Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Koers

versão On-line ISSN 2304-8557

versão impressa ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.80 no.4 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.80.4.2243

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.80.4.2243

Voltaire: natural scientific light against christian criminality - methodologies of targeting

JJ (Ponti) Venter

School of Basic Sciences North-West University (Vaal Triangle Campus) South Africa

ABSTRACT

Western thought, since the Renaissance, shows a repeated development of methods aimed at attacking Christianity, from Machiavelli's Classicist militarism up to William James' 'empty' Pragmatism.1 Methods have aims, and aims are subject to norms and criteria. A summit of anti-Christian enmity - in middle Modernity - was the pre-Revolutionary French philosophes, headed by Voltaire. In the previous article I have shown how the Neo-Classicist Voltaire developed a hermeneutic in which the Classical Greeks and Romans always appear as tolerant and virtuous, and Christianity is presented as misleading, intolerant, oppressive, violent and criminal - all through its history. In this article I investigate the nature of 'light' in the name 'Enlightenment', in order to understand Voltaire's alternative to Christianity. I argue that the philosophical term 'light' was rooted in Plato, developed and adapted by Augustine and Scholasticism, and became a basis for group mystical elitism in Joachim of Fiore. In Modernity - specifically Voltaire - the light becomes a replacement of the Medieval divine Logos (Law-word) - a new light for elitist groups. Modernity separated the Origin (causa efficiens) from the Destiny (causa finalis): the divine was split between 'Nature' (origin) and (super-natural) 'Rationality' (scientific and civil); linked these two with the faith in progress. The 'light' was insight into 'natural law' a priori in consciousness; an ambiguous 'natural law' expressing the bio-mechanical and the basis of civility, driving humankind to progress. Thus insight into the laws of physics - from Logos Newton via Caesar Voltaire - provides the basis for a rational society: scientific reason supports practical reason. Voltaire's insistence on the natural right of women to be incubators of workers and soldiers (adopted by the French Revolutionaries) shows how difficult it was to derive the human from the natural.

Key Terms: Logos, light, Newton, Plato, Augustine, natural law, naturalism progress, scientism, causa efficiens, finalis, hermeneutics

ABSTRAKTE

Die Westerse denke, sedert die Renaissance, toon herhaalde ontwikkeling van metodes bedoel om die Christendom aan te val, vanaf Machiavelli se Klassisistiese militarisme tot by William James se 'leë' Pragmatisme. Metodes het doelstellings, en doelstellings is onderworpe aan norme en kriteria. 'n Hoogtepunt in anti-Christelike vyandskap - in middel-Moderniteit - was die pre-Rewolusionêre Franse philosophes, gelei deur Voltaire. In die vorige artikel het ek laat sien hoe die Neo-Klassisis Voltaire 'n hermeneutiek ontwikkel het waarin die Klassieke Grieke en Romeine altyd as verdraagsaam en deugsaam verskyn, en die Christendom voorgehou word as misleidend, intolerant, onderdrukkend, gewelddadig en krimineel - regdeur sy geskiedenis. In hierdie artikel ondersoek ek die aard van 'lig' in die naam, Verligting, om so Voltaire se alternatief tot die Christendom te verstaan. Ek argumenteer dat die wysgerige term 'lig' op Plato teruggaan, ontwikkel en aangepas is deur Augustinus en die Skolastiek, en by Joachim van Fiore 'n basis vir mistieke groepselitisme geword het. In die Moderne era - in besonder Voltaire - word die lig 'n vervanging vir die Middeleeuse goddelike Logos ((Wet-woord) - n nuwe lig vir elitistiese groepe. Moderniteit het die Oorsprong (causa efficiens) geskei van die Bestemming (causa finalis): die goddelike is gesplit tussen die 'Natuur' (oorsprong) en die (bo-natuurlike) Rasionaliteit (wetenskaplik en siviel); die twee is verbind deur die progressiegeloof. Die 'lig' was insig in die 'natuurwet' a priori in die bewussyn; 'n dubbelsinnige 'natuurwet' wat beide die bio-meganiese en die basis vir burgerlikheid uitdruk; dit dryf die mensheid na vooruitgang. Dus voorsien insig in die fisika se wette - van Logos Newton via Caesar Voltaire - die basis vir 'n rasionele samelewing: die wetenskaplike rede ondersteun die praktikale rede. Voltaire se aandrang op natuurlike reg van vroue om broeimasjiene te wees van werkers en soldate (deur die Franse Rewolusionêre oorgeneem) toon hoe moeilik deduksie van die menslike uit die natuurlike was.

Sleutelterme: Logos, lig, Newton, Plato, Augustinus, natuurlike reg, naturalisme-vooruitgang, scientisme, causa efficiens, finalis, hermeneutiek

1 THE 'LIGHT' OF THE 'EN-LIGHTEN-MENT'

How did Voltaire intend to crush the head of the infamous? The negative side of Voltaire's attack was Neo-Classicist: show how good the Classical people were, and how twisted the minds of the Christians were in Ancient times and at present still are. On the positive side the process of rational enlightening was supposed to do the trick. In the following quote the elements of his conception of enlightenment are brought together:

[1] Damned be a people imbecile and barbarous enough to think that there is a God for his province only: this is blasphemy. What? The light of the sun illumines all the eyes, and the light of God enlightens only a small and sickly nation in a corner of the globe! What a horror! What folly! The divinity speaks in the heart of all human beings and the bonds of caring love unites them from one end of the universe to the other (CC, 1764:109-10).

Voltaire's work is spread out over short essays, dictionary inscriptions, literary works and catechisms. Enlightening means activating (divine) innate natural law, like activating Stoic (Cartesian) innate ideas from the "heart" into reason as universal laws for the universe and all humankind. Voltaire here only refers to that aspect of natural law that concerns inter-individual human bonding, but elsewhere, especially in his Elemens de philosophie de Neuton2 (EN, 1739) the laws for the bio-mechanical world were included. The parallel between God's physical light (the sun) and his moral light (the commandment of love) is not accidental: as middle Modernity unfolded (especially after Quesnay and Turgot), the sub-rational (in humans the "instincts" and "sentiments") became the home of all law: this really was "divine light". The term "province" (with "a people") again is not to be overlooked: Voltaire (like almost all of his contemporaries) believed it to be the totalitarian state's task to ensure enlightenment of the people.3

The faith in progressive enlightenment required a historical determinism. John Calvin, the one usually accused of introducing a stern legislating pre-destinator, in fact used a variety of Biblical metaphors to describe a caring God4. It was Descartes with his intellectualistic and mechanistic metaphors who reduced the Thomistic idea of God to a deterministic (almost mechanical) legislator. Voltaire's God was a Cartesian legislator. In the Poem on the Lisbon disaster he viewed God as particularly bound by his laws. He also found it difficult to distinguish human caring "love" (here indicated as divine morally enlightening law), from deterministic, bio-mechanical, eroticism and animal desire (see AM, AP, AS, 1764).

"Enlightenment", "natural law", (bio-)"physics", "instinct", "sentiment", "innate", "moral science" and "morality" have all been closely associated since the beginning of the 18th century. Vico still tried to separate physical natural law from social natural law, with God as the archetypal legislator for both5. But exactly his archetypal conception of God-and-law (derived from especially the Alexandrine Neo-Platonist Church Fathers), allowed for a deterministic Law-god. The Janus-like faith-in-progress with Nature as Origin and Human-Divine (mostly civil) Rationality as Destiny, needed to link natural processes with human processes. Quesnay, for whom enlightenment exactly meant the emancipation of the citizen into full knowledge of natural law, unified the physical with the moral law:

[2] Natural laws are either physical or moral. One understands here under 'physical law' the regular course of every physical event which is evidently the most advantageous for humankind. One understands here under 'moral law' the rule of every human action conforming to the physical order which is evidently the most advantageous for humankind. These laws form the ensemble of what is called 'natural law' (Quesnay, 1965:374-5).

Quesnay was the leader of the Physiocratic economistic philosophes. They defended a free agricultural market, for agriculture they considered as the basis of civil society. Quesnay's conception of enlightenment already shows the emerging base-superstructure model: the state is criminal if it does not educate the citizen to understand the advantages to be taken from the physical world and does not allow them the freedom to do this. The divine light is mirrored through advantageous physical regularities - "if the flame of reason enlightens the government, laws detrimental to society will soon be taken off the books"6 This specific type of unification of the "physical natural law" with the "moral natural law" was easily changed into a sensualistic naturalism by Turgot; Voltaire followed him closely.

Forms of the word 'light' were quite widely used to indicate Les Lumières (The En-light-eners) in France, the Aufklärung (literally "clearing up") in Germany and also 'Enlightenment' in the UK and the US. Voltaire sometimes used the term éclairé ("clarified" or "brightened up"). The idea of "being-clarified" is reminiscent of the Cartesian "clear and distinct" perceptions; a mind that perceives brightly! The clear links between such perceptions are perceived by direct intuition: a humanised Augustinian insight sustained from Ockham via Descartes and Locke, the philosophes, Kant's "purification" of reason, up to Husserl. The requirement of seeing a necessary connection has always been there. Being-enlightened can thus also be seen as having Cartesian clarity of mind. An essay in which derivations of terms like "light", "clarity", "purity" forms a whole discursive network is the Advice to a journalist, where journalistic treatment of science and the arts is discussed in detail (cf. further CJ, 1739).

Historically the 'light' motif has Ancient sources. Firstly the metaphor of an intellectual "sun" in Plato's works, that has connections with Ra and Helios in mythology, and especially given new life in Egyptian Neo-Platonism, adapted by the Alexandrine Church Fathers, who fused it with the Biblical Logos into God's illuminating Word. Augustine adapted this further in his idea of a three-phased mystical road: the sensuous level of faith, the practical level of reason, and the illumined level of the intellectual in direct contact with divine law. This tripartite individual mystical road was changed into a world history of groups in a climbing order to the New Jerusalem by Joachim of Fiore (1132-1202)7. Vico drew heavily on this tradition. Some Moderns changed this into phases of the faith in progress, thereby constructing a group elitism of enlightened initiates.

In the 13th century, however, Thomas Aquinas, following Aristotle, assumed that knowledge only originated in sensory experience. He denied a direct super-natural light that brings insight into natural (i.e. God-given) law, arguing that reason has an innate light that sees natural law internally when stimulated by experience. Descartes radicalised the inner sight (innate Ideas); Locke accentuated the role of sense experience. In Locke this led to a double conception of law: on the one hand rational intuition intra-mentally linked up experiential fragments to create archetypes; these archetypes then had to be measured against given divine law.8 Voltaire radicalised Locke's 'empiricism' into a sensualism similar to Turgot's.

One link more ought to be mentioned: the Renaissance and early Modern recovery of Platonism. Some studies have been done about the pre-Enlightenment, especially regarding 'free thinking' in Europe in the vicinity of Spinoza and Descartes and their 'Orthodox' opposition. Not much is said about the idea of 'light' as such: it is rather all about 'reason'. The Protestant orthodox opposition reverted to different forms of Scholasticism, by and large Augustinian forms of Neo-Platonism as well as (platonising) Thomism. Among the Cambridge Platonists Cudworth, who was well-acquainted with the Dutch orthodoxy, and the Remonstrants distanced themselves from the 'atheist' Spinoza. Colie, in Light and Enlightenment, A study of the Cambridge Platonists and the Dutch Armenians, highlights the following:

[3] The Art of Divinity, properly speaking, had but the light, intelligence, and wisdom that is in God Himself, and is of a nature that is so far removed from that of bodies that it cannot be mingled with corporeal nature. Nature herself is not this Art Archetypal, or Original, which is in God; she is but a copy or an imprint, which, though living and in many respects like the Original in how she behaves, nevertheless cannot understand the reason why she behaves (Colie, 1957: 130).

A sentence like this one could be found in any of the great Scholastics, be it an 'Augustinian' (e.g. Bonaventure) or an 'Aristotelian' (such as Thomas Aquinas). The Modern idea of 'nature' as a person that speaks is eliminated, using the archetype-ectype idea that we find in synthetic Christianity. It is a defence of Theology itself as a kind of rational revelation somehow directly from God (illumination) and/ or via the analogies and images of Him in creation. The Orthodoxy, the Cambridge Platonists, the Remonstrants, Locke somewhere in between, then Vico and up to Husserl - all these Christians were trying to defend the divine origin of the law by trying to outdo Rationalism (each in his own way), using his own form of late-Scholastic rationality. In fact they undid the work of the Reformers. The idea of "light", however, was easily and quite soon adopted into a secular, purified natural theology under the influence of Descartes, Hobbes and others, purified from the traditional "orthodoxy" of the Cambridge Platonists.

Some say that the Medieval idea of "natural law" intended a restriction against human depravity; the Modern interpretation of it is rather a liberation towards human autonomous rational design (cf. Willey, 1961:167; Chalk, 1951:333). This is a misunderstanding: as Modernity progressed, the conception of reality - including the idea of God - was progressively modelled on physical law; the beginning of Montesquieu's famous L' Esprit des lois (1748):

[4] Laws, in their most extended signification, are necessary connections that follow from the nature of things; and in this sense all beings have their laws, the godhead had his laws, the material world has his laws, the intelligences superior to human beings have their laws, the brute animals have their laws, humankind has its laws. ... There is therefore an original Reason and the laws are relationships between it and the different beings, and the relationships between the diverse beings among themselves. God needed a relationship with the world, as creator and as conserver: the laws according to which he created are those according to which he conserves. He acts according to these rules because he knows them; he knows them because he has made them; he has made them, because a relationship between them and his wisdom and power was necessary (1748: 29).

The thought of Descartes implies a similar view of God in relationship to the world. The definition of law in [4] is found one century later repeated by Auguste Comte. In spite of his Humanistic deification of freedom, the world of middle Modernity was a more essentialist and rock-hard nomism9 than that of Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, Calvin or Newton. (These latter two allowed for a more "voluntarist" idea of God.) The most serious influence in the direction of a completely nomistic determinism was probably the reduction of "science" to the deductive model of mathematics and physics. A mechanical God creates by deducing causes that have determined effects; a mathematical God calculates and works from the ideas of perfect circles and straight lines according to the fixed rules of abstract calculation: God's omnipotence cannot recalculate 2+2 into 5 or 3. Confronted by Bonaparte about the absence of a world-creator from his theory, Laplace is said to have answered:

[5] This hypothesis, honourable Sir, in fact does explain everything, but does not allow to predict anything. In as far as being-a-scholar, I have to furnish myself of work that permits predictions (Laplace, 2012). Direct quote?

Laplace's statement was thus not the simple 'atheist' one of not needing the hypothesis of a creator-god. It is rather anti-metaphysical (early positivist) statement of Cartesian science as power - prediction (based upon fixed causal law) is the basis of mastery (science as explanation - especially in terms of origins - went into the theological-metaphysical dustbin).10 Voltaire himself preferred the metaphor of a legislator god above that of the craftsman (cf. Voltaire, CC, 1764: 84-5).

This granite reality of a Law-world-god had its counter-part in the "emancipation project" of the Enlightenment; according to Kant (1783, Was ist Aufklärung?) a process of mental self-liberation:

[6] Enlightenment is the exiting of the human being out of his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to engage your own understanding without the leadership of another. This immaturity is self-imposed if the cause of it does not lie in a lack of understanding, but in a lack of decisiveness and courage to put your own understanding to use without the leadership of another. Sapere aude! 'Dare to put your own understanding to use!' is thus the slogan of the Enlightenment (Kant, 1975:53).11

Kant next attacks the leaders for keeping the people dumb. He was not the first: the whole project of the French Encyclopédie and the 18th century philosophers was aimed at enlightening the immature and superstitious, especially against priestly subterfuge.12 In Kant's narrative there is naturo-historical movement from animalism to civil culture; the upwards natural driving forces of unsociability (conflict, competition, war) coerce human beings into sociability (covenants for own protection) by balancing competitive powers with a rational, civil order as outcome. This is the en-lighten-ing process.

The problem was that the granite law-fixed reality was an essential requirement for the doctrine of emancipation: the autonomous individual subject could not emancipate itself; its free choices were taken into a veritable ocean of the great historical "market" mechanism. Whereas Kant's near predecessors got stuck in totalitarian state practicalism, la raison de l´ état being the controlling subject of the subrational and of full emancipation, Kant moved beyond this to an internationalist critical practicalist idealism: all individual choices are absorbed into a fixed-law naturo-cultural history.13

Voltaire was a somewhat younger contemporary of Turgot, situated between Vico and Turgot on the one hand, and the 'younger' Kant on the other. Philosophically Voltaire was an essayist, a dictionary writer, and a storyteller, rather than a systematic thinker. In style and form he anticipated Nietzsche rather than Kant. But he shared many themes with especially Turgot and Kant and also with the 17th century liberals: Locke and the Cambridge Neo-Platonist, Wyermars14. His instance on tolerance and human dignity have a Lockean ring; his allegorical Bible satires remind one of Myers who viewed all of the Genesis creation story as but allegory; his scientistic, sensualist view of good knowledge generation was near Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz, but especially Turgot. But he had a good sense of the practice of life founded mostly on the sub-rational; yet he aimed at progress towards practical rationality in a tolerant, completely secular civil society with strictly Hobbesian (ancient pagan) control over religion. He remained in the mode of la raison de l´ état.

Importantly, though not terminologically so, Hobbes and the Physiocrats had established a mode of thinking-from-the-substrate: from nature and the material base to culture and reason. This was the framework of Voltaire's ontology.

2 AND THERE WAS LIGHT: SCIENCE AND PROGRESS

The "light" ("clarity", "purity") of the Enlightenment was by and large the purity of rational (a priori) insight into the "law" (usually called "natural law" or "law of nature").

This mostly encompassed scientific rationality as well as practical rationality; though quite some adherents of pure scientism remained in this company. The bottom-upwards thinking of Modernity usually placed the rationality of mathematics and physics first in line.15

2.1 Science as light in a world view context

For a start one can look at Voltaire's hopes from another angle: the way of becoming enlightened, of sourcing the light, namely providing informative knowledge. This was the reason for the Encyclopédie Française and for Voltaire's own Dictionnaire Philosophique.

The Encyclopaedists and Voltaire seriously believed that people had been drenched in misinformation and superstition by the powerful, notably the priesthood16 - a true appreciation of the situation. Natural science was Voltaire's hope; together with companion, Emilie du Chatelet, he popularised Newton all over Europe, and with the English author, Pope, he could say:

[7] 'Nature and nature's laws lay hid in night; God said 'Let Newton be' and all was light.'

Voltaire's Dictionnaire Philosophique . is neither a dictionary nor is it simply philosophical. Under alphabet letters A to E - following the French order - one finds inscriptions such as 'Abraham', 'soul', 'friendship', 'love', 'angel', 'anthropofages', 'Apis', 'beasts', 'Sovereign Good', 'limits of the human spirit', 'certitude', 'heaven among the Ancients', 'body', 'Chinese', 'Catechism of the Chinese', 'Catechism of the gardener', 'destination', 'God', 'equality', 'hell', 'Ezechiel'. These are sometimes approached as criticisms of views, often attempting to cast doubt on age old traditions as but primitive credulity, again as satirical amusement of the strange ways of humankind, sometimes in the form of Socratic dialogues or religious catechisms, based upon illustrative fables or personal experiences. Hidden was an ontological commitment to the Universal, Supreme Good as legislator-creator, the immortality of the soul, reward and punishment after death; a life of justice under natural law (the laws of physics and morality).

The intention was popular education, enlightenment of the public, removing ignorance and giving good information in a pleasant and digestible way. The literary inclinations of Voltaire often lead to exaggeration, twisting the facts, substituting one piece of guesswork with an imaginative other, bordering on propaganda. He kept courage though, even when faced by exile or the Bastille.

2.2 En-lighten-ment - cultural context and symbols

History has bequeathed us quite expressive pictures of Voltaire's reception of the En-lighten-ment thematic. Central to both pictures is the reflection of divine light onto the world.

Plate A is the frontispiece to Voltaire's Elemens de la Philosophie de Neuton (1738); his interpretation of Isaac Newton's work. Voltaire, philosophe, sits at a desk, translating the inspired work of Newton. The manuscript is illuminated by a divine light coming from behind Newton, reflected down to Voltaire by a muse, representing Voltaire's mistress Emilie du Chatelet, who actually translated Newton and collaborated with Voltaire to make sense of Newton's work.

Plate B is the - almost iconic - frontispiece of Vico's Scienca Nuova (first edition 1725; second 1730, third 1744). The Sun provides light to lady Metaphysics, who in ecstasy sees into the divine mind via the all-seeing eye of divine Providence, standing on physical nature (the object of natural philosophers), resting, only partially, on the altar of pagan religions. On the zodiac are the signs of Leo - agri-culture as mastery, studied by Viconian social science, and Virgo, indicating the advent of religious time reckoning based upon agriculture. The divine light is reflected via a convex jewel (the required purity of heart: spirit as opposed to bodily smut by the metaphysician) spreading its rays of public and civil morality worldwide. This also specifically onto Homer, who was the first to record this revelation (crudely). All culture began with religions, therefore the altar. On ground level are hieroglyphs indicating culture: transport (migration), agriculture (settlement), popular or vulgar literacy (alphabets) and the fasces, symbolising unity and authority of original paternal states: 'wars are waged so that people may live in peace' (Vico, 1984: 1-18).

Importantly, though Vico has agriculture early in the row of cultural development, he founds all culture in religion and his view of culture encompasses a wide variety of human functions. This is not yet the complete semi-materialist base-superstructure idea one finds soon after in the capitalist class thinker, Turgot, according to whom the interaction between human senses and the earth produced the first form of culture: agri-culture (cf. further Turgot, 1973, chapter 3 ff.). Noteworthy in the Enlightenment context, Turgot finds the language of the farmer to be the first format of the (quasi-mathematical, scientific) expression of natural law. He was a Physiocrat who believed that nature governs (through sensualist empirical science).

0926: Minerva and the Muses. Detail of painting by Hans Rottenhammer 1564-1626. Germanisches National Museum, Nürnberg. Note the erotic fleshy bodies accentuated by the colour contrasts, the open breasts, the nude cupids all around. Minerva (since 2nd century BC identified with Athena), standing at the back dressed soldier-like and armed, goddess of wisdom, medicine, arts, colour, science, trade, and, notably, of WAR. She wears a see-through dress, accentuating her femininity, but combined with male, soldier attire. Four of the Muses have musical instruments (even a piano!); a violin is lying on the ground and a book lies between the feet of Cupid. A playful atmosphere, quasi innocent, youthful. A Pan-like nature-spiritual atmosphere pervades this detail. The Cupids are independent (standing and running on their own feet) (cf. Parada & Maicar, 2012).

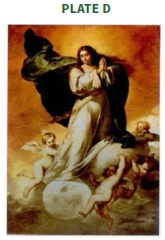

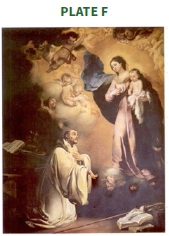

Plate D Immaculate Conception (1678), E Immaculate Conception (1655), F St Bernard and the Virgin (1655), by Murillo. In the 1655 and 1678 paintings Mary had just received the message that she was expecting the Saviour, and she conserved the message in her heart. Her face is one of wonder; she apparently stands on the moon and a cloud and is supported by baby-like angels. The angels are in amazement and adoration. St Bernard is seen in adoration of Mary in Plate G. She has baby Jesus in her left arm, and has an open breast so as to feed the baby, but is looking at the Saint. St Bernard is pointing to the Scriptures: 'so that the Scriptures may be fulfilled...' The central spaces of the paintings are illumined, but the source of light is hidden. The atmosphere is one of wonder, silence, humility, adoration and upliftment (cf. further Garin, 1995:32-34).

3 THE HI-STORY OF HUMAN EMANCIPATION

The similarities between the Vico frontispiece and the VoltaireNewton frontispiece (Plate A and B) may provide some explanation as to the shifts in the intellectual atmosphere of the age. The pretence of the Enlightenment was emancipation aided by scientific knowledge under the leadership of reason. This was not easily done, tripped up constantly by the Reason (the elite) who imposed its sense of emancipation. By the mid-twentieth Horkheimer would write about the 'end of reason', others about 'the end of the subject'; yet others about 'the end of man' or 'the end of history'. Of course 'reason', 'subject', 'man' and 'history' have been largely overlapping categories: the end of one would imply the end of the others.

3.1 Reality as history

In the era from Defoe (1661-1731) up to Kant, Hegel and Fichte, a new view of reality and history came into being: Lessing had recovered Joachim of Fiore's mystical view of history, and Rousseau had re-invented the state as a mystical unity.

Against the background of the idea of group mysticism (following the Joachimist tradition) reality was believed to be in progress with the human being as the leading light. Natural history and human history were in one another's extension. In fact the history of humankind was seen as the history of god-becoming-in-the-world - through self-loving competition, science, technology, and organisation in a civil community. The poisonous sting of the faith in progress lies in the assumption that some humans have a natural advantage and right of control over others, as groups, races, or nations. Defoe's (especially Robinson Crusoe) characters represent groups, such as a rational Western world traveller, Crusoe, would have met. Crusoe sets about enlightening them, guided by Lockean tolerance. But note: in Defoe history is 'storied' - it is an imaginative narrative reading contemporary cultural 'levels' back into history. Within decades Vico developed this into the earliest Modern 'scientific' method of historiography.

The 'enlightened' often want to be good to the 'unenlightened'. This was rooted in the Platonist and Augustinian views on 'illumination': the distinction between philosopher-kings and other citizens in Plato, and between clericals and laity in the Medieval Church. Modernity had some dangerous roots in Medieval illuminative mysticism. Medieval mysticism, however, was mostly individual; Modernity's had become a dangerous, very elitist, group mysticism (mostly centred in the state). The Modern illuminatus was/ is the very opposite of the Medieval mystic in many respects. He (not much of a 'she'), has been seen (and acted as) part of a collective - a collective superior to its predecessors; an elite, claiming high office on the basis of scientific or rational insight (guided by intellectual intuitions). Depending on how 'crafty' one was, one could reach the summit in and of the collective. In the frontispiece of Voltaire's Elémens de la philosophie de Neuton (Plate A) almost everything about Modernity's idea of 'illumination' or en-lighten-ment is condensed. Voltaire, the Caesarist centre of the picture, did not draw this illustration himself, but he surely approved of it. In a later essay Voltaire explicitly propagates the Platonist ideal of the philosopher as disinterested adviser to the prince, and even the ideal of the philosopher king (cf. DSDP, 1750: 8).

3.2 Divin-atory science

Voltaire, prime mover against superstition, in Plate A establishes Newton himself as a 'divinity'. Newton is located in heaven measuring the universe, with one of the Muses, symbol of inspiration or illumination, in this case in feminine subjection (but in control of her status), projecting the light from Newton to Voltaire. The latter works at his desk with a mere earthly globe near him. The Muse, (in fact his mistress), here replaces Vico's 'Maiden Metaphysical Theology'. In a still very male dominated context, that of natural science, Voltaire at least recognised the major contribution made by the woman in his life. Pre-Christian mythology provided him with support: the Muses were female, all nine of them, giving and revealing intellectual culture to humankind. In Plate C the traditional erotic context is quite up front; so also in the Voltaire frontispiece. This has Ancient roots: Aeschylus lets the 'humane' god, Prometheus, claim invention of intellectual literacy, revealed via the Muses:

[8] Yes and numbers too, chiefest of sciences, I invented for them, and the combining of letters, creative mother of the Muses' arts, with which to hold all things in memory (Prometheus to the Oceanids; Aeschylus, Prometheus bound, 460; in Parada & Förlag, 2012:1).

Voltaire wears the laurel wreath of a Roman official (a Caesar), not the angelic halo of a Catholic saint. The scientific writer is becoming Caesarist. In Plate G above St Bernard is down on his knees in total submission: his vision is that of the fulfilment of the Scriptures in the baby Jesus; this is all he has. Newton and Voltaire have instruments of geometry and construction nearby: squares, fitters, et cetera. Instead of Vico's religious and socio-cultural hieroglyphics down below, Voltaire is surrounded by Masonic instruments including the triangular level that became the symbol of perfect balance during the Revolution (probably reflecting the perfection of the equilateral triangular face of the Providential Eye - divine reason, the Supreme Revolutionary).

In Rotthammer's painting Minerva, the goddess of war, is also the goddess of fine and intellectual arts, that is 'numbers, the chiefest of sciences' and 'the combining of letters, creative mother of all the Muses' arts' (quote [8]). This mixture of Roman militarism and intellectual culture is present in Voltaire and in all of Modernity since Descartes (geometrical designer of weapons) and Hobbes.

Voltaire is thus a diviner in a double sense: making a divine out of a scientist and divining his message via a Muse. For at the second level the erotic Muse is sitting, mirror in hand. She reflects the Logos' light down to Voltaire. The genitally nude Cupids hang from her dress and legs - cupiditas under control of scientia according to the Modern sense of purity? The eroticism seen in the Rotthammer painting is present too, but the relationships are different: Rotthammer's Cupids, in the face even of Minerva, walk about freely on own feet on the ground.

If one compares Plate A's Muse with the Catholic idea of purity, Mary in Murillo's two Immaculate Conceptions (1650 and 1678) and St Bernard and the Virgin (1655) (Plates D, E and F), another shift Voltairean shows itself. In the Conceptions Mary has one foot on the moon, the age old symbol of femininity, and the other on a cloud. She is supported by angels, indicating her human dependence on heaven. The angels are nude and babylike, but the genitals of those in front are tactfully covered by cloth. In the first painting Mary is praying in amazement about what is happening to her; in the second one she 'conserves in her heart' - by crossing her hands over her chest - what the Holy Spirit revealed to her. Even though it represents a very human event, a 'conception', there is nothing erotic or sexual in the paintings. Mary is fully dressed and spiritual in attitude.

The Voltaire-Newton frontispiece is symbolic of the return of Classical science (theoretical reason) and eroticism (will as desire): the Muses' open breast is protruding in a challenging way. Love, as Voltaire understood it, was a human form of desire. Murillo's St Bernard and the Virgin (1650-1655 - Plate F) shows a similarly open-breasted Mary, shyly uncovering her left breast with her fingers, in the way of a mother preparing to nurse a baby. Again nothing challenging or erotic. The Christ-baby is in her right arm, but she is looking at St Bernard as if offering to nurse also the mystic. In the Voltaire frontispiece there is nothing of this shyness. The Muse's breast is challenging, in fact flirtatious: to nurse on the one hand but on the other confidently occupying a position in 'the great chain of being', with the human Logos as keystone. The Muse is independent. A deistic God maybe the hidden light source behind Newton. Though the Cupids are dependent on the Muse's stability on high, she is important as alternative mediator, but nothing more than a mediator. She carries a mirror truthfully reflecting the divine light coming from around or behind the Logos, Newton.

Voltaire is down below with his Caesarist laurel and his Classical outfit, working at his desk - a similar dress-code was given to Minerva, as protector of Reason, in the Revolution's symbols.

We here find a structural similarity with the Medieval idea of illumination, but an antithetical difference in content. The structural similarity is this:

• a source of illumination,

• a mediator of rational or intellectual insight, and

• an intellectual or rational scholar who receives the light -

• who is mystically elevated above the common folk.

In Augustine's De Doctrina Christiana and in the major works of Anselm of Canterbury, the faithful mystic is elevated by his/ her faith into a rational or intellectual relationship with the Good (God). God illumines the mind through his mediating Logos (the Word, or Christ), in such a direct way that the mystic does not need the Bible anymore. Voltaire was a (natural) scientistic rationalist 'Masonic': thus he crowned himself with the Caesarist laurel (connected with the Mithraic cult, which was protected by Jupiter). He is sitting at his desk writing the revelations he receives; Murillo's St Bernard (Plate H) is on his knees in humble subjection in front of the Mother, referring to a revelation beyond herself.

3.3 Self-predestination

John Calvin, traditionally, has been the supposed culprit for preaching a deterministic (elitist) divine election (even though Thomas Aquinas had been more of a deterministic predestinationist). But few complain about the self-elected, naturalistic predestinationists such as Caesar-Voltaire, Turgot, Kant, Comte and Marx, up to B F Skinner. Concerning a philosophy of reminiscence: few remember the suffering caused by the doctrines of these self-appointed divine elect. Voltaire's laurel crown had consequences: scientific illumination in the form of 'scientific socialism' and 'scientistic Behaviorism'.

Voltaire was an older contemporary of Condorcet, Revolutionary minister of education who changed France's education system into technicism. Condorcet's god, 'reason', was scientific reason; Voltaire had an upper story of practical civil reason. The laurel crown signifies three things:

• Caesarism: but intellectualised. Caesarism was militaristic, in Voltaire it becomes scientistic.

• Elitism: I have access to a higher form of knowledge than the ordinary folk. I belong to the initiated, the 'elect'.

• Authoritarianism: my insights are absolute: magister ip(sissim)e dixit ('the guru, his very self, said so').

The fasces, used during the Revolution, may not have been Voltaire's choice for a heraldic emblem. However, when one eliminates Ancient atrocities from history, yet adopts a Modernised version of Ancient culture, one overlooks the foundational issues involved: Caesarism, militarism mixed with intellectualism, and the nature-freedom-culture issue. Voltaire's hermeneutic of changing the facts of the past has remained the format of revolutionary presentations of history.17

Voltaire placed his hope broadly in rational enlightenment, based upon scientific enlightenment and fulfilled in the enlightened civil society.

[7] There are some who say that, if we treated with paternal indulgence those erring brethren who pray to God in bad French, we should be putting weapons in their hands, and would once more witness the battles of Jarnac, Moncontour . it seems . illogical . to say: 'These men rebelled when I treated them ill, thus they will rebel when I treat them well'. .

The Huguenots, it is true, have been as drunk with fanaticism and stained with blood as we are; but . have not time, the progress of reason, good books, and the humanising influence of society had an effect on the leaders of these people? And do we not perceive that the aspect of nearly the whole of Europe has been changed in the last fifty years? Government is stronger everywhere, and morals have improved. .

It is a time of disgust, of satiety, or rather of reason, that may be used as an epoch and guarantee of public tranquillity. Controversy is an epidemic disease that nears its end, and what is now needed is gentle treatment. It is to the interest of the State that its expatriated children should return modestly to the homes of their fathers. Humanity demands it, reason counsels it, and politics need not fear it (1763: 5 ff.).

Voltaire's plead for the Protestants, his intervention in favour of the Calas family, gained him support in Calvinist Southern France. He heartily fought for the cause of tolerance; it is his method that is questionable. In many ways he stood nearer to Calvinism than to Catholicism, while identifying him with the latter. Given his satirical hermeneutic, his 'allegiance' to Catholicism might have been part of a game. His and other philosophes' criticism contributed much to the 'de-christianising' of France during the Revolution.

Note, however, the basis of his trust: progress in and towards rationality - the availability of good books; the human-ising influence of society. Voltaire goes quite far in this direction: 'a time of . reason, that may be used as an epoch and guarantee of public tranquillity' (quote [7]).

The close association of - almost identification - of 'rationality' with 'peace', 'tranquillity', 'justice' and 'dignity' was characteristic of early and middle Modernity. In order to account for the absence of peace, the faith in progress in terms of a doctrine of a naturally postponed or delayed rationality, combined with that of 'the reason of state', was developed. The 'natural' was seen as a state of conflict; but such conflict was creative and thus a necessary phase in human progress (cf. Venter, 1992; 2002). Voltaire rejected the Leibnizian theodicy behind this; yet he neither totally broke with the faith in progress (the role of 'self-love') nor with the belief that practical rationality based upon scientific rationality would provide a peaceful human society. In fact the quote indicates that he believed that for the French, 'reason', had arrived even among the religious war mongers. This would guarantee peace (tolerance) and all the major social goods.

inscriptions in school history textbooks as leaders fell in or out of favour with the Supreme Führer. Pol Pot - apart from the genocide of his own people - confiscated family albums and had them burnt: the people's history had to start with his revolution. Changing names of cities and streets is not simply honouring the new, but in fact an elitist revolutionary violation of historical continuity; it is in fact an exaltation of own superiority with regard to the evils of the past while usurping the good from it as if it were all your own.

4.1 In search of 'humanness'

Modernity's struggle to find the 'rational human' in the 'natural human', to establish culture as an upper storey above nature (the historical ontology of progress) was the basis of hope, lying just below the surface of Voltaire's scepticism (cf. Venter, 1999). In fact, he stood quite near the 18th century interpretations of Locke regarding natural law, such as that of Quesnay and Vico; his formulations approach that of especially Quesnay. The issue of tolerance is supposed to follow from the general a priori natural law:

[8] Natural law is that law presented to men by nature. You have reared a child, he owes you respect as father, gratitude as a benefactor. You have a right to products of the soil that you have cultivated with your own hands. You have given or received a promise; it must be kept.

Human law must in every case be based on natural law. All over the earth the great principle of both is: Do not unto others what you would that they do not unto you. Now in virtue of this principle, one man cannot say to another: 'Believe what I believe, and what thou canst not believe, or thou shalt perish.'

The supposed right of intolerance is absurd and barbaric. It is the right of the tiger, nay, it is far worse, for tigers do but tear in order to have food, while we rend each other for paragraphs ... (1763: 7).

Interestingly, some Christian, Biblical, ideas have been adopted - strongly twisted - as a priori, universal, natural law by Modernity, progressively as part of the sub-rational - the latter expressing itself more clearly in proportion as individual enlightenment grew. Such ideas have by and large been adopted from Scholasticism. Quesnay, a Modernist Roman Catholic, introduced the cyclical redefining of moral and natural in terms of each other (quote [2] above); this was used to sustain something of Medieval natural law. Voltaire here seems near Quesnay in wanting to protect freedom by founding human law on natural law (the latter in the Lockean and Medieval sense). And yet not, for he continuously derived the human from the sub-rational natural (see next section). This was related to his Enlightenment form of deism.

Enlightenment deists mostly adhered to a peculiar kind of deism: they did not propose an apathetic purely transcendent kick-starter of the world machine; rather an immanent-transcendent vague spirituality in 'nature' as the 'original'. It was/ is a 'naturo-humano-pantheistic' type of deism: (i) deistic in the sense of the absence of a personal god as well as a type of transcendence; (ii) pantheistic in the sense of a divine power present in nature; and (iii) humanistic in the sense that reason -as the humanly supernatural - emerges from nature as supreme god (mostly personalised in civil society).18

Once this is understood, Hegel's claim that his dialectics was an antidote for pantheism, becomes comprehensible: Idea and Concept means freedom, as entering into and ('later') emerging from natural necessity as opposite. However, in those conceptions where nature was simply equated with the divine (associated with perpetual stability), 'Natural Law' in fact becomes 'God'. In Comte, in spite of the adoration of Humanity-as-god, the Law is the real god. Voltaire (read his poem on the Earthquake at Lisbon, 1755; cf. also 1764-5 s. v. Tout est bien) was an adherent of this type of Deism. Hegel in fact simply explicated the dialectic already present Modernity - natural law driving beyond itself into its own opposite: humanness as super-natural. Voltaire (in quote [8]) inserts into natural law that which he wants to derive out of it: working inter-individual human relationships.

4.2 Of 'love' and 'self-love'

Thus in Voltaire the Modern naturalist always lurked nearby. Explaining love firstly in terms of animal desire and coupling, he struggles to differentiate between animal desire and its human counterpart, sexual love, to which he reduced all 'love'. Socratic (homosexual) love and pederasty are said to be notnormal, exactly because normalising it would mean extinction of the species, which 'nature' certainly could not allow. In line with this was also Voltaire's 'capitalist' side, self-love, or the preservation of the species.

[9] This self-love (amour propre) is the instrument of our conservation; it appears to be the instrument of the perpetuation of the species; it is necessary, it is dear to us, it gives us pleasure, and one ought to protect it (1764-5: s v Amour propre - author's translation). (Cf. also Amour nommé Socratique, Amour and Pédérastie.)

Modernity transformed the intellect-will issue from the Middle Ages more or less into reason-versus-desire (already in Descartes and Hobbes). From Descartes over Turgot and later Feuerbach, Nietzsche and Marx, this tension remained. When Voltaire spoke about 'self-love', 'desire' (very often murderous and selfish) had already been presented as the mechanism not only of survival, but also of progress. Voltaire searched for moderation of this.

One logically has to ask Voltaire: how do you conceive of the relationship between 'self-love' and 'tolerance'? The suggested answer was that via 'enlightenment' we would progressively become more human, more rational. However, his description of 'natural law' in quote [8], is one of cultured family life in a settled environment - this exactly fits Rousseau's description of 'civil society' in the Discourse on inequality (1958: 192) and clashes with the latter's idea of the free, pre-civil nomad. It is already way beyond the Hobbesian natural of selfishness. The relationship between self-love and humane behaviour remains unclear.

Also important is that for the sake of enlightenment of practical life, the disclosure of natural law was of necessity. The atmosphere of naturalism enforced a view of science following the model of mathematics and physics (in Locke this even goes for natural theology); the a priori basis of natural law is the sub-rational. Even where the sciences (including the 'historical' ones) are subservient to praxis, the natural science model remained dominant. Voltaire knew but three intellectual disciplines: physics, morals, and philosophy. And one has to remember that the special sciences at the time were still considered part of 'philosophy'. Broadly speaking it is the philosopher that leads the way to understanding 'natural law', i. e. to en-lighten-ment.

Since philosophers do not have any particular interest, they cannot but talk in favour of reason and the public interest (DSDP: 8).

The happiest that can overcome the people, is that the prince be a philosopher.

The philosopher prince knows that the more that reason makes progress in his states, the less will be the disputes, the theological quarrels, the warrior mentality, the superstition, do evil: he will therefore encourage reason.

Such progress will suffice to annihilate, for example, in a few years, all the disputes about grace. (DSDP: 9).

5 APPRECIATION

I love Voltaire for his penetrating criticism of everybody, also his fellow philosophes for their materialism and exaggerated mechanistic thinking, for his sense of justice, even defending those whose opinions he found disgusting, for his honest struggle with God and Leibnizean theodicy. But he formed part of a group of atmosphere creators: revolutionary terror has not disappeared since 1789. His intentions were liberal: piecemeal change of mentality by accentuation of some facts, suppression and twisting of other historical facts:

[10] Let us therefore reject all superstition in order to become more human; but in speaking against fanaticism, let us not imitate the fanatics: they are sick men in delirium who want to chastise their doctors. Let us assuage their ills, and never embitter them, and let us pour drop by drop into their souls the divine balm toleration, which they would reject with horror if it were offered to them all at once (Homélies prononcées à Londres; cf. Herrick, 1985).

I would have loved to play a bit of devil's advocate for him, but it is difficult to defend his methodology. For while preaching - note the term 'Homélies' ('Sermons') - tolerance to the intolerant, his own discourse is extremely intolerant (embittered!) at times. He found it easy to call Christianity 'the most ridiculous, the most absurd and bloody religion' ever having 'infected' the world; also to say that being religious meant having 'lost the power of reasoning'. He believed that 'every sensible and honest man' had to hold 'the Christian sect in horror' (cf. Haught, 1997). If one talks this talk, and while preaching one practically denies what one is preaching, and one is taken seriously, then one may help to support the opposite of the sermon's intention (as if all Christians were equally guilty of the atrocities committed by the powerful).

In the previous article19 I showed how his Neo-Classicist prejudices were made operational. But he did develop an alternative: a cult of science and reason - to philosophise with an Ancient authoritative approach. In another article20 I analyse his religious, enlightened, authority in the five catechisms he wrote. Here my focus was the alternative itself, specifically the meaning of 'light' in 'En-lighten-ment'. 'Enlightening', with its long history going back to Plato (and even to Ra and Helios), and its adaptations in Early Christianity and Scholasticism, always referred to the disclosure of 'divine', 'cosmic', 'universal' law, and usually called 'natural law'. Modernity, however, had brought an ambiguity into the conception of 'natural law' - it became a double-sided unity-in-opposition of the laws for the mechanical world and the laws for human life. These two were usually fused from the side of the sub-rational, mechanical.

The Modern emancipation desire began with the relinquishing of the yoke of the Roman Catholic Church during the Renaissance and the Reformation; the usurpation of this vacuum by the state, initially in the form of the absolute right of kings and later simply the absolute civil state, and the growth of science and technology since the sixteenth century with the advent of the science-technician and the Cartesian belief in universal control for the well-being of humankind.

One would want to know precisely why this happened in the Western world. Usually the motivation is searched for one-sidedly in the Greek and Roman world. But when one reads Bacon's work on method (and the utopian documents from those days), one sees a tendency to recover the coals of the gospel of peace and love from among the ashes of Church religion.

The attitude had already been: let us purify our reason from all kinds of prejudices and put our shoulders to the wheel. Optimism about human abilities under uninhibited rational work abounded. In the 18th century Vico and Quesnay explicitly base their 'optimism' about progress on God-given reason bringing insight into natural law. But surely: the contents of 'natural law' had a prescientific basis: In DSDP (1750:5 ff.). Thus his two-pronged approach: on the one hand the denigration of superstition and power abuse by Christianity (over against the pure and rational behaviour of the Greeks and the Romans) and on the other the transfer of the Classical rationality and Logos to physical science and rational insight: 'natural law' in its

Modern form is the LIGHT!

It was a reductionist light. Voltaire awards the right to the philosophising king to regulate monastic vows, for natural law directs the propagation of the human species (and the breeding of soldiers and workers. During the 1789 Revolution, after confiscation of Church property and the subjection of the clergy to a civil constitution, a cartoon appeared, entitled, Decree of the National Assembly that suppresses the male and female religious orders - Tuesday 16 February 1690, containing the following inscription:

[11] Let this day be joyful my Sisters: yes the kind names of 'mother' and 'spouse' is really preferable to that of 'nun' - it gives you all the rights of Nature as well as to us.21

This can be read as a summary of Voltaire's arguments just more than 25 years before. Note that this is more than only patriarchy: it is a reduction of especially the woman to her bio-mechanical function of being the incubator appendix of the male. Liberal naturalism was a dehumanising humanism. Could Voltaire have claimed innocence had he lived until 1812?

REFERENCES

Comte, A., 1852, Catéchisme positiviste, chez l' Auteur, Paris. [ Links ]

Condorcet. J-A-N de Caritat, 1793-4, Esquisse d'un tableau historique des progrès de l'esprit humain. Texte revu et présenté par Prior, O. H. (ed.) Nouvelle édition présentée par Yvon Belaval. Paris: Vrin, 1970. Collection: Bibliothèques des textes philosophiques. [ Links ]

Garin, F., 1995, Grandes maestros, Murillo, Aldeasa, Madrid. [ Links ]

Haught, J.A., 1985, Positive atheism's big list of Voltaire quotations. http://www.Positivatheism.org/hist/quotes/voltaire. 5 pages. Consulted 10/12/12. [ Links ]

Herrick, J., 1985, Positive atheism's big list of Voltaire quotations. http://www.Positivatheism.org/hist/quotes/voltaire. 5 pages. Consulted 10/12/12. [ Links ]

Hobbes, T., 1946, Leviathan, or the matter, form, and power of a commonwealth, ecclesiastical and civil. Oakeshott, M (ed. & introd.), Blackwell, Oxford. [ Links ]

Kant I, 1975a., Idee zu einer allgemeine Geschichte in Weltbürgerliche Absicht. In: Kant, I. Werke in zehn Bänden, hrsgg von Wilhelm Weischedel. Darmstadt: WBG. pp. 33-50. Translated into English: Kant, 1995. Idea for a universal history with political purpose, in Political writings. Nisbet, H B (tr.), Reiss, H (ed.) Cambridge: UP. pp. 41-53. [ Links ]

Kant, I., 1975b, Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung? In Kant, I. Werke in zehn Bänden, hrsgg von Wilhelm Weischedel, WBG, Darmstadt. pp. 53-102. (Translated into English: Kant, 1995. An answer to the question: 'What is enlightenment'? In Political writings, Nisbet, H B (tr.). Reiss, H (ed.) Cambridge: UP. pp. 54-60. [ Links ])

Kant, I., 1975c, Mutmasslicher Anfang der Menschegeschichte, in Kant, I. Werke in zehn Bänden, hrsgg von Wilhelm Weischedel. Darmstadt: WBG. Pp. 33-50. Translated into English: Kant, 1995. Conjectures on the beginning of human history. In: Political writings. Nisbet, H B (tr.). Reiss, H (ed.) Cambridge: UP. Pp. 221-234. [ Links ]

Parada, C & Forlag, M., 2012, Muses, Greek Mythology Link. http://www.maicar.com/GML/MUSES.html. 3 pages. Consulted 10/10/12 [ Links ]

Rousseau, J-J., 1958, The social contract; the Discourses, Dent/Dutton, London/ New York. [ Links ]

Turgot, A. R-J., 1766, Reflexions sur la formation et la distribution des richesses, http://fare.tunes.org/books/Turgot/refl_fdr.html [used 19-05-2015]. [ Links ]

Venter, J.J., 1992, 'Reason, Survival, Progress in Eighteenth Century Thought', Koers, 57, 189-214. [ Links ]

Venter, J.J., 1999, 'Modernity': the historical ontology', Acta Academica, 31(2):18-46. [ Links ]

Venter, J.J., 2002, Of nature, culture and competition, Actas del VI Congreso Cultura Europea, Pamplona, 25 al 28 de octubre de 2000. Editas por Enrique Banus y Beatriz Elio. Cizur Menor (Navarra): Aranzadi/Thomson. pp. 425-437. [ Links ]

Venter J.J (Ponti), 2013c, Methodologies of targeting - Renaissance militarism attacking Christianity as weakness. Koers 78(2), doi: 10.4102/koers.vt8i2.62. http://koersjournal.org.za/index.php/koers/article/view/62 [ Links ]

Venter J.J (Ponti), 2013d, Pragmatism attacking Christianity as weakness - methodologies of targeting. Koers 78(2), doi:10.4102/koers.v78i2.61 http://koers-journal.org.za/index.php/koers/article/view/61 [ Links ]

Vico, G., 1984, The New Science of Giambattista Vico, Unabridged translation of the third edition (1744) with the addition of 'Practice of the new science', Cornell University Press, Ithaca/London. [ Links ]

Voltaire, E.N., 1739, Elemens de philosophie de Neuton. Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Voltaire. C.J. 1739. Conseils à un journaliste In: OEuvres complètes de Voltaire, éd. Louis Moland (Paris, Garnier, 1877-1885), tome 22. http://artflsrv01.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/philologic/getobject.pl?c.296:1.toutvoltaire.34161.34182 [used 20-05-2015]. [ Links ]

Voltaire (J-M. A. dit). DSDP., 1750, Du sage et du people, in Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire tome xxiii. Paris: Armand-Aubreé, 1829. pp. 5-10. [ Links ]

Voltaire, 1756, Poem on the Lisbon disaster. Or: An examination of that axiom: 'All is well'. http://geophysics-old.tau.ac.il/personal/shmulik/LisbonEq-letters.htm. 3 pages. Consulted 09/25/12. Also Poème sur le désastre de Lisbon (1756). ATHENA, Pierre Perroud. http://athena.unige.ch/athena/voltaire/voltaire_desastre_lisbonne.html. Consulted 09/25/12 [ Links ]

Voltaire, 1763, On toleration. Tr. JM McCabe (1912). http://classicliberal.tripod.com/voltaire/toleration.html. 20 pages. Consulted 10/13/12. [ Links ]

Voltaire, 1764, Liberty of the press. Tr W Fleming (1901). http://classicliberal.tripod.com/voltaire/press.html. 2 pages. Consulted 05/23/12. [ Links ]

Voltaire (F-M Arouet), 1765, Dictionnaire philosophique portatif; Nouvelle édition. Londres. [ Links ]

Wiki, 2012a. File: Voltaire Philosophy of Newton frontispiece.jpg. Wikipedia Commons. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Voltaire_Philosophy-of_Newton-frontispiece.jpg. 4 pages. Consulted 10/09/12. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

J.J. (Ponti) Venter

Email: Ponti.venter@nwu.ac.za

15 Dec 2015

1 This article lies in the extension of three others about methodologies of targeting.

Venter JJ (Ponti), 2013a. Methodologies of targeting - Renaissance militarism attacking Christianity as weakness. Koers 78(2), doi: 10.4102/koers.vt8i2.62. http://koersjournal.org.za/index.php/koers/article/view/62 [There are no keywords in the articles themselves but the following terms may be helpful: Classicist, hermeneutic, heroic, exemplar, imperialist, Roman, competitiveness, balance of powers]

Venter JJ (Ponti), 2013b. Pragmatism attacking Christianity as weakness - methodologies of targeting. Koers 78(2), doi:10.4102/koers.v78i2.61 http://koersjournal.org.za/index.php/koers/article/view/61 [scientistic, method, polarize, Christianity, meekness, effective, solipsism]

Venter, J J (Ponti), 2015 - Methodologies of targeting - Neo-Classicist Voltaire's twisted hermeneutic for targeting 'criminal' Christinianity in Koers ****

2 Elemens and Neuton - at this stage French spelling was still a bit fluid. One can see this especially in the different spellings in different editions of the Dictionnaire portatif... in the 1760's.

3 Regarding Voltaire I have worked this idea out in an article on his five catechisms; the quote above is drawn from one of them. State control over religion and teaching the young is an Ancient Greek idea: this is why Socrates was put to death. This doctrine had been revived in the Renaissance by Machiavelli, expanded by Bodin and Hobbes, was intensified by the Enlightenment thinkers, even more so in Metaphysical Idealism (Hegel, Fichte) and found its summit in Communism, Fascism and Nazism. Kant's critical idealism may have been a exception - according to him the state's task was to allow for self-emancipation; it would be criminal if the state intervened to block this.

4 Even later Calvinists have over-accentuated the legislator aspect in CalvOne can find the following metaphors for aspects of God's relationship to the world on one single page: legislator, source of life, source of the good, guardian, protector, the faithful, merciful, father, lord, majesty, the glorious, judge, healer (cf. further Institutes, I, ii, 3).

5 Vico: "... until now the philosophers, contemplating divine providence only through the natural order, have only shown part of it. ... The philosophers have not yet contemplated His providence in respect of that part which is most proper to men, whose nature has this principal property: being social (Vico, SN, 1744: The idea . 1-2).

6 Like most of the Enlightenment thinkers, Quesnay believed that in order to live a life dignified of the Supreme Reason and Light, reason disclosed by education was necessary. "Without knowledge of the natural laws that have to serve as basis for legislation and rules of behaviour, there is no evidential understanding of the just and the unjust, of natural rights, of the physical and moral order, of the essential distinction between general and particular interests, of the real causes of the prosperity and decline of nations, of the essence of moral good and evil, or of the sacred rights of those who govern and the duties of those who have to obey. [Positive law is but the exposition of the natural laws most advantageous for the sovereign, thus also for the citizen] ... Where this is the case, it will be impossible to propose an unreasonable law, for both government and the citizens will soon discover the absurdity of this. This is especially true for the subsistence of the nation and the means to defend it: if the flame of reason enlightens the government, laws detrimental to society will soon be taken off the books (Quesnay, 1965:375-6)."

7 In his Exposito in Apocalipsim Joachim rewrote the Apocalyps as world history: God the Father in control ofthe Jews and Old Testament people being the sensory; the Christians of the New Testament being the rational ones under lordship of Christ; and the mystical intellectual elite would be the post-Church people of the New Jerusalem lorded by the Holy Spirit. Some elite groups (some Masonic lodges) adopted this view of history: their initiation process would then lead to the enlightening intellectual contact with the "divine". Lessing comes to mind; the librettist of Mozart's Zauberflöte; even the decadent outflows of the Golden Dawn, such as Aleister Crowley. Joachim of Fiore was much more influential than he is usually given credit for: he inspired Richard Lion Heart to undertake a crusade to liberate Jerusalem; also, according to recent research, Christopher Columbus to find a rpoute to the East, in order to convert the world in expectation of liberating Jerusalem (cf further

8 Cf. further Thomas Aquinas, SCG, I, 3, 2. Descartes says: ". but I have observed certain laws established in nature by God in such a manner and of which he has impressed on our minds such notions, that after we have reflected sufficiently upon these, we cannot doubt that they are accurately observed in all that exists ....(DM, **** V)??????"; Locke, EHU, III, iii, 14.

9 I am using "nomism" (from the Greek nomos = law) here, in distinction from "legalism", which has a more down-to-earth meaning.

10 Control not based upon some systematic explanation is often irresponsible; prediction of consequences within open systems is by and large limited or barely possible. The longer-run or wider unpredictability led to Pragmatism. Pragmatism has its roots in the mastery motif of scientism and positivism - it wants to master by experiment from situation to situation. The experiment, however, is seldom a representative micro-imitation of the open possibilities beyond it. Thus Pramatism becomes a never ending finding of means towards nearby ends that are actually also means. If one can sensibly talk about "post"-modernism, then one can say that the Modern origin, nature, and the Modern destiny, rational humankind, have both collapsed - nomadism is the outcome.

11 The elitism of the enlightened, however, changed the self-liberation into "decolonisation of the mind" by an elite "group consciousness" as found for example in the idea of a "class consciousness".

12 If established Christianity can learn anything from the Enlightenment, then it is to do continuous introspection about its power structures: the priesthood's own actions helped to create hatred against them. A "priest" who fornicates with the unbelievers is often still despised by his friends.

13 Auguste Comte and Karl Marx are to be understood in the extension of Kant's philosophy of history: the first more mystical and the second almost mystically collectivist.

14 Cf further Van denbossche (1974).

15 This is the order, construed over centuries, for training in the positivist method, according to Comte (Catéchisme positiviste, 1852:62).

16 The priesthood or clerics were the seen as the prime enemies of enlightenment and emancipation: one has but to read Kant's Was is Afklärung (1786) or Condorcet's Esquisse ... (1793-4). They were said to protect their power and privilege by subterfuge fear (the Inquisition!).

17 Mao tse-Tung's government changed the photographs and

18 It is thus not so surprising that some heterodox "Christian" philosophies of history - such as that of Lessing, Goethe and Teilhard de Chardin, shows these traits in the vorm of the divine coming out of itself into nature and in progressing through natural evolution returns to itself as the divine.

19 J J (Ponti) Venter - methodologies of targeting - Neo-Classicist Voltaire's twisted hermeneutic for targeting "criminal" Christianity. In Koers ****

20 J J (Ponti) Venter - Voltaire's satyrical catechisms - Secular confessionalism part 2 - soon to appear in Phronimon.

21 Decret de l'Assemblée National qui supprime les Ordres Religieux et Religieuses - Le Mardi 16 Fevr. 1690. Que ce jour est heureux mes Soeurs, oui les doux noms de mère et d'épouse est bien preférable à celui de noms - il vous rend tous les droits de la Nature ainsi qu' à nous.