Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Koers

On-line version ISSN 2304-8557

Print version ISSN 0023-270X

Koers (Online) vol.80 n.3 Pretoria 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.19108/koers.80.3.2238

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Methodologies of targeting - Neo-Classicist Voltaire's twisted hermeneutic for targeting 'criminal' Christianity

J J (Ponti) Venter

School of Basic Science North-West University (Vaal Triangle Campus) South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article is the third of four1 written to line up two extremes in the history of methodology: early 20th century Pragmatism and late-Renaissance militarism, filling in the middle period, focusing on Voltaire and the atmosphere before the French revolution. Pragmatist William James pretended to offer a purely formal method, yet strategized it as a doctrinal attack on the inefficiency of Christianity (according to his (mis)understanding of it). Machiavelli attacked Christianity's practice of justice and meekness as weakness, from his own Classicist, Romanist militaristic empire perspective. Voltaire, in middle Modernity, devised a hermeneutic from an Enlightenment position with a strong Neo-Classicist slant, by representing Ancient Classical tradition as fundamentally tolerant to difference of opinion, and by over-painting any suggestion that early Christians were persecuted for their faith. He represented the Christians of his own days (often rightly so) as unfair, criminal and violent, especially with regard to heterodox opinions. His naturalistic tendencies, contradicting his liberalism (an intolerant propagation of tolerance) must have contributed to the severity of persecution of non-compliant Christians during the 1789 Revolution. Later naturalistic liberalists, such as Dide and Booms, and several anti-Christian sites on the internet, found and find their inspiration (sometimes against his intentions) in Voltaire's criticism of Christianity.

Keywords: Apologetics, tolerance, Neo-Classicism, Vico, book, hermeneutics, practicalism, Nature, Reason, statism, peace

ABSTRAKTE

Hierdie artikel is die derde van vier, geskryf vanuit twee historiese ekstreme: vroeg-20e-eeuse Pragmatisme en laat-Renaissance militarisme. Dit vul die middelperiode in met artikels gefokus op Voltaire en die wysgerige konteks voor die Franse Rewolusie. Pragmatis William James het die pretensie van 'n suiwer formele metode voorgehou, maar dit strategies ingevul as 'n doktrinêre aanval op die oneffektiwiteit van die Christendom (volgens sy eie (wan-)verstaan daarvan). Machiavelli het die Christendom se beoefening van geregtigheid en sagmoedigheid as swakheid aangeval, uit sy eie Klassistiese, Romanistiese, militaristiese ryksperspektief. Voltaire, in middel-Moderniteit, het 'n hermeneutiek uit 'n Verligtingsperspektief ontwerp, sterk Neo-Klassisisties, deur die Antieke Klassieke tradisie as fundamenteel tolerant teenoor meningsverskil voor te stel en deur enige suggestie dat vroeë Christene oor hulle geloof vervolg is, toe te smeer. Tegelykertyd het hy die Christene van sy tyd (dikwels tereg) voorgestel as onregverdig, krimineel en gewelddadig, veral teenoor afwykende menings. Sy naturalistiese neigings, wat sy liberalisme weerspreek ('n intolerante propagering van toleransie), moes bygedra het tot die skrikwekkende vervolging van oninskiklike Christene gedurende die 1789 Rewolusie. Latere naturalistiese liberaliste, soos Dide en Booms en verskeie anti-Christelike blaaie op die internet, het hulle inspirasie gevind (soms teen sy intensie) in Voltaire se kritiek op die Christendom.

Sleutelwoorde: Apologetiek, toleransie/verdraagsaamheid, Neo-Klassisisme, Vico, boek, hermeneutiek, praktikalisme, Natuur, Rede, statisme, vrede

1 THE PROJECT

Voltaire, famous French Enlightenment philosophe and literary writer during the decades before the French Revolution, was quite vicious in his attacks on Christianity. According to him, Christians had been the most barbarous warmongers and killers, attacking people for no other reason than difference of opinion. They were but the heirs of Jewish barbarism.

1.1 Continuity in discontinuity

There are two sides to Voltaire's attack upon Christendom: interconnected but clearly distinguishable: his prejudicial reading of history and his admiration for recent scientific discoveries, especially the work of Newton. I shall focus on his historical hermeneutic first. Both sides of Voltaire's thought, like that of his contemporaries, are rooted in the Classical era, well-cooked into a Modern broth. The activities of different secret societies indicate a tendency to Ancient paganism in a vulgarized form. Voltaire and Sade shared this environment.

This article is the third in a series that can be described as presuppositional apologetics. The articles have grown out of a broader study of scholarly methodology. From a historical point of view, having studied a Renaissance thinker (Machiavelli) and a late Modern thinker (William James), one somehow 'connects' the lines, by also analysing a middle Modern (Enlightenment) thinker, using intermittent synchronic cuts to show the diachronic persistence of ideas, but also the shifts. The French Revolution of 1789 and its preparatory philosophes are known to have been anti-Christian, especially anti-Catholic. Among them Voltaire was a moderate, known for his tolerance - especially his struggle for freedom of opinion and expression.

Voltaire's methodology is very important, given his self-centred adoration of Newton's physics and method and the elite position he awarded himself in relation to a deified Newton. A further contributing factor here was Classicism's influence on methodology in the Renaissance (Machiavelli) and Neo-Classicism's during the Enlightenment; Neo-Classicism was an adaptation of Classicism; a Modernization of Renaissance Classicist cues. Voltaire's influence is still strong; one has but to Google 'Voltaire': large numbers of especially anti-Christian quotes from his works appear.

1.2 Relativism combined with formalism in Pragmatist emptiness

I am trying to specifically analyse today's strange tension between post-modern relativism and the absolutizing of form; that is, technical method. The absolutizing of technical method can be understood from the fact that our lives are largely embedded in technology, with its digitized format as the summit. Post-modern relativism does not totally reject formalism; one still needs normative standards for rating students, promoting members of staff, rating the standing of a company or a government department. The calculator becomes the judge and standard. Bureaucracy rules; the accountant is judge supreme. That is: based upon the belief that formal procedures are pure forms: they (supposedly) do not commit the judge to any belief whatsoever; prejudices are all eliminated by the packaging. In these articles I have attempted to question the ontological, ideological, cultural and religious neutrality of the formal sides of method. Since there are different forms, each form itself - as a particular form - must have a distinctive content. Heidegger says that Modernity is shackled by method-idolatry. Post-Modernism - even the work of the methodological anarchist, Feyerabend2 - safeguards its doctrinal relativism by adhering to form, thus remaining very 'Modern'.

Modern thinkers had a tendency (since Bacon and Machiavelli in the Renaissance) to 'certify' their doctrines by showing them to be the necessary result of a new, supreme method. James did so too: his way of illustrating the power of his method by attacking Christianity was part of this heritage. It somehow was the Modern remnant of the struggle between church and state and between scholarship and religion at large. One finds this in Machiavelli, Hobbes, in Kant, in Saint-Simon and Comte, in Marx - too many to name. This in itself shows a prejudice created by the continuous secularizing of Western humankind, based on the Modern belief in the "super-natural" abilities of humankind.

Secularising is of the essence here. There were opposing reasons for the attacks on Christianity. James viewed Christianity as simply too inefficient to give expression to and act on its own beliefs. But Machiavelli accused good Christians - using a method expressly designed to show a better way - as a hindrance to efficient policies: kindness, neighbourliness and justice do not work in politics (cf. further Machiavelli, Discorsi II, ii, 6 ff). In this he pre-empted Nietzsche (cf. Nietzsche: Zarathustra I: Vom Krieg und Kriegsvolke; 1930: 48ff). A peculiarity worth studying thus showed itself along the way: contradictory assessments of what is wrong with Christianity. This has a methodological basis that in turn is given direction by a world view.

William James viewed Christianity as a lost case - for all its pretence, it had not done any good in two thousand years. James' explicit aim was the establishment of a workable world view through his 'empty' method. Machiavelli recognized some good in Christianity, but this exactly is its weak spot, compared to Ancient blood-and-gore religions. Machiavelli was driven by a pagan militarism, based upon the Roman Empire ideal, and founded upon the deterministic pendulum cycle of history (cf. Venter, 2013c: I2ff).

1.3 Voltaire versus James and Machiavelli

Voltaire, however, was a man for freedom and free thought. His attack on Christianity was neither based on its goodness nor on its inefficiency, but exactly on its criminal aspects. On reading his analyses of Biblical narratives, it becomes clear that he, too, criticized from the perspective of 'nature', 'science', and 'reason'. The overlaps in ontological terminology - delivering contradictory results - indicate that methods are never purely empty and purely disinterested with regard to world view perspectives; also that world views' basic ideas do not completely overlap. It is thus important, reading backwards from the technical level, to enact some transcendental criticism to uncover the presuppositions in the undercarriage of the techniques.

From my own point of view, as an analyst, this required a loosening-up of my own categorical system in order to allow for the widest possible range. Only in this way can one see the reductionist attitude of Modern writers, who tended to hark back to Ancient oppositional categories, exactly in order to move away from Christian ideas. Thus the Christian agape was reduced to Ancient eros (sensual desire) - clearly already in Machiavelli and Hobbes, and expressly so in Feuerbach, Marx and Engels (cf. Marx & Engels, 2014). This was also the case in Voltaire (cf. DPP, s v amitié; amour).

1.4 The Neo-Classicist moments

Neo-Classicism contributed to more than only a secularizing of culture; in many respects it propagated a return to Ancient pagan ideas. Methodologically, it tended to say:

• Look how nice the Ancient intellectuals were, and how bad, untrustworthy, inefficient or criminal the Christian leaders are. My method shows you the better alternative.

• As Modern discourse matured, the Classical references were suppressed, but the 'idea'-logical tradition was sustained. A second important proposition - to be demonstrated here in the case of Voltaire - can be drawn:

• Methods and techniques are developed with aims in mind; aims imply norms and criteria. Methods may become techniques applicable in more situations than only those for which they have specifically been developed. But the burden of their original aims and the criteria behind these will move around with them. The form itself has content and this content is a doctrine.

Voltaire developed a method that had a normative base in Neo-Classicism, was aimed at being a critique of Christianity, not objective and wilfully prejudiced, Classicist in a normative sense: opposing the virtues of the Classical era to the crimes of Christianity. Form and content are fused by aims and criteria.

Historically the acceptable sides of his thought received more attention; much less has been written about the 'less holy' aspects. The selective intolerance of a man known for preaching tolerance itself was embedded in the way he read the Classical Roman era. The sustained naturalistic, antiChristian, Neo-Classicist structure of Voltaire's critique allowed others to radicalize his moderate liberal thought.

2 CHRISTIAN CRIMES AND ANTI-CHRISTIAN PROPAGANDA

Some pre-Revolutionary philosophes were socialists (such as Rousseau); others were liberalists, among these Voltaire. Both criticised Christianity; each from own perspective. Voltaire's more liberal critique was followed up in a moderate way by Kant; but some later liberals were quite fervent. The relevance of Voltaire can be seen in for example the extremist attacks by Auguste Dide at the beginning of the 20th century, but also still today by so many Voltaire excerpts, quoted (viciously) out of context. Auguste Dide, in a pre-preface to his work, The Christian legend (1914) summarized the crimes of Christianity against 'free thought' - 'free' being a normative adjective. The content of his arguments shows a contradiction of this norm.

2.1 The post-Voltaire case against Christianity

With a broad paintbrush and in broad strokes, Dide reminds us of the crimes the Catholic Church committed against heterodox scholars; of the Lutherans against the Anabaptists and the farmers; of the Enlightened Empress of Russia, Catherine the Great, being a Russian Orthodox monarch, for making laws against philosophy and Roman Catholicism; of Calvinism and John Calvin's responsibility for the execution of Servet and the doctrine of absolute servility to the state. Even Rousseau's utopian Masonic civil religion, requiring capital punishment for retracting one's acceptance of the state's civil religion, and the bloody terroristic execution of this doctrine by Robespierre, are blamed on Calvinism. Religion's instruments of power and its abuses are noted - and surely outrages happened:

[1] For sure, if ever religions have been armed against resistance and dominance, then it was the Christian Church. During the fifteen centuries they had at their disposal, the decisions to ban, the forfeiture and capital punishment, the extraordinary courts, the prisons, the cellar jails, torture in all forms, and cruelties, the scaffold and the stake ... (Dide, 1914:3).

2.2 The case against religion and against God

There is an alternative, though, in the words of Dide's Dutch translator, Booms:

[2] .that the readers will replace the meaningless believing without any proof with knowledge, or at least will make attempts to know by studying the Laws of Nature, the only true governor of the universe, and then according to the unchangeable and untouchable self-posed Laws of Cause and Effect, that have always existed, will exist in infinity, and which also exclude any divine intervention.

There is no God, no heaven, no hell; there is only Nature, unchangeably working according to cause and effect, creating, destroying, recreating, knowing no death, for what we call the end of life, is the transition to new action, to the generation of new life, the recreation, in eternal endless repetition (Booms, 1914: 13).

Dide believed in a purely physical universe. Turgot had already indicated the endless cycle of nature, but he retained a linear course for human history. Booms' naturalistic faith determines the totality of his approach to the world: one needs scientific knowledge to live and scientific knowledge is limited to knowing cause and effect and their 'self-imposed' laws. Note that Dide, right from the outset, begins to use the language of philosophical 'theology': 'self-posed Laws', 'unchangeable', 'creating', 'knowing no death' all the characteristics ascribed to 'god' by the Ancient Greeks and Medieval natural theologians. An important consequence of Modern subjectivist rationalism and the Modern interpretation of natural law is that the rational subject, the object, the divine, and nature had all imploded into but LAW by the time of Comte. These divine characteristics of 'natural law' cannot be derived from the facts of Physics, even though Mach and Einstein also believed in them. But Einstein expressly says: they are part of a presupposed world view. Given the power of this abstract Modern person baptized 'Science' and the magic of an expression like 'science says', Modern Naturalism always found it quite easy to propagate a divine physicalist law.

Yet blaming the Catholics, the Protestants, the Russian Orthodox, in fact all Christians, for atrocities, requires more than a purely physicalist world view. It requires moral criteria -Dide shouts them from the 'roof':

[3] There is no God!!... There can be no God!!...

Only Nature governs the universe and Nature continues her work without adoration or being-flattered; it shows humankind and all that exists the road to mutual utility and mutual support.

This is the morality of Nature!!! It does not want any adoration for it does not give any favours and knows no mercy and no compassion; it works according to rules of cause and effect established by the necessity for all eternity!! (Dide, 1914: 284 - his italics).

Note the italics, exclamation marks, the capitals. In the preface it is explicitly stated that Dide's work was a piece of responsible science, good for the propaganda campaign of free thinking. Voltaire himself was not an atheist: he rather espoused a panto-deism in which the divine was collapsed into the laws of nature, as is clear from his poem: Le desastre de Lisbon (1756). But this kind of panto-deism operates with a paralysed god; in practice 'nature' governs. Dide-and-Booms may have stretched Voltaire's ideas, but these ideas are implicit in much of what he stood for. Being propagandists, they followed him in his totally skewed representation of history: Robespierre, Nietzsche, and Modern patriotism surely had secular roots.

2.3 Whatever happened to free thought?

Booms, Dide's translator, describes himself on the title page as 'Vice-President of the International Propaganda Committee for the Application of Morality based on the Laws of Nature'. This is an almost mystical naturalistic metaphysics: 'Nature' appears as an active 'person' operating in terms of the laws of cause and effect - exactly what Auguste Comte rejected as (out-progressed) 'metaphysics' (Comte, 1852, preface). Booms and Dide knew for 'sure' that 'Nature' was in control; and also for how long: from all eternity to all eternity.

They made a double claim:

(a) their view is good science and

(b) it provides the right propaganda for free thought.

Propaganda it clearly is - but science? They knew for sure that in all history of humankind, the Christians alone have had the instruments of power to commit such atrocities. But how to know all this for sure? For sure - quite Modern - they stood in a divine Archimedean point, providing an overview over all of history - from somewhere in the eternal past to -somewhere in the eternal future.

The consequences of Dide's view: 'Nature' unavoidably (causally) teaches us - i.e. unwittingly coerces us into - 'utility' and 'mutual support'. Thus 'Nature' puts some people in power; they cannot - in mutuality - be but as merciless as 'Nature' itself! (Reductio ad absurdum). Perplexing: Christianity is blamed for the way in which merciless Nature deterministically controlled Christianity for everybody's advantage. When the scholarly charge sheet is an anti-Christian propaganda sheet, calling the 'other' utterly stupid, fraudulent, hypocritical, the claim of good scholarship fades away; fairness in weighing the evidence too.

3 VOLTAIRE AND DIDE-&-BOOMS

The authors of The Christian legend took their cue from Voltaire as pre-Revolutionary French satirist. He did find Christians -especially Catholics, in particular the Jesuits - to be fraudulent, hypocritical and murderous.

3.1 'From and through and to ... nature'?

And humanity then? Like Dide-&-Booms, Voltaire approached issues from the 'natural' side. 'Natural', here, means Modernity's 'natural': the mechanical, the biotic, the sensual, the emotional -that is: all the sub-rational functions (with an ambiguity: the Medieval creational 'natural' alloyed in). This made it difficult for Voltaire to find a distinctive characteristic for the human being. The clearest examples of this are his inscriptions on 'love' and 'pederasty' in the Dictionnaire ... (1765; s v Amour, Pederastie) and his sensualist struggles at the beginning of the Traite de metaphysique (TM, 1734: par I-II).

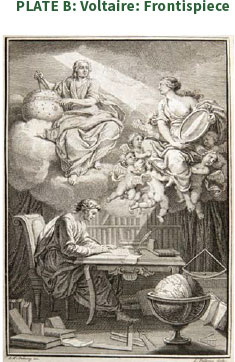

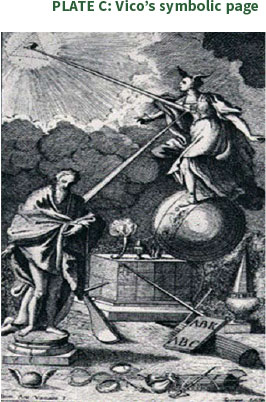

The Cartesian ambiguous belief in scientific control of nature (while being controlled by nature) was shared between Voltaire and Dide-&-Booms (cf. Descartes, 1969:143 ff).There was, however, also a serious difference between Voltaire (and before him, Vico) on the one hand and Dide-&-Booms on the other: Voltaire wrote during the early Enlightenment period: science to him was the light that could bring control over the phenomena of nature. Giambattista Vico (16681744) distinguished quite clearly between 'nature' as the socio-practical (rational) and 'nature' as the sub-rational. Voltaire does not refer to Vico, but Vico was in the air (read for example Turgot and Comte). In an unsystematic and more naturalistic way, Voltaire still attempted to work with Vico's distinction. Being an Enlightenment Humanist Voltaire focused on the practicalities of the relationship between thought and external reality, but his naturalistic base constantly interned him in the Newtonian model of natural science (cf. PLATE B below).

Led by this model he developed a scholarly method to target Christianity, following a road very similar, yet also dissimilar, to that of Machiavelli (cf. Venter, 2013c). Voltaire highlighted the goodness of the Ancient Classical people versus the badness of contemporary Christians; Machiavelli praised the (morally doubtful) military strategies of the Ancient people and highlighted the badness of the goody-two-shoes Christians of his days.

The International Propaganda Committee for the Application of Morality based upon the Laws of Nature, belonged to the late-Enlightenment overlapping with early Irrationalism: their logo still shows the torch of univers-al knowledge reaching to the globe and the Zodiac (as a physical universal), above the broken stone tables of the ten commandments. A living natural foundation constantly transforming itself is symbolized by the butterfly below (see Plate A).

The enigma of organic vis-à-vis the inorganic recurrently seems to create havoc for materialists. Is life in matter or does the inorganic create the organic? (J.C. Smuts, a contemporary of translator Booms, would argue that organised wholes allow higher level organised wholes to come forth (cf. Smuts, 1929: 1932).

Materialists want us all to subject ourselves to the merciless laws of nature, and be 'useful' to and 'supportive' of one another. But how to understand what this living-dead, Nature, wants from us? Reading Plate A from below, one has the impression

- something often conversational among 'objectivist' scientists

- that Nature 'speaks': it almost automatically creates the light of scientific knowledge in and for us - breaking through and shattering the stone table of the Ten Commandments. But why exert yourself to understand that speech, if one is merely an object of nature's laws?

3.2 Masters of the universe?

There is something special about the frequent appearance of the Zodiac in pictures like these - it presupposes a hidden Archimedean point and expresses the Modern motif of mastery -human masters of the universe.

Note the Zodiac's position in Plates B (Voltaire) and C (Vico).

- In C Maiden Metaphysics is standing on the Zodiac, with all the religious, natural and cultural symbols below her feet. Vico was an 'Alexandrine Patristic' (working from mystical metaphysical insight to the divine archetypes for culture and civil society), yet also Modern in the form of his belief in human control: a rational control of the universe. But he distinguished clearly between control of the physical and of the social.

- Plate B was published just a little later than C; it is located in physical nature, showing the scientist Newton in a divine position, controlling by measuring.

- Plate A still uses the Zodiac as Parmenidean Anangkê (Necessity) binding the universe, but even though its naturalistic propaganda is more fervent, the belief in a total human control of nature (Descartes) seems to have subsided somewhat: Dame Nature had become quite bossy.

- However, in all three cases there seems to be a hidden Archimedean point that provides this univers-al overview, presenting the 'universal' as mechanical or as bio-physical-wholeness. Vico appears to have followed the Cartesian cue of pulleying God into reason, thus giving science a divine, revelatory character. In Voltaire (and Dide-&-Booms) the suggestion of science as revelatory - the Greek Parmenidean idea of 'being' as 'uncovered-truth' - has been maintained, but the dependence on a transcendent (as acknowledged by Vico), has disappeared. Or, stated differently, divine truth is 'nature' and 'nature' is revealed in and by scientific reason (and mastered by reason) as the humanistic supernatural. In the Biblical idea of truth, the dependence on and the trustworthiness of God are upfront; thus creational revelation is actually but a medium (although in Platonist Christians such as Vico it directly expresses the archetypes) (cf. further also Paul's Letter to the Romans, chapter 1).

Plate B is the frontispiece in Voltaire's Elements die philosophie de Neuton; check Plate C that of Vico's Scienca nuova. Plate C appeared about 25 years before Plate B. In Plate B Newton is seen measuring the globe. Emily du Chatelet, Voltaire's life companion, represented as a Muse reflecting the divine light, and Voltaire in Caesarist habit the announcing scientist below. In Vico, the divine providential eye as the Platonist light source, casts its light via dame Metaphysics onto Ancient history (Homeros) - the source of social natural law, while she is standing on the universe (the source of physical natural law).

As in so many Irrationalistic 20th-century thinkers, the 'humanism' of Dide-&-Booms was but fingertips hooked onto a rock above the precipice of nature (whoever the person, 'Nature', may be). They became Hobbesians without the latter's controlling raison de l´état; for reason (including justice and mutuality through exchange) supposedly either mechanically cared for itself (read the economists) or had already gone to the grave in Nietzsche. Even the supernatural-from-the-natural, the Nietzschean Übermensch (with its Cartesian and Kantian predecessors), had its head knocked back into the natural neck. They do what according to Feyerabend 'all' scientists were doing anyway: play propagandistic power games (cf. Feyerabend, 1975: ch. 1).

4 VOLTAIRE: A METHOD OF TARGETING THE 'INFAMOUS'

[4] You fear books, as certain small cantons fear violins. Let us read and let us dance - these two amusements will never do any harm to the world (1764: 1-2).

Thus sayeth Voltaire (1694-1778) to the princes, and particularly the Catholic Church of France, in his essay on Liberty of the press (1764). The light-hearted style - almost Nietzschean - of the quote may mislead us about the very serious intentions, taking issue with the coalition between Church hierarchy and nobility, but especially with the former. They would easily commit judicial murder for some minor or absurd point of doctrine. He loved to cite the cases of Father Vannini (judicially executed apparently for having won too many theological disputes) and the Calvinist, Jean Calais (superstitiously executed and his family dispersed, since he supposedly hanged his own son to prevent him becoming Catholic). It is significant that these critics focus on these (argument-suitable) cases like Vannini, Calais, Servet, Bruno and others. Admittedly, though, these were not the only cases - remember the witch hunts. Voltaire himself had to spend time in the Bastille for having stepped on, or satirized, sore corns - but: he developed a methodological prejudice of prejudiced methodology for a sustained attack on Christianity.

4.1 Freedom of opinion and expression

In On liberty of the press he argues that it had not been Luther, Calvin or Zwingli's books that ruined the Catholic Church in half of Europe, but the fact that 'these people and their adherents ran from town to town, from house to house, exciting women, and were maintained by princes'. Some dumb, ignorant, vehement Capuchin monk on foot 'preaching, confessing, communicating, caballing, will sooner overthrow a province than a hundred authors can enlighten it'.

[5] It was not the Koran which caused Mahomet to succeed: it was Mahomet who caused the success of the Koran.

No! Rome was not vanquished by books; it became so by having caused Europe to revolt against its rapacity; by the public sale of indulgences; for having insulted men, and wishing to govern them like domestic animals; for having abused its power to such an extent that it is astonishing a single village remains to it. Henry VIII, Elizabeth, the duke of Saxe, the landgrave of Hesse, the princes of Orange, the Condés and Colignys, have done all, and books nothing. Trumpets have never gained battles, nor caused any walls to fall except those of Jericho (1764: 1-2).

Voltaire understood the issues of power involved here a bit better than did Dide-&-Dooms; also the way in which short term communication works. He also knew, given his own and his contemporaries' fondness of Ancient ideas, that the pen (book) surely is mightier than the sword in the longer term: one has to teach the 'Capuchin' something and make sure his memory is supported by notes of some kind before sending him into the province. Importantly - and he ignores this - it is quite difficult to control the pen's message, for unlike the sword it can be separated from its author and used (or abused) for unintended purposes. Yet he chose to ignore it all when it suited his methodological purposes.

Roman Catholicism was Voltaire's main target. In signing his letters with Ecrasez Y Infame ('Smash the Infamous') he first and foremost had the Catholic Church in mind. (But he viewed all religious wars as barbarism, including fanatic Calvinist reactions to murderous attacks from Catholics.)

4.2 Hermeneutics with an ideological twist

The issue of religious wars was crucial for developing a method to criticize Christianity:

[6] I think the best way to fall on the infamous ... is to seem to have no wish to attack it;

[1] to disentangle a little chaos of antiquity; -

[2] to try to make these things rather interesting: -

[3] to make ancient history as agreeable as possible; -

[4] to show how much we have been misled in all things; -

[5] to demonstrate how much is modern in all things thought to be ancient, -

[6] and how ridiculous are many things alleged to be respectable;

and to let the reader draw his own conclusions (Herrich, 1985, quoted from the larger Dictionnaire philosophique).

Although a 'political' ploy, Voltaire propagated this as a scholarly method (Neo-Classicism), to enlighten the people against the darkness of religion - a subversive Neo-Classicism as method.

As a scholar he consistently practised all 6 points of this methodology in an integrated way - one has but to read through the 'pocket-size' Dictionnaire philosophique portatif to see this in action. He appears ideological: methodologically taking the position that the end justifies the means (as did Machiavelli before him and William James later). This (supposedly) was admissible where it concerned the infamous Catholic Church: mislead the reader a bit by 'disentangling chaos' in the Ancient sources and make them agreeable by presenting their 'Modernity'. This means: consciously suppressing the worst aspects of Ancient practice and highlighting the worst aspects of the 'infamous'. How did some predecessors fare?

• Bacon with his mixture of Christianity and utopian Humanism knew Ancient thought quite well, but did not give it complete social authority.

• Descartes with his attempted totally new beginning ignored his own rootedness in it via the Scholasticism which he so despised, i.e. he copied from the Scholastic Christians without acknowledgement, while denigrating their work.

• Vico set a Modern example of using original Ancient documents in a goal-directed way, but he did not use them as a means of targeting. He tried to show how God, in spite of all deviations of sinful humankind, still governs the world towards a better deal.

• Voltaire provided Modernity with a techno-scientific mask, yet tried to find foundations in Classical 'light'.

Historical facts would make me a liar if I tried to cover up institutional religion's crimes, especially those of entrenched power cabals in its midst. These have been there for own advantage and would (and will) go to great lengths, even crime, to hold onto privilege. Arrogant and intolerant they were and still are. Voltaire rightly pointed this out. Also: he did not propagate violence, rather proposing tolerance in the form of allowing all ideas to compete, however despicable they might be.

Yet judging by his own words and his activism in writing, he had the make-up, and fluid (quasi pragmatist), morality of an ideologue. This certainly contributed to the later uncontrollable gulf of Hobbesian elitism of the Revolutionaries: enforced secularism, an anti-religious attitude, bloodshed simply because people carried the wrong surnames, mass bloodshed in the name of a cause, and so forth. Liberal Voltaire lamented the bloodshed brought about by the Christians; some 150 years later Mussolini would similarly frown at secular Liberalism: 'Never has any religion claimed so cruel a sacrifice from its members' (1938, II, 9; my bold). And we are still crying about the outcome of Modernity in the crimes of two World Wars.

As we can see in the cases of the Balkans, Israel, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, North Korea, China, Zimbabwe, Ukraine: now in late-Modernity1 all wars are world wars: like burning coal mines the smoke columns on the surface are localized, but underground the burning tunnels are all connected in a Foucaultian war network.

4.3 Enlightenment practicalism - method, knowledge, power

Voltaire, like so many 'enlightened' writers of his time, was neither an anarchist nor an atheist. There was a direct connection between his religious views, his political stance, and his method of critique.

He believed in enlightened monarchy - since Vico is seen as the very summit of historical en-lighten-ment (cf. Vico, 1984, SN, II, ix, 947 ff); Kant, Was ist Aufklärung, 2012: 60 ff). He thus maintained correspondence with Catherine the Great of Russia, and on and off with Frederick of Prussia. The fact that he had repeated fallouts with the latter (a critic, yet secret follower, of Machiavelli), at whose court he took refuge from the French monarchy, should have warned him

• that 'knowledge' is not 'wisdom' and does not guarantee 'virtue' - as Enlightenment practicalism believed (holding on to Socrates, Plato and Aristotle);

• that secular 'enlightenment' does not heal the dark side of having too much power; and might even be as dangerous as religious elitism, or pretended religious righteousness;

• that possessing institutionalized power is not the same as believing in the foundational doctrines of the relevant institution.

His very own methodological manipulations (quote [6]) should have indicated that the more the power, the greater the possibility of conceptual and practical manipulations. Doctrine often follows power - as rationalization or justification (as Mussolini actually admitted; cf. 1938: 1 ff)).

4.4 Progress: from Nature as origin to Reason as finality

Religiously Voltaire was a panto-deist trusting in 'reason'. Through all of the Enlightenment some forms of the Ancient and Medieval doctrines of 'natural law' have all too often been presented (in a twisted form) as the Biblical idea of God's law (providence) given in the human heart - the heart then presented as some sub-rational (instinctive or - at best -sentimental) proclivity (cf. Turgot, 1973: 71). Voltaire claimed that a violent atheist is more dangerous than a violent Christian, but he viewed a violent religious fanatic as much more dangerous than a morally paralysed philosophical atheist, such as the Roman senate in Cicero and Caesar's days (1763: 8). Rational philosophy, even if atheist [supposedly], was safely tolerant - yet it was the adorers of reason who committed the most violent crimes during the first French Revolution some 20-30 years later.

Since Machiavelli, Descartes and Hobbes, Modernity had been pestered by a serious difficulty. Onto-logically, its method was energized

• on the one hand from its doctrine of the arché (its causa efficiens): reduced Nature,

• but on the other by its telos (causa finalis): Reason (or the Intellect controlling reason by Intuition).

Intellect and Reason thus became the new supernatural. But after Hobbes the issue of 'rationality' had already become a serious concern. Hobbes presented the worst of the sub-rational (the instinctive striving for power, honour, and glory at any cost) as the natural state of being human. He located the 'rational' in the absolute, totalitarian state (allowing the individual only some quiet moments of rationality). This hidden irrational drive was adopted into all the serious philosophies of progress, as the motor moving history forward. Before the later Comte, Dilthey and Husserl, the issue of human life had widely been presented as survival against the odds of inter-individual human terrorism.

Voltaire himself struggled to find a balance between the individual's natural needs and his propagation of tolerance - see his hilarious inscription, 'self-love' (amour propre), in the Dictionnaire philosophique portatif. His arguments about freedom and tolerance concerned freedom of religion, expression, thought, i.e. the 'higher' freedoms. Regarding the sub-rational (survival) animosities among humans, the only antidote apparently available (until individual enlightenment at least had disclosed the social passions), was the rational civil state, whose task it was protect one citizen against the other (in Hobbes also against the other powerful institution: the Church). Anarchy was unaffordable. Yet, as Kant - two decades after Voltaire - succinctly formulated it:

[7] The difficulty ... is this: if he lives among others of his own species, man is an animal who needs a master. For he certainly abuses his freedom in relation to others of his own kind. And even though, as a rational creature, he desires a law to impose limits on the freedom of all, he is still misled by his self-seeking animal inclinations into exempting himself from the law where he can. He thus requires a master to break his self-will and force him to obey a universally valid will under which everyone can be free. But where is he to find such a master? Nowhere else but in the human species. But this master will also be an animal who needs a master. Thus while man may try as he will, it is hard to see how he can obtain for public justice a supreme authority in a single person or in a group of many persons selected for this purpose. For each one of them will always misuse his freedom if he does not have anyone above him to apply force to him as the laws should require it. Yet the highest authority has to be just in itself and yet also be a man. ... a perfect solution is impossible. Nature only requires of us that we should approximate the idea (1975a: 46 - sixth proposition; translated by author).

Kant wrote these words in 1784, just more than four years before the French Revolution's Declaration of the rights of the human and the citizen. His point is quite simple: regardless of whether we have a have a general will as law in a democratic format or in the form of enlightened monarchy, the 'rational' will always be undermined by the 'animal'. A just sovereign needs to have Medieval divine characteristics, but speaking from a Humanistic perspective, still be a human being. Kant remained ambiguous here: in his 1786 essay Conjectures on the beginning of human history, a naturalist-deist, rationalist commentary of the Biblical Genesis, he makes nature (instinct) the voice of God, but also views the human being, as rational being, as elevated above nature to equality with the divine (1975b: 87 ff.). Thus he could argue for en-lighten-ment to be a self-educating, bottom-up process, while sustaining an enlightened monarchy as the best form of government. Finally his historicized ontology becomes governed by the rational idea as telos (to be approximated), under the causal control of the perpetual conflict processes of nature-seeking-equilibrium. Where have all the freedom-flowers gone?

Kant posed the dilemma of his day - a dilemma suppressed in Voltaire's methodology. Voltaire trusted the scholarly elite to provide enlightenment through (correct) knowledge - thus publishing a pocket-sized Dictionnaire philosophique portatif (1764-5) as a more efficient enlightenment instrument than the voluminous (too materialist and atheist) Encyclopédie Ïrancaise (edited by Diderot and D'Alembert). This Dictionnaire ... is a world-and-life-view document intended for popular instruction, having many articles about Biblical figures, saints, and moral issues, and is slanted in favour of Greek and Roman Classics (versus Ancient Jews and Christians as well as Voltaire's contemporary Christians). Ontologically it becomes a natural history extended into a human history.

4.5 Neo-Classicism and method

The issue here remains method and scholarship. Scholarly methods are forms of (non-scholarly) power; they may become very powerful instruments beyond scholarship, for they could become the cultic parts of an ideologized belief in 'science'. Voltaire, like almost every Enlightenment thinker, was a Neo-Classicist. I have argued elsewhere that one finds two kinds of Classicism:

Renaissance Classicism used the (Western) Classical Ancient (Greece and Rome) as sources of information, models and methods, while

Enlightenment Neo-Classicism used it as source of models, but derived its information and methods from Modern science (or at least pretended the latter). (Cf. further Venter, 2013c.)

Voltaire stretched the rules a bit: he wilfully polished the Ancient as models, making sure that the 'infame' appears in a very bad light next to it. His 1763 essay On toleration (a topic he repeatedly wrote about) is construed to show (i) that fanaticism reigns in credulous religion, but (ii) that philosophy, 'the sister of religion', enlightens and serves mildness: where philosophy reigned, in Ancient Greece and Rome, there were no religious persecutions. This essay encompasses most other writings of Voltaire on the topic; I shall more or less follow its argument in my analysis.

He wrote the essay to beg the king to allow Huguenot exiles back into France, arguing that they posed no threat, asked no special favours, and would contribute to the social well-being of the country. Writing extensively on the outrages committed by Christian religion, he provides examples from Turkey, England, some American states, of the brotherhood of people of different religions. But he overstated his case: the supposed Islamic religious tolerance by Turkish rulers was obviously not true. This shows the ease with which he turned his own prejudices into 'facts'.

4.6 Cleansing the classics with 'nature' as soap

However, his analyses of tolerance in Ancient times - both here and in his Dictionnaire (s v Athée, Atheïsme), are particularly slanted. He misconceived the relationship between religion and politics in an Ancient totalitarian state; he appears not to have wondered about the changes in divine hierarchies whenever one kingdom or empire overran another. Given the tribal total unity of cult, culture, politics, the economy, and so forth, all ancient wars were 'religious'. Rousseau saw this: 'The political wars are also theological wars,' he says (The social contract, IV, viii). This tribal conception of the divine and of society remained alive until quite late - it is still to be found in the specifically anti-Christian logician-cum-occultist Apuleias of Madaura (114-184 a. D.). Voltaire tends to ascribe events of religious persecution, such as the execution of Socrates, in terms of economic and power interests rather than religion.

[8] A French writer, attempting to justify the massacre of St Bartholomew, quotes the war of the Phocaeans, known as the sacred war, as if this war had been inspired by cult, dogma, or theological argument. Nay, it was a question only of determining to whom a certain field belonged; it is the subject of all wars. Beards of corn are not a symbol of faith; no Greek town ever went to war for opinions. What, indeed, would this gentleman have? Would he have us enter upon a 'sacred war'? (1763: 8). 3

The subject of every war is but a piece of land? Of course such an explanation is not entirely incorrect. Yet in its one-sidedness it belies the fact that to have Socrates condemned, his accusers had to convince a large congregation of 'judges' of his 'atheism'. In such a courtroom the accusation of atheism held water, since the said power and economic relationships were part of an original unity with other aspects of human life; importantly the cultic and the transfer of tradition (education).

Voltaire himself characterized the execution of Socrates as the most odious event in the history of Ancient Greece (DPP, s.v. Athée). One also wonders why Voltaire did not see similar possibilities (economic interests) where Christians had been involved in religious wars: why absolve pagans in this manner, but not Christians?

Machiavellian Classicism implied the very opposite of Voltaire's view of the relationship between war and religion in Ancient times: Machiavelli praised exactly the Ancients' fierceness and their (ab)use of religion for political ends. This could, hermeneutically, not work for Voltaire, who wanted to paint an opposite picture. Given his aims, he had to give a different explanation for Ancient bloodshed. The (quasi Hobbesian) natural inclinations of humankind provide easy explanations: jealousy, power mongering, fighting for food and land - but NEVER religion. His ontology provided him with a dialectical framework to explain the historical issues away, after the fact. Voltaire and Machiavelli followed similar selective methods: they just selected different data; or they read the selected data in a very slanted way. In his hermeneutics, Voltaire was as naturalistic as Machiavelli. But if nature controls culture everywhere; where is reason?

In terms of Voltaire's ontological framework, the early Christian persecution by the Roman Empire then had everything to do with inter-sectarian power mongering by the Jews; the Romans supposedly doing their best to protect Christians. Nero's persecution was then solely based on a malicious lie: that Christians had burnt down Rome (1763: 8-9). Why then this lie?

Voltaire sensed the existence of counter-examples. Instead of seriously considering them as falsifiers of his theory, he continued his strategy of explaining them away by finding other reasons, or having the whole context displaced by a partial (correct 'as such') reason. The history of the martyrs was simply too overwhelming to ignore, thus:

[9] There were Christian martyrs in later years. It is very difficult to discover the precise grounds on which they were condemned; but I venture to think that none of them were put death on religious grounds under the early emperors. All religions were tolerated ... Titus, Trajan, the Antonines and Decius were not barbarians. How can they suppose that they deprived the Christians alone of a liberty which the whole empire enjoyed? How could they venture to charge the Christians with their secret mysteries when the mysteries of Isis, Mithra, and the Syrian goddess, all alien to the Roman cult, were freely permitted? There must have been other reasons for persecution. Possibly certain special animosities, supported by reasons of state, led to the shedding of Christian blood (1763: 9).

Having de-contextualized the events, Voltaire could re-contextualize them in his own way. He refers to actions of Christians provoking persecution; actions of Protestants (such as Farel) who supposedly 'deserved the death which he managed to evade by flight' (1763: 9). Though in other contexts he blames the crimes of the Roman Catholic hierarchy for the spread of Protestantism, suddenly here the great preacher of tolerance judges a mild act of resistance (compared to the violent oppression that provoked it), as deserving death?

4.7 Caesarism: 'reason of state'

Voltaire keeps quiet about a deeply religious reason for the resistance of early Christians: Caesarism. Caesarism - probably inherited from Egyptian Pharaoism - viewed the head of state or the sovereign as a ruling god. The sovereign may be, as Kant said (quote [7]) a democratically elected one or a hereditary monarch. Voltaire discursively recognizes the issue but hides it behind the abstraction, 'possibly certain animosities, supported by reasons of state' (quote [9]). 'Reason of state', since Hobbes, meant no more than the policies and actions of a holistic, totalitarian, absolute (i.e. 'divine') state, as moderator of the basic animosities among individuals and 'civil' institutions (cf. Venter, 1996:175 ff.).

Furthermore, in a polytheistic society, one divinity more, or one less, makes little difference to everyday life. But a religion that recognizes only a single god, different from everything else and upon which everything else depends, could not accept another human being as god; not even pragmatically for the sake of 'reasons of state'. 'Reason of the state-as-god' could, among Christians, never be an argument for unqualified obedience. In the 18th century context of quasi-cultic secret societies (Voltaire himself belonged to an exclusive rationalist pagan 'Temple', a Graeco-Roman kind of denominational ecumenism developed while sustaining the adoration of the civil state as (higher) reason (Hobbes: 'Leviathan' is the earthly God'; cf. 1946: II, 17).

Voltaire, accepting abstract, empty 'reasons of state' as 'explanation' of judicial violence, could thus not see a religious factor in martyrdom (in fact mass murder). He twisted his method into a dialectic: while pleading for religious tolerance on the basis of the common good, he denies that a Classical absolute state could itself become a 'jealous god'.

4.8 Civil religion and nationalism

Voltaire's contemporary with whom he corresponded, Rousseau, fellow Neo-Classicist and fellow proponent of religious tolerance, in Du contrat social (IV, viii) prescribes capital punishment for only one offence: not adhering to the god the state adheres to (in the words of Socrates' accusers). Rousseau's problem with Christians was that if they were not coerced into signing the state's 'Masonic' confession, they would become a divisive factor; anti-patriotic or weaklings uncaring for the fatherland. The 'general will' had to force citizens to be free, that is, into obedience of the 'general will'. Rousseau's patriotism was/ is no less intolerant than any other form idolatry.

Voltaire could surely have noted the implicit intolerance of a Rationalist, ecumenist, civil religion in his direct environment, even though he was nearer to Lockean liberalism than to Rousseau's socialism. He methodically overlooked the clear facts of Ancient and contemporary history, simply because he had pre-purified his 'facts' of any religious significance.

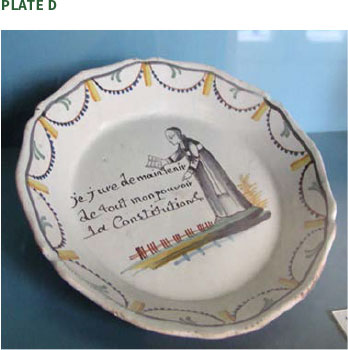

The Civil constitution of the clergy of the French Revolutionary parliament, a few decades later, followed Voltaire's and Rousseau's ecumenist '(in)tolerance'. This law limited all religious authority to the political boundaries (national and local), and also subjected officials of the dominant (Roman Catholic) Church to the civil authorities within these boundaries. They were not allowed to appear in public with noticeable indications of their religion. All church officials had to be elected by vote, the (civil) citizens of the relevant region being the electorate, elections being organized and supervised by the civil authorities of the region. The clergy had to take an oath in terms of this 'Constitution':

[10] in the presence of municipal officers, of the people and the clericals, the oath to be loyal to the nation, the law and the king, and to support with all his power the constitution decreed by the National Assembly and accepted by the king (Civil constitution, Title II, article 23; cf. 2012: 2).

Note the words singled out in the commemorative plate [D]: 'I swear to maintain with all my might the Constitution'. It is significant that specifically this article has been singled out for the clergy's oath. It is the article that sets the state above the church in structure and management; it is the Ancient Roman and Greek idea of the relationship between religion and state; it is the Machiavellian one; it is the Hobbesian one.

At this stage of the Revolution the pope was still recognized as the leader of doctrine; but the Deist 'Supreme Being' of Thomas More and Rousseau had already been introduced in the Declaration des droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen of 1789. Somewhat later Robespierre would act as 'Supreme Pontiff' to introduce its cult during a reign of terror seldom seen. Monseigneur Boisgelin, the archbishop of Aix, noted in response that 'JesusChrist gave his apostles and their successors the mission for the salvation of the faithful; He did not give this, neither to the magistrates nor to the king' (Hocking, 2014:94 ff.). Boisgelin, being Catholic, may have reduced Christianity to the institutional church, but he did see correctly that Christianity could not simply adopt the kind of religion prescribed by the state, i.e. a pagan kind of totalitarianism.

Voltaire, blindfolding himself to the dangers of statism and Caesarism and naturalistically arguing away all semblance of a deification of something 'this-worldly' (with its violent religious consequences) -while on the one hand struggling for liberty of religion, opinion, the press, precisely this man, on the other hand, became so obsessed with the wrongs of some that he could no longer fathom the basis of such wrongs, present also in those he admired. This is revolutionary historiography; history rewritten to suit an ideological purpose.

He may not have advocated an absolute and totalitarian state as such; but he appears to have accepted a tolerant, enlightened, totalitarian state, based upon the belief in education by scientific enlightenment. He too easily explained all of non-deist religion as primitive credulity. In his Newton frontispiece (Plate C below), Classical symbols of power are Modernised into symbols of scientific enlightenment.

Today he would surely have been labelled an Anti-Semite and Islamophobe (see his inscription s v Abraham in the Dictionnaire ... portatif), as a racist and a cultural racist, and as a homophobe (to a certain extent). The symbolism of power plus intellect would recur in all fierceness and maximally intolerant during the Revolution (the fasces and the spears are presented together with Philosophy in Revolutionary emblems and symbols). Yet present-day critiques of Christianity often sound like that of Voltaire and Rousseau.

5 REVIEW AND PERSPECTIVE

In 1769 Voltaire wrote his own essay on a theme that resurfaced from time to time since the letters of Cristin de Pizan in the 14th century: that of universal peace or even 'eternal peace'. Cristin de Pizan was motivated by her Christian faith. The Abbot of Saint-Pierre also propagated this: in fact he believed that one could convince the nations of Europe that it is in every nation's self-interest to punish any instigator of war; he proposed a kind of European government to ensure control. In 1796 Kant, though rejecting both Saint-Pierre's and Rousseau's versions of the project of universal peace, shows echoes of this in his argument that finally a covenant of nations will exert such control. This, however, would come about as the outcome of conflict and competition: the final balance of powers (cf. further Zum ewigen Frieden, 1975: 193 ff).

Voltaire ridiculed this. He argued that controlling war was not the answer - rather he quietly followed Locke in propagating toleration. Locke - in his Essay on toleration (1666) had no such universal political consequences in mind; he simply argued that it was unchristian and irrational to persecute somebody for his faith. In Voltaire's essay, Pour la paix perpetuelle, par le docteur Goodheart, traduction de M Chambon (1769) he still insists that it is Christian intolerance - inherited from the Jews, who inherited it from the Egyptians - that causes injustice. Wherever there is a priest, there is intolerance, murder, and war (see Pour la paix perpetuelle, paragraphs V ff.). Machiavelli had already argued that wherever the Pope goes, there is division in the state; Rousseau said something similar. Both therefore looked to the Classics, and decided (as did Hobbes) that state control over religion was necessary. However, they did not specifically have intolerance about doctrine in mind: they rather saw the conflicts and divisions as parts of power struggles. Voltaire was quite specific: the Christians have their origin in Jewish sectarianism and they thrive on doctrinal wars.

Voltaire, for all his fame as a proponent of tolerance, became a useful tool for intolerance against all religion, especially Christianity. His claims against Christianity, together with especially those of Rousseau, were those on which the attacks on the Catholic Church in France were based during the French Revolution. Though he was often correct in his assessment of the state of Christianity at the time, his hermeneutic was specifically twisted to show how tolerant of doctrine the Classical era had been and how intolerant Christianity had always been; his respect for historical truth was seriously compromised by this.

Of course this compromises his type of Caesarism - the enlightened totalitarian monarchy as legacy from the Modern side of Vico's thought. But it also severely compromises his own doctrine of enlightened tolerance by education and civilisation. His twisted hermeneutics produced seriously twisted doctrinal positions: the combination of 'scientism' and 'naturalism', as is clearly visible in the Dide-and-Booms book referred to above. I could have cited many present-day de-contextualised quotes from Voltaire going the same direction as Dide-and-Booms. But the book is significant for its pretence to responsible science as propaganda, and for its deep dialectic between freedom and natural law. This dialectic is clearly present in Voltaire. It is the consequence of the Modern ambiguity about 'natural law' on the one hand, and of the Cartesian-Lockean reduction of good science to the procedures of natural science.

What Voltaire did was to create tolerance by intolerantly undermining the 'infamous' using a dishonest hermeneutic bordering on fanaticism, and on the other to undermine the superstitions created by religion through en-lighten-ing the public. But again his approach to religion, the Bible and superstition was driven by his twisted interpretation theory. Not for one moment did he think of the explanations of Machiavelli and Hobbes, namely power-mongering.

REFERENCES

Dide, A., 1914, De Christelijke legend, Van Loo, Amsterdam. [ Links ]

Descartes, R., 1969, A discourse on method. Meditations on first philosophy. Principles of philosophy, Tr. By J. Veitch & A. O. Lindsay. Dent/ Dutton, London/ New York. [ Links ]

Dooyeweerd, H., 1963, Vernieuwing en bezinning; om het Reformatorisch grondmotief, Van de Brink, Zutphen. [ Links ]

Feyerabend, P.K., 1979, Against method. Outline of an anarchic theory of knowledge, Verso, London. [ Links ]

Haught, J.A., 1985, Positive atheism's big list of Voltaire quotations. http://www.Positivatheism.org/hist/quotes/voltaire. 5 pages. Consulted 10/12/12. [ Links ]

Herrick, J., 1985, Positive atheism's big list of Voltaire quotations. http://www.Positivatheism.org/hist/quotes/voltaire. 5 pages. Consulted 10/12/12. [ Links ]

Hocking, S., 2014, Les Hommes Sans Dieu: Atheism, Religion, and Politics during the French Revolution, Florida State University. Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations, the Graduate School. DigiNole Commons. Florida State Universityhttp://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8025&context=etd. [used 21-05-2015]. [ Links ]

Kant, I., 1975a, Idee zu einer allgemeine Geschichte in Weltbürgerliche Absicht, in Kant, I. Werke in zehn Bänden, hrsgg von Wilhelm Weischedel, WBG Darmstadt. pp. 33-50. (Translated into English: Kant, 1995. Idea for a universal history with political purpose. In: Political writings. Nisbet, H B (tr.). Reiss, H (ed.) Cambridge: UP. pp. 41-53. [ Links ])

Kant, I., 1975b, Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung? In Kant, I. Werke in zehn Bänden, hrsgg von Wilhelm Weischedel, WBG, Darmstadt. pp. 53-102. (Translated into English: Kant, 1995. An answer to the question: 'What is enlightenment'? In: Political writings. Nisbet, H B (tr.). Reiss, H (ed.) Cambridge: UP. pp. 54-60. [ Links ])

Kant, I., 1975c, Mutmasslicher Anfang der Menschengeschichte, in Kant, I., Werke in zehn Bänden, hrsgg von Wilhelm Weischedel, WBG, Darmstadt. pp. 33-50. ) Translated into English: Kant, 1995, Conjectures on the beginning of human history, in Political writings. Nisbet, H B (tr.). Reiss, H (ed.) Cambridge: UP. pp. 221-234. [ Links ])

Kant, I., 1975d, Zum ewigen Frieden, in Kant, I., Werke in zehn Bänden, hrsgg von Wilhelm Weischedel WBG, Darmstadt: WBG. pp. 33-50, pp.193 ff. [ Links ]

Locke, J., 1689, A letter on toleration, tr. by William Popple. http://www.constitution.org/jl/tolerati.htm. [used 21-05-2015. [ Links ]]

Machiavelli, N,. 1975, The discourses of Niccolo Machiavelli, Walker, L.J. (tr. & introd.), R & KP, London/Boston. [ Links ]

Mussolini, B., 1938, The doctrine of Fascism, Ardita, Rome. [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F., 1930, Also Sprach Zarathustra; ein Buch für alle und keinen, Kröner, Leipzig. [ Links ]

Rousseau, J-J., 1958, The social contract; the Discourses, Dent/Dutton, London/ New York. [ Links ]

Venter, J.J., 1992, 'Reason, Survival, Progress in Eighteenth Century Thought', Koers, 57: 189-214. [ Links ]

Venter, J.J., 1996, 'World-picture, individual, society', Neohelicon 23 (1):175-200. (Also in: Proceedings of the Bi-annual Congress of SASECS (Sept. 1993).Cape Town: UCT, 1994. [ Links ])

Venter, J.J.. 1999, 'Modernity': the historical ontology, Acta Academica, 31(2):18-46. [ Links ]

Venter, J.J., 2002, Of nature, culture and competition, Actas del VI Congreso Cultura Europea, Pamplona, 25 al 28 de octubre de 2000. Editas por Enrique Banusy BeatrizElio. Cizur Menor (Navarra), Thomson, Aranzadi, pp. 425-437. [ Links ]

Venter J.J. (Ponti), 2013a. 'Methodologies of targeting - Renaissance militarism attacking Christianity as weakness', Koers, 78(2), doi: 10.4102/koers.vt8i2.62.http://koersjournal.org.za/index.php/koers/articl/view/62 [ Links ]

Venter J.J. (Ponti), 2013b, 'Pragmatism attacking Christianity as weakness - methodologies of targeting', Koers 78(2), doi:10.4102/koers.v78i2.61 http://koersjournal.org.za/index.php/koers/article/view/61. [ Links ]

Vico, G., 1984. The New Science of Giambattista Vico, Unabridged translation of the third edition (1744) with the addition of 'Practice of the new science'. Cornell University Press, Ithaca/London. [ Links ]

Voltaire (F-M Arouet), 1765, Dictionnairephilosophique portatif, Nouvelle edition, Londres [Pdf: Google] [ Links ]

Voltaire, 1764, Liberty of the press, Tr by W Fleming (1901), http://classicliberal.tripod.com/voltaire/press.html. 2 pages. Consulted 05/23/12. [ Links ]

Voltaire. 1756, Poem on the Lisbon disaster. Or: An examination of that axiom: 'All is well', http://geophysics-old.tau.ac.il/personal/shmulik/LisbonEq-letters.htm. 3 pages. Consulted 09/25/12. Also Poème sur le desastre de Lisbon (1756). ATHENA, Pierre Perroud. http://athena.unige.ch/athena/voltaire/voltaire_desastre_lisbonne.html. Consulted 09/25/12 [ Links ]

Voltaire, 1763, On toleration, Tr. by J.M McCabe (1912). http://classicliberal.tripod.com/voltaire/toleration.html. 20 pages. Consulted 10/13/12. [ Links ]

Wiki, 2012a, Civil constitution of the clergy, 1790a. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civil_Constitution_of_the_Clergy. 1 page. [consulted 10/08/12]. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

J.J. (Ponti) Venter

Email: ponti.venter@nwu.ac.za

Dates:8 Dec 2015

1 Venter JJ (Ponti), 2013a. Methodologies of targeting - Renaissance militarism attacking Christianity as weakness.

Koers 78(2), doi: 10.4102/koers.vt8i2.62. http://koersjournal.org.za/index.php/koers/article/view/62 [There are no keywords in the articles themselves but the following terms may be helpful: Classicist, hermeneutic, heroic, exemplar, imperialist, Roman, competitiveness, balance of powers]

Venter JJ (Ponti), 2013b. Pragmatism attacking Christianity as weakness - methodologies of targeting. Koers 78(2), doi:10.4102/koers.v78i2.61 http://koersjournal.org.za/index.php/koers/article/view/61 [scientistic, method, polarize, Christianity, meekness, effective, solipsism]

2 Feyerabend's work, Against method (1979), is not some habracadabragoogeldygoo - it is formally structured in a logical way in paragraphs, chapters, arguing a point and thus contradicting in formal practice what he argues as doctrinal content.

3 Note: Voltaire is upset with this French writer, defending the infamous(religiously inspired) slaughter of St Bartholomew on the basis of a Classical example. The Ancient Greeks and Romans could never have been so barbarous. Voltaire probably did not read Machiavelli: the latter's Classicism was exactly a defence of Roman militarism and an attack on good Christian leaders for their meekness (cf. Venter, 2013c: 14ff.). Voltaire reduces all Ancient wars to but economic issues.