Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

In die Skriflig

On-line version ISSN 2305-0853

Print version ISSN 1018-6441

In Skriflig (Online) vol.50 n.1 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/ids.v50i1.1972

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

African biblical studies: Illusions, realities and challenges

David T. Adamo

Department of Biblical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

African Biblical Studies is a biblical interpretation for the purpose of transformation in Africa. It is the biblical interpretation that makes the 'African social cultural context a subject of interpretation'. It is also the rereading of the Christian Scripture in a premeditatedly Africentric perspective. It means that biblical interpretation is done from the perspective of the African worldview. The purpose of this article is to discuss some illusions or misunderstandings, realities and challenges facing African biblical studies. Some of these illusions are that African Biblical Studies is fetish, syncretistic and primitive, local and not popular or universal. The basic distinctive realities and challenges facing African Biblical Studies are also critically discussed for the purpose of understanding what African Biblical Studies is and to make African Christianity more authentic in Africa.

Introduction

It is important to discuss my understanding of African in this article. The word African is used in a broad sense. In this article it is used to refer not only to the people in the continent of Africa geographically and the people of black colour but also to embrace people of African descent all over the world and those who embrace the African culture, religion and traditions (Adamo 2001b). In other words, I extend the boundary of Africa beyond the continent to include all the people of African descents all over the world.1

What is implied by African Biblical Studies? African Biblical Studies is the interpretation of the Bible for transformation in Africa. When we discuss the hermeneutic(s) that can transform Africa we are discussing the biblical studies that are vital to the well-being of our society. This can be called African cultural hermeneutics.2 African Biblical Studies is the biblical interpretation that makes 'African social cultural context a subject of interpretation' (Adamo 1999:60-90; 2001b; Ukpong 2002:17-32). It is the rereading of the Christian Scripture from a premeditatedly Africentric perspective. Specifically, it means that the analysis of the biblical text is done from the perspective of African worldview and culture (Adamo 2001b:6). African cultural hermeneutics or African Biblical Studies has three main characteristics: It is 'liberational, transformational and culturally sensitive'. It also has some other methodological characteristics such as narration, oral presentation, theopoetic and imagination. What it does is that it uses liberation as a crucial hermeneutics and mobilises indigenous cultural materials for theological enterprises (Sugirtharajah 1999:11). African Biblical Studies is 'postmodern, postcolonial in its aim to celebrate the local', and to challenge the reigning imported Western theories (1999:11).3Certainly African Biblical Studies has come of age, yet it has not been universally accepted. The purpose of this article is to discuss critically what I consider some illusions, realities and challenges of African Biblical Studies. It does not advocate a replacement of Western methods with African Biblical Studies without interaction or cross-fertilisation as some may misunderstand the purpose of this article.4

Illusions about African Biblical studies

In the course of trying to discuss and make clear what I mean by African Biblical Studies in several conferences, particularly in Nigeria, South Africa and the United States of America, there has been an accusation that some of us call African Biblical Studies an illusion. What they called illusions has been that it is formulated and made use of African indigenous materials and methods of African traditional religion and culture (Asaju 2005:121-129; Enuwosa 2005:130-136). Therefore, African Biblical Studies has been labelled as fetish, syncretistic and a return to African indigenous religious traditions. Is African Biblical Studies actually fetish, syncretistic and a return to African religious tradition?

Fetish, syncretistic and a return to African traditional religious tradition

In African indigenous society the belief in enemies as the main sources of all evil and occurrences is so strong that nothing happens naturally without a spirit force behind it. Thus, incidents like barrenness, infant mortality, accidents and other evil things are caused by enemies. Before the advent of Christianity, Africans had a cultural way of dealing with the problem of enemies and all evil ones. There are various techniques of making use of natural materials and potent powerful words that they put into defensive and offensive use dealing with evil ones. One of the cultural ways of protecting against enemies is the use of imprecatory spoken words (ogede in Yoruba language of Nigeria-incantation). In African indigenous tradition when an enemy is identified and one does not have the potent words or charms to deal with it, such a person consults a medicine person (babalawo in Yoruba language) who prepares a charm or potent words for such a person. A perfect example of such potent words used among the Yoruba people to make a sorcerer who are considered to be desperately wicked, lose his or her senses is:

Igbagbe so orokolewe (3 times)

Igbagbe se afomokolegbo (3 times)

Igbagbe so Olodumarekoranti la esepepeye (3 times)

Nijotipepeyebadaranegbaigbehohoniimubo 'nu

Ki igbagbe se lagbajaomolagbajakomaawogbo lo

Nitorit'todo ban san kiwoehin moo

Due to forgetfulness the oro (cactus) plant has no leaves (3 times)

Due to forgetfulness the afomo (mistletoes) plant has no roots (3 times)

Due to forgetfulness, god did not remember to separate the toes of the duck (3 times)

When the duck is beaten it cries, hoho

May forgetfulness come upon (name the enemy), the son/daughter of

(name the mother)

That is, may he/she loose his/her senses

That he/she may enter into the bush forever

Because a flowing river does not flow backward and so on.

The above potent words5 can be repeated two or three times to fight enemies.

Another way of dealing with enemies for protection is the use of charms or amulets which can also be possessed from the babalawo oronisegun [priests or medicine maker]. Charms are rapped with animal skin or cloths. Others may use a combination of potent words, charms and amulets for effectiveness. However, during the advent of Christian missionaries all these were forbidden and they were forsaken. Converts to Christianity who threw all these cultural ways of defending themselves were ridiculed, because the type of Western Christianity brought by missionaries did not provide substitutes for protection except prayers. In fact, and at a point, the Yoruba people of Nigeria called the Christian converts to Christianity who did not equip themselves with amulets, potent words and charms against enemies: women. Yoruba non-converts see Christianity as an impotent religion. Therefore, they began to look for substitutes to fight enemies and to cure diseases and bring success. Most unfortunate, the Western missionaries did not reveal to African converts the secret of their power and knowledge, but instead revealed prejudice and oppression. To summarise: the type of Christianity introduced to African converts did not meet the present needs of Africans - protection, healing and success. The African Christian converts began to suspect that the missionaries deliberately refused to reveal their source of power. African Christians therefore sought vigorously for the source of power which the Western missionaries refuse to introduce to them in the Bible - the Word of God. They found out later that there must be a secret power in the Bible when they read of the miraculous healings and the imprecatory psalms. They started using the so-called imprecatory psalms (e.g. Psalms 35 and 109) for protection against enemies, because they believe that it is as powerful as their potent words (ogede), charms and talisman. Psalms such as 5, 6, 28, 35, 37, 54, 55, 83 and 109 are classified as protective psalms which can be read and chanted, sung several times as the African so-called incantations (Adamo 2005:17-21; Ademiluka 1991:30; Bolarinwa n.d:8; Ogunfuye n.d:37). An example of these psalms mostly used, is Psalms 5:10:

Make them bear their guilt O God

Let them fall by their own counsels

Because of their many transgressions

… All my enemies shall be ashamed

And sorely troubled, they shall turn

Back and be put to shame in a moment (RSV).

Psalm 55:15, 23 says:

Let death come upon them;

Let them go down to sheol alive

Let them go away in terror into their grave

(they shall not live out half their days) (RSV).

Psalms 91:5-10 is another example of biblical passages used for protection, healing and success:

Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night; nor for the arrow that flieth by day; Nor for the pestilence that walketh in darkness; nor for the destruction that wasteth at noonday. A thousand shall fall at their side, and ten thousand at the right hand; but it shall not come nigh thee. Only with thine eyes shalt thou behold and see the reward of the wicked. … There shall no evil befall thee, neither shall any plague come nigh thy dwelling.

African Biblical Studies has been labelled 'a return to African indigenous religion' (Asaju 2005:121-129).6 Admittedly a casual look at African Biblical Studies urges the temptation to condemn the Africentric7 interpretation or African Biblical Studies as fetishist, syncretistic, magical, unchristian and uncritical. The reason for this is because the ways of dealing with enemies in African indigenous religion is transferred to African Christianity. This is what is called contextualisation and African biblical herneneutics.8 Indigenous Africans have ways of protecting themselves from enemies.

However, a closer and critical examination of African Biblical Studies will reveal some facts that make it legitimate, important, and Christian. The use of imprecatory psalms with the names of God shows the recognition of the power in names within African tradition that is quite similar to the power attributed to names in the Hebrew Bible. African Christians revere the names of God and believe that these names in the Bible are powerful when recited. The recitation of such names will achieve whatever result is desired. The use of the imprecatory psalms for protection against enemies and evil spirits is based on the recognition of a fundamental belief in the power of words. The belief in the potency of words within African tradition, especially among the Yoruba of Nigeria, is transferred to the belief in the power in the words of God in Scripture when they are memorised, recited, sung, and read (Heb 4:12).

The efficacy of this practice is never doubted among African Christians and most churches in Africa. I am strongly convinced that it is better for African Christians to read the imprecatory psalms than going to native priests for harmful medicine to destroy their enemies.9 This belief is still very strong even among the westernised Yoruba people of Nigeria. Ogunkunle (2000), for example states:

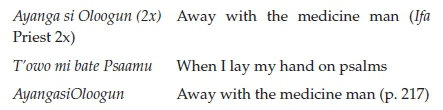

The book of Psalms became the most favourite books of the Bible believed to be more powerful than any other books. They used it for protection, healing, and success. This can be illustrated by the following popular song in the early days of African Indigenous Churches (p. 217):

A song similar to the one just mentioned calls for the use of the psalms incantations against evil (cf. Oshitelu n.d.:14):

I challenge the juju men, once I lay hold on my Psalms

Praying with Psalm is a staff of victory

Praying with Psalm is a great protection

Praying with Psalm is a staff of provision

Praying with Psalm is a virtue of healing

Praying with Psalm is a staff of peace.

Here are a few further examples of the use of Psalm 109 as protection and defence within African Christianity in Nigeria. When one looks at the use of a specific psalm as an incantation it is sensible to argue that, within the Anglican Church in Nigeria, Psalm 109 is used for God to bring vengeance on one's enemies and for deliverance. Bolarinwa (n.d.:55), the former registrar of the Anglican Diocese of Ibadan, for example illustrates how each chapter of the book of Psalms can be used as potent words for deliverance, protection, healing and success in life. Accepting the authorship of David, he (n.d.:55) proposes to read Psalm 109 generally as a daily prayer for three consecutive days in order to wreak vengeance on those who are unreasonably hostile to someone. Currently many Anglican Church members and leaders read Psalm 109 in this way. In fact, they would sometimes go secretly to the prophets and pastors of the Aladura churches who specialise in using psalms as incantations.

However, there is a temptation for scholars, especially Western scholars, to dismiss the Africentric interpretation as fetish and unscholarly (Asaju 2005:121-129; Enuwosa 2005:130-136), but a closer examination of the interpretation shows that care must be taken before the condemnation of such practice. It is likely that ancient Israelites used the book of Psalms for protection, for healing and success according to the culture of the ancient Near East (Shmitz 2002:817-822; Smoak 2010:421-432; 2011:75-92). There is the likelihood that it was the way ancient Israel actually interpreted and used the words of psalms in their worship as supported by archaeological discovery discussed below.

The existence of a handful of Phoenician and Punic amulets from the first millennium with the same verbs, guard (smr) and protect(nsr), inscribed on their surfaces supports this view (Schmitz 2002:817-822; Smoak 2010:12, 421-432; 2011:75-92). The presence of these two verbs in both West Semitic inscriptions and the book of Psalms show some common cultural and religious practices and common purpose for invoking the deity's protection or help in prayer and amulet inscriptions (Smoak 2011:75-92). Inscribing words in metal and apotropaic magic in ancient Israel is not uncommon as uncovered by archaeologists (Smoak 2011:75-92). Several 7th to 6th century Punic gold bands were discovered in the excavations at Carthage with inscription of the same two verbs as part of a protective formula like that of the psalms (Krahmalkov 2000:471-472; Mendelssohn & Barnett 1987).10

It is certain that the culture of ancient Near East makes one believe that the words of the Psalter were memorised and recited not for fun or aesthetic or scholarly purposes, but with faith behind the recitation, singing or chanting of the psalms, and with the expectation that they would achieve a desired effect. In ancient Israel these words were believed to be potent and performative words that sought to invoke a particular result. Like the ancient Israelites who were the original authors of the Psalter, many African biblical scholars see the Psalter as divine, potent and performative. It can be used to protect one from enemies, or it can heal diseases and bring about success. A few eminent biblical scholars such as R. Bultmann, W. Eichrodt, E. Jacob, G.A.F. Knight, O. Procksch and G. von Rad, agreed that the spoken word in ancient Israel was 'never an empty sound but an operative reality whose action cannot be hindered once it has been pronounced' (Bultmann 1969; Eichrodt 1967; Jacob 1958; Knight 1953; Procksch 1967; Thielton 1974; Von Rad1965).

The above shows that African Biblical Studies is neither fetish, syncretistic, nor a return to African traditional religious tradition. It only made use of the local or indigenous materials and methods in the interpretation of the Bible. It is not therefore a return to African religious tradition, because the way it made use of such tradition and method is not alien to the culture of the Bible and the ancient Near East.11

Local

Another illusion is that African Biblical Studies has been labelled as too local and primitive and that is why it is not globalised. I think that such illusion is due to the extent of exposure and lack of the knowledge of what exactly African biblical scholars are doing with African Biblical Studies. African Biblical Studies uses the mode of interpretation that 'seeks to acquire and celebrate their God-giving identity by delving into their indigenous resources and rejecting the superintending tendencies of Western intellectual tradition' (Sugirtharajah 1999:11). They address issues closer to home to their own people (1999:12-13). What they did was that they 'learnt and borrowed ideas and techniques from external resources but reshaped them, often added their own indigenous texture, to meet their local needs' (1999:60-90). Masenya (2012:283-298) is an example of those who did this perfectly well. She calls on both Badimo[ancestors] and Modimo [God] and draws from the Northern Sotho storytelling traditions, proverbial philosophies and sayings and worldview to read the book of Job. She also used many Sotho-Pedi words and phrases, sayings and proverbs to show to the reader that she reads and writes from another centre and worldview than the Greek and Hebrew worldview.

Unlike the Western claim, African Biblical Studies does not claim 100% objectivity. This is because a casual glance at the history of biblical studies reveals that there has never been an interpretation interpretation without references or dependent on a particular cultural code, thought patterns, or social location of the interpreter (Adamo 2005:17-31; 2008:575-592; Mulrain 1999:116-132). There are no individuals who are completely detached from everything in their environment or experience and culture so as to be able to render 100% objectivity in every interpretation. The fact is that every interpreter is biased in some ways (Adamo 2008:575-592). What I am trying to say is that there is what we may call African Biblical Studies or African biblical transformational studies because persons who are born and raised in Africa will normally interpret Scriptures in ways that are unique to them and different from Western interpreters. Therefore, to talk of uniform, unconditional, universal, and absolute interpretation or studies is unrealistic. Such does not exist anywhere in this world. They who interpret tend to bring their own bias to bear, consciously or unconsciously, on the way in which the message is perceived.

I can confidently tell my readers that African Biblical Studies is globalised. Every year African Biblical Studies has several sessions during the meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature. The latter is the most important and prestigious academic religious organisation in the world and was established in 1879 and has an international meeting every year all over the world. However, it does not mean that the discussion at this meeting (SBL) are whole heartedly acceptable universally by other mainline Western scholars. There is still a need to formulate and reformulate African Biblical Studies in different versions until it is universally acceptable. Admittedly, no specific interpretation can be acceptable by the whole world because other people's views should be respected as this writer does for Western scholarship even though all of it is not acceptable.

Eurocentric universality

The eurocentric interpreters' claim to universality is another illusion. According to many of the Euro-American interpreters there is still a claim that the only legitimate, authentic and recognised mode of interpretation is the Western mode of interpretation. Shohat and Stam (1994) highlighted the ideological conditioning that Africans and the black race have been subjected to by saying:

Eurocentric discourse thoroughly informed academic paradigms by situating the West (Europe, North America) as the center of knowledge production to maintain the ideology of superiority and the suppression of the other. (p. 15)

'This eurocentric ideology presented Western history, philosophy, theories, methods, texts, stories, culture and structures as the epitome of knowledge production and all that is best' (Shobat & Stam 1994:2-3).

African Biblical Studies supports the principle of interpretation of the Bible for transformation in Africa. The eurocentric method of interpretation is the interpretation in history which includes allegorical method, literal method, source criticism, historical criticism, form criticism, tradition-oral criticism, textual criticism, structural criticism, social criticism, rhetorical criticism, canonical criticism and other criticism. Though all these methods mentioned above are honest attempts by eurocentric scholars to understand the Bible in their eurocentric worldview or culture, they do not adequately meet the need of the African people. These eurocentric studies have not addressed the abject poverty prevalent among the African people. It has not addressed the oppression and the pain of witches and wizards which is very real among the African people. Such studies have not addressed adequately the problems of African ancestors and the question of land domination in the African continent. African culture and religion are not taken seriously in the eurocentric studies. Any brand of Christianity and scholarship, which does not take seriously the African life situation, is irrelevant to African people and African Christianity. This is because Africans have experiences different from the eurocentric worldview. Africans need to use their genius to redefine their own peculiar studies with a task of interpreting the Bible in their own ways. When we discuss the studies that can transform Africa we are discussing the biblical studies that are vital to the well-being of our society. This is African Biblical Studies or African biblical transformational studies.12 We are discussing the very studies that can change the poverty level of African people and deliver one from the oppression of witches, wizards, sickness, the colonial mentality of Africans and all forms of oppressions.

African Biblical Studies is the biblical interpretation that makes the 'African social cultural context a subject of interpretation' (Adamo1999:60-90; 2001b; Ukpong 2002:17-32). This is the study that reappraises ancient biblical traditions and African worldview, culture, and life experience with the purpose of 'correcting the effect of the cultural ideological conditioning to which Africa and Africans have been subjected in the business of biblical interpretation' (Adamo 2001b). Many African people have been told they have no contribution to world civilisation (Fage 1970:20; Wilks 1970:7). They have been subjected to the belief that African people or the black race has nothing to offer or contribute to the development of humanity as far as historical evolution of biblical studies is concerned (Fage 1970:7-10; Wilks 1970:7). Unfortunately, whenever we submit academic articles that reflect the methodology of African Biblical Studies, our articles are dismissed as fetish, magical, barbarous and unscholarly (Enuwosa 2005:130-136). An example of this is when I sent several articles to some Western journals for publication and I was accused of trying to smuggle Africa and Africans to the Bible. I have also been told that Egypt is never part of Africa ethnically and therefore ancient Egyptians were not part of black Africa. The theory that Africans have not participated in the biblical drama of redemption despite so many presence and the contribution of African ancestors in the Bible is another example of this ideological conditioning.13 African Biblical Studies is the rereading of the Christian scripture from a premeditatedly Africentric perspective. It is contextual since interpretation is always done in a particular context. Specifically it means that the analysis of the biblical text is done from the perspective of the African worldview and culture (Adamo 2001b:6).14

The purpose is not only to understand the Bible and God in African experience and culture, but also 'to break the hegemony and ideological stranglehold that eurocentric biblical scholars have long enjoyed' (Adamo 2001b; Yorke 1995:145-158).

African cultural studies or African Biblical Studies has three main characteristics: It is 'liberational, transformational and culturally sensitive'. Musa Dube (2012:29-42) reported an example of studies that is liberational, transformational and culturally sensitive adopted by Kimpa Vita (1684-1706), a former indigenous doctor, (nganga), who tried to decolonise the gospel by contextualising biblical places to her land and saw biblical characters as black. Even though she was 20 years old, she preached an outright rejection of colonising Christian symbols and insisting that God shall restore the colonially disgraced land of Congo (Dube 2012:29-42). What it does is that it uses liberation as crucial studies and mobilises indigenous cultural materials for theological enterprises (Sugirtharajah1999:11).

African Biblical Studies also has some other methodological characteristics such as narration, oral presentation, and theopoetic. By narration we mean an approach that sees the Bible as a storybook and then interprets those stories as divine stories. Perhaps this can also be called storytelling studies. By the theopoetic characteristic of African Biblical Studies I mean the art of reading and interpreting religion poetically (Adamo 2001b:45-76). This may involve all kinds of melody such as chanting, singing, dancing in the form of music. Specifically this is chanting and singing the Scripture as the Word of God. This is called the songs of God or songs to God (2001b:45-76). The orally characteristic of African Biblical Studies is the reading and interpreting of a religious text orally. There is need for serious memorisation of oral tradition as passed on from generation to generation.

Realities of African Biblical studies

By realities in African Biblical Studies I mean some of the important or essential elements or qualities of African Biblical Studies. Perhaps I can call it that what makes African Biblical Studies to be distinctive from other biblical studies. Some of this distinctiveness are realities and have not been fully discussed and acceptable by not only Euro-American scholars but also African scholars. It means that there is a need to state it and continue to discuss it because many African biblical scholars who are committed to African Biblical Studies (West, Maluleke, Masenya, and Mosala) have not exhausted all these distinctive realities in African Biblical Studies.15 These can be referred to as follows: African communality, African presence in the Bible, blackening the Bible, African comparative studies, Bible as power, Africa as a means to interpret the Bible, African distinctive interest, and African identity. Details of these essential elements are discussed below.

Communal reading

One of the main elements of African biblical interpretation is the communal reading. This has been referred to in various ways such as 'reading with the Ordinary readers', 'reading with the community', 'reading with African eyes', reading with 'residual illiterate people', 'real contextual readers', 'spontaneous and sub-conscious readers', 'collaborative and interactive' readers. According to West (2009:21-41), ordinary readers are ordinary people, the poor and the marginalised communities. According to Draper (1996:59-77) they are those who are working with residual oral culture who employ residual oral hermeneutic in their readings. The ordinary readers are also identified as 'real contextual readers'. These ordinary readers are also identified as spontaneous and sub-conscious readers because they read subconsciously and spontaneously for direct use in their social location. Eric Anum (2009:143-165) calls their reading 'collaborative and interactive hermeneutic'. Ukpong (1995:3-14) gave a common element in African worldviews and culture, that is, the sense of a community (cf. Adamo 2001a). West also discusses this type of reading as 'Reading otherwise'. Jonker (2001:78-88) advocated for a communal approach to the reading and interpretation of the Bible and listed many benefits of it.

After all, the Bible is a community document. According to Riches (1996:181-188), both ordinary and scholarly readers belong to 'a community of readers'. The fact is that ordinary Africans and non-scholarly interpreters are constitutive of our scholarship in ways that I think is not the case in current Euro-American practice (Ukpong 2001:188-212; West 2002:65-94).

The Bible as power

An important distinctive development in African Biblical Studies is the use of the Bible as power. This is an existential and reflective approach to the interpretation of the Bible. Unlike the eurocentric conservative biblical scholars who were preoccupied with the subject of inerrancy and infallibility of the Bible, African Christians believe and respect the Bible without any attempt to defend it and apologise for it. The Bible is the Word of God and is powerful and its power is relevant to everyday life of Africans (Adamo 1999:60-90;2001a:7-39; 2003:9-33; 2012b:299-316; Nthaburi & Waruta 1997:40-57). That is why the Bible is used as a means of protection where the fear of witches and wizards is the order of the day. The power of the Bible is also used therapeutically for healing where there is prevalence of diseases without the means of access to the hospitals. The Bible is used as means of success where there is a prevalence of abject poverty. Although this practice is mostly in the African indigenous churches, it has spread to not only the Pentecostal churches but also the mission churches and the African diaspora. Many African scholars have made important investigations to the use of the Bible as power. Ademiluka (1991) wrote: 'The use of therapeutic Psalms in inculturating Christianity in Africa.' Adamo also made some important contributions in his books and articles on this line such as: 'The use of medicine in African indigenous churches in Nigeria' (Adamo 1997-1998:73-101); 'The distinctive use of Psalms in African independent churches in Nigeria' (Adamo 1993a:94-111), 'Reading and interpreting the Bible in African indigenous churches and others' (Adamo 2001d).

Africa and Africans' presence in the Bible

Another very important distinctive reality in African Biblical Studies is Africa and African presence in the Bible. Ukpong (2000:11-28) was emphatic that Africa and Africans in the Bible is a methodology which cannot be ignored. This method reaches its peak during the 1990s to the present. It discusses the presence and the contributions of Africa and Africans in the Bible. To my knowledge no biblical interpretation searches for the presence and the contribution of Africa and Africans in the Bible. Africa and Africans are mentioned, however, in every strand of biblical literature (Adamo 2006).16 African biblical scholars continue to use the methodology of Africa and Africans in the Bible and discovered that Africa and Africans were mentioned more than 1700 times in the Bible. The conclusion is that the Bible would have never been in the shape it is now without Africa and African participation in the drama of redemption. African biblical scholars continue to demonstrate the importance and influence of Africa and Africans in the Bible (Bailey 1991:165-186; Copher 1991:146-164; Felder 1991:127-145; Wimbush 2009:162-177).17 African biblical scholars also demonstrate that the Bible is not only an ancient Jewish document alone it is also an African document. Through this type of reading we find that there is no prejudice against Africa and Africans in the Bible. The present prejudice by some Western biblical interpreters is a modern invention because nowhere in the Bible the ancient Israelites were prejudice against any African because of their black skin.

Many African biblical scholars have made much progress. Teresa Okure's (1996) article, 'Africans in the Bible: A study of hermeneutics', and Adamo's book (2001b) have made some important contributions between the 1980s and 2014. The following writings of Adamo are worth mentioning: 'The African wife of Moses' (1989:230-237); 'Ancient Africa and Genesis 2:10-14' (1992a:33-43); 'Ethiopia in the Bible' (1992b:51-54); 'The table of nations in an African context' (1993b:2-15); 'In search of Africanness in the Bible' (2000:20-40); Africa and Africans in the Old Testament (2001a); 'The African wife of Abraham' (2005:455-471); 'Images of cush in the Old Testament: A reflection on African biblical hermeneutics' (2001b:65-74); Africa and Africans in the New Testament (2006); 'The African wife of Jeroboam' (2013a:71-89); 'The African wife of Joseph' (2013b:409-425), 'The nameless African wife of Potiphar and her contribution to ancient Israel' (2013c:221-246), 'The African queen and examination of 1 Kings 10:1-13' (2014a:1-20); and 'The African wife of Solomon' (2014b:1-20). Many African Americans are also pioneers in the field of using the methodology of Africa and Africans in the Bible. This involves finding Africa and Africans in the Bible and making it the basis for biblical interpretation (Ukpong 2000:11-32)

Very few eurocentric scholars have shown interest in researching on Africa and Africans in the Bible. A Norwegian scholar, Knut Holter, is exceptional because he has published many books and articles using Africa and Africans in the Bible. He wrote: 'Should Old Testament cush be rendered Africa?' (1997:333-336), and Yahweh in Africa (2000). He seems to be an outstanding Western African biblical scholar among Euro-Americans who is deeply interested in this area of using the methodology of Africa and Africans in the Bible (Holter 2000:569-581).

African comparative reading

Another important distinctiveness reality in African Biblical Studies is African comparative reading. Of course there are many types of comparative approaches to biblical studies. Many eurocentric interpreters are preoccupied with comparing the Bible with the so-called ancient Near East which they said includes Egypt. Yet when they do any comparison of the Bible with Egypt, they do that as if Egypt is an European country or as if it is not part of Africa. Ancient Israel ancestors once lived in Africa for about 430 years (Ex 12:41) and by the time they left Africa they were all African-Israelites. This was discussed in detail in (Adamo 2012a:67-78), 'A mixed multitude: Exodus 12:38 in African context'.18 This comparative approach is the comparison of the Bible text, religion and culture with African text, religion and culture. This comparison of Africa, the Bible and Christianity brings out the relevance of African culture to the study of the Old Testament and the Old Testament to Africa and Africans.

African evaluative approach

An important distinctiveness of African Biblical Studies is African evaluative approach (Adamo 2003:9-33). Evaluative approach has to do with African and non-African biblical scholars mostly specialising in their books or essays in criticising the works of African biblical scholars. This type of criticism may be constructive, negative or both. This criticism is only for progress, correction and readjustment in African Biblical Studies. There are some African biblical scholars who are good at this. Prof. Knut Holter and Marta Hoyland, both Norwegians, are at the forefront. Yahweh in Africa, which deals with such constructive criticism, is concerned with excellence in African Old Testament studies. Hoyland (1998:50-58) also decries the marginalisation of African Old Testament studies by Euro-American scholars and some African scholars themselves also criticises Adamo's interpretation of all cush passages as Africa (Holter 2000b:107-114; Hoyland 1998:50-58). Despite his criticism of Adamo's work he still rates it so far then as the most prolific and productive African Old Testament scholarly work. Despite his criticism and after evaluating four African Old Testament scholars, E. Mveng, G.A. Mikre-Selassie, Sempore and Marta Hoyland credited Adamo with the honour of 'probably being the African scholar who has made the single most important contribution to the field of African presence in the Old Testament' (Holter 2000:43-54). According to Hoyland though, Adamo has neglected the negative aspect of Africa in his work. These criticisms are valuable because they help us to know which areas to improve.

Using Africa to interpret the Bible

Using Africa to interpret the Bible is also a distinctive element in African Biblical Studies (Ukpong 2000:16-17). A combination of historical-critical method and anthropological or sociological methods are used. While the historical-critical method is used only to analyse the text, the anthropological or sociological method is used to analyse African culture and situation, or the purpose of understanding a particular biblical text in the light of African tradition and situation for the purpose of arriving at authentic Christianity that is both African and biblical (2000:16). An example of this type of research is E.A. McFall's (1970) Approaching the Nuer through the Old Testament and Using Nuer culture of Africa in understanding the Old Testament: Evaluation (Fiensy 1987:73-83).

Distinctive interest

Another distinctive element of African Biblical Studies is the type of interest that African biblical interpreters bring to the texts. According to West, there are two major interests that interpreters usually bring to the texts. Interpreters usually come to the text with what we may call interpretative interests and life interests (West 2009:37-64). The distinctive element of African biblical interpreters is that they bring life interests to the interpretation of the Bible while the Euro-American interpreters bring interpretative interest to the text. While interpretative interests refer to those dimension of the text that interest the interpreters, life interests are those concerns and commitments that drive or motivate the interpreters to come to the texts. In such a case such concerns and commitments shape the very questions that are brought to the biblical text (2009:37-64). This life interests may pertain to healing, protection and success in life. It may be religious, cultural and socio-political commitments. They may be race, class, or gender. Thus, when African biblical interpreters come to the Bible they want to know what the text has to offer concerning these things. However, the majority of Western biblical scholars come to the text with historical and social, literary dimension of the text (2009:37-64).

African identity

African Biblical Studies has African identity as its distinctive element. Ninian Smart (1969:12-25; 1973:42-43) identifies six different things that bring about identity, namely social institutions, ethical teachings, rituals, religious experiences, myths and doctrine. A casual look at the history of biblical interpretation reveals the act that no hermeneutic reveals the African identity like African Biblical Studies. As far as African and Christian identity is concerned several key concepts are important, viz. indigenisation, contextualisation, inculturation, Africanisation and a few others. All these concepts are utilised and are very important to African Biblical Studies (Conradie 2005:8). African identity is paramount in African Biblical Studies.

African Biblical Studies gives readers and interpreters the opportunity of self-awareness and self-identity. Interpreting with the poor brings the biblical interpreters to become aware of their own hidden preoccupations or antipathies during conversation. As the text is discussed African biblical scholars are aware of the fact that they have been colonised by Euro-American theories of biblical interpretation (Anum 2009:143-165).

Blackening the Bible

One of the realities of African Biblical Studies is the attempt to blacken the Bible in the process of interpretation. The blackening of the Bible is not limited to black colour. It includes African culture, religion all over the world and of course, the African continent. This blackening of the Bible is one of the distinctive aspects of African Biblical Studies. The blackening of the Bible means placing Africa and Africans at the centre of the biblical world and our biblical interpretation.19 This also means a vigorous attempt to use race, religion and culture as a tool for re-envisioning the landscape of the biblical world and interpretation. This is 'true Africentricism', that is, the idea of placing Africa as an ideological construct at the centre of biblical investigation that will serve as a useful tool for African scholars in our endeavour to create a hermeneutic that speaks to the needs of a historically marginalised people (Brown 2004:54).20 Many Africans and African Americans such as Charles Copher, Randall Bailey, Cain Hope Felder, Vincent Winbush, Madipoane Masenya, Musa W. Dube, Dora Mbuwayesango, Andrew Mbuvi, Gerald West, David Adamo, Knut Holter, and so many others who are engaged in African Biblical Studies are doing their best in blackening the Bible in their interpretation. In fact, one can say with great confidence that the people referred to as ancient Israelites were also Africans. That is why they are called African or Israelite because by the time they left Egypt or Africa after 430 years, having eaten African food, worn African clothes, danced African dances, spoken the African language, and immersed in African culture, it will be unrealistic for any scholar to deny the fact that they were African-Israelites (Adamo 2012a:67). It will also be unrealistic to deny that ancient Egyptian religion and culture are African culture and in fact, black culture (Adamo 2013b:409-425; 2013c:221-246). Budge, Rawlinson and Maspero were emphatic that the original home of the Egyptian ancestors was Punt which is to be sought in the African side of the gulf where the present side of Somaliland is located (Budge 1976 512-513; Maspero 1968:488; Rawlinson n.d:72). Budge (1976) says:

It is interesting to note that Egyptians themselves always appear to have had some idea that they were connected with the people of the land of Punt which they considered to be peopled by 'Nehesh', or 'Blacks', and some modern authorities have no hesitation in saying that the ancient Egyptians and the inhabitants of Punt belong to the same race. Now Punt is clearly the name of a portion of Africa which lay far to the south of Egypt, and at no great distance from the western coast of the Red Sea, and, as many Egyptians appear to have looked upon this country as their original home, it follows that, in the early period of dynastic history, at least, the relation between the black tribes of the south and the Egyptians in the north were of friendly character. (pp. 512-513)

Challenges

Despite all the globalisation, the importance of African Biblical Studies in maintaining our African identity is helping us to understand God in the ways he has revealed himself to us in combating our inferiority complex and the Western academic hegemony, and other important functions. How many of our higher institutions of higher learning in Africa, who are sensitive to this, include such studies in their biblical studies curriculum? Unfortunately there are very few according to my knowledge. I can only mention Delta State University, Kogi State University (where I have taught) and the University of Ibadan which have taken this seriously. Why is this? Is our culture not important? Is our ancestors' participation in the drama of redemption not important? I strongly believe that it is anathema to teach biblical studies exactly the way it is taught in Euro-American universities. Our teaching of biblical studies should reflect who and what we are. Perhaps my example of a curriculum of biblical studies in the higher institutions will explain this statement:

1. Africa and Africans in the biblical period.

2. The history of ancient Israel in African perspective.

3. Introduction to the Old Testament in African perspective.

4. Introduction to the New Testament in African perspective.

5. Theology of the Old Testament in African perspective.

6. Theology of the New Testament in African perspective.

7. African cultural hermeneutic(s).

8. Some specific books such as Psalms or the prophets can be studied in African perspective.

9. Archaeology of the Old Testament in African perspective.

10. Archaeology of the New Testament in African perspective.

Our churches should be a place to actually apply African Biblical Studies at the grassroots level. This should not be left only to African indigenous churches which are at the forefront of doing African Biblical Studies. The mainline missionary churches should get themselves involved so that their churches will not be alien to the African community. In doing this they will reduce their members migrating to the African indigenous churches.

Conclusion

In African Biblical Studies, God is not considered a one-way track God. His mode of revelation to the world cannot be limited. The real issue in African Biblical Studies is therefore to use our finite human knowledge, experience and communication to speak about God who is all embracing. The fact is that no one has yet been able to invent such language to encapsulate God's completeness (Mulrain1999:117-121). It looks like an impossible task, but we must keep on trying. Who knows? God may have mercy on us by granting such absolute knowledge one day.

The distinctive elements of African Biblical Studies are reading with the community, the Bible as power, the African comparative approach, and the evaluative approach, using Africa to interpret the Bible, the approach of African and Africans in the Bible and blackening the Bible. The above indicate that the future of African biblical scholars is bright and the struggle to fulfil the task and the distinctiveness must continue.

This study should forge ahead because it will be difficult to make Christianity and the interpretation of the Scripture relevant to the people of Africa. Scholars of African descent are particularly challenged to pursue this study aggressively whether it is accepted by the mainline Western scholars or not. It must also be stated that African Biblical Studies does not reject other methodologies that may be useful for the purpose of interpreting the Scripture in African context because there must be a cross-fertilisation to enrich one another.

The temptation for a non-African biblical scholar when reading this article is to think that the purpose of African Biblical Studies is to advocate a displacement or a dismissal of the eurocentric approach. The purpose of this article is not to condemn or say that the distinctive elements of African Biblical Studies are the only legitimate and universal approach, but that is but one of the legitimate methodologies. As said above it is not in isolation because it interacts and builds on other approaches to a certain extent. The distinctive elements discussed above attempt to decolonise the interpretation of the Bible in the light of African culture and tradition.

Finally, it is recommended that every higher education in Africa with a Department of Religion should consider very seriously the outlined curriculum above in their attempt to make the teaching of the Bible more authentically African and to promote the African identity.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Adamo, D.T., 1989, 'The African wife of Moses: An examination of Numbers 12:1-9', African Theological Journal (ATJ) 8(3), 230-237. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 1992a, 'Ancient Africa and Genesis 2:10-14', Journal of Religious Thought 47(1), 33-43. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 1992b, 'Ethiopia in the Bible', African Christian Studies 8(2), 51-54. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 1993a, 'The distinctive use of psalms in African independent churches in Nigeria', Melanesian Journal of Theology 9(2), 94-111. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 1993b, 'The table of nations in an African context', Journal of African Religion and Philosophy (JARP) 2(2), 2-15. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 1997-1998, 'The use of African indigenous medicine in African indigenous churches in Nigeria', Bulletin of the International Committee on Urgent Anthropological and Ethnological Research 39, 73-101. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 1999, 'African cultural hermeneutics', in R.S. Sugirtharajah (ed.), Vernacular hermeneutics, pp. 60-90, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2000, 'In search of Africanness in the Bible', Nigerian Journal of Biblical Studies 15(2), 20-40. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2001a, Africa and the Africans in the Old Testament, Wipf & Stock, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2001b, 'African background of African American liberative hermeneutics' in D.T. Adamo, Explorantion in African Biblical Studies, pp. 3-28, Wipf & Stock, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2001c, Explorations in African Biblical Studies, Wipf & Stock, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2001d, Reading and interpreting the Bible in African indigenous churches, Wipf & Stock, Eugene, OR. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2003, 'The historical development of Old Testament interpretation in Africa', Old Testament Essays 16(1), 9-33. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2005, 'What is African Biblical Studies?', in S.O. Abogunrin (ed.), Decolonization of biblical interpretation in Africa, pp. 17-31, Nigerian Association for Biblical Studies, Ibadan. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2006, Africa and Africans in the New Testament, University Press of America, Lanham, MD. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2008, 'Reading Psalm 109 in African Christianity', Old Testament Essays 21(3), 575-592. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2012a, 'A mixed multitude: An African reading of Exodus 12:38' in G. Yee & A. Brenner (eds.), Exodus and Deuteronomy, pp. 67-78, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2012b, 'Decolonizing the Psalter', in M. Dube, A. Mbuvi, & D. Mbuwayesango (eds.), Postcolonial perspectives in African biblical interpretations, pp. 299-316, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2013a, 'The African wife of Jeroboam (Ano?): An African reading of 1 King 14', Theologia Viatorum 37(2), 71-89. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2013b, 'The African wife of Joseph', Journal for Semitics 22(2), 409-425. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2013c, 'The nameless African wife of Potiphar and her contribution to ancient Israel', Old Testament Essays 26(2), 221-246. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2014a, 'The African queen and examination of 1 Kings 10:1-13' (2014:1-20). [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T., 2014b, 'The African wife of Solomon', Journal of Semitics 23(1), 2-20. [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T. & Eghwubare, F., 2005, 'The African wife of Abraham', Old Testament Essays 18(3), 455-447. [ Links ]

Ademiluka, S., 1991, 'The use of psalms in African context', MA dissertation, Faculty of Arts, University of Ilorin, Ilorin. [ Links ]

Anum, E., 2009, 'Collaborative and interactive hermeneutics in Africa: Giving dialogical privilege biblical interpretation', in H. de Wit & G.O. West (eds.), African and European readers of the Bible in dialogue, pp. 143-165, Cluster Publication, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Asaju, D.F., 2005, 'Afro-centric biblical studies: Another recolonisation', in S.O. Abogunrin (ed.), Decolonization of biblical interpretation in Africa, pp. 120-129, Nigerian Association for Biblical Studies, Ibadan. [ Links ]

Bailey, R.B., 1991, 'Beyond identification: The use of Africans in the Old Testament poetry and narratives', in C.H. Felder (ed.), Stony the road we trod, pp. 165-186, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Bolarinwa, J.A., n.d., Potency and efficacy of psalms, Olusevi Press, Ibadan. [ Links ]

Brown, M.J., 2004, Blackening of the Bible: Aims of African American biblical scholarship, Trinity Press International, Harrisburg, PA. [ Links ]

Budge, W., 1976, Egyptian Sudan, vol. 1, Arno Press, New York. [ Links ]

Bultmann, R., 1969, 'The concept of the Word of God in the New Testament', in R. Bultman (ed.), Faith and understanding, pp. 287-297, Charles Scribner, London. [ Links ]

Conradie, E., 2005, Christian identity: An introduction, Sun Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Copher, C., 1991, 'Black presence in the Old Testament', in C.H. Felder (ed.), Stony the road we trod: African American biblical interpretation, pp. 146-164, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Draper, J., 1996, 'Confessional western text-centered biblical interpretation and oral residual text', Semeia 73, 59-77. [ Links ]

Dube, M., 2012,'Talitha cum hermeneutic of liberation: Some African women's ways of reading the Bible', in M. Dube, A.M. Mbuvi, & D.R. Mbuwayesango (eds.), Postcolonial perspectives in African biblical interpretations postcolonial, pp. 29-42, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Eichrodt, W., 1967, Theology of the Old Testament, vol. 2, Westminster, Philadelphia, PA. [ Links ]

Enuwosa, J., 2005, 'The prospect of decolonizing biblical studies in Nigeria', in S.O. Abogunrin (ed.), 'Decolonization of biblical interpretation in Africa', pp. 130-136, Nigerian Association for Biblical Studies, Ibadan. [ Links ]

Fage, F.D, (ed.), 1970, Africa discover her past, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Felder, C., 1991, 'Race, and biblical narratives', in C.H. Felder (ed.), Stony the road we trod, pp. 127-145, Fortress, Minneapolis, MN. [ Links ]

Fiensy, D., 1987, 'Nuer culture of Africa in understanding the Old Testament: Evaluation', Journal for the Study of Old Testament 38(1), 73-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030908928701203806 [ Links ]

Holter, K., 1997, 'Should Old Testament cush be rendered African?', The Bible Translator 48(3):331-336. [ Links ]

Holter, K., 2000a, Yahweh in Africa, Peter Lang, New York. [ Links ]

Holter, K., 2000b, 'Africa in the Old Testament', in G. West &M. Dube (eds.), The Bible in Africa: Transactions, trajectories, and trends, pp. 569-581 Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Hoyland, M., 1998, 'An African presence in the Old Testament? David Tuesday Adamo's interpretation of the Old Testament cush passages', Old Testament Essays 11(2), 50-58. [ Links ]

Hoyland, M., 2000, 'The African texts of the Old Testament and their African interpretations', in M. Getui, K. Holter & V. Zinkuratire (eds.), Interpreting the Old Testament in Africa, pp. 43-54, Peter Lang, New York. [ Links ]

Jacob, E., 1958, Theology of the Old Testament, Baker, London. [ Links ]

Jonker, L., 2001, 'Toward a communal approach for reading the Bible in Africa', in M. Getui, K. Holter & V. Zinkuratire (eds.),Interpreting the Old Testament in Africa, pp. 76-88, Peter Lang, New York. [ Links ]

Knight, G.A.F., 1953, A biblical approach to the doctrine of the Trinity, Clark, Edinburg. [ Links ]

Krahmalkov, C.R., 2000, Phoenician-Punic Dictionary, Peeters, Leuven. [ Links ]

Masenya, M. (NgwanaMphalele), 2012, 'Her appropriation of Job's lament? Her lament of Job 3, from an African story-telling perspective', in M. Dube, A.M. Mbuvi & D.R. Mbuwayesango (eds.), Postcolonial perspectives in African biblical interpretations, pp. 283-298, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

Maspero, G., 1968, The dawn of civilization, vol. 1, Transl. by M.L McClure, Frederick Ungar Publication, New York. [ Links ]

McFall, E.A, 1970, Approaching the Nuer through the Old Testament, William Carey Library, Pasadena, CA. [ Links ]

Mendelssohn, C. & Barnett, C., 1987, Tharros: A catalogue of material in the British Museum from phoenician and other tombs at Tharros, Sardinai, British Museum Publications, London. [ Links ]

Moore, M.B., 2006, Philosophy and practice in writing a history of ancient, Clark, New York. [ Links ]

Mulrain, G., 1999, 'Hermeneutics within a Caribbean context', in R.S. Sirgirtharajah (ed.), Vernacular hermeneutics, pp. 116-132, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Nthaburi, Z. & Waruta, D., 1997, 'Biblical hermeneutics in African instituted churches' in H.W. Kinoti & J.M. Wallingo (eds.), The Bible in African Christianity, pp. 40-57, Acton Publishers, Nairobi. [ Links ]

Ogunfuye, J., n.d, The secrets of the uses of psalms, Ogunfuye Publications, Ibadan. [ Links ]

Ogunkunle, C., 2000, 'Imprecatory psalms: Their forms and uses in ancient Israel and some selected churches in Nigeria', Unpublished PhD. thesis, Department of Religious Studies, University of Ibadan. [ Links ]

Okure, T., 1996, 'Africans in the Bible: A study of hermeneutics', Paper presented at the annual meeting of SBL, New Orleans, LA, 22-26 November. [ Links ]

Oshitelu, I.O., n.d., 'The secret of meditation with God with the uses of psalms', Ogere Shagamu Publication, Church of the Lord, Aladura. [ Links ]

Procksch, O., 1967, 'The Word of God in the Old Testament', in G. Kittel, Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, p. iv, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Rawlinson, G., n.d., History of ancient Egypt, vol. 2, Clarke, Chicago, IL. [ Links ]

Riches, J., 1996, 'Interpreting the Bible in African contexts: Glasgow consultation', Semeia 73, 181-188. [ Links ]

Schmitz, P., 2002, 'Reconsidering phoenician inscribed amulet from the vicinity of Tyre', Journal of the American Oriental Society 122, 817-822. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3217621 [ Links ]

Shobat, E. & Stam, R., 1994, Unthinking eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the media, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Smart, N., 1969, Religious experience of mankind, Collins, New York. [ Links ]

Smart, N., 1973, The phenomenon of religion, Mowbrays, London. [ Links ]

Smoak, J., 2010, 'Amuletic inscriptions and the background of YHWH as Guardian and Protector in Psalm 12', Vetus Testamentum60(12), 421-432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156853310X504856 [ Links ]

Smoak, J., 2011, Prayer and petition in the psalms and West Semitic inscribed amulets: Efficacious words in metal and prayers for protection in biblical literature', Journal for the the Study of Old Testament 36(1), 75-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0309089211419419 [ Links ]

Sugirtharajah, R.S, 1999, 'Vernacular resurrections: An introduction', in R.S. Surgirtharajah (ed.), Vernacular hermeneutics, pp. 11-19, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Thielton, A., 1974, 'The supposed power of words', Journal of Theological Studies 25(2), 183-299. [ Links ]

Ukpong, J., 1995, 'Reading the Bible with African eyes: Inculturation and hermeneutics', Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 91, 3-14. [ Links ]

Ukpong, J., 2000, 'Development in biblical interpretation in Africa: Historical and hermeneutical directions' in G. West & M. Dube (eds.),Bible in Africa, pp. 11-28, Brill, Boston, MA. [ Links ]

Ukpong, J., 2001, 'Bible reading with a community of bible readers', in M. Getui, T. Maluleke & J. Ukpong (eds.), Interpreting the New Testament in Africa, pp. 188-212, Acton Press, Nairobi. [ Links ]

Ukpong, J., 2002, 'Inculturation hermeneutics: An African approach to biblical interpretation', in W. Dietrich & U. Luz (ed.), The Bible in a world context: An experiment in contextual hermeneutics, pp. 17-32, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Von Rad, G., 1965, Old Testament theology, vol. 2, Clark, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

West, G., 2002, 'Unpacking the package that is the Bible in African biblical scholarship', in A. Masoga, N.K. Gottwald, T.S. Maluleke, J.S. Ukpong, G.O. West, J. Punt, V.L. Wimbush & M.W. Dube (eds.), Reading the Bible in the global village, pp. 65-94, Society of Biblical Literature, Atlanta, GA. [ Links ]

West, G., 2009, 'Interrrogating the Comparative Paradigm in African Biblical Scholarship', in H. de Wit & G. West (eds.), African and Eurpean Readers of the Bible in Dialogue, pp. 37-64, Cluster Publications, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Wilks, I., 1970, 'Africa historiographical traditions, old and new', in F.D. Page, Africa discover her past, pp. 4-7, Oxord University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Wimbush, V., 2009, 'Scripture for strangers: The making of an Africanized Bible', in T-S. Liew (ed.), Postcolonial interventions, pp. 162-177, Sheffield Phoenix Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Yorke, G.L., 1995, 'Biblical hermeneutics: An Afrocentric perspective', Journal of Religion and Theology 2(2), 145-158.http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/157430195X00096 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

David Adamo

adamodt@yahoo.com

Received: 20 Apr. 2015

Accepted: 26 Oct. 2015

Published: 08 July 2016

1 See further explanation in Adamo (2001a).

2 Several terms are related to this transformational hermeneutics: inculturation hermeneutics, liberation hermeneutics, contextual hermeneutics, Africentric hermeneutics, and vernacular hermeneutics. From the above, African cultural hermeneutics is not done in absolute exclusion of Western biblical theology. It is complimentary.

3 Postcolonial here refers to a particular approach or theory.

4 I may be accused of been bias by some Western and African readers of this article. However, the fact is that there is no 100% objectivity in scholarship. A close examination of the history of hermeneutics shows that there is no 100% objectivity, mostly by the social location of the scholar - Western or African (Moore 2006:8-11).

5 I consider it to be potent words instead of incantations.

6 At the conference of the Nigerian Association for Biblical Studies, Ibadan, on 23-25 July 2014, several African scholars and non-scholars questioned the rationale for returning to African indigenous religion.

7 I will use this term instead of Afrocentric since it comes from the word Afri-ca and not Afro-ca.

8 It is prejudice that will make anyone who calls him - or herself a biblical scholar to say that African Biblical Studies is not part of biblical studies. It may also be as a result or ignorance of the actual trend of African Biblical Studies (cf. Dube 2012:29-42).

9 This is not magic but the recitation is based on faith. If this is considered magic, then the Bible must be magical when the names of God are recited over and over again.

10 Even though it may not be an absolute proof, the likelihood is strong.

11 The similar way Africans use psalms is not in only one way. Africans also use psalms liturgically because the worldview of Africans is very similar. Only those who are not knowledgeable about African worldview will deny this.

12 Several terms are related, though not the same to these transformational studies, namely inculturation studies, liberation hermeneutics, contextual studies, Africentric studies, and vernacular hermeneutics. From the above it is clear that African cultural studies are not done in absolute exclusion of Western biblical methodology. It can be complementary.

13 Reading papers at the meeting of SBL on African presence does not mean that such papers are accepted and that African presence is accepted by many Western scholars. This writer was once accused of trying to smuggle Africa and Africans into the Bible when he submitted articles on the presence of Africa and Africans in the Old Testament.

14 This article may sound ideological, but it is not. After all, is the Bible not ideological?

15 As much as their efforts should be commended on they have not really included some aspects of this African Biblical Studies such as the use of the Bible as incantation, amulets and the idea of blackening of the Bible. To say that the call for recognition of African Biblical Studies is 'outdated and unnecessary' is an illusion. African biblical scholars and others who are committed to this must be committed to further explain what it is, for the whole world to understand. There is a need to further discover new things about African Biblical Studies.

16 Numbers 12:1-9; the Queen of Sheba (1 Ki 10:13); Kushi, African in David military personnel (2 Sm 18:21-32.

17 I should not be misunderstood. This is not to say that unless a cultural group can identify themselves in the Bible the Bible is not meaningful to them. However, the identification of Africa and Africans in the Bible enhances Africans' belief and identifying with the Bible. It can also help to take away the inferiority complex and enhances the belief that Christianity is not a white man's religion alone but also an African religion.

18 The story of Exodus is too vivid and too repetitive in every strand of biblical literature.

19 The blackening of the Bible is not a replacement of Western interpretation. It only takes the lead when used in conjunction with the Western interpretation rather than the Western interpretation taking the lead. It may sound ideological but to my knowledge there is no interpretation at all that is ideologically free.

20 To my knowledge no race has been that historically marginalised as the black race, especially from Africa.