Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science

On-line version ISSN 2304-8263

Print version ISSN 0256-8861

SAJLIS vol.85 n.1 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.7553/85-1-1820

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Leadership roles within the ranks in Nigerian academic libraries

Ngozi Odili

Librarian II in the Library Department, Baze University, Abuja, ngoziodili@gmail.com ORCID: 0000-0002-1432-4765

ABSTRACT

The study investigated leadership roles in academic libraries with the purpose of discovering librarians' perceptions of leadership as well as finding evidence of leading from within the ranks and not necessarily from a managerial or supervisory position. The reason for this investigation was to identify whether library staff, regardless of their position within the organisation, are free to demonstrate their leadership potential by creating change or motivating other colleagues to work towards a shared vision. The research methodology applied was the quantitative method. Using the case study of two mid-northern Nigerian universities, findings show that, although librarians in non-supervisory roles demonstrate leadership attributes that help improve services delivered to users in their libraries, supervisory staff are more likely to suggest new ideas than non-supervisory staff. Therefore, there is a need for the academic library to refocus its leadership structure and be willing to acknowledge other leadership styles, especially ones that will encourage librarians of all ranks to showcase their talents and creative abilities, particularly in areas or services where their interests lie, in order to promote library innovation and drive service development.

Keywords: Nigerian academic libraries, leadership, academic libraries, library cadres, leadership within the ranks, non-managerial leadership

1 Introduction

Studies reveal that there are various leadership styles and that the definition of leadership continues to evolve (Janes 2014, Mosley 2014). In defining leadership, one needs first to highlight the distinction between 'managers' and 'leaders'. Contrary to popular assumption, 'leadership' is not 'management': while leadership involves creativity, innovation, imagination, motivation, trust and assisting the development of others, management has to do with problem-solving, planning, budget planning, staffing and controlling (Hernon 2007, Allner 2008). Townley (2009) explained the managerial position as having an administrative authority which can be transferred or assigned, whereas leadership is reciprocatory and voluntary, with the leader choosing to lead and the followers agreeing to follow. A modern-day definition describes leadership as "a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal" (Northouse 2013: 4). The contemporary approach claims leadership has three basic components: influence, followership and goals (Hernon 2007, Mosley 2014, Deakin University 2018).

In addition to leadership being a function of process, the literature also reveals that for libraries to continue to survive, leadership must be visible in all positions. According to Dewey (1998: 93), it is important for twenty-first century librarians on every rung of the organisational ladder to demonstrate leadership skills - "not just as managers of people but of programs, services and activities" - otherwise libraries will not be able to compete with modern technology-driven information outlets. In other words, for an organisation to thrive, the adopted leadership styles are critical in achieving sustainable, innovative growth. This study aimed to examine the extent to which academic librarians of different ranks understand leadership outside the context of management; and whether librarians, regardless of their rank and whether supervisory or not, can demonstrate leadership attributes required to achieve organisational goals and proffer innovative solutions that can advance library services and their parent institutions.

The research was conducted within the context of two Nigerian universities: Baze University, a privately-owned university situated in Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria, and the Federal University of Technology Minna, (FUTMINNA), a government-owned university in the Niger State of Nigeria. The libraries of both universities are staffed by librarians from different ranks with titles ranging from Library Assistant, Assistant Librarian, Librarian I, Librarian II and Senior Librarian, to Principal Librarian. All are led by a top management position, the University Librarian. In both universities, the criteria required for librarians to advance through the ranks are based on academic qualifications and scholarly publications. The office of the University Librarian is equivalent to a professorial position. A common occurrence, mostly in public universities and to a lesser extent in private institutions of higher education, is that senior librarians are seen heading a department that consists of a team of librarians of lower ranks. Also mostly in public universities, the office of the University Librarian, unlike the other cadres, is often offered to an individual nominated and appointed by the university body.

To achieve the aims of this study, the following objectives were formulated: identify the extent to which librarians, regardless of rank, are permitted to introduce and lead new initiatives in their libraries; investigate and identify how the initiatives led by non-supervisory library staff have improved and advanced library services to the benefit of users; and investigate the types of leadership roles in Baze University and FUTMINNA libraries. The study also aimed to answer the following questions:

• Do libraries recognise and acknowledge that leadership can exist within the various ranks in the academic library?

• To what extent are innovative librarians at all levels of the library involved in engendering changes that are advancing the library services offered to users?

2 Literature review

The section starts by examining the prevalent leadership structure in Nigerian academic libraries. Also discussed is the need to accommodate leadership within the library ranks, particularly less hierarchical leadership styles that have the potential to drive a sustainable library innovative process. The review concludes by examining the issues that need to be considered while adopting this approach.

2.1 Leadership in academic libraries

The leadership structure common in libraries is a managerial top-down, hierarchical system. It consists of an executive director or a university librarian who supervises a management team of principal and senior librarians who, in turn, manage department heads and other personnel (Townley 2003, Bartlett 2014, Janes 2014, Harris-Keith 2016). As described in previous works of literature (Aiyebelehin 2012, Jerome 2018, Ugwu & Okore 2019), the leadership structure in Nigeria's university-based academic libraries is mostly restricted to a highly transactional succession of managerial leaders. This succession rarely accommodates the context of leadership style that encourages employees' creativity in the workplace. Consequently, the services and operations of most academic libraries in Nigeria still rely mainly on traditional library systems which were not designed to accommodate the changes introduced by the information age.

According to Mosley (2014: 2), managerial leadership plays an important role in establishing an "organisation's strategic priority and culture" and, although the top-down model may be the most commonly adopted, it is suggested that the top-down method is not necessarily the best approach in all situations. There are other leadership approaches that are more effective in helping to harness employees' skills and talents, promote the delivery of quality services, provide customer satisfaction and achieve other general objectives of an organisation (Stephens & Russell 2004, Goulding & Walton 2014). Despite the advantages of having a titled leader directing the organisation, both Topping (2002) and Mosley (2014) propose another leadership approach: leading from all sides. The proposal for leadership at all levels as a strategy to accomplish organisational objectives is a contrarian view to normal library practice (Lubans 2010). However, according to Baker (1993, cited in Stephens & Russell 2004: 240) "anyone who wants to have a better idea of what is happening and what is about to happen needs to read widely in a number of sources one normally might consider exotic or tangential". Just as innovations and techniques used in advancing today's modern libraries originated in other fields outside of librarianship and information sciences, leadership styles and organisation development models were originally invented in business or management fields before they were adopted by other organisations (Stephens & Russell 2004).

2.2 Leadership from all levels

Leading from a managerial position is far from the only place a person can lead (Hernon 2007, Cawthorne 2010, Iannuzi 2014). A famous quote from Henry Ford (founder of Ford Motors) states that "you don't have to hold a position in order to be a leader" (Anderson 2013). However, inspiring a vision and bringing it to reality without holding formal managerial office can be difficult as it can arouse suspicion of plans to usurp current management (Janes 2014). Nonetheless, leading without an office or title is gaining recognition and increasingly being studied to inspire librarians and staff at all levels in the organisation to approach work proactively (Bartlett 2014). Different terminology used in the literature to describe leadership from all levels includes, among others, 'leadership from all sides'; 'leadership from within'; 'grassroots leadership'; 'personal leadership'; 'distributed leadership'; and 'transformational leadership'.

Janes (2014) gave descriptions of what it means to lead at all levels where professionalism, confidence, knowledge, ideas, vision and contributions can reverberate across the organisation thanks to an employee's personal attributes, such as communication and interpersonal skills, instead of office or rank. Also, Bartlett (2014) described those leading from all sides as "the people that others approach for help with problems, who thoughtfully contribute ideas and comments at staff meetings, who make decisions in their areas of professionalism with confidence, and who stay informed of developments in the larger organisation. In short, they influence others...". According to lannuzi (2014), these are also people who distinguish themselves through volunteering to accept responsibilities without needing to be compelled to do so. John C. Maxwell, a successful author and speaker on leadership, explained that influence can manifest itself anywhere and with anyone, regardless of the humbleness of a job title (Maxwell 2005). The overall success and progress of libraries may be critically dependent on the ''commitment, engagement, and culture'' present in levels outside of authoritative or managerial roles (Mosley 2014: 2). Such influences garnered from anywhere within the organisation despite rank or title might just be what is most needed to move libraries forward in Nigeria.

2.3 Leadership, not management: matching the employees' skills-set

Although it has been argued that the demonstration of leadership attributes within all the ranks of the organisation can encourage creativity and drive sustainable innovation in the organisation, it is important to note that the ability of an employee to demonstrate innovative leadership skills at a lower or middle level does not necessarily mean such staff will be able to function effectively as an administrative or managerial leader (Mosley 2014). Usually leading from within the ranks occurs where personnel are strongly motivated by passion and with a strong desire for getting things done (Janes 2014). According to Mosley (2014: 4), "different leadership roles emphasise different types and styles of leadership skills" and most often grassroots leaders are able to showcase such leadership abilities because they are engaged in activities which lie within their areas of interest. As a result, an organisation should not always be in a hurry to reward creative personnel with promotions that involve offering them a titled or managerial position, because they may not have all the essential skills required to succeed in such roles. Recognising that leadership can manifest anywhere within the ranks regardless of the office is demonstrated by acknowledging the values delivered at basic levels rather than forcing candidates into positions that do not match their skillsets. Creating a sustainable innovative process (Germano 2012, Mosley 2014) requires establishing an environment whereby both the managers and non-supervisors or subordinates are keen to communicate effectively as leaders.

3 Methodology

The research method used to achieve the objectives of the study was a quantitative survey. The research instruments used for the collection of data were questionnaires and interviews. In total, the population comprised 18 library staff of different ranks from FUTMINNA and Baze University. The population used in the study was determined by the size of the library staff employed in both universities and their desire to participate in the study. The participants from FUTMINNA were one Librarian I, three Librarian II, and two Higher Library Officers, while those from Baze University, Abuja were three Library II, five Assistant Librarians, two Graduate Librarians and two Library Assistants. Ethical matters were considered during the administration of the research instruments as well as in the analysis of the data and they included the following: getting the consent of each of the respondents who participated in the research; concealing the identity of the participants during the final analysis of the study; and acknowledging the author(s) of the journals and books that were consulted. The study was conducted on a small scale within the context of two universities in the mid-northern region of Nigeria. The choice of institutions used for the study was determined by their proximity to the researcher. Consequently, it is difficult to generalise based on the findings of this study.

4 Results

In addition to stating their job titles as presented above, respondents from FUTMINNA and Baze University specified their job roles as either supervisory or non-supervisory; it is on this basis that they were categorised in order to satisfy the objectives of the study. Findings from the data are analysed and discussed below using a thematic approach.

4.1 Job roles and leadership styles

In order to identify the leadership approach the respondents perceived as being practiced in their university libraries, they were asked to make multiple selections from the different leadership styles presented on the questionnaire. The data in Table 1 shows that, in both institutions, the most selected option was a managerial leadership style; Baze with five (45.45%) and FUTMINNA with four (66.67%). This was followed by the autocratic leadership style which was selected by three respondents from Baze University (27.27%) but by no one at FUTMINNA. Table 1 shows that the only selection made in the non-managerial category was made by one of the respondents from Baze University. Few of the respondents from either institution selected transformational and participative leadership styles.

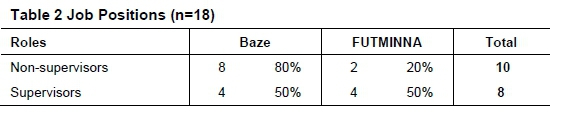

The information in Table 2 shows the proportion of the respondents in supervisory and non-supervisory positions from each institution. Eight of the non-supervisory library staff work at Baze University, while the remaining two are at FUTMINNA. The number of respondents who indicated that their job involves supervising other staff is the same in both universities (four).

4.2 Leadership outside the context of management

Table 3 reveals that a good proportion of the respondents in both supervisory and non-supervisory positions strongly agree that leadership is separate from management (four respondents in each category, translating to 40% of non-supervisors and 50% of supervisors). Three (30%) of the respondents in non-supervisory roles neither agreed nor disagreed with the sentiment that leadership is separate from management, while one of the non-supervisors and two (25%) of the supervisors strongly disagreed.

As shown in Table 4, in response to the statement, In your institution employees can only influence while holding a titled leadership position, six (50%) of the respondents from Baze University indicated that they strongly agreed or agreed with the sentiment. The responses of the other 50% is spread across disagree (three), strongly disagree (one), and neither agree nor disagree (two). Similarly, 50% (three) of the respondents from FUTMINNA indicated that they either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement. The other 50% responded by indicating that they disagree (two) or neither agree nor disagree (one).

4.3 Staff influence by rank

Table 5 reveals that, in response to the statement, A librarian regardless of rank can make contributions and identify operational needs, respondents in non-supervisory positions indicated either strong agreement (five; 50%) or agreement (five; 50%). Those in supervisory positions likewise indicated either strong agreement (six; 75%) or agreement (two; 25%).

As shown in Table 6, the areas of library services in which non-supervisors indicated that their input has satisfied user needs are in teaching (eight; 72.72%) and research (three; 27.27%). Those in the supervisory category indicated they make an impact mostly in the areas of teaching (six; 85.72%), with the exception of one who indicated research as his or her area of impact.

Table 7 shows the response to the question, Do you suggest new ideas to your superiors and colleagues? The response of those in the non-supervisor category was mostly occasionally (six; 54.55%), as were those in supervisory positions (three; 42.86%).

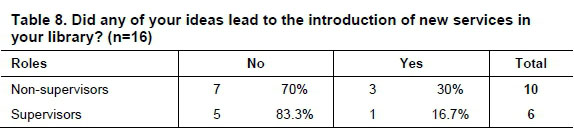

Table 8 shows the responses to the question, Did any of your ideas lead to the introduction of new services in your library? Three non-supervisors (30%) responded Yes, while seven (70%) said No. Supervisors' response for Yes and No was a ratio of 1:5. Two of the respondents in the non-supervisory category stated that the implementation of their ideas helped to improve the speed of users' access and retrieval of relevant information. Another respondent in the same category stated that his idea promoted library resources to users which led to an increase in library patronage.

5 Discussion

As has been shown, the study found that 50% of all respondents indicated that the leadership style being practiced in their university libraries was managerial. These findings coincide with previous research which stated that library leadership approaches are predominantly managerial (Bartlett 2014). Findings also show that representatives from the same institution, Baze University, in particular, selected autocratic and transformational leadership styles too, styles which are opposite in approach and practice. These selections suggest that respondents' perceptions of how they are being supervised could be based on their knowledge of the different leadership styles, on their experiences or on the kind of professional relationships they have with their superiors. Nevertheless, the research shows that more than 50% of the respondents in both supervisory and non-supervisory positions have the understanding that leadership is separate from management and all the respondents either strongly agreed or just agreed that library staff, regardless of rank, can display leadership attributes required to meet organisational objectives. Furthermore, the respondents in both ranks indicated that their jobs have impact in the library, whether they are supervisors or not.

Findings from the study show that library staff in supervisory positions are the most likely to present new ideas to their superiors and colleagues. Few of the librarians in non-supervisory roles indicated they have put forward innovative ideas which have either improved or led to new services for library users. Despite this insight, the study also reveals a disparity in the respondents' opinions about the extent to which one can actually influence without holding a titled leadership position: while half of the total number of respondents from both FUTMINNA and Baze University strongly agreed or agreed with the statement that holding a titled office determines the level of influence one has in one's organisation, the other half either is unsure, disagrees or strongly disagrees.

6 Conclusion

Library leadership is strongly linked to its survival and growth, thus, this study investigated leadership roles in academic libraries and librarians' perceptions of leadership from within the ranks, not just from the top managerial level. Findings show that, although non-supervisory staff can demonstrate leadership attributes, librarians in supervisory positions are most likely to present ideas that influence library services. Creating an organisational culture that encourages innovation where programs and services progressively transform and change depends to a large extent on variations of leadership styles (Jantz 2011). Therefore, for academic libraries in Nigeria to evolve and remain relevant to their users, there is a need to refocus the managerial leadership structure and recognise that leadership can emanate from within the library ranks. Innovative librarians, regardless of rank or stage in the professional journey, who are able to demonstrate leadership in services, programs or activities as described by Dewey (1998) should be acknowledged and encouraged to develop and showcase their skills, proffer new ideas and influence other colleagues. There is a need to conduct further research that will bring to light what librarians at the entry or mid-level of their careers have accomplished on behalf of their library users or institutional body.

References

Aiyebelehin, J.A. 2012. General structures, literatures, and problems of libraries: revisiting the state of librarianship in Africa. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 832. [Online]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/832 (17 August 2018). [ Links ]

Allner, I. 2008. Managerial leadership in academic libraries: roadblock to success. Library Administration & Management, 22(2), 69-78. DOI:10.5860/llm.v22i2.1717. [ Links ]

Anderson, E. 2013. Twenty-one quotes from Henry Ford on business, leadership and life. Forbes. 31 May. [Online]. https://www.forbes.com/sites/erikaandersen/2013/05/31/21-quotes-from-henry-ford-on-business-leadership-and-life/#1982ef3e293c (12 September 2018).

Bartlett, J.A. 2014. The power deep in the org chart: leading from the middle. Library Leadership & Management, 28(4): 1-5. DOI:10.5860/llm.v28i4.7091. [ Links ]

Cawthorne, J.E. 2010. Leading from the middle of the organisation: an examination of shared leadership in academic libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 36(2): 151-157. DOI:10.1016/j.acalib.2010.01.006. [ Links ]

Deakin University. 2018. What is leadership? Future Learn. [Online]. https://www.futurelearn.com/degrees/deakin-university/leadership-professional-practice (17 August 2018).

Dewey, B.I. 1998. Public services librarians in the academic community: the imperative for leadership. In Leadership and Academic Librarians. T.F. Mech and B.G. McCabe, Eds. Westport: Greenwood. 85-97.

Germano, A.M. 2012. Library leadership that creates and sustains innovation. Library and Leadership Management, 25(1): 1-15. [Online]. https://journals.tdl.org/llm/index.php/llm/article/view/2085/2958 (8 September 2018). [ Links ]

Goulding, A. and Walton, J.G. 2014. Distributed leadership and library service innovation. In Advances in Librarianship. A. Woodsworth and W.D. Penniman, Eds. Bingley: Emerald. 37-81. [ Links ]

Harris-Keith, S.C. 2016. What academic library leadership lacks: leadership skills directors are least likely to develop, and which positions offer development opportunity. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(4): 313-318. DOI:10.1016/j.acalib.2016.06.005. [ Links ]

Hernon, P. 2007. Academic librarians today. In Making a Difference: Leadership and Academic Libraries. P. Hernon and N. Rossiter, Eds. Westport: Libraries Unlimited. 1-10. [ Links ]

Iannuzi, A.P. 2014. Leadership in action: leading, learning, and reflecting on a career in academic libraries. Paper presented at CARL 2014 Leadership in Action. 4-6 April 2014. San Jose, CA.

Janes, J. 2014. Leading from all sides. American Libraries: The Magazine of the American Library Association. March/April 2014. [Online]. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2014/04/08/leading-from-all-sides/ (20 December 2019].

Jantz, R.C. 2011. Innovation in academic libraries: an analysis of university librarians' perspectives. Library & Information Science Research, 34(1): 3-12. DOI:10.1016/j.lisr.2011.07.008. [ Links ]

Jerome, I. 2018. An investigation on the nexus between leadership style and job satisfaction of library staff in private university libraries South-West, Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 1677. [Online]. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1677 (17 August 2018). [ Links ]

Lubans, J. 2010. Leading from the middle and other contrarian essays on library leadership. California: Greenwood Publication. [ Links ]

Maxwell, J. 2005. The 360 Degree Leader: Developing your influence from anywhere in the organization. Nashville: Thomas Nelson. [ Links ]

Mosley, P.A. 2014. Engaging leadership: Leadership writ large, beyond the title. Library Leadership & Management, 28(2): 1-6. [Online]. https://journals.tdl.org/llm/index.php/llm/article/view/7061 (03 September 2018). [ Links ]

Northouse, P.G. 2013. Leadership: Theory & Practice. 6th ed. Los Angeles: Sage publications. [ Links ]

Stephens, D. and Russell, K. 2004. Organizational development, leadership, change, and the future of libraries. Library Trends, 53(1): 238-257. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/1727. [ Links ]

Topping, P. 2002. Managerial leadership. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Townley, C.T. 2003. Will the academy learn to manage knowledge? Educause Quarterly, 26(2): 8-11. [ Links ]

Townley, C.T. 2009. The innovation challenge: Transformational leadership in technological university libraries. IATUL Proceedings. 1-4 June 2009. Leuven: Purdue University.

Ugwu, C.I. and Okore, A.M. 2019. Transformational and transactional leadership influence on knowledge management activities of librarians in university libraries in Nigeria. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science. DOI:10.1177/0961000619880229.

Received: 9 July 2019

Accepted: 25 November 2019