Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Koers

versión On-line ISSN 2304-8557

versión impresa ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.85 no.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.85.1.2467

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

HIV and me: The perception of children aged 10-12 living with HIV, and their expectations for adulthood

VIGS en ek: Die beskouinge van kinders in die ouderdoms-groep 10-12 wat met VIGS lewe, en hul verwagtinge vir volwassenheid

Hettie van der MerweI; Alva van der MerweII

IDepartment of Educational Leadership and Management, University of South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0736-4611

IILife Wilgers Hospital Lynnwood Ridge, Pretoria https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3403-567X

ABSTRACT

This article explores the understanding that children living with HIV have of their condition, ana the physical and psychosocial challenges they face in pursuit of their ideals for adulthood Analysis of the interview data, preceded by drawing-and-telling, confirmed literature findings on the importance of communication for complete disclosure and the need for repetitive discussions about HlV-related burdens to supplement medicine and treatment in pursuit of holistic well-being for children living with HIV Research findings revealed children's limited cognition of their HIV condition and their challenges with physical pain (attributable to their medicines and treatment) and psychosocial pain (stemming from family fragmentation and stigma). The children exhibited an intense desire for respect for their existence and for the realisation of their right to participate actively in communication regarding their HIV status Their ideals for adult life pertained to being of benefit to others. The findings contribute to the discourse on effecting holistic wellbeing for children living with HIV

Key words: complete disclosure, draw-and-tell technique, family fragmentation, living with HIV, physical challenges, psychosocial challenges, stigma

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel ondersoek die begrip wat kinders wat met VIGS lewe van hul toestand het, asook hul fisiese en psigososiale uitdagings in die nastreef van hul ideale vir volwassenheid. n Analise van die onderhouddata, voorafgegaan deur teken-en-vertel, bevestig literatuurbevindings oor die belangrikheid van kommunikasie vir volledige bekendmaking. Hierdie bekendmaking moet gevolg word deur herhaalde besprekings van VlGS-verwante struikelblokke om medikasie en behandeling te rugsteun in die strewe na holistiese welstand vir kinders wat met VlGS lewe. Navorsingsbevindinge het kinders se beperkte kennis van hul VIGS-toestand belig, asook hul uitdagings met fisiese pyn (vanweë medikasie en behandeling) en psigososiale pyn (vanweë gesinsfragmentasie en stigma). Kinders het n intense behoefte aan respek vir hul menswees, en aan die reg om aktief deel te neem aan kommunikasie oor hul VIGS-status. Hul ideale vir die volwasse lewe is daarop gemik om diensbaar te wees vir hul medemens. Die bevindinge dra by tot diskoers oor die holistiese welstand van kinders wat met VlGS lewe.

Kernbegrippe: fisiese uitdagings, gesinsfragmentasie, lewe met VIGS, psigososiale uitdagings, stigma, teken-en-vertel tegniek, volledige bekendmaking

1. INTRODUCTION

Africa is home to 60% of all humans living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and 75% of the global population of HIV-positive women, with South Africa being the epicentre of the disease: seven million people are infected, of whom 1.8 million are children (RSA, 2017). Although the influence of HIV on public health and the economy is constantly documented, the psychosocial influence on infected children requires more extensive reporting, for a better understanding of their situatedness. In this article, the focus is on the perceptions children aged 10-12 have of their condition of living with HIV and their ideals for adulthood.

The negative influence of HIV on public health and the economy, as studied and reported by the media, state authorities, the medical profession and academia, has been a topic of discussion since the emergence of the disease in the early 1980s. This coverage, which includes both epidemiology and epistemology, has improved the public's understanding of the transmission and signification of the disease, to the extent where HIV has become a chronic disease, rather than a terminal diagnosis. This changed scenario is evident in South Africa, where mother-to-child transmission declined from 3.5% in 2010 to 1.5% in 2016, and where 3.7 million people now receive antiretroviral treatment (ART) on a constant basis (PMTCT, 2019; RSA, 2017).

Despite these advances, patients and their families face significant psychosocial burdens when confronted with the disease, with children being adversely affected by practical and psychological consequences. Child-headed households are a reality, often grandparents take care of their orphaned grandchildren, and familial fragmentation occurs following the passing of caregivers, which leads to siblings being separated when the remaining family cannot care for more than one child (Cluver & Gardner, 2007). Affected children are vulnerable, as their sense of security is challenged by having to adapt to a new home with new rules while mourning the loss of their parents, and still having to deal with survivor's guilt and their own diagnosis (Maughan-Brown & Spaull, 2014). The burden orphaned children place on foster homes is significant. Many families bear the emotional and financial burden of an extra, non-biological child vying for attention and daily necessities, in addition to the responsibility of seeking treatment and visiting a clinic if the child is HIV infected. Families also deal with the reality of stigmatisation from the community as the death of each next adult confirms the disease's presence within a household (Campbell et al., 2010).

As regards children living with HIV, much research has been conducted on developing a critical consciousness and countering the stigmatisation associated with infection (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Campbell et al., 2010; Kawuma, et al., 2014; Plattner, 2013). Although the psychosocial influences of HIV on families have been well researched (Gachanja, 2015; Hosegood et al., 2007; Mabweazara, Ley, & Leach, 2018; Piko & Bak, 2006), only a limited number of studies have involved infected children directly in the research process. Our article contributes to the discourse on children living with HIV by understanding children's perceptions of their condition and their expectations for the future, through drawing and telling. Although the draw-and-tell technique is widely used to explore the influence of chronic diseases on children, the perceptions of children who are HIV-positive have not been studied sufficiently. Understanding children's cognition of their condition (as manifested in their daily circumstances and ideals for the future) through the draw-and-tell technique, can enable paediatricians and teachers to offer holistic support in treating and teaching children living with HIV.

Social capital theory underlying human conduct served as theoretical lens for our empirical investigation involving ten children aged 10-12, who were living with HIV and received ART, as facilitated by scheduled outpatient appointments at a paediatric HIV clinic in Bloemfontein, Free State province. The theoretical lens discussion is supplemented by comments on the need for children to be enlightened about their condition, and to voice their feelings and understandings through drawings. Our article concludes with a discussion of the research findings pertaining to children's understanding and acceptance of living with HIV, and their expectations for adulthood as engendered by their frames of reference. Our argument is that improved knowledge of children's perceptions of their HIV status and their expectations for adulthood can serve as guidelines for understanding and supporting those children in an empathetic and holistic way.

2. SOCIAL CAPITAL THEORY AND HUMAN CONDUCT

Human conduct is based on social capital which is acquired through the interactive functioning between the individual and society (Bourdieu, 1993). Societal functioning, which is accomplished through activities unfolding in multiple social spaces (e.g., education, medicine), is realised in social relationships. These relationships focus on constructive interaction between the individuals functioning in a particular space (e.g., children living with HIV, and the teachers and paediatricians who engage with them), to arrive at mutually acceptable performance. This performance relates to what Bourdieu (2005:43) calls "habitus", namely "permanent manners of being, seeing, acting and thinking" to represent "structures of perception, conception and action". These manners and structures serve a twofold function, namely to establish order (enabling individuals to orientate themselves in, and master, their world) and to enable communication (through a code of social exchange, whereby aspects of the individual and communal world are named and classified) (Moscovici, 1984).

Order and communication as habitus of a determinate group of human beings occupying a similar position in social space (such as children living with HIV) represent a practical systematicity, in the sense that all the elements of these individuals' behaviour have something in common (Bourdieu, 2005). This systematicity manifests as a set of acquired characteristics, which are the product of social conditions common to humans who are the product of similar social conditions (Bourdieu, 2005). In this article, these conditions represent the reality of children living with HIV, and the way in which they navigate the physical and psychosocial complications of their reality despite the uncertainties of their childhood. Living with HIV represents both "the generative principle of objectively classifiable judgements" and "the system of classification of these practices" (Bourdieu, 1994:405). The capacity to produce classifiable practices based on children's perception of their reality, to teach and treat children living with HIV holistically, and to distinguish between and appreciate these practices as constructive, is what represents habitus.

The reality of life with HIV can be considered to be an objective space, in which children express different points of view of this space, along with their will to transform this space (Bourdieu, 1994). This expression as habitus, which is internalised and converted into a disposition that generates meaningful practices and meaning-giving perceptions (Bourdieu, 1994), can manifest in an empathetic understanding which enables stakeholders to arrange holistic support for children living with HIV. In this regard, knowledgeable teachers and paediatricians can fulfil a directional role as social agents who organise social interactions that focus on providing holistic support according to empathetic systematicity. Holistic support for children living with HIV is realised through social capital resources (emotional, cognitive, spiritual, physical, financial and relationship-related) being made available to a greater or lesser extent to everyone present (Campbell, Williams, & Gilgen, 2002). Social capital resources, which are utilised through social interaction, inspire continued beneficial engagements, including an improved understanding of the reality facing children living with HIV, and offers holistic support for that reality.

3. DISCLOSURE TO CHILDREN LIVING WITH HIV

The desire and capacity of children to participate and be involved in decisions about their lives are increasingly acknowledged. The fact that they have sound insight into both biomedical and holistic notions of health - which they start obtaining from a young age - has prompted an acknowledgement of children's desire and right to full HIV disclosure, before any medical treatment or procedure is undertaken (Gibson et al., 2010; Piko & Bak, 2006).

Disclosure is usually prompted by children's questioning, problems related to adherence to a treatment regime, the need to maintain family trust, and cases of children's deteriorating health status. The withholding of status disclosure can be attributed to parents' desire to protect their children from psychosocial harm and is linked to their fear of negative reactions following disclosure (Vaz et al., 2010). However, the intentional withholding of information to protect a child from the burden of detail, can act as a stressor which hampers the child's capacity to interpret his/her symptoms and understand why s/he does not feel well (Gibson et al., 2010).

Shock and sadness - obvious emotions associated with disclosure - are dominated by feelings of relief when children can relate their suffering and multiple symptoms to a diagnosis (Ângström-Brännström & Norberg, 2014). A disclosure process involving one-way instruction which focuses on lifestyle and the taking of medication serves little purpose if children's health-related questions are not accommodated. By not providing complete information about their disease, and deflecting their questions with vague responses, adults discourage children from voicing their concerns, thereby heightening their vulnerability and leaving many questions unanswered. Complete disclosure is evident in open communication between healthcare providers and patients during consultations (Vaz et al., 2010).

Apart from providing complete information, Gachanja (2015) emphasises the importance of disclosure as an ongoing process which necessitates repeated discussions between the caregiver, healthcare provider and the child, while providing constant support and continued opportunity for debriefing and feedback. Considerate involvement in a child's condition enhances his/her experience of empowerment, whereas a lack of information inhibits self-worth and makes the child more concerned about the disease and its permanence (Rollins, 2005). Increasingly, children are being perceived as dignified human beings, whose opinions and reactions to major events in their lives must be respected.

As regards the general fears and stressors facing young patients who are admitted to hospital, they are especially scared when their disease - the very reason for their hospitalisation and treatment - is not explained to them (Angström-Brännström & Norberg, 2014). Children find painful procedures to be more tolerable when the information they receive from their lay parents are supplemented by professional information from medical practitioners (Livesley & Long, 2012). As primary caregivers, parents acknowledge that although they cannot completely fathom their children's experience with hospitalisation, young patients are visibly relieved when medical practitioners include them in discussions and decisions about their disease and treatment (Gibson et al., 2010). Considering the daily functioning of children living with a terminal or chronic disease (such as HIV), their struggle to cope with the disease and its implications sheds light on the importance of complete disclosure and the need for a holistic understanding of their circumstances.

4. HEALTH, MULTIPLE DEPRIVATION AND LIVING WITH HIV

The World Health Organisation (WHO, 1946) interprets health as broader than the mere absence of disease and infirmity, to include a condition of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing. Children confirm this holistic perception of health as relating to them feeling good and being active due to the lack of pain, and their happiness at being able to attend school and enjoy the company of friends (Piko & Bak, 2006; Vindrola-Padros, 2012). Although most children understand that the prevention of poor health can be linked to eating properly prepared food and maintaining personal hygiene, not being exposed to passive smoking and air pollution (Lowenthal, Cruz, & Yin, 2004), health as indicative of complete wellbeing is often hampered by conditions of multiple deprivation. Here, multiple deprivation pertains to any aspects that inhibit healthy living, including factors which are linked to socioeconomic disadvantage (e.g., severe poverty and the lack of an educationally stimulating environment) (Barnes et al., 2009).

The types of deprivation which inhibit physical development include having to survive on a life-limiting income, having poor/no accommodation, lacking enough food, and being exposed to a health-threatening environment. Illiteracy, a lack of morality, and limited knowledge and insight, as indicative of epistemological ownership, hamper an individual's psycho-cognitive development, which in turn negatively influences the management of health as complete wellbeing (Noble et al., 2007; Townsend, 1987). Within the South African context of multiple deficiency, Barnes et al. (2009) analysed the deprivation to which children are exposed according to five categories, with health and education-related indicators applying to each category. The category of material and income deprivation describes children who live in households with no refrigerator for the safe storage of food and medicine, and no radio or television to access information on healthy living. The category of deprivation due to unemployment includes children from households where no adults (aged 18 or over) are employed. Education deprivation pertains to households where children in the age group 7-15 are not in school or are in the wrong school grade for their age. A lack of running water and electricity, and crowded households where children share a sleeping space with several persons of different ages and genders, are indicators for the category of living environment deprivation. The category of adequate care deprivation relates to children growing up in households where both the mother and father are deceased, or where the mother and father do not live with their children in the same household (Barnes et al., 2009).

Being the children of deceased parents, older orphans are vulnerable to abuse and a lack of educational opportunities, as many are forced to leave school to find work and care for their younger siblings. The resentment of these children, at having to exchange the simplicity of childhood for caring for themselves and their younger siblings is exacerbated by fears regarding their own diagnosis, while mourning the loss of their parents (Cluver & Gardner, 2007). For many children in poverty-stricken environments, limited emotional stability (due to a lack of support from a mother or father figure) is intensified if they are physically unwell and feel ill due to having to take ART on an empty stomach (Kawuma et al., 2014). Grandparents who are left with orphaned grandchildren are confronted with parenthood as well as the physical limitations of old age - factors which are intensified by the demands of administering daily treatment and undertaking regular clinic visits with their HIV-positive grandchildren. The combination of the categories of deprivation results in children being exposed to conditions which challenge the odds of facilitating holistic wellbeing.

5. HIV AND STIGMATISATION

The elimination of mother-to-child transmission through immediate treatment being initiated for babies with HIV, has resulted in a growing population of young children surviving their vertically transmitted HIV infection. They now live with the chronic disease and its physical and psychosocial implications, of which coping with the stigma associated with HIV/Aids is a pertinent factor (Hosegood et al., 2007; Maughan-Brown & Spaull, 2014). Persistent perceptions of HIV as a 'monster' that is associated with death and presumed bad behaviour are formed in children from a young age. The stigma around HIV largely evolved from allegations of homosexuality and illicit intravenous drug use, to encompass misguided assumptions regarding immoral behaviour and affliction through witchcraft (Campbell et al., 2010). Despite improvements in education and the raising of public awareness, stigma continues to be a pertinent barrier to diagnosis, treatment initiation and adherence, while the fear of disclosure prevents many patients from accessing resources (Kawuma et al., 2014). The fear of persistent stigma is a prominent reason why caregivers withhold disclosure from infected children (Plattner, 2013). These children must therefore cope with their own misconceptions and that of others surrounding HIV, while battling the physical challenges associated with treatment.

The effective medical treatment of children living with HIV at specialised paediatric HIV centres, has resulted in a growing population of vertically transmitted HIV survivors. It is crucial to understand these children's situatedness, to ensure that emotional support and epistemological insights align with the medical treatment of HIV. For a collaborative understanding on the part of paediatricians and teachers of the psychosocial disposition of children living with HIV in conditions of multiple deprivation, it is crucial to determine such children's ideals for the future and their efficacy in coping with challenges. To achieve this requires effective communication. The method of drawing and telling is useful for understanding younger children's situatedness, while granting them an opportunity to communicate their insecurities. The technique engenders in children a relief at being able to express any discomforting feelings.

6. THE METHOD OF DRAWING AND TELLING

If a picture paints a thousand words, therapists' use of drawing as the universal language of childhood enables children to safely explore their wishes and negative impulses, without fear of real consequences. By allowing children full freedom to express themselves in their drawings, without guidance or prompting, they can relive past traumas and communicate future hopes by openly picturing their fantasies and fears (Theron et al., 2011). Valuable information is gained by interpreting children's emotions and thoughts through studying colour use, brush strokes and recurring themes. However, the risk remains of over- or misinterpretation, as picture making is influenced by the drawer's social and cultural background and his/her personal frame of reference (Horstman et al., 2008). In this regard, two children may draw similar pictures, yet each will enable a unique interpretation. Further, although children's drawings are potentially windows into their worlds, their drawings cannot reveal the entirety of their mental state on paper.

To counter constraints relating to subjective interpretation and the completeness of information, the draw-and-tell technique prompts children to draw pictures of a specific topic, followed by them telling about the details of their drawings. Although the action of drawing is focused on a topic, children have complete freedom of choice regarding the why and how of their artworks (Rubin, 2005). Discussing a drawing helps to elicit authentic interpretation and serves as an icebreaker for further questions aimed at obtaining a deeper understanding of a specific child's situatedness.

The value of drawing and telling represents freedom of expression in a way which is familiar to children, while granting them an opportunity to elaborate on their perceptions to validate their own work (Angell, Alexander, & Hunt, 2014). Drawing and telling as a child-centred approach for collecting data boosts children's confidence, allowing them to share their true emotions and perceptions about topics such as living with HIV. This enables adults (teachers, paediatricians) to gain an authentic understanding of each child's situatedness.

7. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

To understand children's perceptions of their condition of living with HIV and their ideals for the future, we proceeded from an interpretive paradigm using drawing and telling. As proposed by Henning, Van Rensburg and Smit (2004) and Denzin and Lincoln (2011), we selected the genre of a qualitative case study, to arrive at an in-depth understanding of the meaning the young participants derived from their situation, and of their expectations for the future. We conducted our investigation with ten HIV-positive children aged 10-12, who were receiving life-long Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Treatment (HAART) at a paediatric HIV centre in Bloemfontein, Free State, at the time of the study. The participants - to whom their HIV status had been disclosed - were five boys and five girls.

Ethical clearance from the relevant authorities ensured adherence to the overarching principles of academic integrity, honesty, and respect for everyone and every matter involved. Informed consent ensured that all participants and their caregivers were familiar with the aims of the research, what participating in the research would involve, and participants' right to withdraw from the study at any time. Prior to each telling (interview) that followed the drawing action, we obtained permission from each participant to record the interview, and participants were subsequently approached to confirm the accuracy of the transcribed data.

Being alert to the element of power relationships when adults deal with children, we adhered to prerequisites by creating a relaxed, non-threatening, quiet venue with the caregiver present (if so preferred by the participant) (Horstman et al., 2008). Based on compassion for the participants' condition of living with HIV and the quest to understand their situatedness, we were empathically focused on the participants' non-verbal communication - enough so to realise when a child was becoming uncomfortable and no longer wished to continue with the process. Each drawing-and-telling situation occurred privately and individually, with us reinforcing a participant's option to decline to participate further at any point. Throughout, we verified that the participants were comfortable and happy to continue. This aligns with the recommendations of Angell et al. (2014) about willing participation and that participants must feel empowered and involved as equals in the data-collection process.

8. RESEARCH FINDINGS

In drawing and talking about their pictures, each participant determined the pace at which the process unfolded. We asked the participants to think about what it was like for them to have HIV and having to come to the clinic, and to draw a picture about that. To this end, we made available a blank sheet of paper, and a wide selection of crayons and pencils. The participants did not receive any further prompts and were not interrupted. They indicated when they had finished their drawings. When it came to telling, we encouraged the participants to go into details about their drawing, and we praised them sincerely on their art and originality. The conversation about a child's drawing became the platform from which the interview was conducted, with the participant being asked what HIV is, what it feels like to visit the clinic and take treatment for HIV, and their hopes and dreams for their lives as adults.

Below, we discuss our findings, concurring with consulted literature, under the themes relating to family fragmentation, confused understanding about HIV as a condition, mixed feelings about clinic visits and the taking of medication, and participants' hopes for their lives. To ensure confidentiality of disclosure and authenticity of interpretation, the participants' drawings and verbatim commentary on their drawings (which constitute the findings of the study) are distinguished by the labels P1 to P10.

8.1 The struggles of a fragmented family

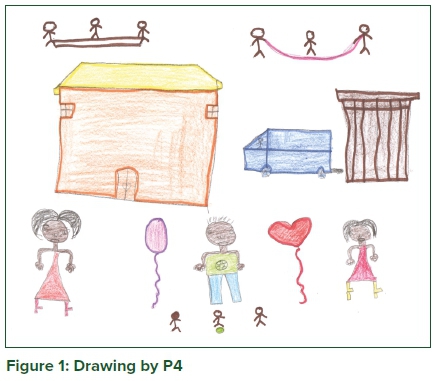

With reference to the category of adequate care deprivation (Barnes et al., 2009), none of the ten participants lived with both parents. As is typical of households which are prone to multiple deprivation, the father figure was absent in all cases. Six participants lived with their mother, two with their grandmother and two with a foster aunt. In all four cases where participants did not live with their mothers, the reason was that their mothers were deceased. Family fragmentation, as one of the debilitating effects of HIV, was clear from the drawing of P4, who had lived with her foster aunt since her mother died when she was eight years old.

Although P4's drawing depicts a normal and happy life, which includes a house, a car, outside ablution facilities and three kinds of play involving three children, the faces of the main characters are sad. These are the faces of P4, her foster aunt and her older brother returning her to her foster aunt in his car. It became clear from the interview with P4 that she was reminded of her mother and her own family when visiting her older brother and his wife. This caused her to become upset, after which being accused of having a bad attitude about having to return to her foster aunt and three cousins. Although no father ever featured in any portrayals of family life, and none of the children knew who their fathers were, P4 explained: "My aunt shouts at me when I tell my cousins that my father is not your [their] father." With the three cousins readily perceiving P4 as their elder sister, the complexity of a family life not comprising a mother and a father was exacerbated by the fragmentation caused by single parenthood, intensified by HIV-related maternal fatalities. With reference to Bourdieu (2005) on habitus and Moscovici (1984) on order in life, such fragmentation challenges both the foster child and foster family to a continuous reorientation of meaning-giving perceptions on the family as habitus within a world affected by HIV fatalities.

8.2 Confused understandings about the condition of HIV

Although each participant's HIV status was known to him/her, it was clear from the interviews that, except for P8, they did not have a basic understanding of their condition. P8 showed some understanding of the disease, explaining that "HIV is a disease that is not so bad, because when people drink tablets they get better". For P3, the reason for her regular visits to the clinic was merely "to get my injections", without any justification for this, or a valuation of the treatment. Some participants equated HIV with tuberculosis: as P5 explained, the result of acute coughing is to "spit into the bottle, the HIV is diagnosed from the spit in the bottle", with P1 concurring with this assumption, namely of receiving treatment "for my chest". HIV and tuberculosis often go hand in hand, resulting in the incorrect assumption that a person suffering from tuberculosis is necessarily also living with HIV. A disturbing answer came from P10, namely that "when you have HIV you are going to die". The countered explanation of treatment resulting in longevity engendered P10's changed perception, namely that "I am now happy to drink my medicine because it is going to cure me of HIV", which still does not represent an accurate understanding of the disease.

Adults' poor grasp of children's understanding of their disease was evident from interviews with the participants: regardless of the disclosure of their status, participants' understanding of HIV was confusing. With reference to Piko and Bak (2006) on children's desire for full disclosure, the participants' poor understanding of their condition could relate to disclosure representing a one-time event consisting of one-way instruction on how to live and take medication, without prompting any questioning on the part of the young patient. It could also relate to children's cognitive and/or verbal incapacity to express their views on a subject as foreboding as HIV, and adults' inability to adequately explain such a serious disease. Evident from the interviews was the participants' lack of proper understanding of their HIV status, and with reference to habitus as a structure of perception and conception (Bourdieu, 2005), the need for clear explanations and repeated discussions with children about their disease was deemed crucial.

8.3 Perceptions about clinic visits and the taking of medication

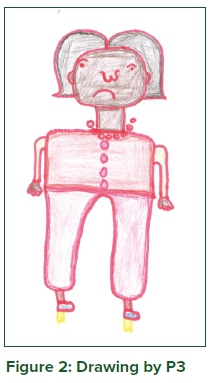

The participants' comments regarding their regular clinic visits varied from being positive, i.e., receiving medicine to keep them healthy (P5) and enjoy riding the lift at the clinic (P10), relishing the company of other children (P6), to being negative because of having to receive 'injections' (P9) and being bored there (P3). P3's boredom was evident from her self-portrait as an unsatisfied girl, which was related to the frustration of perpetuated inactivity while waiting to consult the doctor, which she wished could be countered by television viewing as distraction.

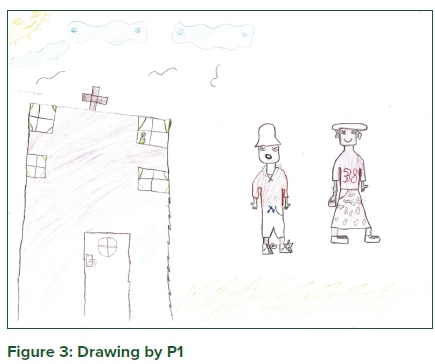

The persistence of stigmatisation for children living with HIV was confirmed by a comment from P1. In a drawing of him and his mother coming to the clinic for his regular treatment, P1 explained that his sad face was because "the people at the clinic are staring me down, they don't like me, I feel sad when they stare me down". P1's awareness of stigmatisation, engendered by prejudice in his surrounding environment, subconsciously influenced him to experience every situation as judgemental (including his visits to the clinic) as it persistently reinforces his HIV status. With such awareness of social stigma engendering stigma internalisation, children inculcate society's negative views of them and their illness. This has a destructive impact on their self-image and is a major contributor to the high rates of depression which are prevalent amongst HIV-infected children.

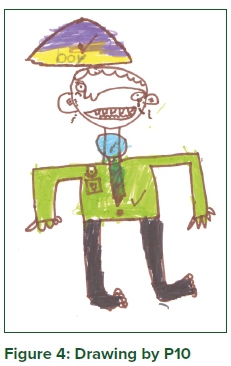

Related to the emotional struggle of coping with stigmatisation is the physical struggle of "feeling pain in my stomach" (P10) (a side-effect of ART medication, which is exacerbated by multiple deprivation in the sense of taking the medication on an empty stomach). Although P8 countered the discomfort associated with HIV treatment with the reassurance that "HIV is not so bad because when people drink tablets they get better", P10 confirmed that his crying face in his drawing is testimony to the fact that "HIVis painful", because of constantly having to live with stomach ache. In addition to stomach ache, participants complained about nausea, because "after taking the pills I want to vomit" (P1), which is exacerbated by "the bitter syrup" (P3) when the tablets are out of stock. All these experiences emphasised the challenge for children to maintain the 95% adherence level necessary for the virological control of the disease.

The act of children frequently spitting out their HIV medication, as generally reported by healthcare workers, bears testimony to the former's desperate pursuit of a comfortable physical condition which is free from pain, nausea and that bitter taste in the mouth. However, non-adherence is also motivated by psychosocial factors such as maintaining secrecy from their peers and, prompted by a desire for autonomy, a misguided attempt to take control of their own lives. With reference to family fragmentation and the fact that it is easier for children to disclose non-adherence to their own parents, they may opt to keep quiet for fear of being scolded or even suffering the abuse of a frustrated caregiver (Hosegood et al., 2007). Considering these facts, it is evident that children must have an opportunity to voice their frustrations and concerns, in order for these emotions to be considered in pursuit of a holistic support plan. The opportunity to reveal their feelings about HIV resulted in the participants eagerly sharing the discomforts associated with their treatment, as depicted by the crying face of P10.

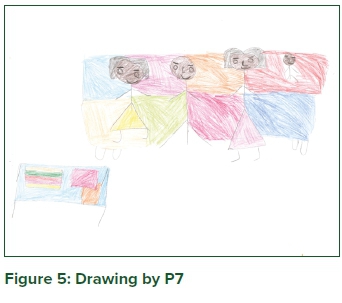

For P7, visits to the clinic were a positive experience, because of her engagement with medical staff. In her drawing, P7 focused on her interaction with healthcare workers who asked after her health, stating "I liked that the sisters asked me questions". P7 appreciated being spoken to directly, which conveyed a message of acknowledgement and respect for the dignity of her existence. While relaying her interaction with the medical staff, she seemed proud to have been able to answer all the healthcare workers' questions, with her pride relating to self-worth for being knowledgeable about matters regarding her condition. P7 confirmed that children deserve and want to be regarded as competent social actors who, according to Bourdieu (2005) and Moscovici (1984), can master their world and communicate this world through a code of social exchange.

With reference to Bourdieu (2005) on practical systematicity depicting similarity in individuals' behaviour, children living with HIV find ways to cope with the physical and emotional pain associated with treatment during their clinic visits. The presence of other children in the same social space reassures them of their common situatedness and the prospects of improved health - these serve as encouraging stimuli enabling them to face the challenges associated with medical treatment. Crucial to their will to transform their objective space (Bourdieu, 1994) is these children's appreciation for being personally engaged in treating their disease, and being viewed as human beings with inherent dignity, who are knowledgeable about their condition.

8.4 Ideals for adult life

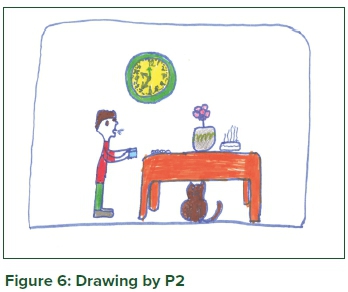

From participants' answers to the question what they wanted to be when they grow up, their frame of reference (as prompted by interactions with other people, objects and symbols in their immediate environment) became clear. Motivated by strong thoughts of morality and striving towards the greater good, the participants' aspirations were associated with their close contact with the medical environment at hospitals and clinics. In this regard, P2 wanted to become a doctor "to help people", with P7 opting to become a nurse "to help sick people" and P6 evaluating a career in medicine positively, because "it looks nice to help sick people". Participant aspiration was also linked to the need for policing crime-ridden environments, as P1 wanted to become "a policeman, to catch people that are evil"and P3 "a policewoman, to take care of criminals". Exposure to homes burning down in environments characterised by multiple deprivation (including a lack of electricity) prompted P10's ideal to become "a firefighter to help people when their house is on fire".

There was a pertinent sense of excitement and determination when the participants spoke without any hesitation about their anticipated occupations. This was reflected in P2's drawing of him returning from work and enjoying his meal at "seven o'clock in the evening" in a comfortable home with his cat for company. Asked whether he owns a cat, his answer was "No, but I love cats, I will buy a cat when I am a doctor". Considering Bourdieu's (1994) comments on living in an objective space with points of view of this objective space and constant interaction for the sake of betterment, it was clear that the participants aspired to become role models from a young age. It was also evident that these participants, who live with HIV, had an unyielding faith that their future would be as long and as certain as any other child's, regardless of the fears and uncertainties surrounding their disease.

9. CONCLUDING REMARKS

With reference to Bourdieu (1994) on systemising the classification of practices as they relate to the habitus of children living with HIV, the participants in this study exhibited an intense desire for their existence to be respected and their actions to benefit others. Given their ideals for the future, the participants wished to make a positive impact on the world. Keeping in mind the notion of establishing order to master their world (Moscovici, 1984), these children confirmed the physical and psychosocial challenges related to living with HIV and the lack of meaningful communication with adults for a better understanding of their situatedness. Linked to physical pain associated with treatment and the psychosocial pain of family fragmentation, the participants confirmed the debilitating effects of the persistent stigma associated with HIV. A crucial part of establishing order (Moscovici, 1984), was evident in these children's attempts to strive for self-worth and realise their right to actively participate in communication about their HIV status. Meaningful communication about children's HIV status is contingent on adults' cognition of children's understanding of their HIV situatedness.

Considering human expression of the will to transform dispositions within an objective space (Bourdieu, 2005), children's understanding of their HIV status represents a platform for meaningful discussions on the physical and psychosocial challenges pertaining to treatment, family fragmentation and stigma. Based on interaction between individuals functioning in the same objective space (Bourdieu, 1993), consistent age-appropriate means of communication can establish trusting relationships and channels of communication, allowing all stakeholders to form a holistic understanding of, and offer appropriate support for, children living with HIV. To this end, the draw-and-tell technique enhances adults' understanding of children's cognition of the virus living in their bodies and attacking their immune systems, which, due to its abstractness, eludes younger children's verbal ability to convey any cognitive perception of their situatedness.

Based on improved understandings of children's HIV disposition, directed by the will to generate meaningful practices and meaning-giving perceptions (Bourdieu, 1994), holistic support in dealing with physical and psychosocial burdens should include progressive communication at the clinic and school level. At school, interaction between infected peers - arranged by teachers through discussions in an environment where children can voice their feelings freely and openly - can contribute to a habitus which is focused on countering the physical and psychosocial challenges associated with HIV. In the clinic setting, discussing physical and psychosocial burdens as a routine part of consultations with paediatricians can enhance children's perception of their self-worth, motivating them to become active participants during consultations. The joint endeavours of teachers and paediatricians, to communicate HIV-related matters empathically while demonstrating respect for human dignity and a consideration for personal circumstances, steered by compassion for children's HIV situatedness and passion for their holistic well-being, can result in an improved habitus for HIV-positive children. Understanding younger children's situatedness for improved habitus can be arranged by using the draw-and-tell technique, to prompt them to participate in the free and open communication of their emotions and concerns. Further research should explore the specifics of a joint intervention programme (by paediatricians and teachers) to contribute in a holistic way to the wellbeing of children living with HIV.

LIST OF REFERENCES

Angell, C., Alexander, J. & Hunt, J.A. 2014. Draw, write and tell: A literature review and methodological development on the 'draw-and-write' research method. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 13(1):17-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X14538592 . [ Links ]

Ângström-Brännström, C. & Norberg, A. 2014. Children undergoing cancer treatment describe their experiences of comfort in interviews and drawings. Journal of Paediatric Oncology Nursing, 10:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454214521693. [ Links ]

Barnes, H., Noble, M., Wright, G. & Dawes, A. 2009. A geographical profile of child deprivation in South Africa. Child Indicators Research, 2(2):181-199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-008-9026-2. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. 1993. The field of cultural production: essays on art and literature. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P., 1994. Distinction: a social critique of the judgment of taste. In: D.B. Grusky, ed. Social stratification: class, race, and gender in sociological perspective. San Francisco: Westview Press, 404429. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. 2005. Habitus. In: J. Hillier and E. Rooksby, eds. Habitus: a sense of place. 2nd ed. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 43-49. [ Links ]

Campbell, C. & MacPhail, C. 2002. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: Participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science & Medicine, 55:331-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00289-1. [ Links ]

Campbell, C., Skovdal, M., Mupambireyi, Z. & Gregson, S. 2010. Exploring children's stigmatisation of Aids-affected children in Zimbabwe through drawings and stories. Social Science & Medicine, 71:975985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.028. [ Links ]

Campbell, C., Williams, B. & Gilgen, D. 2002. Is social capital a useful conceptual tool for exploring community-level influences on HIV infection? An exploratory case study from South Africa. Aids Care, 14(1):41-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120220097928. [ Links ]

Cluver, L. & Gardner, F. 2007. Risk and protective factors for psychological well-being of children orphaned by Aids in Cape Town: A qualitative study of children and caregivers' perspectives. Aids Care, 13(3):318-325. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120600986578. [ Links ]

Denzin, N.K. & Lincoln, Y.S. (Eds). 2011. The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Gachanja, G. 2015. The experiences of HIV-positive and HIV-negative children after receiving disclosure of their own and their parent's illnesses, respectively. PeerJPrePrints, 26 August. https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.1328v1. [ Links ]

Gibson, F., Aldiss, S., Horstman, M., Kumpunen, S. & Richardson, A. 2010. Children and young people's experiences of cancer care: A qualitative research study using participatory methods. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47:1397-1407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.03.019. [ Links ]

Henning, E., Van Rensburg, W. & Smit, B. 2004. Finding your way in qualitative research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Horstman, M., Aldiss, S., Richardson, A. & Gibson, F. 2008. Methodological issues when using the draw-and-write technique with children aged 6-12 years. Qualitative Health Research, 18(7):1001-1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732308318230. [ Links ]

Hosegood, V., Preston-Whyte, E., Busza, J., Moitse, S. & Timaeus, I.M. 2007. Revealing the full extent of households' experiences of HIV and Aids in rural South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 65:1249-1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.002. [ Links ]

Kawuma, R., Bernays, S., Siu, G., Rhodes, T. & Seeley, J. 2014. Children will always be children: Exploring perceptions and experiences of HIV-positive children who may not take their treatment and why they may not tell. African Journal of Aids Research, 13(2):189-195. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2014.927778. [ Links ]

Livesley, J. & Long, T. 2012. Children's experiences as hospital in-patients: Voice, competence and work. Messages for nursing from a critical ethnographic study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50:1292-1303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.12.005. [ Links ]

Lowenthal, E., Cruz, N. & Yin, D. 2004. Neurologic and psychiatric manifestations of pediatric HIV infection. Available online at http://www.bipai.org/Curriculums/HIV-Curriculum/Neurologic-ad-Psychiatric-Manifestations-of-Pediatric-HIV-Infection.aspx. (Accessed 1 March 2019). [ Links ]

Mabweazara, S.Z., Ley, C. & Leach, L.L. 2018. Physical activity, social support and socio-economic status amongst persons living with HIV and Aids: A review. African Journal of Aids Research, 17(2):203-212. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2018.1475400. [ Links ]

Maughan-Brown, B. & Spaull, N. 2014. HIV-related discrimination among grade 6 students in nine southern African countries. PLoS ONE, 9(8):1-11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102981. [ Links ]

Moscovici, S. 1984. The phenomenon of social representations. In R. Farr & S. Moscovici (Eds). Social representations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Noble, M.W.J., Wright, G.C., Magasela, W.K. & Ratcliffe, A. 2007. Developing a democratic definition of poverty in South Africa. Journal of Poverty, 11(4):117-141. https://doi.org/10.1300/H34v11n0406. [ Links ]

Piko, B.F. & Bak, J. 2006. Children's perceptions of health and illness: Images and lay concepts in preadolescence. Health Education Research, 21(5):643-653. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyl034. [ Links ]

Plattner, I.E. 2013. Children's conceptions of Aids, HIV and condoms: A study from Botswana. Aids Care: Psychosocial and Socio-medical aspects of Aids/HIV, 25(11):1418-1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.772278. [ Links ]

PMTCT. (Prevention of mother-to-child transmission). 2019. AVERT - Global information and education on HIV and Aids. Available online from https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-programming/prevention/prevention-mother-child (Accessed 4 June 2019). [ Links ]

RSA. (Republic of South Africa). 2017. Let our actions count: South Africa's National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs, 2017-2022. Pretoria: South African National Aids Council. [ Links ]

Rollins, J.A. 2005. 'Tell me about it': Drawing as a communication tool for children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 22(4):203-221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454205277103. [ Links ]

Rubin, J.A. 2005. Child art therapy: 25th anniversary edition. New Jersey: John Wiley. [ Links ]

Theron, L., Mitchell, C., Smith, A. & Stuart, J. (Eds.). 2011. Picturing research: Drawing as a visual methodology. Rotterdam: Sense. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-596-3. [ Links ]

Townsend, P. 1987. Deprivation. Journal of Social Policy, 16(2):125-146. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279400020341. [ Links ]

Vaz, M.E., Eng, E., Maman, S., Tshikandu, T. & Behets, F. 2010. Telling children they have HIV: Lessons learned from findings of a qualitative study in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(4):247-255. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2009.0217. [ Links ]

Vindrola-Padros, C. 2012. The everyday lives of children with cancer in Argentina: Going beyond the disease and treatment. Children & Society, 26:430-442. https://doi.org/10.1111/jM099-0860.2011.00369.x. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation (WHO). 1946. Constitution. Geneva: WHO. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

vdmerhm@unisa.ac.za

alva@kidzdoc.co.za

Published: 2 April 2020

The authors, being a teacher and a paediatrician respectively, embarked on this study jointly, with H. van der Merwe (the teacher) directing the literature study and A. van der Merwe (the paediatrician) the empirical investigation. The authors mutually share the pursuit of holistic support to children living with HIV.