Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science

On-line version ISSN 2304-8263

Print version ISSN 0256-8861

SAJLIS vol.86 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.7553/86-1-1814

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Relational-based resilience of a public university: a case study on losing a library by Mzuzu University in Malawi

MacDonald KanyangaleI; Eugenio NjolomaII

ISenior Lecturer in Management at the Graduate School of Business and Leadership, University of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. kanyangalem@ukzn.ac.za ORCID: 0000-0003-2259-1449

IILecturer in the Department of Governance, Peace and Security Studies, Mzuzu University, Malawi. njoloma.e@mzuni.ac.mw ORCID: 0000-0002-2241-5835

ABSTRACT

Following the destruction of the university library by fire in 2015, this retrospective study explores the nature of the capabilities of organisational resilience exhibited by Mzuzu University (Mzuni) as perceived by Heads of Departments (HoDs) in the university. Limited research has focused on what resilient university libraries do and how organisational resilience is achieved in practice. Eight HoDs, selected using stratified random sampling, were interviewed and data analysed using content analysis. Results reveal that the nature of organisational resilience exhibited by Mzuni lacked a proactive approach. Predominantly, Mzuni relied on unexpected, external and relational-based capabilities to improvise library services. An interplay of various organisational, individual and relational capabilities was central to the improvisation of library services. However, ambidextrous structure, culture and leadership, and the pursuit of systemic resilience are fundamental if Mzuni is to be truly resilient. The integrative framework of proactive organisational resilience proposed in this study can be used by librarians, leaders of public universities and human resources practitioners to build the composite capability of organisational resilience for the university library before adversity occurs.

Keywords: Resilient library, organisational resilience, framework of proactive organisational resilience, relational-based resilience

1 Introduction

Resilience is a strategic asset for a university library as disruption is prevalent in the contemporary university. Bodenheimer (2018: 365) is disenchanted that to "learn about resilience and how to cultivate resilience in libraries, one must read in th e psychology and management literature to extrapolate what might be useful". The ability of the university librarian to embed into the day-to-day library services practices that enhance resilience is critical for a university library for it to bounce back or bounce forward when faced with high impact and low probability disruptions.

Mzuzu University (Mzuni) in Malawi lost its university library due to electric fire in the early hours of 18 December 2015 (Chavula 2015: 1). In the words of Hayes (2016: 1), "[the library] building and all of its books - around 45,000 volumes -were consumed, along with the equipment and furniture". As a central service, the library at Mzuni could no longer serve 4,000 undergraduate students, 187 postgraduate students, and academics from four diverse faculties namely Environmental Sciences, Tourism and Hospitality Management, Information Science and Communications, and Health Sciences. Additionally, the library was not available for use by four centres: the Centre for Open and Distance Learning, the Centre for Water and Sanitation, the Centre for Security Studies, and the Testing and Training Centre for Renewable Energy and Technologies (Mzuzu University 2015: 7). Re-building and re-stocking a university library is not an easy or quick fix.

In Malawi, the loss of a public university library due to fire is not common. The type of disruptions or challenges which are common to the majority of university leaders emanate from student and academic protests, pressure to produce more with few resources, and the demand to improve the quality of education but also deal with the effects of massifying university education (Chawinga and Zozie 2016: 2). University leaders in Malawi grapple with the challenges of running chronically under-funded and over-enrolled public universities (Chawinga and Zozie 2016: 2). Mushemeza (2016: 236) emphatically points out that "government investment in several African public universities is dwindling against the pressure to improve [both access and] quality". McManus et al. (2007: 1) are mindful that many organisations that have faced similar catastrophes never reopen; others evolve so radically that they are hard to recognise from their pre-crisis form. These issues raise questions of how Mzuni responded to the loss of the university library.

2 Research problem

Since 2015, when fire destroyed the library at Mzuni, no known study has explored the micro-level interactions and processes to reveal the nature of capabilities or lack thereof displayed by the university or the library in the endeavour to bounce back or bounce forward from the disaster. Extant literature on organisational resilience and university libraries reveals three startling gaps in research.

First, what resilient organisations do and how organisational resilience is achieved in practice is still unclear (Giustiniano et al. 2018: 3). Few studies have investigated resilience capabilities in an organisation (Duchek 2019: 1). Second, the growing body of research on what generally makes a university resilient has not specifically focused on the context of the library (Bodenheimer 2018, Canney 2012). This gap is interesting, as the context in which organisational resilience is enacted alters not just its development but also its realisation. The adversity at Mzuni provides a critical case to explore the nature of micro-level processes and capabilities, which constitute organisational resilience. It must be acknowledged that most organisational researchers of resilience have focused on high-risk organisations such as firefighting services, hospitals, police and the military (Giustiniano et al. 2018: 3). Other researchers such as Borekci, Rofcanin and Gürbüz (2015) investigated the influence of relational dynamics on organisational resilience in the private sector. Reinmoeller and Baardwijk (2005) revealed that the most resilient organisations in the business sector orchestrate a continuous balance of four innovative strategies: exploration, knowledge management, entrepreneurship and cooperation.

Third, there are few insights into the inner workings of organisational resilience (Giustiniano et al. 2018). Few researchers have tried to describe the resilience process in detail. According to Duchek (2019: 5), "we do not really know if resilience is the result of designed processes or perhaps the outcome of improvisation and luck". To summarise, the lack of focus on the context of libraries as well as the blend of specific capabilities that underlie organisational resilience for a public university library reflect key research gaps of interest in this study. Aptly, Coutu (2002: 46) says, "resilience is one of the great puzzles of human nature and how it works in a university, particularly for libraries, is also a bit of a puzzle".

3 Research objective

The objective of this phenomenological study was to investigate the nature of capabilities of organisational resilience exhibited by Mzuni following the loss of the university library, as perceived by academics who were Heads of Departments (HoDs) when the incident occurred. The key research question dwelled on the nature of the capabilities reflecting organisational resilience which were displayed by Mzuni following the loss of the university library. This qualitative study is valuable as it brings to the fore the micro-level interactions and processes within and between internal and external resources to reveal how relational-based capabilities are predominant in the resilience of a library in a public university. Consequently, a framework of organisational resilience that is integrative and insightful for strategic leaders, librarians and human resources practitioners is proposed, illustrating the necessity for proactive, composite and systemic resilience for the university library as and when adversity occurs. The article starts by focusing on the overview and fundamental aspects of organisational resilience. This is followed by a discussion of the ontology of organisational resilience adopted in this study. Subsequently, it presents the research methodology, findings, and discussion. A framework of proactive organisational resilience for a library in a public university is proposed before the conclusion.

4 Overview of organisational resilience

The concept of resilience is increasingly becoming popular across disciplines such as health, medicine, information management, disaster management and economics (Tierney & Bruneau 2007: 14). However, the complex phenomenon of organisational resilience is still in its infancy and thus nebulous, not only in the discipline of Library and Information Sciences, but also in management. The root of organisational resilience is traceable to the Latin word resiliere - "the material characteristic of bouncing back after a setback" (Giustiniano et al. 2018: 3). The three main p erspectives of organisational resilience evident in literature hinge on impact resistance and recovery, adaptation, and anticipation (Connelly et al. 2017, Lengnick-Hall, Beck and Lengnick-Hall 2011, Van der Merwe, Biggs and Preiser 2018).

First, impact resistance and recovery emphasise a rebound or defensive orientation of resilience, pronounced coping strategies, an ability to resume expected performance levels within a short period after the adversity, and learning to bounce back (Van der Merwe, Biggs and Preiser 2018). Thus, resilience is an "organisation's ability to resist adverse situations and/or the ability to recover after disturbance and return to a normal state" (Duchek 2019: 3). Second, adaptation-oriented perspectives maintain that organisational resilience responds to unexpected events by making changes and emerging from the crisis stronger than before. Learning, growth and transformation are the key expectations (Lucy and Shepherd 2018). For instance, Lengnick-Hall, Beck and Lengnick-Hall (2011: 244) define organisational resilience as "a firm's ability to effectively absorb, develop situation-specific responses to, and ultimately engage in transformative activities to capitalise on disruptive surprises that potentially threaten organisational survival". Third, the proactive approach to organisational resilience incorporates the aspect of anticipation: predicting and preventing potential danger before damage is done. The National Academy of Sciences acknowledges preparatory capabilities by asserting that resilience is "the intrinsic ability of a system to prepare and plan for, absorb, recover from, and more successfully adapt to adverse events" (Connelly et al. 2017: 48). It is one thing to recognise, after the fact, how resilient an organisation is, while it is quite another to understand prospectively what the resilience requires.

5 Four fundamental aspects of organisational resilience

As alluded to earlier, literature on organisational resilience is generally fragmented and dispersed over diverse disciplines (Burnard and Bhamra, 2011: 5583). In this vein, it is scholarly prudent to outline a handful of fundamental issues to understand the conceptual commonalities and complexity of the elusive concept of organisational resilience. One of the fundamental aspects of organisational resilience relates to whether resilience is an outcome or a process. Outcome-focused views of organisational resilience emphasise factors that have had positive or negative impacts on an organisation's performance during adversity to distinguish resilient organisations from those less so (Purvis et al. 2016). Alternatively, organisational resilience as a dynamic and on-going developmental process does not have an end point. Duchek (2019) asserts that there are three stages in the process of organisational resilience, namely anticipation (which requires proactive action), coping (which requires concurrent actions to develop and implement solutions) and adaptation (which requires reactive action of reflection and learning to create change). In a different vein, detection and activation, resilient response, and organisational learning are three-process stages proposed by Burnard and Bhamra (2011). It is prudent to question why the process of organisational resilience is portrayed not only in orderly, progressive stages but also in non-progressive, iterative stages. This dichotomy of outcome or process is simplistic as it is possible to understand organisational resilience in terms of both process and outcome.

The second fundamental aspect of organisational resilience distinguishes general from specified resilience. Specified resilience entails the decomposition of the system and its environment to determine what internal parts should be resilient and for which external aspects of the environment this resilience is specifically required (Van der Merwe, Biggs and Preiser 2018). Conversely, general resilience refers to the capacity of a system to withstand all hazards including novel and unforeseen ones while continuing to provide critical functions (Van der Merwe, Biggs and Preiser 2018). Balancing specified and general resilience is necessary as effort channelled into developing only one kind of resilience may reduce the other kind in an organisation as a system (Van der Merwe, Biggs and Preiser 2018).

The multi-level nature of organisational resilience is a third fundamental aspect of organisational resilience. For example, psychological resilience explores "positive adaptability in anticipation of (or in response to) shocks" not only at the level of an individual but also a team or a community (Manfield 2016: 35). Teams have the capacity for positive adaptation through collective interactions rather than as isolated individuals. Research is lacking on the effect of organisational-level inputs on team resilience. This gap raises questions of how resilience at one level (such as strategic or operational) interacts with another to manifest resilience as an outcome or to facilitate the process of being a resilient library.

Lastly, the notion that organisational resilience is multidimensional is fundamental to understand its conceptual complexity (Giustiniano et al. 2018). From a systems viewpoint, Tierney and Bruneau (2007) identified four dimensions (4R framework) to evaluate system performance: robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness and rapidity. Lengnick-Hall, Beck and Lengnick-Hall (2011) draw from human resources to identify three dimensions of organisational resilience: cognitive resilience (mindfulness, sense-making and critical reflection), behaviour resilience (improvisation, experimentation, learning more about the situation, and abilities to collaborate), and contextual resilience (settings to integrate cognitive and behaviour resilience). This study adopts a multi-dimensional view of the resilience management process which hinges on the building of situational awareness, managing key vulnerabilities, and increasing adaptive capacity as suitable to explore what happens before, during and after adversity. The next section seeks to delve into the ontology of organisational resilience used in this study.

6 Ontology of organisational resilience

Organisational resilience may be understood as a process involving different types of interrelated tasks or capabilities before and after a disruptive event in an organisation (Giustiniano et al. 2018: 3). McManus et al. (2007:1) surmise that:

resilience is a function of an organisation's situation awareness, management of keystone vulnerabilities and adaptive capacity in a complex, dynamic and interconnected environment.

From the above definition, three tasks of organisational resilience, discussed below, are identifiable for further conceptual clarity:

6.1 Task of building situational awareness

First, situation awareness arises from the organisation's understanding of its entire operating environment (McManus et al. 2007: 1). For instance, anticipatory capability is key to identifying crises, trigger factors and consequences in the current and expected future of a university. An increased awareness of resources at the disposal of the organisation, both internally and externally, is also part of building situational awareness (McManus et al. 2007: 1). Awareness of the expectations of stakeholders, limitations, obligations and the minimum operating requirements are not only vital in shaping a clear and coherent response but also in delineating recovery priorities in various types of crises. McManus et al. (2007: 1) advise that there are five indicators to assess situational awareness. These are: clarity of roles and responsibilities (role definitions, expectations, knowledge, scope); degree of understanding hazards, potential consequences and impact; awareness of how to manage hazards; knowledge of insurance and other available support mechanisms; and connectivity awareness.

6.2 Task of managing keystone vulnerabilities

Second, the task of managing keystone vulnerabilities is about identifying, prioritising and targeting "components of an organisational system which have the potential to cause the greatest negative impact either catastrophically or insidiously" (McManus et al. 2007: 24). Reducing exposure to risk, enhancing capacity to respond, but also being prepared to reduce consequences of failure, are ways of managing keystone vulnerabilities (McManus et al. 2007: 20). Indicators of managing keystone vulnerabilities include planning strategies (on-going risk identification and emergency and recovery planning) and employee participation in emergency exercises. Other indicators such as capability and capacity of internal resources (physical components, human resources, process resources) as well as external resources (expected availability of external assistance, services, supply network) are critical in the way keystone vulnerabilities are managed in order to unlock the resilience potential of an organisation (McManus et al. 2007: 20). Lastly, an understanding of the links between components and the keystone vulnerabilities that may arise from these as interconnected parts of a system and not in isolation is a key indicator of organisational connectivity.

6.3 Task of increasing adaptive capacity

Lastly, organisational resilience involves adaptive capacity or having "elements that make up the culture of an organisation, which allow it to make decisions in both a timely and appropriate manner in a crisis and also identify and maximise opportunities" (McManus et al. 2007: 2). Achieving resilience depends on adaptation, which includes learning, and organisational change or positive adjustment. Dalzell and McManus (2004 cited in Bhamra, Dani & Burnard 2011) are explicit that

adaptive capacity reflects the ability of the system to respond to changes in its external environment and to recover from damage to internal structures within the system that affect the ability to achieve its purpose.

There are five indicators of adaptive capacity (McManus et al. 2011). The first indicator is the extent to which an organisation experiences the negative effects of a silo mentality and the occurrence of related mitigation strategies. The second indicator is the effectiveness of communication pathways and relationships with stakeholders in day-to-day situations and crises (McManus et al. 2007: 2). The third indicator relates to vision and outcome expectancy. Vision is useful as a critical crisis response tool to provide a framework for identifying and directing adaptive activities of an organisation during a crisis. The fourth indicator focuses on the degree of information and knowledge acquired, retained and transferred within the organisation and between linked organisations. Lastly, leadership visibility, availability and transparency in decision-making is key to achieving change to resources, activities and actors (McManus et al. 2007: 2). Figure 1 depicts the three interrelated tasks and their indicators, which may occur concurrently or iteratively in shaping a 'situated response to and recovery' from a crisis. Having explored the concept of organisational resilience used in this study, it is timely now to turn to research methodology.

7 Research methodology

This section describes how participants in the critical case of Mzuni were selected, and how data was collected and analysed.

7.1 Paradigm

Phenomenology is the study of experience from a first-person point of view or the understanding of social and psychological phenomenon from the perspective of people involved (Schwandt 2015). Phenomenology is suitable for this study because it upholds that the source of all meaning and value is the lived experience of human beings. This phenomenological study adopted a social constructivist paradigm to delve into the lived experiences of HoDs regarding the nature of organisational resilience displayed by Mzuni to restore its library services.

7.2 Sampling

Stratified, purposive sampling was used to select eight HoDs at Mzuni. Selection of participants was based on three criteria: experience of the loss of the library in 2015; evidence of teaching at Mzuni from a year before and three years after the loss of the library so as to reflect and elaborate on the unfolding of different events and activities taking place until the date of the interview; and being in the position of HoD from 2014-2018. Participants reflected on changes and patterns of microlevel interactions, processes and outcomes, which unfolded over four years as Mzuni tried to recover from the loss of the library. While HoDs are leaders at the coalface of teaching and learning within a university, they are also close to students and support staff. This location makes them well suited to elaborate on what happened at Mzuni which depicted the nature of organisational resilience found in the library and the university. Participants were aged 35 to 50 years and had an average of ten years of work experience with Mzuni.

7.3 Data collection

Eight in-depth, face-to-face, semi-structured interviews were audio-recorded with HoDs. The interview guide was drawn from the notion of organisational resilience involving three tasks: building situation awareness, managing key vulnerabilities, and adaptive capacity. To reflect on situational awareness, participants focused on roles and responsibilities during the period of response, recovery, and adaptation following the fire; awareness of the range of hazard types and their consequences (positive or negative) within the library and university; and awareness of network inter-dependencies within the university and its community of internal and external stakeholders. Additionally, minimum operating requirements, expectations of stakeholders, response and recovery priorities, and awareness of obligations and limitations in relation to disruptions that the university may have, as well as any government aid were considered. To elaborate on aspects of managing keystone vulnerabilities, participants reflected on the extent of risk and emergency planning; employee and stakeholder participation in exercises for emergency management and recovery; and capability and capacity of internal resources. The interview guide additionally helped participants reflect on expectations of the organisation for the availability and effectiveness of external resources to assist in a crisis, as well as the university's connection to other organisations to ensure the availability of expertise and resources in the event of a crisis. To uncover aspects of adaptive capacity, participants discussed the extent of silo mentality; the effectiveness of communication pathways; and the effectiveness of internal and external relationships. The guide also helped participants to reflect on how vision was a critical crisis response tool; the extent of acquiring, retaining and transferring knowledge and information throughout the organisation; and the extent to which leadership and management encouraged flexibility and creativity as other parts of adaptive capacity.

7.4 Data analysis

Interview data was transcribed and member checked before analysis. Open coding and constant comparison were used as part of content analysis to deduce key categories and group them into dominant themes reflecting on how Mzuni responded to and recovered from the loss of the library. The details of the research process and direct quotes from participants in this study are given to provide an audit trail and to enhance dependability and credibility.

8 Results

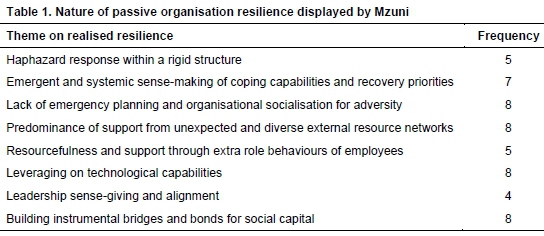

Overall, results reveal that the resilience - quick restoration of library services with little disturbance to the academic calendar - exhibited by Mzuni lacked a proactive approach in the anticipation stage of organisational resilience. Generally, Mzuni's response was haphazard within a rigid structure, lacked emergency planning and organisational socialisation for adversity, and relied on emergent sense-making of coping and recovery priorities. There was a predominance of support from unexpected and diverse external resource networks. Resourcefulness was demonstrated and there was support from employees who took on extra roles and leveraged technological capabilities. Key aspects of resilience shown at Mzuni include leadership sense-giving and alignment, building of instrumental bridges to external help, and bonds for internal social capital within the university. Frequency of responses on key themes are shown in Table 1, followed by details of each finding to depict the nature of organisation resilience at Mzuni.

8.1 Haphazard response within a rigid structure

Five of the HoDs concurred that the response was haphazard, typified by a lack of anticipation capabilities to recognise the range of potential risks and impacts of current and emerging hazards and to address them proactively. Role ambiguity, lack of clear emergency planning, and lack of nimble decision-making processes in a non-routine situation compelled organisational members (staff, frontline employees) to stick closely to the rules as reported below.

Students who noticed a small fire in the library at 2 or 3 am reported at the potter's lodge. I got an SMS...then pictures through WhatsApp of the burning library. Some students and staff tried to get the keys but were told by security that...you will not get the keys to go in until the registrar comes... The city assembly fighters came, but late. They were unable to put out the fire. (HoD6)

To illustrate the haphazard and uncoordinated nature of the response of the university, one of the interviewees focused on the looting of property.

My office was adjacent to the library before moving to the new offices. People had to break doors to rescue their properties. People looted some of the good office computers..projectors. Some of our friends lost money.. laptops and degree certificates. I no longer leave things in the office, no matter what. (HoD3)

8.2 Lack of emergency planning and organisational socialisation for adversity

All eight HoDs lamented that Mzuni lacked emergency planning and emergency exercises as part of a proactive approach to prepare for adversity and socialise employees and students to it. One of the interviewees elaborated on this point as follows.

As HOD, I do not hear of any emergency plans or planning on what to do when fire occurs ...in the library or anywhere on campus. If you now take a student to a library and ask how he or she can sound a fire alarm. the student will not tell you. Although we have more fire extinguishers now on campus, we still have never had mock fire drills (HoD1).

The culture of not tracking and addressing risks, not engaging in scenario thinking, and the lack of adequate insurance was evident at the library and university levels as follows.

I was a student here. The problem of poor electrical wiring in the library has been there for long. The registrar's office ignores reports on risks; waits until something happens to finally react. Having scenario ABCD...is not our culture here. I even doubt if we had a sensible insurance cover for the library (HoD6).

8.3 Emergent and systemic sense-making of coping capabilities and recovery priorities

Seven HoDs agreed that Mzuni manifested a quick grasp of the variety of emerging fears, dilemmas and limitations of both internal and external stakeholders. One of the interviewees sensed the inadequacy of coping capabilities of academics that would help them to sustain their teaching and assessment techniques and would allay their fears of reputational damage.

We were afraid of starting a semester with course outlines whose prescribed books we did not have. The question was, where are we going to get books? The assignment I am giving, where are my students likely to get the resources? I remember somebody asked me, how can a university run without having the library? (HoD4)

A variety of concerns from external stakeholders (for example, parents and employers of students, with the national government as a key external stakeholder) were central to emergent and holistic sense-making at Mzuni.

We had pressure.employers were concerned that their staff who are students may not finish in time. Parents were also fearful that we might not open..delay or compromise the academic calendar. Government wanted us to re-open as soon as we could. (HoD7)

As a result of quick, collective and interactive sense-making by leaders, Mzuni diagnosed three recovery priorities: quick improvisation on the part of the library, re-stocking of the library, and providing access to e-resources to staff and students, as reported below.

[As a university] we agreed to convert the assembly hall into a small library. This meant relocating the kitchen out of campus and no venue for big classes to write examinations. This forced us to expedite the completion of the auditorium. Tracking books on loan to return to the library and re-stocking the library was another priority. How would students access journals without computers? So that was another priority. (HoD5)

8.4 Predominance of support from unexpected and diverse external resource networks

All the HoDs concurred that Mzuni restored its library services (such as, furniture, books, technical advice, media coverage) predominantly based on support from unexpected external and diverse sources. The diversity of external sources (which were local as well as international and included publishers and the media) and the simultaneous focus on immediate and long-term needs is illuminated in the following comment.

The librarian of Malawi College of Medicine came to give us a talk on how we can access electronic books and electronic information resources... Chancellor College.... Seventh Day Adventist University gave us books. Anglia, the publishers, the University of Strathclyde in Scotland gave us books, tables, and library shelves from their small library. Another university gave us technical advice. The University of Virginia Tech in America is drawing the designs for our future library. Presentations of donations were open to media and leaders of students. Lecturers made announcement of new books while the librarian used notice boards to tell everyone about new books. (HoD3)

Interestingly, the only expected support was from government, but this support proved to be inadequate to restore library services in the absence of other assistance.

Government promised some millions of kwacha for the recovery but only released less than promised. It was not enough to do anything tangible. If we had depended on that alone, I do not think things will have progressed and re-opened with a temporary library. (HoD1)

8.5 Resourcefulness and support through extra role behaviours of employees

Five of the HoDs reported that resourcefulness and academics assuming extra roles were strategic in supporting students and the university to cope with the adversity. Voluntarily, to support their students, some academics downloaded, printed, and copied whatever reading materials were key, thereby reflecting both resourcefulness and the ability to improvise.

If I knew that the material is important for students to perform in a particular course or assignment, I would simply download it, print it, and share with students. Let us say I have a very important book, which my students can also benefit from. I would run copies that I shared with students, and then put some on short loan. I could not do otherwise until when we had key and latest books. (HoD8)

Notably, some academics donated personal books to the library, while others took up voluntary roles to champion fundraising, such as this HoD who organised a dinner:

My family and I gave the university books, which were relevant and could be used in basic sciences, education, and medical courses. In addition, I chaired the Mzuzu University Library fundraising dinner. Most employees expected government to give us money. This is why there was little support for the dinner from Mzuni members. (HoD2)

8.6 Leveraging on technological capabilities

All eight HoDs concurred that the library leveraged technology by using the proficiency of staff in information and communications technologies to ensure continued access to e-resources for academics, though not students, in the absence of library services, as reflected below.

These days librarianship is going digital. We subscribed to some good online databases such as Sage, Emerald and more. Lecturers were able to access e-resources using computers and internet connectivity in their offices. However, this was not the case for students. (HoD6)

Digital skills acquired by academics and students, coupled with the active provision of e-resources and services by the periodical section of the library, revealed some of the ways that Mzuni bounced forward from the adversity.

When students returned in March, dedicated library staff gave them sessions on how to get e-resources. Students and academics got digital skills to search and get latest e-resources. We never had periodical section that was very serious as it is today. Our periodical section is reliable on e-resources and recent journals. (HoD8)

8.7 Leadership sense-giving and alignment

Four HoDs agreed that a series of internal brainstorming meetings that had been held were fruitful as a mechanism for university leaders to embrace diverse views, make sense of the shared urgency, and give direction to restore library services amid a variety of uncertainties.

The team of the Vice Chancellor ...Deputy Vice Chancellor, University librarian. Most Deans...the President and secretary of Student Union were all on campus even on 25 December, examining different scenarios. Already Mzuni had a deficit.. the new dilemma was that the temporary library was not budgeted for. The second semester was not far. (HoD3)

Furthermore, organisational members learnt to live with discomfort, which reflected a collective mindfulness necessary for the improvised library to operate despite its shortfalls.

In the old library, you had space to put your bags. There is no such space in the makeshift library with only 250 seats for over 1,000 students. Bags are kept outside. If it is raining, we have to rush and get our bags. In the corridors, we encouraged each other. (HoD1)

8.8 Building instrumental bridges and bonds for social capital

All eight HoDs were cognisant of the politics of sense-giving embedded in visits by political leaders, which created bridges for international donors to support Mzuni, as demonstrated below.

The State President came to see and assess the burnt library. The president was concerned... assured us of support from government. And also asked donors to help. Through the visits of political leaders, individuals pledged.. .different organisations such as UNESCO started to donate books. I also remember that we had a visit by the Minister of Education. (HoD6)

Cross-functional committees created a bond between diverse employees (those with different functions, specialisations and positions within the hierarchy) around specific priorities, unlocking collective creativity and a commitment to pursue both immediate and long-term needs. The following is what one of the interviewees had to say:

The library committee decided that people in the acquisitions lead efforts of liaising with departments to identify the priority books to buy as soon as possible. We got together as one and had all the key books required before re-opening for second semester... Members of the construction committee ensured our temporary library was ready. Last month some members were in the USA to follow-up the design of our future library. (HoD4)

9 Discussion

Organisational resilience of a public university can be inhibited by structural rigidity, which undermines employee empowerment, flexibility and creativity to respond to adversity. To avoid haphazard response to adversity, a proactive approach to organisational resilience is fundamental in a university library as it allows people to prepare and practice emergency responses. This approach shapes the outcomes of organisational resilience. However, Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003: 108) warn that "good outcomes are not enough to define resilience...". Although the outcome of a quick restoration of library services with little disturbance to the academic calendar indicates resilience by Mzuni, there are critical and underlying issues which show the existence of a structural and cultural approach to resilience which is not able to support the foundations of a resilient university and its library. Resilience as a composite capability emerges from an interplay of individual, organisational and relational capabilities which are key, not only to anticipate and cope with adversity, but also adapt from it.

Firstly, the structure at Mzuni (for example, role ambiguity and rigidity) inhibited members of the organisation from escaping their day-to-day reality in order to be flexible, decisive and creative in exploiting resources for a coherent emergency response. The metaphor often used to describe the structure in public universities is that it is 'mechanistic' due to its exceptional inflexibility. However, recent studies show that organisations that do not focus on just exploitation or just exploration, but rather pursue them concurrently, can perform better in terms of survival in adversity and, therefore, achieve better long-term success (Giustiniano et al. 2018: 3). Leja and Nagucka (2013: 161) advise that "the university authorities [as ambidextrous leaders] are expected to play the role of an orchestra conductor", needing to embrace and reconcile paradoxical thinking if they are to create resilience for the university library. Empowered, cross-functional committees with diverse members from across the university were useful in the relentless but appropriate pursuit of short-term as well as long-term demands (Denyer 2017). This point illustrates how structure and interdependencies need to facilitate quick and systemic support for the resilience of the library within the university. Vârheim (2016) is clear that culture is another contextual factor critical in shaping resilient-oriented values and behaviours of organisational members. Lucy and Shepherd (2018) concur that resilience emerges from an organisation's culture and learning. New objects on the Mzuni campus, such as fire extinguishers and sprinklers, are critical, and reflect awareness on the part of the organisation of fire risk and organisational learning. However, this change in awareness is insufficient to create a culture of resilience. Organisational socialisation of students and staff needs to focus on underlying assumptions if resilience-enhancing values and behaviours are to be embedded in organisational members (Schein 2010: 29).

Secondly, Mzuni lacked a proactive approach to organisational resilience that could have embedded emergency planning, key to avoiding a haphazard response, to allow people to practice emergency responses on a regular basis before the fire at Mzuni. Thinking about resilience when there is no current catastrophe is a hallmark of a resilient university and its library (Economist Intelligence Unit 2015: 1). Anticipation capabilities, as part of the first stage of organisational resilience, are about "observing internal and external developments to identify and track critical developments and potential threats and - as far as possible - to prepare by taking actions in the present that promote desirable outcomes and circumvent disruptions in the future" (Duchek 2019:3). The anticipation stage is vital to support the coping and adaptation stages of organisation resilience (Lucy and Shepherd 2018). While anticipation capabilities cannot accurately foresee a 'black swan' event, the emphasis is on preparation and readiness whenever it occurs. Taleb (2007) asserts that a black swan event deviates beyond what is normally expected of a situation, characterised by low probability based on past knowledge. Although the probability of a black swan event is low, when it happens it has a massive impact (Taleb 2007). In pursuing a proactive approach to organisational resilience, it is key to bear in mind that black swan events are prospectively unpredictable, but retrospectively predictable.

Thirdly, the resilience of Mzuni - to improvise library services quickly with minimal disturbance to the academic calendar - is also questionable as it was based predominantly on unexpected and external relational-based capabilities. McManus et al. (2011) are explicit that it is the "guaranteed" expectation upheld by an organisation - that effective external resources will be available to assist in a crisis - that characterises a resilient organisation. Unfortunately, the only expected support for Mzuni was financial (from the government), which was inadequate for the restoration of library services. This gap underscores the need to develop and implement deliberate and externally focused relational strategies. These are strategies for cooperative networks or bridging social capital which can access diverse, guaranteed resources realisable as and when adversity occurs.

Furthermore, this study has found that organisational resilience for a university library is a composite capability, which emerges from an interplay of individual, organisational and relational capabilities in anticipating, coping with, and adapting to adversity. Four organisational-level capabilities of resilience that contributed to the passive resilience of Mzuni can be inferred. First, strategic leaders of Mzuni had to set strategic direction amidst uncertainty, urgency and a lack of internal resources. Second, implementation of strategic improvisations (such as the modification of the assembly hall to an interim library and the relocation of the kitchen) was key. Organisations that survive adversity regard improvisation as a core capability. Urgency and bricolage ('making do') are the two main drivers of improvisation. A culture that promotes urgency and experimentation, but also tolerates mistakes arising from novel ideas (not flawed execution), provides a suitable context to nurture improvisation. Training on improvisation is key to enhance resilience. Third, the leveraging of technology for digital library and communication (via, for example, WhatsApp) was also valuable in sharing timely emergency information and ensuring that academics and students had access to a variety of online resources during the coping stage of the adversity. Interestingly, the digital skills acquired by library staff were critical in two ways: library staff used their digital skills to support faculty members to pursue research and these skills were helpful to academics and students in accessing online materials for education.

Lastly, interpersonal communication was also key to promoting organisation-wide communication through various means (committees, media, notices, in-class announcements). Informal communication was important for self-organisation as stakeholders came together voluntarily to help Mzuni to cope with adversity (the fundraising committee is one example).

This study shows that relational and organisational capabilities also interacted with three individual-level capabilities exhibited by organisational members of Mzuni. Thus, engagement in sense-making as an individual (but also as a member of a committee or in corridor conversations) was essential to realising pragmatic resilience through improvisation. The development of digital skills, thus creating resilient human capital, enabled academics, students and library staff to access resources from the virtual world. The cognitive and behavioural aspects evident in these findings resonate with Lengnick-Hall, Beck and Lengnick-Hall (2011) who argued that cognitive and behavioural dimensions of members of the organisation are key in organisational resilience. The capability of resourcefulness was critical in adversity as academics, operating as individuals as well as in groups (for example, the fundraising committee), exploited resources to address immediate challenges through discretionary behaviours not recognised by the reward system. Borekci, Rofcanin and Gürbüz (2015: 6841) concur that "resilience is socially enabled and developed via the interactions and relations between system members; each party to this system is expected to contribute to, and enhance the survival of, the overall system". In this respect, future research needs to include views of students, ordinary lecturers and non-academic staff who are also part of the library and university systems.

10 Proposed framework for proactive organisational resilience of a library in a public university

Drawing from the above, it is posited that anticipatory activities and behaviours that are largely proactive and occur independently of adverse events are the essence of proactive organisational resilience. A proactive approach to resilience requires ambidextrous leadership as a bedrock for emergent and holistic sense-making as well as sense-giving in a supportive context replete with uncertainty (Probst, Raisch and Tushman 2011). Resilient-building leadership integrates organisational, individual and relational-based capabilities in a simultaneous pursuit of immediate and long-term issues in adversity (Teixeira and Werther 2013: 338). Figure 2 presents a proposed integrative framework of proactive organisational resilience for a library in a public university like Mzuni.

11 Implications

Three specific implications of the findings of this study are discussed.

11.1 Ambidextrous structure and culture

Structure and culture that impede the four facets of urgency, psychological and managerial empowerment of organisational members, quick decision-making processes, and execution at the coalface are not appropriate to cultivate organisational resilience for the university library. Public universities need to create an ambidextrous organisational structure and culture to balance at least four aspects. These are: freedom and control of frontline employees; dual capabilities of exploitation of current conditions in order to bounce back in adversity and exploration of resources for bouncing forward; strategic agility in bureaucratic practices; and problem-driven innovation for immediate and opportunity-driven solutions . Implementing an ambidextrous structure is necessary, though not easy, for leaders in public universities which are often characterised as not ready for change. A culture of blindness to risk is not a foundation for proactive organisational resilience. Rather, it calls for change which embeds underlying assumptions that reinforce anticipation capabilities, an ethos of risk management and an organisation-wide commitment to cultivate resilient students, academics and library services. It is the university and its library that must socialise its organisational members to be resilient, to "get ahead of change to survive and thrive" (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2015:2).

11.2 Digital skills for digital library

The digital skills of library staff, academics and students play an important part in the resilience of the university library. University librarians and human resources practitioners are encouraged to identify and address gaps in the digital skills of staff within the library so that they can work effectively in the digital world and support students (who are predominantly digital natives) and academics (some of whom are digital immigrants). Digital proficiency among library staff is core to improving digital fluency at the university which will enhance student resilience and research (Raju, Schoombee and Raju 2013). A clear digital strategy for the resilience of the library and its users is necessary in a virtual world of ubiquitous access to digital content. This type of strategy should also ensure access to affordable, high-speed internet connectivity and include solutions to the frequent experience of electricity outage which affects most university libraries in Africa.

11.3 Building systemic resilience as a set of developable capabilities

Technical capabilities within the library system are fundamental but, on their own, they are inadequate to shape resilience for the library located in a broader university system. This insufficiency calls for building a proactive and systemic approach across multiple levels in the university and for the library regularly to ensure situational awareness. The role of the university librarian needs to evolve to embrace the challenge of being a relationship builder. The university librarian needs to champion the integration of a set of individual, organisational and relational-oriented capabilities in order to balance effectively resilience specific to the library with that which is generally necessary for the library. Building systemic resilience proactively also entails developing effective resilience capabilities across library functions and the three stages of the process of organisational resilience before adversity arises. Without a systemic alignment which integrates capabilities of resilience i n the public university with those specific to the library, a resilient library is an illusion.

Although the etic viewpoint of organisational resilience for the library upheld by HoDs (who are predominantly library users) is valuable, it remains one-sided. Future research needs a more emic view of diverse library practitioners from public universities to refine, validate, and enhance the explanatory power of the proposed framework of proactive organisational resilience for the university library. Where possible, the use of documents (such as minutes of meetings) to complement interview data may also be fruitful. The findings are from a particular context, hence not generalisable to all public university libraries. However, they are transferable to many similar contexts.

12 Conclusion

The nature of Mzuni's resilience - quick restoration of library services with little disturbance to the academic calendar - is a misleading outcome which hides many critical and underlying issues. The approach to organisational resilience was not proactive. It also ignored the anticipation stage and its capabilities. Anticipation capabilities and good preparation before adversity occurs are hallmarks of resilience for the university library regardless of the type or magnitude of the adversity. Public universities purposely need to develop and prioritise relational-based capabilities and digital strategy as the bedrock on which to build resilience to avoid reliance on external resources. Simultaneous development and integration of a variety of organisational, individual and relational capabilities is fundamental, not simply because organisational resilience is a composite capability, but to embrace the spectrum of stages in the process of organisational resilience. Ambidextrous structure, culture and leadership form the underlying backdrop for a university library to be resilient. This study is a key scholarly step towards clarifying and integrating organisational, individual and relational capabilities necessary to build the composite capability of organisational resilience for a university library before adversity strikes.

References

Bhamra, R., Dani, S. and Burnard, K. 2011. Resilience: the concept, a literature review and future directions. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18): 5375-5393. DOI:10.1080/00207543.2011.563826. [ Links ]

Bodenheimer, L. 2018. Leadership reflection: resiliency in library. Journal of Library Administration, 58(4): 364-374. DOI:10.1080/01930826.2018.1448651. [ Links ]

Borekci, D.Y., Rofcanin, Y. and Gürbüz, H. 2015. Organizational resilience and relational dynamics in triadic networks: a multiple case analysis. International Journal of Production Research, 53(22): 6839-6867. DOI:10.1080/00207543.2014.903346. [ Links ]

Burnard, K. and Bhamra, R. 2011. Organizational resilience: development of a conceptual framework for organizational responses. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18): 5581-5599. DOI:10.1080/00207543.2011.563827. [ Links ]

Canney, J.W. 2012. What makes a higher education institution resilient: an interpretive case study. PhD Thesis. University of St. Thomas. [Online]. http://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_orgdev_docdiss/15 (19 November 2017). [ Links ]

Chavula, J. 2015. Fire guts Mzuni library. The Nation. 19 December. [Online]. https://mwnation.com/fire-guts-mzuni-library/ (19 December 2015).

Chawinga, W.D. and Zozie, P.A. 2016. Increasing access to higher education through open and distance learning: empirical findings from Mzuzu University, Malawi. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(4): 1-20. DOI:10.19173/irrodl.v17i4.2409. [ Links ]

Connelly, E.B., Allen, C.R., Hatfield, K., Palma-Oliveira, J.M. Woods, D.D. and Linkov, I. 2017. Features of resilience. Environment Systems and Decisions, 37(1): 46-50. DOI:10.1007/s10669-017-9634-9. [ Links ]

Coutu, D.L. 2002. How resilience works. Harvard Business Review, 80 (5): 46-56. [Online]. https://hbr.org/2002/05/how-resilience-works. [ Links ]

Denyer, D. 2017. Organisational resilience: A summary of academic evidence, business insights and new thinking by BSI and Cranfield School of Management. Cranfield : BSI and Cranfield University. [ Links ]

Duchek, S. 2019. Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Business Research, 1 -32. [Online]. DOI:10.1007/s40685-019-0085-7.

Economist Intelligence Unit. 2015. Organisational resilience: building an enduring enterprise. London: British Standards Institute. [Online]. https://www.bsigroup.com/LocalFiles/en-US/Organisational-Resilience/Org-res-EIU-report.pdf (31 March 2019).

Giustiniano, L., Clegg, S.R., Cunha, M.P. and Rego, A. 2018. Elgar introduction to theories of organisational resilience. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [ Links ]

Hayes, J. 2016. Rebuilding a Malawian library after disaster. Library Connect. 10 June. [Online]. https://libraryconnect.elsevier.com/articles/rebuilding-malawian-library-after-disaster (25 February 2019).

Leja, K. and Nagucka, E. 2013. Creative destruction of the university. GUT FME Working Paper Series A, No. 14/2013(14). Gdansk: Gdansk University of Technology, Faculty of Management and Economics. [Online]. https://depot.ceon.pl/bitstream/handle/123456789/14389/WP_GUTFME_A_14.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [ Links ]

Lengnick-Hall, C.A., Beck, T.A. and Lengnick-Hall, M.L. 2011. Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 21: 243-255. DOI:10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.07.001. [ Links ]

Lucy, D. and Shepherd, C. 2018. Organisational resilience: developing change-readiness. Horsham: Roffey Park Institute. [Online]. https://www.roffeypark.com/wp-content/uploads2/Organisational-Resilience-Developing-Change-Readiness-Reduced-Size.pdf (11 December 2018). [ Links ]

Manfield, R.C. 2016. Organizational resilience: a dynamic capabilities approach. PhD thesis. University of Queensland Business School. DOI:10.14264/uql.2016.203. [ Links ]

McManus, S., Seville, E., Brunsdon, D. and Vargo, J. 2007. Resilient management: a framework for assessing and improving the resilience of organizations. Canterbury: University of Canterbury. http://hdl.handle.net/10092/2810. [ Links ]

Mushemeza, E.D. 2016. Opportunities and challenges of academic staff in higher education in Africa. International Journal of Higher Education, 5(3): 236-246. DOI:10.5430/ijhe.v5n3p236. [ Links ]

Mzuzu University. 2015. Annual report 2013/2014. Mzuzu: Mzuzu University. [ Links ]

Probst, G., Raisch, S. and Tushman, L.M. 2011. Ambidextrous leadership: emerging challenges for business and HR leaders. Organizational Dynamics, 40: 326-334. [Online]. https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:48300. [ Links ]

Purvis, L., Spall, S., Naim, M. and Spiegler, V. 2016. Developing a resilient supply chain strategy during 'boom' and 'bust.' Production Planning & Control, 27:7/8, 579-590. DOI:10.1080/09537287.2016.1165306. [ Links ]

Raju, R., Schoombee, L. and Raju, R. 2013. Research support through the lens of transformation in academic libraries with reference to the case of Stellenbosch University Libraries. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 79(2): 27-38. DOI:10.7553/79-2-155. [ Links ]

Reinmoeller, P. and Baardwijk, C. 2005. The link between diversity and resilience. MIT Sloan Management Review, 26(4): 61-65. [Online]. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/files/1999/11/e1f321a3bb.pdf. [ Links ]

Schein, E.H. 2010. Organization culture and leadership: A dynamic view. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Schwandt, T. A. 2015. The Sage dictionary of qualitative inquiry. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication. [ Links ]

Sutcliffe, M. and Vogus, T.J. 2003. Organizing for resilience. In Positive organizational scholarship: foundations of a new discipline. K.S. Cameron, J.E. Dutton and R.E. Quinn, Eds. San Francisco: Berrett-Kehler. [ Links ]

Taleb, N.S. 2007. The Black Swan: the impact of the highly improbable. 2nd ed. New York: Random House. [ Links ]

Teixeira, E.O. and Werther, W. Jr. 2013. Resilience: continuous renewal of competitive advantages. Business Horizons, 56(3): 333-342. DOI:10.1016/j.bushor.2013.01.009. [ Links ]

Tierney, K. and Bruneau, M. 2007. Conceptualizing and measuring resilience: a key to disaster loss reduction. TR News, 250: 14-17. [Online]. https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/trnews/trnews250_p14-17.pdf. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, S.E., Biggs, R. and Preiser, R. 2018. A framework for conceptualizing and assessing the resilience of essential services produced by socio-technical systems. Ecology and Society, 23(2):12. DOI:10.5751/ES-09623-230212. [ Links ]

Vârheim, A. 2016. A note on resilience perspectives in public library research: paths towards research agendas. Proceedings from the Document Academy, 3(2): article 12. [Online]. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/docam/vol3/iss2/12 (12 January 2019). [ Links ]

Received: 7 May 2019

Accepted: 18 May 2020