Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Koers

On-line version ISSN 2304-8557

Print version ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.85 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/KOERS.85.1.2465

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

A practical explanation of ethics as a good corporate governance principle in South Africa and New Zealand - A case study

Cornelius (Neels) Kilian

North-West University. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2890-9350

ABSTRACT

This article uses two case law examples (New Zealand and South Africa), to illustrate how a questionnaire could be developed in practice as a method to identify a breach of ethics with reference to King IV, the FMA handbook and the NZX code. These two cases use terminology as found in relevant corporate governance codes and illustrate how to interpret those terminologies correctly, i.e. in terms of honesty and integrity. Relevant literature is reviewed in reference to the two case law examples. To interpret a corporate governance term properly, reference should also be made to appropriate legislation, e.g., the Companies Act when drafting a questionnaire. To understand corporate governance codes a holistic view should be adopted by the board of directors when drafting a corporate governance questionnaire. Such a questionnaire could provide the necessary insight as a method to prevent unethical business behaviour in future.

Keywords: corporate governance; integrity; honesty; director; ethics; King IV; NZX code; corporate culture

1. Introduction

In South Africa, corporate governance is regulated by the King Report, commonly referred to as King IV. This is applicable to both listed and unlisted companies in South Africa, and King IV replaced King III on the 1 November 2016. A listed company is defined as a company listed on the JSE Ltd, previously known as the Johannesburg Stock Exchange Ltd. In New Zealand listed companies are regulated by the NZX corporate governance code while unlisted companies could also follow the NZX corporate governance code voluntarily. In New Zealand a listed company is listed on the NZX, a common abbreviation for the New Zealand Exchange Ltd. In New Zealand corporate governance could also be regulated by the FMA handbook or Financial Markets handbook. In South Africa there are no such separate handbooks on corporate governance; the corporate governance text is simply referred to as King IV that is also relevant to close corporations as a business entity. In this article we will only be focusing on the first principle of corporate governance, namely ethics (King IV, the FMA handbook and the NZX code contain the same first principle, namely ethics) and on how it relates to relevant court judgments in both jurisdictions in terms of identifying a breach of ethics (Rossouw, 2002; Gully,2017).

2. Principles of ethics - South Africa

What is interesting about South Africa's corporate governance code is the definition section. King IV defines ethics as follows (King IV, 2016):

Considering what is good and right for the self and the other, and can be expressed in terms of the golden rule, namely, to treat others as you would like to be treated yourself. In the context of organizations, ethics refers to ethical values applied to decision-making conduct, and the relationship between the organization, its stakeholders and the broader society.

In addition, integrity is defined as follows:

In the context of governance and ethics, integrity is the quality of being honest and having strong moral principles. It encompasses consistency between stated moral and ethical standards and actual conduct.

Besides the above, King IV also defines "may" and "should", where the former is simply voluntary compliance while the latter denotes mandatory compliance with the essential code principles of King IV (King IV, 2016). Instead of code, King IV uses the term "policy" as a compliance standard document to establish whether the company is complying with King IV, or not. Part of the policy is intended to promote transparency, to grasp when a business decision has been honestly made and how it relates to integrity (Ackers, 2015). Policy and transparency are also defined in King IV; they play an important role in identifying honesty and or ethics in establishing good corporate governance principles in addition to King IV. The reporting on good corporate governance practices could be contained in financial statements, websites, social media, audit or any other ethics committee reports (generally only relevant to companies which are subjected to audited financial statements), compulsory financial sustainability reports and or any other material which could enhance transparency (King IV, 2016).

3. The "should" and "may" of ethics for listed and non-listed South African companies

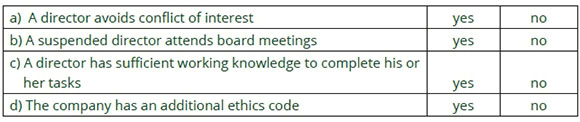

The principle of ethics stipulates when a company must follow an ethical code irrespective of its financial circumstances (Further, 2007). In this article we do not focus on the corporate governance requirements for close corporations as a business entity in South Africa. The corporate governance code relevant to close corporations is simply just a brief summary of the ethics principle; i.e. it lists principle 1 without any "should" or "may" (King IV, 2016). Besides the latter sentence, these "shoulds" for listed or non-listed companies are non-discretionary in their nature and must always be followed by the company or be implemented by the board of directors of that company (Nxumalo, 2016). For example, the directors of a company must abide by the following conduct characteristics which explain ethics in practice: directors must act in good faith and in the best interests of the company, they should avoid conflicts of interest and should act with ethics beyond mere legal compliance (Botha, 2009; King IV, 2016). In addition, the directors must act with care, skill and diligence and must always take reasonable steps to be informed of the facts relevant to management decisions (Padayachee, 2017). What is interesting is the fact that company directors must be well prepared to conduct company meetings, preferably to be well prepared before attending such a meeting (King IV, 2016). Besides the latter, all the principles relevant to ethics as explained in King IV could be contained in a simple checklist format; in South Africa it is not a requirement to draft a separate code or policy of ethics or that a company must monitor its own code of ethics by making use of a checklist. In total, King IV could be used and generally it provides for at least 53 checklist questions applicable to ethics only or to identifying breaches of ethical leadership and ethical citizenship (King IV, 2016). In other words, these 53 questions can be worded in such a manner to require only a yes or no to identify compliance with ethics without the company devising a separate code or policy. A no could indicate non-compliance with these 53 ethics principles and could be relevant to either listed or non-listed companies (Rossouw, 2002). An example of a checklist question could be:

It is also required that in the event of additional ethics policies/codes being drafted by a company, those policies are also circulated to the employees of the company as well as to other companies or organizations doing business with that company (King IV, 2016). The implication of the latter point is largely to stipulate the circulation of additional ethical codes as a method to promote future transparency in greater detail during the decision making process of that company (King IV, 2016; Van Niekerk & Olivier, 2012). Any breach of the additional codes (or King IV's "should" statements) could lead to disciplinary actions being taken by the company, i.e., disciplinary hearings based on the remedies/principles of the code available in the Companies Act 2008 relevant to directors who are in breach of their duties (Klopper, 2013). It is therefore possible that an additional code or policy of ethics could also be drafted by the company to such an extent that normal employees of the company (employees who are not directors) should also act in the best interests of the company and in good faith (King IV, 2016; Terraraz, 2008). The effect of the latter is also a fiduciary duty for employees, and any breach thereof could lead to a disciplinary hearing, which will be very unique from a South African perspective based on employee fiduciary duties (Du Plessis, 2010). Generally, King IV only regulates a fiduciary duty for directors and the consequences of a voluntary additional code for employees could require such duties of all employees at the same standard as that of a director because King IV is flexible in permitting the drafting of additional codes or policies (Botha, 2009). It is also therefore possible that close corporations may contain fiduciary duties for their members/ employees, although King IV does not require the latter as a "should" (King IV, 2016; Awad & Hegazy, 2016).

4. The relevance of King IV to Court Judgments in South Africa

As was observed earlier, King IV is not mandatory in its application; companies may make use of King IV voluntarily but if they do decide to make use of King IV then they must observe all the "shoulds" (King IV, 2016). In practice it is not always straightforward to grasp the duties of directors (care and skill or otherwise) or to comprehend honesty or the fiduciary duties of directors (Chepkemei, Biwott & Mwaura, 2012). In the following case, the court referred to King IV as a tool to identify a breach of director's duties, i.e. a non-disclosure of conflict of interest. In Mthimunye-Bakoro v Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (SOC) Ltd [2015] ZAWCHC 113; 2015 (6) SA 338 (WCC) the High Court of South Africa, Davis J, referred to the fiduciary duties of directors to act honestly and in the best interests of the company. Besides the latter, the court also gave a brief summary of the duties of care, skill and diligence, which are simply the actions expected of a reasonable director. The applicant in this matter was Mthimunye-Bakoro (chief financial officer) of the Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa who argued that she (as the chief financial officer) was not directly linked to any of this company's financial losses, totalling R15b (South African currency). The respondent argued that the applicant should take voluntary leave since her behaviour could prejudice further company investigations into her business decisions made previously on behalf of the respondent (Novick and Another v Comair Holdings Ltd and Others 1979 (2) SA 116 (W)). Also, her conduct during office hours might provoke an opinion amongst some or all employees that the respondent was not serious in suspending unethical directors for failure to comply with the relevant codes and standards of the company, i.e. in suspending an employee during investigations and or in re-employing the employee after conducting an investigation or disciplinary hearing. The applicant argued that she had to be at work and could not be suspended. The court simply held that under these circumstances there were serious breaches of corporate governance codes. The mere fact that the company had suffered financial losses of R15b was a clear indication that such a person should discontinue her duties as a director/employee immediately to prevent any further financial losses. The court held that to suspend the chief financial officer was part of the fiduciary duties of the board of directors since it would be in the best interests of the company to suspend this officer and await the outcome of her disciplinary hearing. On the other hand, a suspension could be contrary to good corporate governance principles (South African Broadcasting Corporation Limited v Mpofu and Another (2009) 4 All SA 169 (GSJ)). The court referred to the Mpofu case saying that part of their fiduciary duty is that all directors should be well informed of the facts to be discussed at board meetings and all directors should be present during any meeting to enable the board of directors to take proper decisions. To exclude a director, i.e. the chief financial officer, who allegedly committed a breach of fiduciary duties, is contrary to the Mpofu case's reasoning. It was argued by the chief financial officer's attorney that the applicant could not be excused from any board meetings after making a full disclosure, to the company, of her conflict of interest. To allow the chief financial officer to attend the duration of the meeting after full disclosure, is also part of the principle of integrity, and integrity should always be observed by a board of directors. In other words, the board of directors has a collective responsibility not to excuse a director for an alleged breach of fiduciary duty (after disclosure was made) so as to emphasise the integrity of their meetings or follow-up meetings. In addition, to take a decision without the presence of the chief financial officer could be interpreted as a breach of King IV and the Companies Act 2008. However, Davis J argued that in order to establish whether the integrity of a decision will be breached, it is important to focus on the relevant provisions of the Companies Act 2008 of South Africa (section 75(5)(d)) which require that a director should leave a board meeting immediately after disclosing any breach of fiduciary duties to the board. Therefore, to declare that such a decision to suspend her in her absence is contrary to King IV was disallowed by Davis J since her presence was not required at the meeting to vote in favour of her suspension or not. If the directors voted in favour of a suspension then it would be extremely difficult for the applicant to argue on the basis of the Mpofu case why her non-presence in following up board meetings would be in breach of integrity. This case illustrates the importance of King IV in establishing a breach of fiduciary duties and the relevance of the Companies Act 2008 in putting integrity into perspective i.e. to reject the reasoning of the Mpofu case. Therefore, King IV should always be interpreted with reference to the Companies Act 2008 in order to identify any unethical behaviour of the board of directors (Diplock, 2004).

5. Principles of ethics - New Zealand

5.1 Background

In New Zealand, two sets of corporate governance documents are available: the FMA handbook and the NZX code. In brief, the FMA corporate governance handbook's principle on ethics differs from ethics in the NZX code as explained in the paragraph below. The FMA handbook for companies who want to list on the NZX in the future states on page 5 that the principles mentioned in the handbook should be followed voluntarily by prospective listed companies. On page 5 the guidelines relevant to good corporate governance are discussed in a separate paragraph on the following page 6, which also contains commentary. The guidelines are merely used to explain a principle more clearly and or to guide the compliance officer or auditor or director to refer to the comments relevant to the given principle, for a better grasp of how to comply with the principle in practice, but such a principle could be very difficult to understand from a legal perspective (Legg & Jordan, 2014; Kabir, Su & Rahman, 2016). Guidelines could take the form of examples and the comments in this FMA handbook explain why it is important to report on a relevant guideline voluntarily (FMA, 2018). On page 7 it is clearly stated that companies are not required to report in detail the guidelines relevant to ethics but instead on how a company applied ethics in practice for reporting purposes. The principle relevant to ethics simply says in brief, that directors should set high standards of ethical behaviour when making business decisions (Arunachalam McLachlan, 2015). A practical example could also be that a director should at least know the industry in which the company operates, in order to make sound business decisions. The guidelines on page 8 of this FMA handbook simply explain what ethical decisions are, by requesting the board of directors to draft an additional code of ethics where honesty could be further explained. It is also possible that the additional draft code could define honesty or ethics since the FMA handbook contains no definitions. A component of the guidelines relevant to ethics is to include integrity and to emphasise that integrity is also important during the making or executing of business decisions (Kabir, Su & Rahman, 2016). The commentary on page 9 illustrates the importance of employing a compliance officer who will audit the ethics code or any supplementary codes on an annual basis as a method to continuously develop the company's ethics code (Lotzof, 2006; Kabir, Su & Rahman, 2016). Compliance could generally take the shape of a checklist which the company could draft and which in general contains yes or no answers to identify a breach of ethics; similar to the checklist example provided above for South Africa.

The question whether the FMA handbook is relevant to listed companies, was subject to a recent circular or discussion document namely "Review of Corporate Governance Reporting Requirements within NZX Main Board Listing Rules" in November 2015. This proposed that FMA guidelines or commentary should become part of the reporting mechanisms of a listed company in addition to a NZX code for listed companies (Gully, 2016). As a result a revised FMA handbook (in its present format it is more focused on unlisted companies) was released on the 28 February 2018 by the Financial Markets Authority or FMA. The new FMA handbook states clearly that it does not overlap with the existing NZX code and that the NZX remains the primary source for listed companies as regards good corporate governance reporting (Arunachalam & McLachlan, 2015). The NZX code for listed companies is similar in style to the FMA handbook owing to the fact that both issues contain guidelines and commentary, and these documents remain voluntary. The NZX code came into effect on 1 October 2017 and includes international best practices as well as some of the guidelines stated in the FMA handbook (Simpson, 2017). This code is not law, and listed or unlisted companies must indicate in their financial statements or on their websites if any breaches of ethics have occurred. It is also possible to state in the financial statements whether a company possesses a comprehensive code for corporate governance principles. Since the King IV has no technical history concerning the implementation or the relevance of other codes or documents pertaining to corporate governance in South Africa, we will compare the following principle of ethics relevant to the new FMA handbook and new NZX code. Even though the FMA handbook is not relevant to listed companies it nevertheless explains the relevance of additional corporate governance principles.

6. Principle of ethics in the NZX code

The NZX code remains a flexible document allowing listed companies to explain why a particular principle as explained by a recommendation is not relevant to a particular listed or unlisted company (Gully, 2017). The only requirement is that the company must explain why, in its opinion, the recommendation for a principle is irrelevant and listed or unlisted companies are free to determine suitable corporate governance practices for their businesses (NZX, 2017). Instead of disclosing corporate governance compliance in the financial statements of a company, a company may make use of its website to disclose compliance practices with respect to this code. In other words a recommendation is subject to compliance and or to an explanation why the company is unable to implement the recommendation, but the commentary in the code remains voluntary compliance disclosure in either the financial statements or on the website of companies (Arunachalam & McLachlan, 2015). Principle 1 states that there is a duty upon the board of directors to maintain high ethical standards and the board is liable to maintain this principle throughout the company; i.e. this is also relevant to employees (Arunachalam & McLachlan, 2015). The commentary requires a code of ethics to be drafted by the company, and these ethics should be universally applied to both directors and employees. The code should also be easy to read. Any breaches of the code of ethics could be voluntarily be disclosed by the company without stating whether any person (director or employee) should be subjected to internal disciplinary committees, etcetera. However, the reporting of a breach of ethics is mandatory, the management of breaches is mandatory, everyone should act honestly, everyone should take proper care of company business information, everyone should act in the best interests of the shareholder, stakeholder or otherwise, disclosure of gifts is mandatory, as are procedures relevant to whistle blowing and the like (NZX, 2017). The latter's mandatory disclosure examples of ethics would provide for transparency in the company dealings with other companies or when furnishing information or business information to other companies (Arunachalam & McLachlan, 2015). What is interesting about the code is that it does not stipulate definitions for particular words. Some of the words contained in the NZX code sound very simple; however they remain highly technical and only relevant case law should be consulted to comprehend, for example, honesty and the best interests of the company (Du Plessis, 2010; Lowry, 2012; Havenga, 2000). Generally the latter is part of the fiduciary duties of directors; in this code this duty seems to be relevant to employees as well and could be highly controversial when one focuses on relevant legal examples (Legg and Jordan, 2014). In other words, employees should exercise honest acts towards the company on a level similar to that of directors in order for these acts to be considered ethical (NZX, 2017). On the other hand, the court may also refer to legislation other than the Companies Act 1993 in New Zealand to identify honesty. Thus, the same case law could be relevant to directors and could also be applicable to employees to establish their breach of fiduciary duties when one observes recommendation 1.1 of the NZX code.

7. The relevance of the NZX code to court judgments in New Zealand

In the matter between NZX Ltd v Ralec Commodities Pty Ltd [2016] NZHC 2742, it is a complicated judgment, consisting of approximately 172 pages, dealing with the selling of grain on the New Zealand Exchange by making use of an independent company's trading platform (Clear Ltd) to record the transactions. It is impossible to give a precise scope of the relevant details of this case within a single article, since this case contains claims and counter-claims from both parties; the one side accused the other side of wrongdoing and vice versa. In brief, the relationship between the applicant and the respondent was identified as one of misrepresentations, incorrect information which was supplied relevant to projections made during a due diligence report by NZX (Hughes, 2012). These claims were made against Ralec, while Ralec in turn accused two NZX directors of deceptive conduct. For our purposes, we will only be focusing on the respondent's (Ralec) misrepresentations and incorrect information that are relevant to principle 1 of the NZX code. In this case the High Court of New Zealand did not make reference to any corporate governance code, i.e. the FMA handbook or the NZX code. The court relied on legislation only to identify any form of dishonest acts. As an example, the court made reference to section 6 of the Contractual Remedies Act of 1979 (CRA) of New Zealand which states the following:

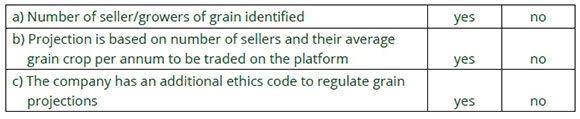

(1) If a party to a contract has been induced to enter into it by a misrepresentation, whether innocent or fraudulent, made to him by or on behalf of another party to that contract-

(a) He shall be entitled to damages from that other party in the same manner and to the same extent as if the representation were a term of the contract that has been broken;

The High Court focused on the term misrepresentation, and, in short, held that this term was not defined by CRA. In this regard, the due diligence report was based on future projections of the grain harvest and the question the court had to answer was whether such projections could be labelled as dishonest acts. Although the future is uncertain, the court held that a projection could be made honestly even though the end result could differ from the actual projection's result (Spiller, 2004). To know when such a projection is honestly made, it should be supported by a reasonable person's evidence, which is an objective test i.e. the number of grain growers, per ton per grower per annum etcetera (Deloitte, 2014). Although the NZX code does not define honesty, one can indicate an act of dishonesty by focusing purely on the trading platform's purpose - to connect an unknown number of grain growers to sellers via the electronic platform. Should a platform be used without knowing who the growers of grain are, this could be interpreted as risky business, as was held by the court, especially in relation to a reasonable projection of grain to be sold in the future. An example to identify an honest projection could entail the following checklist (Arunachalam & McLachlan, 2015):

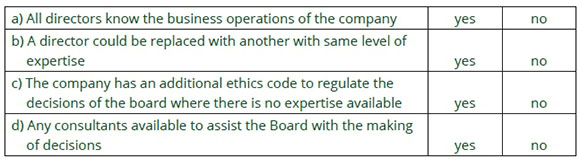

Therefore, to make suitable projections about the future production of grain or projected trade on the electronic trading platform, it is important to know how many growers/sellers will participate on this platform and besides the latter, whether they are all willing to give their permission to trade on that particular platform (Arunachalam & McLachlan, 2015). The court held that the projection of trade was indeed misrepresented without making reference to either the FMA handbook or the NZX code or whether the company in question had implemented a corporate governance code etcetera, to illustrate at least the willingness to disclose transparency in its projection calculations (Spiller, 2004). The problem with Clear Ltd was that only two directors and shareholders of Clear knew the business of trading grain on any electronic platform and were consequently dismissed on the basis of infighting. The respondent, Ralec, was aware of this circumstance yet never disclosed the dismissal of two key directors to NZX. The court could have analysed the above circumstances with reference to the financial statements/websites of Clear and Ralec as regards their voluntary compliance with corporate governance principles as a method to identify any relevant transparency in their dealings, i.e. Clear had no director who understood an electronic trading platform, to illustrate possible flaws in the integrity of the said platform. Although the NZX code was published in 2017, it is still relevant to our discussion since principle 1 in this instance was breached - clearly the board of directors could not act honestly and in the best interests of Clear if the two key individuals had been dismissed (H Timber Protection Ltd v Hickson International plc CA, 17 February 1995). Clear could also have used the following checklist to identify voluntary compliance with its ethics code or to establish ethical business behaviour - the same applies to Ralec:

The above checklist could immediately establish the presence of ethical behaviour and an auditor could, for example, declare in the financial statements that the board of directors lacked certain expertise to promote transparent business dealings etcetera (Pryce, 2012; Deloitte, 2014; Spiller, 2004). This would allow another company an opportunity to decide whether to continue with its business negotiations or not, as part of good corporate governance principles. Or in such an event Clear could make use of consultants who know the grain industry to comply with the requirements of an electronic platform relevant to buying and selling grain as a method to comply with any corporate governance code (Demidenko & McNutt, 2010). To keep doing business without the required consultants or two key individuals or non-disclosure of dismissed directors could be interpreted as making unethical business decisions (Kabir, Su & Rahman, 2016). The whole reason why principle 1 of the NZX code is important to corporate governance principles is to require responsible actions in the economic sphere and to build investor/stakeholder confidence by being transparent. It refers also to financial projections, that principle 1 in 1.1 requires integrity in "all actions" of the board of directors and their employees. "All actions" is a very wide phrase which merely denotes that a projection should be supported by actual evidence to promote the integrity of the projection (even if the future is uncertain), irrespective of whether a director or company employee had drafted the projection. Principle 1 of the FMA handbook does not require employees to act in the best interests of the company; therefore in terms of this handbook, a director should personally be responsible for drafting a projection of the selling of future grain. In the FMA handbook, principle 1 requires fair dealings with customers and it can be argued that no fair dealings could be possible if a company dismissed two key persons. To take decisions or business decisions without the input of these two key persons could be labelled as unethical decisions in terms of the FMA handbook. In this regard, the High Court did not refer to the principles associated with good corporate governance principles and also did not make any mention of any ethical or unethical business decisions based on the NZX code (or its predecessor) or the FMA handbook.

8. Conclusion

Although corporate governance principles are more complicated in New Zealand, it is possible to identify breach of corporate governance principles by making use of a simple checklist questionnaire. Such a checklist contains either a yes or a no and would allow a company to identify possible breaches of ethics before, during or after taking business decisions. A practical example could be a checklist based on the NZX Ltd v Ralec Commodities Pty Ltd [2016] NZHC 2742 case, which would have prevented litigation in the High Court of New Zealand if Ralec or Clear had devised appropriate ethics codes. Such a checklist would have immediately indicated that Clear had no knowledgeable directors pertaining to an electronic trading platform for grain, which is unethical business behaviour. It is also possible that Ralec could have disclosed the latter fact to NZX to promote transparency pertaining to the trading platform etcetera, as a method for the two entities to promote fair dealings with each other. It is also possible to create a checklist to identify future projections as being honest or dishonest. Such a checklist would not only promote the integrity of business projections but it would also be able to identify a possible breach of ethics, i.e. the unknown number of grain growers used in the projections. Legislation in New Zealand or court case references where legislation has been interpreted could also be used by companies to identify when an act is dishonest, i.e., part of misrepresentation of the relevant facts. The very same rationale was followed by the South African High Court in Mthimunye-Bakoro v Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (SOC) Ltd [2015] ZAWCHC 113; 2015 (6) SA 338 (WCC) to identify the integrity of board meetings. To prevent a financial officer from attending board meetings after her suspension is not contrary to good corporate governance principles. In fact, it promotes the integrity of such meetings since the financial officer who was responsible for severe company losses cannot participate in any future business decisions of the company. In addition, certain terms contained in any corporate governance code - integrity, honesty, fiduciary duties and the like - are extremely difficult words to understand in practice, but a checklist with a simple no or yes remains a good start in identifying a possible breach of ethics (Du Plessis, 2010; Lowry, 2012; Havenga, 2000).

References

Ackers, B. 2015. Ethical considerations of corporate social responsibility - a South African perspective. South African Journal for Business Management, 46: 11-21. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v46i1.79. [ Links ]

Arunachalam, M. & McLachlan, A. 2015. Accountability for business ethics in context of financial markets authority's corporate governance principles, New Zealand. Journal of Applied Business Research, 13: 19-34. [ Links ]

Awad, IO. & Hegazy, IR. 2016. Reviewing the implications of corporate governance, corporate social responsibility on corporate failure in the literature: Developing countries. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences, 7: 22-30. [ Links ]

Botha, H. 2009. Corporate governance, leadership and ethics. Management Today, 25: 55-57. [ Links ]

Chepkemei, A. Biwott,C. & Mwaura, J. 2012. The role of integrity and communication ethics in corporate governance: a study of selected companies in Uasin Gishu county, Kenya. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences, 3: 40-944. [ Links ]

Diplock, J. 2004. The Diplock-principles. New Zealand Management, 51: 4-5. [ Links ]

Du Plessis, J.J. 2010. A comparative analysis of directors' duty of care, skill and diligence in South Africa and Australia. Acta Jurídica, 263-289. [ Links ]

Deloitte. 2014. The Company Act, Australian 'Centro-Case' confirms duties of all directors. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/za/Documents/governance-risk-compliance/ZA CentroCaseConfirmsDirectorDuties 24032014.pdf. [ Links ]

Demidenko, E. & McNutt, P. 2010. The ethics of enterprise risk management as a key component of corporate governance. International Journal ofSocial Economics,_37: 802-815. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068291011070462. [ Links ]

Furter, E. 2007. Edifying morality: corporate governance. Enterprise Risk, 1: 32-35. [ Links ]

FMA. 2018. http://www.fma.govt.nz/assets/Reports/versions/10539/180228-Corporate-Governance-Handbook-2018.1.pdf. [ Links ]

Gully. 2016. https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/nzx-prod-c84t33un4/comfy/cms/files/files/000/002/269/original/Bell Gully- 29Feb 2016.pdf. [ Links ]

Gully. 2017. Bell Gully releases guide to the NZX corporate governance guide. https://www.bellgully.com/publications/bell-gully-releases-guide-to-the-nzx-corporate-governance-code. [ Links ]

H Timber Protection Ltd v Hickson International plc (unreported, Court of Appeal, Wellington, CA 113/94, 17 February 1995). [ Links ]

Havenga, M. 2000. The business judgment rule - should we follow the Australian example? South African Mercantile Law Journal, 25: 25-37. [ Links ]

Hughes, S. 2012. Finding the sweet spot: The future for kiwi future market regulation. Finance, 126: 44-45. [ Links ]

Kabir, H. Su, L. & Rahman, A. 2016. Audit failure of New Zealand finance companies: an exploratory investigation. Pacific Accounting Review, 28: 279-305. https://doi.org/10.1108/par-10-2015-0043. [ Links ]

King IV. (2016). https://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.iodsa.co.za/resource/resmgr/kingiv/King IV Report/ IoDSA King IV Report-WebVe.pdf. [ Links ]

Kloppers, H.J. 2013. Driving corporate social responsibility (CSR) through the companies Act: an overview of the role of the social and ethics committee. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal, 16: 165-199. https://doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2013/v16i1a2307. [ Links ]

Legg, M. & Jordan, D. 2014). The Australian business judgment rule after Asic v Rich: balancing director authority and accountability. Adelaide Law Review, 34: 403-426. [ Links ]

Lotzof, M. 2006. Compliance in Australia has continued to evolve over the last 20 years. Journal of Health Care Compliance, 8: 73-77. [ Links ]

Lowry, J. 2012. The irreducible core of the duty of care, skill, and diligence of company directors: Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Healy. Modern Law Review, 75: 249-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.2012.00898.x. [ Links ]

Mthimunye-Bakoro v Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation of South Africa (SOC) Ltd [2015] ZAWCHC 113; 2015 (6) SA 338 (WCC) [ Links ]

Novick and Another v Comair Holdings Ltd and Others 1979 (2) SA 116 (W). [ Links ]

Nxumalo, S. 2016. Prioritising good corporate governance: Investing. MoneyMarketing, 10. [ Links ]

NZX code. (2017). https://nzx-prod-c84t3un4.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/tudMMcsVc86yCu5kvAPgmPta?response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3D%22CorporateGovernanceCod 2017.pdf%22%3B%20filename%2A%3DUTF-8%27%27Corporate Governance Code 2017. pdf&response-content-type=application%2Fpdf&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&XCredential=AKIAIABUOTI7IOTRAXGA%2F20190305%2Fap-southeast-2%2Fs3%2Faws4 request&X-Amz-Date=20190305T084357Z&X-Amz-Expires=300&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Signatur e=d74fbc55eac1d8a09f1d9b5e9c6620fd1b842fb0ff1b4b30dd34df092677b6f7. [ Links ]

NZX Ltd v Ralec Commodities Pty Ltd [2016] NZHC 2742

Padayachee, V. 2017. King IV is here: corporate governance in SA revisited. South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy, 17-21. [ Links ]

Terraraz, M. 2008. Workplace ethics 101: Corporate governance. Enterprise Risk, 2: 36-37. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, T. & Olivier, B. 2012. Enhancing anti-corruption strategies in promoting good corporate governance and sound ethics in the South African public sector. Tydskrif vir Christelike Wetenskap, 48: 131-156. [ Links ]

Rossouw, G.J. 2002. Business ethics and corporate governance in the second King report: Farsighted or futile? Koers Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, 67: 405-419. https://doi.org/10.4102/koers.v67i4.380. [ Links ]

Simpson. 2017. New NZX corporate governance code - what listed companies need to know. https://simpsongrierson.com/articles/2017/new-nzx-corporate-governance-code-what-listed-companies-need-to-know. [ Links ]

South African Broadcasting Corporation Limited v Mpofu and Another (2009) 4 All SA 169 (GSJ). [ Links ]

Spiller, R. 2004. Investing in Governance. Chartered Accountants Journal, 83: 12-15. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Cornelius (Neels) Kilian

Private Bag X6001, Potchefstroom Campus

North-West University,

Potchefstroom, 2520, South Africa

corneliuskilian@gmail.com

Published: 20 Feb 2020