Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

In die Skriflig

versión On-line ISSN 2305-0853

versión impresa ISSN 1018-6441

In Skriflig (Online) vol.49 no.1 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/IDS.v49i1.1987

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The missional role of the Holy Spirit: Ghanaian Pentecostals' view and practice

Die missionale werk van die Heilige Gees vanuit die teologie en praktyk van Ghanese Pinksterkerke

Peter White; Cornelius J.P. Niemandt

Department of Science of Religion and Missiology, Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article discusses the missional role of the Holy Spirit from a Ghanaian Pentecostal's perspective. In doing this, trinitarian mission is used as the point of departure and it was narrowed down to the missional role of the Holy Spirit. The Ghanaian Pentecostals' view about the baptism and the infilling of the Holy Spirit as well as their practices concerning the subject are discussed. The article concludes that there is no way that the church could achieve her call without the role of the Holy Spirit, to convict sinners of their sin and also to empower the church to proclaim the gospel.

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel bespreek die missionale werk van die Heilige Gees vanuit die teologiese perspektief en praksis van die Pinksterkerke in Ghana. Die artikelvertrekpunt is 'n trinitariese benadering tot sending, en van daaruit word die rol en plek van die Heilige Gees in die sending van God bespreek. Die artikel gee ook aandag aan die siening omtrent die doop en die vervulling met die Heilige Gees onder Pinksterkerke in Ghana, asook aan kerklike praktyke wat uit hierdie teologiese standpunt spruit. Die artikel argumenteer dat die kerk net aan haar missionale roeping getrou kan wees op grond van die Heilige Gees se rol om sondaars van sonde en verlossing te oortuig, en die Gees se bemagtiging van gelowiges om die evangelie te verkondig deur die verskeidenheid gawes wat die Gees gee.

Introduction

Roamba (2006:11-15) notes that very little has been written on the role of the Holy Spirit as a missionary spirit with regard to West African churches. Though this claim may not be true in some West African churches, it is, however, true in the context of the Ghanaian Pentecostal churches. A review of some books and academic research on Pentecostalism in Ghana attests to this fact. A study of Omenyo's (2006), Pentecost outside Pentecostalism, and that of Larbi (2001), Pentecostalism: The eddies of Ghanaian Christianity, shows that these books are geared towards a historical search of the emergence of Pentecostalism in Ghana. Asamoah-Gyadu (2005; 2013a), on the other hand, presents an overview of Pentecostalism in Ghana. Just like Omenyo, Abamfo's (1993) study of Pentecostalism in Ghana focuses on the rise of charismatic movements in the mainline churches in Ghana. Onyinah's (2002) doctoral research addresses Akan witchcraft and the concept of exorcism in the Pentecostal church. Gbekor (1998) and Amoah's (2000) research throw light on the renewal movement (charismatic movement) in the Evangelical Presbyterian Church. Furthermore, Lauterback's (2008) research on the Ghanaian Pentecostal phenomenon explores the social and political implications of the Neo-Pentecostal (or Third Wave) ideas, institution and actors in present-day Ghana.

A study of the fore-mentioned literature reveals that though some aspects of Pentecostalism in Ghana are discussed, nothing is, however, said about the missional role of the Holy Spirit. This article therefore seeks to address this research gap from a Ghanaian Pentecostal's perspective. It would also serve as a foundation for further research since Ghanaian Pentecostal Churches have little documented information on the subject under discussion.

For the purpose of this article, Ghanaian Pentecostals are referred to as a group of Christians who emphasise salvation in Christ as the basis for one to be filled with the Holy Spirit, and in which the 'Spirit phenomenon' (including speaking in tongues, prophecies, visions, healing and miracles in general) is perceived to be in line with what happened in the Early Church in the Acts of the apostles and is accepted as a continuous experience in the contemporary church as a sign of the presence of God and an experience of his Spirit (Asamoah-Gyadu 2005:12). What defines Pentecostalism is the experience of the Holy Spirit in transformation, radical discipleship and manifestations of the acts of power that demonstrate the presence of the kingdom of God amongst his people (Asamoah-Gyadu 2013a:10-11). The Holy Spirit is therefore the power of the transition, mediation, communication and history which takes place firstly in the life of God himself, and then consequently in our life and our relationship with Christ Jesus (Flett 2010:239). The Holy Spirit is constantly at work in ways that surpass human understanding and in places that are least expected (World Council of Churches 1992:43). In Ghana one finds the classical Pentecostal churches and the Neo-Pentecostal churches. The classical Pentecostals are the four mainline Pentecostals churches, namely the Christ Apostolic Church International; The Apostolic Church, Ghana; The Church of Pentecost (CoP); and the Assemblies of God-Ghana. The Neo-Pentecostals are the charismatic churches and the independent Pentecostal churches popularly known as 'one man churches'. Typologically, both the classical Pentecostal churches and the Neo-Pentecostal churches are grouped under Pentecostal churches and fall under the umbrella of the Ghana Pentecostals and Charismatics Council.

The views presented in this article were informed by a literature study of statements and the doctrinal documents of Pentecostal churches in Ghana, as well as a broader literature study on the issue of the role of the Holy Spirit in mission (i.e. ecumenical statements of the Lausanne Movement and the World Council of Churches). It was also informed by interviews with some Ghanaian Pentecostal leaders and observation of how the subject under discussion is being treated as far as pentecostalism in Ghana is concerned.

In view of the objectives of the research, the discussion starts with the trinitarian mission and then narrows down to the missional role of the Holy Spirit. The Ghanaian Pentecostal's view about the baptism and the infilling of the Holy Spirit as well as their practices concerning the subject are also discussed.

Trinitarian approach to mission

Until the 16th century, when the Jesuits first began to use the term mission with reference to the spreading of the gospel to people who were not Christians, mission was exclusively used in reference to the doctrine of the Trinity. That is the sending of the Son by the Father and of the Holy Spirit by the Father and the Son (Bosch 1991:1). According to LaCugna (1991:228), the doctrine of the Trinity is not only about God but also about God's life with us, and our life with each other. It is a life of communion and indwelling, God in us and we in God; all of us together. This view implies that mission is about God and his historical redemptive initiative on behalf of creation (missio Dei). Furthermore, it also refers to all the specific and varied ways in which the church crosses cultural boundaries to reflect the life of the triune God in the world, and through that identity, participates in his mission (Tennent 2010:59). In describing the historical redemptive work of the triune God, Wright (2006:48-51) proposes a missional-biblical hermeneutic. In his view, the whole Bible shows us the story of God's mission through God's people in their engagement with God's work for the sake of the whole of creation. Biblically, the point of departure for the trinitarian mission approach was clearly presented by Jesus Christ in John 20:21-22 when he said, as the Father has sent me, I am sending you'. And with that he breathed on them and said, 'receive the Holy Spirit'. In the context of Jesus' statement, the Father is the Sender, the Lord of the harvest; the incarnated Son is the model embodiment of the Father's mission in the world; and the Holy Spirit is the divine empowering presence for the entire mission (Tennent 2010:75).

Saayman (2010:13) submits that the term missional is meant to refer fundamentally to the missio Dei, just as the term missionary does. He further argues that in terms of its deepest, fundamental understanding, both missional and missionary verbalise the phenomenon that we understand as missio Dei (Saayman 201015). In fact, without the missio Dei, the mission of the church would simply be a grasping at mere straws; it would be salvation by works alone. Mission is more than mere human activity reliant on emotion, volition and the action of finite beings. Mission, rightly, belongs to God; and anything other than the missio Dei being the starting point and climax of redemptive action is no more than an impediment to the proclamation of the true gospel message. The missio Dei is not something from which the Christian community can depart (Flett 2010:9). The participation of the church in the divine mission was expanded during the ecumenical discussions of the 20th century (Balia & Kim 2010:23). The relationship of the divine persons in the Trinity to one another is so extensive that it has room for the whole world (Moltmann 1993:30). This understanding has therefore presented the church as a model of the manifestation of the existing relationship in the Trinity (Zizioulas 1995:20). The Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization (2010) puts it this way:

The mission of God continues to the ends of the earth and to the end of the world. The day will come when the kingdoms of the world will become the kingdom of our God and of his Christ and God will dwell with his redeemed humanity in the new creation. Until that day, the Church's participation in God's mission continues, in joyful urgency, and with fresh and exciting opportunities in every generation including our own. (p. 5)

In the concept of missio Dei, the Holy Spirit has a wholly unique personhood, not only in the form in which he is experienced, but also in his relationship to the Father and the Son (Moltmann 1992:12). This relationship was clearly noted when Jesus said at Nazareth: 'The Spirit of the Lord is upon me' (Lk 4:18). A pneumatological mission theology was therefore propounded at this point by Jesus Christ (Balia & Kim 2010:24), and this was also why the disciples could not do anything after the ascension of Jesus Christ until they received the power of the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost.

The CoP1 (2013) affirms their belief in the triune God in the following statement:

We believe in the existence of the One True God, Elohim, Maker of the whole universe; undefinable, but revealed as Triune God, Father, Son and the Holy Spirit - One in nature, essence, and attributes, Omnipotent, Omnipresent.

This view of the triune God has also influenced their approach to mission (CoP 2013; Larbi 2001:280-281). In fact, one could relate this doctrinal position of the CoP to the new WCC affirmation (2013) on mission and evangelism. It says:

We believe in the Triune God who is the Creator, Redeemer and Sustainer of all life. God created the whole oikoumene in God's image and constantly works in the world to affirm and safeguard life. We believe in Jesus Christ, the Life of the world, and the incarnation of God's love for the world. Affirming life in all its fullness is Jesus Christ's ultimate concern and mission. We believe in God the Holy Spirit, the Life-giver, who sustains and empowers life and renews the whole creation. A denial of life is a rejection of the God of life. God invites us into the life-giving mission of the Triune God and empowers us to bear witness to the vision of abundant life for all in the new heaven and earth. (p. 51)

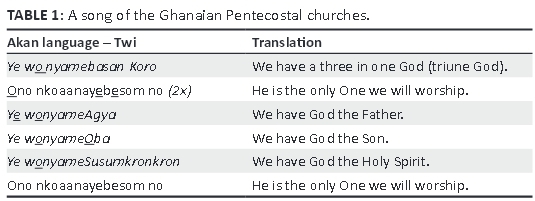

This implies that the Ghanaian Pentecostals' missiological understanding of the triune God is not far from that of the Ecumenical movement. In addition to the Ghanaian Pentecostals' doctrinal position on the triune God, this view also appears in their songs. In their meetings, they also sing various songs (cf. Table 1: 'A song of the Ghanaian Pentecostal churches').

The submission at this point is that no matter the kind of mission model one has in mind, that mission model must recognise that mission is primarily God's mission. The ultimate goal of the missio Dei is to manifest the glory of God on earth, to establish his reign in the hearts of people -evidenced by the conversion of souls and resulting in love, equality, diversity, mercy, compassion and justice amongst God's creation (Kirk 1999:28).

Missional role of the Holy Spirit

According to the CoP, the Holy Spirit as the mysterious third Person of the Trinity through whom God acts, reveals his will, empowers individuals, and discloses his personal presence in the Old and New Testament (CoP 2013). In many pentecostal circles in Ghana, they mostly use the term Holy Ghost for the Holy Spirit. Van Aarde (1999:245), in this regard argues that the term Ghost - when used for the Holy Spirit -is a misleading translation of the Greek word 'πνεΰμα' (which means spirit), and that there is no word in Greek for Spirit. He points out that the closest word is 'φάντασμα' which means apparition. But this word is never used for the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is a Person in the same sense that the Father and the Son are Persons. He emphasised that the term Spirit relates to the distinct role of his Person, since the Father and the Son are also spirit. This argument of Van Aarde is thought provoking and will require a further study, which could be done in a later Pentecostal's Pneumatological or exegetical research.

From the Pentecostals' perspective, the role of the Holy Spirit has been paramount in the missio Dei process. He has been active in the Old Testament, in creation, in redemption, and in various other spiritual undertakings. In the New Testament, however, his work becomes totally and evidently apparent and prominent with regard to world mission (Schweer 1998:108; Van Aarde 1999:250). This implies that the starting place for considering the spiritual dynamics of mission must be in recognising the role of the Holy Spirit (Ott, Strauss & Tennent 2010:240). Christian mission in this regard could be defined as the proclamation of the kingdom of the Father, as sharing the life of the Son and bearing the witness of the Holy Spirit (Newbigin 1978:31). Newbegin (1978:66) further states that mission is the action of the Holy Spirit who in his sovereign freedom both convicts the world, and also leads the church toward the fullness of the truth which it has not yet grasped. The ultimate missional role of the Holy Spirit is to make Jesus Christ known to the world and his saving power through his death and resurrection. The Holy Spirit is seen as the continuing presence of Christ, and his agent to fulfil the task of mission. This understanding leads to a missiology focusing on sending out and going forth. In a personal interview on 20 April 2014, apostle Donkor of the Christ Apostolic Church International states that pneumatological focus on Christian mission recognises that mission is essentially Christologically based and relates to the work of the Holy Spirit to salvation through Jesus Christ. This is done through the participation of the church in God's ongoing work of liberation and reconciliation through the Holy Spirit. It includes discerning and unmasking the demons that exploit and enslave people.

In addition to the views discussed, the missional role of the Holy Spirit is not limited to the unbelievers, but it is also extended to believers in order to fulfil their ministry in the church and their mission in the world (CoP 2014a:26; Russell 1988:133-134). The Holy Spirit, for example came upon the disciples on the day of Pentecost for the purpose of equipping them to begin the mission entrusted to them (Acts 2:1-41). This role of the Holy Spirit in believers therefore includes empowering believers for mission and character development, which could also be called the 'life in the Holy Spirit' (Leonard 1989:15). According to the World Council of Churches (2013:52, 58) life in the Holy Spirit is the essence of mission, the core of why we do what we do, and how we live our lives. Spirituality gives the deepest meaning to our lives and motivates our actions. Experiencing life in the Spirit is to taste life in its fullness; the Holy Spirit meets us and challenges us at all levels of life, and brings newness and change to the places and times of our personal and collective journeys.

In line with this view, Ghanaian Pentecostals preach and emphasise that every Spirit filled believer should live according to the Word of God and should show good conduct (morally and spiritually) in all that they do. Many times this emphasis is based on Jesus' statement, 'By their fruit you will recognize them ...' (Mt 7:15-20). In the Pentecostals interpretation of the Word, fruit used in this context is a figure of speech for their character, the product of their life, their actions and their moral conduct. Their argument is that it is therefore expected of the spirit filled believer to bear the fruit of the Holy Spirit, since the Holy Spirit is living in them and also helping them to live a 'Christlike' life (CoP 2014b).

In a nutshell, the activities of the Holy Spirit in the age of the church include amongst other things, attracting people to Christ, convicting them of truth, regeneration, baptism, indwelling, filling, sealing, guaranteeing, spiritual gifts, fruit of the Spirit, helping to understand the Scripture, and empowering believers. It is noteworthy that Pentecostals point to the Scriptures, particularly to Pauline thought, as the primary source of authority in matters of faith. For them, every time the apostle Paul uses the expression 'spiritual' it refers to the working of the Holy Spirit (Asamoah-Gyadu 2013b:11)

The Holy Spirit and the believer: Ghanaian Pentecostals' view and practices

In Ghanaian Pentecostal churches' understanding, after one has received Jesus Christ as his or her personal Lord and Saviour (become a believer), the second thing the believer should seek in order to live a Christ like life and to fulfil their ministry, is to be baptised or filled with the Holy Spirit. The CoP (2014a) holds that:

All believers in Christ Jesus are entitled to receive, and should earnestly seek, the Baptism of the Holy Spirit and fire according to the command of our Lord Jesus Christ. This is a normal experience of the Early Church. With this experience comes power to preach and bestowment of the gifts of the Holy Spirit. The believer is filled with the Holy Spirit; there is a physical sign of 'speaking in other tongues' as the Spirit of God gives utterance. This is accompanied by a burning desire and a supernatural power to witness to others about God's salvation power. (pp. 19-21; cf. also Asamoah-Gyadu 2013b:14; Larbi 2001:278)

In practice, many Ghanaian Pentecostal churches use the following Bible verses and approaches in their teaching on the 'baptism or infilling of the Holy Spirit'. The term 'baptism or infilling of the Holy Spirit' is used at this point because it is noticed that many Pentecostal churches in Ghana do use it interchangeably. However, it should be clearly noted that through the baptism of the Holy Spirit believers are incorporated in the body of Christ. The second thing believers should seek, after becoming born again, is the power to walk in the newness of life that they have received - this comes through the infilling of the Holy Spirit. Although there is only one 'baptism', there are many infillings.

In Ghanaians' Pentecostal view, one could be filled with the Holy Spirit through a variety of practices.

The desire or thirst for the infilling of the Holy Spirit

At the various Holy Spirit services of Pentecostal churches in Ghana, leaders of the programme usually encourage those who have not received the infilling of the Holy Spirit to have the desire or the thirst for the infilling of the Holy Spirit (CoP 2014a:33). John 7:37-39 and Matthew 6:5 are many times cited in support of this claim. Members are told that the 'thirst' could mean an earnest desire for something (Mk 11:24; 1 Cor 14:1). They therefore place emphasis on Jesus' statements in John 7:37-38 and Mark 11:24, as evidence to show that one of the means of receiving the infilling of the Holy Spirit is by desiring or thirsting for it (CoP 2014a:30).

Pray in faith and ask the Father to fill you with the Holy Spirit

The second approach, amongst Pentecostals to enable believers to be filled with the Holy Spirit is that members are encouraged to pray in faith and ask the Father to fill them with the Holy Spirit. In doing this they refer to Jesus' statement on being persistent in prayer, in relation to asking the Father to fill believers with the Holy Spirit (Lk 11:9-13). The other part of this aspect is the exercising of the faith of members, in order to be filled with the Holy Spirit. They often stress that it is not enough to pray, one also has to exercise one's faith (Murphy & Murphy 2000:485-486). In a meeting at the Revival Life Outreach Church in Kumasi, Ghana, the senior pastor, Rev. Paul Owusu Yeboah, told the congregants who were seeking to be filled with the Holy Spirit, to support their prayer with their faith.

The practice of the laying-on of hands

The third approach of Pentecostals to enable believers to be filled with the Holy Spirit is the practice of the laying-on of hands on those who are yearning for it (CoP 2014a:30). Many of Ghanaian Neo-Pentecostals (Revival Life Outreach Church, Action Chapel International, and Perez Chapel) mostly rely on Hagin's (1995:5) assertion, which says that 'even if a Spirit-filled believer does not have this ministry of laying-on of hands, it is all right for him to pray with the candidate, because it releases the candidate's faith'. They therefore rely on the following Bible references as examples for the practice:

• Moses laid his hand upon Joshua - Deuteronomy 34:9.

• The apostles Peter and John laid their hands on some believers in Samaria - Acts 8:14-17.

• Ananias laid his hands on Saul - Acts 9:12, 17.

• The apostle Paul laid his hand on some believers in Ephesus - Acts 19:1-7.

In reference to the Pentecostal's teachings and practices on the infilling of the Holy Spirit, it must be kept in mind that although the above-mentioned ways are biblical examples, that the Lord can simply fill anyone with the Holy Spirit in any setting or circumstance he chooses. God is sovereign and can decide to do anything at any time.

Maintaining the infilling of the Holy Spirit

The word, maintain, used here is to propound the idea of consistency in one's relationship with the Holy Spirit. Many Ghanaian Pentecostal churches, on this matter, state that the apostle Paul - in establishing his argument on this view -admonished believers to be continuously filled with the Holy Spirit (CoP 2014a:30; Eph 5:18); and in 1 Thessalonians 5:19 Paul said, 'Quench not the Spirit'. In Paul's advice to Timothy, the Bishop of the Church in Ephesus, the apostle said: 'Wherefore I put thee in remembrance that thou stir up the gift of God, which is in thee by the putting on of my hands' (2 Tm 1:6).2 According to Lin (2002:53-54), the admonition of not quenching the Spirit is a command in the present tense that indicates that we should always refrain from extinguishing the activities of the Holy Spirit. He finally submits that, to defuse the danger of quenching the Spirit, there are certain things that we must constantly do. Lin mentions prayer and a consistent study of the Bible as some of the ways to achieve this purpose. In like manner, Ghanaian Pentecostals share the same view.

Prayer

Unlike the Christ Apostolic Church - where the constitution has a lot to say on the how, where, when and why of prayer -the CoP has nothing of that sort - they just pray. Everything within the church begins and ends with several minutes of prayer. Apart from encouraging people to pray individually, they also practice mass or congregational prayer, a type of prayer that they believe was practiced by the Early Church (Larbi 2001:257). Many Ghanaian Pentecostals see prayer as one of the ways one can use to maintain one's spiritual relationship with God (Agyin-Asare 2001:7).

In order to enforce the culture of prayer in their members, many of the Pentecostal churches in Ghana have set days (such as Wednesdays and Fridays) for prayer meetings; some of which are in the morning, and others in the afternoon, or evening. These prayer meetings are organised in forms such as revival or miracle services, all night prayer and deliverance services. They mostly name such prayer meetings MpaeboKesee, meaning 'big prayer', or Ntentam, meaning 'wrestling in prayer', an idea taken from the apostle Paul (Eph 6:12; Agyin-Asare 2001:16). Other names given to these meetings are: 'Jericho hour', 'hour of divine visitation', 'hour of grace', 'hour of divine intervention', 'hour of divine breakthrough', 'hour of restoration', and 'hour of prophetic unction' (Asamoah-Gyadu 2013a:35-38). Thus, in Pentecostal thought, prayer is an activity inspired primarily by a certain understanding of the working of the Holy Spirit as the believer's source of empowerment (Asamoah-Gyadu 2013a:35).

Diligent study of the Scriptures

Pentecostals also encourage their members to develop a daily personal Bible study life. They are of the view that Bible study is also one of the ways one can become more in tune with the Holy Spirit. In a personal interview on 15 July 2013 with Rev. Ekow Eshun, the General Overseer of the Revival Life Outreach Church in Kumasi in Ghana, he said that some people always try to brush out certain verses and quotations. Their interest is to study things that will satisfy their selfish desires. Referring to 2 Timothy 3:14-17, Eshun emphasised that every portion of the Bible is of great importance to believers. Hampton (2013) argues that whilst believers study the Bible for spiritual growth, it reflects in the change in their character through the renewing of their mind. This change in ones thought and character is through the Holy Spirit.

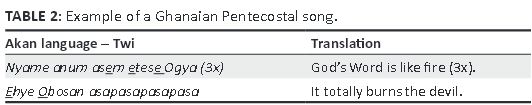

The strong emphasis the Ghanaian Pentecostal church places on belief in the Bible is demonstrated in the songs sung at their meetings. One of them is presented as an example below (cf. Table 2: 'Example of a Ghanaian Pentecostal song').

Sanneh (1983:180) argues that the submission of the Bible to the regenerative capacity of African perception is what led to the renewal of Christianity through the independent and indigenous churches of Africa. Throughout Africa Scripture is held in high esteem because of its relevance to the realities in many African communities (Jenkins 2006:18, 23).

Missiological implication of Ghanaian Pentecostals practices

The Pentecostal experience of the Holy Spirit is an integral aspect in the African theology of missions (Roamba 2006:12). An important element of Pentecostal spirituality is the emphasis on the 'gift of the Spirit' which is often expressed in their literature as 'charismatic gifts' (Asamoah-Gyadu 2005:7). Pentecostals aim at revivalism and the renewal of the world of Christianity. Its emphasis in the modern world is on revivalism in the Christian life as a live experience of the Holy Spirit that must be renewed time and again. Contemporary manifestations of pentecostalism are often classified in terms of 'charismatic renewal' as a result of their general orientation towards the restoration of the gifts of the Holy Spirit. This include speaking in tongues, prophesy, healing, visions, and revelations to the heart of people (Asamoah-Gyadu 2005:5). In their theology, the practice of infilling or baptism of the Holy Spirit, which is often followed by speaking in tongues, is not the end of one's spirituality, but a way leading to the Holy Spirit endowment for ministry within the church and mission to the world (Asamoah-Gyadu 2013b:11; CoP 2014a:22-24). A position similar to Ghanaian Pentecostal churches can be found in the Lausanne Confession (2010) in the following words:

The church is called to witness to Christ today by sharing in God's mission of love through the transforming power of the Holy Spirit. The Spirit fills the Church with his gifts, which must be 'eagerly desired' as the indispensable equipment for Christian service. The Spirit gives power for mission and for the great variety of works of service. Without the gifts, guidance and power of the Spirit, our mission is mere human effort. And without the fruit of the Spirit, our unattractive lives cannot reflect the beauty of the gospel. (p. 10)

The Holy Spirit gives gifts freely and impartially which are to be shared for the building up of others and the reconciliation of the whole creation (WCC 2013:56). In Ghanaian Pentecostals' understanding, the Holy Spirit can use any of the gifts to present the gospel to others as it was in the case of Stephen and Philip who started their ministry as deacons but ended as evangelists (CoP 2014a:24, 26; Acts 6-8). This implies that the gifts of the Holy Spirit are given for a common good and place obligations of responsibility and mutual accountability on every individual and local community and on the church as a whole at every level of its life. In other words, through the infilling of the Holy Spirit believers are endowed with diverse spiritual gifts that will enable them to be involved in the missio Dei. In this regard, Ghanaian Pentecostal churches see the teachings and the practices that will help their congregation to be filled with the Holy Spirit as an integral part of their missional spirituality.

Conclusion

This article discusses the missional role of the Holy Spirit from a Ghanaian Pentecostal's perspective. In doing this, the trinitarian mission approach became the point of departure and it was narrowed down to the missional role of the Holy Spirit. The article argues that the missional role of the Holy Spirit is not limited to unbelievers but also to believers. It also submits that the missional role of the Holy Spirit to unbelievers is to convict them of their sins and the need for Jesus Christ as the solution. On the other hand, the role of the Holy Spirit with regard to believers includes empowering them for ministry and mission as well as personal character building. With this view, Ghanaian Pentecostals have therefore put in place practices that would help believers to be filled with or baptised in the Holy Spirit. This practice is not only for personal benefits, but serves as a means to experience greater spirituality through the endowment and manifestations of spiritual gifts in the lives of believers for the purpose of ministry in the church and mission. The role of the Holy Spirit is this regard, is integral in every phase of the mission of the church. Without the Holy Spirit the mission of the church will be a mere human activity, and will not yield results that would bring glory to God. Churches have to therefore join in with the Holy Spirit to discern what the Father is doing in their context and do the same.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

Dr Peter White (University of Pretoria) is a postdoctoral research fellow of Prof. Nelus Niemandt, Head of the Department of Science of Religion and Missiology of the Faculty of Theology, University of Pretoria, South Africa. He did the field work and the write up for the article, and Prof. Niemandt provided the theoretical idea on how to integrate the Pentecostal ideas into the broader missiological dialogue.

References

Abamfo, O.A., 1993, The rise of charismatic movement in the mainline churches in Ghana, Asempa Publishers, Accra. [ Links ]

Agyin-Asare, C., 2001, Power in prayer: Taking your blessing by force, His Printing, Hoornaar. [ Links ]

Amoah, G., 2000, 'Schisms in the Evangelical Church of Ghana', MPhil thesis, Dept. for the Study of Religions, University of Ghana, Accra. [ Links ]

Asamoah-Gyadu, J.K., 2005, African charismatics: Current developments within independent indigenous pentecostalism in Ghana, Brill, Leiden. [ Links ]

Asamoah-Gyadu, J.K., 2013a, Contemporary Pentecostal Christianity, Regnum Books International, Eugene. [ Links ]

Asamoah-Gyadu, J.K., 2013b, 'The promise is for you and your children: Pentecostal spirituality, mission and discipleship in Africa', in M. Wonsuk & J.K. Ross (eds.), Regnum Edinburgh Centenary Series, vol. 14, p. 11, Regnum Books International, Oxford. [ Links ]

Balia, D. & Kim, K. (eds.), 2010, Witnessing to Christ today, vol. 2, Regnum Books International, Oxford. [ Links ]

Bosch, J.D., 1991, Transforming mission: Paradigm shifts in theology of mission, Orbis, Maryknoll. [ Links ]

Church of Pentecost (CoP), 2013, Ten tenets of the Church of Pentecost, Ghana, viewed 12 August 2013, from http://www.thecophq.org/pages.php?linkID=4&linkObj=cat [ Links ]

Church of Pentecost (CoP), 2014a, Home cell study guide, Pentecost Press, Dansoman. [ Links ]

Church of Pentecost (CoP), 2014b, Core values, viewed 08 January 2014, from http://www.thecophq.org/pages.php?linkID=2&linkObj=cat [ Links ]

Flett, J.G., 2010, The witness of God: The Trinity, missio Dei, Karl Barth and the nature of Christian community, Kindle edn., Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Gbekor, C., 1998, 'The Bible study and prayer fellowship of the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Ghana', MPhil thesis, Dept. for the Study of Religions, University of Ghana, Accra. [ Links ]

Hagin, K.E., 1995, Seven vital steps to receiving the Holy Spirit, 2nd edn., Faith Library Publications, Tulsa. [ Links ]

Hampton, K.J., 2013, The spirit-filled life, viewed 17 August 2013, from http://bible.org/seriespage/spirit-filled-life-part-2 [ Links ]

Jenkins, P., 2006, The new faces of Christianity: Believing the Bible in the Global South, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Kirk, J.A., 1999, What is mission? Theological explorations, Darton, Longmann & Todd, London. [ Links ]

LaCugna, C.M., 1991, God for us: The Trinity and Christian life, Harper, San Francisco. [ Links ]

Larbi, E.K., 2001, Pentecostalism: The eddies of Ghanaian Christianity, Blessed Publications, Accra. [ Links ]

Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization, 2010, Third Lausanne Congress: Cape Town Commitment, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Lauterback, K., 2008, 'The craft of pastorship in Ghana and beyond', PhD thesis, Graduate School of International Development Studies, Roskilde University, Roskilde. [ Links ]

Leonard, C., 1989, A giant in Ghana: 3000 churches in 50 years - The story of James Mckeown and the Church of Pentecost, New Wine Press, Chichester. [ Links ]

Lin, T., 2002, How the Holy Spirit works in believers life today, Biblical Studies Ministries International, Bennett Court, Carmel. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J., 1992, Spirit of life: A universal affirmation, Fortress, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Moltmann, J., 1993, The church in the power of the Spirit: A contribution to messianic ecclesiology, transl. M. Kohl, Fortress, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Murphy, J.O. & Murphy, C.S., 2000, An international minister's manual, Hundredfold Ministries International, Arusha. [ Links ]

Newbigin, L., 1978, The open secret, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Omenyo, C.N., 2006, Pentecost outside pentecostalism, Boekencentrum, Zoetermeer. [ Links ]

Onyinah, O., 2002, 'Akan witchcraft and the concept of exorcism in the Church of Pentecost', PhD thesis, Dept. of Theology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham. [ Links ]

Ott, C., Strauss, S.J. & Tennent, T.C., 2010, Encountering theology of mission: Biblical foundation, historical developments, and contemporary issues, Baker Publishing, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Roamba, J.B., 2006, 'A West African missionary church', in S.M. Burgess (ed.), Encyclopaedia of pentecostal and charismatic Christianity, pp. 11-15, Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Russell, S.P., 1988, 'The pentecostal view', in D.L. Alexander (ed.), Christian Spirituality: Five views of sanctification, pp. 133-134, InterVarsity, Downers Grove. [ Links ]

Saayman, W., 2010, 'Missionary or missional? A study in terminology', Missionalia 38(1), 13, 15. [ Links ]

Sanneh, L.O., 1983, West African Christianity: The religious impact, Orbis, Maryknoll. [ Links ]

Schweer, W.G., 1998, 'The missionary mandate of God's nature', in J.M. Terry, E.C. Smith & J. Anderson (eds.), Missiology: An introduction to the foundations, history and strategies of world missions, p. 108, Broadman & Holman, Nashville. [ Links ]

Tennent, T.C., 2010, Invitation to world mission: A trinitarian missiology for the twenty-first century, Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Van Aarde, A., 1999, 'The Spirit of God in the New Testament: Diverse witnesses', HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 55(1), 245, 250. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v55i1.1554 [ Links ]

World Council of Churches (WCC), 1992, 'Ecumenical affirmation: Mission and evangelism', in J.A. Scherer & S.B. Bevans (eds.), New directions in mission and evangelization, vol. 2: Theological foundations, p. 43, Orbis, Maryknoll. [ Links ]

World Council of Churches, 2013, Together towards life: Mission and evangelism in changing landscapes, Resource book, WCC 10th Assembly, Busan, Geneva. [ Links ]

Wright, C.J.H., 2006, The mission of God, IVP Academic, Downers Grove. [ Links ]

Zizioulas, J.D., 1995, Being as communion: Studies in personhood of the church, St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, Crestwood. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Peter White

Private Bag X20

Hatfield 0028, South Africa

Email: pastor_white@hotmail.com

Received: 12 May 2015

Accepted: 12 Aug. 2015

Published: 30 Sept. 2015

Note: This article was presented at the Southern African Missiological Society Annual Conference held at North-West University, Mafikeng Campus, Mafikeng, South Africa, from 12-14 March 2014.

1 The Church of Pentecost is one of the four main classical Pentecostal churches in Ghana.

2 This view is the position of many Pentecostal churches in Ghana. They usually preach and teach their members on the importance of being filled with the Holy Spirit.