Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Koers

versión On-line ISSN 2304-8557

versión impresa ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.84 no.1 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.84.1.2449

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The Idea of a "For-Profit" Private Christian University in South Africa

Morné DiedericksI; Magdalena Catharina DiedericksII

IEducation, Academic and Reformatory Training Studies (AROS)

IINoordwes Universiteit

ABSTRACT

The one-sided focus of Christian higher education in South Africa on the field of theology ana the lack of integrating faith and learning in other subjects emphasizes the need for a Christian university in South Africa. The question addressed in this article is whether a Christian university can also be for-profit, considering the fact that all Christian private higher education institutions in South Africa are non-profit. There are numerous criticisms against for-profit higher education institutions. The greatest of these are that for-profit private higher education institutions miss the purpose of what it means to be a university and that profitable higher education institutions exploit students. The church also has numerous criticisms of the profit motive, but from the Bible it is clear that there are two lines of thought regarding profit. The one is that profit is dangerous and that it easily becomes an idol; the other is that people are called to be profitable. This article concludes that there is room for a for-profit Christian higher education institution in South Africa. This for-profit Christian higher education institution should be imagined in terms of its understanding of profit regarding its mission, students, faculty and governance

Key words: Christian higher education, Governance, Faculty, For-profit, Mission, Non-profit, Profit

1. Introduction

In his Confessions, Augustine refers to profit in a spiritual sense. Augustine describes his own education as something that served to his own loss and not to his profit.1 It raises the question, what is profit? And what is profitable education? In his article "Why Do You Think They're Called For-Profit Colleges?" Carey (2010) provides an overview of the controversy that has arisen about for-profit higher education institutions. The debate on education and profit mainly centres on the following question: "Who gets the profit?" From a Christian perspective, there have been numerous works in the last decades about Christian businesses and the motive of profit.

In his controversial book Higher Ed, Inc.: The rise of the for-profit university, Ruch (2003:3) writes: "Why do nearly all Non-Profit Companies (NPC) or traditional higher education colleges have difficulty balancing their budgets? What is it about the historic, lovely, leafy non-profit campuses that makes them so costly and leaves them continually strapped for money? ... I must confess that until a few years ago I thought that all proprietary institutions were the scum of the academic earth. I could not see how the profit motive could properly coexist with an educational mission. While I did not know exactly why I believed this, I was certain in my conviction that non-profit status was noble, and that to be for-profit meant to be in it for the money, which was corrupting and ignoble. I let myself believe that what we were doing was about education and not about money. When my institution created budget forecasts that included provision for excess revenue over expenditures, I did not recognize it as the profit motive."

Private higher education in South Africa is growing and many opportunities for developing Christian higher education have also evolved. The question within this investigation is whether there is a "market" for Christian higher education in South Africa. In South Africa, we see many business men and women who govern their businesses in a Christian manner with great zeal. If these business men and women wanted to develop a Christian university in South Africa, what would such a university look like? And in what manner would they conceptualize profit in education?

Up to now, not much research has been done on the status of private higher education in South Africa and even less about for-profit higher education. The reason for this is because private higher education in South Africa is still in its infancy regarding research. The purpose of this article is to create a framework for discussion regarding the possible establishment of a for-profit Christian higher education institution in South Africa. In this article we provide an overview of the development of Christian higher education in Africa and South Africa, some critique on non-profit and for-profit higher education institutions in general, a Biblical perspective on "profit" and lastly, we imagine some features of a for-profit Christian university.

2. The growth of Christian Higher Education in Africa

The first six hundred years of Western higher education (1200-1800) was faith-based. In the last two decades many former Christian universities have been secularized by government bodies. Despite major fluctuations in higher education, Christian higher education has continued to grow (Glanzer, 2017:23).2 "Christian higher education institutions prospers in countries that allow a large degree of privatization, as in Brazil, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, and the United States, while they are virtually non-existent in countries with very little by way of private universities, such as Austria, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom" (Glanzer, 2017:24).

The global growth of private higher education is described by Carpenter et al. (2014:12) as a big surprise. Although America has been accustomed to private higher education for decades, it is still a new idea in many parts of the world. Africa only had a small percentage of private higher education institutions before the 1990s. Most of the private higher education institutions were based in Christian seminaries. Today, however, the picture looks very different and in most African countries nearly 20% of higher education institutions are private. In Ghana, for example, there were only two private higher education institutions in 1999, but only a decade later there were eleven private universities and nineteen private polytechnic institutions. Ghana's private higher education accounts 28% of national tertiary enrolments (Carpenter et al., 2014:12-13).

Growth in Christian higher education in Africa has increased dramatically in recent years. Glanzer (2017:24) explains that Africa has become the continent with the highest growth in Christian higher education. "Africa has been a hot spot, with 58 new Christian colleges and universities (16 Catholic and 42 Protestant) founded between 1990 and today. The largest of these institutions, the Saint Augustine University of Tanzania, founded in 1998, already has over 12,500 students."

In spite of the growth of Christian higher education in Africa and also in private higher education in South Africa, there is still a decline in Christian higher education in South Africa. To understand why there is a decline in Christian higher education in South Africa and why private education has not really filled the "market" for Christian higher education, we are going to provide a general overview of Christian higher education in South Africa.

3. Christian Higher Education in South Africa

South Africa's 26 public universities are all members of Universities South Africa. They are distributed over all nine provinces of South Africa. Each province has at least one university, with Mpumalanga and the Northern Cape Province having just acquired their own institutions in 2014 and 2015. Provinces that house the three main metropolitan centres, namely KwaZulu-Natal, Gauteng and the Western Cape, are home to the largest number of universities.

By using the definition of what is considered a Christian university (in the introduction), it becomes clear that none of the 26 public universities are regarded as Christian universities. The last public university regarded as a Christian higher education institution was the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education (PU for CHE), which gave up its Christian identity in 2004 when its name was changed to the North-West University in a forced merger as part of the changing of the South African Education landscape. There is still an overwhelming majority of Christian lecturers at the university. Van der Walt (2013) describes the PU for CHE change from a Christian university to a secular university in his article "How not to internationalize - and perhaps secularize - Christian Higher Education".

The historically Christian universities in South Africa, such as North-West University and others, still have a large number of dedicated Christian academics who perform their Christian calling with great zeal within the particular space that is granted to them. These Christian academics also publish fruitfully in national and international academic journals with a Christian character.

According to Coletto (2010:9), a higher education institution is not Christian if its lecturers are Christian or if some religious modules are added to the "normal" list of modules. A Christian university needs to implement a Christian curriculum, promote Christian governance and help develop Christian scholars. According to Theron (2013:5), it will not be possible to establish a public Christian university in South Africa. Theron further states that "Christians should start private Christian institutions to assist students in building a bridge between their faith and their daily lives." Theron also warns that the establishment of private Christian institutions should not cause Christians to isolate themselves from the public sphere.

Given this overview of the state of Christian education in public higher education institutions, we are now going to look at the status of Christian private higher education in South Africa. According to the register of private higher education institutions last updated in October 2018, there are 131 registered private higher education institutions in South Africa.3

34 of the 131 institutions are non-profit companies (NPC) and 97 are for-profit (Pty Ltd). Of the 34 NPCs, 24 institutions perceive themselves as Christian by referring to themselves as Christian in some manner on their website. Not one of the 97 Pty Ltd. institutions regard themselves as Christian.

Of the almost one million enrolled students in South Africa, there are between 6000 and 7000 students at these 24 non-profit Christian higher education institutions. This means that at least 99.3% of all students in South Africa receive their higher education at secular institutions. In general, it is clear that South Africa's leadership is largely influenced by students graduating from the secular universities of South Africa. Theron (2013:2) asks how Christian higher education can contribute to the moral formation of young leaders in societies where corruption and immorality are endemic. From these statistics it is clear that there are still many opportunities for the development of Christian higher education within the South African higher education system.

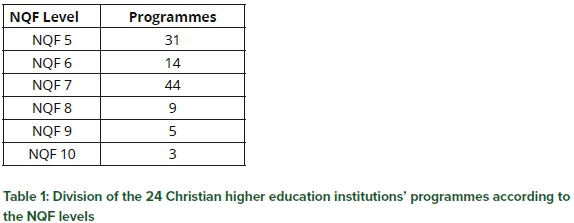

There are 106 different programmes between the 24 Christian institutions. The 106 programmes are divided into the NQF in the following manner:

It is noteworthy that only 16% of all Christian Higher Education programmes are postgraduate programmes. This state of affairs is worrying considering the fact that for Christian higher education institutions to grow and develop, they need to have qualified lecturers, which means that most lecturers at Christian higher education institutions would have completed their post-graduate studies at secular institutions.

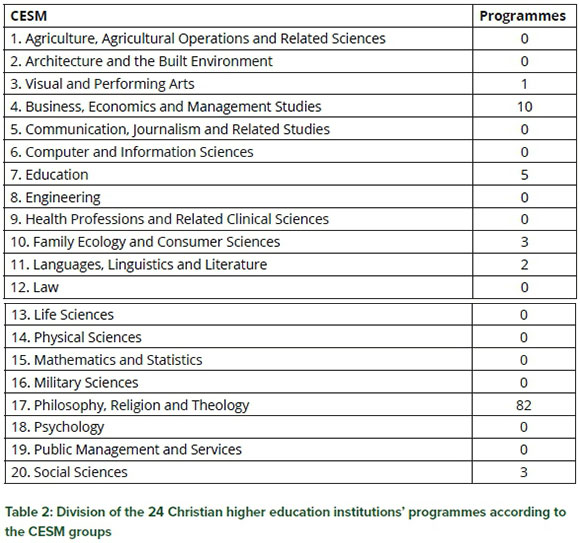

South Africa uses the Classification of Educational Subject Matter (CESM) to classify all the programmes in different disciplines. The 24 Christian higher education institutions' programmes are divided according to the CESM in the following manner:

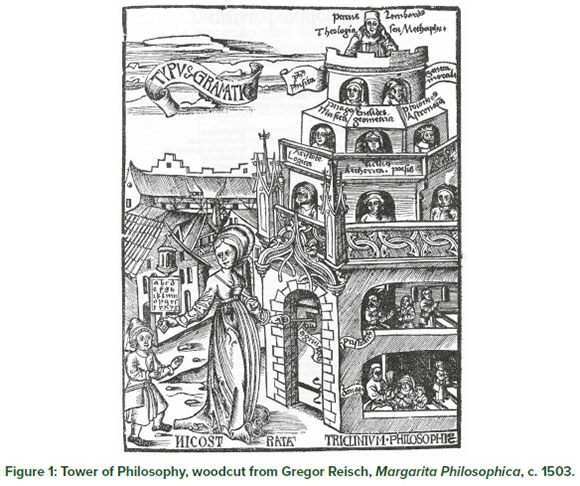

Most Christian NPCs are theological schools and 77.3% of all programmes offered by Christian higher education institutions in South Africa fall under the CESM group Philosophy, Religion and Theology. Glanzer's (2017:34) criticism is that Christian universities made the mistake of making theology the queen science. By elevating theology as the queen of all sciences, they isolate themselves in their own castle, far away from the "less important" disciplines, as depicted by the image Tower of Philosophy from the Margarita Philosophica (1503):

According to Glanzer et al. (2017:225), the role of theological teaching and the integration of theological education with other disciplines must be re-imagined and re-designed. Theron (2013:6) is of the opinion that South Africa currently has a greater need for Christian universities than more theological schools.

4. Governance issues in non-profit higher education institutions

A concern is that 62% of all private higher education institutions that were closed down in the past ten years were non-profit private higher education institutions. These statistics are even more worrying because non-profit private higher education institutions account for only 20% of the private higher education market. The problems encountered by these institutions are to comply with the requirements of the regulatory framework within which they should function. These problems are mainly related to the requirements of mode of delivery, facilities, the library and lecturers' qualifications.

The biggest critique levied against Christian- and non-profit higher education institutions comes down to a lack of funding. According to Glanzer's research (2017:24), only seven per cent of worldwide Christian higher education institutions receive state funding. Large percentages of Christian institutions also prefer not to receive state funds because they are afraid that state funds may have implications for their Christian character. Overall, Christian higher education institutions around the world are now overwhelmingly privately funded and will probably remain so in the near future. Sivaloganathan (2018) explains in his article "Why and how you should run your non-profit like a for-profit organization" that for-profit is a mind-set and approach that you will find in high-performing organizations of all shapes and sizes, including non-profits.

Poor management of non-profit companies is not new. Numerous books and articles have been written to identify and address mismanagement in NPCs.4 There is also plenty of literature criticizing the management of Christian and non-profit higher education institutions (Diedericks, 2016:107-108), where the biggest criticism comes from the circles of Christian academics themselves. Some of the criticism includes that some Christian higher education institutions hide behind their "Christian" name to disguise the poor quality of the education they offer. Poor quality Christian higher education institutions do not only impede the name of Christian higher education institutions, but also those of private education institutions. The regulatory bodies, especially in South Africa, are of great value in protecting the quality of private higher education institutions and it also increases the value of the accredited institutions.

5. Critique of "for-profit" higher education institutions

Over the last few years for-profit private higher education has expanded worldwide. This growth has occurred mainly in Europe, the USA, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, India, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Brazil, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, the Philippines and South Africa (Gupta, 2008; Shah & Nair, 2013:822). The largest for-profit university in the USA is the University of Phoenix, which already had 455,000 students in 2010. This for-profit model is being developed around the world. Laureate Education Inc., a for-profit company in America, already has 69 higher education institutions around the world with 740,000 enrolled students (Carpenter et al., 2014:12).

A mind shift has taken place over the last few decades where the university is increasingly seen as a business. Carpenter et al. (2014:11) describe it as an "industrial revolution" where higher education is being thought of as a product. The criticism of "for-profit" higher education is also abundant in the literature. The criticism includes among other things that profitable higher education institutions exploit students and that the grades or qualifications obtained by the students are of lower quality. In education institutions it has also become clear that the shareholders are not as interested in the identity of the institutions as they are in the profit the investment provides.

Heyns (2013) refers to the development of the for-profit university as the "economistic university". In the new economistic university, the planning of the university is structured around the budget and profit. Heyns (2013:8) explains that the reductionist view of the university as an "economistic university" has weakened our vision of the university. If a for-profit Christian university is understood as an "economistic university", then it cannot be regarded as a university, but needs to be seen as a Christian business. According to Heyns (2013:13), the economistic university changes our understanding of being human. It treats humans as commodities. "The commodification of universities according to the economistic vision intends to turn humans into instruments of profit and use. In other words, the aim is much more than merely to make a profit in order to make a university viable to conduct its academic functions. The economistic perspective sees universities as industries that should create wealth for its shareholders."

The consequences of the "economistic university" are that it excludes some important functions in society. Education is seen as a commodity within the university and if it does not lead to financial success, the education received by the student was not successful. Nussbaum (2010:1-2,7) calls this global marginalization a "silent crisis" which will weaken some important skills such as critical thinking, imagination and moral conduct.

Heyns (2013: 21) explains that the biggest problem with the for-profit university is their inability to be a true university. A university is an institution where human beings are formed to contribute to civilization by devising the complexity of the universe. If a for-profit university cannot do this, then it is not really a university. Collini (2012: 50) explains that the purpose of the economy was never a goal in itself, but it was a means of living wisely, agreeably, and well. According to Sandel (2012:5-6), markets and market values have come to govern our lives as never before, "... because no other mechanism for organizing the production and distribution of goods had proved as successful at generating affluence and prosperity". The logic to buy and sell today is not only applicable to material things alone, but it begins to rule our entire life.

In South Africa, for-profit private higher education institutions tend to focus solely on professional job opportunities. According to Carpenter et al. (2014:14), for-profit private higher education institutions are more likely to use information from other institutions than to create new knowledge. Furthermore, private for-profit higher education is more likely to be secular, culturally diverse and less politicized (Levy, 2007:17). Although these are generally seen as positive aspects in private higher education, they can also be negative in Christian higher education. Christian higher education strives towards an identity-driven institution that enhances a uniform vision and mission in the whole of the institution. Private for-profit higher education is inclined to choose the path of least resistance, with the aim of making their student corps as wide as possible, and they find it difficult to be identity-driven institutions.

For-profit private higher education institutions tend to be rather close-fisted. This financially driven mind-set causes them to make some decisions from a purely financial position. One of these decisions is the appointment of lecturers. For-profit private higher education institutions usually make use of part-time lecturers rather than full-time lecturers as the former need to be paid less. In Latin America, they call these lecturers "taxi cab lecturers", who are mostly involved in public universities, but make extra money by participating in for-profit private higher education institutions. As a result, the lecturer loses focus by being divided between too many tasks (Carpenter et al., 2014:15).

For-profit higher education is, based on the nature of its composition as a company, generally governed differently than public or non-profit institutions. Carpenter et al. (2014:16) describe it as "taking orders from the boss". The management structures of profit institutions tend to be more authoritarian. As a result, faculty and staff can not necessarily provide the management of the company with worthwhile input. Universities are also institutions that are built over hundreds of years. Profit institutions are not always aimed at long-term profit, but rather short-term profit. This short-term profit causes a lack of continuity within for-profit institutions because it may be transferred from one owner to the next within a short period of time.

Despite all the disadvantages of for-profit higher education, there are also many advantages. Private for-profit higher education is experienced as easily adaptable to change. This causes students to feel their courses are more job-related, which means that the rate of employability is higher. Private for-profit higher education is likely to move much closer to the future workplace of the student than traditional or public-funded institutions. These institutions also place particular emphasis on job-related training in their marketing (Shah & Nair, 2013:822, Carpenter et al., 2014:14). The negative aspect of this job-related approach is that for-profit institutions do not tend to develop programmes in fields such as social work, nursing or teacher education. "Likewise, the new for-profit privates tend not to make culture and share it with the community, through art galleries, orchestras, or drama programs" (Carpenter et al., 2014:14).

Private for-profit higher education institutions are also very competitive. The competitive outlook of businesses and private for-profit higher education causes institutions to be up to date with the latest innovative technology, they treat their students more like customers and they implement customer experience business principles to enhance the students' experience at the institution. This competitive attitude contributes to the fact that private higher education institutions, generally make their students feel important (Levy, 2007:16).

Galbraith (2003) shows that in many countries where the state has failed to deliver quality higher education, private higher education has filled the gap. In these countries private higher education enrolments comprise almost one third of tertiary students. Private institutions were better able to meet the higher education needs of these societies. According to Carey (2010:5), for-profits exist in large part to fix educational market failures left by traditional institutions, and they profit by serving students in aspects public and private non-profit institutions too often ignore.

6. Understanding "for-profit" from a Biblical perspective

There are few words which are more emotionally loaded than the word "profit". In Greek writings, one notes the emotional intonations when profits are mentioned. The Christian community is no less excited by the idea, for already the Apostle James suggests that the rich should "howl" because of the profits they have made from their employees.

There are two clear developments in Scripture concerning profit. The one is that profit for self-interest is not good and the other is an appeal to believers to be profitable (Mein, 2017:493). Firstly, the Bible condemns profit for self-interest. The dangers in the pursuit of money are clearly stated in 1 Timothy 6:9-10: "But they that will be rich fall into temptation and a snare, and into many foolish and hurtful lusts, which drown men in destruction and perdition. For the love of money is the root of all evil: which while some coveted after, they have erred from the faith, and pierced themselves through with many sorrows."

People whose only will is to get rich fall into different kinds of temptations. If someone is driven by the desire to get rich, they are also submissive to the will of the deity named Mammon. Towner (2006:405) describes the terrible things people do to themselves and others because they are lovers of money. Love for money is described as the root of all evil. Love for money ruins people's faith and trust in God, and without faith in God man is resigned to himself. The Bible makes it clear that the man of God must flee from the love of money.

In his letter to the Philippians, Paul refers to the other aspect of profit (Whittington, 2016:74). He thanks the congregation in Philippi for their financial support and then focuses on the "profit that increases to your account" (Philippians 4:17). This same focus is also clear in the guidance he offers to Timothy regarding the way in which he must teach "those who are rich in the present world" (1 Timothy 6:17). Rather than being "conceited or fixing their hope on the uncertainty of riches," Paul encourages Timothy to teach the people "to do good, to be rich in good works, to be generous, and ready to share" (1 Timothy 6: 17-18).

In Cafferky's discussion "What is the point of profit?" he says that profit is not the ultimate purpose of a business. When profit is emphasized by itself, it downplays the shared societal values that are at the root of why we enter into exchange relationships. "If the purpose of entering into exchanges was to merely gain a profit, the means by which these purposes are achieved would quickly turn to violence and destroy the ability of society to live its shared values" (Cafferky, 2015:393). According to Cafferky, profit is an indication of how the business meets the needs of others. Profit cannot be the only outcome. Profit should always be considered together with the needs of the community.

For-profit universities are not necessarily Christian universities. As mentioned earlier, there is not one for-profit Christian higher education institution in South Africa. Redekop (1982:32) says in his article "Understanding profits from the Christian perspective" when someone believes there is no problem with private property, they already have a concept of the advantages of profit. This also opens up a possible investigation into a for-profit Christian university. He describes the need for private ownership as an established need to have the ability to do something. Both the importance of individuality and its subjection to the larger whole are promoted in the Holy Scriptures. The essential reality of the individual person is recognized because the locus of responsibility is the individual conscience. Yet at the same time the collective nature of redemption, reconciliation, and ethics is taught. Thus, Christianity cannot be judged to support individualism unreservedly, nor can it be described as denying the reality of the individual.

Throughout the history of the church the church condemned profit for the sake of self-interest. Selfish promotion of self-interest is self-destructive. The accumulation of private property for its own sake was condemned in Jesus' teachings because it destroys the soul. However, profits and wealth are not considered inherently evil. It is rather the motivations and excesses behind wealth and profit that create the dangers. The conclusion must be reached that the Christian Gospel does not deny the reality and utility of profit, but strongly indicates its dangers for personal and social salvation. Lactantius states: "This is the greatest and truest fruit of riches: not to use wealth for one's personal pleasure, but for the welfare of many, not for one's own immediate enjoyment, but for justice, which alone perishes not" (Cadoux, 1925:603).

7. Imagining a "For-Profit" Christian University

All Christian universities should be profitable, be it a non-profit or a for-profit higher education institution. The for-profit must not, however, be focused on selfish self-interest but on the advancement of God's kingdom. In the New Testament church, each person is admonished to seek the welfare of their neighbour and to share with compassion. In fact, the Christian community is premised on communion and community. Having the same heavenly Father and a common Lord involves and implies a common life where mutuality is the norm.

Imagining and forming ideas forms an important part of any academic endeavour. Many articles and books regarding the reimagining of Christian higher education have recently appeared.5 It appears that Christian higher education has moved into a new phase of development over the last few years. This phase can be referred to as the phase where a higher education institution moves from a college to a university. We find this example at the Christian higher education institution Dordt College in the USA. Dordt College's name will change to Dordt University this year (2019). For this transition from college to university it became necessary for Christian academics to once again reimagine the university. What follows is an imaginative framework mainly developed from the work of Glanzer et al. (2017) in their book Restoring the soul of the university: Unifying Christian higher education in a fragmented age. This framework can be used in the discussion of a profitable Christian higher education institution regarding its mission, and its views on its students, faculty and governance.

7.1 Mission

The mission of a Christian higher education institution should pursue one unified Christian mission and not expire in the mire of a multiversity. The gain that it should yield is not selfish self-interest, but the working of the Holy Spirit that pours out the multiple riches of God's gifts in the students' lives through the gospel. The mission of a for-profit Christian higher education institution will play a major role in the way in which the institution will implement its understanding of profit. If the mission is aimed at promoting God's kingdom, then profit can be seen as belonging to the students and the community.

A Christian university's mission needs to be one of having a common identity. "Only with a common identity, narrative, and end can we find agreement about what it means to be a good friend, neighbour, citizen, and more" (Glanzer et al. 2017:292). According to Glanzer et al. (2017:262), a Christian mission must begin with the type of specificity that might be offensive to many contemporaries. The reason is that our understanding of what constitutes a successful education stems from our unique overarching narrative that includes what it means to be fully human. In his book The Idea of a Christian College, Holmes (1987) emphasizes that one of the core distinctions between a Christian higher education institution and a secular higher education institution is the institution's understanding of a human being: "Education has to do with the making of persons."

The Christian university's mission, according to Van der Walt (2010:112), should be examined from three angles: (1) its structure (its task), (2) its spiritual direction, (3) and its relevance within a particular context. In formulating a mission statement for a Christian university. The social positioning of the university should be considered regarding the above-mentioned three facets. An important feature that should form part of the mission of the Christian university is its understanding of the university's place in society. According to Van der Walt (2010:111), most Christian institutions show significant shortcomings, particularly their lack of a Christian philosophy of society. A university should not be an extension of a church or state, but it should have its own unique societal relationship. A university has ties with social spheres such as the state and the church, and then Van der Walt adds an important aspect, the economy. The university differs from these social spheres because it is an academic institution. Higher education institutions have their own unique stance that is supportive in its relationship with the church, state and economy, but they may not be politicized, prophesied or commercialized.

7.2 Students

The criticism against for-profit higher education institutions is that the shareholders make a great deal of money at the expense of the students. At a Christian university, the students should benefit from the profit. The students should also be able to share in the profit generated by previous generations, for example through bursaries or good facilities. Glanzer et al. (2017:272-295) uses the image of a greenhouse in his discussion of the Christian university's task to educate students. A greenhouse is a safe environment where plants are taken care of under the right circumstances so that they can flourish.

Likewise, the Christian university should also create a safe environment as a type of greenhouse for its students, an environment where students are protected from the dangers of the world and an environment where students can receive healing through the Word of God. However, creating a greenhouse environment for students is very expensive. And for investors who are only looking for quick profits, a greenhouse environment may look like a waste of money. However, in the effective development of a greenhouse for students, the true profit motivation of the institution emerges.

Carpenter et al. (2014:11) explain that the main focus of many for-profit universities is also to teach students to be profitable. The focus of the profit however isn't necessarily to do well to others but is focused on self-interest. According to Van der Walt (2010:126), the academic task of the Christian university should be the guidance and training of young inexperienced students who are trained as apprentices participating in the scientific process, with the aim of gaining basic perspectives as well as specialized knowledge. This policy regarding young people requires a lot of attention and time and does not always make sense on a balance sheet.

So easily within a for-profit university, the focus can shift to selfish interests in profit rather than the noble goal of truly developing students to be profitable in God's kingdom. However, it is this facet of student education that does not make sense on a balance sheet. This is a big issue which means nothing in the short term for the institution, but it could have an everlasting effect on a student's life. "Although a variety of psychological and sociological attempts have been made to begin the task of identifying the virtues or capacities of a flourishing (profitable) human being, Christians have the advantage of beginning with the soul of the matter. In other words, we can begin with a theologically informed understanding of our identity, story, and larger purpose" (Glanzer et al. 2017:281). To spend money on effective student development and student support is one of the contributing factors that distinguishes a university or higher education institution from a mere teaching centre. An investment in student lives through pastoral counselling, academic literacy, study groups, student life, prayer and so forth is the actual profit that any higher education institution should deal with.

7.3 Faculty

Students come and go, but faculties remain. The faculty is at the heart of any higher education institution. No wonder the quality of institutions is so easily measured by the quality of the faculty. The standards for excellence used to determine the quality of faculty carry a specific philosophy. This philosophy determines the criteria used for evaluating faculty. According to Glanzer et al. (2017:244), a Christian Higher Education Institution should have different criteria than secular institutions. The criteria should build interconnectedness between the duties of the lecturer. With an integrated approach he means an approach in which the three tasks of faculty, namely research, teaching and community service, are interconnected.

The Christian university should also help the lecturers not to lead a fragmented life. According to Glanzer et al. (2017: 252), one should not only try to balance the three tasks of research, teaching and community service, but they must be integrated. "One must have one's teaching, research, and service co-inhere." In setting up the faculty's duties, a Christian university should also take into consideration that a faculty member has multiple identities. A faculty member is also a parent, a husband or wife, a son or a daughter, a friend, a member of church and a child of God. The Christian university should not participate in furthering the fragmentation of faculty members' lives, but the university should contribute to the development of a whole person who seeks excellence in every aspect of their lives without idolatry.

The spirit of academic freedom is thriving in university life today (Rüegg, 2004:13-14). Academic freedom per se is of great value, but it is the fragmented 'silo effect' that causes the faculty to promote their own careers in the university on an individual basis. This form of individualism undermines the university's original intentions, where the university regards the professor as part of the community of scholars. According to Glanzer et al. (2017a:244), the academic freedom of the faculty should not undermine the single cause of the university. "We are a university; that is, we are all members of a body dedicated to a single cause. There must be among us distinctions of function, but there can be no division of purpose."

7.4 Governance

How do you opt out of competition? That is one of the biggest questions in a Christian institution. How do universities opt out of all the cultural assumptions that are made about successful institutions that translate into marketing campaigns and into students willing to come and spend their money for services? You can simply say "We do not care about them coming and their money," but that is incoherent because we have to, to make the institution work. So, it is really a paradox to know how to present yourself in a way that will still be understandable and attractive to people (Glanzer et al. 2017:304).

Universities today are primarily run by the administrators. And what are administrators interested in? They are interested in success of a particular kind. They want enrolment, they want revenue, and they want visibility. They are not asking themselves, What can we do to prepare our students for wisdom? That is not what they are thinking about. We could get at it this way: 80% of an administrator's time should be spent on enrolment, revenue and so forth; 20% of their time should be spent on the mission, emoting the mission and talking about it. And that is where such matters as wisdom and the like would always be front and centre (Glanzer et al. 2017:318).

According to Glanzer et al. (2017:299), to have the correct understanding of wisdom in a Christian university, one must have a correct understanding of time. A Christian university's concept of time should differ from that of a secular university. A Christian university has, like any other university, target dates to be achieved and an annual calendar with set dates and times, but when it comes to the development of knowledge and the gaining of wisdom, Glanzer distinguishes between "fast wisdom" and "slow wisdom". "As in our time, time is very short. We are now an anxious society in which everyone is greedy for unjust gain." Wisdom cannot, according to Glanzer et al. (2017:312), be quickly obtained. Leadership should, in the governance of the university, make room for faculty and students to come to wisdom in a slow manner. In order to maintain the balance between the growth of the institution as well as creating space for the development of wisdom requires wise Christian leadership.

To understand this balance between the growth of the institution and the development of wisdom, one should understand Christians as spiritual leaders. MacArthur deals with the concept of shepherds in Scripture and refers to the shepherds as spiritual leaders. Spiritual leaders serve as a buffer between the dangers of the world and the protection of the herd. Those in leadership in Christian universities are also shepherds who lead in the management of the Christian university. MacArthur (2017:226) names three motives for spiritual leadership which are also relevant for leadership in Christian universities, namely:

1. Spiritual leaders must not serve because of human constraints but because of divine commitments.

2. Spiritual leaders must not minister for unjust profit but with spiritual zeal.

3. Spiritual leaders must not lead as prideful dictators but as humble models.

8. Conclusion

From this article it is clear that Christian higher education in Africa is currently seeing huge growth, but there is a decline in Christian higher education in South Africa. The one-sided focus of Christian higher education in South Africa on the field of theology and not on a true integration of faith and learning in other subjects emphasizes the need for a Christian university in South Africa. A further question that is addressed in this article is whether a Christian university can also be for-profit. All Christian private higher education institutions in South Africa are non-profit private higher education institutions. The problem is, however, that non-profit private higher education institutions are statistically generally governed more poorly than for-profit higher education institutions.

There are also numerous criticisms against for-profit higher education institutions. The greatest of these are that for-profit private higher education institutions miss the purpose of a being a university, that profitable higher education institutions exploit students and that the qualifications obtained by the students are of lower quality. In education it has also become clear that the shareholders are not interested in the identity of the institutions but are more interested in the profits that the investment provides. "The university has usually been thought of as maybe a little odd or maybe as an ivory tower, but it's doing important things. The university now, rather than being viewed as something for the social good is either viewed as for consumer or private benefit, or it is viewed as itself almost a consumer of public good in ways that are not necessarily responsible or defensible" (Glanzer, 2017:301).

The church' also has a number of criticisms against the profit motive, but from the Bible it is clear that there are two lines of thought regarding profit. The one is that profit is dangerous and that it easily becomes an idol; the other thought is that people are called to be profitable. The conclusion of this article is that there is room for a for-profit Christian higher education institution in South Africa. However, the for-profit Christian higher education institution should be imagined in terms of the use of profit in terms of the Christian university's understanding of its mission, students, faculty and governance. In the words of Holmes (1987:11): "But by and large we have not dreamed big enough dreams."

References

Augustine St. 1976. The Confessions of St. Augustine. trans. Pine-Coffin, R.S. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Berman, D. 2014. Productivity in public and non-profit organizations. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bryson, J.M. 2018. Strategic planning for public and non-profit organizations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Cadoux, C.J. 1925. The early church and the world. Edinburgh: T.T. Clark. [ Links ]

Cafferky, M.E. 2015. Business ethics in biblical perspective: A comprehensive introduction. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

Carey, K. 2010. Why do you think they're called for-profit colleges. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 56(42), 88. [ Links ]

Carpenter, J., Glanzer, P.L. & Lantinga, N.S. eds. 2014. Christian higher education: A global reconnaissance. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. [ Links ]

Classification of Educational Subject Matter (CESM) http://www.che.ac.za/sites/default/files/publications/CESM August2008.pdf. (Date of access: 25 November 2018). [ Links ]

Coletto, R. 2010. Reformational institutions for higher education: opinions and information. Word and Action= Woord en Daad, 50(413), 9-14. [ Links ]

Collini, S. 2012. What are universities for? London: Penguin UK. [ Links ]

Diedericks, M. 2016. Guidelines for the development of religious tolerance praxis in mono-religious education institutions (Doctoral dissertation). [ Links ]

Freeborough, R. & Patterson, K. 2016. Exploring the effect of transformational leadership on non-profit leader engagement. Servant Leadership: Theory & Practice, 2(1), 4. [ Links ]

Glanzer, P.L. 2017. Growing on the margins: Global Christian higher education. International Higher Education, (88), pp.23-25. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2017.88.9691 [ Links ]

Glanzer, P.L., Alleman, N.F. & Ream, T.C. 2017. Restoring the soul of the university: Unifying Christian higher education in a fragmented age. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

Gupta, A. 2008. International trends and private higher education in India. International Journal of Educational Management, 22(6), 565-594. [ Links ]

Heyns, M. 2013. The economistic university: a brave new paradigm? Phronimon, 14(2), 1-24. [ Links ]

Holmes, A.F. 1987. The idea of a Christian college. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. [ Links ]

Hulme, E.E., Groom Jr, D.E. & Heltzel, J.M. 2016. Reimagining Christian higher education. Christian Higher Education, 15(1-2), 95-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2016.1107348. [ Links ]

Levy, D.C. 2007. Private-public interfaces in higher education development: Two sectors in sync. In World Bank Regional Seminar on Development Economics (pp. 16-17). [ Links ]

MacArthur, J.F. 2017. Pastoral ministry: How to shepherd biblically. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. [ Links ]

Mein, A. 2007. Profitable and unprofitable shepherds: Economic and theological perspectives on Ezekiel 34. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, 31(4), 493-504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309089207080055. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, M.C. 2010. Notfor profit: Why democracy needs the humanities (Vol. 2). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Redekop, C. 1982. Understanding Profits from the Christian Perspective. Direction Journal. [ Links ]

Register of private higher education institutions last update 24 October 2018 http://www.dhet.gov.za/RegistersocLib/Register%20of%20Private%20Higher%20Education%20Institutions%2024%20October%202018.pdf. (Date of access: 25 November 2018). [ Links ]

Ruch, R.S. 2003. Higher Ed, Inc.: The rise of the for-profit university. Baltimore: JHU Press. [ Links ]

Rüegg, W. ed. 2004. A history of the university in Europe. 3. Universities in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (1800-1945). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Schreiner, L.A. 2016. Re-Imagining Christian Higher Education: Hope for the Future. Christian Higher Education, 15(1-2), 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2016.1124713. [ Links ]

Shah, M. and Sid Nair, C. 2013. Private for-profit higher education in Australia: widening access, participation and opportunities for public-private collaboration. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(5), 820-832. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.777030. [ Links ]

Sandel, M. 2012. What money can't buy: the moral limits of markets. London: Allen Lane. [ Links ]

Sivaloganathan, M. 2018. Why And How You Should Run your Non-profit like a For-profit Organization. https://www.fastcompany.com/3041461/why-and-how-you-should-run-your-nonprofit-like-a-for-profit-organization. (Date of access: 20 November 2018). [ Links ]

Theron, P.M. 2013. The impact of Christian Higher Education on the lives of students and societies in Africa. Koers, 78(1), 1-8 [ Links ]

Tower of Philosophy woodcut from Gregor Reisch, Margarita Philosophica, c. 1503. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Gregor-Reisch-Margarita-philosophica - 4th ed. Basel 1517 - p. VI - Typus grammaticae - 500ppi.jpg. (Date of access: 20 November 2018). [ Links ]

Towner, P.H. 2006. The letters to Timothy and Titus. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, B.J. 2010. Wêreldwye belangstelling in Christelike wetenskapsbeoefening en Christelike hoër onderwys: hoe Afrika daarby kan baat. Journal for Christian Scholarship= Tydskrif vir Christelike Wetenskap,46 (1_2), 111-132. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, B.J. 2013. How not to internationalize - and perhaps secularize - Christian Higher Education. Potchefstroom: The institute for Contemporary Christianity in Africa. [ Links ]

Whittington, J.L. 2016. Biblical perspectives on leadership and organizations. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Morné Diedericks

morne.diedericks@aros.ac.za

Published: 15 Apr 2019

1 "Whatever was written in any of the fields of rhetoric or logic, geometry, music, or arithmetic, I could understand without any great difficulty and without the instruction of another man. All this thou knowest, O Lord my God, because both quickness in understanding and acuteness in insight are thy gifts. Yet for such gifts I made no thank offering to thee. Therefore, my abilities served not my profit but rather my loss" (Augustine, Confessions, 1976:111).

2 When referring to Christian Higher Education in this article, we are referring to higher education institutions with a Christian identity (Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, or Protestant) and purpose in their vision and mission. As a result, the vision and mission influence the institution's governance, curriculum, staffing, student body, and campus life.

3 These 131 institutions are only the institutions that offer qualifications on the National Qualifications Framework (NQF) between Levels 5-10. The levels are divided into the qualifications in the following manner:

4 Bryson (2018): Strategic planning for public and non-profit organizations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement; Freeborough and Patterson (2016J: Exploring the effect of transformational leadership on non-profit leader engagement; Berman (2014): Productivity in public and non-profit organizations.

5 Refer to Glanzer et al. (2017a): Restoring the soul of the university: Unifying Christian higher education in a fragmented age, especially chapters 12-16 with the theme "Reimagining the Christian University". Also refer to Schreiner (2016): Re-Imagining Christian Higher Education: Hope for the Future, and Hulme et al. (2016): Reimagining Christian Higher Education.