Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Koers

On-line version ISSN 2304-8557

Print version ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.85 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/KOERS.85.1.2466

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Power and Influence: Assessing the Conceptual Relationship

Mag en invloed: beoordeling van die konseptuele verhouding

Johan Zaaiman

North-West University

ABSTRACT

Power and influence are fundamental concepts used in the social sciences As closely-related concepts it is not easy to distinguish them clearly There are diverse definitions for power and influence in academic literature. Different views are also held on the relationship between these concepts. The present article revisits these debates. The researcher explains the difficulties to define concepts in general and those of power and influence in particular. This is done by referring to academic attempts to clarify the meaning of the mentioned concepts and thereby their conceptual relationship. It is demonstrated that the debate is complicated and a final answer cannot be found that easily. However, this article explores the differences in meaning between the concepts from the literature. Based on these distinctions, the researcher identifies the concepts' primary meanings as well as the areas where these meanings overlap. This article contributes by providing users of these concepts with conceptual markers that could help them use and integrate the concepts meaningfully.

Key concepts: Power, influence, definition, concept

OPSOMMING

Mag en invloed is kernkonsepte in die sosiale wetenskappe. As begrippe wat nou aan mekaar verwant is, is dit nie altyd maklik om hulle van mekaar te onderskei nie. In die literatuur bestaan daar uiteenlopende definisies vir mag en invloed. Daar bestaan ook verskillende beskouings

oor die verband tussen hierdie konsepte. Hierdie artikel herbesoek hierdie debatte. Die

navorser verduidelik die probleme om konsepte in die algemeen en veral van mag en invloed te definieer. Dit word gedoen deur te verwys na akademiese pogings om die betekenis van hierdie begrippe uit te klaar en daarby hul konseptuele verhouding te verduidelik. Daar word getoon dat die debat ingewikkeld is en dat n finale antwoord nie maklik gevind kan word nie Hierdie artikel ondersoek egter die verskille in betekenis tussen die konsepte uit die literatuur. Op grond van hierdie onderskeidings, identifiseer die navorser primêre betekenisse van die konsepte en dui die velde aan waar hierdie betekenisse oorvleuel. Hierdie artikel dra by om gebruikers van hierdie konsepte te voorsien van konseptuele bakens wat hulle kan help om die konsepte sinvol te gebruik en te integreer.

Kernkonsepte: mag, invloed, definisie, konsep

1. Introduction

Power and influence suffer similar defects as, for example, concepts such as equality and health. The meanings of the concepts seem clear when applied, however, scholars find it difficult to define the concepts of power and influence satisfactorily. This is a frustration and may cause doubts about its usefulness in scientific study. Nevertheless, these mentioned concepts remain fundamental building blocks in social and political analysis.

A further complication is that these concepts are related closely. In academic literature, the concepts are used interchangeably (Kotter, 1985; Ibarra & Andrews, 1993; Pfeffer, 1994); with overlapping meaning (Cassinelli, 1966; Porn, 1970; Wrong, 1979; Han, 2019); or with different meanings altogether (Mokken & Stokman, 1975; Lukes, 2005). Given the continuing stream of publications that apply these concepts in terms of different relationships, it may be useful to revisit their vaguely defined interrelationship. The objective of the present article is, therefore, to investigate the conceptual difficulties scholars encounter when distinguishing power and influence as concepts and aiming to draw relevant conclusions from the findings.

To various degrees, theorists have investigated the conceptual relationship between power and influence (Morriss, 2002; Zimmerling, 2005). Clearly the ongoing discourse on power is important. This is linked by the significant contours shown by the debate on this relational framework. Such a discourse makes it worthwhile to review the conceptual relationship between power and influence. The fluidity of the relationship makes it virtually impossible to reach a final answer in the debate. However, it can be conceptually helpful if the debate lines are drawn more vividly and visibly. Furthermore, clear conceptualisation can contribute to a more careful usage of the concepts in relation to each other. As a result, certain strains in the power debate may emerge more clearly. I.M. Copi (1978:126-130) argues that the purposes of definitions are to increase vocabulary, eliminate ambiguity, reduce vagueness, explain theoretically, and influence attitudes.

The present article thus firstly demonstrates that such outcomes are not attained that easily.

Based on the premise that power and influence are complex issues, the article commences with a discussion on the difficulties encountered when conceptualising such phenomena. Secondly, the article examines trajectories in the debate on the relationship between power and influence. The article concludes by explaining ways to consider in applying the concepts.

2. Complexity of defining power and influence

There are different reasons why it is difficult to define power and influence clearly. Firstly, in general the meaning of concepts is not fixed; secondly, both power and influence are, according to Gallie (1956), "essentially contested concepts"; and thirdly, the defining process as such presents shortcomings, which limit the conceptual power of definitions. These deficiencies are explained in the following paragraphs.

2.1 The meaning of the concepts

Defining power and influence is complex since the words as such do not intrinsically have a specific meaning. The meaning of a word refers to "those significant elements in all the many and various usages of the word which make the word comprehensible, to the area of agreement amongst users of the word" (Wilson, 1976:54). In the case of the present study, the elements or characteristics of phenomena to which words refer are complicated aspects of social life. Thus, evidently users of these words can only have a loosely held agreement about its meaning. This means firstly that the descriptive area of concepts is difficult to locate and map. Secondly, the borders of concepts' meaning can only be drawn indistinctly. Thirdly, usages cover different areas of the concept of which some may be nearer to a primary, essential or typical meaning than others (Wilson, 1976:29).

From the discussion above, it is clear that especially complex concepts cannot present clear-cut meanings. It is therefore unreasonable to expect that power and influence must have constant meanings, cover clear descriptive areas, have sharp borders and indicate clear, primary, essential or typical meanings. However, conceptualisation is a method to build agreement about the conceptions that may be linked to a certain phenomenon. Conceptual accord is an important aspect of scientific research and forms the basis for operationalising processes. Therefore, the attempt to clarify concepts must continue. In paradigmatic science this is per se a power game that instigates hefty debates about the scope and meanings of complex concepts.

Thus, regarding conceptualisation processes, it is crucial to interrogate motives and values underlying the specific usage of words (Copi, 1978:131-132). This raises relevant questions: Who uses concepts in specific ways; why in that way; and when in such a way? These questions are pertinent, especially for definitions that are connotative or intentional such as stipulative, lexical, precise, theoretical and persuasive forms of conceptualisation (Copi, 1978:136-142). Due to the limited scope of this article, these aforementioned questions will not be dealt with in depth.

2.2 Defining contested concepts

A second cause for the complexity to define power and influence clearly is that these essentially are contested concepts. According to Gallie (1956:193), such contested concepts "implies recognition of rival uses of it (such as oneself repudiates) as not only logically possible and humanly 'likely', but as of permanent potential critical value to one's own use or interpretation of the concept in question". Power has been identified as an essentially contested concept (Lukes, 1974; Haugaard & Ryan, 2012). Regarding the relationship of power and influence, this means that a commonly accepted agreement about the meaning of these concepts would be impossible. It stands to reason that there may be rival definitions or interpretations of these concepts. Nevertheless, in the power debate, attempts are still made to propose a specific definition for power (Forst, 2015). This article contributes to the mentioned debate by illustrating how the varied relationships between power and influence make it difficult to agree on a clear definition for either these concepts.

2.3 The defining process

Lastly, the process of presenting definitions as such has its imperfections. These deficiencies hamper the conceptual force of definitions - which also applies to conceptualising power and influence in this regard. Cohen (1980:134-140) explicates the object of concept formulation as (1) to communicate precisely; (2) have empirical import; and (3) be fertile in generating knowledge claims. He continues that firstly, nominal definitions, in which the definiendum is synonymous with the definiens, contribute to precise communication and can have empirical import. However, nominal definitions are not that fertile to generate knowledge claims due to the constrained meaning. The scholar secondly, contrasts nominal with connotative or intentional definitions, in which the definiendum is defined by specifying properties within the definiens. Such definitions do not facilitate precise communication, seeing that it is open to varying interpretations. But this openness makes connotative definitions extremely fertile for generating knowledge claims. Connotative definitions can obtain empirical meaning by being linked to observable conditions but usually do not. The third type is denotative or extensional definitions (which include ostensive definitions), in which the definiendum is defined through examples in the definiens. This type of definitions has direct empirical import and is useful to develop and evaluate ideas (Cohen, 1980:148150). However, such definitions do not support precise communication since it do not describe the properties underlying the examples.

The argument in this section is therefore that the idea of an ideal definition of power and influence is unattainable. The present article draws attention to the conceptual difficulties in distinguishing power and influence - because of these concepts' intricate nature but also due to the limitations of the defining process. To explain the relationship between power and influence in the literature, a distinction is made in the following sections between a lexical and a theoretical approach to the definitions.

3. Power and influence: a lexical approach

Morriss (2002) took a lexical approach in his analysis of the difference between power and influence as related to people. He attempts to delineate the meaning of the concepts and distinguish clearly between them on grounds of the different definitions presented in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). In this regard, it is worthwhile to remember Cohen's (1980) argument that this approach does not necessarily facilitate precise communication due to possible diverse interpretations of the definition. However, the definitions can still be fertile for generating knowledge claims.

Morriss (2002:9) points out that influence can function both as a verb and noun, whilst power is primarily a noun. He further emphasises that the etymology of power and influence differs. Originally power stems from "to be able" and influence from "being affected" (Morriss, 2002:9).

According to his lexical approach, power is the legitimate possession of capacity, or any capacity to produce effects, whereas both forms do not imply influence. For Morriss, influence is primarily a verb that affects or implies an act of influencing, which does not coincide with power. However power and influence overlap when both are defined as a capacity to influence or as a description of one who has the ability to influence others.

Morriss' (2002:9-10) comparison of the differences between influence and power is outlined in Table 1 below.

Table 1 above indicates that Morriss (2002:13) views power as referring to an "ability, capacity or dispositional property". This means that power does not denote the mere exercise as such or a resource. Power is primarily a capacity - for producing events and, therefore entails a potentiality. Power per se can thus not be observed; only its manifestations. These resultant events are described as exercises of power and not power as such. Power is the capacity for producing the mentioned events (Morriss, 2002:16-22).

In view of the exposition above, Morriss (2002) distinguishes influence from power. According to him, influence is affecting and power is effecting (Morriss, 2002:29-30). Influence interferes, causes a change, and impinges, whereas power brings about, or accomplishes outcomes. Influence has a more indirect working than the direct effects that power produces. For instance, influence makes certain choices more probable, whereas power determines what choices are available. A further important difference is that influence is habitual in its dispositional nature. This means that influence extends over time and therefore a deceased can still exert influence. In contrast, power has conditional dispositional properties. Power is intentional - entailing the ability for those in power to do what they want (Morriss, 2002:27).

Thus, Morriss (2002) supports a clear distinction between the concepts of power and influence. This conceptual differentiation helps provide clarity. However, as the following section shows, all theorists do not follow Morriss in this regard. Cohen (1980) notes that a lexical approach holds the possibility of varying interpretations. Therefore it is not surprising that theorists find other definitions more suitable for their designs. The lexical approach by Morriss also has the defect that it refrains from directly engaging the broader debate on power and politics. Furthermore Morriss (2002:38-42) absolves agents possessing power from normative scrutiny. He argues that normative questions about power only focus on the resultant actions in view of the capacity to bring about specific effects. The fact that people have a capacity to act is not a normative issue but the effects of their actions can be. According to Morriss (2002:21-22), if people are to be praised or blamed, this is based on assessing their actions or omissions, not their powers. However, such an argument is problematic. The question remains why certain people possess power - the capacity to act - and others do not. The unequal distribution of power should thus be queried.

Morriss' discussion of the difference between power and influence is indeed helpful in the discourse on the meaning of these concepts. His attempt to bring about conceptual clarity provides guidelines on ways these concepts can be applied more distinctly and mutually distinguishable. However, these concepts are seldom used in this way during theorising. Therefore it is important to explore other usages, which is done in the following section.

4. Power and influence: a theoretical approach

This section focuses on ways in which certain theorists handle the distinctive relationship between power and influence. This structure of this approach overlaps to an extent with the discussion of Zimmerling (2005) of the relationship between power and influence, where she plotted different theoretical relationships between these two concepts. In the following subsections, the various positions are highlighted that explain the different uses of and the relationship between the concepts of power and influence.

4.1 Power and influence as synonyms

Scholars often treat power and influence as synonyms. This approach eliminates the problem of having to clarify the difference and/or overlap between the concepts' meanings. A search for "power and influence" in academic search engines reveal, for 2019, over a hundred articles that use these terms interchangeably. An overview of the articles reveals that in this cross-usage, both concepts denote configurations or positions that shape behaviour, orders, decisions and policies in view of resources and access to opportunities.

Especially in management sciences, scholars employ the concepts of power and influence as synonyms (Kotter, 1985; Ibarra & Andrews, 1993; Pfeffer, 1994; Pettigrew & McNulty, 1995). This usage extends to other sciences as well. Dahl (1957) defines power as a special case of influence but in "Who governs? Democracy and Power in an American City" (Dahl, 1961) he applies these concepts more or less as synonyms.

Mokken and Stokman identify reasons why the meaning intersection between power and influence is so significant: "First, power can be a source of influence and influence a source of power. And second, processes occur whereby positions of influence are transformed into positions of power or, conversely, positions of power into positions of influence" (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:38). These reasons do not explain the meaning of the concepts, rather highlight its interconnection and indicate why scholars may give up the attempts at differentiation and use the concepts as synonyms. In contrast to this simplification of the relationship between the concepts, the following subsections examine alternative views.

4.2 Power as the more general, and influence the more specific concept

Power and influence can also be viewed as concepts that overlap but do not exactly have the same meaning. It has, for instance, been argued that power functions as the general concept, whereas influence is the specific one. Cassinelli (1966) views power as an ability "in which the effect of one person on another is potential" but which only actually takes place "in the relationships of influence and control" (Cassinelli, 1966:44).

Through influence and control, others' activities are affected. The difference is that with influence, agents do not require a special purpose or intention (Cassinelli, 1966:47). Regarding control, on the other hand, there is "a conscious effort to elicit a certain response" (Cassinelli, 1966:48). The distinct difference between the two concepts is that for influence, the subjects choose their responses; and for control they have no choice - "when an activity is influenced it is free and when it is controlled it is unfree" (Cassinelli, 1966:49). Table 2 below presents Cassinelli's view in this regard.

Similar to Cassinelli, Cartwright defines influence and power as follows: "When an agent, O, performs an act resulting in some change in another agent, P, we say that O influences P. If O has the capability of influencing P, we say that O has power over P" (Cartwright, 1969:125). In this sense, power and influence are defined in a broad sense. According to Cartwright, there may be power without influence but no influence without power. However, influence without power can be conceptualised and such broad definitions of both power and influence has limited usefulness (Zimmerling, 2005:109-110).

The problem with Cassinelli's and Cartwright's view of the relationship between power and influence is that they limit the usage of these concepts to interpersonal relationships. They do not accommodate the possibility that institutions and social processes may also be powerful and influential. Zimmerling (2005) also critiques the position of Cassinelli and Cartwright by pointing out that the exercise of power is defined as any triggered response. Such a definition will thus include "two pedestrians walking towards each other on the same side-walk from opposite directions swerve to avoid bumping into each other" (Zimmerling, 2005:109). Usually this general and customised interaction of people will not be viewed as power or influence since it is generally understood that these concepts have a more focused application.

Hunter (1953) and Porn (1970) also view power as the general term and influence as a subgroup of power. Porn draws a distinction between normative power (in which actions are punishable) and influence - functioning as power outside the normative realm (Zimmerling, 2005:133). However, Porn does not indicate clearly whether influence as both control and non-control can be considered power or merely influence as control (Zimmerling, 2005:134135). Porn's definitions are removed from the general usage of power and influence and are rather a distinction focusing on normative power. Nevertheless, such distinctions demonstrate the problem when definitions are constructed for theoretical purposes but not linked to the general usage of the term. Consequently, this further complicates a difficult debate. To collapse a concept such as influence into a definition of power does not help scholars understand the important differences between the concepts and the possible value of drawing a clear distinction.

4.3 Influence as the more general concept, and power more specifically

Contrary to the arguments above, other theorists postulate that influence is the more general concept and power the more specific one. Lasswell and Kaplan (1950) focus in the social sciences on political manipulation and argue in an elaborate and well-reasoned exposition that power entails a special case of influence. These scholars specify power as influence involving a threat of sanctions or deprivations for nonconformity (Lasswell & Kaplan, 1950:76). Power is unique in the sense that sanctions as threat are used as means. The problem in this regard, is that power is an exercise of influence, thus it remains a question whether power actually forms part of influence per se. Zimmerling (2005:126) explains in this regard: "The cause of confusion seems to have been 'only' that with respect to power the authors have given a definition concerning its exercise, whereas with respect to influence their definition concentrates on the potential involved in its possession."

The way Lasswell and Kaplan (1950:60) define the exercise of influence, its possession can already have an effect. The person with influence does not have to perform any action as such. However, in common usage it is difficult to reconcile the idea that doing nothing means exercising something. The limitation of power to cases where sanctions are involved is problematic. Power entails more than the exercise of sanctions. Lasswell and Kaplan, for instance, typify authority as a type of power albeit without coercion (Lasswell & Kaplan, 1950:128).

To view influence as the more general concept and power the more specific one, was the general approach in social psychology (Zimmerling, 2005:110-120). Typical of this usage was the definitions by French and Raven (Raven, 2008:1) published first in 1959. These scholars view social influence as "a change in the belief, attitude or behaviour of a person"; and social power as "... the potential for such influence ..." These broad definitions of the two concepts are not that helpful in clear social and political analysis. Furthermore, influence can occur without power. For example, Lukes (1986:16) points out that the economist Keynes exerted immense influence in Western countries during the 20th century but did not possess political power.

Wrong (1979) also distinguishes influence as the more general concept, and power as the specific one, linked to different effects. He explains: "Power is identical with intended and effective influence. It is one of two subcategories of influence, the other empirically larger subcategory consisting of acts of unintended influence" (Wrong, 1979:4) Table 3 below presents Zimmerling's (2005:129-130) interpretation of Wrong's distinction between these concepts.

Based on Table 3 above: In cell (a) power is exercised if A intentionally attempts to affect something in B (e.g. behaviour, attitude, preference, or desire), and succeeds in bringing about the desired reaction. Cell (b) is influence because A intentionally attempts to affect something in B but fails to bring about the desired reaction. In this case, power was not exercised but because A realised an unintended intervention, influence was exerted. In cell (c), A has no intention to affect B, however B reacted by doing something for A, which is a result of influence.

Adding to Table 3 above, Wrong (1979:4) emphasises that power relationships do not only have intentional but also unintentional outcomes. In power relationships, unintended influence can be a result beyond what was intended or envisaged at the outset. This makes the boundaries between power and influence less distinctive, which implies that power can also occur in cell b. However, Wrong is not clear on the extent to which this possibility changes his view on power. Zimmerling (2005:132-133) credits this distinction for providing a useful concept of power. The reason is that power is identified as a choice taken by the power holder and which opens the field for normative critique. Furthermore, Wrong's distinction follows the ordinary usage of the concepts of power and influence and precludes the subjects' awareness of the situation. However, Wrong's view is critiqued for its focus on intentionality as basis for the distinction between power and influence. Therefore, according to this view, intentional influence is also possible (Zimmerling, 2005:133).

4.4 Power and influence as complementary but mutually exclusive concepts

Zimmerling (2005) proposes different meaningful ways in which power and influence can function as complementary yet mutually exclusive concepts. One such approach is to base the distinction between the mentioned concepts on the view of sanctions. For instance, if sanctions are involved to change behaviour, attitude, opinion or belief, this amounts to power, otherwise it should be considered as influence (Zimmerling, 2005:136). Such a distinction is not actually used in scholarly work and it is not clear where authority fits into such a design. Another base for a distinction can be the view of persuasion. This means that if change stems from persuasion, the latter functions as influence, otherwise it must be considered as power. However, the concept of influence is also associated with veneration and deference, not necessarily persuasion (Zimmerling, 2005:137). The distinction based on persuasion, is therefore also not that useful as definition.

A further approach is to distinguish power and influence in view of the subject's interests or freedom. Lukes (2005:36) follows this route. His approach is presented in Figure 1 below.

According to Lukes (2005:30), "A exercises power over B when A affects B in a manner contrary to B's interests". Based on this premise, Lukes (2005:35) argues that power can overlap with influence if interests are involved but sanctions are not imposed. Lukes (2005:36) admits that in his treatment of the relationship between power and influence he does not resolve the issue whether rational persuasion can also be considered as power. A further critique of Lukes' view is that power does not only concern conflict of interests but can also be used constructively to advance subjects' interests or freedom. In this sense, his definition of power is flawed, which would also apply to his elegant distinction between power and influence outlined in Figure 1 above.

Mokken and Stokman (1975) distinguish power from influence by focusing on the subject. These scholars define both power and influence as abilities and attempt to bind these definitions to observable phenomena to make it suitable to empirical research (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:33, 37). Power is therefore defined as an ability to determine the elements of another's choice of options. More specifically: "Power is the capacity of actors (persons, groups or institutions) to fix or to change (completely or partly) a set of action alternatives or choice alternatives for other actors" (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:37).

On the flipside, influence entails "the possibility to determine the outcomes of the behaviour of others, without the restriction or expansion of their freedom of action" and therefore "Influence is the capacity of actors to determine (partly) the actions or choices of other actors within the set of action or choice alternatives available to those actors" (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:37). Zimmerling questions this definition by pointing out that influence is not necessarily wilful, seeing that the deceased can also exert influence (Zimmerling, 2005:141).

In addition, regarding political power, Mokken and Stokman (1975:49) attach particular importance to the availability of sanctions that determine the options open to actors and the instrument of non-decisions. In this sense, political influence becomes important as "the effective aggregation and organization of information, intelligence and expertise and the availability of good opportunities for access to levels of decision-making" (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:49). Influence can convert into power due to a critical advantage of information and/or advantage of access based on timing and representation (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:49-50). Power and influence can be evaluated in terms of two variables (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:51):

• value scope - set of values which is controlled from a given power position;

• system range - set of actors for which value alternatives can be determined.

Based on the scholars' definitions above, power can be a source of influence when people allow themselves to be influenced because of the position of power someone has over others. Mokken and Stokman (1975:38) refer to Carl Friedrich's "law of anticipated reactions" which states that if X's actions will be subject to review by Y, with Y capable of rewarding good actions and/or punishing bad ones, then X will likely anticipate and consider what it is that Y wants. On the other hand, influence can be a source of power when an actor with influence has a relationship with an actor who holds a position of power over other actors. An apt example is an expert councillor who gives advice behind the scenes to holders of power relying on his/her guidance (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:38). Influence can also be converted to power when an expert or a department provides a given set of alternatives that determine the final strategy on which decisions are made. Large organisations are also in a stronger position to advertise more effectively than smaller enterprises (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:39).

As was pointed out above, Mokken and Stokman aim to ensure empirical import in their definitions. However, they acknowledge the difficulty to measure empirically the potential or capacities, which lie in the core of the definitions. This means that an empirical investigation of power and influence should focus on observable as well as unobservable elements (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:40). Based on such a focus, these scholars caution against perceiving the use of force and action as indicators of power, seeing that in several cases these elements may rather be the resources of those who have less power. Major powers often do not require force or action (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:40). Therefore, it follows that "power behaviour and influence behaviour may be important as indicators, but they can derive their significance only in connection with potential or capacities" (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:40).

A distinction should thus be made between the application and exercise of power and influence and the actual behaviour brought about by power or due to influence. In relation to this view, Mokken and Stokman (1975:43-46) draw the significant inference that the elitist-pluralist debate stemming from the works of Dahl (1961) and Hunter (1953) actually had an individualistic bias - it is about individuals' actions. Thus, it can be concluded that the focus on decisions or non-decisions by setting the agenda in the elitist-pluralist debate, is more a matter of influence by individuals than stemming from power relations (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:46).

The mentioned scholars understood that power and influence primarily describe a relational framework. Actors within these relations possess power or exert influence depending on the capacity of their position or configuration they occupy in the relational complex. Within such a relational context, resources can support positions but also be used by positions (Mokken & Stokman, 1975:42). However, these scholars do not indicate clearly how this relational power and influence can be measured. The reason is that when they trace methods of power and influence, they have to resort to the actors' evaluation of these elements based on reputation, position, decisions and policies.

Zimmerling holds an interesting view on other scholars' distinction between power and influence. However, when proposing her own definitions, these also lack a proper explanation. In her definition, she adheres to the idea that these concepts are complementary but mutually exclusive. Zimmerling explains the difference as follows:

1. social power defines as the ability to get desired outcomes by making others do what one wants, i.e., by somehow (no matter how) imposing one's own preferences on them;

2. social influence, in contrast, defined as the 'ability' to affect others' beliefs, that is, their knowledgte (sic) or opinions either about what is or about what ought to be the case, about what is (empirically) true or false or what is (nor-matively) right or wrong, good or bad, desirable or undesirable (Zimmerling, 2005:141).

From the mentioned distinction, it is evident that Zimmerling is influenced strongly by the subject-oriented definition of Mokken and Stokman.

Parsons also distinguishes power from influence within the context of his grand systems theory (Parsons, 1963a; 1963b). He defines the concepts in terms of its contribution to maintaining the system. Within the hierarchy of control in the system he differentiates between several concepts of which power and influence are two that are related but independent. On this basis, Parsons posits an elegant definition:

Power then is the generalized capacity to secure the performance of binding obligations by units in a system of collective organization when the obligations are legitimized with reference to their bearing on collective goals and where in case of recalcitrance there is a presumption of enforcement by negative situational sanctions - whatever the actual agency of that enforcement (Parsons, 1963b:237).

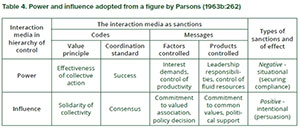

Despite this elaborate definition of power, Parsons does not clarify the concept of influence sufficiently. He refers to influence as "... a way of having an effect on the attitudes and opinions of others" (Parsons, 1963a:38), "positive sanctions" (Parsons, 1963a:44) and "... a means of persuasion" (Parsons, 1963a:48). However, Parsons draws the distinction between power and influence clearer in a figure, which is summarised in Table 4 below.

Table 4 above indicates that, for Parsons, power is exercised to ensure effective collective action by securing compliance. On the other hand, influence operates from a basis of solidarity, persuading others to render support. To elaborate on his systems model, Parsons distinguishes these concepts based on an analogy of money's function within the economy.

Although Parsons makes an interesting contribution with valuable argumentative points, these are forced and restricted by his specific theoretical framework. Such deficiencies thus limit the applicability of Parsons's distinction. Giddens (1991:257) criticises Parsons for not associating power with interest. Giddens queries how collective goals can be realised if the focus is not on interests. He points out further that Parsons' focus on normative consensus is flawed, seeing that, for Giddens, societies are characterised by the contestation of norms rather than by solidarity (Giddens, 1991:257).

5. Power and influence: what to consider in using the concepts

An objective of the present article was to draw relevant conclusions from examining the conceptual difficulties in distinguishing power from influence. This section thus examines, in view of the previous discussion, relevant aspects to consider when applying the concepts. First it must be emphasised that this evaluation does not aim to formulate an ideal or commonly acceptable definition of power and influence. In reality it is doubtful whether such a definition is attainable. A second point of departure is a common denominator, namely that both social power and influence focus on an "agent somehow affecting another's internal state of mind and/or external behaviour" (Zimmerling, 2005:101). This means that both power and influence entail a relationship between actors and other actors. In view of this overlap the question is therefore: What is the proprium of power and influence respectively, within such a conceptual relationship?

The discussion thus far about the conceptualisation of power and influence is summarised in Tables 5-7 below.

According to Table 5 above, summarised broadly: in essence power entails an ability or capacity to produce intentional effects by limiting alternatives for other actors. The interference in alternatives can take on different forms and be accomplished through sanctions and by altering the outcomes for other actors, or by impacting collective functioning.

On the flipside, the conceptualisation of influence is presented in Table 6 below.

In contrast to indications about power in Table 5 above, it is clear from the exposition in Table 6 that influence lacks direct intention. Thus, influence affects the probability of choices indirectly, thereby impacting other actors' behaviour, beliefs, knowledge, opinions, decisions, policies, values and norms. When comparing Tables 5 and 6, it is clear that conceptually, power and influence differ in primary meaning, operation and character but overlap to an extent in terms of process and outcome.

Regarding the dynamic relationship between power and influence, certain indications in Tables 5 and 6 can become blurred. For its operations, power as well as influence depend largely on resources and the availability of opportunities. In the struggle for resources and opportunities, power and influence can get entangled. When exercising power, influence can be used; but influence can also affect power. In both cases the one element in the relationship can be a source for the other.

As was pointed out, both power and influence focus on shaping the various dimensions (psycho-socio-political) of other actors and/or collectivities. Therefore, the actors' interests can characterise their roles in power and influence. The overlap of power and influence is clear since both impinge on the alternatives available to the other actors. Power entails an ability to limit choices for other actors, whereas influence affects the probability of choices by other actors. Table 7 below outlines the aspects of the overlap between the two mentioned concepts.

The applicability of the discussion above can be elucidated through examples as presented below.

Employee tasked: An employer may ask an employee to stay late and complete an important proposal. From the exposition above it is clear that this will be a case of power if the employee understands that the employer is limiting her/his alternatives - if the request is refused sanctions may be applied. On the other hand, this will be a case of influence if the employee understands this as merely a request without any threat of sanctions. In this regard, it would just be responding to a plea out of respect for the employer or firm. However, in several situations the employee can experience such a request as a mixture of both power and influence. In such a case, it can be argued not worth the trouble to distinguish the two concepts since both are concerned with affecting the alternatives available to the employee. This example demonstrates that a distinction between power and influence can be helpful to analyse the specifics of situations, however, the conceptual distinction has limitations.

Gang discipline: In the case where a gang member is disciplined in a violent way by the gang, the distinction between power and influence is clear. Evidently this is not a matter of influence, rather a direct intervention on the other actor. In this example the distinction and overlap between the concepts of power and violence open a different and interesting debate but disciplining will usually be viewed as an exercise of power.

Social media post: The final case is assessing a social uproar that may arise due to a controversial distributed social media clip. Such uproar can be viewed as influence since on the one hand, the actors want to reaffirm values and norms or may wish to challenge them. However, on the other hand, although the reactions may teem with threats, in most cases it cannot be realised. The actual ability to set alternatives or apply sanctions is absent. Nevertheless, the power of social media must not be underestimated. As an example, the #Me Too campaign applies, which had a major impact on social perspectives. Where people's attitudes and values are influenced powerfully, influence converts into power. This again demonstrates the complex dynamics between the two concepts and its application.

Currently there are manifestations of socially unacceptable social media in life streaming or through other content and "fake news". Due to these social-media outrages, companies operating such platforms are placed in an extremely powerful position to monitor, manipulate and sanction content. This is an excellent example of J.B. Murphy's point that the more power people can wield, the more influence they have, wanted or unwanted (Murphy, 2011:90). At present such companies are power agents who direct the influence of the social media. Thus, it not always easy to draw a clear-cut distinction between power and influence.

6. Concluding remarks

To conclude: the article demonstrated that the relationship between the concepts of power and influence was handled differently by diverse sources in the literature. A lexical approach can be very meaningful to help distinguish the concepts and identify their overlapping applications. However, the theoretical approach demonstrates several angles. Power and influence can be used as synonyms; power can be viewed as the more general concept and influence as the more specific one, or vice versa; and finally, power and influence can be used as complementary yet mutually exclusive concepts.

From the discussion above, it can be concluded that the essence of power is the ability or capacity to produce intentional effects by limiting alternatives for other actors, whereas influence lacks direct intention. Influence instead indirectly affects the probability of choices, thereby impacting other actors in their various dimensions from external conduct, inner life to policy practice and moral exercise/imperatives. Power and influence therefore differ in primary meaning, operation and character but overlap to a limited extent in process and outcome. In the struggle for resources and opportunities, power and influence may become entangled. Therefore, when exercising power, influence can be used but influence can also affect power within such a relationship.

The present article explored the differences in meaning between the concepts of power and influence. However, it was also illustrated that the two concepts are related closely. Thus, the complex relationship can lead to usages that link the concepts closely and overlap in meaning. Such overlapping is not necessarily a fault in the usage but also relates to the intersection of meaning between the concepts. Through this discussion the article gives clarity to users of the mentioned concepts. The focus is on those areas in which the concepts will be particularly appropriate to use and where scholars can take advantage of the interesting overlap in meanings and applications or unique connotations.

References

CARTWRIGHT, D. 1969. Influence, Leadership, Control. (In Bell, R., Edwards, D.V. & Wagner, R.H., eds. Political Power. A Reader in Theory and Research. New York, NY: Free Press. p. 123-165). [ Links ]

CASSINELLI, C.W. 1966. Free Activities and Interpersonal Relations. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. [ Links ]

COHEN, B.P. 1980. Developing Sociological Knowledge: Theory and Method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

COPI, I.M. 1978. Introduction to Logic. New York, NY: MacMillan. [ Links ]

DAHL, R.A. 1957. The Concept of Power. Behavioural Science, 2(3):202-215. [ Links ]

DAHL, R.A. 1961. Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City. New Haven, CT: Yale University. [ Links ]

FORST, R. 2015. Noumenal Power. The journal of Political Philosophy, 23(2):111-127. [ Links ]

GALLIE, W.B. 1956. Essentially Contested Concepts. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, London, 12 March 1956. [ Links ]

GIDDENS, A. 1991. The constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity Press.3 [ Links ]

HAN, B.-C. 2019. What is power? Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

HAUGAARD, M. & RYAN, K. 2012. Introduction. (In Haugaard, M. & Ryan, K., eds. Political Power: The Development of the Field. Opladen: Barbara Budrich. p. 9-19). [ Links ]

HUNTER, F. 1953. Community Power Structure: A Study of Decision Makers. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

IBARRA, H. & ANDREWS, S.B. 1993. Power, Social Influence, and Sense Making: Effects of Network Centrality and Proximityon Employee Perceptions. Administrative Science Quaterly, 38(2):277-303. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393414. [ Links ]

KOTTER, J.P. 1985. Power and Influence. New York, NY: The Free Press. [ Links ]

LASSWELL, H.D. & KAPLAN, A. 1950. Power and Society: A Framework for Political Inquiry. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

LUKES, S. 1974. Power: A Radical View. London: MacMillan. [ Links ]

LUKES, S. 1986. Introduction. (In Lukes, S., ed. Power. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 1-18). [ Links ]

LUKES, S. 2005. Power. A Radical View 2nd ed . New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

MOKKEN, R.J. & STOKMAN, F.N. 1975. Power and Influence as Political Phenomena. (In Barry, B., ed. Power and Political Theory. Some European Perspectives. London: John Wiley. p. 33-54). [ Links ]

MORRISS, P. 2002. Power: A philosophical analysis. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

MURPHY, J.B. 2011. Perspectives on power. Journal of Political Power, 4(1):87-103. [ Links ]

PARSONS, T. 1963a. On the Concept of Influence. Public Opinion Quarterly, 27:37-62. [ Links ]

PARSONS, T. 1963b. On the Concept of Political Power. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 107:232-262. [ Links ]

PETTIGREW, A. & MCNULTY, T. 1995. Power and Influence in and around the Boardroom. Human Relations, 48(8):845-873. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679504800802. [ Links ]

PFEFFER, J. 1994. Managing with Power: Politics and Influence in Organizations. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

PORN, Ϊ. 1970. The Logic of Power. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

RAVEN, B.H. 2008. The Bases of Power and the Power/Interaction Model of Interpersonal Influence. Analysis of Social Issues and Public Policy, 8(1):1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2008.00159.x. [ Links ]

WILSON, J. 1976. Thinking with Concepts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

WRONG, D.H. 1979. Power. Its Forms, Bases and Uses. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [ Links ]

ZAAIMAN, J. 2007. Power: Towards a third generation definition. Koers, 72(3):357-375. [ Links ]

ZIMMERLING, R. 2005. Influence and Power: Variations on a Messy Theme. Dordrecht: Springer. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Johan Zaaiman

johan.zaaiman@nwu.ac.za

Published: 20 Feb 2020