Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Koers

versão On-line ISSN 2304-8557

versão impressa ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.83 no.1 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.83.1.2254

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Spiritual formation towards Pentecostal leadership as discipleship1

Geestelike vorming onderweg na Pentekostalistiese leierskap as dissipelskap

Jeremy FellerI; Christo LombaardII

IDoctoral student: Christian Spirituality, Jniversity of South Africa

IIResearch Professor: Christian Spirituality

ABSTRACT

This contribution, a further development of the first author's recent thesis, investigates aspects of leadership in the Pentecostal tradition as it encourages discipleship. First contextualised broadly within unfolding post-secular sensitivities internationally and then contextualised specifically within the nature and history of Pentecostalism, the understanding of leadership and spiritual formation within the latter is then analysed. Leadership and spiritual formation within Pentecostalism are then developed towards an understanding of discipleship

Key concepts: leadership, Pentecostalism, discipleship, spiritual formation

OPSOMMING

Hierdie bydrae, n verdere ontwikkeling van die eerste outeur se onlangse proefskrif, ondersoek aspekte van leierskap binne die Pentekostalistiese tradisie onderweg na die aanmoediging van dissipelskap. Eerstens breedweg gekontekstualiseer binne internasionaal ontluikende post-sekulêre sentimente en daarna meer spesifi ek gekontekstualiseer binne die eie-aard en geskiedenis van die Pentekostalisme, word die verstaan van leierskap en geestelike vorming binne hierdie groepering geanaliseer. Leierskap en geestelike vorming binne die Pentekostalisme word ontwikkel in die rigting van n dissipelskapsbegrip

Kernbegrippe: leierskap, Pentekostalisme, dissipelskap, geestelike vorming

1. Sighs of the times

Playfully to misinterpret in combination Bible texts on creation that sighs and the signs of the times (e.g. Romans 8:19 and 2 Timothy 3:1), it seems that new times are upon us, and that at least some of us may sigh in relief at this. This new time has been labelled as a perhaps not initially-recognisable term of endearment, 'post-secularism' (cf. Habermas, 2008:17-29). In the preceding two broad cultural-historical 'phases' in Western/ised societies, the religious and the secular (the latter consisting of the academically widely and well-articulated modernist and post-modernist cultural trends) eras, matters of religious faith had in various ways been side-lined from public life at least (cf. Taylor, 2007, influentially). Within the presently perceptible post-secularist impulses, this is changing. God has become kosher again in the public sphere.

This, as indicated in Lombaard (2017):

...is not to be misunderstood as the end of secularism; that is, necessarily the end of (cf. Taylor, 2007),

• qualitatively: the privatisation of faith;

• quantitatively: dwindling numbers of adherents to religion or to a religion; and

• contextually: religio-socio-political environments that disable or enable certain expressions of religiosity.

Rather, post-secularism entails the slowly dawning diminishment of the explicit marginalisation of matters related to faith. No religious revival in the sense usually found within evangelical or charismatic circles is therefore implied here. Rather, a return of the religious dimension of life as a normal part of life is facilitated, towards a more neutral, natural position in which faith (also non-faith and anti-faith) is publicly encountered in society.

Thus, to summarise the sway of history with respect to the prominence afforded religion (Lombaard, 2016a:2):

With a pendulum that may have swung from implicit bias in favour of expressed religiosity in pre-secularist times to implicit bias in opposition to expressed religiosity during the secularist phase in Western/ised societies, a more natural kind of balance is now being sensed, or sought.

This religio-cultural balancing act is well captured by the 2010 subtitle of Kearney's increasingly influential Anatheism: returning to God after God (New York: Columbia University Press). Various signs of this unfolding era may be indicated (cf. Lombaard, 2015:86-89). However, related to the topic of leadership, this seems to be the case too. Kessler (2016) has namely indicated how in business management literature over recent decades concepts from religion has quite influentially been employed. Perhaps the popularly most recognisable of these are the ubiquitous corporate concepts of vision and mission, which at the very least echo the standard biblical-prophetic and ecclesial-missiological thought worlds. It is hence not surprising to find in such an unfolding cultural phase that, respectively, scholars of prophetic literature approach academically the topic of leadership (e.g. Wessels, 2015:657-677, on Jeremiah) while scholars of leadership also draw on Old Testament Studies (e.g. Kessler, 2004). This is not to say that the related languages of leadership and management should be uncritically accepted within religious life, as Ruthenberg (2005; also Kessler, 2016) has argued substantially. However, at the very least these current resonances in management and leadership thinking of concepts from the Bible and church life may be what Bailey (1997) had termed implicit religion: traces (to employ2 for the moment a term from Derrida, 1976) of faith language remain alive in modern meaning making. It may well be argued that such a somewhat minimalist language of observation, valuable as it is in certain instances (cf. Lombaard, 2016b:257-272), does not adequately capture the strength of this emerging merging of traditional God talk with modern leadership talk. This 'newspeak' (to reinterpret here positively the negative use of this phrase in Orwell's famous novel Nineteen Eighty-Four from 19493) is shown in for instance these five currently developing academic projects:

• 'Management of Meaning in Times of Organizational Change': 5th Conference on Church Leadership and Organizational change, 20-22 April 2016, LUX Centre for Humanities and Theology, Lund University, Sweden;

• 'Increasing Diversity - Loss of Control or Adaptive Identity Construction?' leadership conference, 29-30 April 2016, Leuven Centre of Christian Studies, Leuven, Belgium;

• Kok, J. (ed.) 2017. Leadership, Spirituality and Discernment. Leuven: Peeters.

• Spawn, K., Wright, A. & Herms, R. (eds) 2019a. Handbook to the Spirit in the Interpretation of Scripture, Part I: Methodological Studies. London: T&T Clark.

• Spawn, K., Wright, A. & Herms, R. (eds) 2019b. Handbook to the Spirit in the Interpretation of Scripture, Part II: Textual Studies. London: T&T Clark.

It seems apparent, from these and other signs, that the earlier (modernist and post-modernist) divide - even if it may have been conceptual in the public imaginary - between religion and other aspects of life, is being bridged; this, also in relation to the topic of leadership.

It may be misunderstood that such developments are part of a reactionary-conservative Christian milieu, vibrant in many circles internationally. Though in some respects that may be a valid characterisation, this is certainly not the only valid typology of these developments, for three reasons:

• First, in evangelical circles the acknowledgement that has been present for a long time, albeit in perhaps softer tones, is becoming more pronounced, that critical scholarship is not to be eschewed (cf. e.g. Synan, Yong & Asa-moah-Gyadu, 2016; Cox, 1996). This, interestingly, parallels precisely the growing awareness in what may for the moment be termed (admittedly too crudely) liberal scholarship, that reflexively to exclude confessionality from academia would be decidedly illiberal (with liberalism understood here in its classical sense of encouraging freedom to the fullest possible extent, thus opening the social arena to ever widening possibilities of diversity). The sense already with Bosch (1980:202-220; cf. Kritzinger & Saayman, 2011:120) that the divide between what he then termed the ecumenicals and the evangelicals can no longer be upheld, has in this just described rapprochement come to further fruition.

• Second, there have been changes in the ways faith is perceived and expressed within both broader society as much as within church circles. These changes mean that more complex faith-society interactions than the pre-modern 'faith is everywhere' and the modernist/post-modernist 'faith is nowhere' public reflexes become possible. (This is expanded upon in Lombaard, 2019.)

• Third, post-secularism entails also that insights from across the religious spectrum can more easily be drawn upon - though always, naturally, still critically weighed. The point is thus not that insights from whichever religious circles are accepted simply because they are from such circles; however, increasingly, insights from whichever religious circles are no longer reflexively ignored (or rejected) simply because they are from such circles.

With the unfolding religio-cultural scene thus set, the context for the further deliberations on the more specific topic of this article has been outlined.

2. Pentecostal spirituality

Pentecostal spirituality emphasises the present and continuous working of the Holy Spirit in the life of participants. This movement emerged from a combination of various theological traditions and social structures (cf. Robeck 2006). As a result the Pentecostal movement has global appeal4. The unifying factor is an emphasis on the involvement of the Holy Spirit in the individual lives of believers5. This movement is not theologically or structurally homogeneous (Anderson, 2004:9-15; Robeck 2006; Vondey 2013a, 2013b, 2010); this lack of theological unity within the movement thus gives one who engages in a study of this portion of Christianity a challenge clearly to identify an object of study. For the purposes of this article, the scope will be limited to Classical Pentecostalism6. This article namely seeks within this scope to address the value of spiritual formation for discipling Pentecostal leadership by exploring historical factors, addressing concerns and providing a pattern for such engagement.

3. Roots of Contemporary Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism emerged from various contributing elements of society and Christendom (cf. Burgess & McGee 1988). There are certain practices and beliefs that formed the foundation on which Pentecostals have developed (Neumann, 2012:197). Hollenweger (1997:144-180) asserts Roman Catholic theology had a significant influence in shaping the belief and practice of this movement. Pentecostals currently give emphasis to the supernatural as well as the spiritual, and temporal domains had a significant impact on shaping the Pentecostal worldview (cf. Nel 2015:1-7, 2014:291-309) Thus Pentecostals often exalt the one who has 'greater gifts' as one who has been empowered by the Spirit. The spiritual world is given primacy over temporal activities.

Almost all influential early leaders came from existing Protestant denominations (Dayton, 1987:35-60). Many of the beliefs of Pentecostals are derived from these Protestant denominations. Issues regarding the authority of Scripture, justification by faith and the priesthood of all believers are pivotal doctrines, yet often defined with a 'Pentecostal' flavour. Justification by faith, for example, is absolute, all the while affirming the responsibility of the believer - which Archer (2012:183) describes as biblical synergism. This provides a place for both Reformed and Arminian theology to have influence within Pentecostalism.

In addition to formative beliefs from prior movements, the most direct influence was from the holiness movement in America. These influencing bodies held an eschatological approach that provided motivation for their ministry and the necessity of the Holy Spirit's empowerment in days of a final 'end times harvest'. Consequently, missions proved to be an important activity to engage in with great haste. This has continued from the earliest days until the present. Due to the vital nature of mission, many aspects of long-term planning and thinking were rejected. Education was perceived to be unnecessary, for the Holy Spirit would help those who are involved. Accordingly, much of the Pentecostal community has rejected the place of education for those participating in ministry (cf. Nel 2016:1-9).

African tribal religious practices and beliefs influenced Pentecostalism also. The ecstatic worship and celebration are common throughout much of the Classical Pentecostal movement. The place of oral tradition is prominent, displayed through people who are encouraged to 'testify' on what has happened in their lives. The stories of God working in individual lives provides the opportunity for others to praise God and to look at their own life circumstances with hope. The elements of the own real-life context, with praise for the positives therein and hope for betterment of the negatives are vital elements within Classical Pentecostalism.

Although it is generally unhelpful to link each aspect of theology and practice to only one influence, the preceding paragraphs give insight into some of the significant influences that contributed to the Pentecostal movement: the emphases on both the supernatural and the real-life context, the influences of Protestantism and the holiness movement, and the issue of being led by the Holy Spirit only or by education too.

4. Development of Pentecostalism

Pentecostal history is generally linked to two key figures who were involved and were part of the holiness movement. Charles Fox Parham (1873-1929) had a Bible school in Topeka, Kansas. He assigned his students the task of examining the Scriptures to identify conclusive biblical evidence that one was filled by the Holy Spirit. The resulting doctrine became known as Initial Evidence: the initial evidence of being baptised in the Holy Spirit is speaking in tongues (glossolalia). The second key figure is William Seymour (1870-1922). Seymour, a black man, was permitted to attend Parham's school but sat outside the classroom due to segregation at the time. Seymour is generally identified as the instrumental person during the Azusa Street revival, which is the birth place of contemporary Pentecostalism. Seymour led the Azusa meetings and is seen by most as the father of Pentecostalism, though some debate may still be found.

The Azusa meetings were marked by intense preaching, long periods of prayer and, in a common formulation amongst Pentecostal adherents, 'waiting on God' (cf. Liardon, 2006). People came from near and far to participate and observe the strange activities that occurred (Cox, 1996:29). These participants engaged in the global task of mission, taking the message back to where they had come from and to nations around the globe (Kärkkäinen, 2002:877). They believed that God was pouring out the Spirit for a final harvest before Jesus' return. The early generation of Pentecostals thought little about long-term perspectives, since they believed in the imminent return of Christ. This resulted in little thought about what people should do subsequent to placing their faith in Christ and being filled with the Spirit.

Another generation of Pentecostals arose focusing on bringing heaven to earth. Healing evangelists, previously a part of Pentecostalism, rose to prominence. They brought forth hope at a difficult time in history, particularly in America, due to the preceding World Wars and the 1919 economic collapse (Wilson, 2002:440-441). The first generation emphasised the other world and the second generation sought to bring the message of hope to the temporal. It was a period of growth, particularly as Pentecostals used the new technology of mass-media, with many of their leaders embracing radio and television as a means to present their message. Pentecostals had previously published the stories of the work of the Spirit, however the publications had limitations. Mass media changed the way of life and Pentecostals embraced this significant way of communicating (Blumhofer and Armstrong, 2002:336).

A third generation of Pentecostals emerged. The powerful mass media presence was taken to new heights by these leaders. Sadly, the very same public platform of mass media broadcast the moral failure of certain leaders. The media that assisted in proclaiming the message also carried the stories of downfall. This caused many to question what was wrong and what could be done to draw these larger than life figures to accountability (Wan, 2001:153). Additionally, Classical Pentecostals participated in many revivals, perceived as a source of hope to the spiritual failures. The emphasis was most commonly on manifestations of the Holy Spirit. This drew much attention and continues to draw attention. Schools of the supernatural and other such ministry programmes emerged for Pentecostal ministry training. This coincided with the emphasis on the five-fold ministry. The gifts of Christ, found in Ephesians 4:11, became a prominent topic and cause for controversy. How are the gifts defined? Are they all in operation today? What are the ramifications for church leadership? Through all of these developments there was little focus on spiritual formation.

5. Leadership amongst Pentecostals

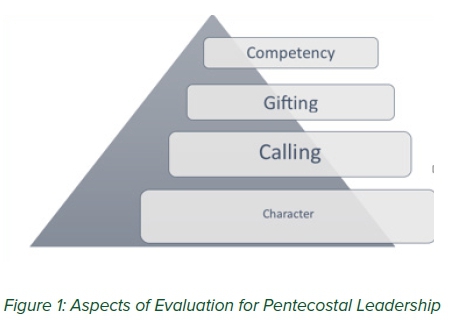

Pentecostals explore various aspects among individual leaders when seeking to promote and evaluate leadership.7 From the earliest days the sense of calling of a minister to participate in mission and ministry was expected. Additionally, the role of gifting8 rose to prominence. As the movement has matured, certain ministry skills, depending on the specific context, have risen to prominence. Across the movement there have been three major ways of evaluating leadership and promoting those who are deemed to have the necessary qualifications. All three can be clarified, developed and explored through formal and non-formal education (cf. Feller, 2015:17-20, 46, 49, 58-59, 101-102, 170-172, 237-241).

Underlying all three is the character of the individual (cf. Feller, 2015:174-176, 191-192). The assumption has been that character is automatic, because each person is a Christian. However, the public failures of prominent ministers have brought to light that one may not assume that the character is automatically acceptable. Thus, the issue of character in leadership is primary. The following diagram displays the importance of each aspect and the place of each in the development of leaders.

Leadership development has often emphasised specific skills. However, the necessary skills vary depending on the particular location and type of ministry one engages in. Therefore, the necessary skills of ministry effectiveness are not uniform. Additionally, the gifts one requires to fulfil his or her own calling are specific to the person and context one serves in. Finally, calling, what God asks one to do, is broad as it includes some aspects that most Christians will be asked to fulfil and yet is narrow enough to provide the individual with clarity as to one's own personal journey. Character, however, is uniform. The image of God is the goal and all believers have received this call. Therefore, spiritual formation for the whole person is necessary for Pentecostal leadership.

6. Concerns and objections to Spiritual Formation

Pentecostals, along with other Evangelicals9, have some concerns and objections to spiritual formation (cf. Feller 2015:50-54). Some challenge it due to theological beliefs while others express philosophical objections. Theologically a concern is raised about spiritual formation and justification by faith (cf. Feller 2015:50-54, 64, 75-76, 92-93). Pentecostals have affirmed a synergistic view of conversion (Archer, 2012:183; cf. Feller 2015:92-93, 145, 164, 175-176). However, the necessity of having responsibility for works causes some people concern.10Additionally, they raise fears of legalism rising, which was a problem in early Pentecostalism. Spiritual formation does not have to cause legalism, rather it embraces relationship with the Divine for the purpose of working out salvation in believers. The imputed righteousness of Christ is both positional and processional11. Concerns do exist in presenting people with the sense for performing certain activities and practices. However, attributing the works of a reborn person to the flesh is absent from Scripture. In fact, the Scriptures enjoin, in Pentecostal theology, the converted to do good works, because by works the believer will be judged (cf. Feller, 2015: 72, 132-135, 155-157, 241-242).

The place of grace in the theological belief system of Pentecostals also causes many to reject spiritual formation. The general belief about grace is that it is God's unmerited favour and covers the sin of those who place their faith in Jesus Christ. This definition falls short of the biblical usage. Cleary, grace is unmerited12 in the work of salvation. This, however, falls short of the role of grace in the life of converts. It is therefore beneficial to articulate the awareness of grace, as God's empowerment, to be understood in relation to three aspects of spiritual life. First, salvific grace is unmerited and brings an individual into relationship with God through Jesus Christ. Second, formative grace is empowerment of the Divine exercised in the life of a believer to bring one into the image of Christ. Finally, God empowers individuals for work and ministry with talents and spiritual gifts, which can be described as equipping grace. Consequently, all of life with God requires both Divine and human participants to work in synergy. Surely God leads, guides, speaks and directs, yet without personal decisions to act in response, nothing is accomplished.

Some Pentecostals, and other Evangelicals, object to participating in spiritual formation for philosophical reasons. Historically, Pentecostals have philosophically objected to Roman Catholic beliefs and practices. Many describe spiritual formation as Catholic, and thereby dismiss spiritual formation as having no value. However, such labels are of little use. The exercise must be examined from Scripture to discern the value and necessity of practices that one may engage in for spiritual maturity.

Another objection is that spiritual formation introduces practices from Eastern mysticism and the New Age movement into the church. This objection looks first at non-Christian practices and rejects them, rather than exploring practices in Scripture and engaging in those practices regardless of who else engages in similar practices. Additionally, many who object to spiritual disciplines, claim that spiritual formation is opposed to the authority and sufficiency of Scripture. The Scripture is the primary source for all of the spiritual journey and practices. Practices may be developed due to some historical pattern, which must be examined in light of the Scripture. The historical roots alone do not mean that these practices contradict the Scripture. A proper exploration of the Scriptures will lead one to identify the need, value and place of spiritual formation.

Spiritual formation is also objected to on the basis that it promotes works of righteousness. Works of righteousness are a necessity for one who has been regenerated. Obviously works of righteousness do not automatically produce spiritual formation, however it may be impossible to engage in spiritual formation without works of righteousness.

In many contemporary Evangelical communities there is concern regarding postmodernism and concomitant relativism. This concern has caused many to reject spiritual formation claiming it has emerged from this movement. Clearly this is not the case. A simple historical study will cause one to see the error of this objection. It cannot on the one hand be postmodern and relativistic and on the other hold to the historical faith and practices in church history. The rise of spiritual formation in current times may be a culturally sensitive response for many who desire a more holistic encounter with the Divine - an inherently post-secular move.

Pentecostals have placed a high value on mission and evangelism. They are concerned with the possible neglect of such activities in the pursuit of spiritual formation. This may be due to the lack of understanding of the nature and purpose of spiritual formation. The fullness of spiritual formation is developed as one lives out a normative life growing in the image of Christ. Consequently, those who grow in spiritual formation will engage effectively in evangelism and mission (in their various definitions) for the purposes of God.

Spiritual formation is essential for Pentecostal leadership. While there may continue to be some who reject it or proceed with caution, these objections can all be answered. Therefore, Pentecostal leadership should engage in spiritual formation, without fear, for the purpose of developing its leadership in the image of God13.

7. Pentecostal Spiritual Formation

Spiritual formation for Pentecostals is concerned with the work of the Holy Spirit in the process of forming believers in the image of Christ (Coulter, 2013:161). This holistic process informs the mind, conforms behaviour and transforms the inner being into the image of Christ. The mind will in Pentecostal theology learn the truth of Christ and grows under the Great Teacher. Conforming the body to Christ's behaviours will implement the standard of Christ in demonstrable actions displaying the Lordship of Jesus. The old nature is being taken off and the inner being transformed into the image of Christ (Colossians 3:9-10). The process is continuously engaged in and yet incomplete.

Generally, Pentecostals have engaged in intellectual discipleship of the mind or legalistic discipleship of behaviours. Both are much easier to evaluate as they have concrete measures to examine. Both of these means have been incomplete attempts, and largely unhelpful, since they were perceived to be complete activities of discipleship. For Pentecostal holistic discipleship, an appropriate means of evaluation is the fruit of the Spirit (Engstrom, 1976:187). Additionally, the fruit of the Spirit should be produced by one who is filled with the Spirit and in deep relationship with Christ (Clark, 2004:39).

Spiritual formation occurs, in Pentecostal theology, on three battle fronts; it is spiritual warfare (Willard, 2010:45). The three battlefields are the pattern of this world, demonic forces and the old nature (Ephesians 2:2-3). Each front in spiritual warfare presents unique attacks and means of engagement. The pattern of the world is subtle and one must not conform (Romans 12:2). The demonic battle is often displayed through various manifestations of the demonic. However, there are many levels of influence of the demonic in the life of a believer, often-oppressive thoughts (Warrington, 2012:82). The old nature or the flesh is also very subtle. Contemporary challenges arise when one senses or feels something that people will encourage him or her to pursue. However, such feelings may be the old nature and must be examined for its source.

The spiritual battles are fought through the use of spiritual disciplines. There are many spiritual disciplines that one may engage in for the purpose of changing the 'inward and spiritual reality', recognising that 'the heart is far more crucial than the mechanics' for growing in spiritual maturity (Foster, 1998:3). It is these spiritual disciplines that place one before God and cause the formation in the image of Christ to occur.

8. Necessary components for spiritual formation

Spiritual formation requires much from those who will participate and lead others to engage. Aimless participation in a selection of practices with the hopes that the end result will be the image of God is unrealistic (Waaijman, 2006b:43; cf., more substantially, Waaijman, 2002: 44-60, i.a.). Spiritual formation requires a clear goal, the image of Christ, and a process for one to participate in. This may challenge the worldview of some in Pentecostal leadership. Perceived absolutes may have to be evaluated and changed where necessary. Particular theological positions on salvation, works and grace should be examined more closely to align with biblical texts. The conclusion will in Pentecostal theology be a highly synergistic perspective with both the Divine and human sharing the responsibility. Additionally, fears should not cause one to reject spiritual formation. One may engage in an examination of the Scripture and historical practices to draw accurate conclusions. Additionally, one may participate in spiritual formation to strengthen intimate relationship with the Divine without fear that foundational truths will be eroded.

Direction is a practice of spiritual formation that Pentecostals may require yet struggle to seek. However, the absence of a director will require many to look beyond their denominational boundaries and into historical writings to gain help in spiritual maturity.

9. The way forward

Christian spirituality has the strength of diverse participants in the broader Christian Church to strengthen Pentecostal engagement in spiritual formation. The diverse approaches to the discipline provide the necessary room for Pentecostal participation without abandoning their values. Nevertheless, Pentecostals may hold a theological approach to studying spirituality (cf. Feller, 2015:128-192). However, if they choose to approach the discipline with openness, they may find Pentecostal spirituality is a counter-spirituality14, yielding much to the contemporary openness to spirituality (Waaijman, 2006a:10).

The role of spiritual formation towards Pentecostal leadership as discipleship has in this contribution been taken in review, first, with respect to the broader religio-cultural context of our times, which is becoming increasingly enabling of matters spiritual related to leadership issues. After that introduction, the central focus on Pentecostalism was engaged. The initial roots and, then, further development of Pentecostalism led in the argumentation followed above to a focus on leadership matters, with particular attention paid to different aspects related to spiritual formation.

Spiritual formation namely offers a primary component for the development of Pentecostal leadership. The discipleship of leaders cannot be left to chance or educational achievements.

Specific and intentional participation in spiritual formation is essential. Life in the Spirit, a hallmark of Pentecostalism, must include both the gifts and the fruit of the Spirit (Willard, 2006:28). Character transformation, the heart of spiritual formation, is manifested by the fruit of the Spirit in one's life. Winning the battle for the image of Christ is not instantaneous. It requires perseverance and maturity. The purpose is for the image of Christ to be formed in Pentecostal leaders.

10. Bibliography

Anderson, A. 2004. An introduction to Pentecostalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Archer, K.J. 2012. Salvation. (In Stewart, A., ed. Handbook of Pentecostal Christianity. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 180-186. [ Links ])

Bailey, E. 1997. Implicit religion in contemporary society. Kampen, Kok: Pharos. [ Links ]

Blumhofer, E.L. & Armstrong, C.R. 2002. Assemblies of God. (In Burgess, S. & van der Mass, E. eds. The new international dictionary of Pentecostal and charismatic movements. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. p. 333-340. [ Links ])

Bosch, D.J. 1980. Witness to the world. The Christian mission in theological perspective. Atlanta: John Knox. [ Links ]

Burgess, S.M. & McGee G.B. (eds.) 1988. Dictionary of Pentecostal and charismatic movements. Grand Rapids: Regency. [ Links ]

Clark, S.B. 2004. Charismatic spirituality. Cincinnati: St. Anthony Messenger Press. [ Links ]

Coulter, D.M. 2013. The whole gospel of the whole person: ontology, affectivity, and sacramentality. Pneuma, 35:157-161. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/15700747-12341346 [ Links ]

Cox, H. 1996. Fire from heaven: the rise of Pentecostal spirituality and the reshaping of religion in the twenty-first century. London: Cassell. [ Links ]

Dayton, D.W. 1987. Theological roots of Pentecostalism. Metuchen: Hendrickson Publishers. [ Links ]

Engstrom, T.W. 1976. The making of a Christian leader. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Feller, J.A. 2015. Spirit-filled discipleship: spiritual formation for Pentecostal leadership. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (D.Th. Christian Spirituality thesis. [ Links ])

Habermas, J. 2008. Secularism's crisis of faith: notes on post-secular society. New Perspectives Quarterly 25:17-29. [ Links ]

Foster, R.J. 1998. Celebration of discipline. New York: Harper One. [ Links ]

Hollenweger, W.J. 1997. Pentecostalism: origins and developments worldwide. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [ Links ]

Kärkkäinen, V.M. 2002. Missiology: Pentecostal and Charismatic (In Burgess, S. & van der Mass, E. eds. The new international dictionary of Pentecostal and Charismatic movements. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. p. 877-885. [ Links ])

Kearney, R. 2010. Anatheism: returning to God after God. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Kessler, V. 2017. "'Visionaries... psychiatric wards are full of them': Religious terms in management literature." Verbum et Ecclesia 38 (2): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v38i2.1649 [ Links ]

Kessler, V 2004. Ein Dialog zwischen Managementlehre und alttestamentlicher Theologie: McGregors Theorien X und Y zur Führung im Lichte alttestamentlicher Anthropologie. Pretoria: University of South Africa. (D.Th. Practical Theology thesis. [ Links ])

Kritzinger, JNJ & Saayman, W 2011. David J. Bosch: prophetic integrity, cruciform praxis. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Kok, J. ed. 2017. Leadership, spirituality and discernment. Leuven: Peeters. [ Links ]

Liardon, R. 2006. The Azusa Street Revival. Shippensburg: Destiny Image Publishers. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2019. A Next TIER: Interdisciplinary in Theological Identity / Education / Research (TIER) in a Post-Secular Age. Paper presented at the 'School of Social Sciences Conference', 2-3 September 2015, UNISA, Pretoria, and at The Interplay between Theology and other Disciplines in Research and in Theological Education' conference, 14-16 April 2015, Faculty of Theology, University of Latvia, Riga. (In volume edited by Asproulis, A. Athens: Volos Academy for Theological Studies. Forthcoming: 2017. [ Links ])

Lombaard, C 2016a. Theological education, considered from South Africa: current issues for cross-contextual comparison. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 72(1):1-5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i1.2851 [ Links ]

Lombaard, C 2016b. The absence of God as characteristic of faith: The concept of Implicit Religion of Edward Bailey (1935-2015). Stellenbosch Journal of Theology, 2/2:257-272. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2015. 'And never the twain shall meet? Post-secularism as newly unfolding religio-cultural phase and Wisdom as ancient Israelite phenomenon. Spiritualities and implications compared and contrasted. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa, 152:82-95. [ Links ]

Lombaard, C. 2011. Biblical Spirituality and human rights. Old Testament Essays, 24(1): 74-93. [ Links ]

Nel, M. 2016. Rather Spirit-filled than learned! Pentecostalism's tradition of anti-intellectualism and Pentecostal theological scholarship. Verbum et Ecclesia, 37(1): 1-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v37i1.1533 [ Links ]

Nel, M. 2015. An attempt to define the constitutive elements of a Pentecostal spirituality. In die Skriflig 49(1): 1-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v49i1.1864 [ Links ]

Nel, M. 2014. A critical evaluation of theological distinctives of Pentecostal theology. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae, XL(1): 291-309. [ Links ]

Neumann, P.D. 2012. Spirituality. (In Stewart, A. ed. Handbook of Pentecostal Christianity. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 195-201. [ Links ])

Orwell, G. 1949. Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Secker & Warburg. [ Links ]

Robeck, C.M. 2006. The Azusa Street mission and revival: the birth of the global Pentecostal movement. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. [ Links ]

Ruthenberg, J.T. 2005. Contemporary Christian spirituality: its significance for authentic ministry Pretoria: University of South Africa. (DTh Christian Spirituality thesis. [ Links ])

Spawn, K., Wright, A. & Herms, R. eds. 2019a. Handbook to the Spirit in the interpretation of Scripture, Part I: methodological studies. London: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Spawn, K., Wright, A. & Herms, R. eds. 2019b. Handbook to the Spirit in the interpretation of Scripture, Part II: textual studies. London: T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Synan, V., Yong, A. & Asamoah-Gyadu, K. eds. 2016. Global renewal Christianity: Spirit-empowered movements past, present, and future, III: Africa and Diaspora. Lake Mary, Fla.: Charisma House Publishers. [ Links ]

Taylor, C. 2007. A secular age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Vondey, W. 2013a. Pentecostalism: a guide for the perplexed. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Vondey, W (ed.) 2013b. Pentecostalism and Christian unity. Volume 2: Continuing and building relationships. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications. [ Links ]

Vondey, W (ed.) 2010. Pentecostalism and Christian Unity. Volume 1: Ecumenical Documents and Critical Assessments. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K. 2002. Spirituality: forms, foundations, methods. Leuven: Peeters. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K. 2006a. What is Spirituality? (In De Villiers, P.G.R., Kourie, C.E.T. & Lombaard, C. eds. The Spirit that moves: orientation and issues in spirituality. Acta Theologica Supplementum, 8:1-18. [ Links ])

Waaijman, K. 2006b. Conformity in Christ. (In De Villiers, P.G.R., Kourie, C.E.T. & Lombaard, C. eds. The Spirit that moves: orientation and issues in spirituality. Acta Theologica Supplementum 8:41-53. [ Links ])

Wan, Y.T. 2001. Bridging the gap between Pentecostal holiness and morality. Asian Journal of Pentecostal Studies 4(2): 153-180. [ Links ]

Warrington, K. 2012. Exorcism. (In Stewart, A. ed. Handbook of Pentecostal Christianity. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 81-84. [ Links ])

Wessels, W.J. 2015. Leaders and times of crisis: Jeremiah 5:1-6 a case in point. Tydskrif vir Semitistiek / Journal for Semitics 24(2): 657-677. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25159/1013-8471/3474 [ Links ]

Willard, D. 2006. The great omission: reclaiming Jesus. Essential teachings on discipleship. New York: Harper One. [ Links ]

Willard, D. 2010. The Gospel of the Kingdom and spiritual formation. (In Andrews, A. ed. The Kingdom life: a practical theology of discipleship and spiritual formation. Colorado Springs: NavPress. p. 27-57. [ Links ])

Wilson, D.J. 2002. William Marrion Branham. (In Burgess, S. & van der Mass, E. eds. The new international dictionary of Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. p. 440-441. [ Links ])

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Christo Lombaard

Published: 21 Aug 2018

1 This joint article constitutes further work from the UNISA doctoral dissertation in Christian Spirituality of the first author, Feller, completed under the supervision of the second author here, Lombaard; cf. Feller, 2015.

2 Derrida's use of the term refers to the instability of meaning: each attempt at expressing meaning is afloat in a sea of historical impulses forming it, and thus loses determinacy - the post-modernist (and surprisingly mystical) essence, thus. Here, the direction of intent with the term 'traces' is reversed: words retain memory of earlier meanings, which may not explicitly be realised or intended when those words are used, but that are nevertheless present, even if such meanings are subdued, implied or forgotten (a Freudian slip kind of moment).

3 In this novel by Orwell, 'newspeak' refers to dictatorial^ controlled language. Here, the term is put to different use: to describe closer integration of two earlier more separated public 'languages'; here, those of religion and leadership.

4 The whole movement does not have global appeal, but aspects of it do. Consequently, many participants around the globe latch on to certain points and identify as Pentecostals.

5 There is not a unified Pneumatology amongst Pentecostals; rather Anderson (2004:187-205) points out the emphasis on the Spirit is the unifying theme, even if the respective theologies differ.

6 Classical Pentecostals generally formed denominations, which they prefer to describe as fellowships and trace their roots to the Azusa Street Revival in 1906. Additionally, some indigenous movements around the globe later joined to Classical Pentecostalism by self-identifying as such. Thus, they are clearly identifiable.

7 Educational qualifications have become the normal procedure, however this is not universal for Classical Pentecostals, whereas three others (see subsequent paragraphs) seem to be.

8 Pentecostals emphasize spiritual gifts. Historically, the spiritual gifts in 1 Corinthians 12 are primary. In the late twentieth century gifts in Ephesians 4 rose to prominence, particularly relating to the role of these gifts in leadership.

9 Here meant in the English sense, rather than the German word for Protestantism.

10 Concerns relate to the finished work of Christ. The question asked is, what can a person do to add any value to the work of Christ?

11 The imputed righteousness of Christ places one in the right relationship with the Divine. Additionally, the convert is called to obedience and thereby lives out the righteousness of Christ.

12 In salvation, there is nothing that one can do to earn God's grace, therefore it is unmerited. Certain good works do not create relationship with God, this is provided through the sacrifice of Christ.

13 For a more extended discussion of the important topos of the imago Dei in Christian theology, see Lombaard 2011:81-87.

14 In spirituality, counter-movements develop in resistance to the status quo, challenging the culture, society or religious powers.