Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Koers

versão On-line ISSN 2304-8557

versão impressa ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.81 no.2 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.81.2.2262

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Christian philosophy of education in South Africa: the cultural-historical activity theory to the rescue?

J L van der Walt

Faculty of Education, Northwest University, Mafikeng Campus, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Parents' choice of schools for their children has become particularly problematic in the current circumstances because of the fact that most schools have become secular and hence cannot support Christian parents in their task of educating children in line with the former's baptismal vow. In addition to this, Philosophy of Education has all but disappeared from teacher education curricula. These circumstances have not, however, detracted from Christian parents', teachers', caregivers' and other educators' need for a Christian Philosophy of Education. This article offers such a Philosophy of Education in the form of Biblical perspectives regarding the main facets of education couched in cultural-historical activity theory. This approach circumvents objections against a mere "grab bag" of Biblical perspectives about education as well as against yet another master theory or grand narrative about Christian education.

Keywords: education, Christian education, philosophy of education, Christian philosophy of education, Biblical perspectives, cultural-historical activity theory

ABSTRAKTE

Ouers se skoolkeuse het in die huidige omstandighede tot 'n ernstige probleem ontwikkel aangesien die meeste skole gesekulariseerd geraak het en dus nie die ouers kan ondersteun in hulle taak om die kinders ooreenkomstig die ouers se doopbeloftes op te voed nie. Om die probleem te vererger, het Filosofie van die Opvoeding ook uit die kurrikulums vir onderwysersopleiding verdwyn ten gunste van 'n blote teoretiese refleksie oor onderwys en opvoeding. Christenouers, -onderwysers, -sorggewers en ander -opvoeders het desondanks nog steeds 'n behoefte aan 'n Bybelsgefundeerde Filosofie van die Opvoeding. Hierdie artikel omlyn sodanige Filosofie van die Opvoeding. Dit benut die kultuur-historiese aktiwiteitsteorie as 'n raamwerk vir 'n stel Bybelse opvoedingsperspektiewe. Hierdie benadering voorkom enersyds besware teen 'n blote onsamehangende versameling Bybelse perspektiewe oor opvoeding en onderwys en andersyds besware teen die bou van 'n nuwe meesterteorie of grootskaalse narratief aangaande Christelike opvoeding.

Sleutelterme: opvoeding, onderwys, Christelike opvoeding, Christelike onderwys, filosofie van die opvoeding, Christelike opvoedingsfilosofie, Bybelperspektiewe, kultuur-historiese aktiwiteitsteorie

1. INTRODUCTION

There are around 2.2 billion Christians around the world, which represents approximately 31 per cent of the world population (Pew Research Forum, 2015). It can be assumed that in most cases where Christians have not become secularised to the point of only paying lip service to their religion, they would take the Shema Yisrael seriously: "Hear O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength. These commandments that I give you today are to be upon your hearts. Impress them on your children. Talk about them when you sit at home and when you walk along the road, when you lie down and when you get up. Tie them as symbols on your hands and bind them on your foreheads. Write them on the doorframes of your houses and on your gates" (NIV-Deuteronomy 6: 4-9). Christian parents who take this call seriously baptize their children in the presence of their church community, and vow as follows regarding the upbringing of the children: "Do you promise to instruct this child by word and example, with the help of the Christian community, in the truth of God's Word, and in the way of salvation through Jesus Christ? Do you promise to pray for them and teach them to pray? Do you promise to nurture them within the body of believers, as citizens of Christ's kingdom?" (Christian Reformed Church, 1991/1994).

The congregation is then invoked to assist and support the parents in the nurture and training of the child. In the covenant, the entire Christian community takes responsibility for the training up of covenant children in the faith. What this has historically meant is the Christian instinct to start schools, says Sumptner (2010). The choice of the school in which parents place their child at around age six depends on how the parents see their duty to have the child instructed in terms of the covenantal vow. According to experts in the field, parents have three options in this regard.

The first option is to educate the child into their specific religion and its specific faith tradition, in this case, the Christian religion. The purpose of this approach is to promote the child's personal, moral and spiritual development as well as to build his or her religious identity with a particular religious tradition. This is a confessional approach that emphasises education in exclusively Christianity, teaching children to live in accordance with the specific religious tenets of the Christian religious tradition (Xiao, 2015). Christian parents who take their covenantal vows seriously will arguably prefer this option.

The second option is to educate the child about religion, in other words guide the child to gain knowledge about various religions without preference for any specific religion. This approach entails a more or less academic examination of various religious traditions. It contextualises religion with a comparative study of religions, their history and sociology (Xiao, 2015).

The third option is to educate the child to learn from religion, in other words to give the child the opportunity to consider different answers to various religious and moral issues in order to help him or her to develop their own views about religious and moral issues in a reflective way (Schreiner, 2005: 1). Religious education in the context of citizenship education is a typical example of this approach. This approach entails active learning and inclusive interactivity with other religions; it is value-based and process-led, and allows the children (pupils, students, learners) to develop and articulate for themselves their own religious views and engage in debate with others about their views. They engage with their own religious context via encounter and dialogue with other religions (Miedema & Ter Avest, 2011: 412). This approach takes the personal experience of the pupil as its point of departure. The idea is to enhance the student's capacity to reflect upon important questions of life and to provide an opportunity to develop personal responses to major moral and religious problems (Xiao, 2015).

The significance of these choices confronting parents and other educators such as caregivers, teachers and pastors, in view of the theme of this article, lies in the fact that the school choice that parents make will depend largely on their general view of education, their "philosophy" of education. Put differently, their choice will depend on what they see as the aim of education, the methods to be employed to achieve that aim, the learning contents, how discipline has to be inculcated and maintained, to mention only a few aspects of what parents have to be clear about in their minds. Significant is also how parents see the connection between the duties of the parental home and those of the school. Do they view the school as an extension of the parental home (viewing the teachers as in loco parentis, i.e. in the place of the parents as extensions of the parents) or do they regard the school as a separate and independent societal relationship that enters into a partnership with parents and the church? Will a state school, which tends to function on the secular (supposedly non-religious, non-faith, non-ecclesiastical) principles embodied in the last two options mentioned above, be able to enter into a fruitful partnership with parents who have made the covenantal vow? Or should the children be placed in a private / independent school that functions on exactly the same covenantal principles as those of the parents? All these are educational-philosophical issues that parents have to resolve before placing their child in a school.

To be able to make choices in this regard, parents as well as the church leadership and Christian schools and teachers (including those teaching in secular surroundings such as state schools) need guidance in the shape of a Christian philosophy of education.

2. THE PROBLEM

Philosophy of Education as a scholarly discipline only came to a modest level of maturity in the Afrikaans community in South Africa in the form of publications by J Chr. Coetzee (in the Christian reformed tradition) and C K Oberholzer (in the phenomenological tradition). Coetzee's reformed-Christian approach is evident in his work (cf. his Christian National Education (1968) and Introduction to a General Theory of Education (1973); titles translated from the original Afrikaans). Oberholzer, on the other hand, while also coming from a Christian background, preferred to expound his philosophical views of education in phenomenological terms in books published in approximately the same time-frame as those of Coetzee (Introduction to Principled Pedagogics (1954) and Prolegomena of Principled Pedagogics (1968); both titles translated from the original Afrikaans).

English-speaking philosophers of education in South Africa had by that time already had the advantage of a long tradition of Philosophy of Education that hailed as far back as the ideas of Locke, Hume, Russell, Bentham and many other British philosophers as well as those of American philosophers such as Dewey, James, Peirce and Whitehead, to mention only a few. The approach of most of these South African philosophers was not explicitly Christian but rather more pragmatic, critical-emancipatory, rationalistic, positivistic and / or linguistic-analytical in nature. English-speaking South African educators and educationists who interested themselves in an explicit Christian philosophy of education consult(ed) the works of Jay Adams, Ted Tripp and others to whom reference is made below.

Several developments in the realm of an explicit Christian-reformed Philosophy of Education followed after the seminal work done by Coetzee. Many Christian educators (parents, teachers, caregivers, pastors) and educationists consulted, and are still consulting, the publications of pastoral theologians such as Adams, Tripp, Henry Cloud, John Townsend, George Boyd, Larry Crabb, Emerson Eggeriches, Martyn Lloyd-Jones, John MacArthur, Josh McDowell, Wayne Mack and others, despite the fact that these authors were / are theologians and / or pastoral counsellors and not professional educationists. They found / find the guidance of these theologians useful in that the latter derive(d) their pedagogical insights directly from the Bible and made them accessible to people engaged in the process of guiding other people, including children, towards (greater) maturity. Others, however, found the work of, for instance, Stuart Fowler, Harro van Brummelen, Richard Edlin, John van Dyk, Doug Blomberg, Geraldine Steensma, Gloria Stronks and others more suitable as guiding lights as they seem(ed) to be more pedagogically oriented. The recent work of J L van der Walt and A de Muynck (The Call to Know the World, 2006) followed the same orientation.

A new tendency arose in Afrikaans educational circles by the mid-1970s when scholars such as P G Schoeman (Grondslae en Implikasies van 'n Christelike Opvoedingsfilosofie, 1975; Aspekte van die Wysgerige Pedagogiek, 1979; Introduction to Philosophy of Education, 1980; Wysgerige Pedagogiek, 1983; Historical and Fundamental Education, 1985), J H van Wijk (who by the time of his early death had only published a number of brief monographs), J L van der Walt and others (Fundamentele Opvoedkunde vir Onderwysstudente, 1982; Die opvoedingsgebeure: 'n Skrifmatige perspektief, 1982 with E I Dekker and I D van der Walt; Oor opvoeding in 'n neutedop, 1983) began constructing a reformed Philosophy of Education based on the tenets of the Philosophy of the Cosmonomic Idea. In hindsight, this project can be seen as an effort to create a "grand pedagogical narrative." By the early 1990s, this approach became unpopular, however, which explains why, after the retirement of (and the death of Van Wijk) these "grand narrative" philosophers of education the project petered out. The departure from the "grand narrative" approach was reinforced, as will be explained below, by a confluence of factors resulting in the disappearance of Philosophy of Education from teacher education curricula in post-1994 South Africa.

The postmodern spirit of the late 1980s worked hand in hand with the teacher education policy changes that were introduced in South Africa after the first democratic elections that led to a regime change in 1994. The new official approach to teacher education can arguably be partly ascribed to the general muting of critical scholarship in the humanities and social sciences in the post-1994 South Africa (Weeks, Herman, Maarman & Wolhuter, 2006; Gumede & Dikeni, 2009). The humanities, including the practice of Philosophy of Education, in South Africa seemed to have suffered the same fate as in other parts of the world. The neo-liberal economic revolution driven by utilitarian and pragmatic principles such as performativity and profit-making also penetrated into the higher education sphere, including teacher education (see Maistry (2014) for a detailed discussion). This tendency, coupled with a new approach to teacher education from 2000 onwards, led to the demise of Philosophy of Education as an academic subject to be mastered by future teachers. This, coupled with the already mentioned postmodern aversion to the "grand narrative approach" to Philosophy of Education, resulted in the demise of once strong and vibrant Philosophy of Education departments at universities. In several cases, the subject of Philosophy of Education was watered down and offered to the students in the contexts of new subject domains such as Life Skills, Social Studies, Life Orientation and Religion Studies.

An example drawn from official policy regarding teacher education in South Africa will illustrate this point. The Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development in South Africa 2011-2015 (South Africa, 2011) mentions as one of the competences that a teacher should possess (Appendix C) that a teacher should "be able to reflect critically on own practice, in theoretically informed ways and in conjunction with their professional community of colleagues to constantly improve and adapt to evolving circumstances". The document stops at "theoretically informed ways" and does not go on to "philosophically informed ways". This is indicative of a lacuna in the education of future teachers in South Africa. As Strauss (2009:59) pointed out, special scientists (in this case, educationists and hence their students) have two options:

(i) Either they give account of the philosophical presuppositions with which they work - in which case they operate with a philosophical view of reality, or they

(ii) Implicitly (and uncritically) proceed from one or another philosophical view of reality - in which case they are the victims of a philosophical view.

There is a long-standing tendency among scholars, particularly those working in a positivistic paradigm, to circumvent the necessity of dealing with the philosophical foundations of their subject. All theories, including those encapsulated in the phrase "theoretically informed ways", are however inadvertently and unavoidably rooted in pre-theoretical (philosophical) foundations. This has to be recognised also in the education of future teachers (cf. Coletto, 2008: 461). There seems to be consensus among philosophers and methodologists that foundational (philosophical) issues merit attention when studying a subject or preparing for a future career, for instance as a teacher. Coletto (2009: 294-298) underscores the importance of studying worldview ideas, basic patterns of thought that shape reflection, basic motives flowing from a person's worldview, the role of faith, worldview and religion. Merriam (2009: 8) concurs: it is important for a scholar, and by extension a teacher, to be informed about the philosophical foundations of pedagogics as a scholarly subject. These foundations go by a variety of nomenclature: traditions, theoretical underpinnings, theoretical traditions and orientations, theoretical paradigms, worldviews, epistemologies and theoretical perspectives. Whatever the name, each person should make sense of the underlying (transcendental) philosophical influences in education in his or her own way.

Whereas the Departments of Basic and of Higher Education and Training seem to be satisfied with teacher education to the level of being theoretically informed about the intricacies of the teaching profession, scholarly insight leads one to insist on teacher education at the deeper level of understanding the underlying philosophical foundations and roots of teaching and education. To do so can only be effected through the reintroduction of Philosophy of Education as a guiding light for all educators, particularly as part of teacher education programmes, and for parents. The need to reinstate a Christian Philosophy of Education in particular in South Africa is supported by the fact that around 78 per cent of the South African population still adhere to the Christian religion (according to the last official census held in South Africa, in 2001 (Media Club South Africa, Fast Facts, 2016)). Ways and means have therefore to be found to bring a Christian Philosophy of Education to life again so that it can once more serve as a guiding light for teachers and other educators (parents and caregivers) when engaging in the education of upcoming generations. Teachers' and schools' philosophy of education forms an important guideline for parents when considering their options about where to place their child for post-parental-home education.

3. THE SEARCH FOR A GUIDING THEORY

If parents, teachers, pastors and teacher educators possessed a "God's eye view" of what education is and should normatively entail, they would have had no need for theory about education. However, due to the fall into sin, no educator possesses such knowledge, and hence has to resort to other means to understand and explain the pedagogical situation as a reality. As mentioned above, there was a time in South African history of (teacher) education that Christian philosophers of education sought refuge in the construction of grand theories of education, i.e. theories that could explain in detail what education entails and in fact should (normatively) entail. As also indicated, the current postmodern and post-post-modern zeitgeist is not amenable to such an approach anymore, as Olthuis (2012) and Van der Walt (2015) have convincingly argued.

While a grand narrative approach to the understanding and explanation of education is not desirable anymore, the converse is also valid. Students of (Christian) education will in all probability have little use for lists of Biblical text selections under the headings of (for instance) "the educator", "discipline", "learning contents", "curriculum" and so on. Such a "grab bag" of Biblical verses and perspectives will arguably not guide them satisfactorily to understand the intricacies of (Christian) education (including teaching and learning).

A third approach is indicated, one that on the one hand possesses the power of a systematic theory while on the other hand cannot be construed as a "grand narrative" that attempts to explain in the finest detail education as a phenomenon and a process, thereby acting as a virtual cookie cutter for educational practice (marked by sameness and a lack of originality; mass-produced). The value of a theory, as Halverson (2002: 244-5) correctly argued, lies in how well it can shape an object of study by highlighting the relevant issues; in other words, how well the theory can serve as a classification scheme in that it provides relevant insights into the object that it is applied to. A relevant theory has the ability to bring certain aspects regarding education into focus while it allows less relevant aspects to fade into obscurity. In view of this, an appropriate theory possesses at least the following four characteristics. It firstly possesses descriptive power in that it helps us make sense of and describe education as a phenomenon or process. Second, it possesses rhetorical power in that it helps us talk about education, provides a conceptual structure and serves as a map of the education world. Third, it possesses inferential power: it helps us make inferences about education and shows us where to look for relevant information. Finally, it possesses application power: it helps us apply our knowledge about education in the real world, among others for pragmatic reasons. A theory that complies with these four requirements is capable of gathering together all the isolated bits of data about Christian education into a coherent conceptual framework of wider applicability (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2011: 9).

The search for a theory that complies with all these requirements has unearthed a theory known as the cultural-historical activity theory (the CHAT). Analysis of this theory reveals that although it was first conceived in Russia in the period around the 1917 Revolution by Lev Vygotsky and further developed by theorists such as Leonti'ev and Engeström (Asghar, 2013: 19-22; Stetsenko & Arievitch, 2004: 476; Yamagata-Lynch, 2010: 13, 25-26; Postholm, 2015: 43), it seems to dovetail in several respects with the work of Talcott Parsons in the West (Parsons, 1973; 1990; 1996). For purposes of this article, as Wilson, Cole, Nixon, Nocon, Gordon, Jackson, Garia and Minami (2013: 1) advised, "the differing formulations [of the CHAT could be seen] as expressions of a single family of theoretical commitments". Examination of the CHAT shows that Yamagata-Lynch (2010: 24) is correct in concluding that the CHAT could serve as a framework to help identify the boundaries of a complex system such as embodied in the term "Christian education" (cf. White, 2012: 14).

There is, however, the problem of syncretism and/or synthesis to overcome, i.e. the dangers of attempting to merge the tenets of a secular theory such as the CHAT with those of a radical Biblical approach to education:

The issue at hand is this: any method of teaching ... that is not saturated with, limited by, and resting upon the explicit Word of God, has no right to call itself Christian or Biblical. Moreover, any method of teaching . that derives its definition of our problems from humanistic presuppositions, which ignore, compromise, alter or downplay the clear teachings of Scripture, and uses methods of treatment based upon such presuppositions must be regarded as nonchristian, extrabiblical, and unscriptural (Owen, 2003: 8-9).

A way has been found out of this predicament, however. In the first place, it was argued that the exponents of the CHAT came to the formulation of their theory on the basis of their particular and unique examination of reality, a reality created and sustained by the God of the Bible. While their examination did not yield results that are in all respects Biblical, such as its bias towards the social, cultural and historical aspects of reality, this can be counterbalanced with a Biblical view of reality. Second, CHAT tenets and the presuppositions in which they are rooted have been found to be rarely in conflict with Biblical views. This will become clear in the discussion below where CHAT views are employed in the context of a Biblical view of reality and of education. Third, Christian thinkers are compelled in terms of 2 Corinthians 10:5 to "take captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ" (New International Version). This "making obedient" of the secular thoughts encapsulated in the CHAT entails a process of life-view and / or philosophical and / or religious transformation, as Klapwijk (1989: 48) argued: Christian philosophy (of education) often finds itself challenged by ideas that are in themselves not strictly Biblical in origin, meaning or impact. When this occurs, Christian philosophy (of education) is called to take a critical stance regarding such cultural goods and societal achievements. Within the all-encompassing framework of a secular worldview, these achievements are often objectionable, or at least ambiguous. In spite of these difficulties, however, the "praxis" of the modern secular world still lends itself to reevaluation and reintegration within the Christian "vision for life." This process of "philosophical transformation" is key to making secular thoughts obedient to the cause of Christ, and hence also to that of a Christian philosophy of education. The Bible, as inscripturated Word of God, is instrumental in this process (2 Tim 3: 16).

As will be indicated in the next section, the basic contours of the CHAT can be used for purposes of expounding a Christian approach to education. Key aspects of the CHAT will be explained in Biblical terms in an effort to allow a Christian approach to education to unfold.

4. THE CULTURAL-HISTORICAL ACTIVITY THEORY AS VEHICLE FOR EXPOUNDING A CHRISTIAN/BIBLICAL PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION

The scope of a journal article imposes two constraints on the discussion: it does not allow for a detailed discussion and evaluation of the cultural-historical activity theory (the CHAT) as such; neither does it allow a detailed exposition of a Christian Philosophy of Education. This article should therefore be seen as a first step of a work in progress. The following outline will nevertheless provide grounds for judging whether the CHAT could be regarded as a suitable vehicle for expounding a Christian Philosophy of Education.

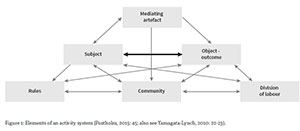

"Activity" forms the unit of analysis in the CHAT. All human activities and actions, hence also educational activities and interactions (including teaching and learning) are seen as activity systems. An activity is a socially constructed and culturally mediated event, procedure or human action (Lampert-Shepel, 2008: 214). This process is also known as positivisation, i.e. the act of giving shape (positivizing) already existing (creational) principles. This process is graphically demonstrated in the following figure:

The educator is the "subject", the person who engages pedagogically with a person in need of guidance (e.g. a child - the educand). The educator's activity system (pedagogical engagement) and that of the person with whom the engagement takes place are both enabled and constrained by unique contextual conditions (indicated by the arrows), such as their historical situation and environment, on the one hand, and by individual forces and facts (for instance, birth, sex, temperament), on the other. The educator (parent, teacher, pastor, as the case may be) is called to equip, guide, disciple, shape the educand entrusted to his or her care (Deut 6:4-9). The Bible abounds with perspectives about this role and function of educators: They have to set a Godly example for the children to follow (1 Tim 4: 12; 1 Pet 5:2-4; Mat 5: 19), should never put a stumbling block in the child's way (Rom 14:13), should display a giving and generous attitude to others, including the child (Mat 24: 34-36); should as educators emulate the example set by Christ (1 John 2: 6; 13:2-11, Rom 15:1-3; Eph 5:1-2; 1 Cor 11:1; John 15:9-11; 1 John, 3:2-3); love the children deeply (1 Pet 1:22) and serve them in love (1 Pet 4:9-10; Rom 12:9-10;Tit 3:14; 1 Cor 12:1-31); teach them to be obedient (John 14:15; Prov 13:13; 1 John 5:2-3; 1 John 2:3-6; 2 John 6; Isa 48:17-19; Gal 5:13); to love their enemies and do good to them (Mat 5:43-47; Rom 12:20), to turn the other cheek (Mat 5: 38-42); to withstand and overcome sin (2 Cor 5:17; Ezek 36:25-27); be peacemakers (Mat 5:9); depend on the Lord (1 Pet 5:6-7); grow in faith and godliness (2 Pet 3:18); educators have to lead and guide the child to Christ (2 Cor 5:15), teach children not to be self-centred 1 Cor 13:5), to be in self-control and apply self-discipline (Prov 15:28; Gal 5:22-23). Educators should furthermore understand that they have to rear the children in a God-centred way.

The object or outcome (see Figure 1) of the pedagogical engagement is clear: to prepare the child for the love and service of God and fellow-men and to be ready for all good works (The Great Commission and the Cultural Commission; also 2 Tim 3: 16; cf. Colson, 2001: 12). The primary objective of the guiding of the child must be that the latter knows, believes in, loves, reveres and serves the Lord (Deut 6:6-7; Prov 4:23; Prov 29:17; Prov 22:6); to be a happy person (Eccles 11:9-10) and to listen to parental instruction for his or her own good (Prov 1:8-9; 4:1-4; 6:20-24).

Although one has to disagree from a Biblical point of view with Stetsenko and Arievitch (2004: 485-486) when they claim that activities (i.e. actions, deeds, acts) form "the principal foundation of human life... (that) ultimately drives the development of human subjectivity, including the self and the mind, in unique constellations for each individual human being and group," it can be agreed that the educator is always also embedded in a sociocultural-historical world because he or she is formed from within, out of, and driven by the logic of evolving activity that connects individuals in the world, to other people and to themselves. Put differently, the educator's engagement with the educand is always socially, culturally, historically and otherwise contextualised. Contexts such as the following call for planned action on the part of the educator: the educand might occasionally experience affliction and trials (1 Pet 1:6-7; John 9:1-3; James 1:2-4; Ps 119: 67-68; Heb 12:5-11); be led astray through alcohol and drug abuse (1 Cor 6:19-20; Luke 21:34; 1 Cor 5:11), and hence experience anger (James 1: 19-20), a lack of self-control (Prov 25:28), bitterness, resentment and hate (Eph 4: 31-32), speak out of turn (James 3:1-3); suffer from a guilty conscience (1 Pet 3: 15-16); experience a fear of death (Ps 23:4) and / or suffer from depression (Ps 42: 5-6).

The self of the educator as subject is a force that plays an active role in all the processes of education as activity system. Although he or she is partly the result of external social and cultural forces, they are also active agents who contribute to life in their own ways. Educators are what they make of themselves by appropriating culture, thereby making it part of their human functioning and instrument for future pedagogical engagement (Stetsenko & Arievitch, 2004: 489). Children and young people depend on the guidance and nurturing of more mature people to become what they should and wish to become, and the latter are called to attend to the needs of the child (Deut 6:6-7; Ps 51:5; Prov 4:23, Prov 1:8-9; Prov 22:6). The educand has to be guided and nurtured to appropriate more than just his or her material history and culture. Reality and the human condition consist of more than just these aspects, however; the educand has to be "unlocked" in terms of all their human functions, including their religion, faith, ethical orientation and view of justice, ability to live and work wisely and frugally, ability to interact with other persons, to be in command of their feelings and emotions and to conduct a sensible physical existence (Strauss, 2014: 30).

The concept of "mediated action," "cultural mediation" or "mediating artefact," another key aspect of the CHAT (the apex of Figure 1), also reflects the fact that an individual's mental activity is integrated in a social, cultural, educational and historical context. All educators employ cultural artefacts such as language and signs as aids in attempting to attain pedagogical goals (Postholm, 2015: 45). The term "mediated action" is synonymous with "agent-acting-with-mediational-means" (Lampert-Shepel, 2008: 214-215). The Bible mentions, for instance, the following mediated actions that the educator could consider: chastisement (1 Pet 1: 6-7; John 9:1-3), comfort (Ps 23; 91:1-2), communication (Eph 4:15; 4:29; James 1:19), discipline (Heb 12:5-6), giving (2 Cor 8:1-9), imitating Jesus (Rom 8:29-30), loving and serving others (1 John 4: 9-21), obedience (John 15: 10-17), prayer (Mat 6:9-13), trust (Ps 27:13-14), work (1 Cor 10:31; Col 3:17) and setting a good example (Deut 6:4-6).

Actions exist in relation to the context that is indicated by the triangles near the nadir of the activity system (Figure 1). "Rules", "community" and "division of labour" lay the premises and also possible restrictions for the educator's goal-directed actions (Postholm, 2015: 45). Through the educator's participation in the activities of the community or society, i.e. a collective characterised by co-ordinational, communal and collective relationships, the educand begins to understand the rules of acceptable behaviour within the community (such as a school, church community or civil society), and how the various tasks have to be performed in that particular community. As Stetsenko and Arievitch (2004: 479) concluded, the educand then begins to understand him- or herself as situated in clearly defined patterns of social practice. Social rules govern the interactions among the members of a community, and division of labour organises the division of tasks among the members of the community (Asghar, 2013: 21). Rules include the norms and conventions that direct the actions in the activity system. The implication of this is clear in the context of a Biblical approach to education: the educand should be guided and nurtured to have an understanding of his or her respective roles in the church, the school, the family, the state and in civil society, to have a command of the rules governing behaviour in the church and in other societal relationships as well as of the division of labour in the church and in other relationships (cf. Rom 12: 4-8; Eph 2:19-22; 4:11-13; 1 Cor 12:12-31).

The element "community" (societal and social form of life) refers to all people that share the same goals, for instance a church or a school community. This element in figure 1 suggests that the child is shaped by social (and other) factors such as interactive experiences with significant others (parents, church educators, teachers) and group membership (e.g. the peer group) along with the roles that each performs and the positions that they occupy in the church and in other relationships. Individual and social dimensions evolve together in the social development of the individual; there is continuity and reciprocity between individuals and society (their church community, for example). The individual develops in a process of on-going social (and other) transactions and dynamic processes. In this process, he or she develops a relational character through participation in the community, despite the shifting and moving patterns of participation (Stetsenko & Arievitch, 2004:478-479). In the CHAT - and in this is it dovetails with a Biblical anthropology - the educand is not reified as fixed, predetermined and independent of educational and other social processes during its upbringing: s/he belongs first to God and is his gift to the parents (Ps 127: 3-5); s/he possesses God-given potential, and God requires that parents and other educators rear them in a God-centred and -honouring manner. The primary objective of child rearing and nurturing is that the child shall know, believe in, love, revere and serve the Lord (Deut 6:6-7; John 17: 3; Eph 6: 4). Educators must shepherd the child's heart, and not only attempt to correct outward behaviour (Prov 4: 23), and also give instruction to the child, not just lay down rules and expectations (Prov 1:8-9). The Holy Spirit works through the Word of God to develop spiritual growth and change in the life of the child (John 17:17).

5. DISCUSSION AND EVALUATION

While many of the aspects of a philosophy of education derived from the CHAT may be regarded as acceptable in Scriptural perspective, they have - as mentioned - to be augmented and corrected with perspectives flowing from a Biblical understanding of reality. For instance, the reality for which a child has to be brought up consists of more than just a socio-historical-cultural setting. The heavy emphasis in the CHAT on these aspects of reality, even to the extent that religion is regarded as an aspect of reality, has to be counterbalanced by a view of reality that reflects also its faith, ethical, juridical, economic, psychological and physical aspects. The same applies for the educator and the educand; they are more than socio-cultural-historical beings. The human being is above all a religious being, and has to be treated as such. Another shortcoming of the CHAT is that it is silent about forming a child's life view or life concept, particularly his or her relation with the triune God of the Bible.

The CHAT nevertheless offers a useful framework for understanding the tensions that not only exist within an activity system such as education, but also those existing among widely different activity systems, such as the parental home, the school, the state and the church. Knowing the source of tension is important as it necessitates arrangements to harmonise the different interests at stake. The CHAT helps to surface the systemic tensions (Asghar, 2013: 21-22) surrounding the guidance and nurturing of children (and other educands) and inspires all involved in the pedagogical activity to make arrangements for alleviating the tensions. In a way, this viewpoint of the CHAT reflects the twin principles of sovereignty and universality (also referred to as enkaptic interwovenness) in own sphere that societal relationships are expected to adhere to.

It is furthermore clear from Figure 1 that in the context of the CHAT an activity system (in this case, education) is a unified system constitutive of human social life, interpenetrating and influencing all parts of it and never becoming detached or independent of other parts of the system. It is an integrated and interrelated system. As Stetsenko and Arievitch (2004: 490) concluded: human subjectivity (educators), social relations (with the educand) and material practice (education) all have the same ontological grounding. Education as an activity system is not just a matter of simple change, organic growth or maturation, a collection of quantitative changes. Its evolvement is a complex process of qualitative changes and reorganisation. The development of subjectivity, including of the human mind, is also not just a biological process but rather a complex process (Veresov, 2010: 84). A Christian Philosophy of Education would be in agreement with these viewpoints.

6. CONCLUSION

Despite having originated in secular contexts, the CHAT has shown promise as an instrument that can help convey to current and future educators (such as student teachers) in theoretical-philosophical terms what a Christian Philosophy could entail in a postmodern and post-post-modern context. On the one hand, a Christian Philosophy of Education based on Biblical perspectives utilising the basic tenets of the CHAT (subject, object, mediating artefact, rules, community, division of labour) is sufficiently tentative for it not to be mistaken for a grand narrative regarding Christian education, while on the other it is also sufficiently compact and coherent for it not to be mistaken for a "grab bag" of Biblical perspectives. A Christian or Biblical Philosophy of Education as outlined above could be useful for introducing young parents, prospective teachers, caretakers and other educators to the task of educating in accordance with the commitments expressed in Christian parents' baptismal vow.

7. REFERENCES

Asghar, M. 2013. Explorative Formative Assessment using Cultural Historical Activity Theory. Turkish Online Journal of Quantitative Inquiry, 4(2): 18-32. April. [ Links ]

Christian Reformed Church, 1991/1994, Service for baptism (1991, approved 1994). (Accessed on 5 May 2016 at: https://www.crcna.org/resources/church-resources/liturgical-forms-resources/baptism-children/service-baptism-1991-approved) [ Links ]

Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. 2011. Research methods in education. London, Routledge. [ Links ]

Coletto, R. 2008. When "paradigms" differ: scientific communication between scepticism and hope in recent philosophy of science, Koers, 73(3): 445-467. [ Links ]

Coletto, R. 2009. Strategies towards a reformation of the theology-based approach to Christian scholarship. In die Skriflig, 43(2): 291-313. [ Links ]

Colson, C. 2001. The Christian in Today's Culture. Wheaton Ill., Tyndale House Publishers. [ Links ]

Halverson, C. A. 2002. Activity theory and Distributed Cognition: Or what does CSCW need to do with theories? Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 11: 243-267. [ Links ]

Gumede, W. & Dikeni, L. 2009. South African Democracy and the Retreat of Intellectuals. Sunnyside, Jacana Media. [ Links ]

Lampert-Shepel, E. 2008. Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) and case study design: A cross-cultural study of teachers' reflective practice. International Journal of Case Method Research & Application, 20(2): 211-227. [ Links ]

Klapwijk, J. 1989. On Worldviews and Philosophy. In: Marshall, P.A. Griffioen, S. & Mouw, R. J. (eds), 1989, Stained Glass: Worldviews and Social Science, Lanham, UP of America (pp. 41-55). [ Links ]

Maistry, S. 2014. Education for Economic Growth: A Neoliberal Fallacy in South Africa. Alternation, 21(1):57-75. [ Links ]

Media Club South Africa. Fast Facts, 2016, Accessed on 7 April 2016 at: www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com/landstatic/82-fast-facts [ Links ]

Merriam, S. B. 2009. Qualitative Research. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Miedema, S. & Ter Avest, I. 2011. In the flow of maximal interreligious Citizenship Education. Religious Education, 106(4): 410-424, July-September. [ Links ]

Nolan, A. 2009. The spiritual life of the intellectual. In: Gumede, W. and Dikeni, L., 2009, South African Democracy and the Retreat of Intellectuals, Sunnyside, Jacana Media. (p.46-54). [ Links ]

Olthuis, J. H. 2012. A vision of and for love: Towards a Christian post-postmodern worldview. Koers. Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, 77(1), Art #28, 7 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/koersv77i.28 [ Links ]

Owen, J. 2003. Christian Psychology's war on God's Word. Stanley N C, Timeless Texts. [ Links ]

Parsons, T. 1973. A Seminar with Talcott Parsons at Brown University: My Life and Work. The American Journal ofEconomics and Sociology, 65(1): 1-58. [ Links ]

Parsons, T. 1990. Prolegomena to a Theory of Social Institutions. American Sociological Review, 55(1); 319-333. [ Links ]

Parsons, T. 1996. The Theory of Human Behavior in its Individual and Social Aspects. The American Sociologist, 27(4): 13-23. [ Links ]

Pew Research Center. 2015. The future of world religions: Population growth projections, 2010-2015. Accessed on 12 July 2016 at: www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010-2050/ [ Links ]

Postholm, M.B. 2015. Methodologies in Cultural-Historical Activity Theory: The example of school-based development. Educational Research, 57(1): 43-58. January. [ Links ]

Schreiner, P. 2005. Religious education in Europe, Oslo: Comenius Institute, Oslo University. 8 September. (Accessed on 9 Nov. 2012 at: ci-muenster.de/pdfs/themen/europa2.pdf) [ Links ]

South Africa, Departments of Basic and Higher Education and Training. 2009. Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development in South Africa. Government Gazette #38487. [ Links ]

Stetsenko, A. & Arievitch, I.M. 2004. The self in Cultural- Historical Activity Theory. Theory and Psychology, 14(4): 475-503. [ Links ]

Strauss, D.F.M. 2009. Philosophy: Discipline of the Disciplines. Grand Rapids, Paideia Press. [ Links ]

Strauss, D.F.M. 2014. A philosophical approach to Law and Religion. Paper read at: The Second Annual Law and Religion Conference, Stellenbosch. May 26-28. [ Links ]

Sumptner, T. 2010. Baptism and Christian education, Credenda Agenda, 9 Aug. (Accessed on 5 May 2016 at: www.credenda.org/index.php/Culture/baptims-and-Christian-education.html) [ Links ]

Van der Walt, J.L. 2015. Education from a post-post- foundationalist perspective, and for post-post-foundationalist conditions. Koers (Bulletin for Christian Scholarship), 80(1). #2211, 8 pages. [ Links ]

Veresov, N. 2010. Introducing cultural historical theory: main concepts and principles of genetic research methodology. Kulturno-Istoriceskaia Psigologia, 4: 83-90. [ Links ]

Weeks, S., Herman, H., Maarman, R. & Wolhuter, C. 2006. SACHES and Comparative, International and Development Education in South Africa. Southern African Review of Education, 12(2), 5-20. [ Links ]

White, L. 2012. Curriculum support groups as ecologies of practice for teacher development. Unpublished thesis, Johannesburg, University of Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Wilson, D.D., Cole, M., Nixon, A.S., Nocon, H., Gordon, V., Jackson, T., Garia, O.L. & Minami, Y. 2013. Qualitative research: Cultural-historical activity theory. In: McGaw, B., Peterson, P. & Baker, E. (Eds.) 2013, International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd Edition, New York, Elsevier. [ Links ]

Xiao, J. 2015. Studying what's taught: Islamic education around the world, The Humanist.com. 7 April. (Accessed on 3 March 2016 at: the humanist.com/commentary/studying-what's-taught-Islamic-education-around-the-world) [ Links ]

Yamagata-Lynch, L. 2010. Understanding Cultural Historical Activity Theory. In: Yamagata-Lynch, L., 2010, Activity Systems Analysis Methods: Understanding complex Learning Environments, Dordrecht, Springer (p. 13-26). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Johannes L. van der Walt

PO Box 40, Woodlands, 0072

South Africa

Email: hannesv290@gmail.com

31 Oct 2016