Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

In die Skriflig

On-line version ISSN 2305-0853

Print version ISSN 1018-6441

In Skriflig (Online) vol.47 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2013

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Indicators of the church in John's metaphor of the vine

Aanwysers van die kerk in John se metafoor van die wingerdstok

Johann Fourie

Faculty of Theology, Northwest University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article aims to answer the question of what belongs to the essence of the church, as God intended it to be, by identifying certain indicators of the essence of the church through a study of one of the central metaphors of the New Testament: the vine in the Gospel of John. Through structural analyses, commentary and metaphorical analyses, several indicators of unity as part of the essence of the church emerge in this metaphor. These indicators are the primacy (or authority) of Christ, trinitarian balance, equality, interdependence, inclusivity, growth and unity (in diversity).

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel poog om die volgende vraag te beantwoord: Wat behoort tot die essensie van kerkwees soos God dit bedoel het? Dit word gedoen deur sekere aanwysers van die essensie van kerkwees te identifiseer vanuit 'n studie van een van die essensiele metafore vir kerkwees in die Nuwe Testament, naamlik die Wynstok in die Evangelie van Johannes. Deur middel van struktuuranalise, kommentaar en metaforiese analise kom verskeie eenheidsaanwysers as deel van die essensie van kerkwees in hierdie metafoor na vore. Hierdie aanwysers is die hoer gesag (of outoriteit) van Christus, die balans van die Drie-eenheid, gelykheid, interafhanklikheid, inklusiwiteit, groei en eenheid (in diversiteit).

Introduction

We live in a world with many people and churches. We find countless denominations and independent churches on every continent. These churches have many differences. They include different buildings, styles of worship, leadership structures and contexts (Barrett, Kurian & Johnson 2001:16-18).

It is possible for churches to differ a lot. However, the essence of the church, that which makes the church God's church, should not change. This invariably leads one to ponder the question of what belongs to the essence of a church as God intended it to be. This article aims to identify certain indicators of the essence of the church by looking at one of the central metaphors of the New Testament: the vine in the Gospel of John.

Three matters are to be clarified from the outset:

- This article will only comment on unity as part of the essence of the church with regard to what one can learn about this subject from the metaphor of the vine in the Gospel of John. Therefore, it will not contain, or claim to contain, a complete description of the unity or of the essence of the church.

- Although John's Gospel does not use the word ekklesia, it does have a lot to say about ecclesiology.1 John's Gospel is both history and theology (Bauckham 2007; Holladay 2005:201203). Du Rand (1996:61) chooses to refer to it as a 'Theological Narrative'.

- This article uses an exegetical and linguistic review of a metaphor. Therefore, it will use a problem-orientated methodological approach, rather than an ideological-paradigmatic approach, with the text of the Bible as its primary basis of study.

Background to the Gospel of John

Introduction to the Gospel2

Scholars have described the Gospel of John as 'the most influential book of the New Testament' (Culpepper 1998:13). The reasons include that it is the only book in the New Testament to depict Jesus as the Logos, and how it has added to the doctrine of the Trinity, its description of the humanity and divinity of Jesus, as well as the fact that it contains more information about the Holy Spirit than any other writing in the New Testament (Culpepper ibid:13-14). Holladay (2005:191) writes that the Fourth Gospel's sheer capacity to engage readers has lifted it from its position as Fourth Gospel, whilst Brown (2003:26) describes the Gospel of John as one of the principal foundational documents of Christianity.

This article now turns to the background of this remarkable book of the New Testament. As Van der Watt (2000:14) rightly points out: 'The socio-historical framework within which a metaphor was originally created also plays an important role in the continued cognitive and emotive functioning of a metaphor'.

The Book of John as a Gospel

Scholars generally accept that the genre of the book of John is that of a gospel.3 Therefore, it is a combination of a historical narrative - in describing the life of Jesus - and theology since it gives us a unique insight into various theological themes because of its choice of material (Jn 21:25) and style of writing.

John 15 and the structure of the Gospel of John

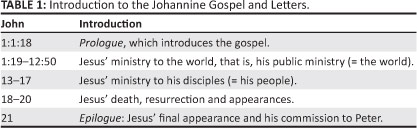

Scholars have proposed many structures for this Gospel (cf. Van der Watt 2007:12; Kostenberger 2004:vii; Brown 2003:298-310; Keener 2005:xi-xxiv; Moody Smith 1999:710; Stibbe 1993; Whitacre 1999:45-48; Carson 1991:105-108; Sloyan 1988; Beasley-Murray 1987:xci-xcii; Barret 1978:v-vi; Lindars 1972:70-73; Brown 1966:CXXXIIX). Some are extremely detailed and others less so. One example is that of Van der Watt (2007:12) in his Introduction to the Johannine Gospel and Letters, shown in Table 1.

In Table 1, it is clear that Van der Watt sees John 13:1-17:26, the section in which we find the metaphor of the vine, as a separate section of the Gospel (as do others). For Van der Watt (2007:12), it is 'Jesus' ministry to his disciples'. For Brown (2003:298-310), it is 'the last encounter' and is the first part of the 'Book of Glory'. Keener (2005:xvii-xxi) refers to it as the 'Farewell Discourse'.

When we look to the pericope, in which we find the metaphor of the vine, we note that Van der Watt (2000:31-54) sees John 15:1-8 as a pericope because all relate to one thing - the metaphor of the vine. Note that John 15:9-17 deals with love as the fruit of the vine and that John 15:18-27 deals with the notion that if the world hates Jesus (the vine), it will also hate his followers (its branches).

This article agrees with Van der Watt (2000:31-48) about where the pericope starts and ends.

The metaphor of the vine - John 15:1-8

Introduction to the metaphor

This article now focuses on the metaphor of the vine, which has been described as 'one of the most powerful descriptions of eternal life to which John is bearing witness' (Whitacre 1999:370) and 'one of the most memorable passages in the farewell speech' (cf. Stibbe 1993:161; Bultmann 1971:529).

This metaphor, should one accept it to be one, as this article does, 'is a complex one' (Minear 1960:42). Scholars have challenged even the figurative nature of these verses, as Van der Watt (2000:27-28) shows when he categorises the main opinions and their proponents - opinions that include a 'gleichnis', a 'parabel', 'imagery or bildrede', 'allegory', 'figure', 'symbolic speech', 'mashal' and finally 'metaphor'.4

Whether or not one should see John 15:1-8 as a pericope is also a matter for debate.5 This article agrees with Van der Watt (2000:28) in identifying John 15:1-8 as a metaphor, with John 15:9-17 dealing with love as the fruit of the vine and John 15:18-27 dealing with the fact that if the world hates Jesus (the vine) it will also hate his followers (the branches).

This is discussed in the structural analysis (Figure 1).

The words Έγώ είµι in verse 1 introduce a new pericope as a new Έγώ είµι saying. Furthermore, we find that verses 1 to 8 are a separate pericope. It uses the semantic and contextual cohesion that the use of the complex imagery of vine farming and the figurative use of semantically related words like vine, branches, pruning and fruit creates. Together they present a single but complex facet of reality in more or less one textual locality (Van der Watt 2000:28). Therefore, we need to make an introductory statement on the whole of this pericope: that µείνατε (έν έµοί) dominates these verses.

John 15:1-2 presents the metaphor (Kellum 2004:170) and contains two separate statements: that Jesus is the vine and that the Father is the vinedresser. This frames the whole metaphor from verse 2 to verse 8.

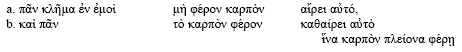

In verse 2, we have an antithetical parallelism that highlights the possible positive or negative consequences: if a branch abides in Jesus as vine or fails to do so. Verse 3 flows from this. It links to verse 2 because we find the idea of being clean or cleaned (καθαιρεί) in both.

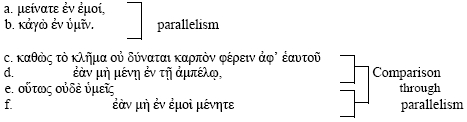

Verse 4 introducesthe refrain of these verses with the words µείνατε έν έµοί. The verse comprise a parallelism ('abide in me as I abkle in you') and then a compara tive ρarallelism that further describes the consequences of µείνατε έν έµοί.

Verse 5 introduces the second half of the metaphor by extending the metaphor to include the disciples ('I am the vine, you are the branches'). The verse continues with the first of three groups of consequential statements that flow from these words. We find one positive ('he that abides in me'), followed by a negative ('if one does not abide in me') and followed again by a positive ('if you abide in me').

Therefore, we see that verse 1 introduces and frames the extended metaphor, verses 2-4 form a unit as the first half of the metaphor, verses 5-7 form the second half of the metaphor by extending the metaphor and verse 8 glorifies the Father. This would be true if the disciples decide to listen to the words of Jesus because of the first and second halves of the extended metaphor.

Now that the structure of the argument in these verses has been established and a structural analysis has shown that it is a single and cohesive pericope, the commentary and metaphoric analysis of these verses follow.

Commentary on John 15:1-8

These verses form part of the final words of Jesus to his disciples that he spoke 'in the light of his impending betrayal and death' (Ball 1996:129; cf. Kostenberger 2004:11; Keener 2005:893-1066; Moody Smith 1999:262-308; Carson 1991:107; Barret 1978:470). Some refer to it as 'Farewell Discourses'6 that are 'narrative commentary on discipleship against the background of Jesus' death and resurrection with an emphasis on the unity motif' (Du Rand 1991:321).

When Carson (1991:510-524) comments on these verses, he begins by doing so under the heading 'the extended metaphor' related to vine farming. In this extended metaphor of John 15:1-8, we also find a certain 'mutuality in which Jesus [...] maintains the priority or primacy' (Smith 1995:146147), something that Ball (1996:131) has noticed. Ball points out that the first person ('I am') establishes and emphasises the dominance of Jesus' character in the metaphor.

Minear (1960:42) also sees Christ as central to this metaphor. Although interpreting this metaphor is complex for him, from reading these verses one can, at the very least, say that the central focus is the total dependence of the branches (the disciples) on the vine (Jesus Christ). This is true of many New Testament images of the church. Here also the 'Christological reality is absolutely basic to the ecclesiological reality' (Minear 1960:42). This article argues that the primacy of Jesus is the first indicator of unity as part of the essence of the church.

Vine imagery was extremely common7 in the Synoptic Gospels (Mt 21:23-41; Mk 12:1-9; Lk 20:9-16; Mt 20:1-16 and 21:28-32 and Lk 13:6-9; cf. Barret 1978:471; Keener 2005:988), as well as in the ancient world (cf. Brown 1966:669-672; Dodd 1968:411; Carson 1991:513; Van der Watt 2000:26-29; Kostenberger 2004:448-450; Whitacre 1999:371). However, John's use probably has an Old Testament background because of the frequency with which John refers to the Old Testament through allusion or reference, as well as the dominance of replacement as a motif in John's gospel - in this case, Jesus is the true vine whilst Israel is the vine.8 In other words, in Jesus' reference to himself as the true vine, he takes an image for Israel from the Old Testament9 and applies it to himself.

This, the last of John's syro sipi sayings (cf. Whitacre 1999:371) about Jesus, is the only one that has an 'additional assertion, and my Father is the gardener' (Carson 1991:513), or that is spoken differently where we have such an extended metaphor. Schnackenburg (1982:96) goes as far as to say that, compared to the other syro sipi sayings, this image, figuratively speaking, develops more powerfully.

The metaphor begins in verse 1 so that the emphasis falls clearly on Jesus10 as the vine and not on the Father as the gardener (Brown 1966:659). This again emphasises the primacy of Jesus, with the addition of if ddr|9ivf after the noun as the striking feature that emphasises itself (Schnackenburg 1982:97) and the vine that it describes.

The purpose of f ddr|9ivf seems to be the same as in John 4:23 and 6:32, where it also points to a certain qualitative character (Schnackenburg 1982:97) - to show that the name applies fully to Jesus as the vine (cf. Bultmann 1971:530-531).

However, it does not stop here. Jesus, as the true vine, replaces Israel in the Old Testament as a vine that God planted in the Promised Land. Therefore, the people of God are no longer associated with a territory (Whitacre 1999:372). Finally, the people of God are those who abide in11 the true vine - that is, they live in relationship to Jesus. Du Rand (1996:68-69) goes as far as to say that we learn about the development of the plot in the whole of John's Gospel through relationships of which the true vine (Jn 15) is an example.

Munzer (1978:225-226) comments on this (isrvaTS sv [remain in] in John 15 by pointing out that the root occurs 118 times in the New Testament, of which 40 times are in the Gospel of John, and that John's use of the term with regard to the believers' relationship to Christ resembles its use by Paul. According to Munzer (1978), in John 15 it refers specifically to:

the closest possible relationship between Christ and the believer [...] abiding in Christ makes a man Christ's property right down to the depths of his being. It is not confined to spiritual relationship [...] but means present experience of salvation. (pp. 225-226)

Anderson (2008) sees this 'abiding in' as proof that John's gospel here shows:

a first-order engagement with living christological content (abiding in Jesus - Jn 15:1-8) rather than a second-order learning of the 'right-answers' theologically (abiding in the teachings about Jesus - 2 Jn 9). (p. 344)

'Although the principal idea in this discourse is that of "abiding in Jesus" (vv. 4-7),12 the Father does not play a secondary part' (Schnackenburg 1982:97). As the gardener,13 his role is to prune the branches for better growth and cut away those branches that have died and do not bear any fruit (cf. Carson 1991:514). It is clear in the context that the vine appears here primarily as a fruit-producing plant and only secondarily as life-bearing (Schnackenburg ibid:98).

Verse 3 shows that the words of Jesus have cleansed the disciples and that this will remain true as long as they abide in him and listen to his revelatory words that contain Spirit and life (Jn 6:63; Schnackenburg 1982:98; cf. Carson 1991:515; Keener 2005:374-375). Therefore, 'abiding' is a condition for bearing fruit and for the perseverance of the disciples to stay in the vine (Keener 2005:998). We must point out that with Jesus as the vine and the Father as the gardener, the words of Jesus, which contain the Spirit (Jn 6:63), cleanses the disciples. Therefore, we see the whole of the Trinity playing a part in the metaphor, pointing to the indicator of trinitarian balance.

Verses 4 and 5 apply the metaphor more directly to the followers of Christ - they are the branches that need to abide in Jesus, the true vine (µείνατε έν έµοί; cf. Bultmann 1971:534536). Scholars contend that the way in which the phrase 'you in me and I in you' (verse 4) uses the έν is a 'reciprocal immanence formula' (Schnackenburg 1982:99) that expresses the intimate relationship between Christ and his disciples.14 It is also strikingly similar to the words of Jesus that we find in John 6:56.

These words introduce the theme of mutual indwelling (Köstenberger 2004:451; cf. Lindars 1972:489) and create a relationship. The use of έν shows this relationship and strengthens the point that without it the disciples, as branches, lose the ability to bear fruit because they depend on that relationship remaining intact (cf. Carson 1991:515): the disciples of Jesus cannot bear fruit except in a relationship with him (cf. Barret 1978:470-471; Carson ibid:514; Whitacre 1999:375). It does this in a fashion that is not moralistic, but as the basis of fruitful activity. Therefore, it emphasises the notion of unity between the vine and the branches (Schnackenburg 1982:99), as well as their interdependence. It is another indicator of unity.

In verse 5, another έγώ είµι statement (cf. Schnackenburg 1982:100) stresses the relationship between Jesus and his disciples. We should note that Jesus does say that any disciples are excluded from the vine. As we see throughout the metaphor, all who abide in the vine (that is, live in a relationship with Jesus) and bear fruit are part of the vine. Therefore, we see the indicator of inclusivity.

Verse 6 turns the positive statement in verse 5 on its head by stating the negative consequences15 of not 'abiding in' and not 'bearing fruit': it is cut off and burned - an image that reminds one of the judgement in John 12:31 and of Jerusalem as a vine in Ezekiel 15 (cf. Carson 1991:517; Whitacre 1999:376). One could even say that, if the branches do not grow, they will not bear fruit and they will die. This metaphor implies the indicator of growth.

Verses 7 and 8 swing to the positive16 side again and remind the readers that if they take these words to heart they will stay firm in their close relationship with Jesus, continue to bear fruit and, in so doing, glorify (cf. Bultmann 1971:539) the Father (Whitacre 1999:377; Barret 1978:475; Carson 1991:518). Again, this shows interdependence.

We need to say that John takes great pains to show that Jesus is the Spirit inspired (Jn 1:26-34) in the vine part of the metaphor and that the Father is also involved as the gardener.

Therefore, in a sense, we find the indicator of trinitarian balance17 presented in John's extended metaphor of the vine, something that Köstenberger (2009:241) also comments on in 'note the trinitarian theme'. Schnackenburg (1982:97), in turn, refers to this as 'a theocentric view'. Therefore, we find the indicator of trinitarian balance here: Father, Son and Spirit are all involved in their own unique ways.

By using this extended metaphor,18 John wants his readers to realise that being part of the vine has nothing to do with nationality. Jesus is the vine and all those (an indicator of inclusivity), who are in a right relationship with him, are incorporated into the vine as its branches (Carson 1991:514). Brown (1966) expresses it as:

[I]n presenting Jesus as the real vine, the Johannine writer may well have been thinking that God had finally rejected the unproductive vine of Judaism still surviving in the Synagogue. (p. 675)

This confirms the situation from which this gospel was born.19

John 14:20 introduces the theme of mutual indwelling, which we find in this metaphor, between Jesus and the believer when Jesus says 'you are in me and I am in you'. The metaphor of John 15:1-8 builds on this by saying that the branches (believers) get life from the vine20 and that the vine (Jesus) bears fruit through the branches. It is an indicator of interdependence and growth. The role of God the Father, as gardener, is to prune those that bear fruit to ensure more fruit and to cut away those that bear no fruit. This illustrates the fact that, for John, carrying fruit was part of faith in, and connection with, Jesus (Carson 1991:516-517).

Interestingly enough, it is exactly at this point that Smith (1995:136) asks the question of whether one should infer a theology of the church from John 15:1-8 in which church offices and hierarchy are of no importance because every believer, disciple and follower of Jesus must relate directly to him. This leads one to conclude immediately that, through this extended metaphor, John is saying that there is equality between branches within the church - the followers of Jesus who abide in him. It is an indicator of equality.

A closer look at the metaphorical language of John 15:1-8 follows.

Analysis of the metaphorical language in John 15:1-8

The metaphorical analysis uses the model that Van der Watt (2000) proposed as its basis. Consequently, there will not be many references to commentators or writers because:

- The commentary above includes these.

- The method is quite new. Therefore, one does not find a lot of work that applies it as Van der Watt (2000) has.

Analysis of John 15:1

a. Έγώ είµι ή άµπελος ή αληθινή

b. και ό πατήρ µου ό γεωργός έστιν.

This verse literally reads: 'I am the true vine, and my Father is the gardener'.

As Van der Watt (2000) explains:

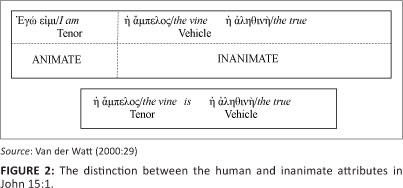

In the copulative metaphor Έγώ είµι ή άµπελος ή αληθινή [I am the true vine], incongruence exists between Έγώ [I (tenor)] and ή άµπελος [vine (vehicle)], since Έγώ [I] requires a noun associated with human attributes and vine a noun associated with inanimate attributes; this incongruence causes semantic tension. (p. 29)

Figure 2 shows the distinction between the human and inanimate attributes.

When one reads this on its own, one automatically asks oneself which of the attributes that are true of a 'vine' are also true of 'I' to warrant this connection? The reader has no way of answering this question and determining what this phrase is trying to say about Jesus. The interesting thing is that the context also does not answer the question because the comparative relation that this metaphor creates between I and vine does not develop it further (Van der Watt 2000):

The stated link between I and vine has another function. Although Jesus is the vine, the emphasis does not fall on the person of Jesus as such, in the sense that the context provides the reader with all kinds of indications of how qualities of the vine indeed expounds the personality of Jesus (as will be looked for when applying a metaphor theory which emphasizes semantic interaction between tenor and vehicle). (pp. 29-30)

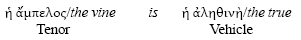

This metaphor simply functions as an introduction to the vine imagery and functions as a central alternative element within the broader image. The vehicle (true vine) in verse 1(a) contains no incongruities. It could simply be an indication that this vine is true when one compares it to another that might be false. It is only through its connection with I that vine becomes a metaphor (Van der Watt 2000:30). Therefore, it becomes part of a metaphorical expression and functions as an adjectival metaphor with the adjective (true) as the vehicle:

'In the context where vine is metaphorically related to Jesus, "true" qualitatively identifies this "vine" in contrast to all other vines' (Van der Watt 2000:30). One sees this as relation C in Figure 3. The adjective αληθινή, a common Johannine term, is associated with God (and Jesus) in the rest of John's Gospel (cf. Jn 1:14, 17; 3:33; 4:23-24; 7:28; 8:14, 26; 14:6, 17; 15:26; 16:13; 17:3, 17). The author used it to project divine qualities onto the vine. Therefore, it intensifies the qualitative description of the vine because Jesus is the vine (relation B in Figure 3) and the vine is true (relation C in Figure 3). One can illustrate these semantic interrelations as in Figure 3 (Van der Watt 2000-30-31).

Therefore, we see that I and true correspond semantically (relation A in Figure 3 above) as I is the tenor of this metaphor (Ί am the tme vine'). Consequently, some or οther quality of I determines true. Therefore, true as an adjective attributes certain specific qualities to the vine that I shares. 'These qualities are related to the divinely authentic and true as opposed to the inauthentic, in comparison to the divine' (Van der Watt 2000:31)

Nerertheless, the reader still has no clear indication as to why John compares Jesus to a vine and what one should make of Shis comparison. Therefore, She metaphor is still open and unspecified. Tie information the con text supplies should help the reader to find an answer to this question. By leaving this question unanswered, John succeeds in creating a sense of suspense and expectation (Van der Watt 2000:31).

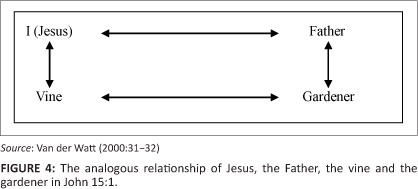

The article has now shown that the phrase, ό πατήρ µου ό γεωργός έστιν [my Father is the gardener] (Jn15:1b), is not incongruent if one takes it on its own. However, its figurative status is clear in this context. The copulative και [and] links 'my Father' directly to the preceding metaphor of the vine. John 15:2 confirms this further where we see that the Father prunes the branches that are έµοϊ [in me (Jesus)]. This confirms it as figurative language. As with 'I am the true vine', one cannot determine the exact semantic function of 'my Father is the gardener' from the local expression alone. However, the context somehow makes it easier to do so.

A particular image is beginning to unfold.

The relationship between Jesus and the Father is analogous to the relation between a vine and the gardener (Van der Watt 2000:31-32). John starts his gospel with Jesus receiving the Spirit at his baptism. This implies that, in Figure 4, the Spirit, the Son and the Father are involved. It is an indicator of trinitarian balance.21

Analysis of John 15:2

This verse literally reads: 'He cuts off every branch in me that bears no fruit, whilst every branch that does bear fruit he prunes so that it will be even more fruitful'.

As Van der Watt (2000) explains:

This antithetical parallelistic statement about the pruning of the branches has no apparent incongruence on a local level. However, the subject of the indicative verbs is the Father, and 'in me' refers to Jesus, which implies that the metaphorical application is continued, which was already constituted by the use of the phrases vine and gardener in verse 1. The reference to Jesus with the phrase 'in me' further links a person (animate) to the branches (inanimate). The Father's function as gardener is narrowed down by the context to the action of pruning and thus it becomes semantically more specified. (p. 32)

By creating a OTnnectkm between Faiher, Jesus, branches and By creating a connection between Father, Jesus, branches and pruning in this way, it defines clear contextual borders within which the metaphorical interpretation of these images should happen.

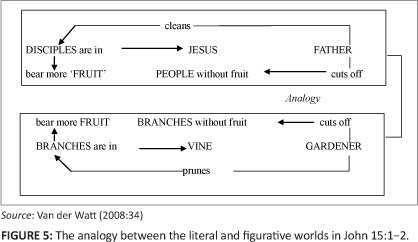

Therefore, in verses 1 and 2, John creates a multi-level basis of communication in which he compares Jesus with the vine, the disciples with the branches and the Father with a gardener. It is an indicator of interdependence.

He can now substitute vine with a personal reference to Jesus (έν έµοϊ: v. 2) in a sentence that uses vine farming terminology, and in which ή άµπελος instead of έν έµοϊ would probably have been more suitable had it not been figurative speech (Van der Watt 2000:03). Therefore, phrases like 'I am the vine', 'the Father is the gardener', and 'you are the branches' now have a clear meiaphoriral function. We need to interpret them on a literal and figurative level.

This means that, on a figurative level, one should replace vine, gardener or branch with Jesus, Father and disciples. Therefore, the implication is that the literal and figurative levels run parallel to each other, at least as far as the objects are concerned. We should replace, or identify, an object we find on the literal level with an object on the figurative level (Van der Watt 2000):

This should, therefore, be seen as a form of (metaphorical) substitution in which the literal phrases (vine, gardener, etc.) have the function of drawing the figurative objects (Jesus, Father, etc.) into a comparison, with objects related to vine farming and thus elicits the figurative applications which are indeed being made. (p. 33)

All of this happens through analogy. The connection of the vine to the branches is analogous to Jesus' relationship with his people, as is the gardener's pruning οf the branches with the action of the Father towards those who are in Jesus (Van der Watt 2000:33).

Analogy, as a stylistic feature, is especially important where we find an extended image - like that of the vine in John 15. Therefore, the relationship that the extended metaphor establishes between the figurative aspects of the image (vine-branches-gardener, etc.) is analogous to that of the literal aspects (Jesus-those who belong to him-God, etc.). This includes John's repetition of the word παν [every] as a literal indication of the inclusivity of the actions of the gardener and it illustrates the indicators of inclusivity and equality.

A possible schematic presentation (Figure 5) of this analogy follows (Van der Watt 2000:34).

This article has established the links between the figurative and the literal worlds. However, what exactly pruning or bearing fruit means remains unanswered. The reason is that in this extended metaphor the vine represents Jesus, the gardener represents the Father and the branches are the people in a positive or negative relationship with Jesus.

However, it is a different story with the verbs pruning and bearing fruit because nothing can substitute them. The same words occur on both the literal and figurative levels (Van der Watt 2000):

The Father prunes just as the gardener prunes. The use of the same verb in both these cases indicates where the point of analogy lies. By using pruning for the disciples, vine-farming language is used to create interaction between the world of branches and the lives of people. This seems to be the point where an important semantic transfer occurs. A point of similarity exists (i.e. something is cut away or cleaned), but the same verb also suggests a point of difference (the way in which the cutting away or cleansing functions, on literal and figurative levels respectively, is completely different). Metaphorically speaking, interaction takes place. By identifying the associated similarities (e.g. cleaning) the differences (e.g. branches and people are not cleaned in the same way) are also accentuated. In this way the verb pruning creates interaction (= creative movement of meaning) between the figurative and literal worlds respectively. (p. 34) the cutting away or cleansing functions, on literal and figurative levels respectively, is completely different). Metaphorically speaking, interaction takes place. By identifying the associated similarities (e.g. cleaning) the differences (e.g. branches and people are not cleaned in the same way) are also accentuate. In this way the verb pruning creates interaction (= creative movement of meaning) between the figurative and literal worlds respectively. (p. 34)

Seen in this light, the question of how one should understand the individual elements of verse 2 remains. What is t interaction between them? There is no clear indication as to what exactly κλήµα [branch], φέρον [bear], αίρει [cut], καθαίρει [prune] and τό καρτόν [fruit] refer to figuratively.

Although they are all part of extended metaphors, the reader is still only sure as to what the 'vine' and the 'gardener' (v. ) refer. Luckily, contextual information assists one to determine the answer. Verse 3 explains pruning (καθαίρει). In verse 6, the cutting away (αίρει) of branches receives attention, whilst verses 4-5 and 7 covers έν έµοί [in me]. Verse 5 explains κλήι [branch].

It seems that the rest of the context explains or elaborates on all the elements that were unclear in verse 2, except for τό καρπόν [fruit]. The context also covers this, but in a different way (Van der Watt 2000:35).

Therefore, John restricts the openness of the imagery that verse 2 created and limits the interpretation of these vers es (Van der Watt 2000):

It should, therefore, be noted that cohesion is created between t different phrases due to the shared imagery, which also implies that this 'natural cohesion' of the imagery forms the semantic basis on which the different facets of the figurative message are interrelated. Different phrases, semantically related on the basis of shared imagery, therefore, form an interpretative network in which this inter-relatedness serves to specify the meaning of the phrases. (p. 35)

Analysis of John 15:3

ήδη ύµεΐς καθαροί έστε δια τόν λόγον δν λελάληκα ύµΐν. This verse literally reads: 'You are already clean because of the word I have spoken to you'.

As Van der Watt (2000) explains, when one reads the verse it is clear that, on the surface, it:

... does not seem to reflect the idea of 'vine farming', except for the subtle word play between καθαίρει [pruning] (v. 2) and καθαροί [clean] (v. 3). In this way verse 3 is shown to be part of the larger metaphorical network, although καθαροί is (seemingly) used in a double sense in these two verses, namely in the sense of pruning in order to clean (15:2), but also merely in the sense of being purified or cleansed (15:3; see 13:10,11). (p. 35)

The question now becomes how exactly should one understand the function of verse 3 against the background of the metaphorical network of which it is a part. This verse elaborates on how the pruning, or cleansing, of ύµεΐς [you] occurs. It is δια τόν λόγον [through the word]. The phrase τόν λόγον has the function of cleaning a person (ύµεΐς) to ensure that the person it has cleaned bears more fruit, as is the case when one prunes a branch. Therefore, we see(Van der Watt 2OOO):

... elements of the literal world [...] substituted with the elements of the figurative world. The reference to the cause is actually an addition and extension to the image of verse 2. The writer feels himself free to extend the image in his own way in order to communicate a specific aspect of his message. (p. 36)

Whilst staying within the boundaries of the image of vine farming, John explains new dimensions of his message by extending the image he created in verses 1 and 2.

What is gradually becoming clear is that the writer moves from the figurative to the literal with ease; he does not feel himself bound to the imagery in the sense that he should only speak in terms of that. He freely mixes elements of the imagery with elements of the literal application within the same sentence. This gives an indication of how the author wants the figure to be interpreted, for instance, the pruning action is not just any action. It should be seen as the way in which the work of Jesus is influencing the lives of his disciples in order to bear more fruit. (Van der Watt 2000:36)

Analysis of John 15:4

This verse reads: 'Remain in me, and I will remain in you. As a branch cannot bear fruit by itself except if it remains in the vine, you cannot bear fruit unless you remain in me'.

With this verse, the interpretation becomes quite complicated. However, Van der Watt (2000:37-39) interprets this verse masterfully:

How the expression of immanence in the phrase: Remain in me and I will remain in you, should be understood, is a well-known problem in this Gospel. In the immediate context, the opening metaphor (I am the vine) as well as the remark in verse 2 (every branch who remains in me) suggests a figurative reading, which means that 'you' is associated with the branches and 'I' with the vine. However, the verse illustrates an interesting aspect about applying images. It violates the limits of the imagery in order to express their messages to the full. (pp. 37-39)

It shows the importance of the message to the formal restrictions of the imagery itself. With regard to the image of the vine-branches, it seems to be impossible for the vine to stay in the branches because the smaller branches can stay in the larger vine. However, the larger vine cannot logically stay in the smaller branches.

With regard to the inanimate image of the vine, the expression in verses 4a-4b does seem impossible. The substitution of the inanimate vine and branches with the animate Jesus and the disciples respectively ascribes personal qualities to the inanimate vine.

This makes the expression of immanence more plausible. For example, the influence of Jesus might be on his disciples and his disciples might live in the sphere of that influence. This implies 'immanence'. In verses 4c-4f, the expression grounds the expression: 'Remain in me, and I will remain in you'. Without staying in Jesus, the disciples will not be able to bear fruit. The relations between the different objects (vine, branches and fruit), and what happens to them, create the logic of the imagery. As Neyrey (2007:254) expresses it: 'It makes horticultural sense to state that branches are "in" the vine and the vine "in" the branches, but Jesus' remarks is not spatial, but relational'.

Verses 4c and 4d describe a basic relationship between different objects. A branch stands in a specific relation to the vine - it stays in the vine. This is (logically) a prerequisite for the branch if it wants to bear fruit. If one reasons logically, it cannot bear fruit by itself. Therefore, it states the importance of the vine for both the branch and the fruit.

Verses 4e-f substitute the objects of this logical imagery frequently. You (the disciples) stand in a specific relation to me (Jesus) - they stay in the vine. This is a prerequisite for the disciples if they want to bear fruit. They cannot bear fruit out of themselves. They substitute the objects (Jesus for the vine and the disciples for its branches), but maintain (stay in, bear fruit) the logical relations. This reminds us of the indicators of interdependence and mutual edification.

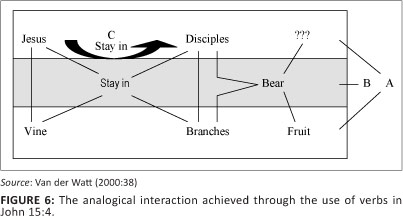

In Figure 6, Van der Watt (2000:38) illustrates the important function of what he calls analogical interaction through the gospel writer's use of verbs.

We see clearly how John uses substitution - a replacement on the figurative side - between Jesus and the vine, as well as the disciples and the branches (A in Figure 6), whilst the verbs ('stay in' and 'bear') remain unchanged regardless of whether he uses them on a literal or figurative level. As Van der Watt (2000) explains:

The disciples have to remain in Jesus as the branches remain in the vine, since both the branches and the disciples must bear fruit. However, the way in which the branches remain in the vine or bear fruit is not the same as the way in which the disciples remain in Jesus or bear fruit. Although the same words (stay or bear) are used, they differ semantically when used with the different objects. (p. 38)

Analysis of John 15:5

a. έγώ είµι ή άµπελος,

b. ύµεΐς τα κλήµατα.

c. ό µένων έν έµοί κάγώ έν αύτω

d. ούτος φέρει καρπόν πολύν,

e. δτι χωρίς έµοΰ ού δύνασθε ποιεΐν ούδέν.

This verse reads: 'I am the vine, you are the branches, He who remains in me and I in him will bear much fruit; because apart from me you can do nothing'.

The first part of this verse repeats the basic metaphor from John 15:1, but without the adjective ή αληθινή [the true].

However, John's purpose was not simply to repeat the metaphor, as Van der Watt 2000 explains:

... here a shift in emphasis takes place in relation to the basic metaphor of Jesus being the vine. In verse 1 the vine is mentioned in connection with the gardener (v. 1b) [...] the emphasis [here is] on the devastating consequences for the branches if they do not stay in the vine. (pp. 39-40)

When we turn our attention to verse 5c (ό µένων έν έµοί κάγώ έν αύτω), we see this is almost a word for word repetition of verse 4a-b. On the surface, it is a literal statement. However, in its context it becomes an extension of the vine farming metaphor. Verse 5d, in turn, is figurative with its explicit reference to 'vine farming', whereas verse 5e is a literal statement again and echoes verse 4e (Van der Watt 2000:40).

Therefore, this verse underlines and emphasises the dependence of the branches on the vine. However, from this verse and indeed from the whole metaphor, one could also argue that the author is trying to make a strong point about the unity between the vine and the branches and, by implication, the branches with each other because they are part of one vine.

From this, one could reason that the metaphor gives us unity as an indicator of the essence of the followers of Christ. One could even go further and say that this unity is actually unity in diversity because you have one vine with many branches of which no two are the same. However, John's metaphor does not state this explicitly.

Analysis of John 15:6

a. έαν µή τις µένη έν έµοί,

b. έβλήθη εξω ώς τό κλήµα

c. καί έξηράνθη

d. καί συνάγουσιν αύτα

e. καί είς τό πΰρ βάλλουσιν

f. καί καίεται.

This verse reads: 'If anyone does not remain in me, he is like a branch that is thrown away and withers, such branches are picked up, thrown into the fire and burned'.

In this verse, John describes what happens to branches that do not remain in Jesus as the vine and do not bear any fruit. Therefore, this verse refers to the results of pruning that John mentioned in verse 2. However, the branches are merely cut off in verse 2. They are also thrown away in verse 6. Van der Watt (2000:41) is correct in pointing out that an 'important question is whether a figurative counterpart should be found for each and every one of the actions mentioned in verse 6'. Van der Watt (ibid) also answers this question by saying:

This does not seem to be the intention here [... ] It seems as if the author wants to create a specific atmosphere of destruction by giving such a climactic description of what happens to the branches. The description should be regarded as a unit (cf. the progressive use of καί, as well as the vocabulary of related terms), and should not be interpreted allegorically, or in detail, since no indication is given by the author of how this should be done in the narrower or broader context. The focus is on the ultimate destruction as a result of alienation from Christ. Not particulars, but the general message, should be applied comparatively, which means that the precise detailed explication of the destruction should not be attempted. (p. 41)

At this point it makes sense to point out that, throughout the extended vine metaphor, the one thing that one may assume about or that lies under the surface of the metaphor is that of growth. The branches cannot bear fruit and there cannot be branches in the vine if there is no growth. Therefore, the indicator of growth in the metaphor of the body is also present in the metaphor of the vine.

Analysis of John 15:7

a. έαν µείνητε έν έµοί

b. καί τα ρήµατά µου έν ύµΐν µείνη,

c. δ έαν θέλητε αίτήσασθε,

d. καί γενήσεται ύµΐν.

This verse reads: 'If you remain in me and my words remain in you, ask whatever you wish, and it will be given to you'.

Verse 7a, έαν µείνητε έν έµοί [if you stay in me], forms an antithetical parallelism to verse 6a and it echoes the µένω έν [stay in] sections in the rest of John 15:1-8 (Van der Watt 2000:41-42). In these verses, John replaces Jesus' words with the implication that Jesus is present in the disciples through his words. Therefore (Van der Watt 2000):

... if the words of Jesus are in you, you will be guided by them. Jesus has a definite influence on the disciples in the sense that their wishes (7c-7e) and their actions (fruit) are adapted to and changes according to the will of God. In terms of the imagery τα ρήµατά (words) can be seen as a way by means of which the vine or Jesus influences the branches, which of course makes the incongruent reference of the vine remaining in the branches even more intelligible. (p. 42)

Analysis of John 15:8

a. έν τούτω έδοξάσθη ό πατήρ µου,

b. ίνα καρπόν πολύν φέρητε

c. καί γένησθε έµοί µαθηταί.

In this verse, John writes: 'This is to my Father's glory, that you bear much fruit, showing yourself to be my disciples'. One sees that '[n]o new metaphors are to be found here. What is said here, is echoed in the rest of the context' (Van der Watt 2000:42).

In short, in these verses (Van der Watt 2000):

John linked up with a general and well-known agricultural phenomenon in those days. The themes he metaphorizes are well described in ancient literature. Bearing fruit was the purpose of vine farming, pruning was done twice a season and was imperative for a good harvest and the gardener was important for taking care of the vine as he was was emotionally involved with what happened with the harvest. John even uses the idea that the branches, which were cut off, were burnt. The impression, which is left, is that this was a well-cared-for vine which belonged to a family, because the Father is the Gardener. The purpose of his care is fruit. (p. 44)

The theme of unity in the Gospel of John

This article would be remiss if it did not emphasise once more the point that has already been made in the commentary on the metaphor of the vine - that of unity.

The theme of unity is clear, especially through the motif of µείνατε έν [abiding in] (cf. Barret 1978:470). Some scholars feel that this 'abiding' reflects something of the Deuteronomic emphasis (cf. Dt 10:20; 11:22; 13:4; 30:20) on cleaving to the Lord, albeit with a much greater sense of union because the Greek term John 15 used has a much broader function (Keener 2005:999).

The image we find in John 15 is probably a development of John 14:2-3, which describes the believer as the dwelling place of the Father, the Son and the Paraclete (again, we find a trinitarian accent). With regard to the vine, 'abide' refers to 'complete and continued dependence for the Christian life on the indwelling Christ' (Keener 2005:999).

This image is symbolic of, for example, Jesus supplanting Israel as the vine (cf. Bühner 1997:217). It is also organic - and in this organic sense, it is close to Paul's use of the body as a metaphor for the church in 1 Corinthians 12, Romans 12 and Ephesians 4 (Keener 2005:999). It is an interesting remark if one keeps in mind the metaphor of the body, which is closely related to that of the vine.

The organic union that the image of 'abiding in the vine' establishes is extremely effective. It makes the nature and depth of the relationship between Christ and his followers, as well as the relationship of the followers with each other, clear. By applying the metaphor in the verses that follow the metaphor, we see that if one rebels against love, we endanger the health of the other branches. It might require removal from the community, that is, mutual dependence (Keener 2005:1000).

Unity is also an extremely important and recurring theme in the whole of the Gospel of John. John speaks of the one fold of sheep (Jn 10:16), the gathering together as one of the children of God (Jn 11:52), and the prayer that those who reach faith in Christ might be one as Jesus and the Father are one (Jn 17:11, 21-23).

Scholars have established the importance of unity in this Gospel (cf. Brown 1966:759, 769-771, 774-777; Dodd 1968:187-200; Van der Watt 2000:353-354, 438-439; Neyrey 2007:283-284 and 286-287). For example, Dunn (2005:128129) writes on John 17:20-23 that:

Jesus does pray for the unity of believers, which again speaks of community, but even here the unity John has in mind is comparable to the unity of the Father and Son and is both rooted in and dependent on the individual believer's union with Jesus. (pp. 128-129; italics added)

We see this unity in the metaphor of the vine and in the whole of John's Gospel. Therefore, it must be part of the essence of the Christian community - and a relationship with Christ is what establishes it. This unity, as we see in the verses that follow this metaphor, carries the fruit of love (Smith 1995:145).

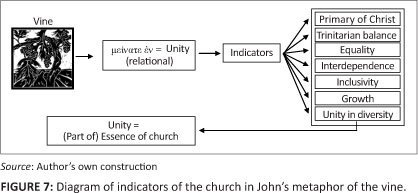

Consequently, unity in the metaphor of the vine is, in the words of Jesus, ¡isívaxs sv spot [abiding in me]. The unity is relational and this unity comes to the fore in the different characteristics attributed to the vine. This article calls them indicators.

Results of the study of John 15:1-8

This article's structural analyses, commentary and metaphorical analyses,22 have shown that several indicators of unity, as part of the essence of the church, emerge in the metaphor of the vine and the branches.

These indicators are (in no specific order):

- The primacy (or authority) of Christ. Jesus is central to the metaphor. If the branches do not abide in him, they are cut off. He determines the identity of the vine as the true vine.

- Trinitarian balance. In this metaphor, we see that the Father, the Son and the Spirit are one, by implication, because Jesus was filled by the Spirit at his baptism. We see, in John 3:34, that it is through the Spirit that the words of Jesus cleanse the branches. Later, the Spirit is also given to the disciples, that is, the branches (in Jn 20:22). They are all part of the metaphor, each in their own unique way.

- Equality. All branches linked to the vine are equal. No branch is singled out in anyway as being bigger or better, and all branches are called to do the same: abide in the vine and bear fruit, and submit to being pruned.

- Interdependence. The branches depend on the vine and both depend on the Father who tends to the vine.

- Inclusivity. All who abide in the vine and bear fruit are part of the vine. It excludes nobody.

- Growth. The branches receive life from abiding in the vine and, through this, bear fruit. Growth of the individual branches of a vine, as well as in the number of branches, is also something universally true of vines.

- Unity (in diversity). Although these indicators characterise unity as part of the essence of the church, the diversity of unique and different branches that abide in the same vine leads to unity in diversity. They also show this unity.

It is possible to draw a diagram (Figure 7), using this summary, which contains the insights we have gained from a better understanding of the metaphor of the vine.

In this diagram, we can see, from the metaphor of the vine in John 15, that unity is central to, and part of, the essence of the church (as a collective of the disciples and/or followers of Christ). 'Abiding in Christ' establishes this unity. It is a relational unity, coloured in a rainbow of seven indicators.

Conclusion

The metaphor of the vine, in John 15:1-8, does contain indicators of the essence of the church. If the indicators are missing, it would cause any church to cease being a church. It will become just another man-made institution because these indicators belong to the essence of the church as God intended it to be.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Aland, B., Aland, K., Black, M., Martini, C., Metzger, B. & Wikgren, A., [c1979] 1993, The Greek New Testament, 4th edn., United Bible Societies, Frankfurt. [ Links ]

Anderson, P., 2008, 'On guessing points and naming stars: Epistemological origins of John's Christological tensions', in R. Bauckham & C. Mosser (eds.), The Gospel of John and Christian Theology, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI. [ Links ]

Ball, D., 1996, 'I Am' in John's Gospel: Literary Function, Background and Theological Implications, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Barret, C., 1978, The Gospel according to St John: An introduction with commentary and notes on the Greek text, 2nd edn., SPCK, London. [ Links ]

Barrett, D., Kurian, G. & Johnson, T., 2001, World Christian Encyclopedia: A comparative survey of churches and religions in the modern world, Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Bauckham, R., 2007, 'Historiographical characteristics of the Gospel of John', New Testament Studies 53, 17-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0028688507000021 [ Links ]

Beasley-Murray, G., 1987, John, Word Biblical Commentary, vol. 36, A. Hubbard & G. Barker (eds.), Word Books, Waco, Texas. [ Links ]

Brown, R., 1966, The Gospel according to John (I-XII, XIII-XXI), Anchor Bible, vol. 29&29A, W. Albright & D. Freedman (eds.), Doubleday, Garden City, New York. [ Links ]

Brown, R., 2003, An introduction to the Gospel of John, Doubleday, New York. [ Links ]

Buhner, J., 1997, 'The exegesis of the Johannine "I-Am" sayings', in J. Ashton (ed.), The interpretation of John, T&T Clark, Edinburgh. PMid:9296279 [ Links ]

Bultmann, R., 1971, The Gospel of John, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Burridge, R., 1992, What are the Gospels? A comparison with Graeco-Roman biography, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Burridge, R., 2007, Imitating Jesus: An inclusive approach to the New Testament ethics, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Carson, D., 1991, The Gospel according to John, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Cassidy, R., 1992, John's Gospel in new perspective, Orbis Books, New York. [ Links ]

Culpepper, R., 1998, The Gospel and Letters of John, Abingdon Press, Nashville. PMCid:PMC2277720 [ Links ]

Culpepper, R., 2009, 'The quest for the church in the Gospel of John', Interpretation 63(4), 341-355. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002096430906300402 [ Links ]

DeSilva, D., 2004, An introduction to the New Testament: Contexts, methods and ministry formation, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, Illinois. [ Links ]

Dodd, C., 1968, The interpretation of the Fourth Gospel, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Dunn, J., 2005, Unity in diversity in the New Testament: An inquiry into the character of earliest Christianity, SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Du Rand, J., 1991, 'Perspectives on Johannine discipleship according to the Farewell Discourses', Neotestamentica 25(2), 311-326. [ Links ]

Du Rand, J., 1996, 'Repetitions and variations - Experiencing the power of the Gospel of John as literary symphony', Neotestamentica 30(1), 59-70. [ Links ]

Holladay, C., 2005, A critical introduction to the New Testament: Interpreting the message and meaning of Jesus Christ, Abingdon Press, Nashville. [ Links ]

Keener, C., 2005, The Gospel of John: A commentary, vol. 1&2, Hendrickson Publishers, Massachusetts. [ Links ]

Kellum, J., 2004, The unity of the Farewell Discourse: The literary integrity of John 13:31-16:33, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Kostenberger, A., 2004, John, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Kostenberger, A., 2009, A theology of John's Gospel and Letters, Zondervan, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Kümmel, W., 1975, Introduction to the New Testament, SCM Press, London. [ Links ]

Kysar, R., 1986, John, Augsburg Commentary on the New Testament, Augsburg Publishing House, Minneapolis, Minnesota. [ Links ]

Lindars, B., 1972, The Gospel of John, Marshall, Morgan & Scott, London. PMid:4647225 [ Links ]

Minear, P., 1960, Images of the church in the New Testament, Westminster Press, Philadelphia. [ Links ]

Moody Smith, D., 1999, John, Abingdon Press, Nashville. [ Links ]

Munzer, K., 1978, 'Remain', in C. Brown (ed.), The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, Volume 3: Pri-Z, pp. 223-226, Paternoster Press, Exeter. [ Links ]

Neyrey, J., 2007, The Gospel of John, The New Cambridge Bible Commentary, Cambridge University Press, New York. [ Links ]

Ringe, S., 1999, Wisdom's Friends, Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville. PMCid:PMC2144100 [ Links ]

Schnackenburg, R., 1982, The Gospel according to St John, vol. 3, Burns & Oates, London. [ Links ]

Sloyan, G., 1988, John. Interpretation: A Bible commentary for teaching and preaching, John Knox Press, Atlanta. [ Links ]

Smith, D., 1995, The theology of the Gospel of John, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511819865 [ Links ]

Stibbe, M., 1993, John, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, G., 1997, 'Towards a theological understanding of Johannine discipleship', Neotestamentica 31(2), 339-360. [ Links ]

Van der Watt, J., 2000, Family of the King: Dynamics of metaphor in the gospel according to John, Brill, Leiden. PMCid:PMC1852400 [ Links ]

Van der Watt, J., 2007, An introduction to the Johannine Gospel and Letters, T&T Clark Approaches to Biblical Studies, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Whitacre, R., 1999, John, InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Johann Fourie

PO Box 4467, Tzaneen 0850, South Africa

johann@dinamus.co.za

Received: 02 Aug. 2012

Accepted: 22 June 2011

Published: 26 Sept. 2013

1.Du Rand (1991:322) points out that the way John's gospel pictures discipleship 'contributes to a new model of ecclesiology'. Köstenberger (2009:481) argues - an argument that this article supports - that the Fourth Gospel contains 'corporate metaphors for Jesus' messianic community, such as "flock" (Jn 10) or "the vine" (Jn 15)'.

2.This article rests on the shoulders of work that various scholars have done. These include, amongst others, Holladay's introductions to the New Testament (2005:190-224, 303-332, 348-369, 392-408 & 409-419), DeSilva (2004:37-193, 391-448, 555-639 & 690-732), and Kümmel (1975:188-246, 252-254, 269-278, 305-319, 335-347 & 350-365). With specific reference to the Gospel of John, one needs to add the Introduction on the Gospel of John by Brown (2003). In providing a background to the Gospel of John, this article will not try to find out anything new. It will only summarise current insights in order to ensure effective exegetical results..

3.What are the Gospels? A Comparison with Graeco-Roman Biography by Burridge (1992) discusses this in-depth. See also Köstenberger (2009:104), Van der Watt (2007:1), Neyrey (2007:1), Culpepper (1998:13), Cassidy (1992:1), Kysar (1986:11), Kümmel (1975:200) and Dodd (1968:3).

4.Stibbe (1993:162) adds to this list by calling John 15:1-11 'the paroimia, the symbolic word-picture'.

5.See, amongst others, Whitacre (1999:371-380) who sees it as an extended metaphor (but only Jn 15:1-6 with Jn 15:7-17 as its application); Carson (1991:510-524) who shares the opinion of this article that the extended metaphor occurs in John 15:1-8, but sees John 15:9-16 (not 17) as the 'unpacking' of the metaphor; Moody Smith (1999:279) who simply comments that John 15:1-17 is a unit that contains the 'allegory' of the vine; Barret (1978:470-478) who follows this by seeing John 15:1-17 as a pericope that deals with the 'symbolism' of the vine; and Kostenberger (2004:448-509) who shares the opinion of treating John 15:1-17 as a unit.

6.Burridge (2007:301) refers to these Farewell Discourses as 'an extended meditation on the unity and divine love between Jesus and his Father in the Spirit, as it applies to his disciples'. Van der Merwe (1997:344) points out that one cannot understand these words, which he spoke in the light of his imminent departure, fully unless one remembers where Jesus came from (that is, the Father), what he accomplished (as John's Gospel shows), and where he is going (that is, back to the Father).

7.See Keener (2005:993): 'not completely unexpected'.

8.See, amongst others, Psalms 80:9-16; Isaiah 5:1-7; 27:2ff.; Jeremiah 2:21; 12:10ff.; Ezekiel 15:1-8; 17:1-21; 19:10-14 and Hosea 10:1-2. See Barret (1978:470-471), Kostenberger (2004:449-450) and Keener (2005:990-993) for an overview of the possibilities of the background being the Old Testament (Jewish), New Testament (Christian) or Hellenistic (or even a combination of them).

9.See chapter 1 ad loc.

10.See Ball (1996:131): 'In the image of the vine as well as in the use of the first person [...] the dominance of Jesus [...] is again emphasized'.

11.Stibbe (1993:162) believes that remaining together, with fruit bearing, are the two main motifs of the imagery in John 15:1-11. Culpepper (2009:344) writes: 'Abiding in Christ and the promise of Christ's abiding in his followers is only possible in the church'.

12.See Keener (2005:998): '(µένω and cognates) appears eleven times in 15:4-16, dominating the theology'. There is more on this later in this chapter. See also Whitacre (1999:371) and Carson (1991:514).

13.See Carson (1991:514): 'As in Psalm 80, God plants and cultivates the vine'.

14.Carson (1991:516) points out that we can read µείνατε έν έµοί, κάγώ έν ύµΐν, in verse 4, in one of three ways: (1) as conditional - if you remain in me, I will remain in you, (2) as comparative - remain in me, as I remain in you, or (3) as a mutual imperative - let us both remain in each other.

15.See Bultmann (1971:538): 'Alongside the promise stands the threat'.

16.See Bultmann (1971:538): 'After the threat comes a further promise'.

17.This article uses this term for want of a better one, albeit a dogmatic one, to refer to the balance between the involvement of the Father, the Son and the Spirit (in the church).

18.Kysar (1986:236) refers to it as a 'more developed metaphor'.

19.See Kysar (1986:236): 'Christ is God's servant who stands in the place of Israel. This was possibly the original setting for the metaphor in the life of the Johannine community'.

20.Brown (1966:660) points out that this is one of the main points of this 'allegorical parable', as he chooses to refer to it.

21.This article uses this term for want of a better one, albeit a dogmatic one, when it refers to the balance between the involvement of the Father, the Son and the Spirit (in the church).

22.Ringe (1999:5-8) believes that one cannot form a view of Johannine ecclesiology if one does not take his metaphors seriously because John's ecclesiology is metaphoric.