Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Koers

On-line version ISSN 2304-8557

Print version ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.82 n.1 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.82.1.2220

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Transformative learning through teacher collaboration: a case study

Transformasionele Leer Deur Middel Van Onderwysersamewerking: 'n Gevallestudie

G.M. Steyn

Department of Educational Leadership and Management, University of South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article, which developed from previous studies at the school, reports on a qualitative study aimed at investigating the professional learning experiences of staff members at a South African primary school. Transformative learning and adult learning theory underpinned the study. Data were collected by means of an open-ended questionnaire administered to teachers of the Mathematics department, a focus group interview with these teachers and individual interviews with the principal. Participants indicated that teacher collaboration enhanced their professional learning in the various horizontally and vertically structured teams at the school. They emphasized the importance of effective communication, trust and respect in their interpersonal relationships. Although participants acknowledged differences in their personalities and professional approaches, they regarded them as beneficial and complementary for their learning. The study showed that transformative learning was contextualised and therefore suggested that more research should be carried out to explore the contextual factors that promote sharing of knowledge and skills among teachers at other schools.

Key words: Adult learning; transformative learning; teacher collaboration; professional development

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel wat uit vorige studies in die skool ontwikkel het, doen verslag oor 'n kwalititiewe studie wat die professionele leerervaringe van personeel in 'n Suid-Afrikaanse laerskool ondersoek het. Transformasionele leer en volwasseneleerteorie het as grondslag van die studie gedien. Data is ingesamel deur middel van oop vrae in 'n vraelys aan onderwysers in die Wiskundedepartement, 'n fokusgroeponderhoud met hierdie onderwysers asook individuele onderhoude met die skoolhoof. Deelnemers het aangetoon dat onderwysersamewerking hulle professionele leer verbeter het in die horisontale en vertikale strukture in die skool. Hulle het die belangrikheid van effektiewe kommunikasie, vertroue en respek in hulle interpersoonlike verhoudinge beklemtoon. Alhoewel deelnemers verskille in hulle persoonlikhede en professionele benaderings erken het, het hulle dit as voordelig en komplementerend beskou. Die studie het aangetoon dat transformasionele leer gekontekstualiseerd is en dat verdere studies derhalwe aanbeveel word om die kontekstuele faktore wat die bevordering van kennis en vaardighede onder onderwysers bevorder, te ondersoek.

Kernbegrippe: Volwasseneleer; transformasionele leer; onderwysersamewerking; professionele ontwikkeling

1. Introduction

During the past four decades scholars have generated powerful theoretical frameworks to gain a better understanding of the ways in which adults develop and learn (Forte & Flores, 2014; Newman, 2014; Nohl, 2015; Johnson, Stribling, Almburg, & Vitale, 2015: Rickey, 2008; Smith, 2014; Taylor, 2007). In education more emphasis than ever is now being placed on increasing teachers' individual and collective competencies for the sake of achieving quality teaching and learning in schools (Wells, 2014:489).

However, recent studies on continuing and adult education have revealed that the current dialogue on teacher learning has overlooked the way in which teachers at "high-functioning schools interact and work together to produce successful outcomes" (Poulos, Culberston, Piazza, & D'Entremont 2014:28). In line with this view, Dadds (2014:10) states that 'delivery' models incorrectly believe that 'good practice' does not come from inside schools and that teachers should rather adhere to the decisions made centrally by different professional and other bodies. Such an approach is very limited since it negates the vital role of teachers' experiences in the development of their practice (Dadds 2014:10). Poulos et al. (2014:29) support the view that teachers prefer to work with their peers in order to support their practice.

In view of the dire need to improve the quality of education in South Africa, Botha (2012) advocates the implementation of learning communities in schools. The Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development in South Africa states that a professional learning community model should be introduced in all public schools by 2017 (South Africa, 2011:82). The vision for the future of this framework is illustrated by the case of a Grade 6 Mathematics teacher in a rural South African school in the year 2040 who collaborated with colleagues at her school to improve her learners' academic performance (Republic of South Africa 2011:78). Moreover, the most recent initiative, the 1+4 teacher development plan, aims to improve the academic performance of Mathematics learners in the senior phase (Republic of South Africa, 2015:1). This teacher development plan is of special interest since it is based on the concept of professional learning communities (Republic of South Africa, 2015:1) which was also the focus of this study. However, suitable empirical studies on the effective implementation of this model in South African schools are largely lacking, which confirms the need to conduct such a study.

This study presents findings from an extended study which had previously focused on various aspects of teacher collaboration within a particular school (Steyn, 2013; 2014a; 2014b). It attempted to explore the collaborative learning experiences of teachers in a particular department at a primary school and describe the aspects that supported or inhibited their transformative learning. The research problem that emanated from the above was: How can the interplay between the individual teachers' developmental capacity and their capacity to engage in collaborative practices be illuminated by means of the developmental foundations of collaborative learning practices? The notion of teachers' transformative learning is well worth investigating since it has benefits for both the school and system-wide sustainable improvement and capacity-building, which ultimately leads to improved student learning. Moreover, despite the various studies on teachers' transformative learning, new reflections on transformative learning are required since this would have the potential to benefit teachers in both the theoretical and the practical realms (Nohl, 2015:47; Johnson et al., 2015:15; Matamala, 2013:5). In line with this view, Taylor and Cranton (2013:44) consider transformative learning "as a theory in progress" which needs to be expanded.

2. Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework for this study was derived from the literature on adult learning theories and transformative learning since they underpinned the attempt to understand how teachers as adults experience collaborative learning aimed at their professional development (Drago-Severson 2007:80; Rickey 2008:39). Scholars show that adults bring work and life experiences to their workplace learning, which then shape their perspectives on professional learning (Drago-Severson, 2007; Knowles, 1986; Mezirow, 2003; Mockler & Normanhurst, 2004). Adult learning theories illuminate how the process of learning can support change and assist in understanding how to support changes in the knowledge, skills, behaviours, abilities and even sense-making systems (Drago-Severson, 2007:75). Moreover, adult learning theories also shed light on how adults can be better supported in their professional development (Drago-Severson, 2007:75). The principles of adult learning include the following (Drago-Severson, 2007:76; Merriam, 2001:5):

1. Self-concept: Adults are internally motivated and able to direct their own learning.

2. Experience: Adults have accumulated knowledge and life experiences that serve as a valuable learning resource. The professional learning of adults, which is essentially a social experience, is nurtured by means of exploration, exchange and formulation of new viewpoints and ideas (Dadds, 2014:14).

3. Orientation to learning: Adults' orientation to learning arises primarily from their need to identify and solve problems collaboratively within real-life situations.

4. Readiness to learn: Adult learners value the process of learning and see it as a growth process through which they can reach their full potential.

The concept "transformative learning" was initially theorised by Mezirow (1991), who built upon adult learning theory. The scholarly work on transformative learning has since been grounded in the seminal work of Mezirow (Nohl, 2015:35) and has developed into one of the most studied theories in the adult education field during the past three decades (Santalucia & Johnson, 2010:CE-2; Taylor, 2007:173). Mezirow sees an individual's transformative learning as a "paradigm shift" since it leads to a shift in an adult's meaning perspective once such an adult engages in interactive activities that enhance his/her own worldview (Matamala, 2013:5; Taylor, 2007:174). Santalucia and Johnson (2010:CE-3) isolate a triggering event as the key to transformative learning, which then serves as a catalyst in which adults are stimulated to examine their beliefs. Because transformative learning is defined as a meaning-making adult learning process that brings about fundamental changes, it is necessary to understand how these processes develop over time (Drago-Severson, 2008:60; Rickey, 2008:31; Nohl, 2015:35; Taylor, 2007:174). In this regard Drago-Severson (2007:74) states that successful development of teachers requires more than increasing their knowledge and skills (informational learning). The challenges in schooling require "changes in the way adults know, that is, transformational learning" (Drago-Severson 2007:74). Taylor and Cranton (2013:33-38) identify three central constructs of transformative learning.

1. Experience: The experiences of individuals form the basis of their values and beliefs and constitute "a starting point for discourse" (Mezirow, 2000:31). Moreover, this implies that individuals' ways of knowing will determine how they understand their responsibilities and roles as well as the types of professional support they require from colleagues to develop from collaborative learning opportunities (Drago-Severson, 2008:61).

2. Empathy: Empathy plays an important role "in engaging the emotive nature of transformative learning" (Taylor & Cranton 2013:37). It enables learners to comprehend the perspectives of others and increases the opportunity of learners to reach a shared understanding of issues (Taylor, 2007:182).

3. Desire to change. The desire to change and to act refers to the step individuals are required to take as they shift from reflection to transformation. Moreover, a crucial component of transformative learning is the necessity to translate it into action (Rickey, 2008:31; Taylor, 2007:181).

The transformative learning theory is based on humanist and constructivist suppositions (Newman, 2014:352). Humanism presupposes that humans are autonomous and free and that they have the potential for development and growth (Taylor & Cranton, 2013:39). Various scholars have voiced their suppositions and criticism of constructivism as a theory of learning (Bryant & Bates, 2015; Fosnot, 2005; Gemeda, Fiorucci & Catarci, 2014; Liu & Matthews, 2005; Richardson, 2012; Rout & Behera, 2014). Liu and Matthews (2005:387) claim that constructivism emerged as the leading theory of human learning because the behaviourist and information-processing approaches in the 1980s and 1990s "failed to reflect either the active role of the learning agent or the influence of the social interactive contexts in everyday educational settings'"

Constructivists view learning as a process in which personal meaning is actively constructed in the human mind and is shared on the basis of experiences which are validated through interaction with others and which involve an active individual and social construction of meaning (Fosnot, 2005:1; Gemeda et al., 2014:75; Richardson, 2012:1625; Rout, 2014:9; Wells, 2014:490). Liu and Matthews (2005:387) distinguish between cognitive/radical constructivism and social constructivism. Cognitive/radical constructivists focus on individuals and discovery-oriented learning processes, while social/realist constructivists view learners as being "enculturated" into their learning community where they construct knowledge based on their present understanding through their interaction with others (Liu & Matthews, 2005:388). Richardson (2012:1625) supports Liu and Matthews' 2005 view of social constructivism that focuses on how the creation of formal knowledge develops. However, he sees psychological constructivism as the creation of meaning within an individual's mind, and more recently on the way in which shared meaning develops within a group (Richardson, 2012:1625), which is also supported by this particular study.

Rout and Behera (2014:9) who revisited professional development of teachers within a constructivist framework, offer a shift away from the mechanistic world-view to a more holistic world-view that involves the constructivist and social or contextual approach of teacher professional development. Constructivist professional development give teachers an opportunity to express their view of student learning (is learning a constructive process?), of teaching (is the teacher a facilitator or orator and what is the teacher's understanding of the curriculum content?) and of professional development (is a teacher's own growth as well as his learning best approached through a constructivist orientation?) (Hoover, 1996). Of particular interest to this study is the constructivist socio-cultural approach where individuals obtain new knowledge when appropriate opportunities in a conducive environment allow for professional dialogue and the exchange of experiences and ideas (Valdmann, Rannikmae & Holbrook, 2016:287). This is in line with the view of Bryant and Bates (2015:17) who claim that they support a social constructivist approach to learning because they believe that teachers make sense of their world by constructing knowledge through their various interactions with other teachers. Engstrom and Kabes (n.d.:14) elaborate on this view by stating that teachers' dialogue with colleagues in a learning community has the potential to bring about changes in their classroom practices. Being part of a learning community, teachers challenge and examine the views of others that begins "the transformational process in which new and deeper understandings replace what have become inadequate beliefs about teaching and learning" (Engstrom & Kabes, n.d.:15). Their collaboration is therefore utilised as a means to transformative learning (Engstrom & Kabes, n.d.:14). For Williams (2010:143), in the case of teachers this "pooled intelligence of teachers is immense"

Two conditions are required for a team of professionals to experience transformative learning:

1. Transformative learning requires a nurturing learning environment in which learning is contextualised (Katz & Earl, 2010:29, 32; Taylor 2007:188; Wells, 2014:493). In essence this condition refers to the role of relationships in transformative learning. Mezirow (2000:11) accepts the importance of relationships in transformative learning, as "effective participation in discourse and in transformative learning requires emotional maturity, awareness, empathy, and control.... [and] knowing and managing one's emotions, motivating oneself, recognizing emotions in others and handling relationships".

2. Mutual trust in team members and in the meaning-making process is required (Taylor, 2007:179). Mockler and Normanhurst (2004:7) call for "a reinstatement of trust" for transformative learning to occur. According to them this will allow teachers to openly acknowledge their professional learning needs, and to collectively work with other team members to continuously develop their expertise and understanding. In the presence of trustful relationships individuals feel free to be involved in discourse and share information to achieve consensual and mutual understanding (Forte & Flores, 2014:98; Poulos et al., 2014:29; Watson, 2014:25).

3. School context

The particular Afrikaans urban primary school examined in the study was selected because of the school's emphasis on teacher collaboration, as was discussed in relation to previous studies carried out in the school. The study formed part of an on-going project on the professional development of teachers at a purposefully selected school. The primary school in the study is located in an urban area in Gauteng with approximately 1 850 learners and 129 teachers at the time of the study (including the 18 teacher assistants for classes in the foundation phase. The teacher collaborative structure became dominant in 2011 after the appointment of a new principal. He emphasised collaboration between teachers for the sake of improved teacher and student learning. The school arranged various teaching teams which included departmental teaching teams and teaching teams in the various grades. In this study the focus was on teachers in the mathematics department.

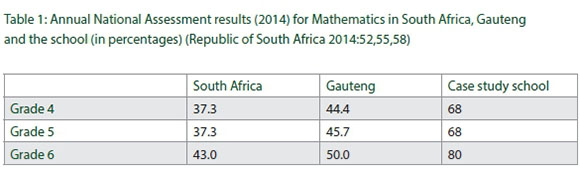

The school participated in the Annual National Assessment for Mathematics and Table 1 shows results for all South African schools, Gauteng schools and the case study school. As indicated in the table, learners performed significantly better than the country average and the average for Gauteng.

4. Research design

The study employed a qualitative case study approach to investigate the role of transformative learning in the process of knowledge acquisition and skills development in the mathematics department at the school (Johnson et al., 2015:6). Purposeful sampling was employed for the investigation since previous studies revealed that the school had moved towards a professional learning community model (Steyn, 2013; 2014a; 2014b; 2015). Two criteria for selecting the team of mathematics teachers were applied: (1) The Mathematics department consisted of seven Grade 7 classes, seven Grade 6 classes and eight Grade 5 classes, making it the largest department in the school. (2) The larger number of teachers in these grades also required a degree of interdependence among them to strengthen their horizontal and vertical collaboration.

In this study the researcher used a socially constructed knowledge base (Creswell, 2013:24) to allow participants to express their perceptions of their learning experiences in teams (Williams, 2010:66). This approach helped the researcher to understand the world in which participants worked and also added richness and rigour from the perspective of participants (Blacklock, 2009:147).

Data were collected in 2014 and 2015, using a focus group with teachers in the Mathematics department, an open-ended questionnaire for the principal and teachers and also individual interviews with the principal, who implemented the teacher collaboration structure in 2010. These methods of data collection allowed participants to reflect on their learning experiences in the mathematics department (Gemeda et al., 2014:75). The interview schedule and questions in the questionnaire were predominantly based on the theoretical framework (Gau, 2014:449) and were general and broad enough to ensure that participants were able to construct meaning on particular aspects (Creswell, 2013:25). Triangulation of data obtained by various data collection methods ensured the validity of the study (Gemeda et al., 2014:76).

Transcriptions from the audio-recordings were used to label raw data and identify codes and themes (Creswell, 2013:190; Gau 2014:449). The focus in the data analysis was on the transformative learning of teachers collaborating in teams in the department (Rosnida & Malakolunthu, 2013:561). A thematic analysis, in particular using an inductive approach, was employed in the data analysis (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006:4; Onwuegbuzie, Leech & Collins, 2012:22). Furthermore, the thematic analysis that was conducted within the social constructionist framework involved a search for links between themes (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006:4; Gemeda et al., 2014:76; Onwuegbuzie et al., 2012:22).

Data management in the form of coding and identifying themes was based on the conceptual framework of the study, that is, transformative learning (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006:4). It included the following steps: (1) familiarisation to identify codes and topics after an overview of the content; (2) constructing an initial thematic framework to refine the codes and topics into themes; (3) indexing and sorting sections of the data that were linked to one another; and (4) reviewing data extracts to promote refinement of the data by ensuring that the extracts revealed similarity. Moreover, in vivo coding was used for themes to ensure that participants' own words were respected (Creswell, 2013:185). Member checking was done to validate the accuracy of findings and to provide an opportunity to correct and make additions to the data.

Ethical considerations for the study included the following: Participation in the study was voluntary and the aim of the study was explained to all participants. Participants were assured of their anonymity in the presentation of the findings. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Department of Education and the University of South Africa.

5. Findings

5.1 The nature of transformative learning: "I learn from my team members"

Teachers brought their own frame of reference and ideas to their teams. However, their "passion" for Mathematics was a recurring theme in their responses, which they voiced as the reason for their successful collaboration and also as a requirement for effective teacher collaboration.

With smaller classes in Mathematics in Grades 5 to 7, where four or five teachers taught in the same grade, teachers were "compelled" to work together to ensure consistency in the same grade. There was also continuity among the different grade teachers which enabled teachers to prepare learners better for the next grade and even for the future. In this regard the principal explained:

The members of teams have to work together to succeed as a team. In the Mathematics Department as well as in the Foundation Phase, there are very well-structured avenues of communication between the different role-players. For example, the Grade 6 educators have to know exactly what the Grade 7 educators expect from their learners ... There is no need for children to be intimidated and/or frightened by the new academic year.

Although participants agreed on the necessity of teacher collaboration, they voiced different experiences of the nature of collaboration. A teacher who joined the school at the beginning of 2014 was convinced that she had learnt a lot as an individual professional, and that she had also learnt to work in a team since joining the school.

The idea of interdependence was raised by another teacher, who felt that the teachers "needed" one another to measure their "own professionalism and approach to teaching and to ensure that other teachers are on the right track by assisting them with the right equipment to attain the goal". Their collaboration helped to give teachers exposure to many ideas and approaches and to adapt their own approach and incorporate new ideas into their classroom practice to "ensure greater success". This also ensured their "own professional growth" since their collaboration allowed team members to draw upon the "individual strengths" and expertise of others. One teacher elaborated on this view:

Collaboration changes the approach to teaching. This is possible because of the exposure to other team members' ideas and approaches. One educator explains fractions with a different approach to one's own, which might be the way that some learners in the classroom, who have not yet grasped fractions in the way that you have explained it, will understand the concept better. The number of learners reached while explaining fractions then doubles.

Participants were clear about their goal in collaboration. For the principal this was a prerequisite for teacher learning: "They [the teachers] have to understand the goals; they have to support the vision." He explained how their shared goals influenced teachers' success.

We [the school management team] noticed that some educators who have "lost" their motivation during the course of their careers, have seemed to "refocus" now. This is primarily because of our substantial effort to help them to see the big picture of what we are busy with, and working together towards that goal.

For teachers the "ultimate goal" of teacher collaboration was described as ensuring that teaching and learning outcomes would be attained and that it should lead to the success of learners, both "academically and emotionally". They also wanted to help learners to "love the subject" and to lay the "right foundation" that would lead to improved learner performance. Although one teacher agreed that the mathematics teachers shared the same goals, she indicated that there was "room for improvement" which could be considered as an area for development, especially in the light of the principal's view:

Without professional collaboration, there can be no growth; no advancement; no development; no refinement; no synergy... The whole is more than the parts, and the system cannot function if all the parts do not work together. There is not a single entity in the school that can stand on its own. Everything is interconnected, and thrives and succeeds when in collaboration with other systems within the school.

The principal attributed the success of teacher learning and collaboration in their school to the fact that teachers had "embraced the idea" of collaboration, had taken "ownership of the total picture" to achieve their shared goal and had "bought into the bigger picture".

The findings suggest that participants agreed on the necessity for teacher learning through teacher collaboration, which concurred with the study of Williams (2010:146). Participants were involved in active individual and social construction of meaning and this contributed to their transformative learning (Drago-Severson, 2007:76; Gemeda et al., 2014:75; Santalucia & Johnson, 2010:CE1; Wells, 2014:490). They also realised that their collaboration validated their individual practices and encouraged a collaborative focus and even a "refocus" on student learning goals (Williams, 2010:139), which influenced their sense of ownership (Wells, 2014:490).

The goal of teacher collaboration in the school was to improve teaching practice for the sake of enhanced student performance (Greer, 2012:71). This proved their readiness to learn and to value their learning as a growth process (Drago-Severson, 2007:76). The essential drive to improve their practice was well fostered by the "multiple-perspective exchange of views and ideas" (Rosnida & Malakolunthu, 2013:567) on various mathematical topics. In this regard Drago-Severson (2007:89) states that adults with different perspectives will experience collaboration differently, but that they will benefit from team members who offer different kinds of assistance and views that will ultimately influence their professional growth. Like the study by Rosnida and Malakolunthu (2013:567), this study showed that teachers believed that their collaborative learning had a meaningful impact on their practice, apparently because of teachers' natural ability to learn as adults.

5.2 Sharing professional practice: "Ideas and strategies are shared that provide opportunities to learn new things"

The school formally structured vertical and horizontal team meetings to allow teachers to debate mathematical issues since such debates could potentially promote professional learning among teachers. Structured meetings of grades teachers took place on a monthly and weekly basis; team members of the Mathematics department met at the beginning of each semester. As a department they planned the work that had to be done in the department and allocated and divided responsibilities related to their teaching. This arrangement not only ensured continuity between different grades but also consistency within classes in a particular grade. In this regard the principal stated:

The success in the collaboration between the different grades makes me very proud. Where the different grades were in competition with each other some years ago, that is no more the case. They understand their interdependency of each other, and they embrace it.

One teacher found this approach so successful that she expressed her desire to meet with neighbouring high schools to hear how the schools' learners were progressing in the higher grades, so that the primary school teachers could better prepare their learners for high school.

Two teachers explained how their teams functioned:

• We have one educator who takes the lead for a grade. Every educator that is part of that team contributes ideas and assessment tasks. These contributions are integrated by the lead educator ... Every educator is, however, entitled to suggest alternatives.

• Our team meets regularly to discuss matters, provide advice and make an effort to know each other... Ideas and strategies are shared that provide opportunities to learn new things and new strategies for teaching from each other . in doing this, outcomes are reached and we attain success as a team.

It was clear from their views that structured, continuous support was required to ensure the establishment of a conducive and healthy working environment. One teacher, however, expressed the need for more guidance in her particular team. This view was opposed by other teachers, who felt that it was an individual's responsibility to ask for advice and guidance.

Many participants acknowledged the positive changes in their classroom practice that resulted from sharing their practices. From the principal's point of view as a supervisor, he said he was convinced that teaching practices at the school "substantially" improved as a result of collaboration between teachers. Participants also referred to the expansion of their teaching repertoire in relation to a specific content area, especially in the teaching of fractions. Moreover, one teacher saw the sharing of practices as an opportunity to measure her "personal success against that of team members" in order to improve her own practice.

Participants indicated that their teams provided opportunities for and even invited teachers to share any uncertainties about subject content. This was confirmed by the principal, who regarded "open conversation" as crucial in achieving their team goals. Participants therefore attributed the success of their collaboration to the "very good" communication in teams and the fact that all members were knowledgeable about what to do and what the objectives were. What was required for teachers, however, was to "keep an open head... we are not too old to learn".

What participants valued was the close proximity of the classrooms for the particular grades. This arrangement ensured informal communication "at least twice a day" and allowed teachers to quickly act as "sounding boards" for ideas. Participants indicated that they also used technology, such as e-mail messages, or a "Whatsapp" group to share information on the topics teachers had to teach on particular days. The clear willingness of teachers to share PowerPoint presentations, new books and relevant articles and give advice and assistance to team members was evident from the findings. A teacher in the focus group explained how the introduction of the "new CAPS" (Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement) triggered and almost "compelled" teams to work together. He referred to his experience in Grade 7: "We work very closely because we needed to redo almost everything."

The team approach created an opportunity for teachers to share responsibilities, which in the light of teachers' workload was a "welcome relief". One teacher noted: "We divide the work which lessens our work pressure and provides more time for other responsibilities". According to the principal, the sharing of responsibilities had an even greater impact: "When you share responsibilities, and when you are part of a team where collaboration is present, you take ownership of the process which you are part of." A member in the focus group also explained that teachers took turns to set papers and that this was to the "benefit of learners" who were then "exposed" to other teachers' test papers. However, the idea of a fair distribution of work was emphasised.

Although the findings showed strong evidence of structured formal teams, many participants expressed the need to have "more opportunities to meet formally". Scheduling such opportunities within a school's timetable was an issue, but top management worked on a solution to address this issue in 2015. The principal, however, acknowledged that effective teacher collaboration "will not be a success overnight, and that patience is the key" to making further improvements.

From participants' responses, the emerging notion of professional learning implied joint work and sharing of responsibilities (Forte & Flores, 2014:98) by means of vertical and horizontal structured teams in the form of subject-area and grade-level teams. The study invariably showed that these structures provided the venue for teacher learning through sharing and exchanging new ideas to improve their practice. This concurred with the studies of Blacklock (2009:223, 224), Dadds (2014:10), Forte and Flores (2014:98), Rosnida and Malakolunthu (2013:566) and Poulos et al. (2014:30). The collegial debate that occurred in teams served as a construction of knowledge which was essential for transformative learning (Drago-Severson, 2008:62, 63; Nelson, Deuel, Slavit & Kennedy, 2010:178; Poulos et al., 2014:30; Wells, 2014:493). This is in line with the view of Williams (2010:104), who regards the notion of "pooled intelligence" as a recognised benefit of collaboration. Moreover, participants expressed strong commitment to collaborative learning and willingness to share practices in teams (Drago-Severson, 2007:76; Nelson et al., 2010:176; Greer, 2012:8; Pedder & Opfer, 2011:742). In some cases a triggering event has the potential to enhance transformative learning (Santalucia & Johnson, 2010: CE-3), as the introduction of CAPS showed in the study. When teachers are engaged in collaborative learning they become dependent upon each other and by doing so establish an interdependence among the adults in a school (Williams, 2010:93), as indicated in this study. Although the study revealed a supportive learning environment for teachers' learning, which participants acknowledged and appreciated (Brouwer 2011:107; Greer 2012:8), it had probably not yet been optimised (Mezirow 2000:4), especially considering the desire for more opportunities for interaction and collaboration. Moreover, transformative learning requires ample time for continuous dialogue to ensure its lasting impact on teachers' learning and practice (Williams, 2010:153). Moreover, for the sake of effective transformative learning to occur, it is necessary to provide appropriate opportunities and assist teachers in self-reflection that involves the evaluation and re-evaluation of their beliefs and assumptions regarding teaching and learning (cf Santalucia & Johnson, 2010: CE-4). Examining their beliefs and assumptions is a crucial element of the transformative learning process (cf. Santalucia & Johnson 2010: CE-4).

5.3 Professional relationships: "As a teacher you get the feeling of togetherness"

The participants shared a feeling of "togetherness" which they viewed as being of "inestimable worth". Their sharing of "ideas and ideals" made them feel that they were no longer on "an island". The notion of caring for each other was echoed by many participants. One teacher considered this caring as "unbelievable, not only on school level, but personally too". Another teacher mentioned that teachers would set a test paper if a colleague was not coping personally or professionally. Their appreciation for each other was also expressed in more tangible ways, such as sending "gifts like a coffee sachet or sometimes a red pen before the marking season!" to each other or even writing "a small note saying we are appreciating the job done!"

The idea of "communicating in a respectful manner", respect for each other, listening to the views of others and acknowledging differences of opinion was endorsed by many participants. Participants also acknowledged their personality differences, which were essentially "positive" for their collaboration, but had to be managed correctly to avoid unnecessary conflict. They considered their differences as "complementary" and something which added to the learning experience of members. In this regard the principal said:

Disagreement and differences in opinion are valued. It is listened to, debated and respected. However, if no consensus agreement can be reached, it is paramount that a decision is made, and then everybody - whether you agree or not - have to buy into the decision and follow through upon it.

The principal's view was confirmed by a teacher:

People are entitled to their own opinion, but cannot impose their will on others . They need to talk about the differences and calmly work out a solution that would work for everybody and with which everybody agrees to.

The reasons participants gave for their effective professional relationships varied. References to trust in each other emerged rather strongly. The necessity of trust in professional relationships is also supported by various scholars (Cranston, 2009:10; Forte & Flores, 2014:93; Williams, 2010:99). Other participants referred to the necessity of sharing the same values in their collaboration. Two teachers said that honesty towards team members was very important. One teacher noted: "I prefer when a problem arises that the person will come directly to me to talk about it. There are always two sides to a situation and if I can rectify it, it should be done immediately."

It was clear from the findings that professional relationships played a key role in teachers' learning. Structured teams brought teachers together and assisted them in forming close professional relationships (Forte & Flores, 2014:102; Williams, 2010:100) which broke down the barriers of teacher isolation (Fleming, 2007:23; Gaspar, 2010:122; Pedder & Opfer, n.d.) or individuality. In fact, their individuality contributed to the effective learning of other team members (Fleming, 2007:29). Differences in approach were resolved for the sake of a higher goal (Greer, 2012:73).

Taylor and Cranton (2013:37) refer to the important role that empathy plays in transformative learning, which was also supported in this study. Caring relationships and an ethos of trust existed in this school (Blacklock, 2009:183; Forte & Flores, 2014:93; Smith, 2014:482, 484). Moreover, transformative learning necessitates the existence of a trusting environment in which team members can reflect on their practice, since this in essence reveals adult learning theory in action (Rickey, 2008:37). Another teacher quality that emerged from the study was respect for other team members. The idea that mutual respect built participants' conducive collaborative relationships is supported by various scholars (Cranston, 2009:10; Brouwer, 2011:108; Katz & Earl, 2010:27, 28; Rosnida & Malakolunthu, 2013:561).

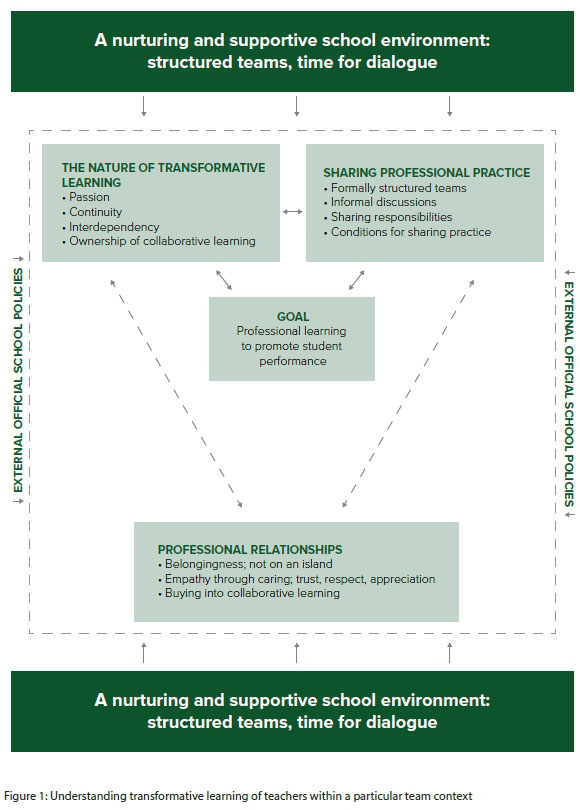

The findings of this study are depicted in Figure 1. The study demonstrates that external official school policies, such as the Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development, can influence transformative learning in schools. A nurturing and supportive school environment in which teams are formally structured and ample time scheduled plays a key role in transformative learning of staff. This study reveals how the three themes, the nature of transformative learning, the sharing of professional practice and the necessity of professional relationships, contribute to transformative learning of staff at a school.

6. Conclusion

This study uncovered the construction of knowledge and skills among a team of Mathematics teachers as a result of collaborative learning. It revealed that participants' orientation to team dynamics and the infrastructures at the school positively impacted on participants' learning and also their desire for more opportunities to learn. Participants' focus on student performance was of the utmost concern and the more developed such collaboration appeared to be, the more positive the link was with the two key measures of learning: professional learning and student performance. The key characteristics that were revealed in the study included collective responsibility for student learning; collaboration which focused on individual and collective professional learning; and empathy aspects such as openness, respect, caring and mutual trust.

Although this study focused on a particular team's learning processes, these processes were embedded in structured teams that played a significant role in shaping teachers' learning. However, the study also showed that the school had previously undergone a cultural shift in which the necessity of teachers' being adult learners was emphasised. It implied that teachers had to become committed to working together and that they had to buy into the notion of teacher learning. Furthermore, it required the active support of school management to establish a school culture that was conducive to teacher learning.

The findings presented in this study have proved to be productive in illuminating issues associated with transformative learning at schools for both practitioners and scholars. Considering the fact that transformative learning in teams is well worth adopting in schools, I recommend that more empirical studies should be done to investigate this theory in development. Different school contexts and structures, such as smaller, disadvantaged or rural schools with other staff and learner configurations, may well add to the body of knowledge needed to create a conducive school environment that will promote the transformative learning of teachers.

8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work is based upon research supported by the National Research Foundation in South Africa

7. References

BRYAN, J. & BATES, A.J. 2015. Creating a constructivist online instructional environment. TechTrends, March/April 2015, 59(2):17-22. [ Links ]

BLACKLOCK, P.J. 2009. The five dimensions of professional learning communities in improving exemplary Texas elementary schools: A descriptive study. University of North Texas, Denton, United States of America). (Doctoral dissertation). [ Links ]

BOTHA, E.M. 2012. Turning the tide: Creating professional learning communities (PLC) to improve teaching and learning in South Africa. Africa Education Review, 9(2):395-411. [ Links ]

BROUWER, P. 2011. Collaboration in teams. University of Utrecht, the Netherlands). (Doctoral thesis). [ Links ]

CHA, Y-K., & HAM, S-H. 2012. Constructivist teaching and intra-school collaboration among teachers in South Korea: An uncertainty management perspective. Asia Pacific Education Review, 13: 635-647. [ Links ]

CRANSTON, J. 2009. Holding the reins of the professional learning community: Eight themes from research on principals' perceptions of professional learning communities. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, February, 90, 1-22. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J.W. 2013. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

DADDS, M. 2014. Continuing professional development: Nurturing the expert within, Professional Development in Education, 40(1):9-16. [ Links ]

DRAGO-SEVERSON, E. 2007. Helping teachers learn: Principals as professional development leaders. Teachers College Record, 109(1):70-125. [ Links ]

DRAGO-SEVERSON, E. 2008. 4 practices serve as pillars for adult learning, Journal of Staff Development, 29(4):60-73. [ Links ]

ENGSTROM, J. & KABES, S. n.d. Learning Communities: An Effective Model for a Master's of Education Program. https://www.smsu.edu/resources/webspaces/campuslife/learningcommunity/ faculty%20publications/learning%20communities%20an%20effective %20model%20for%20a%20masters%20of%20education%20program.pdf. Date of access: 29 Jul 2016. [ Links ]

FEREDAY, J. & MUIR-COCHRANE, E. 2006. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, (5(1):1-11. [ Links ]

FOSNOT, C. T. 2005. Constructivism revisited: Implications and reflections. The Constructivist, Fall, 16(1). http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1035&context=cpe. Date of access: 28 Jul. 2016. [ Links ]

FORTE, A.M., & FLORES M. 2014. Teacher collaboration and professional development in the workplace: A study of Portuguese teachers. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(1): 91-105. [ Links ]

GASPAR, S. 2010. Leadership and the professional learning community. University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE. (Doctoral thesis. [ Links ])

GAU, W-B. 2014. A mutual engagement in communities of practice. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116:448-452. [ Links ]

GEMEDA, F.T., FIORUCCI, M., & CATARCI, M. 2014. Teachers' professional development in schools: Rhetoric versus reality. Professional Development in Education, 40(1):71-88. [ Links ]

GREER, J.A. 2012. Professional learning and collaboration. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. (Doctoral dissertation. [ Links ])

JOHNSON, L.R., STRIBLING, C., ALMBURG, A., & VITALE, G. 2015. "Turning the sugar": Adult learning and cultural repertoires of practice in a Puerto Rican community. Adult Education Quarterly, 65(1):3-18. [ Links ]

KATZ, S., & EARL, L. 2010. Learning about networked learning communities. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 21(1):27-51. [ Links ]

KNOWLES, M.S. & ASSOCIATES. 1986. Andragogy in action: Applying modern principles of adult education. Canadian Journal of Communication, 12(1):77-80. [ Links ]

LIU, C.H. & MATTHEWS, R. 2005. Vygotsky's philosophy: Constructivism and its criticisms examined. International Education Journal, 2005, 6(3): 386-399. [ Links ]

MATAMALA, S.L. (2013). Professional learning experiences in student learning as a vehicle for transformational learning. University of La Verne, La Verne, California. (Doctoral dissertation). [ Links ]

MERRIAM, S.B. 2001. New directions for adult and continuing education 89. http://umsl.edu/~wilmarthp/modla-links-2011/Merriam_pillars%20of%20anrdagogy.pdf. Date of access: 2 Feb. 2015. [ Links ]

MEZIROW, J. 1991. Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

MEZIROW, J. 2000. Learning to think like an adult: Core concepts of transformation theory. (In J. Mezirow & Associates, eds. Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. p. 3-33. [ Links ])

MEZIROW, J. 2003. Epistemology of transformative learning. https://www.google.co.za/?gws_rd=ssl#q=epistemology+of +transformative+learning+jack+mezirow. Date of access: 15 Feb. 2015. [ Links ]

MOCKLER, N. & NORMANTSHURST, L. 2004. Transforming teachers: New professional learning and transformative teacher professionalism. (Paper presented to the Australian Association for Educational Research Conference, University of Melbourne). [ Links ]

NEWMAN, M. 2014. Transformative learning: Mutinous thoughts revisited. Adult Educational Quarterly, 64(4):345-355. [ Links ]

NELSON, T.H., DEUEL, A., SLAVIT, D., & KENNEDY, A. 2010. Leading deep conversations in collaborative inquiry groups. The Clearing House, 83:175-179. [ Links ]

NIGHTINGALE, D.J. & J CROMBY, J. 2002. Social Constructionism as Ontology Exposition and Example. Theory & Psychology, 12(5): 701-713 [ Links ]

NOHL, A-M. 2015. Typical phases of transformative learning: A practice-based model. Adult Education Quarterly, 65(1):35-49. [ Links ]

ONWUEGBUZIE, A.J., LEECH, N.L., & COLLINS, K.M.T. (2012). Qualitative analysis techniques for the review of the literature. The Qualitative Report, 17:1-28. [ Links ]

PEDDER, D. & OPFER, V.D. 2011. Are we realising the full potential of teachers' professional learning in schools in England? Policy issues and recommendations from a national study. Professional Development in Education, November, 37(5):741-758. [ Links ]

POULOS, J., CULBERSTON, N., PIAZZA, P., & D'ENTREMONT, C. 2014. Making space: The value of teacher collaboration. Education Digest, 80(2):28-31. [ Links ]

RICKEY, D.L. 2008. Leading adults through change: An action research study of the use of adult and transformational learning theory to guide professional development for teachers. Capella University, Minneapolis, Minnesota. (Doctoral Dissertation). [ Links ]

ROSNIDA, A., & MALAKOLUNTHU, S. 2013. Teacher collaborative inquiry as a professional development intervention: Benefits and challenges. Asia Pacific Education Review, 14:559-568. [ Links ]

SANTALUCIA S., & JOHNSON, C.R. 2010. Transformative learning: Facilitating growth and change through fieldwork. Linking Research, Education & Practice, October, CE1-CE8. http://moodle.chatham.edu/pluginfile.php/33141/mod_resource/content/1/ Transformative_Learning.pdf. Date of access 15 Aug 2014. [ Links ]

SMITH, G. 2014. An innovative model of professional development to enhance the teaching and learning of primary science in Irish schools. Professional Development in Education, 40(3):467-487. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2011. Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and development in South Africa (2011-2025). Pretoria: Department of Basic Education and Department of Higher Education and Training. http://getideas.org/resource/integrated-strategic-planning-framework-teacher-education-and-development-south-af/ Date of access: 12 Aug, 2014. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2015. South Africa's 4+1 plan to boost maths teachers http://www.southafrica.info/about/education/education-230315.htm#.VRpCdPmUeSo. Date of access: 30 Mar. 2015. [ Links ]

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA. 2014. Department Basic Education. Report on the Annual National Assessment of 2014, Grades 1 to 6 & 9. http://www.saqa.org.za/docs/rep_annual/2014/REPORT%20ON%20T HE%20ANA%20OF%202014.pdf. Date of access: 9 Apr. 2015. [ Links ]

ROUT, S. & BEHERA, S.K. 2014. Constructivist approach in teacher professional development: An overview. American Journal of Educational Research, 2(12A): 8-12. [ Links ]

STEYN, G.M. 2013. Principal succession: The socialisation of a primary school principal in South Africa, Koers: Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, 78(1):45-53. [ Links ]

STEYN, G.M. 2014a. Teachers' perceptions of staff collaboration in South African inviting schools: A case study. Pensée Multidisciplinary Journal, 75(5):216-229. [ Links ]

STEYN, G.M. 2014b. Exploring the status of a professional learning community in a South African primary school. Pensée Multidisciplinary Journal, 76(5):256-269. [ Links ]

STEYN, G.M. 2015. Creating a teacher collaborative practice in a South African primary school: The role of the principal. The Journal of Asian and African Studies, 50(2):160 -175 [ Links ]

TAYLOR, E.W. 2007. An update of transformational learning theory: A critical review of the empirical research (1999-2005). International Journal of Lifelong Education, 26:173-191. [ Links ]

TAYLOR, E.W. & CRANTON, P. 2013. A theory in progress: Issues in transformative learning theory. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 4(1):33-47. [ Links ]

Valdmann, A. Rannikmae, M. & Holbrook J. 2016. The effectiveness of a CPD programme for enhancing science teachers' self-efficacy towards motivational context-based teaching. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 15(3): 284-298. [ Links ]

WATSON, C. 2014. Effective professional learning communities? The possibilities for teachers as agents of change in schools. British Educational Research Journal, 40(1):18-29. [ Links ]

WELLS, M. 2014. Elements of effective and sustainable professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 40(3):488-504. [ Links ]

WILLIAMS, M.L. 2010. Teacher collaboration as professional development in a large, suburban high school. University of Nebraska: Lincoln, Omaha. (Ph D thesis). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

G.M. Steyn

Department of Educational Leadership and Management

University of South Africa

P O Box 392, Pretoria, 0003

steyngm1@unisa.ac.za

Published: 03 Mar. 2017