Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Koers

On-line version ISSN 2304-8557

Print version ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.85 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.85.1.2477

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Archaeology of time - activation of installation space by the spect-actor

Ho epolloa ha lintho tsa khale nako: ts'ebetso ea sebaka sa tlhomamiso ke moetsi oa spect-actor

Janine LewisI; Jan van der MerweII

IDepartment of Performing Arts Tshwane University of Technologyhttps://orcid.org/0000-0002-3681-567X

IIDepartment of Fine & Studio Art Tshwane University of Technologyhttps://orcid.org/0000-0003-2125-466X

ABSTRACT

An artistic installation implies theatre in situ, in that a/the space is transformed into a potential experiential encounter through design and scenography. This potential space then only requires the spectator to activate the full experience through embodied engagement with the installation, inciting visceral meaning-making. This embodied activation implies that the spectator then also becomes a performer, as they are simultaneously the ones physically causing the theatrical experience and the ones experiencing the elements designed for (their) interpretation. In this manner a heightened sense of becoming what Boal (1992) coined the 'spect-actor' is achieved By activating the space through physical engagement with/in the installation where all the sensory receptors trigger a visceral response in the spect-actor, meaning-making occurs through phenomenology and implies a knowing body through personal- and socio-cultural interpretation. For this paper, the installations by renowned South African artist Jan van der Merwe are used as examples to argue for the emergence of the spect-actor in the role of activator. As an installation artist, Van der Merwe creates large artworks of intricately recreated tableaux often composed in discarded, rusted found material. Van der Merwe calls the found objects "artefacts of our time". Thus, they assume an archaeological quality and become relics of a way of life, a civilisation degenerated and fossilised though time and rust. The spect-actor is both then the site and cite of activation where the time and space converge into an ephemeral experience.

Keywords: Installation art, Jan van der Merwe, embodied perception, spect-actor

KHOTSO

Boetsi ba bonono bo ikhethileng ka tshebediso ya ditshwantsho sebakeng ho bontša hore ho na le liketsahalo tsa sethala, ka hore sebaka se fetoha sebopeho se nang le phihlelo ka ho qaptjoa le ho shebahala. Sebaka sena se ka etsahala habonolo feela se hloka hore mmoheli a khone ho etsa boiphihlelo bo feletseng ka ho khomahanya ka ketsahatso, e leng tsela ya ho khothalletsa ho etsa moelelo oa visceral. Tshebetso ena e ncha e fana ka maikutlo a hore motho ea shebellang le ena o fetoha sebapali, kaha ka nako e tšoanang o etsa hore ho be le boiphihlelo ba papali ho ba nang le likarolo tse etselitsoeng tlhaloso ea bona. Ka tsela ena ho ba le kutloisiso e phahameng ea ho ba seo Boal (1992) a ileng a se bitsa hore ke mmohi-sebapali se fihlelloe. Ka ho futhumatsa sebaka ka tsela ya ho sebelisa mmele har'a mosebetsi wa bonono o pampiri ena e baung ka ona, e leng ona o lokollang li-receptor tsohle tse utloahalang hore li hlahise karabo ea visceral ho mmohi-sepali. Ho etsa moelelo o etsahalang ka phenomenology ho bolela mmele o tsebang ka litlhaloso tsa setso. Bakeng sa pampiri ena mesebetsi ea bonono ea moetsahatsi oa Afrika Boroa ea tummeng, Jan van der Merwe, e tla sebelisoa e le mohlala ho pheha khang ka ho hlaha ha mmohi-sebapali karolong ea motho ea futhumatsang le ho etsahatsa mosebetsi wa bonono ka nako eo o etsahalang ka yona. Joalokaha moetsahatsi oa bonono, van der Merwe o etsa litšoantšo tse kholo tsa sekalitšoantšo tse entsoeng ka mokhoa o rarahaneng o atisang ho etsoa ka thepa e lahliloeng, e bolileng. Van der Merwe o bitsa lintho tse a lifumaneng ho etsa mosebetsi oa hae "lintho tsa nako ea rona". Ka hona, ntho tsena linka seemo sa lintho tsa khale tse epollotsoeng ebe lifetoha litšoantšo tsa mokhoa oa bophelo, tsoelo-pele e ileng ea khutlela moraho le ho khitloa nakong. Ha hole joalo, mmohi-sepabali eba sebaka le moetsahatsi wa futhumatso tsebetsong moo nako le sebaka li fetohang phihlelo ea ho iphelisa.

Installation art has an established history that spans the twentieth century and is firmly rooted in the twenty-first century. According to De Oliveira, Oxley and Pety (2003), over the last decade installation art has achieved mainstream status within contemporary visual culture and has given rise to new terms and affected not just art but also fashion, movie design, and club culture. Theatre has also embraced the sites of installation performances with such works being coined as 'immersive theatre' that include works such as created by the British Punch-Drunk company. "The new 'immersive' installation reflects a desire for sensual pleasure, as the viewer is totally enveloped in a hermetic and narcissistic artwork... The culmination of these processes has made the audience itself the key site of the Installation" (DeOliveira et al., 2003: ii).

Leading up to these developments has included the realisation of the importance of the spectator's role in engaging with the installation. Artworks such as paintings can exist beyond the need for interaction or participation from a/the viewer, but an installation is stimulated by, or in turn stimulates the site and space in which the installation is created and requires activation through embodied involvement by the spectator to fully awaken visceral or meaning-making value. The spectator needs to engage: walk into/onto/amongst, intimately witness and intuitively experience; and only though this activation does the artwork truly come alive.

The installation exists in space until the moment of activation, and each spectator's (re) action to the space enlivens the artefact and makes for meaning interpretation. For this article, installation artworks are used as the focus of interpretation as sites/cites for sensory embodiment by the spectator. Works by renowned South African artist Jan van der Merwe are used as examples to argue for the emergence of the spectator in the role of activator of installation artworks.

1. Installation art

Installation art can be described as a dialogue between the artist and space. Although this strategy is often viewed as a recent (1970 onwards) development in the visual arts (Bishop, 2005: 8), it springs in fact from a very long tradition of cave painting, religious art and architecture where space is manipulated to convey meaning. In this manner, a/the space for the installation is transformed into a potential experiential happening through the art of representing objects in perspective, especially as applied in the aspects of design. Where, "a gallery has ceased its conventional activity of showing objects and become a place to experience experience" (Archer,1994: 29).

The genre of installation has proved to be useful by which to rhetorically speak of and investigate life, where the installation artist has become a means to reflect the experience of life - its complex issues, aspects, and appearances (Rosenthal, 2003: 27). The installation is tangible in space and yet evokes a sense of the ephemeral nature of the theatrical when activated by a spectator who experiences it through time. This renders the installation design as potential scenography1. This heightened theatrical space requires the spectator to activate the full experience through embodied engagement with the installation and by meaning-making. This activation implies that the spectator then also becomes an active participant (a performer or actor2 in the theatrical experience if you will) as they are simultaneously the ones physically causing the experience and the ones experiencing the elements designed for their interpretation. In this manner a heightened sense of becoming what Boal (1992) coined the "spect-actor" is achieved - where the provocative artwork elicits activation from a personal- and socio-cultural association in such a way as to cause a sensory experience which triggers meaning-making and may further cause discussion and debate with other spect-actors3. The spectator is "transformed into a protagonist in the action, a 'spect-actor', without ever being aware of it. [S]he is the protagonist of the reality [s]he sees (Boal, 1992: 241). The "spect-Actor is not fictional. [S]he exists in the scene and outside of it, in dual reality in this way the spectator becoming the Spect-actor is democratically opposed to the other members of the audience, free to invade the scene and appropriate the power of the actor" (Boal, 1974: xx- xxi). This is akin to Goffman's (1981; Burns, 1999) philosophy that we as humans are all actors (Laitman & Ulianov, 2011: 156).

In opposition to the ideological gaze associated with a cinema audience, within theatre, the nature of the production-reception relationship remains an investigation. Bennet (1997: 86-87) further suggests that:

... the energies of theatre semiotics have not resulted in a codification of the elements of theatrical practice but have established the multiplicity of signifying systems involved and the audience role of decoding these systems in combination and simultaneously. Neither theories of reading nor theatre semiotics, however, goes far beyond the issues of facing an apparently individual subjectivity. Neither takes much notice of reception as a politically implicated act.

In this article, however, it is not the intent to explore installation art as theatrical. Therefore, the references to the relationship between production and reception in such a context (attitude toward/perception of/relationship offering potential social interaction), or positioned within and against cultural values (Bennett, 1997: 86) is not the focus of the investigation. However, the perception of spectators within a performative context in which they may interact and/or participate as a potential 'actor' or activator is relevant, especially the individual's subjective responses to the interaction. Also, Coppieters' (1981) four conclusions about aspects of audience perception are considered, the third one entailing objects is pertinent toward installation art: "Inanimate objects can be personified and/or receive such strongly symbolic loadings that any anxiety about their fate becomes a crux in people's emotional experience".

As Merleau-Ponty (1964) states: a spectator as human cannot look at the artwork and separate it from their lived experience of the world, the installation exists in the spectator's perception of it. Therefore, it can be concluded that a spect-actors' activation of an installation reflexive artwork is a phenomenological one. Merleau-Ponty further quotes Cézannne in that "nature is inside us" and clarifies this from his philosophical vantage point by adding "quality, light, colour, depth, which are all before us, are there only because they awaken an echo in our body and the body welcomes them" (Merleu-Ponty, 1964: 164). Hustvedt (2013), in turn, describes this phenomenon as 'art as a memory' where "Every painting is always two paintings: the one you [the spectator] see, and the one you remember". DeOliveira (2003: 213) comments on memory as: "In a rapidly changing world, time and memory become key concerns... where spaces of memory may be constructed". Hustvedt (2012: 213) further advocates the first-person experience as:

[The first-person experience is] an embodied one. I [the spectator] don't only bring my eyes or my intellectual faculties or my emotions to a picture. I bring my whole self with its whole story. The relation then is between an I and an it and partakes of the artist's being as well, his entire being, which is why we treat art in a different way to utilitarian objects like forks.

Rosenthal (2003: 28) proposes a classification of installation art with four poles: enchantments and impersonations (filled-space installations), and interventions and rapprochements (site-specific installations). Van der Merwe's installations can be situated within these strategies, especially with reference to filled-space installations.

2. Jan van der Merwe's installation art

South African artist, Jan van der Merwe, is celebrated for his installations in which he incorporates found objects with rusted tins. Many artists work in the field of objét trouvet - the 'found object' where the 'rescue' items are salvaged from being dumped or, ironically, from being properly used, only to re-assign such objects as works of art. In Van der Merwe's case, it is not the object, but spoilt rusted matter littering the countryside that is found and redefined. Through time, oxidation and deterioration occur, these rusted tins and items became discarded by everyone as unusable and undesirable. Through deftness and patience, befitting an accomplished weaver, Van der Merwe reformulates these unlikely materials into desirable 'textiles' and surfaces, finally to 'stitch and sew' them into garments and objects of deeper significance.

Material carries metaphorical meaning in contemporary art. Since Picasso introduced collage as fragment of real life into art at the beginning of the 20th century, the range of materials utilised by artists has opened up and the choice of materials and technique has become arbitrary, often depending on the meaning the artist intends to convey. The choice of materials is very specific in Van der Merwe's artwork. Working primarily in rusted metal, Van der Merwe has developed a language that speaks subtly yet eloquently of the South African psyche. Often his inspiration is drawn from highly personal sources to develop themes that can be universally appreciated but more intensely so by viewers familiar with the peculiarities of South Africa - its art, society and history. Van der Merwe often refers to his work as 'monuments'. Like conventional monuments some of the installations impose on a significant amount of space and the viewer is enticed to step up or step into/onto/ amongst and towards the installation for closer examination. These 'monuments' are anonymous or broadly universal; they refer to the memory of the unknown by many. The installations seem like abandoned film sets without actors.

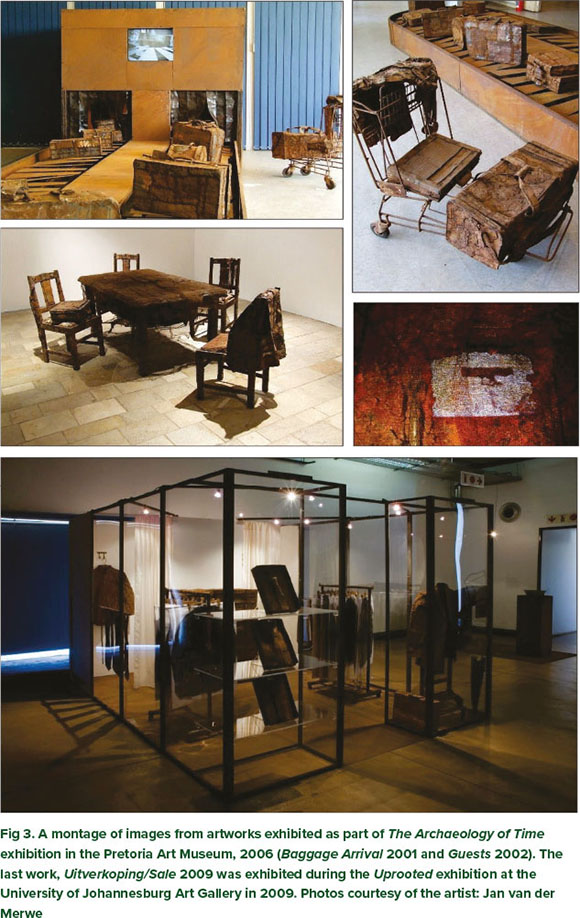

Several of Van der Merwe's installations juxtapose public spaces with private spaces. Examples of installations where intimate or private and public spaces are played off against each other include Baggage Arrival, 2001 - the carousel with baggage is a public space where passengers gather, but the bags and suitcases contain their personal belongings and is private property, and Guests/ Gaste, 2000 - a dining room table with four chairs. In the table surface are four television monitors (almost like place mats or plates) with the audio-visual image of a repetitive gunshot. The private space of the family dining room is invaded by violence or pressures from society outside of the home. Uitverkoping/Sale, 2009 represents a men's clothing shop. The space of the shop is public, but the moment the spectator enters the curtained fitting room, the space becomes private.

Van der Merwe's working process is also significant. He describes himself as a compulsive collector who takes objects discarded by others to his studio where it could be transformed into part of his installations. The tins that he collects are sometimes already rusted; but if received still new and shiny, Van der Merwe transforms them by initiating the rust process with a mixture of salt, water and vinegar. He covers the large solid objects such as furniture with the rusted tins using small nails. Clothing is created in a process like sewing where he attaches each piece of tin to the next with thin wire and the final finish is created by adding bitumen4 and sand to create smooth transitions from one part to the next. This technique allows the artist to 'shift time', rendering the objects into 'archaeological finds'.

At present I work with artefacts of our time and attempt to transform them into archaeological remnants... The tin cans are ordinarily used for preservation. The fragile rusted tins in these works become metaphors for waste, loss and consumerism. Their use may be seen as an attempt to 'preserve' something transient and vulnerable (van der Merwe, 2011).

Van der Merwe may also make use of technology in his art works that becomes part of the archaeology. Images viewed on a screen are second-hand experiences to the viewer, yet evoke a visceral response to a first-hand memory or intrinsic knowing. There is a contrast between the tactile experience of the visitor to the installation (the emphasis on texture and the many real mundane objects) and the images viewed on screen - the contrast between the real and illusion. To Van der Merwe, images projected on screen also have a spiritual quality, where, as humans, people have developed technology to assist in the study and (re) discovery of ancient origins and to search the unknown such as in deep space. Perhaps this need for study and discovery mirrors a spiritual quest that is symbolised by the illusionary quality brought to the installations through technology.

3. Immersive installation activation: Die Einde/The End, 2006

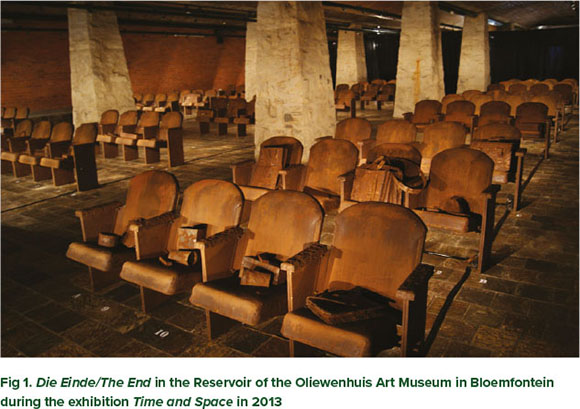

Delving into the immersive nature of the spect-actor's experience, emphasis is placed on the installation: Die Einde/The End. This installation was exhibited for the first time in 2006 in the Albert Werth Hall in the Pretoria Art Museum during the retrospective exhibition entitled The Archaeology of Time, and for the second time in the Reservoir of the Oliewenhuis Art Museum in Bloemfontein during the exhibition Time and Space in 2013.

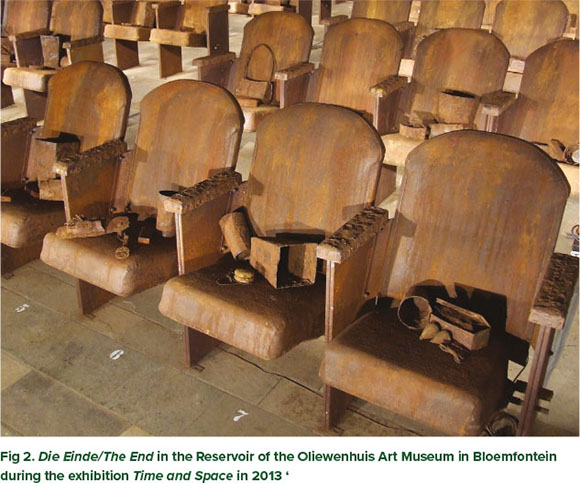

The exhibition space/s that contained the installation Die Einde/The End were transformed to resemble a film theatre and comprise a hundred and eight film theatre chairs arranged in rows. On the seats of the chairs are various individuals' personal belongings: hats, gloves, handbags, purses, spectacle cases, keys, briefcases - all representing ordinary people. The objects contain the lives of their owners. These objects allude to people, but the people themselves are absent, as if they have left their belongings behind in the theatre. All the objects are covered in rusted metal, and appear frozen in time, creating a sense or awareness of absence.

This rusted patina as a method by means of which contemporary objects are placed into 'archaeological time', and while it may have a nostalgic effect on the spect-actor, forces the spect-actor to consider, scrutinise and respect contemporary life, especially the ordinary. The commercial metal tin is ordinarily used to preserve food, in this case an attempt is made to 'preserve' vulnerability and transience. The use of rusted tins in this installation is a further metaphor for recycling - to rust is to go back to the original matter, the end of a process and the start of the new. Also notable is that the chemical process of rust is a physical battle against time, which is in contrast to the preservation and (re)cyclical interpretations of time alluded to in the installation.

The placement of the chairs in rows is suggestive of the layout of old graveyards, with separate spaces dedicated to children, soldiers and ordinary citizens. The backs of the chairs resemble gravestones, emphasised by the order of the layout and the markings and decay on their surfaces like the marks left by water and the elements through the passing of time, on gravestones. Each chair in this installation becomes a monument to the ordinary and represents the faceless, the unknown with his/her personal struggles, and references the human struggle against natural forces which are overpowering, such as: war, disease, and power. The visitor to an old graveyard is gripped by nostalgia and is aware of emotions effected by loss, the passing of time and an awareness of vulnerability - the artwork attempts to echo these ephemeral qualities. This installation may be viewed as an opportunity to reflect - a monument to anonymous people.

4. Van der Merwe's intended activation of Die Einde/The End

When the filmgoer enters a movie theatre, he/she enters a public space, but the moment the lights dim, and the film begins, the experience becomes private and personal. In this installation, the spect-actor, now in the role of filmgoer-viewer who enters the already darkened space from the back of the 'theatre', is momentarily blinded by 108 small lights, attached to the back of each chair, dimly lighting the objects on the chair in the parallel row directly behind them. The lights also resemble stars in a dark sky and transport the viewer to an imaginative space. When the spect-actors eyes adjust to the barely lit room, the installation becomes visible. As the viewer moves to the front of the installation and looks back, the lights at the back of the chairs are invisible, but the objects and chairs are bathed in soft light resembling the dim effect of sunrise. This light effect suggests the contrasts between day and night, darkness and light.

The layout of the objects echoes the conventions in old bioscopes where children sat in the front, and there is a block for adults and for soldiers; but also, as mentioned, the work as a whole resembles a graveyard with designated sections. The spect-actor can walk between the rows of seats and can see the seat numbers stencilled on the floor. The 'journey' between the rows of seats resembles a walk in a maize or a pilgrimage with stations. The objects on the seats are remnants or evidence of lives and suggest units like frozen film frames where private, personal narratives unfold.

The spect-actor moves slowly among the rows and looks down to inspect the objects on the seats. In the last row at the back is a chair with a notebook on the seat and a jacket draped over the back, as if left behind by a film critic. Van der Merwe dedicated this chair to the memory of South African art and theatre critic, Barrie Hough (1953-2004). In row 9, on the 11th chair lies two folded 'paper' planes, made of rusted metal - a reference to the violence and loss of the American terror attack events of 11 September 2001. Although there is an allusion to the outside world and disaster on a global scale, a personal memory is also evoked by the inclusion of such items as intimate and fragile toys of a young child. These objects are also dedicated to a specific young family member who lost his life at a very young age and who left a memory of a game with two toy aeroplanes, and thus also has a strong visceral sensory memory of a specific person. The knowledge of these literal connections is, however, not revealed to the spect-actor. Their relevance is to the evoked interpretation, both from the sincere and insightful handling by the artist, to the reflective reception induced in a spect-actor.

As in a film theatre the chairs are placed viewing a large screen. Footage consisting of a continuous loop of images of various versions of the words 'the end', indicative of the endings of films in various fonts and sizes, is projected onto the screen and forms the only luminous lighting in the installation, cascading between bright illumination and more muted tones. The use of multiple fonts contributes to a sense of diversity and adds to the universality of the installation. The repetition of the words, as with the repetitive pattern formed by the chairs, and the decay and aura of decomposition may also suggest cycles: in history and in human lives.

This installation uses pop culture (where the cinema and Hollywood culture are conjured) as a metaphor, but the outward glossy layer that is typical of popular culture is stripped away to reveal the decay underneath, or it may refer to something more spiritual than the ephemeral world of pop culture. In a sense the fault line between the real and the illusionary is the focal point of this work: that experience of all moviegoers when the make-believe is shattered by the words: The End and the real world has to be faced. The end is also the beginning of the real.

5. Spect-actors' embodied activation in Van der Merwe's installation art

Being intrigued by the audience/performer relationship in experiential and theatrical spaces, performance-maker Lewis keenly reflected and observed general public's (re) actions as a visitor and observer during Van der Merwe's The Archaeology of Time exhibition in the Pretoria Art Museum in 2006.

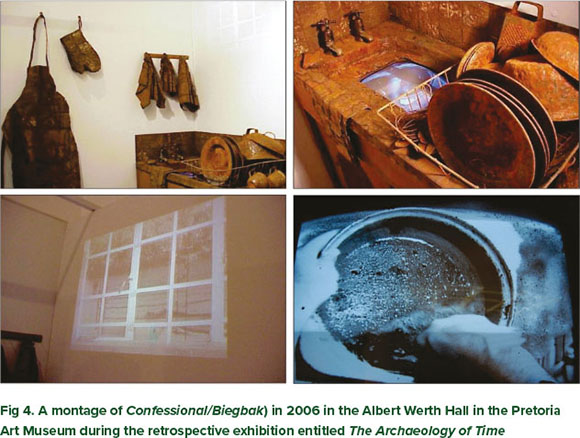

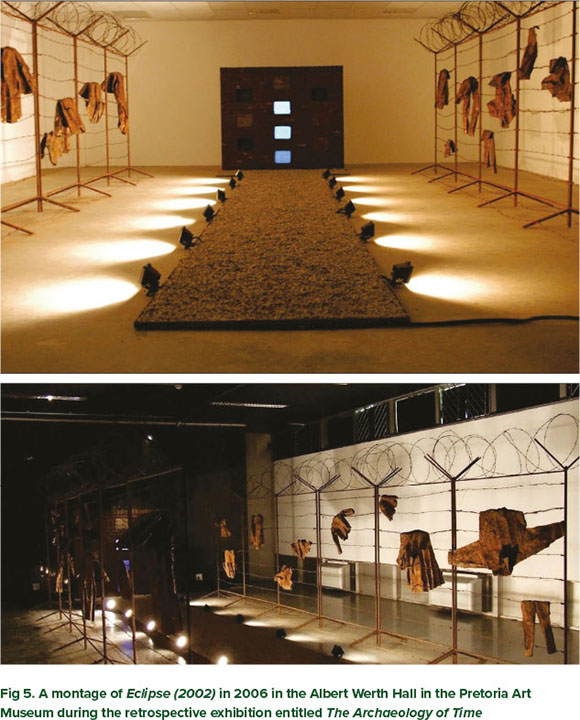

The section that follows is reflexive and reflective, and includes ex-post facto data gathering, where a random sampling of the visitors who attended the exhibition were interviewed. It was a first first-hand experience of installation art for some of the visitors, and the often-unexpected adaptation of spaces was also new to all public present. The transition from mere viewing spectators into the role of witnessing and activating spect-actors was perceptible. Noticeable role acquisition was especially evident with reference to these installations at the exhibition: Confessional/Biegbak (2003), Eclipse (2002), and Die Einde/The End (2006).

To frame the understanding of the observed experiential visceral responses, it is helpful to frame these experiences within a framework of three artworks. As with all Van der Merwe's installations, these three were striking in their simplicity yet provoked profound individual responses. Die Einde/The End has been detailed above, and the activation by spect-actors is discussed later. The other two installations Confessional/Biegbak 2003, and Eclipse 2002 are described below.

Confessional/Biegbak (2003) is installed in the corner of the exhibition space and 'walled' and 'curtained' off so that the viewer must enter a small room. Inside a kitchen sink (basin) with dishes, dish cloths, oven gloves and an apron all covered in rusted tin are seen. Built into the basin is a television monitor with the image of hands continuously cleaning a pot and above the sink is the projected image of a window through which rain on a courtyard is visible. The audio-visual images are intended to lend a nostalgic atmosphere to the work and refer to repetitive processes in nature and in everyday rituals.

Van der Merwe here comments on the fact that each generation 'cleans up' and tries to start afresh; the cleaning or purifying ritual can also have religious connotations. In contrast to this private experience, Eclipse (2002) reflects a very public space. A grave side is represented as an altar at an end of a long avenue of white gravel stones laid out as a pathway between temporary fencing with barbed wire across the top, the type of wire often used by police or security to enforce crowd control measures. There are articles of military uniforms covered in rusted tin littered against the fencing, almost as if they had been flung there, or were caught in a net. These represent many soldiers whose lives have been lost in the line of duty. The stark flood lighting focussed on the fencing deliberately alludes to exposing and shedding light on aspects that require interrogation.

The individual spect-actors approached the confessional installation and ventured in, beyond the small curtain, and those that have stood and washed dishes at the kitchen sink, found themselves in a familiar position where they were met with a memory jogged by physical activation of moments spent in reconsideration and reflection. The enclosed room becomes, for a time, a small personal and poetic space. As a spectator, the visceral response generated from the physical embodied memory of time/s spent in such a position is further enhanced by the reality of the situation, where the 'actor' is (re)assuming a familiar role, and reflecting on the reflections of their memories. The realisation also is further impacted when the spect-actor is faced with the symbolism found in the title Confessional/Biegbak, and even if they have never literally experienced being in a catholic confessional booth (and if they have, this compounded the experience), they certainly can attest to the reflective emotional engagement they have with the intimate private space - a spiritual experience. When the spect-actors emerged, their demeanour and expression had changed. Many had a sense of calmness and expressed a wistful gaze. Some were quite emotional and spent almost as much time outside the booth in quiet contemplation as they had inside. The personal experiences and emotional memories were engaged through the embodied activation of the space.

Eclipse being a more public environment allowed for a more comprehensive observation of the spect-actor's reactions. The installation elicited interaction. All who entered the space needed to approach the altar situated at the far end, and to do so they naturally followed the pathway set out for them. This is where the activation and role-play took place. Many spectators 'arrived' at the space jovial and chatty with their contemporaries, some ventured swiftly onto the gravel pathway, others less rushed, but invariably all slowed down. The physical feeling of the crunching stones beneath their feet, as well as the sound it created seemed to have a mesmerising effect on all who encountered it - through a heightening of their senses, changing these spectators into active participants in the experience, and causing them to slow down the time of viewing and focus on their environment. Some spectators stopped before they encountered the pathway and one could observe the deliberation they were having within themselves, deciding whether or not they felt they could/should invade the 'privacy' of this public space. Some of these deliberators respectfully waited for others to finish their interaction with the installation, rendering them witnesses to the experience, before they began to participate and ventured on the gravel pathway. Only a few chose to walk alongside the gravel. These spect-actors that walked alongside the gravel walked faster than their counterparts and often rushed to the end and quickly returned, all the while being hunch over and exuding almost a guilty or 'I'm sorry' expression. For these, it may have been the interrogatory lights caused a different role to be assumed, and they did not experience or take as much reflective time at the altar as those spect-actors who had walked along the gravel.

6. Spect-actor's embodied activation of Die Einde/The End

As an active participant in the installation, Lewis entered the Die Einde/The End and experienced the initial feeling of arriving late at the cinema where the film had already started, generating a sense of wanting to apologetically quickly find your seat without too much disturbance. Fighting this urge to move through the dark cinema, she hung back in the darkness until her eyes had acclimatised to the sparse lighting, during which time the awareness of the silence despite the flickering screen became numbing. This silence is the opposite of a conventional cinema experience where the surround sound is key. The only sounds that could be heard came from the hushed rustling movements of other participants in the installation, reminiscent of audience members in a public arena, making the environment more 'real'.

During the build-up to the exhibition, Lewis had discussions about the preparation process with Van der Merwe and was therefore aware that the seats had been repurposed from an old theatre that had been refurbished. Having frequented the original theatre, this new experience of the installation was impacted by the memory of the original seating arrangement and a sensory memory generated the desire for Lewis to return to the familiar seat to find comfort and assure a safe vantage point. These sensations soon gave rise to the nostalgia of the overall experience in the space and a palpable sense of loss and longing.

As spect-actors entered and exited the playing space all contributed to the ensemble, everyone's initial (re)action giving way to a shared experience. Nobody could really make eye-contact in the dim light, but each person's simultaneous presence and absence could be felt. The spect-actors assumed the roles of the humans that were absent in the space. The passing between the rows caused the physical moving bodies to block out the small lights behind the chairs, casting shadows that added to the witness experience for other spect-actors in the room. The spatial-relationship the individual spect-actor had with the seating, and within the need to pass between the rows allowed for personal narratives to be formed and alliances made. Through immersion, these relationships of shared experience and intertwined visceral knowing was eternally forged between both the spect-actors and the objects as well as between each other.

7. Conclusion

As spectators of artwork (performance or design), one's personal cultural experiences and memories influence one's perceptions, but when that perception is disrupted by active experiential involvement there is an overwhelming embodied, visceral, sensory flooding. The activation of installations as theatre by association invokes: "the only place where the mind can be reached through the organs and ... understanding can only be awakened through our senses" (Artaud, 1977).

Activation, through participation and involvement places the spectator in the role as an active participant in the art-making, an actor who is both creating and recreating simultaneously. The combination of the two aspects (spectator and actor) to form a spect-actor is both inevitable and vital for installation art to fully be activated, and the culmination of immersion into the artwork is unavoidable. However, there is a subtle difference between creating an artwork deliberately geared for the spectator to immerse themselves in; or creating an artwork that triggers a need or willingness to engage on the part of the spectator to experience the reflections of life from the artists vantage point. The space for the spectator to find themselves submerged in their own personal-cultural grappling's of the situation from their own vantage point of the slice of life presented. The first immersive stance allows for a wallowing or narcissistic interaction that implies a sense of control over the process by the spect-actor. The second implies an unwitting participation and experience where there is no objective control over the (re)actions the involvement will elicit. In installation artworks it is the later that needs to be activated, where there is no intentional manipulation of the emotional outcome which may be argued to be intentional within a truly theatrical experience.

The only conscious decision on the part of the spectator is to assume an active role, take part, and be the participatory actor in anonymity. The resulting spect-actor concretises the experience. Inside the spect-actor the work lives in different ways, and the work of art they carry around with them is a further and continued memory or an imprint of the emotional recall from the embodied activation.

Works cited

Artaud, A. 1977. The Theatre and Its Double. 2nd ed. London: John Calder Publishers Ltd. [ Links ]

Bennett, S. 1997. Theatre Audiences: a Theory of Production and Reception. 1st ed. Oxon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bishop, C. 2005. Installation Art: A critical History. London: Tate Publishing. [ Links ]

Boal, A. 1974. Theatre of the Oppressed. English ed. London: Pluto Press. [ Links ]

Boal, A. 1992. Games for Actors and Non-Actors. 1st ed. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Burns, T. 1999. Erving Goffman. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Channel, L. 2013. Art is a Memory [Interview] (13 May 2013). [ Links ]

Coppieters, F. 1981. Performance and Perception. Poetics Today, 2(3), pp. 35-38. [ Links ]

DeOliveira, N., Oxley, N. & Pety, M. 2003. Installation Art in the New Millennium. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. [ Links ]

Goffman, E., 1981. Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [ Links ]

Hustvedt, S., 2012. Living, Thinking, Looking. London: Hodder & Stroughton Ltd. [ Links ]

Laitman, M. & Ulianov, A. 2011. The Psychology of the Integral Society. Cape Town: Laitman Kabbalah Publishers. [ Links ]

Merleau-Ponty, M. 1964. Eye and Mind. In: J. Wild, ed. The Primacy of Perception. Chicago: Northwest University Press. [ Links ]

Rosenthal, M. 2003. Understanding Installation art: from Duchamp to Holzer. New York & London: Prestel. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, J. & Lewis, J. 2011. Archaeology of Time - Activation of Installation Space by the spect-actor. Pretoria, BODY / SPACE / EMERGENCE A Conference endorsed by the Laban/Bartenieff Institute of Movement Studies, New York. 17-19 January 2014. University of Pretoria, Drama Department. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

lewisj@tut.ac.za

Published: 4 May 2020

Author contributions

The authors had a discussion regarding intent for installations; drafted a few iterations of information and insights; presented it together initially at a conference in 2016; then Prof Lewis formalised the article from all preceding conversations and Q&A and interviews; again iterations on corrections of intent from Dr van der Merwe and his research on space and time.

1 Scenography refers to the art of representing objects in perspective, especially as applied in the design and painting of theatrical scenery.

2 There is a long-standing debate in the theatre academic fraternity regarding the difference (if any) between performing and acting where it is argued that performing encompasses all art forms in which a person conveys artistic expression through their face, body and/or voice. Acting commonly relies on facial gestures, body and voice to depict a character.

3 Theatre activist Augusto Boal coined the term spect-actor. As the name implies, a spect-actor is a figure who deliberately and self-consciously inhabits both worlds: fictitious and reality; as observer and actor in both.

4 Bitumen is a black sticky substance used as part of tar.