Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science

On-line version ISSN 2304-8263

Print version ISSN 0256-8861

SAJLIS vol.84 n.2 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7553/84-2-1767

RESEARCH ARTICLES

A multivariate analysis of the determinants for adoption and use of the Document Workflow Management System in Botswana's public sector

Olefhile MosweuI; Kelvin Joseph BwalyaII

IDoctoral candidate in the Department of Information Science, University of South Africa, olfmos@gmail.com ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4404-9458

IIVice Dean: Research, Innovation and Internationalisation (College of Business & Economics), University of Johannesburg, South Africa. kbwalya@uj.ac.za ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0509-5515

ABSTRACT

Governments in Africa are spending significant funds in their drive towards putting public business processes and services online. Although this drive has different names, such as electronic government (e-government), open government and open data, the motivation is hinged upon achieving overall efficiency and effectiveness in public services and is based on the notion of freedom of information. In Botswana's public services, diverse interventions are being put in place to facilitate business automation and electronic records management. The then-Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI), now Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry (MITI), has joined the drive by implementing the Document Workflow Management System (DWMS) as an e-records management system. This study probes the determinant factors influencing meaningful adoption and usage of the DWMS for effective records and information management within MITI. Multivariate analysis is employed to understand which factors have the highest variance in adoption and use of the DWMS. The study utilises the adapted Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) as the conceptual framework in its design. Quantitative data was collected from a population of sixty-one officers, from which fifty-three (86.9%) responses were received and included in the analysis. Effort expectancy, behavioural intention, social influences and facilitating conditions were the key determinants for adoption and use accounting for 55% of variance. The study identifies to what degree each of the potent factors contribute to adoption and use of the DWMS at MITI. The major limitation of this study is that it was impossible to identify all the factors influencing behaviour intention, as human behaviour is difficult to measure. Other unidentified factors account for 45% of variance not accounted for by the predictor factors. This is an indication that there is a need for an in-depth study, preferably a longitudinal study, that critically probes the factors of technology adoption in work processes by a large set of individuals in a developing world context.

Keywords: Use, adoption, DWMS, ERDMS, Botswana, e-records, regression analysis, modelling

1 Introduction

The integration of technologies in the different public service business processes in Botswana has prompted many parastatal and government departments to consider seriously electronic records management strategies. As a result, many of these organisations are implementing different types of electronic document and records management systems. In the context of Botswana, the integration of electronic records (e-records) management in the public sector poses many challenges, such as low adoption and underutilisation (Kalusopa & Ngulube 2012; Mosweu, Bwalya & Mutshewa 2016). This research posits that the understanding of the factors at the centre of low adoption and underutilisation of an electronic document and records management system (EDRMS) is cardinal to ensuring that there is enhanced adoption of e-records utilisation in the Botswana public sector. Further, the understanding of factors influencing the adoption and utilisation of an EDRMS is important given the significant sums of money that are spent in procurement of records management systems, necessitating that there exists not even the slightest chance of their absolute failure.

There has in the past generally been low adoption and use of information systems in public sectors in Africa (Kipsoi, Chang'ach & Sang 2012; Zaied 2012; Akande & van Belle 2014). Low adoption entails that many benefits are missed, and the intended purpose of a technology is not met. For example, low adoption of an EDRMS entails that public organisations miss out on a number of benefits, which can be harnessed in the realm of improving the effectiveness of public service delivery. Some of these missed opportunities include the following: quicker completion of tasks; streamlined business processes and automated workflows; reduced efforts in compliance with legislation or records management principles; quicker information retrieval for decision-making processes; better management of diverse information resources; greater access control and security over classified information; controlled disposal of corporate information; and dynamic audit controls (National Archives of Australia 2011; Ojo & Grand 2011). Given the multi-dimensional nature of technology adoption and usage, low adoption is entrenched in a diverse range of factors influencing the individual, the organisation and the environment in which technology is introduced (Banderker & van Belle 2009; Singh & Punia 2011; Zaied 2012; Akande & van Belle 2014). A comprehensive understanding of factors influencing low adoption and underutilisation of an EDRMS involves a careful analysis of factors pertinent to each of the three layers: individual, organisation and environment. This study intends to understand the factors that are at the centre of low adoption and utilisation in the case of the Botswana public sector, focusing on the individual level.

There is a dearth of studies that have investigated individual factors influencing technology adoption in the developing world contexts, despite this being a hot topic in the global north (Zaied 2012; Akande & van Belle 2014). Jain and Mutula (2001) and Iyanda and Ojo (2008) conducted exploratory studies in Botswana, investigating technology adoption in the public sector and pinpointed factors such as limited management support and resistance to change, lack of awareness, and lack of training and computer skills as some of the reasons for low adoption. Like the studies above, studies conducted in Qatar, South Africa, Uganda and India have only identified general factors influencing adoption and use of a document workflow management system (DWMS) (Al-Shafi & Weerakkody 2009a; Banderker & van Belle 2009; Singh & Punia 2011). Globally, the general challenges influencing individual adoption of technology have revolved around limitation in Information and Communications Technology (ICT) skills, lack of support infrastructure, unawareness of technology platforms, resistance to change, cultural barriers and lack of support (Munetsi 2011; Akande & van Belle 2014; Mutimba 2014; Ambira 2016). Although there are countless studies explaining adoption and usage of technology at the individual level, many studies have utilised the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). Using the UTAUT as the theoretical lens, this study investigates the determinants of DWMS (synonymous with EDRMS) adoption and use, specifically focusing on line managers who are the custodians of DWMS usage and integration in the business processes. The study is important because it has the potential to guide the implementation of a DWMS in contextually similar environments.

2 Background

DWMSs or EDRMSs have been implemented in many parts of the world to improve records management or information integration into business processes with a goal to improving organisations' efficiency and effectiveness (Queensland State Archives 2010; Mosweu 2012; Mutimba 2014). Globally, many organisations have been motivated to implement an EDRMS owing to their many advantages. An EDRMS enforces security in government document handling processes which culminates in enforcement of accountability in government business processes (National Archives of Australia 2011). When successfully implemented, an EDRMS provides timely information with a high degree of accuracy without a significant cost. It is worth noting that an EDRMS is not only a data management and archiving platform, but also integrated organisation-wide knowledge management systems acting as fuel for organisational market participation trend analysis, integrated decision-making and an information repository for strategic discourse (Mutimba 2014; Ambira 2016). Therefore, it can be posited that an EDRMS is a critical aspect of organisations' competitive advantage and long-term survival (Haider, Aryati, & Mahadi 2015). EDRMSs have been used to check document flow within government entities, thereby giving a sense of business processes operations and overall efficiency (Abdulkadhim et al. 2015a). For example, the Document Management and Electronic Archiving (DOMEA) system implemented in Germany aimed to achieve a paperless environment in the three levels of government operations. The DOMEA's modular structure comprises documents, records and files (Kunis, Rünger, & Schwind 2007).

EDRMSs, in their different forms such as DWMS, have been implemented the world over but few studies have attempted to understand the factors that influence the successful implementation in government departments (Abdulkadhim et al. 2015a). The majority of studies on implementation have concentrated on understanding factors influencing EDRMS adoption at early stages. Several factors, both technical and managerial, have been identified to impact on DWMS implementations and the prominence of these factors varies according to context. After recognising some challenges in implementation, New Zealand designed its EDRMS with user-friendly interfaces so that individuals could easily adopt the interventions (Yin 2014). Yin (2014) further posits that senior management support in EDRMS interventions may go a long way in influencing the early adoption of EDRMS platforms and, effectively, their usage. The analysis of the implementation of EDRMSs in South Africa showed that socio-technical factors, inadequate capacity and computer anxiety prevented individuals from appropriately adopting and utilising an EDRMS in the Eastern Cape (Munetsi 2011). Ambira (2016) investigated the challenges of implementing an EDRMS at different levels of Kenya's public sector. The study found that individual adoption of an EDRMS, and therefore e-records, is limited due to multi-dimensional factors that negatively affect individuals' adoption and utilisation of e-records. In the Kingdom of Eswatini (Swaziland), an EDRMS is planned to be implemented for the first time in 2019, with technical and managerial preparations currently underway (International Cooperation and Development Fund 2016). Understanding factors influencing EDRMS implementation needs to include the time factor to understand how the effects of these factors evolve over time. Factor exploration to harness factors as predictor variables to a given phenomenon is largely a static endeavour unlike a desired dynamic one (Abdulkadhim et al. 2015a).

Generally, successful EDRMS implementation depends on a careful synthesis of supporting technological (hardware and software design, security, access platform design, data quality, security), organisational (procedures, processes, rules and regulations) and user factors (culture, drivers, barriers, training and capability, resistance to change) (Kwatsha 2010; Yin 2014; Mosweu 2016). A robust measurement of what factors are the most critical in the implementation of an EDRMS would assist in understanding the contribution brought about by each of the individual factors (Haider et al. 2015). Although this is the case, it is worth mentioning that the central tenet of meaningful adoption and use of technology depends on individuals (Isaac, des Horts & Leclercq 2006; Radu 2016).

Another important factor influencing EDRMS adoption and use is the way in which implementation is approached. For example, with a goal to achieve excellence in information management and governance, the global leader of e-government services, South Korea, implemented an EDRMS using integrated portal websites providing a ubiquitous and integrated information service to its citizens and businesses (Abdulkadhim et al. 2015b; Ambira 2016). Implementation of an EDRMS is a pre-requisite to meaningful e-government implementation. Migration into more efficient web-based systems from traditional government systems without critically considering contextual nuances and re-engineering current business processes is a risky undertaking (Hassan, Shelab, & Peppard 2011).

3 EDRMS implementation in Botswana

As the anchor department in the Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry (MITI) of Botswana, the Department of Corporate Services is responsible for a spectrum of tasks within the ministry's mandate. MITI is implementing a DWMS to manage e-records and therefore is central to process automation and integration in a dynamic information environment. The ministry has implemented the Government Accounting and Budgeting System to manage accounting processes, the Computerised Personnel Management System for staff management and the Ministry of Trade and Industry Information Management System for the registration of businesses, coordinating competition among industry players, and facilitating Botswana's participation in international trade, in addition to the DWMS. Of these, the DWMS is central to e-records management and therefore central to process automation and integration. Although implementation of DWMS has been ongoing since 2008, the Action Officers who are at the centre of DMWS implementation most often opt to ignore it, culminating in overall underutilisation (Consult IT 2012). The case in point evidently shows that the DWMS has been adopted at institutional level but ignored at the individual level making its ultimate adoption difficult. For this particular context, therefore, there is a need to understand the inherent factors that have nurtured this underutilisation.

4 Theoretical framework

Studies on the adoption and use of diverse information and communication technologies (ICTs) across a whole spectrum of organisational functions in both the private and public sector have been undertaken in Africa using various technology adoption models (Kilangi 2012; Akande & van Belle 2014; Murgor 2015). These include the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Venkatesh et al. 2003). Such studies have covered a number of areas such as student utilisation of computer information retrieval systems in an academic library at the University of Ghana (Boakye 2015), the adoption of mobile money usage by customers of SMEs in Uganda (Mugambe 2017), acceptance of e-prescribing technology by South African physicians (Cohen, Bancilhon & Jones 2013), determining factors for the adoption of an EDRMS in the public sector of Malaysia (Aziz et al. 2017), an assessment of the adoption of ICTs in Kenyan public universities (Chumo & Kessio 2015), highlighting the determinants of user adoption of e-government services in Greece and the role of citizens (Voutinioti 2013) and the likelihood of computer adoption by school principals in Botswana (Totolo 2007). The use of UTAUT to explain technology adoption and use is thus widely spread across disciplines in different countries, both developing and developed.

According to the UTAUT model, effort expectancy, performance expectancy, social influences and facilitating conditions are determinants of the intention to use technology at the individual level (Venkatesh et al. 2003). The following are some of the factors that globally define individuals' motivation to adopt technology, which were subsequently turned into research objectives in this study:

• Effort expectancy is defined as the degree to which technology is perceived to be easy to use. The easier the technology is to use, the more it is embraced. Technologies have been rejected because of the perception that it would be difficult to use them. For example, Behrens et al. (2005) studied factors that contributed to the success of an online assignment submission system used by distance learners in an Australian academic institution. Students who were technologically savvy found the system easy to use, adopted and used it while their counterparts found it difficult to use, and were less keen to use it.

• Performance expectancy is defined as the degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help him or her to attain gains in job performance. As an objective, respondents were to state from a number of options, the extent to which they viewed the DWMS as an EDRMS that would assist them to better carry out their day to day duties. An adopted technology is normally deployed to improve job performance. However, if it turns out that the deployed technology makes job performance a difficult undertaking, they tend to reject it (Orlikowski 2000; Rogers 2003). Calisir and Calisir (2004) explored perceived usefulness of technology as a factor in the adoption of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) by end users. The end users were from a wide range of positions in manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, telecommunications and consulting. The purpose of the study was to examine the influence of interface usability characteristics, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use on end user satisfaction with ERP. Perceived usefulness of technology was found to be the best predictor of end user satisfaction with information systems. Facilitating conditions are referred to as the degree to which individuals perceive that organisational and technical infrastructure support system usage (Venkatesh et al. 2003). They include user training and communication. In a study by Di Biagio and Ibiricu (2008) that analysed and shared the experience of implementing an EDRMS at the European Central Bank in Germany by identifying what went well and what could have been done better, it emerged that successful EDRMS implementation benefited from project management and communication. The researchers concluded that management support and communication eased worries brought on by new systems, thereby countering user resistance. In this study, respondents were asked whether the organisation's work environment has prepared the ground, including the availability of technical equipment, for the adoption and use of the DWMS.

• Social influences refer to "the degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe he or she should use the new system" (Venkatesh et al. 2003:451). Mazman, Usluel, and Cevik (2009) have described the same concept as social factors. According to Zeal, Smith and Scheepers (2010:2), social influences "encompass both how an individual can effect attitude and behaviour change in others, and how individuals are influenced by the attitudes and behaviour of other people." They include the influence of experts, mass media reports, word of mouth from superiors, friends and colleagues. Social influence has been found to be a good predictor of the acceptance of information technology by healthcare professionals (Yi et al. 2006; Ifinedo 2012).

UTAUT is made up of four moderating factors namely gender, age, experience and voluntariness. For this study, voluntariness as a moderating factor was excluded as DWMS is neither compulsory nor voluntary. Experience was also left out as this study is cross-sectional while the original UTAUT study was longitudinal (Venkatesh et al. 2003). A modified UTAUT made from a synthesis of eight different models was used as a theoretical framework. The models were:

• The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), which was drawn from social psychology. It is one of the influential theories of human behaviour. The construct, subjective norm, was adopted for the study (Fishbein & Ajzen 1975).

• The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which was used to predict information technology acceptance and usage on the job in an information systems environment. The constructs adopted were the perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of technology (Davis 1989).

• The Motivational Model from which literature in psychology has supported general motivation theory as an explanation of behaviour. The adopted construct, extrinsic motivation, posits that users of technology would perform an act "because it is perceived to be instrumental in achieving valued outcomes that are distinct from the activity itself, such as improved job performance, pay, or promotions" (Davis, Bagozzi & Warshaw 1992: 1112).

• The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), which extended TRA by adding the construct of perceived behavioural control that is similar to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing some behaviour (Ajzen, 1991).

• Combined TAM and TPB, which combined the predictors of TPB with perceived usefulness from TAM (Taylor & Todd, 1995). The adopted constructs were subjective norm, perceived usefulness and attitude toward behaviour.

• The Model of PC Utilisation that is suitable to predict individual acceptance and use of a range of information technologies. The adopted constructs were facilitating conditions, complexity, job fit and social factors (Venkatesh et al. 2003).

• Innovation Diffusion Theory that has been used by Rogers (1995) to study individual acceptance of technology. The constructs adopted for the study were relative advantage, ease of use, compatibility and results demonstrability (Venkatesh et al. 2003).

• The Social Cognitive Theory, which has been applied to the context of computer utilisation. The adopted constructs were anxiety, self-efficacy and outcome expectations (Venkatesh et al. 2003).

The UTAUT was chosen owing to its wider usage, viability and stability in similar studies in similar research contexts to the current study (AlAwadhi & Morris 2008; Sykes, Venkatesh & Gosain 2009; Al-Shafi & Weerakkody 2009b; Khan et al. 2012; Alrawashdesh 2011; Barua 2012; Alshehri et al. 2012). However, there was a need to adapt it somewhat to ensure that the unique contextual characteristics were taken into consideration. The conceptual outlay of the UTAUT is shown in Figure 1. The moderating factors 'experience' and 'voluntariness' are not included as it is mandatory for all Action Officers to use the DWMS at MITI. Longitudinal studies mostly consider 'experience' as one of the constructs but this is not desired when the study is cross-sectional like the current one. The constructs in Figure 1 were included in the data collection instruments.

5 Methodology

Although complemented with some interviews with individuals purposively identified, the main data collection point was the questionnaire that was adapted from the originators of the UTAUT Model (Venkatesh et al. 2003). Some limited questions were open ended and the study population comprised of sixty-one officers. A census survey design was thus preferred in line with Yount (2006) who stated that when the study population is fewer than 100 potential participants, all of them should be selected. The principal respondents were the Action Officers and Line Officers based at MITI headquarters in Gaborone. For questionnaires, out of sixty-one distributed, fifty-three (86.9%) were returned and included in the analysis.

6 Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analysis was performed on the dataset in order to determine the extent to which each of the factors in the UTAUT model predicted behavioural intention to adopt a DWMS. The next section presents an analysis of results obtained from the analysis.

6.1 Pre-tests

The research began with understanding of whether each of the actors espoused in the adapted UTAUT model followed statistical significance, validity and normality so that all statistical methods applied on the dataset qualify for statistical inference. The nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were used in testing whether the dataset followed accepted normal distribution. Because the study's dataset was initially unstandardised, it was standardised and compared with the probability density function (standard normal distribution). After statistical testing, the data fitted into the bell-shaped Gaussian distribution, demonstrating normality and readiness for further statistical use. Therefore, it was appropriate to draw statistical inferences from the dataset as the data was obtained from normally distributed samples (Ghasemi & Zahediasl 2012). The results of the two tests are shown in Table 1.

Further, the results revealed that the data was statistically significant, justifying its statistical readiness. In order to understand the inter-correlations between variables, the Pearson correlation was utilised. In all the cases, the skewness coefficients were less than their standard errors meaning that the dataset was normally distributed and ready to be used in the analysis. The dataset showed a weak negative correlation r=0.2 between performance expectance and effort expectance and between social influences and effort expectance which are consistent with what would be expected in real life situations - the more effort to use a system, the less performance is expected of that system. The results further revealed that the empirical data was significant at level 0.05 (p<0.05) giving more basis to reject the null hypothesis and rely on the UTAUT variables in the understanding of the key factors influencing adoption.

6.2 Empirical results

The results of the study were considered in line with each of the constructs from the UTAUT deemed relevant given the context of the study as follows:

6.2.1 Effort Expectancy (EE) in using the DWMS

It was important to understand the experiences advanced by first-time users of the DWMS with regard to the effort needed to learn to use the system. An overwhelming 98.1% of the individuals in the study mentioned that the system was easy to use and that interaction with the DWMS was clear and understandable; 1.9% remained neutral. All respondents agreed that developing skills for first-time users of the system is easy. Given the above, it is easy for the DMWS to be integrated into MITI's business processes. The study results have highlighted findings from other studies that an easy-to-use system stands a higher chance of being adopted by users (AlAwadhi & Morris 2008; AbuShanab, Pearsony, & Setterstrom 2010; Bugembe 2010: Bwalya 2011: Barua 2012: Alshehri et al. 2012).

6.2.2 DWMS Performance Expectancy (PE)

PE articulates the extent to which individuals assume that utilisation of technology in their everyday work processes will improve job performance (Venkatesh et al. 2003). A total of 93.4% of the respondents believed that using the DWMS would enable them to accomplish tasks easily, reduce time spent on doing routine tasks and generally make their jobs easier. PE is a big motivation factor for technology adoption as espoused in other studies in Saudi Arabia, Botswana and South Africa (Alshehri et al. 2012; Totolo 2007; Seymour, Makanya & Berrange 2007).

6.2.3 Facilitating Conditions (FC) at MITI

FC are a set of all possible incentives and initiatives put in place to create a conducive environment to facilitate enthusiastic adoption and use of technology platforms in everyday work processes. In contrast to what was generally posited, 45.2% of the respondents indicated that they do not feel that they have the necessary knowledge to use the DWMS. These respondents indicated that there was adequate user support for individuals facing problems with the DWMS. Individuals with obvious challenges are offered training opportunities to enhance their usability. As posited in other studies, FC have a greater impact on behavioural intention to adopt and use a technology (Di Biagio & Ibiricu 2008; Yusof & Ramayah 2011; Ghalandari 2012; Taiwo & Downe 2013). In Australia, would-be users of the EDRMS were empowered using appropriate training before the system went live, and, in the UK, prior training of the end users increased the likelihood of system adoption and usage (Maguire 2005; Wilkins, Swatman & Holt 2009).

6.2.4 Social Influences (SI), gender and age

Many individuals at MITI were attentive to what others thought about using the DWMS. Although 47% disagreed being influenced by others to adopt and use the DWMS, 45% agreed that influential people at MITI had an impact on their adoption and usage of the DWMS. One striking outcome of the empirical study was that most senior executives at MITI did not directly support the adoption and use of the DWMS as posited by 72% of the respondents. The impact of SI on overall adoption and use of newly introduced technology was also cited as a key factor influencing behavioural intention in the adoption of mobile learning in Taiwan and internet banking in Jordan (AbuShanab, Pearsony, & Setterstrom 2010; Chen, Li, and Li 2011). In the context of MITI, gender and age had a negligible effect on the adoption and use of the DWMS. For gender, the study has shown that ten out of twenty (50%) of male respondents agreed that their behavioural intention to adopt the DWMS was influenced by social factors. An equal number (50%) showed the opposite. This suggests that gender has a more or less equal moderating effect on the adoption of a DWMS. As for age, the results of the study indicated that 39.1% of the respondents aged between thirty-one and forty years affirmed that social influences related to the adoption of the DWMS moderated their behavioural intention to adopt the DWMS while a greater number (56.5%) disagreed. Furthermore, ten (50%) respondents with an age range of between forty-one and fifty years agreed that social influences moderated their behavioural intention to adopt the DWMS. The same number, in the same age category, disagreed. It would seem that age is neither a good nor a bad moderator of behavioural intention to adopt the DWMS by Action Officers and Records Officers.

6.2.5 Behavioural Intention (BI)

Despite some challenges pointed out by the respondents, 74% indicated that they had the intention to use the DWMS in the near future. The willingness of the Action Officers and Records Officers to adopt and use the DWMS now or in the future is an indication that there is chance that the DWMS can be adopted and used universally at MITI if current challenges limiting usage are overcome.

The empirical results have shown that each of the UTAUT constructs have some impact on the overall degree of adoption and use of the DWMS. In order to quantify the variance of each of the factors, a linear estimation model from the sum of squared residuals was modeled.

6.3 Linear estimation model

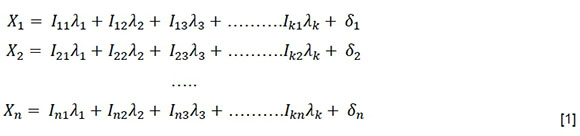

In order to understand which factors/variables are at the centre of contributing the highest variance to the causes of effective adoption and use of the DWMS, there was a need to model the effect of the identified factors to the real situation. To do so, the identified variables were plotted against the expected projectile of the real factors. The variables were identified using in-depth thematic analysis and can be presented using linear combinations of measured variables represented using equation [1]:

where X1, X2 and Xn are known variables, õy is the jth factor, and Ay is a constant representing the ith and jth factor (δ represents uncertainty).

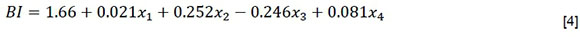

From the linear regression [1], the least squares estimator (LS/E) with respect to the sum of squared residuals is represented by equation [2]:

where x is the independent variable or explanatory or covariate variable, b1 is the estimated intercept and b2 is the estimated slope coefficient.

The least squares estimator is the basis for the understanding of the contribution of the variance, which is represented by the totality of the R-squared variables, measured in this study. The linear estimation model fits the study's dataset with a quadratic equation (refer to equation [2]). In this research, multiple regression is denoted using β1 and β2 rather than b1 and b2. The final linear equation estimating the residual (the difference between the fitted dependent variable and the dependent variable - modelling the outliers in the multivariate sample) takes the general form with systemic and random variables:

The systemic variables are defined from the dataset and the random variables may take unknown values not explained by the predictor variables (co-variables). Equation [3] is the basis for multiple linear regression at the centre of this study.

7 Research implications

The data was checked to ensure that all the negative outliers were removed. The key results from Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) on the dataset are presented in Table 2.

R squared (R2) shows the degree of variance accounted for by each of the factors. In line with the empirical results shown above, performance expectance is the highest predictor variable accounting for the highest variance (16.1%) in adoption and use of the DWMS at MITI. Effort expectance with R2 = 10.3% has the lowest variance. The total variance contributed by all the predictor variables or factors is 55%.

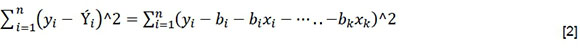

Standardised coefficients, representing how many standard deviations of dependent variables will change per standard deviation increase/decrease in the predictor variable, was therefore desired. Standardised regression coefficients obtained from the multiple regression procedures standardised to ensure that the variances between the dependent (identified variables) and the independent (BI) variables is one, are shown in Table 3. The data in Table 3 show that the unstandardised coefficients indicate that the dataset has p-values greater than 0.05 (statistical significance) and therefore does not provide a good fit for the data. Therefore, it was necessary to do data fitting using least squares estimation as shown in Equation [4] below:

The linear estimation model is used as a computationally convenient measurement of fit of the modelled variables and the reality that it attains in real world actual situations. From Equation [3], the Linear estimation model, which is the wellness-of-fit and the model equation from the study's dataset using the standardised coefficients, will take the following form:

Equation [4] shows a linear regression between the dependent variable (BI) and the covariate/systemic variables providing justification for the identified factors explaining adoption and usage of the DWMS by different individuals at MITI. The model equation [4] takes a linear projectile confirming the importance of each of the identified co-variables in influencing DWMS adoption and usage. Other than the factors espoused in the model equation above, the empirical study has identified computer anxiety and compatibility of the DWMS as additional factors that influence the decision whether to adopt and use the DWMS.

One of the limitations based on the study results is that the implication of the factors articulated in this study are a snapshot of what matters most at this point in time. However, the dimensions of these factors might change in time, given the turbulent contextual settings of the study area. Despite this being the case, it provides important pointers towards successful design and implementation of a DWMS (an EDRMS) in contextually similar environments within a space of ten or more years. Future studies need to explore the possibility of longitudinal studies which can have a more rounded articulation of the intra- and inter-linkages among the factors explored and their impact on overall successful implementation of technology platforms in business processes.

In order to inculcate the dynamism in DWMS implementation, this study espouses a rigorous change in management strategy when implementing the DWMS, which will manage the changing dimensions of ICT integration into the different organisations' business processes. This strategy has two components: individual change management and organisational change management coupled with overarching common factors as articulated in Abdulkadhim et al. (2015b). In this study, issues such as level of bureaucracy at MITI, availability of a competent human resource base to implement the DWMS, and technical capability were taken to be constant and negligible.

8 Conclusion

This paper intended to understand what factors influence the adoption and usage of a DWMS and further probed to what extent each of these factors contributed to the total variance as individual predictors. The study was motivated by the fact that MITI had implemented a DWMS a long time ago but a recent probe into its usage proved that usage was low and, in many instances, non-existent. The opportunity cost paid for ignoring adoption and usage of the DWMS is big, given the many benefits that come with EDRMS implementation on e-record management capability, information integration and overall business efficiency and effectiveness. The dependent variable determining the level of willingness of the individual to adopt and use a DWMS is modelled using behaviour intention. The predictor factors from the adapted UTAUT account for a 55% variance in behavioural intention to adopt and use the DWMS at MITI. The major implication of this study is that the UTAUT's degree of precision in measuring technology adoption and use is not as high as reported in certain developing world contexts.

The major limitation of this study is that it was impossible to identify all the factors influencing behaviour intention, as human behaviour is difficult to measure. The other unidentified factors accounted for 45% of variance not accounted for by the predictor factors. This is an indication that there is a need for an in-depth study, preferably longitudinal, unlike a cross-sectional study like this one that critically probes the factors of technology adoption in work processes by a large set of individuals in a developing world context. Such a study would propose a requisite extension of the UTAUT towards a global model of measuring technology adoption and use with higher predictive capacity. Since this study was done at one government department, it is not representative of all government ministries in Botswana.

This study offers an opportunity for the extension of the UTAUT to be used in similar developing world contexts. This points to the fact that the UTAUT model is limited in measuring factors influencing technology/system adoption especially in developing world contexts. Consequently, the UTAUT is not as efficient as perceived in explaining the factors influencing technology adoption.

References

Abdulkadhim, H., Bahari, M., Bakri, A. and Hashim, H. 2015a. Exploring the common factors influencing Electronic Document Management Systems (EDMS) implementation in Government. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 10(23): 17945-17952. [ Links ]

Abdulkadhim, H., Bahari, M., Bakri, Z. and Ismail, A. 2015b. A research framework of electronic document management systems (EDMS) implementation process in government. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 81(3): 420-432. [ Links ]

AbuShanab, E., Pearsony, J.M. and Setterstrom, A.J. 2010. Internet banking and customers' acceptance in Jordan: the unified model's perspective. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 26(23): 1-35. [ Links ]

Akande, A.O. and van Belle, J.P.W. 2014. ICT adoption in South Africa: opportunities, challenges and implications for national development. Paper presented at the IEEE International Conference on Electronics Technology and Industrial Development. 23-24 October 2013. Bali, Indonesia.

AlAwadhi, S. and Morris, A. 2008. The use of UTAUT model in the adoption of e-government services in Kuwait. Proceedings of the Hawaiian International Conference on System Sciences. 7-10 January 2008. Waikoloa, Hawaii: DOI:10.1109/HICSS.2008.452.

Alrawashdesh, T.A. 2011. The extended UTAUT acceptance model of computer-based distance training system among public sector's employees in Jordan. D.Phil thesis. University of Malaysia. [Online]. http://etd.uum.edu.my/2798/2/1.Thamer_A._Alrawashdeh.pdf (15 January 2018). [ Links ]

Al-Shafi, S. and Weerakkody, V. 2009a. Factors affecting e-government adoption in the state of Qatar. Paper presented at the European and Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems. 12-13 April. Abu Dhabi, UAE. [Online]. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.426.7576&rep=rep1&type=pdf (10 January 2018).

Al-Shafi, S. and Weerakkody, V. 2009b. Understanding citizens' behavioural intention in the adoption of e-government services in the State of Qatar. Proceedings of the 17th European Conference of Information Systems. Verona, Italy: EICS. 1618-1629.

Alshehri, M., Drew, S., Alhussain, T. and Alghamdi, R. 2012. The effects of website quality on the adoption of e-government services: an empirical study applying UTAUT model using SEM. Paper presented at the 23rd Australasian Conference on Information Systems. 3-5 December 2012. Geelong, Australia. [Online]. http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1211/1211.2410.pdf (03 January 2018).

Ambira, C.M. 2016. A framework for management of electronic records in support of e-government in Kenya. PhD thesis. University of South Africa. [Online]. [ Links ]

http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/22286/thesis_ambira_%20cm.pdf?sequence=1 (12 November 2018). Aziz, A.A., Yusof, Z., Mokhtar, U.A and Jambari, D.I. 2017. The determinant factors of Electronic Document and Records Management System (EDRMS) adoption in public sector: a UTAUT-based conceptual model. Paper presented at the 6th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI). 25-27 November 2017. Langkawi, Malaysia. DOI:10.1109/ICEEI.2017.8312413.

Banderker, N. and van Belle, J.P. 2009. Adoption of mobile technology by public health doctors: a developing country perspective. International Journal of Healthcare Delivery Reform Initiatives (IJHDRI), 1(3). DOI:10.4018/jhdri.2009070103. [ Links ]

Barua, M. 2012. E-governance adoption in government organization of India. International Journal of Managing Public Sector Information and Communication Technologies (IJMPICT), 3(1): 1-20. [ Links ]

Behrens, S., Jamieson, K., Jones, D and Cranston, M. 2005. Predicting system success using the technology acceptance model: a case study. Paper presented at 16th Australasian Conference on Information Systems. 9 November-2 December 2005. Sydney, Australia. [Online]. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a827/c7381694c2da2a52e851cf42543c277a30ae.pdf (12 November 2018).

Boakye, G. 2015. Determinants of students' utilisation of computer information retrieval systems in academic libraries: evidence from the University of Ghana or a case study of the University of Ghana. UDS International Journal of Development, 2(2): 61-76. [ Links ]

Bugembe, J. 2010. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude and actual usage of a new financial management system: a case study of Uganda National Examinations Board. MSc thesis. Makerere University. [Online]. http://www.mubs.ac.ug/docs/masters/acc_fin/Perceived%20usefulness.pdf (3 October 2017). [ Links ]

Bwalya, K.J. 2011. E-government adoption and synthesis in Zambia: context, issues and challenges. PhD thesis. University of Johannesburg. [Online]. https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10210/7905/Bwalya.pdf?sequence=1 (5 September 2017). [ Links ]

Calisir, F and Calisir, F. 2004. The relation of interface usability characteristics, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use to end user satisfaction with Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems. Computers in Human Behaviour 20: 505-515. [ Links ]

Chen, S.C., Li, S.H. and Li, C.Y. 2011. Recent related research in technology acceptance model: a literature review. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research, 1(9): 124-127. [ Links ]

Chumo, K.P and Kessio, D.K. 2015. Use of UTAUT model to assess ICT adoption in Kenyan public universities. Information and Knowledge Management, 5(12): 79-83. [ Links ]

Cohen, J.F., Bancilhon, J. and Jones, M. 2013. South African physicians' acceptance of e-prescribing technology: an empirical test of a modified UTAUT model. South African Computer Journal, 50: 43-54. [ Links ]

Consult IT. 2012. Self-assessment report: Document Management Workflow System (DWMS) implemented by CIT and SQL using the KRIS platform. (Unpublished).

Davis, F.D. 1989. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3): 319-340. DOI:10.2307/249008. [ Links ]

Davis, F.D, Bagozzi, R.P. and Warshaw, P.R. 1992. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22: 1111 -1132. [ Links ]

Di Biagio, M.L. and Ibiricu, B. 2008. A balancing act: learning lessons and adapting approaches whilst rolling out an EDRMS. Records Management Journal, 18(3): 170-179. [ Links ]

Fishbein, M and Ajzen, I. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: an introduction to theory and research. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Ghalandari, K. 2012. The effect of performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence and facilitating conditions on acceptance of e-banking services in Iran: the moderating role of age and gender. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 12(6): 801 -807. [ Links ]

Ghasemi, A. and Zahediasl, S. 2012. Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. International Journal of Endocrinology Metabolism, 10(2): 486-489. [ Links ]

Haider, A.A., Aryati, B. and Mahadi, B. 2015. Opportunities and challenges in implementing Electronic Document Management Systems. Asian Journal of Applied Sciences, 3(1): 36-39. [ Links ]

Haider, A.A., Mahadi, B. Aryati, B. and Haslina, H. 2015. Exploring the common factors influencing electronic document management systems (EDMS) implementation in government. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 10(23): 17948-17952. [ Links ]

Hassan, H.S., Shelab, E. and Peppard, J. 2011. A framework for e-service implementation in the developing countries. International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management, 2(1): 55-68. [ Links ]

Ifinedo, P. 2012. Technology acceptance by health professionals in Canada: An analysis with a modified UTAUT model. Proceedings of the 45th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. 4-7 January 2012. Wailea, Maui, Hawaii. IEEE. DOI:10.1109/HICSS.2012.556.

International Cooperation and Development Fund. 2016. Swaziland Electronic Document and Records Management (EDRMS) development project to be launched in Swaziland. [Online].

http://www.icdf.org.tw/ct.asp?xItem=36086&ctNode=29877&mp=2 (12 November 2018).

Isaac, H., des Horts, C.H.B and Leclercq, A. 2006. Adoption and appropriation: toward a new theoretical framework: an exploratory research on mobile technologies in French companies. [Online]. https://halshs.archives- ouvertes.fr/halshs-00155506/document (26 July 2018).

Iyanda, O. and Ojo, S.O. 2008. Motivation, influences, and perceived effect of ICT adoption in Botswana organizations. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 3(3): 211-322. [ Links ]

Jain, P. and Mutula, S.M. 2001. Diffusing information technology in Botswana: a framework for Vision 2016. Information Development, 17(4): 234-239. [ Links ]

Kalusopa, T. and Ngulube, P. 2012. Record management practices in labour organisations in Botswana. South African Journal of Information Management, 14(1): 1-15. [ Links ]

Khan, S.Z., Shahid, Z., Hedstrom, K. and Andersson, A. 2012. Hopes and fears in implementation of electronic health records in Bangladesh. Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, 54(8): 1-18. [ Links ]

Kilangi, A.M. 2012. The determinants of ICT adoption and usage among SMEs: the case of the tourism sector in Tanzania. PhD thesis. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. [Online]. https://research.vu.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/42212437/complete+dissertation.pdf (12 November 2018). [ Links ]

Kipsoi, E.J., Chang'ach, J.K. and Sang, H.C. 2012. Challenges facing adoption of Information Communication Technology (ICT) in educational management in schools in Kenya. Journal of Sociological Research, 3(1): 18-28. [ Links ]

Kunis., R, Rünger, G. and Schwind, M. 2007. A new model for document management in e-government systems based on hierarchical process folders. Electronic Journal of e-Government, 5(2): 191-204. [ Links ]

Kwatsha, N. 2010. Factors affecting the implementation of an electronic document and records management system. MPhil thesis. University of Stellenbosch. [Online]. http://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/5152. [ Links ]

Maguire, R. 2005. Lessons learned from implementing an electronic records management system. Records Management Manual, 15(3): 150-157. [ Links ]

Mazman, G. S., Usluel, Y.K. and Cevik, V. 2009. Social influence in the adoption process and usage of innovation: gender differences. International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 3(1): 31 -34. [Online]. http://waset.org/publications/11887/social-influence-in-the-adoption-process-and-usage-of-innovation-gender-differences (6 February 2018). [ Links ]

Mosweu, O. 2016. Critical success factors in electronic document and records management systems implementation at the Ministry of Trade and Industry in Botswana. ESARBICA Journal, 35: 1-13. [ Links ]

Mosweu, O., Bwalya, K and Mutshewa, A. 2016. Examining factors affecting the adoption and usage of Document Workflow Management System (DWMS) using the UTAUT model. Records Management Journal, 26(1): 38-67. [ Links ]

Mosweu, T.L. 2012. An assessment of the Court Records Management System in the delivery of justice at the Gaborone Magisterial District. MA thesis. University of Botswana. [ Links ]

Mugambe, P. 2017. UTAUT model in explaining the adoption of mobile money usage by SMEs' customers in Uganda. Advances in Economics and Business, 5(3): 129-136. [ Links ]

Munetsi, N. 2011. Investigation into the state of digital records management in the provincial government of Eastern Cape: a case study of the Office of the Premier. Master's thesis. University of Fort Hare. [Online]. http://ufh.netd.ac.za/bitstream/10353/496/1/Munetsithesis.pdf (20 January 2018). [ Links ]

Murgor, T.K. 2015. Challenges facing adoption of information communication technology in African universities. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(25): 62-68. [ Links ]

Mutimba, C.J. 2014. Implementation of electronic document and records management system in the public sector: a case study of the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology. Master's thesis. University of Nairobi. [Online]. http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/76120/Mutimba_Implementa tion%20of% 20electronic%20document%20and%20records%20management%20system.pdf?sequence=3 (26 July 2018). [ Links ]

National Archives of Australia. 2011. Implementing an EDRMS: information for senior management. Commonwealth ofAustralia: Canberra. [Online]. http://www.naa.gov.au/Images/EDRMS-senior-management-publication_tcm16-88769.pdf (1January 2018).

National Archives of Australia. 2011. Implementing an EDRMS: key considerations. Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra. [Online]. http://www.naa.go v.au/Images/EDRMS-key-considerations_tcm16-88772.pdf (12 November 2018).

Ojo, R.R. and Grand, B. 2011. An analysis of the extent of IT acceptance and use for knowledge management in Botswana law organizations. Infotrends: An International Journal of Information & Knowledge Management, 1: 27-37. [ Links ]

Orlikowski, W.J. 2000. Using technology and constituting structures. Organization Science, 11(4): 404-428. [ Links ]

Queensland State Archives. 2010. Guideline for the planning of an electronic Document and Records Management System (eDRMS). [Online]. https://www.scribd.com/document/73318899/eDRMS (10 December 2018).

Radu, L.D. 2016. Determinants of green ICT adoption in organizations: a theoretical perspective. Sustainability, 8: 1-16. [ Links ]

Rogers, E.M. 1995. Diffusion of Innovation. 4th ed. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Rogers, E.M. 2003. Diffusion of Innovation. 5th ed. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Seymour, L., Makanya, W. and Berrange, S. 2007. End users' acceptance of enterprise resource planning systems: an investigation of antecedents. Proceedings of the 6th annual ISOnEworld conference. 11-13 April 2007. Las Vegas, NV: Information Institute. [ Links ]

Singh, I. and Punia, D.K. 2011. Employees' adoption of e-procurement system: an empirical study. International Journal of Managing Information Technology (IJMiT), 3(4): 85-95. [ Links ]

Sykes, T.A., Venkatesh, V. and Gosain, S. 2009. Model of acceptance with peer support: a social network perspective to understand employees' system use. MIS Quarterly, 33(2): 371 -393. [ Links ]

Taiwo, A.A. and Downe, A.G. 2013. The theory of user acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): a meta-analytic review of empirical findings. Journal of Theoretical & Applied Information Technology, 49(1): 48-58. [ Links ]

Taylor, S. and Todd, P. 1995. Understanding information technology: a test of competing models. Information Systems Research, 6(2): 144-176. [ Links ]

Totolo, A. 2007. Information technology adoption by principals in Botswana secondary schools. Doctoral thesis. Florida State University. [Online]. http://etd.lib.fsu.edu/theses/available/etd-07032007182055/unrestricted/AngelinaTotoloDissertation.pdf (19 January 2018). [ Links ]

Venkatesh, V., Morris., M.G., Davis, G.B. and Davis, F.D. 2003. User acceptance of Information Technology: toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3): 425-478. [ Links ]

Voutinioti, A. 2013. Determinants of user adoption of e-government services in Greece and the role of citizen service centres. Procedia Technology. 9: 238-244. DOI:10.1016/j.protcy.2013.11.033. [ Links ]

Wilkins, L., Swatman, P.M.C. and Holt, D. 2009. Achieved and tangible benefits: lessons learned from a landmark EDRMS implementation. Record Management Journal, 1(91): 37-53. [ Links ]

Yi, M.Y., Jackson, J.D., Park, J.S. and J.C. Probst, J.C. 2006. Understanding information technology acceptance by individual professionals: toward an integrative view. Information & Management, 43(3): 350-363. [ Links ]

Yin, B. 2014. An analysis of benefits and issues in EDRMS implementation: a case study in a New Zealand organisation. Master's thesis. Victoria University of Wellington. [Online]. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10063/3723/thesis.pdf?sequence=2 (13 November 2017). [ Links ]

Yount, R. 2006. Research Design and Statistical Analysis for Christian Ministry. 4th ed. Fort Worth, Tex.: W.R. Yount. [ Links ]

Yusof, Y.M. and Ramayah, T. 2011. Factors Influencing attitudes towards using electronic HRM. 2nd International Conference on Business and Economic Research Proceeding. 14-15 March 2011. Langkawi, Kedah, Malaysia: ICBER. [Online]. http://www.internationalconference.com.my/proceeding/2ndicber2011_ proceeding/2742nd%20ICBER%202011%20PG%201510-1520%20Electronic%20HRM.pdf (6 February 2018). [ Links ]

Zaied, A.N.H. 2012. Barriers to e-commerce adoption in Egyptian SMEs. Information Engineering and Electronic Business, 3: 9-18. [ Links ]

Zeal, J, Smith, S.P. and Scheepers, R. 2010. Conceptualizing social influence in the ubiquitous computing era: technology adoption and use in multiple use contexts. Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems. 12-15 December 2010. Saint Louis, Missouri, USA: ICIS. [ Links ]

Received: 10 April 2018

Accepted: 30 November 2018