you sleep? Rouse yourself! Do not reject us for ever. Why do you hide your face and forget our misery and oppression?' (New International Version). Thus, the intriguing question in spiritual care: What is the connection between anger and hope in our human quest for meaning in suffering? How can anger be connected to Christian piety and a compassionate understanding of the passio Dei?

The angry patient in caregiving: Probing into the unrevealed painful narratives of life and the existential complexity of loss, failure, disappointment and frustration

Anger is essentially a very complex existential category. One can argue and say that anger is most of times accompanied by fear, anxiety, a mixture of guilt and guilt feelings. It is connected to feelings of loneliness, loss, grief, dread and melancholia. Anger, as connected to anguish and disgust, can even lead to the desperate position of disgust (nausea) (Sartre 1943): a state of non-hope when facing the absurd. Absurd reasoning admits the irrational, knowing simply that in that alert awareness 'there is no further place for hope' (Camus 1965:35).

Without any doubt, anger intoxicates human health and well-being. It penetrates the very fibres of life and the realm of soulful spirituality. It feeds the ontic levels of meaningful being. It can even lurk as a kind of apathetic resistance towards the challenges of life. In this regard, Søren Kierkegaard emphasises dread as an expression of soulless apathy. Encapsulated between fear and trembling (Kierkegaard 1954), apathy leads to 'the sickness in the inner being of the spirit' (p. 146); it creates a kind of despair that tries to neutralise the fear of death, but, unfortunately, all attempts are in vain.

Within the scope of the article, I want to describe the complexity of anger within the context of clinical settings dealing with an acute and even traumatic awareness of the irreversible character of fate, transience, mortality and often incurable diseases. Anger, in this regard, forms a close alliance with anxiety and the fear of loss and rejection; it features as an ontic-existential response to the limitation of life when facing the factuality of dreadful anxiety and human helplessness (being disempowered) - the threat of mortality, death and dying. This assumption is confirmed by research regarding the link between aggressive behaviour and the presentation of dementia in elderly patients suffering from discomfort, fear (anxiety) and loneliness (Charles, Greenwood & Buchanan 2010:19-20).

A very poignant description of anger as a complex existential and ontic disposition when one needs to face the inevitable fact of death and dying or the helplessness of an incurable disease, is a series of paintings by Pablo Picasso when he had to deal with dread, anxiety and helplessness. Encapsulated by fear and a kind of resisting anger, life becomes a horrific experience.

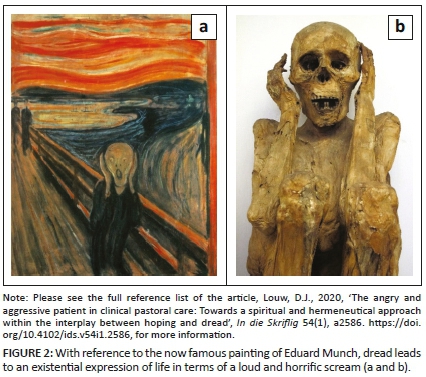

The notion of the painting, The Scream, represents a kind of existential horror that reflects anxiety, as well as resistance and dread (Wikipedia, 2109b). In this Peruvian mummy (Wikipedia, 2109b), the existential dilemma of horror and fear is captured in a very expressive way.

Existential anger can be viewed as a by-product of experiences of being unfulfilled in life, specifically when one faces a threatening fate. It expresses both apathy and helplessness. When one cannot change the impact of dramatic and traumatic events and realises that one must respond appropriately and that it even could contribute to irreversible loss, the frustrating helplessness of anger, as an expression of existential disgust and being unfulfilled, sets in.

In the book, Tuesdays with Morrie (Albom 2000), this phenomenon of disgusting helplessness is aptly articulated. Mitch Albom (2000:118) remarks very aptly: 'Unsatisfied lives. Unfulfilled lives. Lives that haven't found meaning. Because if you've found meaning in your life, you don't want to go back.'

As said, anger is an expression of fundamental existential frustration and is embedded in relational networking. The clinical environment consists of many professional caretakers stemming from different scientific and paradigmatic backgrounds. However, in a team approach, the well-being of the patient as person is the focal area of attention. Whenever caregivers within the different helping professions do not perform effectively according to expectations attached to the specific scientific approach, patients get frustrated. It is indeed true that the source of aggressive behaviour is not always stemming from the clinical setting and could be related to the cultural context or family of origin. Frustration and aggressive behaviour are interpersonal and interrelational, and not necessarily intra-psychic. However, the challenge in caregiving is how to steer away from copying the aggressive responses of the patient, and developing a more mature and appropriate professional stance.

In general, the interpersonal frustration often escalates to aggressive behaviour, because patients have not mastered the assertive behaviours applicable to the condition (Boyd 2001). When anger becomes aggressive, the pain of frustration becomes destructive. Aggression therefore is merely a difference in terms of degree. When anger is transferred into to destructive actions and violent responses, the pain of loss, rejection and disappointment intend to inflict pain on the other. Therefore, aggression is anger expressed in modes of destructive actions of violence; it wants to attack the object of anger in order to exercise power and win control back. To a large extent, aggression becomes a negative coping mechanism; it could be viewed as a personal attempt at self-defence while to a certain extent the external expression of anger is a kind of mask for internalised anxiety and failure to cope with existential dread.

Bessel van der Kolk (2014:2-5) refers to the fact that anger, as linked to anxiety and very traumatic events in the life of a person, should be understood as a many layered phenomenon. Therefore, there is no single approach or instant solution due to many individual different presentations (Bessel van der Kolk 2014:4). He developed therapeutic interventions in neuroscience that utilise the brain's own natural neuroplasticity to help survivors feel fully alive in the present and move on with their lives. He also mentions three avenues that could be explored when dealing with anger due to severe trauma. They are: (1) talking, (re)-connecting with others, and allowing ourselves to know and understand what is going on in us while processing the memories in the brain; (2) by taking medicines that shut down inappropriate alarm reactions; and (3) by allowing the body to have experiences that deeply and viscerally contradict the helplessness, rage or collapse that result from trauma (Bessel van der Kolk 2014:3). In a nutshell: 'Talking, understanding and human relationships help' (Bessel van der Kolk 2014:4).

Due to complexity, the further scope of this article will be to focus on this realm of verbalising the anger by understanding the different connections in terms of a depiction that can help the person to 'see' the bigger picture. The argument will be that such diagrammatic depiction could be quite illuminating in cases where it is possible for patients to put their experience of being helpless, and blocked into more appropriate language (see Figures 1 and 2).

To understand the complexity of the phenomenon of anger, this mood swing can be related to four basic issues in human relationships (see Louw 2008: chapter IV).

-

Unfulfilled needs like the quest for intimacy. One of the most basic needs in human existence is to be accepted unconditionally for whom one is without the fear for rejection. The fear for loss and rejection can be viewed as the most fundamental indication of spiritual and existential pathology. This is what Søren Kierkegaard called dread. Dread is for Kierkegaard the strange phenomenon of sympathetic antipathy; one fears dread and develop in anger an antipathy, but at the same time, what one fears, one desires (Kierkegaard 1967:xii). Without a spiritual dimension and bound merely to dread, as determined by an experience of a bottomless void, life becomes empty, and the person prone to fear and trembling. Human beings become captives of emptiness and destructive anger (Kierkegaard 1954:30). Lurking under expressions of acute anger and aggression is the need for life fulfilment and a secure space of unconditional love. In dealing with anger, caregivers have to deal with the person's experience of loss and dread. Loss could be real in terms of traumatic events in the past. Thus, the necessity of storytelling and probing into traumatic and devastating past events.

-

Unmaterialised expectations and wishes. An experience of existential feelings of being unfulfilled in terms of expectations regarding a meaningful life, leads to internal anger. In the understanding an emotional outburst of anger and aggressive modes of physical abuse, lurks most of the time the pain of disappointment. Existential irritation, frustration and disappointment fuel angry responses.

-

Dysfunctional relationships and inappropriate functions. People are often challenged to meet external criteria without having the appropriate skills, knowledge, education, cultural background, personal capacity and psychic ability to cope with all the demands. An experience of functional inability leads to perceptions like 'I am not good enough'. At the bottom of anger are experiences of failure. These experiences are translated into personal messages regarding identity such as 'I-am-a-failure-in-life'. The outcome is an identity crisis.

-

Destructive feedback and negative messages from educational, familial and career environments. Instead of promoting the other's sense of value and dignity, feedback is most of times in terms of failing, shortcoming, fault and imperfection. In this regard, existing directives based on achievement ethics play a decisive role. One has always to perform in terms of measurable outcomes, determined by production systems and the prosperity cult of success as well as the quest for materialistic, instant happiness.

In a caring environment, one of the most basic therapeutic principles is: Don't address the angry patient, but approach the patient as a person presenting anger as a response to possible harmful settings in life. Being angry in order to probe into the possible causes and experiences of irritation, frustration and disappointment is not a personal trait, but a coping mechanism. When the patient is labelled as being difficult, anger is becoming a feature of fixed, personal identity (a default stance). To distance the patient from his or her anger is to convey the therapeutic message: The person is not the problem, but the undergirding experiences of unfulfilled needs, unmaterialised expectations, dysfunctional relationships and destructive systems of feedback are the core issues to be addressed in a therapeutic approach. The fear for loss and rejection, and the need for security and intimacy is the primary condition to be addressed. Thus, the focus is on a safe therapeutic environment in order to express suppressed frustration.

The therapeutic space of free expression in a caregiving environment: Intervention, ventilation and decompression of the heart

Within a more psycho-therapeutic environment, the emphasis in caregiving is on a catharsis as a healthy expression of anger. Intervention becomes paramount when violence and attack on nurses become prevalent (Boyd 2001; Stuart & Laria 2001; Townsend 2005). Violent and aggressive reactions are always at stake due to the fact that patients admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit or clinical environment of intensive care are usually in reaction and in a destructive mood of resistance. Stress acts of physical aggression or violence can occur. Caregivers are most at risk of being victims of acts of violence by patients.

Within a clinical environment, anger is defined as a strong uncomfortable emotional response to provocation that is unwanted and incongruent with one's values, belief systems, convictions and rights. It coincides with a perceived threat by a patient infiltrating his or her private comfort zone. Whether the threat is internal or external, the core experience of frustration can cause violent and aggressive behaviour. The point is that anger occurs in a response to a perceived threat infiltrating basic needs and general expectations regarding benevolence and the quest for meaning and dignity. When the anger is expressed in uncontrolled explosions, it feeds aggressive behaviour. Aggression then refers to behaviour that is intended to cause harm and pain. It could be either physical or verbal.

Moyer (1968) classifies aggression and refers to the complexity of aggression. Noteworthy is fear-induced aggression, that is, aggression associated with attempts to flee from a threat. This kind of aggression is closely related to irritable aggression (aggression induced by frustration and directed against an available target or external object) and territorial aggression (defence of a fixed or specific area against intruders). Instrumental aggression refers to aggression directed towards obtaining some goal, considered to be a learned response to a situation.

When communication becomes stuck and patients cannot express complaints and irritation pertaining to their caring and nursing environment, frustration fuels anger and eventual aggressive behaviour; that is why effective communication strategies are vital to human well-being and benevolence.

What becomes clear in research is that aversive stimulation, the use of coercion, a limited setting and an authoritarian nursing style have been reported as precursors to aggression (Lance et al. 1999 in Duxbury 2005:475). Negative staff interaction, in particular, is increasingly identified as antecedent to non-therapeutic relationships and disruptive communication and thus the reason for creating a positive culture of patience and tolerance. Attempts to facilitate collaboration is decisive in a nursing and caring environment.

In general, one can say that the treatment and management of anger and severe forms of aggression in a medical-clinical environment boil down to drug treatment (sedating medicine in an acute situation to calm the patient and to prevent personal or social harm), effective communication strategies, and intervention strategies that imply education. The patient must be taught that, in the expression of frustration, more appropriate ways of expression exist than trying to inflict harm. Furthermore, cathartic activities that can help the patient to release frustration within a safe and empathetic space (non-authoritarian setting) are decisive in processes of coping with ailments. Another directive in caring is the setting of boundaries and limits wherein the patient needs to discover what kind of behaviour is acceptable and what cannot be tolerated. A contract can be made in order to reward appropriate behaviour and to control unacceptable behaviour. Sessions of debriefing can be useful in order to monitor the process and to review possible progress or setbacks.

The policy behind any intervention strategy and catharsis is to help the patient to discover that anger is a normal human emotion that can be incorporated in the management of crises and personal frustration (Duxbury 2005:470-471). When anger is discovered as a positive source for creating energy to deal more appropriately with threatening situations, aggressive behaviour can be monitored and minimalised in order to limit destructive behaviour.

It should always be taken into consideration that anger is embedded in cultural values and is closely related to virtues, norms, values, belief systems and religious convictions. The research question is thus as follows: Does, for example, the Christian view on life and understanding of the Godhead (God-images) (the spiritual realm of life) help to deal with anger and aggressive behaviour appropriately, or can it even contribute to unhealthy suppression that fuels violent behaviour, resistance and withdrawal?

The spiritual dimension: The dynamic interplay between faith (trust) and anger (torment)

Not all forms of human anger are necessarily negative. Noteworthy, for example, in a pastoral and Christian approach to the problem of ventilating anger and aggression in patient care, is Ephesians 4:26. Paul quotes Psalm 4:5 saying that one can become angry - only do not sin. When injustice and disobedience are at stake, anger is an expression of a 'holy' kind of resistance against evil; it resists unrighteousness, transgression of the law, irreverence and disdain of the creator.

As spiritual category, anger is closely connected to jealousy and the attempt to take revenge (wrath). The terms thymos and orgē within a Hebrew context refers to a volcanic explosion of passion. The idea is that anger can become uncontrollable and thus destructive (Schönweiss 1975:106). In the New Testament, thymos is mentioned together with words like eris [wrangling, quarrelling], zēlos [jealousy] eritheis [selfish ambition, contentiousness] (see 2 Cor 12:20, Gl 5:20) and pikria [bitternes] (Eph. 4:31).

Thymos is described as a destructive mood. It denotes wrath which boils up. Together with orgē, it is destructive wrath that breaks forth (Hahn 1975:107). Within Hellenism, anger, as the expression of unrestrained passion, stood in contradiction to reason (gnome), namely decision on the basis of knowledge and logos [word] - insight as directed by wisdom, that is, a true distinction regarding what really counts in life (Hahn 1975:107). Being orgilos [quick-tempered] (Tt 1:7) is representing a lifestyle of sinful disobedience which is not in line with the New Testament' s directive, namely to love in contrast to anger, wrath malice, slander and foul talk (Col 3:14).

In the publication The gospel of anger, Alastair Campbell (1986:27) poses the question: What to do with anger? It is quite clear that there can be no single answer to the question: Should anger be expressed or controlled? However, the ventilation theory often leads to the fallacy in ventilationism, namely that anger is given such a priority over other managerial skills and the exercise of realistic reflection, as well as exercising self-control that quite unrealistic expectations are attached to the expression of feelings as a route to wholeness. The point is that emotional catharsis and the release of negative emotions should not be overemphasised in therapy.

On the other hand, should anger be bottled-up for God (Campbell 1986:29)? Campbell warns against oversimplification in many Christian circles, namely that anger is an unworthy passion to be controlled at all costs. To deny anger can indeed be unhealthy. Within a spiritual approach, it should be acknowledged that anger is like love - a moral emotion (Campbell 1986:31). Inappropriate moralisation and oversimplification of the 'bottling-up' approach fails to see the difference between uncontrolled catharsis and responsible expression. In a spiritual approach, it is important to acknowledge one's anger in the presence of God and to express anger in an appropriate way. This route is totally dependent on the following question: Who is God in a practical theological approach?

In a practical theological approach to wrath, anger and aggressive behaviour, the response should be mirrored against the background of God's covenantal faithfulness to his covenantal promise: I will be your God. Even if sheer anger is expressed in a kind of accusing prayer, as in Psalm 44:23-24, the expression should be an indication of trust in the faithfulness of God. The notion of the faithfulness of God is the key theological paradigm to a responsible management of anger, namely to internalise the anger as 'my anger', and to decide to be honest with God. One can only blame and accuse 'A God' whom you can trust. Trust in God's faithfulness makes a pious ventilation of anger possible in pastoral caregiving. The righteousness of God (dikaiosynē), which embraces both his orgē [wrath] and also his grace (charis) and compassion or mercy (eleos) (Hahn 1975:112), are basic determinants for a theology of anger expression. The anger of Yahweh is to be appraised as an expression of God's faithfulness, righteousness and grace.

The cornerstone for all forms of pastoral care and counselling is thus based on the notion of ta splanchna, describing a kind of pastoral theology of the intestines (Louw 2016): The mercy and compassion of God as expressed in the suffering of Christ (passio Dei) are often explained in terms of compassionate categories referring to both anxiety and anger (The Scream). The scream of Christ on the cross (divine forsakenness) and the reference to severe existential anguish in Hebrew 5:7 (the agony of Christ accompanied by strong tears and crying or horrific screaming), connect divine compassion to the existential reality of anger and anxiety.

Mercy in the Bible implies a kind of wisdom-rationality informed by principles and values to express righteousness and wise decision-making in situations of severe distress. The intention is to prevent destructive behaviour in order to inflict patience and to open up to kindle hope. Mercy also implies a juridical component (Davies 2001:246) so that fairness instead of aggression should take control of behavioural responses. In this sense, compassion encompasses more than merely emotions on the level of the affective. The passio Dei is also an exemplification of divine resistance linked to fairness and trustworthiness.

Compassion displayed an active and historical presence with people in distress and severe forms of dread. Compassion, as an acknowledgement of the caring, embracing and intimate presence of God, lead to the formation of a holy fellowship of people (koinonia) who would be mindful of the covenant and reverently honour God's name and faithful promises.

As the signifier of a divine quality which can apply also to human relationships, the root rḥm has much in common with the noun ḥesed, which denotes the fundamental orientation of God towards his people that grounds his compassion action. As 'loving-kindness' which is 'active, social and enduring', ḥesed is Israel's assurance of God's unfailing benevolence. (Davies 2001:243)

It becomes clear that wrath and anger can indeed also play a constructive and therapeutic role. Therefore, in admonition (paraclesis) and advice (wisdom counselling), the warning is an expression of sincere compassion in order to inflict peace and promote mindful surrender. The most fundamental theological notion in pastoral care for the angry patient is the faithfulness of God's covenantal encounter as space for honest ventilation and even brute expression of anger. In this regard, the Job narrative is most appropriate: 'Thou he slay me, yet will I hope in him' (Job 13:15). And then the outburst of anger: 'Why do you hide your face and consider me your enemy? Will you torment a wind-blown leaf? Will you chase after dry chaff?' (Job 13:24-25). To embrace anger in a positive way is to acknowledge in dread, vulnerability and suffering the impact of loss, and to use the loss to reach out to the suffering of others in order to embrace dread as an opportunity to grow from resistance to surrender and compassion. This approach creates hope in anger.

In spiritual healing, believers need to know God in mystery - even in dread and despair. 'There was no answer to Job - but in his angry questioning he met God. We could not ask for more from our gospel of anger' (Campbell 1986:107).

The further argument will be that this 'knowing of God' presupposes a hermeneutical and diagnostic process in caregiving that does not explain the complexity of the interplay between anger and anxiety in a patient's response to dread. Instead of an explanatory approach, a hermeneutical approach is proposed that can help both caregiver and supplicant to understand the complexity of anger even without a rational explanation or positivistic attempt to link the compassion of God (passio Dei) directly to the traditional theodicy discourse (see Louw 2016:303-313), that is, the attempt to link human suffering (even evil) to the will and provision of God - defending and justifying God in light of existing, inexplicable suffering and the treat of fate.

Dealing with anger in a pastoral hermeneutics of hope care: Towards a diagnostic approach and the design of diagrammatic depictions

Hope-giving care within a clinical context of caregiving, implies the following:

-

Helping the caregivers and nursing staff to distinguish between the expression of anger, and the patient as a unique human being. The patient is always more than the sum total of his or her emotional explosions and aggressive behaviour. Therefore, in the first place, do not focus on the responses to sickness and ailments, but to the person suffering from ailments, pain and impairments.

-

Try to boil down to the basic frustration and disappointment as core issue within the turmoil of emotional vulnerability and inappropriate reactions. Never take insults and aggressive attacks personally but focus to the problem and not to the problematic reactions.

-

Move away from an authoritarian stance of control to an empathetic space of compassion. Despite compassion and intimacy, it is always important to maintain a kind of emotional distance between the caregiver and the patients without withdrawal and rejection.

-

Create a space for honest communication so that the patient can start to take up responsibility for inappropriate responses. Anger is therefore a moral emotion and should be transformed into positive behaviour such as acknowledgement of inappropriate behaviour and being prepared to start asking appropriate questions: What happened that I am so frustrated and disappointed in existing relationships? What expectations did I nurture, and are there any reasons why they did not materialise? What were the hampering factors?

-

Boundaries should be set. A discussion on appropriate behaviour and inappropriate expression is paramount. There are limitations in clinical caregiving that patients should adhere to. In this regard, contracting and positive reward for constructive behaviour should be acknowledged. Positive feedback could serve the purpose of sustainable motivation.

-

Deal with the spiritual realm. Is there any unfinished business that caused the current presentation of anger? Do you feel that you failed in life? Is it possible to accept the current situation of illness and to design new short- or long-term gaols? What other options are still meaningful to explore?

-

Probing into spiritual sources such as religious convictions and contact with a Godhead is decisive in pastoral caregiving. Religious sources should be explored in order to identify support systems for constructive moral behaviour the appropriate expression of anger. If the person believes, pastoral caregiving should address the realm of appropriate and inappropriate God-images. Who is God in this person's predicament of frustration and disappointment? In this regard, bottling-up before God can cause spiritual pathology. God-images attached to authoritarian omni-categories (pantokrator-images), should be discussed in order to detect whether they are helpful (kindling hope) or harmful (encourage bottling-up and contribute to anxiety, despair, dread and feelings of rejection and remoteness).

-

In stirring Christian hope, it must be made pretty clear that hope is not about wishful thinking and the taking of opportunistic chances with God. The Christian hope is based on the notion of the pity of a faithful and merciful God as expressed in the weakness of the suffering God (theologia crucis and its connection with the cry or horrified scream of forsakenness - the theopaschitic dimension in human suffering as related to the passio Dei). The proof of the future and eschatological character of the Christian hope reside in God's victory over dread and death - theologia resurrectionis. Hope, resulting from a theology of the cross and a theology of the resurrection, implies the following: Hope is about a new condition of being and a new state of mind. It leads to the New Testament's notion of parrhesia - boldness of speech and the courage to be. Hope is to persist in patience and to see the unseen realm of the faithfulness of God - the realm of faith.

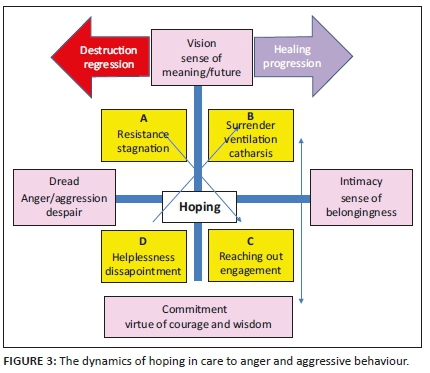

In order to put the previous directives into a praxis approach, namely to start seeing the bigger picture in a hermeneutical design in order to gain insight regarding the networking dynamics of anger in patient care, the following diagrams have been designed (Figures 1 and 2) as a kind of diagnostic tool in a spiritual assessment. The assumption in the following diagrams is that the complexity of the networking anger-anxiety interplay should be understood within the bipolar dynamic networking of vision (the perspective of meaning, significance and future hoping), the existential need for intimacy - a sense of belonging and unconditional love, and the epistemological notion of wisdom (sapientia) that leads to true commitment and the courage to be.

With reference to the spiritual and religious dimension in a diagnostic-hermeneutical model, as well as the paradigmatic framework of a pastoral and theological approach to the existential experience of dread, the undergirding assumption is based on the following four premises that demarcate the disciplinary framework of pastoral caregiving in a Christian and biblical approach:

-

Aggression and anger should be related to divine forsakenness as expressed in a theology of the cross (theologia crucis) and portrayed by the God-image of a suffering, horrified, screaming God (The Scream of God the Son).

-

Vision should be related to the God-image of faithfulness as expressed in a theology of the resurrection (theologia resurrectionis): Epanggelia as indication of the fulfilment of God's promises to care and to console.

-

The existential need for intimacy, embracement and a sense of belongingness to the mercy and compassion of God as exemplified in a theology of the intestines (ta splanchna).

-

The aspect of commitment and the notion of the courage of being to the concept of parrhesia and its connection to wisdom counselling (sapientia) with its moral and religious dimension of trust and faith (the obligations of trusting as based on the charisma of the Spirit - the pneumatological dimension of the epanggelia).

The following diagrams are developed to help caregivers to develop a deep sense of understanding and to enhance their hermeneutical skills. Patients suffering from existential trauma who their concern for being confused and need for more clarity, can also benefit. 'Seeing the bigger picture' can help them to develop a more constructive approach to the complexity of anger. In cases where patients cannot communicate in a meaningful and logical way, as for example elderly patients suffering from severe dementia or Alzheimer's disease, the argument will be that the hermeneutical and diagnostic framework can help the professional team to respond not in a destructive way, but in a compassionate and dignified way, that is, not to focus on the aggressive responses, but on the patient as human and a being with a soul.1

Diagrams as diagnostic tools for fostering processes of hoping in care to the angry patient

Statement 1

Healing and therapy is to help the patient to 'see' the bigger picture of the complexity of anger. Hope is then a new condition of being and mindfulness; it is about exploring other and new options (goal-setting and decision-making). By 'seeing' and discovering what is going on within the frustration and disappointment (experiences of loss and shrinking of bio-psychic capacities) can help the patient to come up with possible new decisions. If the patient is capable of some form of rational insight and the ability to differentiate, kindling of hope is attached to insight regarding possible options and alternatives, that is, the option to change one's disposition or attitude. In the case of resistance, the option is to shift from position A (resistance) to the opposite quadrant C (reaching out), namely to engagement and constructive acts of diakonia. In the case of D (helplessness), the challenge is to shift from disappointment and hopelessness or failure, to ventilation and surrender (B catharsis). In applying 'the bigger picture', hope shifts from sheer opportunism to the realism of resistance and surrender.

The shifting of positions (attitudinal change) is exercised with the systemic bipolarities of the horizontal axis: dread and the quest for intimacy. The other directive is the bipolar tension on the vertical axis between commitment (the making of wise decisions and the ability to differentiate between constructive and destructive behaviour) and vision (a sense of meaning in life and the creativity of imagination). Positions residing in the left quadrants (A and D) mostly contribute to regression and the gradual deterioration of human well-being. Shifting to the opposite quadrants (from A to C; from D to B), contributes to growth and healing.

Theological indicators in hope care to the angry patient

Statement 2

In a praxis approach to the spirituality of hope-giving care, it is decisive to identify inappropriate God-images (God as Pantokrator, God as explanatory causative factor; God as romantic Father Christmas with instant solutions and God as absent judge) and to distinguish them from more constructive images (God as co-sufferer and comforter journeying together in covenantal partnership with the suffering supplicant). Caregivers should help patients wrestling with the following question: Where is God in my predicament? They need to be able to differentiate between inappropriate (the revenging and punishing God) and appropriate God-images (The suffering God; faithfulness of God; embracing God, presence of God). As in the now classic book The practice of the presence of God, Brother Lawrence (1985:19) emphatically said: One should fix oneself firmly in the presence of God by conversing with him all the time - the delight of Christian wisdom.

In their book on Interfaith spiritual care, Schipani and Bueckert (2009:315-319) argue that a pastoral theology of presence is paramount within human encounters with people in severe distress. In this regard, wisdom in theory formation for pastoral caregiving leads to an understanding why being functions are more fundamental than doing, knowing and emotional functions. 'Personal wisdom is also a matter of "being" as well as "being with"' (Schipani & Bueckert 2009:317).

The following diagrammatic depiction helps to detect the interplay and possible therapeutic effect of different God-images and theological and religious assumptions regarding an understanding of the impact of God's presence on human responses. It also describes the dynamics between the expression of anger and possible appropriate or inappropriate images of God. In theology of pastoral caregiving, the question is not so much whether the images are right or wrong (the moral approach), but whether the images (even the so-called inappropriate images) foster wise decision-making and the process of finding hope and a constructive expression of anger.

By inappropriate God-images are meant depictions and prescriptive doctrinal formulae that portray God in terms of all-powerful categories such as omnipotence and omniscience. These categories are mostly based on remote authoritarian interpretations of super-power pantokrator-images rather than inspired by the comforting and consoling categories of grace, pity and mercy. Pantokrator is the Greek version of the Hebrew El Shaddai. The latter refers to the splendid and unique majesty of God as displayed in his covenantal grace and trustworthy faithfulness. However, God-images reflecting a kind of all-powerful Caesar-God or causative factor behind the happenstances of life (an explanatory) model, do not comfort and are insufficient to instigate sustainable hope. They also do not bring closure and consolation. It is also dangerous to portray God as a kind of Father Christmas that reward obedient children and guarantees happiness, success and 'good luck' (the God of a prosperity cult).

It is often the case that in suffering and disappointment, people experience God as remote and absent. However, such experiences are related to painful human conditions and disturbed emotional filters of torment and severe dread. The God of compassionate companionship (I-will-be-your-God-wherever-you-are) cannot be too far or too near. Distance categories are inappropriate in a pastoral hermeneutics. It is here that categories of mercy like ta splanchna are most meaningful in order to foster sustainable modes of hoping.

Conclusion

Anger is a mood swing with possible moral implications. It can create positive energy in order to enhance coping mechanisms that use different crises in life as opportunities for growth, insight, meaning-giving and constructive hoping. However, uncontrolled expressions within cathartic interventions can cause harm to both the patient's sense of dignity and the quality of caregiving. In care to the angry and aggressive patient in clinical pastoral care, a safe hospitable space of inmate encounter should be fostered under all conditions. In this regard, patients should be encouraged to ventilate with honesty without experiencing detachment, rejection and enmity from the side of professional caregivers. On the other hand, firmness and discipline should be maintained in order to protect both caregivers and patients. The focus should be on the patient as a person and not inappropriate responses and emotional expressions of anger and aggression.

In a spiritual approach, hope should be kindled. In this regard, compassion as an expression of the passio Dei, can help to create a safe, hospitable haven for weak and vulnerable patients. God-images of a suffering and forsaken God (the theopaschitic model) (Louw 2016:318-338), a reliable, trustworthy and faithful God, a God of mercy and unconditional love - all of them contribute to the spiritual mode of parrhesia: boldness to converse with God, boldness of speech and the courage to be (empowering functions of being) despite progressive experiences of weakness, the inability to communicate and to cope with memory loss and irreversible physical impairments.

The diagrams, designed in Figures 3 and 4, should be viewed as diagnostic tools, that is, as visual portrayals of the complexity of aggressive behaviour in patient care. At the same time, depictions of the networking dynamics and how different issues can be related to the complexity of God-images in spiritual healing, help both caregivers and patients to develop insight. In this sense, 'the spirituality of seeing' promotes believing and contributes to decision-making, attitudinal changes and the healing of destructive, aggressive responses to ailments and irreversible conditions of loss.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that no competing interest exists.

Author's contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical consideration

Ethics approval was granted by the research ethics committee of the university.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Albom, M., 2000, Tuesdays with Morrie, Warner Books, London. [ Links ]

Arthistoryarchive, 2012, Horrified by death, viewed 22 April 2012, from http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/cubism/images/PabloPicasso-Self-Portrait-1972.jpg. [ Links ]

Bessel van der Kolk, M.D., 2014, The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma, Penguin Books, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Boyd, M.A., 2001, Psychiatric nursing contemporary practice, Lippincott Publications, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Brother Lawrence, 1985, The practice of the presence with God, Hodder & Stoughton, London. [ Links ]

Campbell, A., 1986, The gospel of anger, SPCK, London. [ Links ]

Camus, A., 1965, The myth of Sisyphus, Hamish Hamilton, London. [ Links ]

Charles, J., Greenwood, S. & Buchanan, S., 2010, Responding to behaviour due to dementia: Achieving Best Life Experience (ABLE). Care planning guide, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Veterans Centre, Toronto, viewed 08 December 2019, from https://sunnybrook.ca/uploads/ABLE_CarePlanningGuide.pdf. [ Links ]

Davies, O., 2001, A theology of compassion. Metaphysics of difference and the renewal of tradition, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Duxbury, R.W., 2005, 'Causes and management of patient aggression and violence: Staff and patient perspectives', Journal of Advanced Nursing 50(5), 469-478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03426.x [ Links ]

Hahn, H.C., 1975, 'Anger, indignation, wrath (orgē)', in C. Brown (ed.), Dictionary of New Testament Theology, pp. 107-113, The Paternoster Press, Exeter. [ Links ]

Hahn, P., 1971, Der Herzinfarkt in psychosomatischer Sicht, Verlag für Meditinische Psychologie, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Hall, E.J., Hughes, B.P. & Handzo, G.H., 2016, Spiritual care: What it means, why it matters in health care, Health Care Chaplaincy Network, New York, NY, viewed 08 December 2019, from https://healthcarechaplaincy.org/docs/about/spirituality.pdf. [ Links ]

Hayes, R.B., 2003, 'The Christian practice of growing old: The witness of scripture', in S. Hauerwas, N. Mark & S. Wells (eds.), Growing old in Christ, pp. 3-8, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Kierkegaard, S., 1954, Fear and trembling and the sickness onto death, Doubleday, New York, NY. [ Links ]

Kierkegaard, S., 1967, The concept of dread, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. [ Links ]

Louw, D.J., 2008, Cura vitae: Illness as crisis and challenge, Lux Verbi, Wellington. [ Links ]

Louw, D.J., 2016, Wholeness in hope care: On nurturing the beauty of the human soul in spiritual healing, Lit Verlag, Zürich. [ Links ]

Moyer, K.E., 1968, 'Kinds of aggression and their psychological basis', Communications in Behavioral Biology 2, 65-87. [ Links ]

Ryan, E.B., L. S. Martin & A. Bearman. 2005, 'Communication strategies to promote spiritual well-being among people with dementia', The Journal of Pastoral Care and Counselling 59(1-2), 44-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/154230500505900105 [ Links ]

Sartre, J.-P., 1943, L'Être et le Néante, Gallimard, Paris. [ Links ]

Schipani, D.S. & Bueckert, L.D., 2009, 'Introduction', in D.S. Schipani & L.D. Bueckert (eds.), Interfaith spiritual care. Understanding and practices, pp. 315-319, Pandora Press, Kitchener. [ Links ]

Schönweiss, H., 1975, 'Anger, wrath (thymos, orgē)', in C. Brown (ed.), Dictionary of New Testament Theology, pp. 105-106, The Paternoster Press, Exeter. [ Links ]

Stuart, G.W. & Laria, M.T., 2001, Principles and practices of psychiatric nursing, Mosby Publishers, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Townsend, M.C., 2005, Psychiatric mental health nursing concepts of care, F.A. Dais Company, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Van Dyk, A., 2008, HIV/AIDS care and counselling: A multidisciplinary approach, Pearson Education, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Weich, H.F., 1982, 'Die pasiënt met 'n hartaanval', in D.W. de Villiers & J.A.S. Anthonissen (reds.), Dominee en dokter by die siekbed, pp. 90-96, NG Kerk-Uitgewers, Kaapstad. [ Links ]

Wikipedia, 2019a, Museo di storia naturale (Florence) - Anthropology and Ethnography section - Peru, viewed 08 December 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Scream#/media/File:Mummie_di_cuzco_04.JPG. [ Links ]

Wikipedia, 2109b, The Scream, viewed 08 December 2019, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Edvard_Munch,_1893,_The_Scream,_oil,_tempera_and_pastel_on_ cardboard,_91_x_73_cm,_National_Gallery_of_Norway.jpg#filehistory. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Daniël Louw

djl@sun.ac.za

Received: 09 Dec. 2019

Accepted: 06 Apr. 2020

Published: 19 Aug. 2020

1 . The author developed the model in terms of his 5-year involvement as minister and caregiver within a clinical setting of a frail care unit (Paradys Palm, Paradyskloofvillas and Stellenbosch). In this design, the methodology of participatory observation played a fundamental role in the diagnostic-hermeneutical approach. It was tested several times on caregivers and personnel of the frail care unit during several sessions of training and group discussions. Due to reality of the demands within the frail care unit, personnel asked me to develop such a tool in order to help them to understand their own emotional resistance to patients' aggressive behaviour.