Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science

On-line version ISSN 2304-8263

Print version ISSN 0256-8861

SAJLIS vol.87 n.1 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7553/87-1-1988

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Provision and access to library support services for distance learners in Ladoke Akintola University, Nigeria

Musediq Tunji BashorunI; AbdulHakeem Olayemi RajiII; Omotayo Atoke AboderinIII; Yusuf Ayodeji AjaniIV; Esther Kehinde Idogun-OmogbaiV

ISenior Lecturer, Department of Library and Information Science, University of Ilorin, Nigeria. He is currently at Umaru Musa Yar'adua University, Katsina State, as a sabbatical Lecturer in the Department of Library and Information Science. bashorun.mt@unilorin.edu.ng ORCID: 0000-0002-5250-7239

IIPostgraduate student in the Department of Library and Information Science, University of Ilorin, Nigeria. bdulhakeemraji@outlook.com ORCID: 0000-0003-3878-8262

IIIPostgraduate student in the Department of Library and Information Science, University of Ilorin, Nigeria. tayorinde@yahoo.com ORCID: 0000-0003-4629-908X

IVPart-time lecturer in the Department of Library and Information Science, Al-Himan University, Ilorin, Nigeria. a.yusufayodeji@gmail.com ORCID: 0000-0002-2786-4461

VPostgraduate student in the Department of Library and Information Science, University of Ilorin, Nigeria. estnextlevel16@gmail.com ORCID: 0000-0002-8257-3835

ABSTRACT

This study examined the provision and access to library support services for distance learners (DLs) at Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH), Nigeria. A random sampling technique was used to select 341 DLs to whom to distribute a questionnaire; there was a response rate of 86.2%. Four research questions were answered by the study. The findings of the study revealed that most respondents agreed that the library offered DLs support services, but that they did not include document delivery, borrowing and internet services. The findings also revealed that just over half of the respondents considered the level of accessibility of library support services to be good. However, the study found that the level of satisfaction with library support services was low. Geographical isolation, poor internet connectivity, difficulty in borrowing from the library, among other factors, affected the use of library services. The study concluded that the LAUTECH library provided library services to DLs, but they were inadequate. Based on the findings, the study recommends that library management should facilitate the borrowing of books to DLs through reciprocal services with other libraries and embrace an empathetic marketing approach to reach DLs.

Keywords: Open education, library support programme, distance learner, university, LAUTECH, Nigeria

1 Introduction

Education plays a key role in the empowerment of citizens and the development of any nation. Tertiary institutions have the responsibility of providing quality education. They are institutions that provide post-secondary school education on a full-time, part-time and distance basis. Examples of tertiary institutions are universities, polytechnics, and colleges of education. A university can be described as an institution of higher learning providing facilities for teaching and research, and it is authorised to grant academic degrees (first degrees, master's degrees, and doctoral degrees). It is the pinnacle for the acquisition and advancement of knowledge. A university offers two main educational systems: conventional and open-distance education. The conventional system of education cannot accommodate all applicants because of the increasing number of individuals who want to improve their level of education. The rise in requests for higher education by learners of varying ages led to the introduction of distance education (Mayende & Obura 2013).

Distance learners (DLs) can be defined as students who receive formalised learning at a location outside the university campus (Adetimirin & Omogbhe 2011). Heaps (2009) opined that DLs are students who are separated by time or by distance from the institution in which they are enrolled for a course of study. Distance learning has various features that need special attention to achieve the primary goal of broad and accessible education to all. Akintayo and Bunza (2010) characterised DLs as adults with professional (job) or social (family) responsibilities. The researchers also classified DLs as having a limited formal education. Distance learning is now accessible in most countries in the world and many working adults choose distance learning to obtain qualifications and be certified in their chosen fields. The contending priorities of work duties, home responsibilities, and study commitments have constrained adults from fulfilling their desire for education that is flexible and accessible (Dzakiria et al. 2013). Therefore, the design of distance education aims to offer students maximum flexibility. It provides the learners freedom to choose the time, the place, and the pace of their study. Biao (2012) reported that national and international experience has shown that conventional education cannot meet the demands of the present-day socio-educational milieu, especially for developing countries like Nigeria, where this study is based. At present, the number of students admitted annually into conventional universities in Nigeria is low compared to the number of those who want a university education (Damilola 2013). This situation might be due to a lack of financial capacity and infrastructure at Nigerian universities which compelled an emergence of an open and distance learning (ODL) system. ODL is an innovative and cost-effective educational system to cater for the gap in educational provision.

As pointed out by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Culture Organisation (UNESCO 2002), the two main factors that have caused an increase in interest in distance learning are the growing need for continual skills development and retraining, and the technological advances that have made it possible to teach more subjects remotely. Transformation in global digitisation and the internet has propelled the concept of distance education in both developed and developing nations (Owusu-Ansah & Bubuama 2015). According to Maboe (2017), educational institutions have adopted the use of online technologies to enable teaching and learning and to augment interactivity between DLs, between DLs and lecturers, DLs and study material, and DLs and the institution. This assertion corroborated the findings of Karaduman and Mencet (2013) that the practices of distance learning are based on interactive information technologies that spread more widely than traditional modes of teaching.

The library is an essential support system that influences quality of education. It is the heart of any educational institution because it facilitates the acquisition of materials, research, and independent thinking, by providing resources to support teaching and learning activities. The library houses materials in both print and electronic formats for its users. An academic library, as a university-established library, must meet the information needs of all students and other stakeholders by providing library services equally (Association of College and Research Libraries [ACRL] 2008). The ACRL (2008) explained that every member of a faculty - student, administrator, non-teaching staff or the host community of an institution - is entitled to the library resources and services of that institution. This access includes direct communication with suitable library staff, irrespective of where members are enrolled, where they are located and their connection with the institution. Hence, academic libraries should meet the research and information needs of various categories of users, including the distance learners. DLs are expected to have the same opportunities as conventional students, including access to resources provided by libraries. According to Detar (2018), this means that service excellence in distance librarianship should include conducting outreach programmes for distance learners that parallel outreach programmes for on-campus learners.

Distance learning, as a substitute for on-campus learning, must guarantee the effective and appropriate provision of library support services for DLs (ACRL 2008). Library support services include facilitating access to library collections, instructional, and reference support, including information literacy training (Brooke 2011). Accessibility is the ability of DLs to attain or have access to the services provided for them by the academic library to support their scholarly work and research needs. Owusu-Ansah and Bubuama (2015) stated that DLs access library services and resources in different ways. The researchers noted that access can be direct and face-to-face; arbitrated by printed material, such as brochures and manuals; or mediated by technology using an array of media such as radio, telephone, and the internet. Successful direct access is distinguished by flexibility, availability, reliability, portability, efficiency, user friendliness, and convenience of service (Owusu-Ansah and Bubuama 2015). According to Molefi (2008), library support services for distance learning are carefully created and effectively used by an institution of higher learning to aid remote teaching and learning. Similarly, Owusu-Ansah and Bubuama (2015) regarded library support services as germane to helping DLs to overcome difficulties and challenges that affect the quality of their academic work. Chattopadhyay (2014) stressed that DL support services systems must be developed in a way that does not hamper the institutional needs and its ethics policy, for example being respectful to students, sending timely responses to them, and ensuring library services are accessible. Library support for off-campus programmes in Nigeria is becoming important, for the most part due to the development in distance education at academic institutions in the country.

Adoption of new technology by libraries has altered methods of service provision in recent times, enhancing the reach of libraries to DLs in increasingly varied ways (Casey 2009). Librarians should take into consideration the learning activities involved and the DLs before adopting electronic learning technologies. The central objectives for DL librarians should be to remove any obstacles in accessing services and resources, combined with enabling DLs to become independent and information literate learners (Jagger 2009, Cooke 2010). Students should have continuous access to resources that are suitable to support their learning. Academic libraries are responsible for the provision of equal information access to meet the information needs of all students. For the adequate and equal provision of library services to all stakeholders, Jagger (2009) reiterated that librarians should embrace technologies to facilitate and promote library service provision. Draper and Turnage (2011) stated that the creative use of technology is vital to the academic library's ability to assist DLs at their point of need.

Several studies (Adetimirin & Omogbhe 2011, Damilola 2013, Owusu-Ansah & Bubuama 2015) examined the provision of library support services to distant learners at various locations; however, based on our knowledge, none of these studies was carried out at Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH). Therefore, this study examined the provision of and access to library support services for DLs in LAUTECH, Ogbomoso, Nigeria. It is anticipated that the findings of this study will assist policy makers to formulate a policy that will improve library support services to DLs. The findings will also improve library practice by identifying gaps in support services that need attention in order to facilitate quality library services to distant learners in the twenty-first century.

2 Statement of the problem

Provision of and access to library support services for all users, especially DLs, cannot be overemphasised. The academic library, being the heart of the university system, provides support services for research, learning and teaching. The conventional system of education cannot accommodate all individuals because of the increasing number who want to improve their level of education. This increase in demand for higher education by learners of all ages brought distance education into the world (Mayende & Obura 2013). LAUTECH library provides library services to support teaching, learning and research activities for various categories of library users. However, it is not yet established whether these services adequately extend to meet the special needs of DLs. As supported by Damilola (2013), enough attention has not been given to the provision and access of library support services for DLs in Nigerian universities.

3 Objectives of the study

The main objective of the study was to examine the provision of and access to library support services for distant learners at LAUTECH. The specific objectives of the study were to:

• examine the library support services offered to DLs at LAUTECH;

• determine the level of accessibility of library support services by the DLs at LAUTECH;

• investigate the level of satisfaction of DLs with the existing library support services at LAUTECH; and

• identify the factors affecting the use of library support services by DLs at LAUTECH.

4 Literature review

Globalisation greatly impacts social, political and technological developments in the world, and it continues to facilitate change in these areas (Dursun, Oskayba & Gökmen 2013). These changes have a major impact on the needs of people, while affecting behaviour and the means of fulfilling those needs. They have opened our eyes to new approaches to understanding the education sector. Education is generally perceived as vital to social and economic development. African countries, however, face enormous obstacles in this regard. The rapidly rising demand for all levels and forms of education, as well as local and regional governments' inadequate capacity to grow the provision of education through traditional bricks-and-mortar institutions leaves ODL as a viable option to address growing demand for education (Igwe 2010).

Molefi (2008) noted that library support services in distance education are measures that are created to serve a particular purpose; to be used effectively by institutions of higher learning to support learning and teaching at a distance. Molefi (2008) regarded support services as important in aiding learners to overcome challenges that affect the quality of their scholarly work, giving them the assurance that they are not alone, but that the institution is invested in their progress. Owusu-Ansah and Bubuama (2015) observed student support as more overarching, involving the total environment in which learning occurs: the courses that offer the knowledge learning support; the DLs and the plans made for them; the learning and teaching process; and the evaluation of learning, programmes and institutions.

Byrne and Bates' (2009) findings supported the results in earlier research that reported that technological innovations would help librarians to offer DLs the same level of accessibility to services and resources as traditional on-campus students and would provide them with the knowledge to find the information they require. Anaraki and Babalhavaeji (2013) noted that the continuous growth of technologies has caused an increase in electronic information in libraries and on the internet; therefore, there is need for training on the best methods of accessing required information through information literacy training which empowers library users with the ability to identify an information need, to locate the needed information, and to evaluate and utilise the information effectively. Obasuyi and Usifoh (2013) noted that simple awareness of e-library resources was low, mostly due to inadequate computer and internet literacy skills. Similarly, research carried out in Uganda at the Mbarara University by Gakibayo, Ikoja-Odongo and Okello-Obura (2013) observed that the lack of computer skills and limited information literacy skills were the main challenges hampering students from utilising e-library resources, as DLs would need to do.

Studies conducted around the world relating to the provision of and access to library support services for DLs revealed several factors that deter DLs from fully utilising library support services. It is necessary to note that more challenges were reported in developing countries than developed nations. Maboe (2017) examined the usage of online interactive tools in an open distance learning context and revealed that DLs were technologically challenged, and that the institution did not provide them with the required support to acquire the skills needed to use services. Several studies (Mirza & Mahmood 2012, Kwafoa, Imoro & Afful-Arthur 2014) identified factors affecting the use of library support services by DLs as: geographical barriers; lack of awareness about library services and resources; budgetary and staffing limitations; technological barriers; poor information literacy; poor digital literacy skills; and interlibrary loan, document delivery, and acquisition and collection development problems. The geographical constraints for DLs is that they are located in different regions in the country that may be far from the physical institution. Cohen and Burkhardt (2010) stressed that budgetary and staffing constraints are common to all libraries and librarians, not just the ones who serve DLs. Libraries are constantly fighting stagnant or shrinking budgets. According to Owusu-Ansah and Bubuama (2015), the delivery of library material is often a complex issue. Furthermore, the lack of awareness of library resources and services is an obstacle to accessing library resources. As suggested by Brooke (2011) in relation to Sheffield Hallam University (SHU), the DLs at SHU had reasons for not using the library resources; among these being insufficient awareness of the services offered.

5 Methodology

Discussion of the methodology employed for data collection is discussed next, before study findings related to each specific objective are presented.

5.1 Research design

A descriptive survey research design was adopted for this study. Bechhofer and Paterson (2012) opined that research design varies depending on the place(s) where the research is conducted, the methods used to gather data and the analytic techniques applied.

5.2 Study population

According to Best and Kahn (2010), the population of a study is any group of individuals that has one or more features in common, which are of interest to the researcher. The total population for this study was the students enrolled in the DL programme during the 2017/2018 session at LAUTECH. As can be seen in Table 1, the population size was 2,326.

5.3 Sample size and sampling procedure

A sample is a subset of a population that is selected for analysis. Sampling is the process of selecting units, subsets or parts (for example, people, organisations) from a population of interest so that by studying the sample, the researcher may fairly generalise the results to the population from which they were chosen (Osuala 2001). The sample size of 341 was derived using the Raosoft software1. This study adopted the stratified random sampling technique to cater for each stratum of the population. The choice of stratified sampling technique was made because the population was composed of layers (strata) of discretely different levels of study of the DLs.

5.4 Research instrument

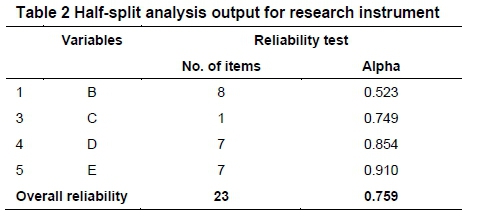

The questionnaire used as the data collection instrument was adapted from Buruga and Osamai (2019) and Owusu-Ansah and Bubuama (2015) and was entitled Distance Learning Library Support Services Questionnaire (DLLSSQ). The questionnaire was divided into five sections. Section A consisted of six items on demographic information (age, department, level of study, marital status, highest educational qualification, and the occupation of the DLs). Section B covered eight items on library support services available. Section C contained one item on the level of accessibility of library services offered. Section D covered seven items on the level of satisfaction by distance learning students. Lastly, Section E contained seven items on factors affecting the use of libraries by DLs.

5.5 Validity and reliability of the instrument

Validity is the extent to which an instrument measures what it is expected to measure. To ensure the face and content validity of the instrument used for the collection of data, the questionnaire was given to three experts in three departments (Library and Information Science; Test and Measurement; Statistics) to validate face and content validity. Their comments, observations and suggestions led to the adjustment of the items in the instrument so that it could be considered valid for use in this study. Reliability, as defined by Best and Kahn (2010), refers to the degree of consistency of a test or instrument to measure what it claims to measure. To ensure the reliability of the questionnaire used for data collection in this study, it was administered to twenty students in the DL programme at the University of Ibadan in Oyo State, Nigeria. The half-split reliability method was employed by dividing the responses into two equal halves using odd and even numbers of items in the questionnaire. Thereafter, the responses collected were subjected to Cronbach's alpha. The overall reliability coefficient of the twenty-three-item instrument was 0.759. This was high enough to confirm the instrument as adequate for this study. The reliability coefficients of each of the sub-scales are contained in Table 2, indicating the overall average reliability coefficient of the scales as 0.759.

5.6 Procedure for data collection

A total of 341 copies of the questionnaire were administered to the respondents in their respective study centres. To make the administration of the questionnaire easier and to ensure a high response rate, researchers distributed the questionnaires when the university was in session. Copies of the questionnaire were distributed, and responses were collected immediately after completion. Out of the total number administered, 294 copies of the questionnaire were properly filled out and returned. Descriptive statistics, such as frequency counts and percentages, were used to analyse the demographic data and to answer the research questions.

5.7 Response rate

The survey questionnaire received a response rate of 86.2%. Mugenda and Mugenda (2013) opined that a response rate of at least 50% is adequate for analysis of a survey, 60% is considered good while a 70% return rate is considered excellent. Therefore, the response rate of 86.2% for this study can be considered excellent. Figure 1 shows that thirty-two (10.9%) of the respondents were below the age of 25 years, fifty-eight (19.7%) were between 26-30 years, ninety-six (32.7%) were between 31-35 years, seventy-eight (26.5%) were between 36-40 years, twenty-four (8.2%) were between 41-45 years, and six (2.0%) were 46 years and above. The findings show that the majority of the respondents were between the ages of 31-35 years. Figure 2 shows the level of study of the respondents. Forty-three (14.6%) of the respondents were 100 level students (in their first year of study), thirty (10.2%) were 200 level students (second year of study), forty-three (14.6%) were in 300 level (third year), sixty-five (22.1%) were in 400 level (fourth year), and 113 (38.5%) were 500 level students. The findings indicated that the majority of the respondents were 500 level students, in other words, postgraduate students. Figure 3 shows that 192 (65.3%) of the respondents were government workers, seventy-six (25.9%) were employees of private organisations and twenty-six (8.8%) were self-employed. The findings of the study established that the majority of the respondents were government workers.

5.8 Library services offered to DLs by the library (Objective 1)

Table 3 shows that: 291 (99%) of the respondents agreed that the library offered library training (user education) for the DLs while three disagreed; 290 (98.6%) of the respondents agreed that the library provided web-based reference services for the DLs while four (1.4%) disagreed; 283 (96.3%) of the respondents agreed that the library offered an information guide to access library materials while eleven (3.7%) disagreed; 181 (61.6%) of the respondents agreed that the library offered electronic databases while 113 (38.4%) disagreed; 294 (100%) of the respondents disagreed that they were offered internet facilities; 294 (100%) disagreed that the library offers document delivery service; and 291 (99%) of the respondents disagreed that library offered them access to library books while three agreed. The findings of the study show that DLs were offered access to certain library services, however, they were not offered access to internet facilities, document delivery services or delivery of physical books.

5.9 Levels of accessibility of library support services for DLs (Objective 2)

Table 4 showed that 148 (50.3%) of the respondents agreed that library services were easily accessible. However, 101 (34.4%) of the respondents indicated that library services were not easily accessible. Also, forty-five (15.3%) of the respondents agreed that they never accessed library services provided by the LAUTECH library. The findings of the study indicated that library support services are easily accessible by the majority, but they also imply that accessibility to library support services needs to be improved.

5.10 Levels of satisfaction of DLs with existing library support (Objective 3)

Table 5 shows that DLs' satisfaction with the provision of current awareness services provided through email and telephone scored the highest percentage with 263 (89.5%) agreeing they were satisfied while thirty-one (10.5%) saying they were not satisfied with this service. The findings of the study also showed that 215 (73.1%) of the respondents agreed that they were satisfied with online user education services provided by the library while seventy-nine (26.9%) were not satisfied. In addition, 143 (48.6%) of the respondents agreed that they were satisfied with the library's virtual reference service while 151 (51.4%) were not satisfied. The findings showed that 121 (41.2%) of the respondents were satisfied with the provision of social media services while 173 (58.8%) were not satisfied. Additionally, 294 (100%) of the respondents were not satisfied with the provision of access to interlibrary loan services. In the overall assessment, 202 (68.7%) of the respondents were not satisfied with the library services provided by LAUTECH to DLs. The findings show that the level of satisfaction of library support services by DLs is low.

5.11 Factors affecting the use of library support services by DLs (Objective 4)

Table 6 shows that the majority (289; 98.3%) of the respondents agreed that difficulty in borrowing library books affected their use of libraries. This frequency is followed by 270 (91.8%) indicating poor internet connectivity as a factor affecting their use of libraries. In addition, 264 (89.8%) showed that they faced difficulty in obtaining study materials from the library. The other factors affecting use of the library were rated in the following sequence: geographical isolation (251; 85.4%), inability to interact with library staff (154; 52.4%), lack of library and computer training (ninety-eight; 33.3%) and lack of IT tools (computers, telephones) (sixty-nine; 23.5%). The findings show that there are numerous factors that affect the use of library support services provided by the LAUTECH library to DLs.

6 Discussion

The findings of the study revealed that LAUTECH library offered DLs several services, such as web-based reference and referral services, telephone-based services, information guides to access materials, web-based library training, and access to electronic databases. However, DLs were not offered an internet facility, documentary delivery service, or circulation service. The findings agree with the results of earlier studies (Kramer 2010, Parsons 2010, Brooke 2011, Ahenkorah-Marfo & Nikoi 2019) that reported that services that are provided to DLs are web-based reference and referral services, information guides to access materials, telephone-based services and others. This study's findings revealed that the majority of the library services were accessible to DLs, except for the borrowing of the library's physical resources. The findings contradicted the research of Mayende and Obura (2013) that library services are not accessible to most ODLs based far from the institution. In addition, the findings revealed that the level of satisfaction of library services rendered to DLs by the library is poor.

This study also revealed the factors that affected the DLs use of the library support services. They were: difficulty in borrowing library books, poor internet connectivity, difficulty in obtaining study materials, and geographical isolation. Moreover, the findings revealed that lack of library and computer training, inability to interact with library staff, and lack of IT tools (computers, smartphones) were considered minor factors that affected the learners' use of the library support services. These findings were corroborated by the results of the studies of Mirza & Mahmood (2012), Kwafoa et al. (2014) and Buruga and Osamai (2019) that showed poor internet connectivity as a major factor that affected the use of the library support services. Similarly, the findings supported the result of Adetimirin and Omogbhe (2011), that the inability to borrow books from the library is one of the major constraints for DLs.

7 Recommendations and conclusion

This study was undertaken to examine the provision and access to library support services for DLs at LAUTECH in Ogbomoso. The study concluded that the LAUTECH library provided several support services required by DLs that were similar to those provided by other academic libraries. However, DLs were not provided with internet access or document and circulation services. Despite the provision of a variety of initiatives by LAUTECH to support library services, the level of satisfaction of DLs is low. Therefore, there is a need to suggest means of improving library support services to satisfy DLs at LAUTECH.

Based on the findings of this study and the conclusions drawn, the recommendation was made for the library to provide borrower privileges at other libraries (reciprocal services) to DLs, like those given to conventional students at their institutional library. As stressed by Girton (2018), using empathetic marketing to reach distance-learning students demonstrates to them that library staff know about their needs and can help meet them. This service would encourage the DLs to use the resources and services of partner or sister libraries closer to them to satisfy their information needs. Effective document delivery services should also be provided to make it possible to deliver materials remotely to DLs to overcome geographical barriers, thus assisting to curb the effects of geographical isolation and encourage the learners to utilise library services more often. Furthermore, through personal commitment, DLs should provide internet access for themselves by subscribing to a reliable network provider using their smartphones. University management should upgrade institutional internet connectivity to improve online library support services, such as online library orientation, online information guides and online tutorials for better student performance.

References

Adetimirin, A. and Omogbhe, G. 2011. Library habits of distance learning students of the University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). [Online]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/527 (26 June 2020)

Ahenkorah-Marfo, M. and Nikoi, S. K. 2019. Change for a better paradigm: assessing the library services for distance learners in an African institution. Journal of Library and Information Services in Distance Learning, 13(3): 307-318. [ Links ]

Akintayo, M. O. and Bunza, M. M. 2010. Perspectives in distance education. Bauchi, Nigeria: Ramadan Publishers. [ Links ]

Alfrih, F. M., Hepworth, M. and Goulding, A. 2011. The role of academic libraries in supporting distance learning programmes in Saudi Arabia: why and how? Journal of Library and Information Services in Distance Learning, 5(3): 82-91. [ Links ]

Anaraki, L. N. and Babalhavaeji, F. 2013. Investigating the awareness and ability of medical students in using electronic resources of the integrated digital library portal of Iran: a comparative study. The Electronic Library, 31 (1): 70-83. DOI:10.1108/02640471311299146. [ Links ]

Association of College and Research Libraries. 2008. Standards for distance learning library services. Chicago: ACRL. [Online]. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/guidelinesdistancelearning (25 August 2020) [ Links ]

Bechhofer, F. and Paterson, L. 2012. Principles of research design in the social sciences. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Best, J. W. and Kahn, J. V. 2010. Research in education. 10th ed. New Delhi: PHI Learning. [ Links ]

Biao, I. 2012. Open and distance learning: achievements and challenges in a developing sub-educational sector in Africa. In Distance Education. P.B. Muyinda, Ed. London: IntechOpen. 27-62. [ Links ]

Brooke, C. 2011. An investigation into the provision of library support services for distance learners at UK universities: analysing current practice to inform future best practice at Sheffield Hallam University. Master's thesis. University of Sheffield Hallam. [ Links ]

Buruga, B. A. and Osamai, M. O. 2019. Operational challenges of providing library services to distance education learners in a higher education system in Uganda. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). [Online]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5831 (25 August 2020)

Byrne, S. and Bates, J. 2009. Use of the university library, e-library, VLE, and other information sources by distance learning students in University College Dublin: implications for academic librarianship. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 15(1):120-141. [ Links ]

Casey, A. M. 2009. Distance learning librarians: their shared vision. Journal of Library and Information Services in Distance Learning, 3(1): 3-22. [ Links ]

Chattopadhyay, S. 2014. Learner support services in open distance learning system: case study on IGNOU. Distance Learning and Reciprocal Library Services: Is Public Library Network the better option. [Seminar]. 6-7 June 2014.

Cohen, S. and Burkhardt, A. 2010. Even an ocean away: developing Skype-based reference for students studying abroad. Reference Services Review, 38(2): 264-273. [ Links ]

Cooke, N. 2010. Becoming an androgogical librarian: using library instruction as a tool to combat library anxiety & empower adult learners. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 16(2): 208-227. [ Links ]

Damilola, O. A. 2013. Use of electronic resources by distance students in Nigeria: the case of the National Open University, Lagos and Ibadan Study Centers. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). [Online]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/915/ (23August 2020)

Detar, M.D. 2018. Mind the gap! Making the leap to reach distance students through on-campus event. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 12(3-4): 189-197. DOI: 10.1080/1533290X.2018.1498632 [ Links ]

Draper, L. and Turnage, M. 2011. Utilizing technology. In Going the distance: library instruction for remote learners. S. Clayton, Ed. London: Facet. 83-92 [ Links ]

Dursun, T., Oskayba, K. and Gökmen, C. 2013. The quality of service of the distance education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 103: 1133-1151. [ Links ]

Dzakiria, H., Kasim, A., Mohamed, A. H., and Christopher, A. A. 2013. Effective learning interactivity as a prerequisite to successful open distance learning (ODL): a case study of students in the northern state of Kedar and Perlis, Malaysia. The Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 14(1): 111-125. [ Links ]

Gakibayo, A., Ikoja-Odongo, J. and Okello-Obura, C. 2013. Electronic information resources utilization by students in Mbarara University Library. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). [Online]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/869/ (23 September 2020).

Girton, C. 2018. Showing students we care: using empathetic marketing to ease library anxiety and reach distance students. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning. DOI:10.1080/1533290X.2018.1498634.

Heaps, E. 2009. SCONUL Task Force on Access for DL - Distance learners: information resource issues for policymakers. London: SCONUL [ Links ]

Igwe, O. U. 2010. Libraries without walls and open and distance learning in Africa: the Nigerian experience. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). [Online]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/4301/ (23 September 2020).

Jagger, K. 2009. Learning and mastering the tools of the trade. In Going the distance: library instruction for remote learners. S. Clayton, Ed. London: Facet. 19-26. [ Links ]

Karaduman, M. and Mencet, M. S. 2013. Attitude and approaches of faculty members regarding formal education and distance learning programs. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 106: 523-532. DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.059. [ Links ]

Kramer, S. 2010. Virtual libraries in online learning. In Handbook of online learning. K. Rudestam and J. Schoenholtz- Read. Eds. London: Sage. 445-465. [ Links ]

Kwafoa, P.N.Y., Imoro, O. and Afful-Arthur, P. 2014. Assessment of the use of electronic resources among administrators and faculty in University of Cape Coast. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). [Online]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1094/.

Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH). 2018. LAUTECH open and distance learning center. [Online]. http://lodlc.lautech.edu.ng/odl (24 September 2020)

Maboe, K. A. 2017. Use of online interactive tools in an open distance learning context: Health studies students' perspective. Health SA Gesondheid, 22: 221 -227. [ Links ]

Mayende, J. E. K. and Obura, C. O. 2013. Distance learning library services in Ugandan universities. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 7(4): 372-383. [ Links ]

Mirza, M. S. and Mahmood, K. 2012. Electronic resources and services in Pakistani university libraries: a survey of users' satisfaction. The International Information & Library Review, 44(3): 123-131. [ Links ]

Molefi, F. 2008. Context. Paper presented at the Distance Education Workshop for Setswana Part-Time Writers, DNFE. (Unpublished).

Mugenda, A. G. and Mugenda, O. M. 2013. Research methods: quantitative and qualitative approaches. Nairobi: ACTS Press. [ Links ]

Obasuyi, L. and Usifoh, S.F. 2013. Factors influencing electronic information sources utilised by pharmacy lecturers in universities in South-South, Nigeria. African Journal of Library, Archives and Information Science, 23(1): 45-57. [ Links ]

Osuala, E. C. 2001. Introduction to research methodology. 3rd ed. Onitsha: Africana-First Publishers Limited. [ Links ]

Owusu-Ansah, S. and Bubuama, C. K. 2015. Accessing academic library services by distance learners. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). [Online]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1347/ (25 August 2020)

Parsons, G. 2010. Information provision for HE distance learners using mobile devices. The Electronic Library, 28(2): 231 -244. [ Links ]

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation. 2002. Open and distance learning trends, policy and strategy considerations. Paris: UNESCO Division of Higher Education. [Online]. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000128463 (24 August 2020). [ Links ]

Yen, H. L. 2009. The role and integration of digital libraries in e-learning. In Handbook of research on digital libraries: design, development and impact. Y. L. Theng, Ed. London: Info Science Reference. 476-481. [ Links ]

Received: 3 November 2020

Accepted: 18 June 2021