Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

In die Skriflig

On-line version ISSN 2305-0853

Print version ISSN 1018-6441

In Skriflig (Online) vol.54 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ids.v54i1.2528

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The Holy Spirit's characterisation of the Matthean Jesus

Francois P. Viljoen

School for Church Ministry and Leadership, Faculty of Theology, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article contributes to the discourse on the characterisation of Jesus in the Matthean Gospel. Characterisation can happen in several ways, for example by letting the characters themselves act and speak, or by letting other characters talk about them or react towards them. It can also be done by a narrator who tells the reader about a character. The kind of character depends on the traits or personal qualities of that character and how that character performs in specific circumstances. Along with God himself, Jesus forms the principal character in the first gospel. His teachings and actions form the focus of attention, and the actions of other characters are directed at him. This article focusses on one aspect of characterisation, namely on how the Holy Spirit acts in support of Jesus. The evangelist utilises the actions of the Holy Spirit as a narrative strategy to gradually express the significant status of Jesus as main character.

Keywords: narrative criticism; historical narrative; characterisation; Jesus; Matthew; narrative; Holy Spirit.

Introduction

Reading gospels as narratives1 mainly involves two aspects: The one is to study the content of the narrative, in other words, what is told - the 'story'. The other is to investigate how it is told; which rhetorical techniques are employed - the 'discourse' (Carter 1997:3; Kingsbury 1986:2; Stock 1994:3).2

The 'story' of a narrative includes events, setting and characters (Kingsbury 1986:9; Powell 2009:45-52; Viljoen 2018:8). Authors bring characters3 to life by way of characterisation (Anderson 1994:78; Bauer 1992:357; Powell 1990:51; Tolmie 1999:41). Characterisation can take place by letting the characters themselves act and speak, or by letting other characters talk about them or react to them. The author can also make use of a narrator who tells the reader about a character (Anderson 1994:78-80). The kind of character depends on the traits or personal qualities of that character (Powell 2009:48). The individual status of a character is defined in terms of the person's relation to the main and other characters. Characters are involved in the incidents that are narrated. The features of a character should be interpreted in terms of the specific incident and the context of this incident (Edwards 1997:13; Tolmie 1999:42).

A variety of characters feature in Matthew's Gospel. Characters can consist of individuals, such as John the Baptist, or character groups, such as the Pharisees or crowds. Characters can be human, though anthromorphic beings, such as animals, can also act as characters. Along with God himself, Jesus is the single main character, the protagonist,4 in the Gospel. From the very beginning, He is introduced as the Son of David (Mt 1:1), Immanuel (Mt 1:23), and the Son of God (Mt 2:15). There are only a few instances where he is not the main actor in the 'scenes'. However, all 'scenes' are related to Jesus. His teachings and actions form the focus of attention and the actions of other characters are directed at him. Matthew abbreviates his Markan source so that Jesus's words are in the foreground at all times (Luz 2007:17; Powell 1990:54; Weren 1994:12).5

This article investigates one aspect of the characterisation of the Matthean Jesus, namely how the Holy Spirit acts in support of Jesus. The aim of this article is to demonstrate how the evangelist utilises the character of the Holy Spirit to communicate traits of Jesus. The involvement of the Spirit with Jesus is narrated in several instances, namely with the 'genesis' of Jesus, his baptism, when leading Jesus into the wilderness and with the Holy Spirit being bestowed upon him.

'Generating' Jesus

The first reference to the Holy Spirit occurs in the short narrative (Mt 1:18-25) that serves as commentary on the genealogy (Mt 1:1-17). Similar schemas of the birth announcement occur in the Old Testament (e.g. Gn 16:11; 17:19; Jdg 13:3-5; Is 7:14). Such announcements are related to the birth of important figures in the history of Israel, and are repeated with the birth of Jesus (Luz 2007:92).

Matthew 1:18-25 explains the virginal conception and birth of Jesus.6 Jesus's conception is told to be the work of the Holy Spirit 'ἐν γαστρὶ ἔχουσα ἐκ πνεύµατος ἁγίου' [she became pregnant through the Holy Spirit] (Mt 1:18) and 'τὸ γὰρ ἐν αὐτῇ γεννηθὲν ἐκ πνεύµατός ἐστιν ἁγίου'·[because what is conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit] (Mt 1:20). This creative agency of the Holy Spirit does not explain how Jesus was born. According to Thomas Aquinas, Jesus is the creatura of the Holy Spirit (Lectura no. 111). The Holy Spirit is not the father of Jesus. Jesus is generated not by the 'substantia', but by the 'virtus' of the Holy Spirit (Dionisius bar Salibi 1.55 remarked: 'Believe! Believe strongly! Do not question. Neither Gabriel nor Matthew was able to say how this happened'). The repetitive use of γένεσις-related lexemes in Matthew 1:1, 1:17c and 1:18 is significant as they echo the creation motifs of Genesis 1 and 2. The Holy Spirit is the agency in God's creative power (Stock 1994:28). It seems that the 'genesis' of Jesus by the Holy Spirit alludes to God's creative power through the Holy Spirit7 during creation.

The role of the Holy Spirit is emphasised by the way Matthew alludes to Isaiah 7:148 in his first fulfilment citation. This citation is particularly solemn: 'Ἰδοὺ ἡ παρθένος ἐν γαστρὶ ἕξει καὶ τέξεται υἱόν, καὶ καλέσουσιν τὸ ὄνοµα αὐτοῦ Ἐµµανουήλ ὅ ἐστιν µεθερµηνευόµενον Μεθ' ἡµῶν ὁ θεός' [Behold, the virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel, which means 'God with us'] (Mt 1:23). The Hebrew texts use 'almah', which means a young woman of marriageable age, and not 'betulah', which means a virgin. The Septuagint (LXX) and Matthew 1:23 translates 'almah' with 'ἡ παρθένος' [the virgin], confirming that she had not had sexual relations (Talbert 2010:34). Jesus's miraculous conception is presented as the fulfilment of this prophecy by Isaiah, but it happens in a miraculous manner as Mary becomes pregnant by the Spirit. Matthew adds 'πνεύµα', as reference to the Spirit does not occur in Isaiah.

This recurring reference to the Spirit characterises the baby to be born. It demonstrates Jesus's unique character and how this came to be. His uniqueness is further emphasised by the fact that Mary is called the mother of Jesus, but Joseph is not called his father. God is his Father.9 His conception by the Holy Spirit identifies Jesus as Son of God. In early Christian thought, the Holy Spirit was closely linked to eschatological sonship (Jn 3:5; Rm 8:9-17; Gl 4:6, 28-29; Davies & Allison 2004a:2001). The question then arises as to how the genealogy of Joseph could be applied to Jesus. According to Jewish practice, Joseph's naming of the baby constituted legal recognition of the child as his own (Mishna Baba Batra, 8.6).10 Jesus was 'God with us' through the Holy Spirit, while legally being Joseph's son (Stock 1994:29).

The involvement of the Holy Spirit in Jesus's 'genesis', reveals the unique character of Jesus. It tells readers who Jesus is and how he became this. His high status is emphasised. From his conception, he is endowed with the Holy Spirit. Although he is born from a human mother, he is the Son of God. He is Immanuel - 'God with us'.

Descending on Jesus like a dove

Jesus's status is confirmed when the Holy Spirit descends upon him when he comes out of the water after his baptism. The evangelist states that the heavens 'were opened', which probably alludes to the significant vision of Ezekiel in 1:1-4 (Stock 1994:4). However, what happened at Jesus's baptism is portrayed as a visible event and not as a vision (Luz 2007:143). As the Holy Spirit descended upon David when Samuel anointed him as king (1 Sm 16:13), so does the Spirit descend upon the son of David. Jesus is anointed and empowered as the messianic king (Talbert 2010:57). The Jews would have regarded this as the fulfilment of the expectation of the relationship between the Spirit and the Messiah (cf. Is 11:2; Pss Sol 17:37; 1 En 49.3; 62.2).

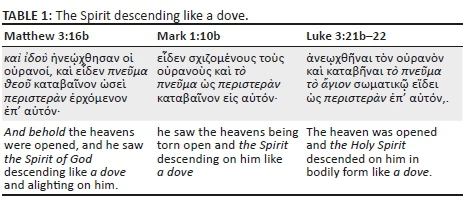

All three of the Synoptic Gospels narrate this descent of the Holy Spirit as indicated in Table 1. While Mark only refers to τὸ πνεῦµα [the Spirit], Matthew adds that it is the Spirit of God, while leaving out the article (πνεῦµα θεοῦ).11 Luke retains the article and adds that the Spirit is the holy one (τὸ πνεῦµα τὸ ἅγιον) and that the Spirit came down as a dove (ὡς περιστερὰν).

This vision of the descending dove seems to hark back to the Spirit of God hovering over the waters in Genesis 1:2 and Noah's dove (Gn 8:8-12). Yet, there is probably more to it. Several ancient authors have noted that when gods gave testimony on matters, their voices were confirmed by visions from the heavens (Talbert 2010:57). Cicero (Top 20.76-77)12 mentions among such signs the flight of birds in the air. The philosopher, Pythagoras, taught his disciples on bird omens and regarded birds as messengers from the gods sent to those whom the gods truly love (Lamblichus, Vit. Pythagoras, 6.1).13 In Persia, a dove was regarded as a royal bird and symbol for the divine power that filled a king (Luz 2007:143). In the proto-evangelium of James (9.1),14 Joseph received a rod and a dove came out of the rod and flew onto Joseph's head. This sign was followed by the words of the priest: 'Joseph, to you has fallen the good fortune to receive the virgin of the Lord.' In the Synoptic Gospels both the descent of the Holy Spirit as a dove and the voice from heaven are reported. An ancient Mediterranean reader would recognise this vision and voice as God's testimony to legitimise Jesus as the worthy eschatological bearer of God's Spirit (Davies & Allison 2004a:335; Viljoen 2019:2). Prophesies regarding the coming of the Messiah and the Spirit are fulfilled (cf. Is 11:2; Jl 2:28-29; Ps Sol 17:37; 18:7). The Matthean version adds the unique interjection 'καὶ ἰδοὺ' [and behold] with reference to this vision. This word and its Hebrew equivalent (hinneh) points to the unexpected and is associated with angelic appearances and theophanies (e.g. Gn 18:2; 28:13; Ezk 1:4; Jdg 14; Rv 19:11; Davies & Allison 2004a:206). Matthew emphasises the significance of this vision.

Several of Jesus's character traits can be recognised during this event. The most outstanding traits are the following: He is a figure with a very high status; he is the mighty one John said he would be, the one specially loved by God; he is the preeminent Son of God; he is the fulfilment of the long-awaited messianic expectations; he is empowered by God for his messianic ministry, which would shortly begin; and he would minister with God-given authority.

Leading Jesus into the wilderness

After the legitimation of Jesus as God's son, Jesus is led into the wilderness by the Spirit.15

All three the Synoptic Gospels narrate this event as indicated in Table 2. While Mark uses the active voice (the Spirit led him out to the wilderness) and Luke the middle or passive voice 'he was led by the Spirit', Matthew uses the passive (Jesus was brought up to the wilderness by the Spirit). Similar to Mark, Matthew uses an article with 'Spirit', clearly indicating the Spirit as person. Being led by the Spirit signifies that Jesus is in total submission to the will of the Father. This submission of Jesus is a further testimony of his 'fulfilment of all righteousness' as demonstrated with his baptism (Mt 3:15).16

It seems that this conduct of the Spirit alludes to the exodus and wilderness experiences of Israel. Similar to when Jesus came out of the water and was led into the desert to be tested, God led Israel out of Egypt and through the waters into the desert (Dt 8:2, 5; cf. Floor 1969:35). God tested his 'son Israel' (cf. Ex 4:22-23) in the desert for 40 years to humble them after they emerged from the Red Sea (cf. Dt 6:10-19; 8:1-10; 1 Cor 10:1-18).17 In Jewish and Christian thought, the desert was regarded as the haunt of evil spirits (Lv 16:1, Mt 12:43 // Lk 11:24). During Israel's testing, the Spirit of God was also particularly active (Nm 11:17, 25, 29; Neh 9:20; Ps 106:33; Is 63:10-14). While Israel's history is largely one of failure, Jesus remains steadfast in his fidelity towards God.

It was a common part of Jewish tradition that persons chosen by God are tested as illustrated by the lives of Job (cf. Job 1-2) and Abraham (cf. Gn 22). In the same vein, Sirah 2:1 states: 'My child, when you come to serve the Lord, prepare yourself to be tested.' Once persons have committed themselves, they are tested (Talbert 2010:60). Three times18 the Satan tests Jesus's obedience to God, hoping to entice Jesus to break his faith with God and thus to renounce his sonship. In testing Jesus, Satan deceitfully adopts God's words, 'Son of God'. In all three of these tests, the devil tempts Jesus to misuse his power. Jesus does not succumb to these temptations and the devil leaves. Jesus's authority eventually comes from God and not from the devil (Mt 18:18).

This short narrative once again demonstrates Jesus's character traits. As Son of God, he is the supreme agent of God. Being chosen by God, he is willing to fulfil all righteousness. He subjects himself and is led out into the wilderness. He comes in conflict with Satan and overcomes the temptations set by the devil. He does not misuse his power. While remaining fully devoted to the Father when tempted, similar to what Israel experienced in the wilderness, he reverses Israel's disobedience with his victorious dealings with the devil.

Being upon Jesus

Following Jesus's healing19 of the man with the shrivelled hand on the Sabbath and the disgust of the Pharisees with this, Matthew 12:17 declares Jesus's ministry as the fulfilment of the prophecy of Isaiah 42:1-4 (Viljoen 2011:7). He does this in a 'targumized' manner as to provide a Christological interpretation of this Old Testament passage (Davies & Allison 2004b:328). Although this quotation is directly linked to Jesus withdrawing, this passage reveals the character of Jesus in a significant manner.

This quotation applies to Jesus's character and ministry. The introduction to this quotation (Mt 12:15-16) is structurally reminiscent to Matthew 8:16-17, as both of these passages provide a summary of Jesus's healing activity. Closely linked to this healing ministry in Matthew 12, this summary is followed by a quotation from Isaiah 42:1-4. This is the longest of all Old Testament quotations in Matthew, and is found in this gospel only. This formula quotation could have been taken from a pre-Matthean testimonium or could be Matthew's independent translation of the Hebrew with some influence from the LXX and the Targum, which he adapted to fit the Christological context of the gospel (Davies & Allison 2004b:322; Luz 2007:192).

The quotation consists of five pairs that partly form parallelisms as indicated in Table 3. The quotation begins with God speaking in the first person (Mt 12:18a) and then immediately moves to statements about the 'child' (Mt 12:18b-21).

The words of God, Ἰδοὺ ὁ παῖς µου ὃν ᾑρέτισα, ὁ ἀγαπητός µου ὃν εὐδόκησεν [Behold, here is my Son whom I have chosen, the one I love, in whom my soul delights] underscore Jesus's status. These words resemble the divine words after his baptism: οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ υἱός µου ὁ ἀγαπητός, ἐν ᾧ εὐδόκησα [this is my Son whom I love, in whom I delight] (Mt 3:17), on the occasion of Jesus being endowed with the Spirit, and at his transfiguration, οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ υἱός µου ὁ ἀγαπητός, ἐν ᾧ εὐδόκησα· ἀκούετε αὐτοῦ [this is my Son whom I love, in whom I delight. Listen to Him] (Mt 17:5) where his status as suffering servant is exemplified. By assimilating these two key Christological references, Matthew lifts the Christological importance of this servant quotation to the same level as that of the other two. By linking this quotation with the voice of God after Jesus's baptism, Matthew implicitly claims that the Messiah's mission as inaugurated with his baptism is now being fulfilled in the Son of God (France 1998:206).

Significantly, Matthew renders the Hebrew ''ebed' not with 'δοῦλος' [slave] or 'διάκονος' [servant], but with 'παῖς' [son], similar to the LXX. The Father expressly identifies Jesus as his Son (Chamblin 2010:653).20 'Παῖς' is a more comprehensive title than 'δοῦλος' or 'διάκονος'. It implies more than Jesus's passion to include his entire ministry. Jewish-Christian texts use this designation with reference to the expected Messiah (cf. Ascension of Is 1:4; 3:13; Testament of Benjamin, 11). Identified as the Messiah, God's Spirit rests upon him for this special task of bringing deliverance. Matthew moves the focus from a 'servant of God Christology' to a 'Son of God Christology' (Luz 2001:193).

The Son is further identified as 'ὁ ἀγαπητός µου ὃν εὐδόκησεν' [my beloved in whom I delight]. While the Pharisees condemned Jesus and plotted how they could kill him (Mt 12:2, 10 and 14), God loves him and takes delight in him (Mt 12:18). While the Pharisees are deeply displeased with Jesus, God is well pleased.

The Spirit has been put on him. Matthew replaces 'ἔδωκα' of the LXX Isaiah 42:1 with 'θήσω'. Being endowed by the Spirit, Jesus acts as a patient, peaceful, kind and loving Messiah. The quotation explains Jesus's conduct: κρίσιν τοῖς ἔθνεσιν ἀπαγγελεῖ [He will proclaim justice to the nations] (Mt 12:18). He will lead justice to victory (Mt 12:9). Κρίσις implies an imminent judgement and victory of justice, while ἀπαγγελεῖν is associated with the heralding of good news about Jesus. The judgement brings hope for the nations. In his name, the nations (ἔθνη) would put their hope (Mt 12:21). This quotation refers to Gentiles21 twice, which fits well with Matthew's interest (Davies & Allison 2004b:323-324). In contrast to the exclusivity of Jews, the first gospel offers Gentiles an open door.22 Luz (2007:84) proposes that Matthew elected himself as advocate to defend his community's decision in favour of the Gentile mission.

Jesus's humility and gentleness for the poor and the needy is stated: οὐκ ἐρίσει οὐδὲ κραυγάσει … κάλαµον συντετριµµένον οὐ κατεάξει [He will not quarrel and cry … a bruised reed He will not break] (Mt 12:19-20). This reaffirms Jesus's declaration in Matthew 11:28-30. His conduct is different from the belligerent Messiah that was popularly expected23 (Chamblin 2010:654). He has compassion with all, especially the weak and vulnerable - people on the edge of society as represented by the tax collectors and sinners (cf. Mt 9:9-12).

The pericope that follows this quotations (Mt 12:22-37), elaborates on the theme of the Holy Spirit and Jesus (cf. Mt 12:28). Anointed by the Spirit, Jesus demonstrates the inauguration of his kingdom by exorcising demons. He proves to his opponents that he possesses the Spirit (Mt 12:28, 32).

Several traits of Jesus's character can be recognised in this passage. Jesus has a special relationship with God, being his beloved Son. Chosen by God, he performs the messianic salvation task. He is meek and humble, doing this task not with loud outcries, harshly or recklessly. He shows mercy to all humans, fulfilling the hope of all peoples. He leads them to victory, although through judgement. He does this as one who is filled with God's merciful and sanctifying Spirit.

Conclusion

The evangelist narrates four scenes where the Holy Spirit interacts with Jesus, supporting him as the main character in the gospel. He emphasises that Jesus's mission is inspired by the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit acts as a reliable character witness. From this interaction, several of Jesus's traits can be recognised.

The Holy Spirit is a witness to the preeminent and unique character of Jesus. Jesus is born of the Spirit with no involvement of a human father. He became 'God with us'. The foremost position of Jesus is based on his unique relationship with God. With the baptism of Jesus, the heavens open and the Holy Spirit descends on Jesus like a dove to underscore God's voice from heaven, which is identifying Jesus as his beloved Son. The Holy Spirit confirms that God identifies, characterises and authorises Jesus in relation to himself.

The Holy Spirit witnesses to the fact that Jesus is commissioned by God. Jesus is endowed by the Spirit to perform his mission as the long-awaited Messiah. This is confirmed with the visible appearance of the Holy Spirit after Jesus's baptism. The Spirit bears witness to the legitimate status and worthiness of Jesus as the eschatological bearer of God's Spirit. Jesus's status is once again confirmed in the scriptural quotation from Isaiah, stating his endowment with the Spirit. He is identified as the Messiah, because God's Spirit rests upon him for this special task of bringing deliverance.

In its interaction with Jesus, the Holy Spirit demonstrates how Jesus submits to the will of God. Jesus fulfils all righteousness by allowing the Holy Spirit to lead him into the desert to be tempted by the devil. He remains faithful to his Father despite the repetitive and deceitful temptation by Satan. He reverses Israel's disobedience with his victorious dealings with the devil.

As the Holy Spirit leads Jesus to the abode of the devil to be tempted, he demonstrates how Jesus overcomes the deceitfulness of Satan even in his human and vulnerable state after fasting for 40 days and nights. By remaining loyal to God, Jesus reverses Israel's failure when they were tempted in the desert. Jesus has the last word with Satan so that he leaves. He will ultimately beat Satan and all opposing characters.

The Holy Spirit witnesses to the gentle and consoling way in which Jesus handles the weak and lowly, figuratively referred to as the bruised reeds and smouldering wicks. His conduct is different from the belligerent Messiah as popularly expected. Being endowed by the Spirit, Jesus does not cry out, but acts as the patient, peaceful, kind and loving Messiah. He has compassion with all, especially the weak and vulnerable - people on the edge of society.

The Holy Spirit witnesses that Jesus will bring hope to all the nations. In contrast to the common exclusivity of Jews, he offers Gentiles an open door. He shows mercy to all peoples.

While heralding the good news, he would bring judgement to ensure the victory of justice.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Author's contributions

I declare that I am the sole author of this research article.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for carrying out research.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author.

References

Anderson, J.C., 1994, Matthew's narrative web; Over and over again, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Bauer, D.R., 1992, 'The major characters of Matthew's story: Their function and significance', Interpretation 46, 357-367. [ Links ]

Burnett, F.W., 1993, 'Characterization and reader construction of characters in the Gospels', in E.S. Malbon & A. Berlin (eds.), Characterization in biblical literature, Semia, 63, 1-28, Scholars Press, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Carter, W., 1997, 'Narrative/literary approaches to Matthean theology: The "reign of the Heavens" as an example (Matt. 4:17-5:12)', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 67, 3-27. [ Links ]

Chamblin, J.K., 2010, Matthew: A mentor commentary, vol. 1, chapters 1-13, Christian Focus Publications, Ross-Shire. [ Links ]

Culpepper, R.A., 1984, 'Story and history in the gospels,' Review and Expositor 81, 467-478. [ Links ]

De Silva, D.A., 2004, An introduction to the New Testament: Contexts, methods and ministry formation, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Davies, W.D. & Allison, D.C., 2004a, Matthew 1-7, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Davies, W.D. & Allison, D.C., 2004b, Matthew 8-18, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Edwards, R.A., 1997, Matthew's narrative portraits of disciples, Trinity Press International, Harrisburg, PA. [ Links ]

Floor, L., 1969, De nieuwe exodus: Representatie en inkorporatie in het Nieuwe Testament, PU vir CHO, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

France, R.T., 1998, Matthew evangelist and teacher: New Testament profiles, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Genette, G., 1980, Narrative discourse: An essay in method, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. [ Links ]

Gerhardsson, B., 1966, The testing of God's Son (Matt. 4:1-11 & par.): An analysis of an early Christian midrash, Gleerup, Lund. [ Links ]

Greimas, A.J., 1983 [1966], Structural semantics: An attempt at a method, transl. D. McDowell, R. Schleifer & A. Velie, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. [ Links ]

Hays, M.H., 2013, 'Towards a faithful criticism,' in C.M. Hays & C.B. Ansbury (eds.), Evangelical faith and the challenge of historical criticism, pp. 1-23, Baker, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Kingsbury, J.D., 1986, Matthew as story, Fortress Press, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Luz, U., 2001, Matthew 8-20: A commentary, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Luz, U., 2007, Matthew 1-7: A commentary, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Merenlahti, P. & Haloka, R., 1999, 'Reconceiving narrative criticism', in D. Rhoads & K. Syreeni (eds.), Characterization in the Gospels: Reconceiving narrative criticism, Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series 184, 13-48, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Pilch, J.J., 1988, 'Understanding Biblical healing: Selecting the appropriate model', Biblical Theology Bulletin 18, 60-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/014610798801800204 [ Links ]

Powell, M.A., 1990, What is narrative criticism?, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Powell, M.A., 2009. 'Literary approaches and the Gospel of Matthew', in M.A. Powel (ed.), Methods for Matthew, pp. 44-82, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Stock, A., 1994, The method and message of Matthew, The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, PA. [ Links ]

Talbert, C.H., 2010, Matthew, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Tolmie, D.F., 1999, Narratology and biblical narratives: A practical guide, Wipf & Stock, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Viljoen, F.P., 2011, 'Sabbath controversy in Matthew', Verbum et Ecclesia 32(1), Art. #418, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v32i1.418 [ Links ]

Viljoen, F.P., 2018, 'Reading Matthew as a historical narrative', In die Skriflig 52(1), a2390. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v52i1.2390 [ Links ]

Viljoen, F.P., 2019, 'The Matthean characterisation of Jesus by God the Father', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 75(3), a5611. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i3.5611 [ Links ]

Weren, W.J.C., 1994, Belichting van het Bijbelboek, Matteüs, Katholieke Bijbelstichting, 's-Hertogenbosch. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Francois Viljoen

viljoen.francois@nwu.ac.za

Received: 30 July 2019

Accepted: 15 Nov. 2019

Published: 30 Jan. 2020

1 . This literary paradigm in gospel studies should not invalidate historical and theological questions asked to the text (Hays 2013:17; Powell 1990:98; 2009:44). The gospels are non-fictional narratives based on historical events and persons (Merenlahti & Holoka 1999:38). The narrative worlds of the gospels are related in various ways to both the world of Jesus and the social world of the evangelist (Culpepper 1984:472). I read the story of Jesus not as a pure textual world, but as a text in the world. An actual author is communicating with actual readers within their concrete situation (cf. Luz 2007:15; Stock 1994:2).

2 . Genette (1980) defines the difference between a 'story' and a 'plot' in Discours du récit. The 'story' (histoire) refers to the chronological sequence of events, and 'plot' to the way these events are presented in the narrative. When the events selected from the lives of people of certain times and places are combined into a series in relation to one another, a plot develops and the story becomes a narrative discourse (récit).

3 . A character is a paradigm of constructed traits that a reader attaches to a name (Burnett 1993:16; Powell 2009:49).

4 . Greimas (1983[1966]:174-185; 192-212) defines the actants in narrative texts who fulfil actantial roles, for example the protagonist as the principle character or subject, the supporters (helpers) who assist the protagonist, the object(s) as the persons at whom the acts and values of the protagonist are directed, and the antagonists (opponents) as those who oppose the efforts of the protagonist (like the Pharisees and scribes) in the gospels. The plot develops as a result of the interrelation of such characters.

5 . With regard to this literary relation between the Synoptic Gospels, the Two-Source Hypothesis is taken as point of departure. It is therefore assumed that Mark was written first and was used by Matthew and Luke (De Silva 2004:166).

6 . The unusual word order 'Τοῦ δὲ Ἰησοῦ χριστοῦ ἡ γένεσις οὕτως ἦν' [But of Jesus Christ the origin was as follows] of Matthew 1:18a with which this short narrative is introduced, links it with the concluding words of the genealogy, 'ἕως τοῦ χριστοῦ γενεαὶ δεκατέσσαρες' [until the birth of Christ fourteen (generations)] in Matthew 1:17c. The repetition of the lexeme, 'γενέσεως' [of the genesis] (Mt 1:1) emphasises this and serves the same purpose.

7 . Based on the fact that no article is used with the Holy Spirit (ἐκ πνεύματος ἁγίου) in Matthew 1:18 and 21, which is different from Matthew 28:19 (τοῦ ἁγίου πνεύματος), some scholars contend that in Matthew 1:18-25 the author does not refer to the Spirit as Person, but rather as God's divine power and energy (cf. Davies & Allison 2004a:208). However, such interpretation remains speculative and less convincing.

8 . The phrase 'The young woman (almah) will conceive and give birth to a son, and will call him Immanuel' (Is 7:14) was originally addressed to King Ahaz of Judah when they were threatened by Syria and Israel to the North. The prophet assures the king that their plans to conquer Judah will not succeed.

9 . Births without the participation of a human father also appear in Hellenistic and Egyptian reports of the divine births of kings, heroes and philosophers (Luz 2007:92). A Jewish legend mentions the virginal birth of Melchizedek (2 Enoch 71:1-23).

10 . 'If a man said, "This is my son", he may be believed' (Mishnah, Baba Batra, 8.6).

11 . As mentioned earlier, some scholars contend that Matthew here does not think of the Spirit as Person, but rather as the divine power and energy of God. While Mark and Luke do use the article, which would indicate that they are thinking of the Spirit as Person, it is quite unlikely that Matthew would differ from their view.

12 . Topica (Topics of argumentation) is a rhetorical writing of Marcus Tullius Cicero, dated 44 BC.

13 . The Syrian Neoplatonistic philosoper Lamblichus (c. AD 245-c. 325) was the biographer of Pythagoras, the Greek mystic, philosopher and mathematician.

14 . The Proto-evangelium of James (c.a. AD 145) is an apocryphal gospel that reaches back in time to the infancy stories contained in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. In chapter 9, Joseph receives direction from an angel that he has been selected to become Mary's husband.

15 . Gerhardsson (1966) proposes that Matthew 4:1-11 is a haggadic midrash on the Shema (Dt 6:4-5), akin to a rabbinic disputation. Keeping the Shema implies acting like Jesus acted in the wilderness.

16 . In a certain sense, Jesus had already been tempted by John the Baptist who tried to prevent Jesus from being baptised.

17 . Matthew's order of Jesus's temptations reflects Israel's experience in the wilderness as narrated in Exodus. Because of their hunger, Israel doubted God (Ex 16); they tested God (Ex 17) and they forsook God and succumbed to idolatry (Ex 32).

18 . As Satan puts Jesus to the test three times, the religious leaders would also repeatedly put Jesus to the test. As Jesus had the last word with Satan so that he leaves, so Jesus had the last word with the religious leaders and they leave the scene (Mt 22:46-23:1). As Jesus will ultimately beat Satan in conflict, he beats the leaders in conflict.

19 . In the ancient Mediterranean world, healing involved more than physical healing from a disease. Healing implied the restoration of the total well-being of a person (Pilch 1988:60-66). This includes the restoration of meaning of life and honour. A healed person can again fully participate in societal activities. An ill person is a socially disvalued person. Restoring the meaning of life for an ill person, implies healing.

20 . Apart from Matthew 12:18, the Christological 'παῖς' of God only appears in Acts 3:13, 26; 4:25, 27.

21 . Isaiah 42:1-4 does not speak of Israel's deliverance from Gentile oppression, but of the Gentile's own salvation. The servant in Isaiah 42 is the solution to the plight of the Gentile world (Is 41:21-29; Chamblin 2010:655).

22 . The gospel begins the genealogy of Jesus with the unusual inclusion of the names of Gentile women (Mt 1); the veneration of the baby Jesus by the magi from the East in contrast to the animosity of Herod and the Jewish religious leaders (Mt 2); and the child murder and flight from Bethlehem to a safe haven in Egypt (Mt 2). While the animosity of the Jews against Jesus increases, the Canaanite woman recognises Jesus as the Lord (Mt 15). The scribes and Pharisees reject Jesus and Jesus delivers the condemnation of the scribes, Pharisees and Jerusalem when he says: 'Therefore I tell you that the kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a people who will produce its fruit' (Mt 21:43). The Roman officer and soldiers confess: 'Surely he was the Son of God' (Mt 27:54). The gospel concludes with the calling of the community to spread the teaching of Jesus to all nations (Mt 28:19-20),

23 . Contrary to the 'hypocrites' in Matthew 6:5, Jesus does not seek public acclaim.