Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Koers

versão On-line ISSN 2304-8557

versão impressa ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.87 no.1 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.87.1.2535

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Workplace spirituality: The fifth gospel for the modern workplace?

Werkplekspiritualiteit: Die vyfde evangelie vir die moderne werkplek?

Laetus OK LateganI; Deseré KoktII

IResearch, Innovation and Engagement Division Central University of Technology, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6494-3882

IIFaculty of Management Sciences, Central University of Technology, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6460-8547

ABSTRACT

n this article, the argument Is developed that workplace spirituality can be used within practica theology to understand developments within the workplace. This can enable the church to give effective guidance to the congregation on finding meaning and purpose within the workplace. The value of workplace spirituality for both practical theology (as science) and the church (as organisation) will be debated in this article. In this article, it is accepted that workplace spirituality is not the same as religion even though the two concepts are not disjoint. This article first attends to workplace spirituality and then to the role of practical theology in workplace spirituality.

Based on the discussion of the difference between religion and spirituality, and what spirituality is, including the dimensions of spirituality, the working definition used in this article is that workplace spirituality engenders spiritual growth and development of employees which creates purpose, meaning, and community within the organisational context.

In the part on practical theology, it is argued that practical theology has three domains, namely the church, society, and academia (or science). The study presents the perspective that the workplace is a study focus for practical theology. The practice of workplace spirituality should be studied in practical theology thereafter practical theology can develop a faith-based approach to spirituality. This can be useful to understand the construct and practice of faith-based workplace spirituality without the one faith tradition dominating over the other.

Keywords: workplace spirituality, practical theology, religion, responsibility.

ABSTRAK

In hierdie artikel word die argument ontwikkel dat werkplekspiritualiteit deur die praktiese teologie gebruik kan word om ontwikkelings binne die werkplek te verstaan. Dit kan die kerk help om effektiewe leiding aan die kerkgemeenskap te gee om sin en betekenis binne die werkplek te vind. Die waarde van werkplekspiritualiteit vir die praktiese teologie (as wetenskap) en die kerk (as organisasie) word in die artikel gedebateer. Die artikel vertrek vanuit die standpunt dat hoewel werkplekspiritualiteit en godsdiens nie dieselfde is nie, dit ook nie geskei behoort te word nie. Die artikel gee eers aandag aan werkplekspiritualiteit en dan aan die ro van die praktiese teologie in werkplekspiritualiteit.

Die besprekings oor die verskil tussen werkplekspiritualiteit en godsdiens, wat werkplekspiritualiteit is asook die onderskeie dimensies daarvan word gebruik vir 'n werkdefinisie van werkplekspiritualiteit. In hierdie artikel word werkplekspiritualiteit gedefineer as die ontwikkeling van die spirituele groei van werknemers wat doel, betekenis en gemeenskap binne organisatroriese verband skep en bevorder.

Die arikel wys op drie domeine van praktiese teologie, naamlik kerk, gemeenskap en wetenskap. Die werkplek is 'n studiefokus vir die praktiese teologie. Die beoefening van werkplekspiritualiteit moet deur die praktiese teologie bestudeer word waarna 'n geloofsgebaseerde benadering tot werkplekspiritualiteit ontwikkel kan word. Dit kan betekenisvo wees om die inhoud en beoefening van geloofsgebaseerde werkplekspiritualiteit te verstaan sonder dat een geloofstradisie 'n ander oorheers.

Sleutelwoorde: werkplekspirituaiteit, praktiese teologie, godsdiens, verantwoordelikheid.

1. Introduction

In the midst of dynamic economic forces and technological breakthroughs, organisations are set to play the leading role in shaping and creating modern society (Arkenberg, Lee, Evans, & Westcott, 2022). One way of doing this is to create an organisation that is attuned to the needs of its employees - since employees are the ones responsible for driving the organisation forward and creating the much-needed competitive advantage. As employees seek greater engagement and a sense of fulfilment in their jobs, the notion of workplace spirituality has become increasingly prominent (Chawla & Guda, 2013; Van Tonder & Ramdass, 2009). Employees are progressively re-examining the meaning and purpose of their work and private lives (Mohan & Uys, 2006).

There are several contributing factors informing the growth in workplace spirituality. Naidoo (2014) identifies the transition from work as survival to work as livelihood. This transition corresponds with Steenkamp and Basson's (2013) emphasis on what constitutes a meaningful workplace and how the basis of a Protestant work ethics can be promoted within the modern workplace. Both Fourie (2014) and Schutte (2016), amongst many other authors, confirm the value of workplace spirituality. One such example is confirmed by Van der Walt and Steyn (2019) and McGhee and Grant (2008) who comment on the positive effect workplace spirituality has on ethical behaviour. Schutte (2016) remarks that workplace spirituality is much more than a developmental tool, a temporary response to post-modern decline of religion or to accommodate diversity in the workplace. According to Chawla and Guda (2013), there is also a growing tendency among organisational researchers to have a greater focus on spirituality as a means of fostering individual well-being and organisational stability.

There is mounting evidence that a more spiritual workplace is not only more productive and committed, but also more flexible and creative and a source of sustainable competitive advantage (Fry & Slocum 2008; Rathee & Rajain, 2020; Van Tonder & Ramdass, 2009).

In essence this confirms the value of workplace spirituality. This value is not limited to management or social sciences only but has a wider reach such as practical theology dealing with a theologia habitus informing the praxis of the church as a faith-based organisation. The value of workplace spirituality for both practical theology (as science) and the church (as organisation) will be argued in this article.

The position taken in this article is not that workplace spirituality is replacing religion but rather that it has a complementary value for educating future pastors to guide their congregation in finding meaning in the workplace, lived by their faith-based conviction regardless religious neutral workplaces, diversity of workers' own religious orientations and contribute towards upholding integrity in the workplace regardless the challenges of a corrupt society and the need to enhance responsible citizenship behaviour.

The above position is grounded in McGhee and Grant's comment (2008) that the link between religion and work is not new. Through-out the ages people have been interpreting their work based on religious values. However, there is an observable paradigm shift on how work is perceived. When considering the modern workplace spirituality rather than religion is the better construct to emphasise the understanding of the relationship between the individual and modern pluralistic workplaces.

This positive value of workplace spirituality is often overshadowed by the decline in public religion and the practice thereof. The neo-Calvinistic idea of practicing religion and faith in all spheres of live is fading away and is evident in public life such as the workplace, education institutions and organisations. A contributing factor is the decline of religiousness and religious individualism in the post-modern society. It appears that religion has become uncoupled from spirituality since the 1960s (Liu & Robertson, 2011). A possible reason for this is the social change that characterise the fibre of societies as they evolve and adapt to new developments and changing values.

Consequently, employees are searching for increased meaning and purpose in the workplace resulting in an intensified focus on spirituality. Whereas religion refers to formalised beliefs and social structure, spirituality is regarded as private and personal in nature. This view of spirituality implies an inner search for meaning or fulfilment that may be undertaken by anyone regardless their religion (Wainaina, Iravo, & Waititu, 2014). Wainaina et al. (2014) labels this view as intrinsic, which renders spirituality a highly individual quality which does not necessarily entail any connection to a specific religion. Instead, it is based on personal values and philosophy, originating from the individual. Again, this does not mean that there can be no link between spirituality and religion.

As already mentioned, workplace spirituality has become an increasingly important concept for organisational leaders and managers during the past two decades (Rathee & Rajain, 2020). Workplace spirituality supports people's desire to live integrated, holistic lives, including recognition and acceptance of their spirituality in the work context. Aravamudhan and Khrishmaveni (2014) note that the proliferation of the concept is noticeable in many books and academic articles that debate the term. According to Karakas (2010) there are three interconnected perspectives of workplace spirituality, namely a human resource perspective (which enhance employee well-being and quality of life), a philosophical perspective (which maintains that spirituality provides employees with a sense of meaning and purpose in the workplace), and an interpersonal perspective (which offers employees a sense of interconnectedness and community).

In this article the argument is developed that workplace spirituality is a meaningful development that can be used within practical theology as scientific discipline to understand developments within the workplace. This can enable the church to give effective guidance to members of the congregation on finding meaning and purpose within the workplace. This focus is necessitated by the reduction of human beings as homo economicus (Geybels & Van Stichel, 2018). This implies that a person is reduced to an economic object only and the focus is now on the individual and not the fellow person. The argument that will be developed is based on a conceptual discussion of workplace spirituality and what should be considered as useful for practical theology when this concept is further unpacked as part of discipline discourse (practical theology) and praxis (church life).

Schutte (2016:5) foresees a positive role for practical theology alongside management science on the role of spirituality in the workplace of the future through developing an industry-specific body of knowledge on workplace spirituality. His view is based on that strategic leaders and employees already have spiritual beliefs. These beliefs influence their leadership styles and their day-to-day operations in the workplace.

A first starting point is the delineation of the concept "religion" and "spirituality".

2. Delineating the concept 'religion' and 'workplace spirituality'

The concepts 'religion' and 'spirituality' are associated with faith and personal orientation. Helminiak (2006) notes that spirituality is a topic within the psychology of religion. Differentiation between spirituality and religion, however, is not easy and there seems to be ongoing debate in the literature whether spirituality is a separate construct from religion (Bell, 2012; Fry, 2003). Marques (2006) indicates that in essence religion is concerned with faith, while spirituality is regarded as broader than any single formal or organised religion with its prescribed tenets, dogma, and doctrines.

Liu and Robertson (2011) provide a valuable distinction between spirituality and religion. Spirituality is the privatisation of religion, which is informal, personal, universal, nondenominational, inclusive, tolerant, positive, individualistic, less visible, quantifiable, subjective, emotionally oriented, and inwardly directed. It is also less authoritarian. It further involves little external accountability and is appropriate to express in the workplace. Religion on the other hand is formal, organised, dogmatic, institutional, community focused, more observable, measurable, objective, and behaviour oriented. It also leans more toward doctrine and is often inappropriate to express in the workplace. Long and Mills (2011) note that within the business literature there is agreement that spirituality and religion represent the employee's search for increased connectedness and meaning in life.

Spirituality and religion should not be seen as mutually exclusive. These concepts are not the same although interrelated. Each one has a role to play in a person's life. To ground this observation, the following:

Liu and Robertson (2011) support the interrelatedness of religion and spirituality by postulating that spirituality is a broader construct that incorporates and transcends religiosity. Izak (2012) supports the distinction between spirituality and religion after analysing a representative sample of different definitions of spirituality derived from academic literature and empirical research. He found that spirituality in an organisational context is not interpreted as being the same as religion, nor closely connected with any religious tradition (such as Christian, Judaism, Muslim, etc.). Sorakraikitikul and Siengthai (2014) note that within the modern work context policies related to non-discrimination based on religion is prolific and enforced by organisations. This notion supports the assertion of Liu and Robertson (2011) that due to the dogmatic nature of religion it is not appropriate to express it in the workplace. This again attests to changing societal values as this was not necessarily the case in previous generations.

Authors like Mitroff and Denton (1999) and Fry (2003) agree that spirituality is related to personal growth whereas religion relates to the regulation of human behaviour. Religion per se is also regarded as more fixed than spirituality and faith forms the bases of religion. According to Bergunder (2014) religion encapsulates organised practices that define religious denominations including traditions and rituals on a personal or institutional level in celebrating a divine being or higher power. Religion can therefore be described as institutionalised beliefs that find visibility in public rituals and organised doctrines.

Examining the relationships between work, religion and spiritual life is not new as it can be traced to the social theorising of Weber, Durkheim and Freud (Case & Gosling, 2010). The proliferation of research on the topic is evident in the launch of The Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion in 2004 and coincides with the work of James, Miles and Mullins (2011) which found that spirituality and management have become linked through the increased realisation that promoting workplace spirituality can help improve job and organisational performance. In this study it is accepted that workplace spirituality is not the same as religion even though the two concepts are not disjoint.

In meeting the stated aim of the article (see paragraph 1), it is also important to have a broader view of workplace spirituality.

3. Workplace spirituality in context

There are various nuances in describing workplace spirituality mainly due to the proliferation of published research during the 1990s and early 2000s (see Benefiel, 2003; Brown, 2003; Delbecq, 1999; Eisler & Montouori, 2003; Fry, 2003; Kinjerski & Skrypnek, 2004; Leigh, 1997; Sass, 2000; Wagner-Marsh & Conely, 1999). Form their research a link is postulated between workplace spirituality and increased commitment to organisational goals. It furthermore accentuates that workplace spirituality garners increased honesty and trust within the organisation, greater kindness and fairness, increased creativity, increased profits, improved morale, enhanced organisational performance and productivity, organisational development, as well as reduced absenteeism and turnover.

Benefiel, Fry, and Geigle (2014) track the origin of the notion of workplace spirituality back to the 6th century, where St Benedict (c. 480-543) provided rules for monastic life, integrating work and prayer. During the First Industrial Revolution, Protestants developed a work ethic called 'Protestant Work Ethic' with the aim to spiritualise the workplace. The post-industrial period saw the emergence of economic wealth as an end, devoid of the principles that could enrich the employee's life. Initial research on spirituality was mainly conducted in the fields of psychology and psychiatry, with a focus on individual spirituality. Van der Walt and De Klerk (2014) state that it is only from 2000 onward that the focus shifted to include workplace spirituality within the field of organisational behaviour.

Though workplace spirituality appears to be a relatively novel field of study, the emergence of the concept can be traced back to the late 19th century in Europe and the United States, and the 'Faith at Work' movement (Benefiel et al., 2014). This movement emerged in response to the lack of interest that the church displayed toward people's experiences in the workplace. The main impetus of this movement was the acknowledgement of the depth and breadth of workplace spirituality and its influence on the success of an organisation.

Mohan and Uys (2006) reiterate that the search for spirituality and its integration with everyday work life has gained momentum during the 1990s as many individuals started re-examining the meaning of work and question the meaning and purpose of their lives. Garcia-Zamor (2003) maintains that this happened in reaction to the corporate greed of the 1980s. More specifically, Neal and Biberman (2003) note that the sudden increase in conferences, books and workshops on spirituality in the workplace started around 1992. This has contributed to a re-examination of the nature and meaning of work by especially Americans escalated by the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 (Neal & Biberman, 2003). Fry and Slocum (2008) even go so far as to regard workplace spirituality as the missing attribute informing both organisational performance and individual well-being, where work and spirituality are integrated and where employees are assisted to lead more holistic lives. Workplaces that are more spirituality enhance individual creativity, promote a sense of personal fulfilment, increase individual job performance, joy, peace, serenity, and job satisfaction. The spiritual worker is thus likely to experience feelings of connectedness with colleagues and the larger organisation (Marques, 2006).

Several studies on workplace spirituality correlate positively with the following variables: organisational commitment (Geigle, 2012), organisational effectiveness (Karakas, 2010), positive leadership (Phipps, 2012), job satisfaction and well-being (Pashak & Laughter, 2012), work ethics (Issa & Pick, 2011), and social justice (Prior & Quinn, 2012).

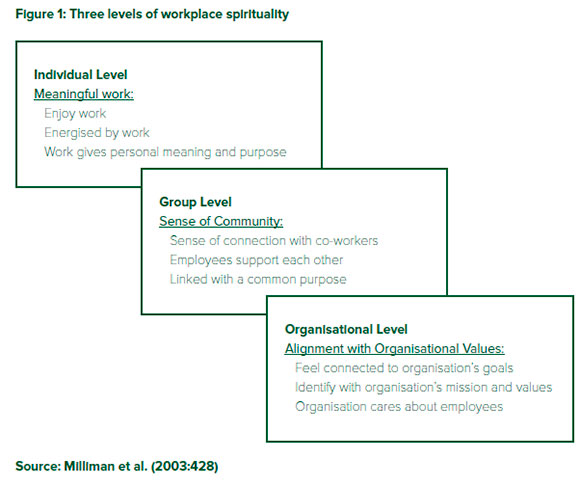

Kolodinsky, Giacalone and Jurkiewicz (2008) identified three levels of spirituality at work, namely the individual level (a reflection of one's personal spiritual orientation), the organisational level (the organisation's spiritual climate and culture); and the level where the two interact. Houghton, Neck and Krishnakumar (2016) note that at the individual level, workplace spirituality is measured in terms of individual perceptions of inner life, meaningful and purposeful work, and a sense of community and connectedness. Organisation-level workplace spirituality describes the spirituality of the organisation itself and relates to the spiritual climate or culture of the organisation as depicted in its values, vision, and purpose (Benefiel et al., 2014).

According to Bell (2012) the individual level entails the extent to which employees can obtain internal and external job satisfaction through meaning and purpose in their work. The work-unit (job) level refers to the sense of community with other employees, while the organisation-wide level refers to the perception of the relationship between the individual and the organisation (Mohamed & Ruth, 2016; Nooralizad, Ghorchian, & Jaafari, 2011; Tagavi & Janani, 2014). This implies that the individual employee is likely to experience workplace spirituality in as far as there is alignment between his/her values and goals and that of the organisation. The figure below depicts the three levels at which workplace spirituality is evident, as conceptualised by Milliman, Czaplewski, and Ferguson (2003).

The next focus is to look closer to dimensions of workplace spirituality.

4. Dimensions of workplace spirituality

Based on the literature of workplace spirituality that was reviewed for this study, it is apparent that conceptual convergence has emerged (BinBakr & Ahmed, 2015; Mohamed & Ruth, 2016; Tolentino, 2013; Wainaina, et al., 2014). The convergence occurs in three recurring themes that can be regarded as the dimensions of workplace spirituality that will be embraced for purposes of this study. These dimensions are sense of meaning, sense of purpose and sense of community.

Wilson (2013) notes that without a sense of purpose employees can become alienated from their work and find it harder to motivate themselves. Jobs exist for a reason and when employees fully understand their contribution to the organisation it enhances their sense of purpose. Dave and Wendy Ulrich explained in their 2010 book 'The Why of Work' that there are many advantages to helping people find purpose in their jobs (Ulrich & Ulrich, 2010). They indicate that people who understand their job's wider purpose are happier, more engaged, and more creative. When individuals understand how their jobs align with the company's goals, it reduces staff turnover and increases productivity. It appears that people with a sense of purpose tend to work harder, use initiative, and make sensible decisions. A sense of purpose therefore contributes to the organisation operating more efficiently. Based on the above discussion, it is fair to accept that if employees experience a greater sense of meaning and purpose in the workplace, this makes them feel valued.

Employees spend a large amount of time performing their jobs and this can often lead to detachment from family and friends. Sense of community can assist employees to feel connected and thus experience spiritual fulfilment. The experience of sense of community can lead to the awakening of an inner sense (spirituality) in employees to find the meaning and purpose of their work (Wahid & Mustamil, 2014). Thus, a sense of community can be regarded as the metaphysical part of ourselves and our work, an awareness of something beyond the world as we know it. This 'something' can be other people, a cause, nature, or a belief in a higher power (Ashforth & Pratt, 2003). Thus, the social connection between employees enhances self-esteem and sense of community and inadvertently the sense of meaning and purpose. It will suffice to say that community with others in the workplace has become the substitute for the traditional family and community structures that the modern employee has become alienated from. When employees experience fulfilment and meaning in the workplace it enhances their self-esteem. This in turn makes it easier to experience an enhanced sense of community without losing one's sense of personal identity.

The dimensions of workplace spirituality (sense of meaning, sense of purpose and sense of community) as set out above provide direction and cohesiveness to an organisation and its employees. Within the modern organisation there is evidence of an increased integration of workplace spirituality through activities like Employee Assistance Programmes (EAPs), wellness programmes and diversity programmes among others.

Based on the discussion of the difference between religion and spirituality, what spirituality is, including the dimensions of spirituality, the working definition used in this study is that workplace spirituality engenders spiritual growth and development of employees which creates purpose, meaning and community.

5. Connecting practical theology to workplace spirituality

Individualism is a leading trend of late modern societies. It can therefore be expected that in church life this approach should be found back in pastoral care and preaching. Gartner (2015: 32-42) lists some characteristics of the individualised society, notably private and public, plurality and differentiation, stigmatising and social inequality, economising of the society and experience of space and time. People want to be treated for who they are and as individuals. Although this position is very much relativistic, it challenges practical theology to have a deeper understanding of a changing society.

Dillen (2015: 69-80) argues that the reference to practical theology as theological reflection on the practice, experience and attitude of people, is too narrow to cover the scope of practical theology for what it really is. She presents instead an integrated understanding of pastoral theology having three domains, namely church, society, and academia. Academia can be interpreted as practical theology as science. These dimensions relate to the question to whom the theological reflection is aimed at. Her approach is directed at the dialogue between these dimensions. The focus of practical theology cannot be narrowed down to the typical questions asked relevant for the church community only but should also comprehend the more complex development in society and how a church community should be guided to deal with these developments. In addition, the space of practical theology is even broader as it can extend advise to a community broader than the faith community only on what can be beneficial to society and its institutions. Within these grouping of institutions can it be expected to have faith communities that are broader than institutional church communities. This value addition is well illustrated through her observation that the church and / or Christian communities can request practical theology to guide them in developing new pastoral modes and approaches whilst society can request practical theology to guide what contribution religion and faith can make towards societal cohesion. Dames (2017:4) correctly argues in favour of a practical theology to address "the complex challenges of our time".

The value of this orientation is that the workplace is a study focus for practical theology. Based on Dillen's approach, the practice of workplace spirituality should be studied by practical theology whereafter practical theology can develop a faith-based approach to spirituality. This can be useful to understand the construct and practice of faith-based workplace spirituality without the one faith tradition dominating over the other. In this approach to workplace spirituality in a diverse workplace, can guiding topics such as meeting the individual other in the workplace regardless religion and faith, sustainability of the working environment and business, ethics and integrity, prosperity without becoming victim of possession and building the values of the organisation be the focus of practical theology. With this focus the claim is that practical theology is not only to serve the religion and faith orientations of one group only, for example the Christian community, but also to guide a community how to interact and work along with society in general. This means by implication that practical theology can assist both church and society on the meaning and value of workplace spirituality.

Schutte (2016: 4) adds a meaningful input to this discussion. He refers to Douglas Hick's concept of 'respectful pluralism' which indicates "the diversity of religions, philosophies and orientations in the workplace". This should be acknowledged and cannot be avoided in the workplace. Schutte continues to say that spirituality is inherent to a person and cannot be ignored in human life or work. Workplace spirituality is therefore also about the respect for a person as an employee and that employees are not part of the production line. Hence workplace spirituality is an end in itself because of human nature's needs and not a means to organisational productivity. The importance of his observations is to underline and uphold humanity in a changing working environment. The acknowledgement thereof and engagement with the interlink between humanity and working environment is core to a responsive practical theology.

Moving from this link between practical theology and workplace spirituality, is the question now how should practical theology approach workplace spirituality?

6. The approach of practical theology to workplace spirituality

From the perspectives in the previous section of this study, three interpretations are:

• Workplace spirituality is different from religion although it should not be separated from religion.

• The aim of workplace spirituality is the spiritual growth and development of employees which creates purpose, meaning and community.

• Practical theology can interpret the meaning of the workplace for the faith-based community and can direct what contribution religion and faith can make towards societal cohesion.

These perspectives are aligned with Dillen's view of the scope of practical theology as the dialogue between church, society, and academia (see paragraph 5 above).

Given these interwoven perspectives, three significant roles for practical theology in workplace spirituality are (a) contributing towards the promotion of workplace pluralism, hence community as a lead principle in workplace spirituality; (b) finding purpose and meaning as self-efficacy within the workplace and (c) developing of body of knowledge on workplace spirituality.

The first two roles can be further shaped by Burggraeve's approach to take responsibility for the individual other. Burggraeve, following Emanual Levinas, identifies the responsibility for oneself and the responsibility for the other person. Very often the "other" is unknown to us. He refers to these responsibilities respectively as first person and second person responsibility. The responsibility for the individual other is sparked by the engagement with another person. This engagement evokes the responsibility for the other individual. He continues to illustrate this engagement with and responsibility for the individual other by using the parable of the merciful Samaritan. Through this parable the point is well illustrated that engagement with the other challenges the situation of the unknown individual other, one's own prejudice and how to take charge of this second person responsibility together with a first-person responsibility (Burggraeve, 2021).

With this said, the approach practical theology can take towards workplace spirituality is to promote the first and second person responsibilities within the workplace based on religion and faith and to equip the church to guide the congregation how to deal with these responsibilities. This focus is aligned to Dillen's view of the scope of practical theology as the dialogue between church, society, and academia.

This perspective can be illustrated through healthcare. An appropriate example is the COVID-19 pandemic. Fisher, Suri and Carson (2022:1) asked the question "What comes next in the COVID-19 pandemic?" They comment that although the pandemic is not over yet, through collaboration and solidarity societies can "transition to a manageable endemic disease state sooner". As a result, the pandemic's impact can be mitigated. To bring an end to the pandemic, collective actions will be required. What must be added is how will societies prepare for similar future events. These comments are useful in the discussion on practical theology's contribution to workplace spirituality. Whilst respect for lives and improvement of health can be related to religious and faith traditions, the tragedy of suffering and death should be discussed within the workplace. Apart from the responsibility healthcare workers have towards the protection of their own lives (first person responsibility), their profession necessitates the responsibility towards the lives and health of other (second person responsibility).

For securing purpose, meaning and community in the workplace, health systems together with the relationship between healthcare workers and patients should improve. Kenny's (2022) plea for the paradigm shift to bring back care in healthcare can be the focus point. The context is to resist the current healthcare pipeline, not to replace human care with robots and to preserve humanity and dignity. She says: "Therefore, it is a moral imperative for us as healthcare providers to move beyond the business models, the barriers of complacency, the harsh work environments, and the incivility and back the "care" into caring. We need to be intentional about patient-centeredness" (Kenny, 2022:34).

7. Conclusion

In this study it was concluded that:

• Workplace spirituality is an established concept and acceptable approach in the workplace. In a pluralistic working environment workplace spirituality is regarded as more appropriate than religion as it can accommodate different religious orientations.

• It has been confirmed that workplace spirituality can add value to an organisation as employees feel connected to other employees and can link their job profiles to the broader workplace vision and mission strategies.

• Three dimensions are associated with workplace spirituality namely sense of purpose, meaning and community.

• On a conceptual level is workplace spirituality different from religion but not separated from religion. It is not replacing religion but can be a meaningful way to express personal faith.

• Workplace spirituality recognises religion, commitment to work, finding meaning in work and contribute to workplace.

• Institutions will perceive workplace spirituality different. The church can use this to guide their congregations how to behave in a pluralistic working environment without neglecting their faith in the workplace. Organisations can use workplace spirituality to prosper. They can also use workplace spirituality to unite a diverse workforce around sense of purpose, meaning and community.

• Practical theology can extend its focus on the habitus of the working congregation and their needs to grow pastoral care and preaching to focus on the congregation in the workplace.

References

Aravamudhan, N. R., & Khrishmaveni, R. 2014. Spirituality at Work Place - An Emerging Template for Organization Capacity Building? Purushartha, 7(1), 63-78. [ Links ]

Arkenberg, C. Lee, P., Evans, A. & Westcott, K. 2022. TMT Predictions. Deloitte Insights. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/pt/Documents/technology-media-telecommunications/TMTPredictions/tmt-predictions-2022/TMT-predictions-2022.pdf. Date of access: 11 April 2022. [ Links ]

Ashforth, B.E. & Pratt, M.G. 2003. Institutionalized Spirituality: An oxymoron? In Giacalone, R.A. and Jurkiewicz, C.L. (eds.). Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance. New York: M.E. Sharpe. [ Links ]

Bell, A. 2012. Spirituality at Work: An employee stress intervention for academics? International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(11), 68-82. [ Links ]

Benefiel, M. 2003. Irreconcilable foes? The discourse of spirituality and the discourse of organizational science. Organization, 10(2), 383-391. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508403010002012. [ Links ]

Benefiel, M., Fry, L.W., & Geigle, D. 2014. Spirituality and religion in the workplace: History, theory, and research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6(3), 175-187. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036597. [ Links ]

Bergunder, M. 2014. What is religion? The Unexplained Subject Matter of Religious Studies. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 26, 246-286. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700682-12341320. [ Links ]

BinBakr, M.B. & Ahmed, E.I. 2015. An Empirical Investigation of Faculty Members' Organizational Commitment in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. American Journal of Educational Research, 3(8), 10201026. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-3-8-12. [ Links ]

Brown, R.B. 2003. Organizational spirituality: The sceptic's version, Organization, 10(2), 393-400. [ Links ]

Burggraeve, R. 2021. Baarmoederlijkheid van mens en God vanuit het verhaal van de barmhartige Samaritaan. Antwerpen: Halewijn Uitgeverij. [ Links ]

Case, P. & Gosling, J. 2010. The spiritual organization: critical reflections on the instrumentality of workplace spirituality. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion, 7(4), 257-282. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2010.524727. [ Links ]

Chawla, V., & Guda, S. 2013. Workplace Spirituality as a Precursor to Relationship-Oriented Selling Characteristics. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(1), 63-73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1370-y. [ Links ]

Dames, G.E. 2017. Practical theology as embodiment of Christopraxis-servant leadership in Africa, HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 73(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i2.4364. [ Links ]

Delbecq, L.A. 1999. Christian Spirituality and Contemporary Business Leadership. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(4), 345-349. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819910282180. [ Links ]

Dillen, A. 2015. What is praktische theologie? In Gartner, S. & Dillen, A. Praktische theologie. Verkenningen aan de grens. Leuven: Uitgeverij LannooCampus. 69-95. [ Links ]

Eisler, R. & Montouori, A. 2003. The Human Side of Spirituality. In C. L. Giacalone, C.L. & Jurkiewicz, R.A., ed. Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance. New York: Armorok. p. 46-56. [ Links ]

Fisher, D., Suri, S. & Carson, G. 2022. What comes next in the COVID-19 pandemic? The Lancet. Correspondence. Published online 11 April 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00580-3. [ Links ]

Fourie, M. 2014. Spirituality in the workplace: An introductory overview. In Die Skriflig/In Luce Verbi, 48(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v48i1.1769. [ Links ]

Fry, L. W. 2003. Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. In Leadership Quarterly, 14(6), 693-727. https://doi.org/10.1016/jJeaqua.2003.09.001. [ Links ]

Fry, L.W., & Slocum, J.W. 2008. Maximizing the Triple Bottom Line through Spiritual Leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 37(1), 86-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2007.11.004. [ Links ]

Garcia-Zamor, J. 2003. Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance. Public Administration Review, 63(3), 355-363. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00295. [ Links ]

Gartner, S. 2015. Nieuwe grenzen. Over de laatmoderne context van praktische theologie, kerk en pastoraat. In Gartner, S. & Dillen, A. Praktische theologie. Verkenningen aan de grens. Leuven: Uitgeverij LannooCampus. p. 23- 43. [ Links ]

Geigle, D. 2012. Workplace Spirituality Empirical Research: A Literature Review. Business and Management Review, 2(10), 14-27. [ Links ]

Geybels, H. & Van Stichel, E. 2018. Weerbarstig geloof. Leuven: Acco. [ Links ]

Helminiak, D.A. 2006. The role of spirituality in formulating a theory of the psychology of religion. Zygon, 41(1), 197-224 [ Links ]

Houghton, J. D., Neck, C. P., & Krishnakumar, S. 2016. The what, why, and how of spirituality in the workplace revisited: a 14-year update and extension. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion, 13(3), 177-205. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2016.1185292. [ Links ]

Issa, T. & Pick, D. 2011. An interpretive mixed-methods analysis of ethics, spirituality and aesthetics in the Australian services sector. Business Ethics: A European Review, 20, 45-58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2010.01605.x. [ Links ]

Izak, M. 2012. Spiritual episteme: sensemaking in the framework of organizational spirituality. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 25(1), 24-47. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811211199583. [ Links ]

James, M.S., Miles, A.K. & Mullins, T. 2011. The interactive effects of spirituality and trait cynicism on citizenship and counterproductive work behaviors. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 8(2), 165-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2011.581814. [ Links ]

Karakas, F. 2010. Spirituality and performance in organizations: A literature review. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(1), 89-106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0251-5. [ Links ]

Kenny, D. 2022. Time for a Paradigm Shift: The Necessity for the Human Side of Patient Care. Journal of Health and Human Experience 8 (1): 23-40. [ Links ]

Kinjerski, V M., & Skrypnek, B.J. 2004. Defining spirit at work: finding common ground. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(1), 26-42. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810410511288. [ Links ]

Kolodinsky, R.W., Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C.L. 2008. Workplace values and outcomes: Exploring personal, organizational, and interactive workplace spirituality. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(2), 465480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9507-0. [ Links ]

Leigh, P. 1997. The new spirit at work. Training & Development, 51, 26-33. [ Links ]

Liu, C. & Robertson, P. 2011. Spirituality in the Workplace: Theory and Measurement. Journal of Management Inquiry, 20(1), 35-50. [ Links ]

Long, B. & Mills, J. 2011. Workplace Spirituality, Contested Meaning and the Culture of Organization: A critical sense-making account. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(3), 325-341. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811011049635. [ Links ]

Marques, J. F. 2006. The spiritual worker: An examination of the ripple effect that enhances quality of life in- and outside the work environment. Journal of Management Development, 25(9), 884-895. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710610692089. [ Links ]

McGhee, P. & Grant, P. 2008. Spirituality and Ethical Behaviour in the Workplace : Wishful Thinking or Authentic Reality. Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organizational Studies, 13(2), 61-69. [ Links ]

Milliman, J., Czaplewski, A.J., and Ferguson, J. 2003. Workplace Spirituality and Employee Work Attitudes. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 426-447. [ Links ]

Mitroff, I.I. & Denton, E.A. 1999. A study of spirituality in the workplace. Sloan Management Review Association, 40(4), 83-92. [ Links ]

Mohamed, M. & Ruth, A. 2016. Workplace spirituality and organizational commitment: A study on the public schools teachers in Menoufia (Egypt). African Journal of Business Management, 10(10), 247-255. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajbm2016.8031. [ Links ]

Mohan, D.L., & Uys, K. 2006. Towards living with meaning and purpose: spiritual perspectives of people at work. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 32(1), 53-59. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v32i1.228. [ Links ]

Naidoo, M. 2014. The potential of spiritual leadership in workplace spirituality. Koers - Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, 79(2). 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/koers.v79i2.2124. [ Links ]

Neal, J. & Biberman, J. 2003. Introduction: The leading edge in research on spirituality and organizations. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 363-366. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810310484127. [ Links ]

Nooralizad, R., Ghorchian, N. & Jaafari, P. 2011. A casual model depicting the influence of spiritual leadership and some organizational and individual variable on workplace spirituality. Advances in Management, 4, 14-20. [ Links ]

Pandey, A., Gupta, R. K., & Arora, A.P. 2009. Spiritual climate of business organizations and its impact on customers' experience. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(2), 313-332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9965-z. [ Links ]

Pashak, T.J. & Laughter, T.C. 2012. Measuring service mindedness and its relationship with spirituality and life satisfaction. College Student Journal, 46, 183-192. [ Links ]

Phipps, K.A. 2012. Spirituality and strategic leadership: The influence of spiritual beliefs on strategic decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 106, 177-189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0988-5. [ Links ]

Prior, M.K. & Quinn, A.S. 2012. The relationship between spirituality and social justice advocacy: Attitudes of social work students. Journal of Religion and Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 31, 172-192. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2012.647965. [ Links ]

Rathee, R. & Rajain, P. 2020. Workplace Spirituality: A Comparative Study of Various Models. Jindal Journal of Business Research, 9(1), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278682120908554. [ Links ]

Sass, J.S. 2000. Characterizing organizational spirituality: An organizational communication culture approach. Communication Studies, 51(3), 195-217. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510970009388520. [ Links ]

Schutte, P.J.W. 2016. Workplace spirituality: A tool or a trend? HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies, 72(4).1-5. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i4.3294. [ Links ]

Sorakraikitikul, M. & Siengthai, S. (2014). Organizational Learning Culture and Workplace Spirituality: Is Knowledge- sharing behavior a missing link? The Learning Organization, 21(3), 175-192. https://doi.org/10.1108/tlo-08-2011-0046. [ Links ]

Steenkamp, P.L. & Basson, J.S. (2013). A meaningful workplace: Framework, space and context. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies, 69(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v69i1.1258. [ Links ]

Tagavi, L. & Janani, H. 2014. The Relationship between Workplace Spirituality and the Organizational Climate of Physical Education Teachers in the City of Tabriz. Indian Journal of Applied and Life Sciences, 4(53), 969-973. [ Links ]

Tolentino, R.C. 2013. Organizational Commitment and Job Performance of the Academic and Administrative Personnel. International Journal of Information Technology and Business Management, 75(1), 51-59. [ Links ]

Ulrich, D. & Ulrich, W. 2010. The Why of Work. New York: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, F. & De Klerk, J.J. 2014. Workplace spirituality and job satisfaction. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(3), 379-389. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, F. & Steyn, P. 2019. Workplace spirituality and the ethical behaviour of project managers. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 45, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v45i0.1687. [ Links ]

Van Tonder, C. L. & Ramdass, P. 2009. A spirited workplace: Employee perspectives on the meaning of workplace spirituality. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 7(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v7i1.207. [ Links ]

Wagner-Marsh, F. & Conely, J. 1999. The fourth wave: the spiritually-based firm. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 72(4), 292-301. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819910282135. [ Links ]

Wahid, N.K.A. & Mustamil, N.M. 2014. Communities of practice, workplace spirituality, and knowledge sharing: The mind and the soul. International Conference on Technology and Business Management. March 24-26. [ Links ]

Wainaina, L., Iravo, M. & Waititu, A. 2014. Effect of employee participation in decision-making on the organizational commitment amongst academic staff in the private and public universities in Kenya. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 3(12), 131-142. [ Links ]

Wilson, F. (2013). Organizational Behaviour and Work: A critical introduction (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Laetus OK Lategan

llategan@cut.ac.za

Published: 1 September 2022