Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

In die Skriflig

versión On-line ISSN 2305-0853

versión impresa ISSN 1018-6441

In Skriflig (Online) vol.47 no.1 Pretoria ene. 2013

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Revelation 1:7 - A roadmap of God's τέλος for his creation

Openbaring 1:7 - 'n Padkaart van God se eskatologiese τέλος vir sy skepping

Kobus de Smidt

Department of New Testament, Auckland Park Theological Seminary, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Revelation 1:7 points to an anticipated final appearance of Jesus at the consummation. This κηρύσσω developed from the late Jewish apocalyptic eschatology. This apocalyptic end time dawned with Jesus. The present time is thus simultaneously the end time, though the consummation is still in the future. As Jesus appeared on earth with his resurrection, so will he appear at the consummation - his resurrection appearance is a simile of his appearance at the consummation. He will appear in a corporeal form. The writer encourages the second-generation marginalised Christians. The Roman emperor is not the victor - Jesus is the axis mundi of God's final purpose for his creation. The final appearance of Jesus will bring redemption for the believers and mourning for the unbelievers. The κηρύσσω of Revelation 1:7 is diametrically the opposite of the chiliasts. The country of Israel and her present inhabitants have no eschatological role to fulfil at the consummation.

OPSOMMING

Openbaring 1:7 dui op 'n geantisipeerde finale verskyning van Jesus met die voleinding. Hierdie κηρύσσω het uit die Joodse laat-apokaliptiese eskatologie ontwikkel. Die apokaliptiese eindtyd het met Jesus se opstanding plaasgevind en die Nuwe-Testamentiese hede is dus alreeds die eindtyd. Die voleinding is egter nog in die toekoms. Jesus se verskyning met sy opstanding is 'n metafoor vir sy koms by die voleinding. Hy sal liggaamlik verskyn. Die skrywer bemoedig die gemarginaliseerde tweede generasie Christene. Die Romeinse keiser is nie die oorwinnaar nie - Jesus is die axis mundi van God se finale plan vir sy skepping. Die finale verskyning van Jesus sal vir die gelowiges ewige verlossing bewerk, maar die ongelowiges sal in rou gedompel word. Die κηρύσσω van Openbaring 1:7 is die teenoorgestelde van die standpunt van die chiliasme. Die land en huidige volk van Israel vervul geen eskatologiese rol by die voleinding nie.

Introduction

The word eschatology is a combination of two Greek words: ἔσχατος [the last thing] and λόγος [teaching, word]. In a restricted sense, it is a discourse about the last things, with specific reference to the consummation and events directly associated with it (Du Rand 2007:20; Bauckham 1996:333; Aune 1992:594). It was first coined in the early 19th century as a technical term in German theology (Greshake 2005:489).

This article focuses on a component of the eschatology of Revelation, namely Revelation 1:7. The purpose of this article is to indicate that Revelation 1:7 is a metanarrative of God's τέλος for his creation. The κηρύσσω of Revelation 1:7 exists 'above' the text as an omega point - a climax of the transition of the historical to the supra-historical in Revelation which is a component of God's τέλος.

Although the term  ἔσχατος does not appear in Revelation 1:7, it is found in six instances in Revelation (ἔσχατος, Rv 1:17; 2:8; 22:13; έσχατα, Rv 2:19; ἐσχατα, Rv 15:1; ἐσχατων, Rv 21:19; Balz & Schneider 1991:61). Various researchers agree that the whole of Revelation has an eschatological motif (Coetzee 1990:253; Schrage 1988:332).

ἔσχατος does not appear in Revelation 1:7, it is found in six instances in Revelation (ἔσχατος, Rv 1:17; 2:8; 22:13; έσχατα, Rv 2:19; ἐσχατα, Rv 15:1; ἐσχατων, Rv 21:19; Balz & Schneider 1991:61). Various researchers agree that the whole of Revelation has an eschatological motif (Coetzee 1990:253; Schrage 1988:332).

The development of the New Testament eschatology and Revelation 1:7 is briefly formulated from the pre-Christian apocalyptic eschatology (Bruce 1986:47; Rowley 1980:181).

The development of the eschatology of the New Testament from the pre-Christian apocalyptic eschatology

According to various scholars (Du Rand 2007:21; Boshoff 2001:570; Bauckham 1996:333; Aune 1992:595), the best way to understand the key concepts of the New Testament eschatology is to interpret them in the light of the future hopes of late Judaism, namely the apocalyptic eschatology which forms the matrix of early Christian eschatology (Kraybill 2010:42, 44; Bauckham 1993:148). Jewish apocalypses were orientated towards the future only (Scott 2008:294). They conceptualised a restoration of primal conditions rather than an early new or utopian mode of existence (Wright 2008:106; Aune ibid).

Pre-Christian apocalyptic eschatology looked forward to an imminent irruption of God into the old order and the establishment of a new creation (Wright 2008:106; Aune 1992:595; Du Rand 1991:590; Collins 1979:61). The process whereby Jewish eschatology was transformed, began with Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus certainly stands within the framework of early Jewish eschatology, but he introduced a new perspective which was inherited and broadened by his followers after his death and resurrection (Aune ibid:597). Old Testament apocalyptic expectations become, in a way, present reality for the New Testament. The 'last days' of the prophets have arrived. God's new creation has dawned in this old order.

One of the apocalyptic theses for New Testament eschatology is the dialectic bond between the already and the not yet - to preserve the theological unity of God's redemptive work in the past, present and future (Kraybill 2010: 44-45; Wright 2008:127; Boshoff 2001:572; Petersen 1992:579). It has both an already - a realised or accomplished (the Christ event), and a not yet - a future reality with an imminent character (Wright 2010:77; Borg & Wright 2000:203).

The centre of divine history (Day of YHWH) has, by implication, already been reached in Jesus Christ. Thus the present time is already the end time, although the end itself must still be achieved (Scott 2008:294). Christian eschatology provides a context for a personal as well as a cosmic dimension (Wright 2010:77; Greshake 2005:490; Aune 1992:594). It is more about the purpose of history than about the terminus of history (Kraybill 2010:180).

The social context of the readers

Revelation was written for the Christians in western Asia Minor during the Domitian period 81-96 CE, terminus ad quem (Duling 2003:446). As second-generation Christians they were a marginalised group. Because of their religious convictions, they suffered under both Judaism and the Roman society (Kraybill 2010:32; Slater 1998:242; DeSilva 1992:378). They survived the threats of the Nero regime, the death of the apostolic generation, the most eloquent tension between church and state, sporadic persecution and major natural disasters. In his pastoral letter to the churches (Rv 1:4a), the author's objective is to help his communitas to discern the superior authority of Christ behind the throne of Caesar. God is in control of history and the world (Tenney 2004:309, 314; Duling ibid:465).

Revelation 1:7 is couched in the language of an oppressed people who, to a great extent, became an underground movement (religio illicita) according to Pliny's letter (Tenney 2004:341, 344). Although it speaks of a world yet to come, much of its imagery is drawn from the civilisation in which the seer and his contemporaries lived. The Church developed a new Christian consciousness as Χριστιανοί (Du Toit 2010:588). In contrast to the intellectual and religious confusion that prevailed in the empire, the Christian community gained in its definiteness of credal confession the realisation that God is in control and that he would transform his creation (Tenney ibid:328). The Church was vigorous and active in its κηρύσσω [status confessionis]. This κηρύσσω was the reason for their victory.

The promise of Jesus' anticipated cosmic appearance suggests that some exhortation was needed by the early Christians to prevent apostasy and a return to the old way of life. The author was neither in doubt nor pessimistic. Revelation 1:7 indicates one of the ways in which 1st century Christianity expressed its identity and hope (Knight 1999:36).

Methodological approach

This article presents a discourse analysis of Revelation 1:7 based on the model of the New Testament Society of South Africa, with reference to the findings of J.P. Louw (1996:1; Du Toit 2009:217; 2004:207). According to Andrie du Toit (2009:259), this hermeneutical method is not an Aladdin's lamp that will solve all exegetical problems. It is not the exegetical method, but it has many advantages as a preparatory mechanism to open up the main contours of a given text and disclose its inner development. The caveat would be that it should be practiced in a flexible and creative manner, and with great sensitivity for the context. This method is not outdated.

The investigation is concerned with a linguistic-semantic and theological account of Revelation 1:7. Narrative, rhetorical and socio-scientific components are discernible in Revelation 1:7 (Du Rand 2007:41; Green & Pasquarello 2003:11; Neufeld & DeMaris 2010:1; Du Toit 2009:419; Robbins 1996:354).

The discussion starts with a diachronic analysis of the text. It is followed by an attempt to determine by means of a discourse analysis what the pericope concerned says, viz. the synchronic (semantic) relations. The purpose is to focus on the Lebensraum of the original readers and the meaning that the author wanted to convey (Desrosiers 2000:100; Deist 1986:129).

Revelation 1:7 within the macro context of Revelation

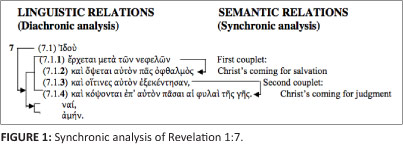

The author of Revelation uses the demonstrative particle ̉Ιδού (7.1; see Figure 1) 26 times in Revelation to highlight critical prophetic oracles (Osborne 2002:69; Aune 1997:53). It is used five times in conjunction with the verb ἔρχοµαι (7.1.1), where three occurrences give special attention to the personal appearance of Christ as in Revelation 1:7 (Rv 16:15; 22:7, 12; Aune 1997:50; Thomas 1992:76). Revelation 21:5-8 and 1:7 are oracles from Christ himself, centring around a first-person proclamation by Jesus of his appearance (Aune 1983:280). The author never uses the word παρουσία (Bauckham 1993:64).

The advent of Christ (7.1.1; ἔρχεται) is one of the primary foci of Revelation. It is also the object of praise in the doxology (Rv 1:4c). This same verb is used 11 more times in Revelation, directly or indirectly, with reference to the appearance of Christ (e.g. Rv 1:4, 8; 2:5, 16; 3:11; 4:8; 16:15; 22:7,12:20 [twice]; Thomas 1992:77). Imminence is stressed in each case.

In the development of Revelation, the personal appearance of Christ is described in chapter 19:11-16. Revelation 1:7-8 form a bridge from the doxology (Rv 1:5b-6) to John's vision on Patmos (Rv 1:9-20; Johnson 2001:49). This indicates that Revelation 1:7 is a leitmotif in the macro context of Revelation.

Significant centres in Revelation 1:1-6

The prologue of Revelation 1:1-6[7] contains the author's indicators for the correct interpretation of Revelation 1:7 as well as for the eschatology of Revelation as a whole. Revelation 1:1-6 comprises several centres (Beale 1997:45).

The author enlightens his readers right from the start about the core, focus and central motifs of his message (Coetzee 1990:253). ̉Aποκάλυψις (Rv 1:1) is an apocalyptic phrase to reveal truths that have their origins in God (Kraybill 2010:44; Rowley 1980:13; Collins 1979:61). The metaphysical world and the future of the world are revealed (Louw 1996:LN 28.38). The terms ἔδωκεν (Rv 1:1), έν τάχει, (Rv 1:1d) and καιρός έγγύς (Rv 1:3e) point to the final phase of the kingdom of God (Arndt 1996:172). It is the ultimate fulfilment - the τέλος, for his creation (Wright 2010:81; Barr 2001:101).

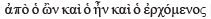

The core is the descriptive naming of God in the salutatio (Rv 1:4[8b]):  [God is the God of the future]. With this the seer motivates and establishes the future expectations of the church(es). He is because he was and he will come (Coetzee 1990:296). The last days commenced with the victory of Jesus over death, ό πρωτότοκος τῶν νεκρῶν (Rv 1:5c). The salutatio and the response of the church(es) already give voice to this.

[God is the God of the future]. With this the seer motivates and establishes the future expectations of the church(es). He is because he was and he will come (Coetzee 1990:296). The last days commenced with the victory of Jesus over death, ό πρωτότοκος τῶν νεκρῶν (Rv 1:5c). The salutatio and the response of the church(es) already give voice to this.

The eschatological preaching of the author is never mere clairvoyance - that is solely predictions about the future or one-sidedly endgeschichtlich as with pseudo-theological dispensationalism (Wright 2008:118; Coetzee 1990:253; De Smidt 1993:79). The prophet reveals the will of God and the hand of God in history. (Rv 1:1a; 1:4; 2; 3:7, 8; Wright ibid:123; Bauckham 1993:149; Coetzee ibid:295).

Revelation 1:7 is indeed one of the primary foci of Revelation (Kraybill 2010:186). God controls the history and the future of the world through the passion and second coming of Jesus.

Revelation 1:7 - A diachronic and semantic (synchronic) résumé

In Revelation 1:7 the author guides his readers to an understanding of their situation as being within the realm of God's control of the church (Rv 1:4a), history and cosmos. He owns the cosmos.

Discourse analysis of Revelation 1:7

A few critical remarks are important. According to the discourse analysis (7.1), the auto-text begins with an interjection and demonstrative particle ᾿Ιδού (7.1; Danker 2000:370). It serves to emphasise the subsequent statement (7.1.1-7.4; Louw 1996:LN 91.13), affirming the truth of the prediction of the coming of Jesus. As such it functions very much in the same way as the concluding responses ναί, ἀµήν (7:2-3). The verb ἔρχεται (7.1.1) is parallel to the verb ὄψεται (7.1.2). The subject of this verb refers back to the one in the doxology (Rv 1:5, 6), namely Jesus Christ (Thomas 1992:76). The verb ἔρχεται must then be construed as a futuristic use of the present - a usage typically found in oracles. In Revelation there are several instances of this use of ἔρχεται as futurum instans (Rv 1:4, 8; 2:5, 16; 3:11). This is not a Semitism. It means to come into a particular state or condition, implying a process - 'to become' (Louw ibid:LN 13.50).

The και (7.1.2-4) is copulative. The και that introduces three clauses (7.1.2-7.1.4) is one of the frequent ascensive uses of καὶ in Revelation (Thomas 1992:77). It indicates that the eschatological act becomes universal. The έπί plus accusative (7.1.4) after the verb (7.1.4) can indicate the object of mourning. It means to mourn for someone (Danker 2000:444; Aune 1997:51). The term αἱ φυλαì φυλή, [a clan or tribe] refers to organised human communities of varying sizes and constituencies (Aune 1997:51). The fourfold pattern (7.1.1-7.1.4) appears at the παρουσία only once in Revelation. Here, the world carries a fourfold symbolic reference. Four is the symbolic number for the world. The focus is on the world

(Coetzee 1990:257-258).

The text bears two couplets (a pair of successive sub-colas that are in accord and of the same length). The first (7.1.1) is Jesus' coming for salvation and the second (7.1.3) is the appearance for judgement.

A co-textual résumé of Revelation 1:7

The co-text refers to either the linguistic or situational environments of Revelation 1:7 (DeMoss 2001:38). Exegetes agree that the author combines two prophetic utterances from the Old Testament in his description of the appearance of Jesus (Dn 7:13; Zch 12:10; Van de Kamp 2000:63; McKnight 1989:192). This trope is inter alia called intertextuality (Moyise 2003:391). The Zechariah text was altered in two significant ways when the phrases πας ὀφθαλµός (7.1.2) and της γης (7.1.4) were added to universalise its original meaning - a narrative strategy of the author (Resseguie 2005:54; Osborne 2002:68; Beale 1999:197).

Following the salutatio and doxology (Rv 1:1-6), the writer inserts, without warning, the first prophetic oracle (Rv 1:7), introduced by the particle ʼΙδού (7.1) and then concludes with ναί, ἀµήν (7.2; 7.3) which is characteristic of early Christian prophetic speech (Aune 1997:52). The content of Revelation 1:7 confirms that Jesus Christ is the subject of ἔρχεται (7.1.1; Thomas 1992:76).

With reference to the symbolism of numbers (semiotics) in Revelation, the number seven and the threefold pattern occur (Rv 1:4b:5b; Kraybill 2010:34). On the other hand, the fourfold pattern (7.1.1-7.1.4) is used only once at the appearance of Jesus, specifically referring to the world. The number four is a symbolic reference to the world (Bauckham 1993:67; Coetzee 1990:257-258). It shows a marked distinction between God in his holiness and God and his people (Rv 1:4-6), as opposed to the world. The fourfold structural pattern strongly accentuates the fact that it is the world that is now at stake.

These end time motifs are woven throughout Revelation.1

Diachronic exegesis of Revelation 1:7

Clause 7.1: ʼIδον

Ιδού (7.1) is strategically placed as a narrative device, an attention grabber, indicating complete validation of the following statement (Louw 1996:LN 1.811, 91.13). For the hearers or readers, it articulates something new and very important, viz. the prediction of the appearance of Jesus that immediately follows (Danker 2000:370).

The phrase ʼΙδού is often used in conjunction with the verb ἔρχοµαι in Revelation (Rv 3:8; 9:20; 22:10, 22; Thomas 1992:76). It therefore gives special attention to the personal appearance of Christ.

Clause 7.1.1: ἔρχεται µετὰτῶν νεφελῶν

This verse states a theme and summarises the content of Revelation with respect to the present and future appearance of Jesus - the subject of the verb (Rv 1:5, 6). The verb ἔρχεται (7.1.1) is in the present, yet it is parallel to the verb ὄψεται (7.1.2) which is in the future. The verb ἔρχεται as a futurum instans [immanent future] is a usage typically found in oracles (Aune 1997:50; Rv 1:4, 8; 2:5, 16; 3:11). The verb means to enter into a particular state or condition which implies a process: 'to become' (Louw 1996:LN 13.50). With this futura as a guarantee of the coming appearance, the readers are called upon to anticipate the appearance of Jesus in the here and now. It could also be progressive, emphasising that the process of the appearance has been set in motion. A futuristic present stressing imminence may be the best interpretation (Osborne 2002:69).

In the New Testament various words are used for the appearance of Jesus (amongst others µαράνα θά; 1 Cor 16:22; Kraybill 2010; Scott 2008:297; Wright 2008:125).

Wright's view (ibid:125-127) is that the use of the phrase the second coming is very rare in the New Testament. The New Testament never uses the phrase second coming in reference to Jesus. It simply speaks of his imminent coming (Kraybill ibid:174). The most important Greek word παρουσία - never used in Revelation - is translated with 'coming' in the New Testament. It literally means 'royal presence' as opposed to absence (Kraybill ibid:174-175; Scott ibid:297; Wright ibid:128; Bauckham 1993:64).

The resurrection of Jesus (Jn 20:20) is a point of reference here (Kraybill 2010:175; Wright 2008:12). As he bodily appeared at his resurrection, so will he also appear bodily in the cosmic advent. His appearance on the morning of his resurrection can be a metaphor for Jesus' final appearance. Hence, the best way to interpret ἔρχεται (7.1.1) is 'to appear'. Perhaps it is for this reason that the author did not use the word παρουσία.

Christ's appearance in 7.1.1 is better understood as a process of coming throughout history, viz. eschatology in progress. Jesus is in the process of appearance (the futuristic present) and it is an anticipation of his cosmic redemption. His final appearance (Rv 22:7, 12, 20) will conclude the whole process of his appearances (Barr 2001:101; Beale 1999:199). It primarily indicates that he has been endowed with the authority to exercise end time kingship over the world (apocalyptic theology).

Here the already-not-yet view of John gains momentum. Revelation 1:7 is an anticipation of God's new creation that had already begun (Wright 2008:26). It is the Genesis 1 of the New Testament.

The term ὁ ἐρχόµενος is Christ's great name related to Old Testament prophecy (Mt 11:3; Thomas 1992:76). Jesus is the fulfilment of Old Testament, Jewish and Christian expectations (4 Ezr 13; 1 En 37-71).

Nεφελῶν (7.1.1) is a polyvalent metaphor. He appears µετά (7.1.1) and not on the clouds. It can be a spatial metaphor (Moxnes 2010:90; Resseguie 2005:81; Lakoff & Johnson 1980:14). Antiquity used 'above' as context of an alternative spatial destination or symbolic universe. It is also a sign of Godly majesty and can be described as a metaphor of triumph (Wright 2008:126; Van de Kamp 2000:62). It suggests the superhuman majesty and state of Jesus in the celestial abode of God. Clouds are also a metaphor that contrasts: the other empires are from the earth (from below), whilst Jesus comes from the clouds (from above). As the clouds come from one does not know where, so does this kingdom (Osborne 2002:70; Is 19:1). As a theophanic metaphor it escorts Christ in triumph back to earth where he was crucified and where his eternal reign will begin (Knight 1999:36). Heaven is not a future destiny, but the other hidden dimension of God (Wright ibid:115). It can also be a metaphor for spiritual and earthly conflict.

By using this idiolect, the author of Revelation altered the conscience of marginalised Christians and reinterpreted their destination (Moxnes 2010:93; De Villiers 1987:80). It is a tool for inculcating a counterculture in which there is no natural physical boundary (Green & Pasquarello 2003:151; Lakoff & Johnson 1980:27). With reference to this sacred space, the power structures are challenged and the identity formation of the Jesus movement articulated (Malina 2010:25; Berger & Luckmann 1969:120). Identity is associated with sacred space (Moxnes ibid:103). The narrative reconstructs the reader's perspective of reality by reorientating their centre of identity and power (Green & Pasquarello ibid:136).

l.For text-critical notes on Revelation 1:7, see Aune (1997:50-51).

Through this polyvalent metaphor and metaphorical dynamics, a psychological and sociocultural situation is created in which the author carries the reader into the figurative or spiritual domain, namely God's space - God's alternative for despair. It is a contextual horizon to bring meaning into the lives of the marginalised (Moxnes 2010:104). The real destination is not in the Roman imperial domain, but in God's space. The author provides his readers with a glimpse of the superior power and authority of the Messiah behind Caesar's throne (Smalley 2005:37).

The author evokes the images of his time, but gives them a new meaning. Jesus is the reality of which Caesar is a parody. With the resurrection of Jesus, the new creation of God has broken through to this old world. In the future, Jesus will appear bodily with his resurrection, and with the burst of God's creative energy, he will establish his eternal dominion - the new heaven and earth. (Wright 2008:130, 133).

This article focuses on a triumph metaphor for νεφέλη. It indicates Jesus' majestic and triumphal eschatological return to God's earth. This is the meaning of the first couplet. The metanarrative of clause 7.1.1 is that Jesus appears for the salvation of the whole cosmos and for his church (De Smidt 1994:76). He also appears for the judgment of an unfaithful world that opposed his kingdom.

Clause 7.1.2: καì ὄψεται αὐτὸν πᾶςὀφθαλµὸς

The καì; (7.1.2-4) is copulative. The καì that introduces three clauses is one of the frequent ascensive uses of και in Revelation (Thomas 1992:77; Rv 1:2). The term ὄψεται (7.1.2) with the personal accusative αὐτόν means to 'see, catch sight of, notice or sense, perception' (Danker 2000:577). The implication of this ascensive use of και is to universalise and intensify the eschatological act of judgement. Every eye in unity with the worldly mode of being against Jesus will mourn. It also gives the παρουσία universal meaning.

Cola 7.1.2 alludes to Zechariah 12:10-14 (Beale 1999:196 197; Thomas 1992:76). In altering and adapting the passage to Revelation 1:7, the writer emphasises a universality of interest in the appearance of the Lord. Such widespread attention is implied in Zechariah 12, but the words πας ὀφθαλµός (7.1.2) used in this passage make it quite explicit. It is inevitable that the whole human race will witness the return of Christ (Thomas ibid:77; Van de Kamp 2000:62). In contrast to Borg's view (Borg & Wright 2000:195) that Christ will not come again bodily, the author declares that Jesus will come again in corporeal form. He will be recognised as the very same crucified and resurrected Jesus (Smalley 2005:37). With this phrase (7.1.2) the author declares that Jesus controls space and is able to visibly present himself to all people simultaneously (Van de Kamp ibid:62).

Clarification of who is intended by πας ὀφθαλµὸς [every eye] is offered in clause 7.1.3.

Clause 7.1.3: καì οἵτινες αὐτὸνἐξεκέντησαν

There will be two groups of people that will visually register Jesus when he comes again: και οϊτινες αυτόν έξεκέντησαν (7.1.3) and πασαι αί φυλαι της γης (7.1.4). The second group is discussed in clause 7.1.4. Two hermeneuces are implied here (Jordaan, Van Rensburg & Breed 2011:244; Smalley 2005:37).

The first group (7.1.3) is a reference to the soldiers who crucified Jesus and is representative of the Jews and Romans who orchestrated the crucifixion. The inclusion of the Romans is likely in the present clause, because anti-Romanism is apparent in Revelation (Thomas 1992:78).

Another view is that οϊτινες is generic, pointing to the second group who, in every age, shares the indifference of hostility that lies behind their acts (Groenewald 1986:37; Swete 1911:10). Those referred to in this clause are a class within the human race indicated by 'every eye' of the previous clause.

Clause 7.1.4: και κόψονται έπ' αυτόν πασαι αί φυλαι

Akin to 7.1.3 is colon 7.1.4, although the reference in 7.1.4 is much more inclusive. All the families of the earth will lament on his account (Smalley 2005:38).

The term κόψονται means to beat one's breast as an act of mourning. The έπί and accusative αυτόν (7.1.4) after the verb κόπτω (7.1.4) can indicate the object of mourning. It means to mourn for someone (Danker 2000:444; Aune 1997:51). The adjectives πας (7.1.2) and πασαι (7.1.4) are parallels.

The final clause lends itself to two possible interpretations (Thomas 1992:78).

Firstly, Πασαι αί φυλαι (7.1.4) can refer to the literal tribes of Israel who will be judged (Beale 1999:26). Της γης (7.1.4) refers to the land promised to Abraham, the land of Israel, as in Zechariah 12:12. When the leading role played by the Jews in the crucifixion of Christ is noted (Jn 19:37; Acts 2:22, 23; 3:14, 15), it strengthens the case for the explanation of these words as alluding to the tribes of Israel (Thomas 1992:78). Another supporting consideration is the consistent use of αί φυλαι; in the LXX and New Testament referring to the tribes of Israel (Thomas ibid:78).

A second way of explaining the last clause (7.1.4b) is as follows:

1. πασαι αί φυλαι (plural of φυλή) refers to all the families of the earth - not only the Jewish tribes.

2. της γης refers to the earth in the sense of the whole world. Γη cannot be a limited reference to the country of Israel, but has a universal denotation. Revelation 1:7 implies an extension of the Old Testament concept of Israel. The nation in Zechariah 12 is transferred to all the peoples of the earth (Beale 1999:197).

3. κόψονται refers to the mourning of despair by a sinful world over the judgement of Christ at his return. Jesus' use of the same passage to denote a mourning of despair in Matthew 24:30 strongly favours this approach (Thomas 1992:78; Beale 1999:197).

The strongest evidence favouring this second view is the later context of Revelation where mourning is generally the remorse that accompanies the disclosure of the coming divine judgement (Rv 16:9, 11, 21). Revelation uses universalistic language (Bauckham 2005:239). However, each of the two explanations has respectable support.

In Revelation there are difficulties with the first perspective. Zechariah 12:10 combined with Daniel 7:13 does not prophesise Israel's judgement, but Israel's redemption. There is a difference between Zechariah's and Revelation's view with respect to Israel (Zch 12:10-14; Rv 14:16; Du Rand 2007:129; Beale 1997:26; Bauckham 1993:319-322). Thomas' critique (1992:79) is inter alia that not too much can be made of the limited Jewish scope of αί φυλαι in the LXX and the rest of the New Testament, because Revelation uses the word more broadly to refer to the peoples of all nations (Rv 5:9; 7:9; 11:9; 13:7; 14:6). The πασαι αί φυλαι της γης (7.1.4) never refers to Israelite tribes. By using all the tribes of της γης (7.1.4), Revelation transfers what is said of Israel in Zechariah 12 to all the peoples of the earth. Along with this change το πασαι αί φυλαι της γης, Revelation 1:7 universalises πας οφθαλµός (7.1.2; Beale ibid:26). The author adheres to and consistently develops the contextual ideas of his Old Testament references.

According to Aune (1997:51), φυλαι (φυλή [clan or tribe] is a term for various forms of social organisation, usually a constituent element of πόλις [city, state], or έθνος [nation]. The term can also be used in the broader sense of 'people' (Aune ibid:51). He has chosen 'society' because it is elastic -referring to organised human communities of varying sizes and constituencies (Aune ibid:51).

When weighing all the considerations in Revelation 1:7, it points to the second option as the correct meaning of this clause. Clause 7.1.4 is the human race in totality - fallen humanity, inclusive of all those who rejected his power (Osborne 2002:70). It may include the whole course of the church age during which Christ guides the events of history in judgement and blessing (Beale 1999:197).

This is probably not a reference to every person without exception, but to all amongst the nations who do not believe as clearly indicated by the universal scope of 'tribe' in Revelation 5:9 and 7:9. The plural of φυλή is a universal reference to unbelievers in Revelation 11:9, 13:7 and 14:6 (Beale 1999:26).

The nations do not mourn over themselves, but over Jesus (Beale 1999:197; 7.1.3), the subject of the verb έρχεται (7.1.1) which is a more suitable understanding of shame (Rohrbaugh 2010:109). They will lament in shame, not in godly repentance, but in fear and guilt, because they will be obliged to face their judge (Koester 2001:51; Krodel 1989:87; Rv 6:16-17; 14:9-11; 19:11-16).

Taken in this sense, Revelation 1:7 provides a grim preview of what lies ahead for the world. The return of Christ is anything but a comfort to those who persist in their rebellion against him (Borg & Wright 2000:198; Thomas 1992:79). The verb κόψονται (7.1.4) pictures the hopeless bitterness of this grief. This is a worldwide recognition (Giblin 1991:42). It proves the opposite of the viewpoint of the chiliastic and preterist eisegesis (De Smidt 1993:79). The unbelieving world will see him and lament (Osborne 2002:70; Van de Kamp 2000:61). In this context, the country and people of Israel have no function.

The judgement of Jesus on the cross now becomes the judgement of the unbelievers. In addition the cosmic victory of Christ on the cross now reverberates in the victory of the faithful. The prominent prayer of the believers is answered. The kingdom of Christ has come - his will is done on earth as it is in heaven (Mt 6:10). This is the ultimate purpose of God with his creation (Wright 2008:16). This is the meta-language of Revelation 1:7.

Clauses 7.2-7.3: ναί, αµήν

Ναί, αµήν (7.2; 7.3) is a double affirmation to the certainty of fulfilment of the prophetic oracle (7.1-7.1.4) or the two couplets. It strengthens the certainty of what has just been prophesied (Thomas 1992:79). It means that it is absolutely fixed that the coming of Christ will happen as prophesised and will bring with it the resultant effects described in Revelation 1:7.

The community responds to this with an 'amen', both in Greek and in Hebrew, attesting God's promissory word and their trust in it (Du Rand 2007:129; Giblin 1991:42). Ναί [Greek] is the usual word of affirmation followed by the Hebrew word of affirmation, αµήν. In combination, they strengthen the certainty of what has just been prophesied (Thomas 1992:79). Ναί (7.2) is an emphatic particle. It is used in this way three times in Revelation (Rv 1:7; 16:7; 22:20; Du Rand ibid:129). Christ himself is ό αµήν (Rv 3:14).

Ναί is the divine promise, and αµήν the human acceptance that Jesus will appear again.

Conclusion

Revelation 1:7 is an anticipation of the final appearance of Jesus as Christ Victor at the consummation of the old worldly order. This is the climax of the transition of the historical to the supra-historical, the final phase of the kingdom of God. The first couplet is an indication that Jesus will appear on the clouds, a metaphor for his majestic and triumphal eschatological return to God's earth.

Christ's appearance is understood as a process occurring throughout history - eschatology in progress. The process of his appearance has been set in motion by his resurrection. His final appearance from God's space will conclude the whole process of his appearances in history.

A metanarrative is that Jesus appears for the salvation of the whole cosmos as well as for his church. However, he also appears for the judgement of an unfaithful world that opposed his kingdom. The author of Revelation declares that Jesus controls the space and is able to visibly present himself simultaneously to all people.

It is inevitable that the totality of the human race will witness the return of Christ. The unfaithful are a class within the human race. It is not a reference to every person without exception, but to all those amongst the nations who do not believe.

The resurrection of Jesus and his appearance from God's space can be a simile for his final appearance. With Jesus' resurrection, God's new world became a reality. It is the Genesis 1 of the New Testament. As he bodily appeared at his resurrection, so will he also appear bodily in the cosmic advent. With the burst of God's creative energy, he will establish his eternal dominion - the new heaven and earth.

The eschatological preaching of the author is never one-sidedly endgeschichtlich as with the pseudo-theological dispensationalism and its focus on the land or people of Israel. The context of Revelation 1:7 does not indicate the repentance of the people of Israel as the chiliasts see it.

Concerning the final end time, Revelation 1:7 is particularly reserved. Whilst some (e.g. chiliasm) are inclined to an adjunct to time, Revelation 1:7 is sparing in its phrasing of the final circumstances. From the human viewpoint it may be imminent, but from the perspective of God it may be some time yet.

Revelation 1:7 is indeed one of the primary foci of Revelation (Kraybill 2010:186). Revelation 1:7 is our lively hope - the grand finale - and the metanarrative of God's τέλος for his church and his creation.

Acknowledgements

Competing Interest

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article.

References

Arndt, W., 1996, A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature, University of Chicago Press, Chicago. [ Links ]

Aune, D.E., 1983, Prophecy in early Christianity and the ancient Mediterranean world, William B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Aune, D.E., 1992, 'Early Christian eschatology', in D.N. Freedman (ed.), The Anchor Bible Dictionary, Doubleday, New York, pp. 594-605. [ Links ]

Aune, D.E., 1997, Revelation 1-5, Word Books, Dallas. [ Links ]

Balz, H. & Schneider, G. (eds.), 1991, Exegetical dictionary of the New Testament, vol. 2, William B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Barr, D.L., 2001, 'Waiting for the end that never comes: The narrative logic of John's Story', in S. Moyise (ed.), Studies in the Book of Revelation, pp. 101-112, T&T Clark, Edinburgh. [ Links ]

Bauckham, R.J., 1993, The theology of the Book of Revelation, University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Bauckham, R.J., 1996, 'Eschatology', in J.D. Douglas (ed.), New Bible Dictionary, pp. 330-345, InterVarsity Press, Leicester. [ Links ]

Bauckham, R.J., 2005, The climax of prophecy, T&T Clark, London. [ Links ]

Beale, G.K., 1997, 'The conception of New Testament theology', in K.E. Brower & M.W. Elliott (eds.), The reader must understand, pp. 11-52, Apollos, England. [ Links ]

Beale, G.K., 1999, The Book of Revelation, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Berger, P. & Luckmann, T., 1969, The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge, The Penguin Press, London. [ Links ]

Borg, M.J. & Wright, N.T., 2000, The meaning of Jesus: Two visions, HarperCollins Publishers, San Francisco. [ Links ]

Boshoff, P., 2001, 'Apokaliptiek en eskatologie: Die verband en onderskeid volgens Schmittals', Hervormde Teologiese Studies 57(1&2), 563-575. [ Links ]

Bruce, G.A., 1986, 'Apocalyptic eschatology and reality - An investigation of cosmic transformation', DTh thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Coetzee, J.C., 1990, 'Die prediking (teologie) van die Openbaring aan Johannes', in A.B. du Toit (ed.), Handleiding by die Nuwe Testament, vol. 5, pp. 253-314, NG Kerkboekhandel, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Collins, A.Y., 1979, 'The early Christian apocalypses', Semeia 14, 61-69. [ Links ]

Danker, F.W. (ed.), 2000, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian Literature, University of Chicago Press, Chicago. [ Links ]

Deist, F. (ed.), 1986, A concise dictionary of theological terms, J.L. van Schaik, Pretoria. [ Links ]

DeMoss, M.S., 2001, Pocket dictionary for the study of New Testament Greek, InterVarsity Press, Illinois. [ Links ]

DeSilva, D.A., 1992, 'The Revelation of John: A case study in apocalyptic propaganda and the maintenance of sectarian identity', Sociological Analysis 53(4), 375-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3711434 [ Links ]

De Smidt, J.C., 1993, 'Chiliasm: An escape from the present into an extra-biblical apocalyptic imagination', Scriptura 45, 79-95. [ Links ]

De Smidt, J.C., 1994, 'Revelation 20. Prelude to the omega point: New heaven and earth', Scriptura 49, 75-87. [ Links ]

Desrosiers, G., 2000, An introduction to Revelation, Continuum, London. [ Links ]

De Villiers, P.G.R., 1987, Leviatan aan 'n lintjie. Woord en wêreld van die sieners, Serva-Uitgewers, Pretoria. PMCid:PMC1778439 [ Links ]

Duling, D.C., 2003, The New Testament. History, literature, and social content, Wadsworth/Thompson, Belmont. [ Links ]

Du Rand, J.A., 1991, 'God beheer die geskiedenis: 'n Teologies-historiese gesigspunt volgens die Openbaring van Johannes', in J.H. Roberts (ed.), Teologie in konteks, pp. 583-596, Orion, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Du Rand, J., 2007, Die A-Z van Openbaring. 'n Allesomvattende perspektief, CUM, Vereeniging. [ Links ]

Du Toit, A.B., 2004, 'Het diskoersanalise 'n toekoms?', Hervormde Teologiese Studies 60(1&2), 207-220. [ Links ]

Du Toit, A.B. (ed.), 2009, Focusing on the message. New Testament hermeneutics, exegesis and methods, Protea, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Du Toit, A.B., 2010, 'Translating Romans: Some persistent headaches', In die Skriflig 44(3&4), 581-602. [ Links ]

Giblin, C.H., 1991, The Book of Revelation: The open book of prophecy, A Michael Glaziel, Liturgical Press, Collegeville. [ Links ]

Greshake, G., 2005, 'Eschatology', in J.Y. Lacoste (ed.), Encyclopedia of Christian Theology, vol. 1, pp. 489-491,Routledge, New York, [ Links ]

Green, J.B. & Pasquarello III, M. (eds.), 2003, Narrative reading, narrative preaching. Reuniting New Testament interpretation and proclamation, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Groenewald, E.P., 1986, Die Openbaring van Johannes, NG Kerk-Uitgewers, Kaapstad. [ Links ]

Johnson, D.E., 2001, Triumph of the Lamb: A commentary on Revelation, P&R Publishing, Phillipsburg. [ Links ]

Jordaan, G.J.C., Van Rensburg, F.J. & Breed, D.G., 2011, 'Hermeneutiese vertrekpunt vir Gerefomeerde eksegese', In die Skriflig 45(2, 3), 225-258. [ Links ]

Knight, J., 1999, Revelation, Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. [ Links ]

Koester, C.R., 2001, Revelation and the end of all things, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Kraybill, J.N., 2010, Apocalypse and allegiance. Worship, politics, and devotion in the Book of Revelation, Brazos Press, Grand Rapids. PMCid:PMC3780573 [ Links ]

Krodel, G., 1989, Revelation, Augsburg, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M., 1980, Metaphors we live by, University of Chicago Press, Chicago. PMid:11661871 [ Links ]

Louw, J.P., 1996, Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament: Based on semantic domains, United Bible Societies, New York. [ Links ]

Malina, B.J., 2010, 'Collectivism in Mediterranean culture', in D. Neufeld & R.E. DeMaris (eds.), Understanding the social world of the New Testament, pp. 17-27, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

McKnight, S. (ed.), 1989, Introducing New Testament Interpretation, Baker Books, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Moxnes, H., 2010, 'Landscape and spatiality: Placing Jesus', in D. Neufeld & E. DeMaris (eds.), Understanding the social world of the New Testament, pp. 90-106, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Moyise, S., 2003, 'Intertextuality and the use of scripture in the Book of Revelation', Scriptura 84, 391-401. [ Links ]

Neufeld, D. & DeMaris, E. (eds), 2010, Understanding the social world of the New Testament, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Osborne, G.R., 2002, Revelation, Baker, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Petersen, D.L., 1992, 'Eschatology', in D.N. Freedman (ed.), The Anchor Bible Dictionary, Doubleday, New York, vol. 2, pp. 575-579. [ Links ]

Resseguie, J.L., 2005, Narrative criticism of the New Testament. An introduction, Baker Academic, Grand Rapids. PMid:16192377 [ Links ]

Robbins, V.K., 1996, 'The dialectical nature of early Christian discourse', Scriptura 59, 353-362. [ Links ]

Rohrbaugh, R.L., 2010, 'Honor. Core value in the Biblical world', in D. Neufeld & E. DeMaris (eds.), Understanding the social world of the New Testament, pp. 109-1124, Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Rowley, H.H., 1980, The relevance of Apocalyptic, Attic Press, Greenwood. [ Links ]

Schrage, W., 1988, The ethics of the New Testament, Fortress, Philadelphia. PMid:3198499 [ Links ]

Scott, J.J., 2008, New Testament Theology, WS Bookwell, Finland. [ Links ]

Slater, T.B., 1998, 'On the social setting of the Revelation to John', New Testament Studies 44(2), 232-256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0028688500016490 [ Links ]

Smalley, S.S., 2005, The Revelation to John. A commentary on the Greek Text of the Apocalypse, InterVarsity Press, Illinois. [ Links ]

Swete, H.B., 1911, The Apocalypse of St John, Macmillan & Co. Ltd., London. [ Links ]

Tenney, M.C., 2004, New Testament Times, Baker Book House Company, Grand Rapids. [ Links ]

Thomas, R.L., 1992, Revelation 1-7: An exegetical commentary, Moody, Chicago. [ Links ]

Van de Kamp, H.R., 2000, Openbaring, Kok, Kampen. PMid:11010912 PMCid:PMC92338 [ Links ]

Wright, N.T., 2008, Surprised by hope: Rethinking heaven, the resurrection, and the mission of the church, HarperOne, New York. [ Links ]

Wright, N.T., 2010, After you believe. Why Christian character matters, HarperCollins Publishers, New York. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Kobus de Smidt

PO Box 39543, Moreleta Park 0044, South Africa

kobusjc@vodamail.co.za

Received: 24 July 2012

Accepted: 27 Aug. 2013

Published: 29 Nov. 2013

1- For text-critical notes on Revelation 1:7, see Aune (1997:50–51).