Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science

On-line version ISSN 2304-8263

Print version ISSN 0256-8861

SAJLIS vol.84 n.2 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7553/84-2-1761

RESEARCH ARTICLES

From planning to practice: An action plan for the implementation of research data management services in resource-constrained institutions

Louise PattertonI; Theo J.D. BothmaII; Martie J. van DeventerIII

IProfessional librarian with shared responsibility for repositories at the CSIR, and a Master's graduate (M.IS) of the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa. lpatterton@csir.co.za ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8067-8545

IIProfessor emeritus and contract professor in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa. theo.bothma@up.ac.za ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7850-3263

IIIResearch associate in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa. vandeventer.martie@gmail.com ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9776-1177

ABSTRACT

Research data management (RDM) and its accompanying services and infrastructures are predominantly still in a state of infancy in many African countries and little is known about the RDM habits of the researchers from these areas. Our research showed that researcher RDM behaviour is similar across the globe, but our experience was that the will to implement formal RDM is not. Similarly, the responsibility for RDM implementation is not always clear. What is clear is that, although the library should not assume primary responsibility, it does have a role to play in the successful implementation of RDM services. This paper briefly discusses the results of two RDM surveys conducted at a relatively resource-constrained, albeit leading, South African research institute. The surveys were designed to establish the RDM habits as well as the RDM needs as expressed by both emerging and experienced researchers at the stated institute. The intention was to use the results to initiate full-scale implementation of RDM services by the library. It was interesting to note that neither the emerging nor the experienced researchers showed significant deviations in research behaviour compared to that found amongst their colleagues in more well-resourced environments. What was different is that implementation grinded to a halt and that an action plan that deviated from that in published literature had to be developed so that relevant progress could still be made. This RDM action plan includes a range of stakeholders and would be of use to research institutes starting out on the RDM journey.

Keywords: Research data management, resource-constrained institutions, RDM implementation, RDM action plan

1 Introduction

Providing proof of research data management (RDM) when applying for research grants is a relatively new requirement for research funding in South Africa. A good example of this development is the decision taken by the National Research Foundation (a main contributor to publicly-funded research in South Africa) that recipients of National Research Foundation (NRF) grants would need to indicate how the data generated by the research will be made publicly accessible. In addition, the NRF requires data supporting publications resulting from funding to be deposited in an "accredited Open Access repository" and for a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) for future citation and referencing to be provided (National Research Foundation 2015). While the NRF's statement is a promising step and indicative of a national entity realising the importance of RDM, South Africa is still lagging behind the likes of the United States of America (USA) and the United Kingdom (UK) in this regard, where major funders insist on data management plan (DMP) submissions, provide detailed guidelines on DMP completion, and have in place RDM policies. Examples of eminent UK funders which have data policies and stipulated requirements around DMPs in place include the Medical Research Council (2017), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (2017) and the Economic and Social Research Council (2017). In the USA, the National Science Foundation (2017) has required completed DMPs since 2011, and their current webpage supplies links to additional requirements and plans as specified by respective directorates, offices and divisions.

1.1 RDM in South Africa

Having to adhere to funder requirements may be seen as a catalyst for organisations to establish RDM services and infrastructure and to appoint designated RDM personnel. However, despite the NRF's stated data requirement, formalised RDM and institutional RDM support at many South African research institutes is currently still at an early stage. Terms describing this state of affairs, such as "haphazard" (Kahn et al. 2014) or "slow" (Van Deventer & Pienaar 2015), feature strongly in South African RDM discussions. Even though articles and reports are being published on the topic, the exploratory nature of the current South African RDM community is evident. Apart from a decade-long data curation service existing at the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) - a frontrunner in the local data management scene (Lõtter & van Zyl 2015) - most institutes are not yet at a stage where infrastructure, services and staff form part of an established institutional RDM regime. As a result, current RDM-related literature tends to report on investigative surveys that have been conducted, pilot projects that have taken place, or tools and software that are being tested. Examples of this trend include reports of RDM surveys at the University of Pretoria and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) (Van Deventer & Pienaar 2015), pilot projects at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (Chiware & Mathe 2015) and the six-month long nationwide digital repository testing of Figshare and Islandora , spearheaded by the Data Intensive Research Initiative of South Africa (DIRISA 2018). An encouraging activity which is indicative of national RDM interest and progress is the establishment of the Network of Data and Information Curation Communities (NeDICC), a South African RDM community of practice, and its short, yet productive, contributions in terms of RDM-centred workshops and meetings (NeDICC 2017).

While published studies reveal that South African RDM is in its early days, there are many RDM-related internal reports or departmental assessments, but these have been found to be sensitive or confidential in nature, leading to them remaining unpublished. Reports that are published often lack detail and might only mention a few RDM practices or requirements. The sensitive nature of results of an RDM survey at the University of Pretoria (Pienaar personal communication 2013), the confidential nature of RDM results at another South African university (Shai personal communication 2014) and the unpublished results of a HSRC RDM survey (Lõtter 2014) give credence to this point. One institute, while being recognised as a foremost Science, Engineering and Technology (SET)-based research institute on the African continent with many of its projects publicly funded, lacked, at the time of this research, formalised institutional RDM procedures and infrastructure.

1.2 Published guidance for RDM service establishment

Guidelines and implementation plans for the establishment of RDM services are indeed available, examples being the Digital Curation Centre (DCC) guidelines for higher education institutes (Jones, Pryor & Whyte 2013), the Library and Information Technology Association (LITA) guide (Krier & Strasser 2014) and a DCC guide on delivering RDM services (Pryor, Jones & Whyte 2014) - but the focus is on the developed world where sufficient funding is available for employing adequately skilled human capacity, developing infrastructure and experimenting with a variety of options when it comes to best practice and the development of standards. The DCC guide (Jones, Pryor & Whyte 2013), for example, gives detailed case studies of RDM implementation at Johns Hopkins University, USA, the University of Southampton, UK, and Monash University, Australia. Currently, there are no readily-available RDM implementation guides focusing on the plight of the under-resourced library, the financially embattled research unit, or the higher education institute faced with budget cuts and staff reductions. RDM resource constraints could be caused by unenlightened management unwilling to invest in infrastructure and other resources for RDM or could be caused by a need to address more urgent priorities. These hurdles should not prevent the library from planning to introduce new services to enable researchers to make their data accessible. As such, research centres and universities in resource-constrained institutions are in need of a relevant RDM implementation plan, guiding them towards the establishment of RDM services while taking into account their limitations and restrictions with regards to human resources, infrastructure and finances.

The library attached to the SET-based organisation which is the subject of this study attempted over a period of three years to advance RDM in the institution. After an investigation into the RDM behaviour of emerging researchers, there was a general realisation that it was not feasible to approach RDM service implementation in the same way as is described in the literature. It was found that it was not so much the researcher behaviour, but rather the approach to implementing RDM that needed to be adapted to make provision for a different set of circumstances and priorities. Recommendations reported in this study were originally formulated for a specific South African SET-based organisation, but it is anticipated that they would also be applicable to other institutions operating in similar circumstances.

1.3 Researcher behaviour as the foundation for RDM service development

The use of survey results as a guiding tool when planning RDM services is commonplace in the literature: viewing the current situation before starting on an RDM toolkit is seen as necessary (LEARN 2016), it could benchmark awareness of infrastructure (Wilson 2013), is seen as crucial in the development of RDM services (Scaramozzino, Ramirez and McGaughey 2012; Wilson 2013; Sewerin et al. 2015), and can be used to make recommendations regarding an institute's RDM (Mossink & Bijsterbosch 2013). In addition, survey results have been used to identify gaps in current services (Averkamp, Gu & Rogers 2014), recognise unmet researcher needs (Jahnke & Asher 2012) and inform the development of RDM policies and infrastructure (Kennan & Markauskaite 2015). This study followed a similar path: information about current RDM habits, needs and challenges were investigated, which led to an action plan for successful RDM implementation.

To reiterate: information about the RDM habits of South African SET-based researchers is scarce. Two surveys (Patterton 2014; Patterton 2017) entailing in-depth investigations of RDM practices exhibited by (i) experienced and (ii) emerging researchers, as well as the RDM services required by them, addressed this knowledge gap. This paper summarises the results of these RDM surveys. The value of the study's recommendations lies in the fact that it aims at involving several stakeholders. It takes into account the distinct character of less-resourced research establishments and, as such, forms an RDM action plan for those who recognise the importance of RDM but who lack the impetus and resources to get initiatives off the ground.

2 Methodology

Two separate RDM surveys were conducted in order to determine the existing RDM practices of SET staff at a large research institute. No formalised RDM services, infrastructure, personnel or procedures were in place when the first survey was conducted. Experienced researchers' RDM habits were established through personal interviews; thirty-six research group leaders formed part of this investigation (Patterton 2014). Two years later, forty-eight emerging researchers were respondents in the second survey where an online questionnaire was the information-gathering tool (Patterton 2017). Both surveys made use of total population sampling. Reponses rates were 36% and 27% of the institute's total number of research group leaders and emerging researchers respectively. The surveys were conducted two years apart and were initially not intended to form part of the same study, thus survey questions were not identical. The number of identical questions, however, still made it possible to compare RDM activities of both groups with regards to:

• data type/formats used;

• data volumes reported;

• data software applications used;

• use of DMP;

• data storage location;

• data backup practices;

• metadata creation;

• data sharing practices;

• data preservation practices; and

• RDM training received.

The survey for emerging researchers contained questions on more RDM areas than the earlier survey for experienced researchers; this fact should be kept in mind when findings in the results section refer to this group only. Survey findings were seen to provide a reliable overall picture of data management practices among the institute's experienced as well as emerging researchers. These practices not only gave an indication of the institute's RDM practices, but also highlighted the gaps and limitations in RDM services, infrastructure, policies and procedures. As such, findings provided a foundation for the recommendation of steps to be taken to advance the data management service at the institute. The surveys also surfaced the fact that researcher behaviour was similar to that reported in the literature. Due to resource constraints, however, their practices were not aligned with recommended good practice. Survey results and the implications thereof are summarised in the next section.

3 Results

Results of both the surveys are summarised in this section. Where possible, the similarities and differences between the two groups are shared.

Of the emerging researchers, 8-10% indicated that they did not have any knowledge about a formalised RDM policy, research data ethics requirements, data citation and/or standardised procedures (this question was not posed to experienced researcher). When asked about research data characteristics (entailing data types, data volume, data software), responses revealed that experienced as well as emerging researchers made use of many different data types, both groups totalling more than fifteen types. The most common data formats across both groups were spreadsheets, image files and textual data formats. A wide range of data volumes were used within the institute, with datasets ranging from less than 1GB to datasets bigger than 100TB. The total amount of data used per researcher, as opposed to the typical dataset size, showed similar differences and ranges. Across the institute, at least seventy-three different software applications were in use. Looking at these results from the organisation's point of view is important as data storage, long -term preservation as well as skills to maintain collections of data are all impacted by differences between them. Ultimately, the costs associated with 'free choice' when it comes to data formats could be considerable and cannot be accommodated when resources are constrained. The typical range of formats is visualised in Figure 1, which shows the data types used by emerging researchers.

Questions about DMPs formed part of the emerging researcher study only, with 76% indicating never to have created a DMP. The small number of experienced researchers (28%) indicating familiarity with RDM could be seen as a sign that the majority of them would also not be making use of DMPs for their research. This number is also akin to the number of emerging researchers (56%) indicating that they were unaware of funders' RDM requirements. From an organisation's point of view, these responses have training and policy implications. Researchers will in all probability not complete DMPs if there are no consequences of not doing so.

Similarities with regards to data storage habits were found: emerging as well as experienced researchers used many storage locations each, with a personal computer found to be the most commonly-used location. Both studies showed prevalence of use of the institutional shared drive, external hard drives and other portable storage devices. It is important to mention that neither study showed that researchers were using curated discipline-specific data repositories.

Although results showed that all participants backed up their data, the frequency of backups demonstrated varied practices. Emerging researchers were more likely than their experienced counterparts to run backups on an ad hoc basis. Both groups, however, placed a high premium on daily data backups. Backup strategies further indicated that emerging researcher data is most commonly backed up to an external hard drive, while the experienced group favoured an institutional computer drive or server. In addition, younger researchers were more likely to make use of cloud services than established researchers. For an institution, this behaviour points to risk that has to be mitigated.

The use of metadata as an RDM practice exhibited a troublesome trend. Forty-two percent (42%) of experienced researchers indicated that they created and added metadata, compared to only 15% of emerging researchers who said they did so. Even when metadata was added, it appeared to be ad hoc and subjective as the majority of respondents indicated that they did not make use of a specific metadata standard. Without appropriate metadata, the data is essentially not sharable.

Data sharing practices revealed similarities across the two groups: both portrayed a high willingness to share data with peers. Only a very small percentage of respondents in both groups (12% and 8% respectively) were not willing to share data at all. Data sharing methods seemed to be similar across both groups; findings showed the prevalence of emailing, FTP, cloud-based services, and portable devices across the institute. In addition, neither group appeared to be using discipline-specific data repositories as storage location. This either means that the sharing option was not being utilised by this institute's researchers or that the researchers were not aware that subject repositories exist. The majority of emerging researchers revealed that they had not received any requests for their data within the last five years. Survey results showed that data preservation activities were not being performed, archival procedures were not in place, the institute's archivist was not consulted, and the institutional archive was not being used. In addition, emerging researchers' post-publication data was most commonly simply stored on their own computers. In essence, these gaps point to the fact that a valuable organisational asset had not yet been recognised as such.

Survey results indicated that the majority of emerging researchers (88%) had never received any RDM training. RDM training per se was not a measured variable when surveying experienced researchers, but the previously-mentioned low levels of RDM awareness and insight would indicate that RDM training had in all probability not been received. Although there is no definitive proof that experienced researchers behaved similarly, the most common RDM task being performed by emerging researchers at the time of the survey was file-labelling (using standardised naming conventions), followed by storage and backup of data. Activities such as metadata preparation, adhering to a metadata standard, and keeping an inventory of data versions and/or locations of data versions, were few and far between. With a few exceptions, emerging researchers generally rated all hypothetical RDM services as either 'important' or 'very important', as shown in Figure 2 in which the results of a question asking respondents to rate the importance of several key RDM services are shown. Participants were also given the option to indicate their inability to rate a service if they were unfamiliar with it.

On the whole, and not entirely unexpected, researchers at this institute displayed RDM habits not fully aligned with best practices. While backup frequency was indicative of good data practice, findings showed shortcomings in the areas of DMP usage, training, data preservation, metadata usage and data storage locations. In the final instance, researchers were asked to express RDM concerns and needs not addressed in the survey. Emerging researchers reported four challenges. While the same challenges were reported by experienced researchers, this group also surfaced many more. The challenges recorded can be divided into the following five categories:

• Information and Communications Technology (ICT)-related: Although ICT-related challenges may be regarded as those of research infrastructure, both storage capacity and data transfer rates were deemed important by some researchers in each of the groups. Researchers felt that the available systems were not user-friendly or that they possessed serious flaws; that there were too many systems; that download, upload and internet speeds were slow; that computing power was insufficient; that shared storage was not being managed properly; and that they did not trust ICT to take care of the confidentiality and security of their data. Lack of sufficient storage space (electronic and physical) was a big challenge for many. The lack of shareable workspaces, especially when collaborating with outside parties, was another concern. Researchers also admitted to requiring access to data when off-site or in remote areas. Concerns were also aired regarding compatibility of open source software, software/media expiry and outdated technology.

• Data security issues: Researchers stated that they were concerned about possible data loss, accidental data deletion, data corruption, encryption problems and data loss due to equipment theft. The implications of not having a disaster management plan was a concern for many.

• Financial constraints: Software packages, servers and licenses were often too costly to afford and, as a result, reserachers were using out-of-date tools and equipment.

• RDM practices: Researchers experienced difficulties when deciding on naming conventions, did not have sufficient backup knowledge and had no experience in adding metadata. Concerns were also raised about the integrity of data collection methods, quality control, best RDM practices not being applied, data not being accessible when a colleague leaves, and researchers not making data available to members of the research group.

• Data sharing/data confidentiality: The unethical use of data by other parties, as well as worries about soundness of confidentiality measures taken were burdening issues. An interesting concern was that the younger generation of researchers is used to sharing all information - for them open access is the norm - and that the need to install a mindshift when they are dealing with confidential or sensitive information is proving troublesome. Managing intellectual property issues at the start of a project also seemed to be a worrying issue.

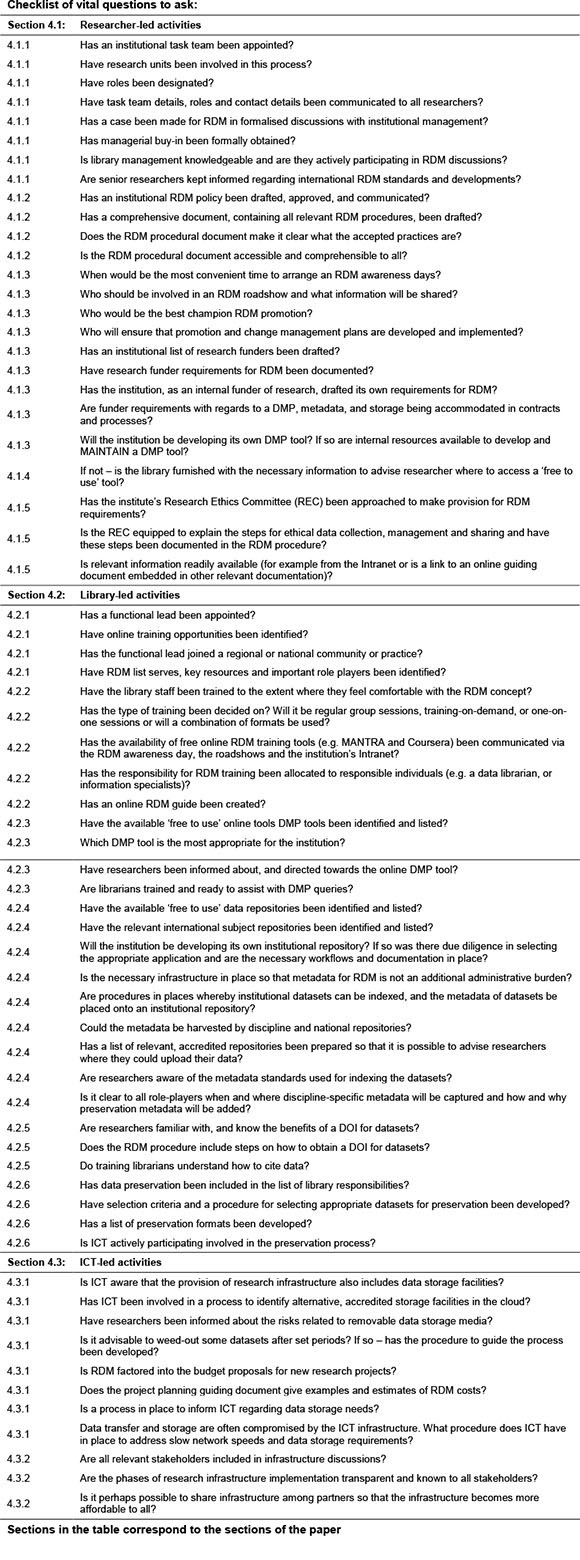

In general, the RDM habits and practices of individuals displayed some variance that ranged between rudimentary RDM practices (such as naming conventions) and advanced, well-established habits (such as consistently making use of cloud services to store well-documented data and even, in one instance, contributing data to a subject repository). This finding was expected, as the absence of formalised infrastructure and practices at institutional level meant that data management would be left up to research units, individual research groups, project leaders, or even individual researchers. Practice would need to be addressed once it is acknowledged that data are assets. Once the limitations in practice had been surfaced it was possible to develop an RDM action plan. The plan, entailing recommendations based on the survey findings, is put forward in the next section. The recommendations, read in conjunction with a set of questions (see Appendix A), provide a checklist for those wishing to implement RDM services at their organisation.

4 RDM Action plan

This section focuses on steps to be taken in order to ensure that RDM services are implemented - even at resource-constrained institutes. The steps, forming an action plan, share some similarities with current literature on the topic of data service implementation. Examples of this overlap include the popular publication by Pryor, Jones and Whyte (2014) where the inclusion of an RDM policy, DMPs and guidance/training are seen as important steps to be taken by institutions implementing RDM services, and which are steps featured strongly in the action plan below. The publication (Pryor, Jones and Whyte 2014) featured examples of RDM service implementation in Australia, the USA, and the UK indicating its general applicability. This RDM action plan acknowledges that several role players are closely involved in ensuring a successful implementation and that all activities should not be led by one department. The recommendations have therefore been subdivided into three categories representing the different stakeholders that actively need to collaborate in a successful implementation of formal RDM. Each step/activity is described and a rationale for its importance is given culminating in key questions (reflected in Appendix A) to be asked when implementing institutional RDM. A vital point is that the library should not accept leadership responsibility for all RDM-related implementation activities. It is also not possible to implement all activities simultaneously. When the workload is shared, the chances of successful implementation increase exponentially.4.1 Researcher-led activities

Researchers themselves are responsible for good research conduct. Managing research data responsibly is a component of good research. Libraries have to participate actively in and be aware of activities related to good research conduct but, in our opinion, researchers should be encouraged to set the tone and lead the charge. In the absence of a research office or an executive manager leading research, it would be necessary to influence senior research staff to manage their research data. The library's role here is therefore to influence strategic decisions. Librarians involved should be well-informed about RDM responsibilities but should not themselves be seen as the responsible party.

4.1.1 Institutional acceptance and managerial involvement

As with any other activity related to assets or matters of strategic importance, it is crucial that institutional managerial approval for and support of a focused RDM drive is obtained at the onset of any organisation-wide RDM initiative. A concerted effort, therefore, needs to be made to involve and convince principal investigators and research managers of the importance and benefits of RDM. They, in turn, should plan the envisaged steps to be followed to establish RDM at the institute. The importance of RDM has to be conveyed to those responsible for research management as well as other relevant parties involved at institutional policy level. It is best if those whose credibility as researchers are at stake take on the responsibility of convincing executive management that data are assets that need to be properly managed. The active buy-in and support of executives will, to a large extent, determine the rate of implementation success. Resources required to do so are minimal and would not require additional financial investment. Skill is required in identifying relevant information to share with executives; similarly, communications skills are necessary to convey the right message at the right time to them.

4.1.2 RDM policy and RDM procedure

Key steps in getting RDM formalised would be the creation of, firstly, an institutional RDM policy and, then, appropriate RDM procedures. The procedures, a comprehensive document stipulating the steps to be followed by researchers when managing their research data, should be inclusive, making provision for all relevant disciplinary requirements and practices. As revealed via survey findings, RDM practices as well as research data characteristics were different among the study population; as such (and to use two examples only), the concept of a 'typical data format' or a 'one-size-fits all metadata standard' would not suffice at a multi-disciplinary research institute. At the same time, though, unnecessary differences in practices and data characteristics within different research groupings have to be reduced. It is best to identify disciplinary standards, then document the selected standard, and, finally, allow the group to monitor and measure compliance to the standard. Though not essential, the library could play the role of a records manager, ensuring that procedures documentation is validated and disseminated to all staff. The procedures are essential to the development of training material - which is discussed as one of the library-led activities (4.2 below). Resources required relate to staff time. The activity of producing RDM policy and procedures should have very limited financial impact on a resource-constrained institution.

4.1.3 Promotion, awareness creation, and change management

Raising awareness about RDM and promoting good RDM practice in the institution is very important for the success of an implementation plan. Although word-of-mouth and ad hoc interventions are valuable, the importance of planned promotion and awareness campaigns should be stressed. Similarly, the value of proper change management planning should not be underestimated. Activities such as open-invitation RDM awareness days (where new trends and developments are shared) and RDM roadshows (where a series of presentations/discussions are taken to the research staff) and demonstrations of RDM tools (for example, a DMP tool) will all contribute to raising awareness across the institution. These activities do not require large resource inputs and could take place while a policy and the RDM procedures are being formulated. The library could support these activities by maintaining an up-to-date RDM blog on the institute's intranet, by regularly posting informative articles about RDM (informing researchers of training opportunities, webinars, developments and new tools related to RDM) and by equipping information specialists with the skills to assist in promoting RDM-related events. Content of the RDM blog could include explaining the need for and benefits of RDM and linking to RDM policy and procedure, an RDM glossary, an online DMP, best practice guidelines, online RDM training tools and the RDM requirements of the institute's main research funders. None of the resources required need to place a financial burden on the institution. Access to the internet is essential, but the activities recommended here are usually cost-free and require only very basic ICT skills.

4.1.4 Funder requirements

It should be anticipated that researchers could be unaware of funders' RDM requirements. Researchers may also express the need for training in understanding funder RDM requirements. Once researchers have identified relevant research funders, the library could assist by identifying funder-specific requirements and by making these publicly known. It is proposed that funder requirements be given their fair share of prominence when creating RDM best practice guidelines and training material. Funder requirements should feature on the RDM blog and, if feasible, could be embedded in an online DMP tool. This means that the online DMP tool should be customisable and able to cater for all funders of the institute's research. Developing an online DMP tool would require technical skills and an investment in technical infrastructure. However, there are several free-to-access services available online and the library could play an important advisory role in identifying such tools and in training researchers to use them effectively.

4.1.5 RDM and research ethics

With ethical clearance forming part of responsible research conduct, it is recommended that the Research Ethics Committee of the institute document and explain the steps, activities and RDM requirements needed to collect and work with data ethically. These steps need to be drafted into an ethics procedure document which could be made accessible via the institutional research ethics webpage. Resources required are, again, limited to staff time but, as ethical research is a primary concern of the Research Ethics Committee, the drafting of such a procedural document should not be arduous. The library could provide the resources to embed the procedure document and to disseminate the information through both online distribution channels as well as via training.

4.2 Library-led activities

Activities identified here speak to the core of the library's responsibility for RDM. These are the activities where the librarians involved should display operational expertise and technical know-how. These are also the activities that should not be disregarded just because a formal RDM policy is not in place.

4.2.1 Establishing an RDM function

Understanding RDM is not complex, neither is it complicated. However, the sheer volume of information as well as the interconnectedness of issues such as copyright and trusted repositories makes the task daunting. When resources are constrained, it is recommended that at least one person is relieved of other duties to focus on developing the RDM function of the library. Such a data librarian should preferably have some personal experience in working with data. A master's degree is therefore seen as a minimum requirement. This individual should be authorised to coordinate and drive the library's RDM activities. If the library does not have suitably qualified staff, it may be necessary to second a staff member from the research community to coordinate the activities. Formal RDM training is currently rare in the library community and therefore the individual would need to be a self-starter with lifelong learning skills. It is recommended that the appointed librarian actively investigate and pursue online training opportunities, including courses, workshops, unconferences and webinars. Fortunately, there is a wealth of information, including open access course material and a very active community, to provide the individual with guidance and support via the internet. Personality traits of this individual, rather than additional resources, would determine success. Depending on background and personal qualities, this librarian would need three to six months to become comfortable with the RDM subject matter. The next phase would then require that the individual capacitates other library staff to assist with the operational activities around RDM.

4.2.2 RDM training and guidance

Lack of RDM training was a reality experienced by the majority of the emerging researchers of the institute under investigation. It can be safely assumed that many universities are not yet ready to provide graduates with the necessary training to manage their own data. Furthermore, emerging researchers indicated an interest in receiving training in many RDM activities. Based on these results, it is recommended that RDM online training materials be developed, embedded in online resources and promoted to the researcher community. It is not essential that training material be developed from scratch: external online training tools are available and widely used. One recommended example of such training is MANTRA, the RDM tool developed by the University of Edinburgh (EDiNA 2018). If institutional guideline documents are used for training purposes, these should be updated to include RDM requirements. The updated guides should be made available electronically and be marketed during the institute's on-boarding sessions for new employees - if these take place; if not, it is recommended that a process is put in place to identify new recruits so that they can be targeted for training and assistance. It is recommended that the data librarian recruits information specialists (frontline staff) to assist with the training of research staff. RDM training could be seen as an extension of information literacy programmes. Additional support would be vital should the data librarian not be in possession of a SET-based qualification, or not be familiar with discipline-specific research data formats, software, and metadata standards. It is envisaged that after a training period, information specialists responsible for providing subject-specific leading-edge information services to unit researchers would be able to provide unit researchers with RDM assistance. Assistance would involve helping with DMP completion, with submitting metadata required for dataset indexing and with DOI assignment requests, and answering basic questions around RDM activities. It is important that indexers/cataloguers also receive RDM training as dealing with data indexing-related queries would form part of their duties.

4.2.3 Providing access to an online DMP tool

Study findings revealed that DMPs are uncommon, non-mandatory and subject to arbitrariness. With funders internationally requesting proof of intended data management at the time of submission of funding proposals, it is vital that attention is paid to DMPs in the institute. In the absence of a DMP tool, researchers spend many valuable hours 'recreating the wheel' in isolation. During the strategic sessions described in section 1.2, it was recommended that it was the library's duty to make sure that researchers recognise that the creation of a DMP is part of the research process and that the use of a relevant tool creates efficiencies in the process. It is proposed that, when a project proposal is submitted to funders, the inclusion of a DMP be seen as mandatory practice. At an operational level, library staff should be able to assist researchers in understanding the requirements of a DMP. They should also be able to advise on available free tools (for example, DMPonline) that assist the researcher in preparing the DMP. It is our opinion that it is not advisable that the organisation attempts to develop a DMP tool of its own. When resources are limited, and even when it does become necessary to develop funder-specific DMP templates, it would still be better to buy into existing services. It is important that the suggested DMP tool is user-friendly and that a completed DMP is limited to a maximum length of two to three pages (on average). An intricate DMP or one that is long, cumbersome and time-consuming to execute will not ultimately be used.

Additional suggestions around DMPS include the submission of completed plans to the relevant infrastructure and support service providers. The Research Ethics Committee, the library's indexing staff, and staff responsible for data storage (primarily volume-related) could benefit from knowing about the project requirements before the project is initiated. Lastly, it is proposed that awareness creation and training form part of a DMP tool implementation too. Unless the institution wishes to own its own infrastructure, the resources required for this activity are few.

4.2.4 Providing access to online storage and dataset indexing

Where an institutional repository is already available for research outputs such as articles, conference papers, reports, theses and dissertations, it is possible to index long tail data as part of this collection. Should criteria pertaining to confidentiality, sensitivity and dataset size be met, the dataset itself could be uploaded directly into the institutional repository. One constraint of this option is that the embedded metadata standard, usually Dublin Core, would be used when the dataset is indexed. In the absence of an institutional repository, the library has two choices: either develop a dataset repository or ensure that it is able to advise individual researchers where they would be able to upload their datasets and be provided with DOIs. Here a resource such as the Registry of Research Data Repositories (Re3Data.org) is invaluable to identify relevant subject repositories. Even generic repositories such as Figshare or Zenodo could be considered. As a minimum requirement, a list of accredited and suitable digital data repositories should be drafted and made available to research staff. It should be noted that the organisational asset would not be managed when this route is followed, but the researcher would be assisted in locating a suitable data repository. Managing expectations is an important aspect to consider. Dataset indexing should initially be targeting only to those datasets that are current and ready to be shared. Retrospective indexing should only be considered when the datasets identified are of national significance or when they can provide an important addition to larger international projects. This is especially important when researchers need datasets to be digitised and they do not have the funding to recruit their own digitisation experts. Digitising data is labour intensive and not comparable to digitising documents. Here, the level of activity will determine the resources required.

4.2.5 Data citation standards

Researchers are more easily persuaded to add their data to a repository when they know the data would be cited - just as their articles are. A first recommendation here is therefore for librarians to create awareness regarding data citation and the ability to publish data papers. Researchers would need to be taught- as part of the training activity - how to cite data when datasets are acquired for secondary use. Furthermore, a persistent identifier should be regarded as a prerequisite for data citation. Very often, a DOI is assigned when data is uploaded to a repository. DOIs are issued by authorised agencies or institutions to datasets that are well described and managed (by the repository) for long-term access. Assigning a DOI to a dataset therefore allows the researcher to assume that the dataset will be well managed and accessible for long-term use. The handles used in many institutional repositories are also acceptable to use as persistent identifiers. Acquiring persistent identifiers does have resource implications, but they are less expensive than what might be expected.

4.2.6 RDM preservation services

Preservation-related findings of the study showed that data are being stored in various locations, many software applications are being used to create or access data, curated digital data repositories are not being used, and data preservation activities are not being performed. As long-term preservation of assets is a library duty, the library should be familiar with preservation standards for various formats and researchers should be encouraged to ensure that their datasets and data collections could be written to one of the accepted archival/preservation standard outputs.

4.3 ICT/Infrastructure-led activities

It is essential that the library works closely with ICT when it comes to preservation services as ICT would need to assist in identifying appropriate standard preservation formats and in automating the process to update files and to check for file corruption and technology obsolescence. A further hugely important ICT-led activity is data storage.

4.3.1 Research data storage

It was established in this study that researchers make use of a variety of unreliable media when there is no default storage provision. This data storage behaviour cannot be ignored. As such, it is recommended that a procedure for data storage is developed. The procedure should make it clear what the risks associated with removable data storage media are. Researchers should be provided with a more stable and reliable solution as to where data could be stored; obviously this requirement could be very expensive. Managing research data could have many hidden costs. The majority of these relate to ICT. It is essential that ICT surface such costs and that researchers are made aware that such costs should be factored into research proposals.

4.3.2 Research infrastructure

As was seen from the findings reported in section 3 (Results), many researcher frustrations around RDM could be linked to research infrastructure. Research infrastructure is expensive to establish and resource-intensive to maintain. What is important for the library to note is that it should be included in infrastructure discussions and that it should raise awareness regarding its own requirements when it comes to RDM services from the library.

5 Conclusion

Each organisation is unique and should have an individualised approach when taking action but the RDM action plan presented above captures the essence of RDM service implementation and should be seen as the minimum steps for the successful initiation of RDM services. The steps included in the action plan are not only large in number, but include a range of institutional services, role players and stakeholders. It is crucial to identify all the RDM role players and stakeholders and to ensure that the responsibilities for RDM implementation are fairly distributed. All internal stakeholders have to be informed of their designated roles and responsibilities. The importance to all stakeholders mentioned in the action plan of training, guidance, awareness creation and support cannot be overestimated. In conclusion, it can be stated that, while the South African RDM scene is still in its infancy, encouraging progress, in the form of nationwide projects, institutional initiatives and training efforts are surfacing. Notwithstanding these positive steps, many institutes are still dealing with less-than-ideal RDM practices and are struggling to implement formalised RDM. This study, revealing the RDM activities of established as well as emerging researchers at a resource-constrained institute, and which puts forward a list of recommendations to guide towards establishing institutional RDM, aspires to guide less-fortunate research organisations towards effectuating such activities and services.

Future research could elucidate how the practical application of the proposed actions has transpired at other institutes. Comparing challenges of the RDM experiences at this research institute, along with additional suggestions and lessons learnt, to institutes elsewhere could also form part of future research. It is anticipated that the actual implementation of recommendations at research organisations would bring to the fore additional steps required when starting out with an institutional RDM agenda. It is at that stage that we would recommend that more detailed action plans - such as that provided by the DCC guide for development of RDM services at a higher education institute (Jones, Pryor & Whyte 2013) - be utilised for a more comprehensive set of actions to be taken.

References

Averkamp, S., Gu, X. and Rogers, B. 2014. Data management at the University of Iowa: a university libraries report on campus research data needs. University of Iowa Staff Publications. [Online]. http://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1246&context=lib_pubs (14 November 2018).

Chiware, E. and Mathe, Z. 2015. Academic libraries' role in research data management services: a South African perspective. South African Journal of Library & Information Science, 81(2): 1-10. DOI:10.7553/81-2-1563. [ Links ]

DIRISA. 2018. DIRISA Services. [Online]. https://www.dirisa.ac.za/ (14 November 2018).

Economic and Social Research Council. 2017. Data management plan: guidance for peer reviewers. [Online]. http://www.esrc.ac.uk/files/about-us/policies-and-standards/data-management-plan-guidance-for-per-reviewers/ (14 November 2018).

EDiNA. 2018. MANTRA: Research data management training. [Online]. http://datalib.edina.ac.uk/mantra/ (14 November 2018).

Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. 2017. EPSRC policy framework on research data. [Online]. https://www.epsrc.ac.uk/newsevents/news/researchdata/ (14 November 2018).

Jahnke, L.M. and Asher, A. 2012. The problem of data: data management and curation practices among university researchers. Council on Library and Information Resources Reports, 154. [Online]. http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub154/problem-of-data (14 November 2018). [ Links ]

Jones, S., Pryor, G. and Whyte, A. 2013. How to develop research data management services - a guide for HEIs. DCC How-to Guides. Edinburgh: Digital Curation Centre. [Online]. http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/how-guides/how-develop-rdm-services (14 November 2018). [ Links ]

Kahn, M., Higgs, R., Davidson, J. and Jones, S. 2014. Research data management in South Africa: how we shape up. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 45(4): 296-308. DOI:10.1080/00048623.2014.951910. [ Links ]

Kennan, M.A. and Markauskaite, L. 2015. Research data management practices: a snapshot in time. International Journal of Digital Curation, 10(2): 69-95. DOI:10.2218/ijdc.v10i2.329. [ Links ]

Krier, L. and Strasser, C.A. 2014. Data management for libraries: a LITA guide. Chicago: ALA Tech Source. [ Links ]

LEARN. 2016. Is your institution ready for managing research data? [Online]. http://learn-rdm.eu/en/survey-rdm-readiness/ (14 November 2018).

Lõtter, L. 2014.HSRC Research Data Management. (Unpublished).

Lõtter, L. and van Zyl, C. 2015. A reflection on a data curation journey. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 10(3): 338-343. DOI:10.1177/1556264615592846. [ Links ]

Medical Research Council. 2017. Data sharing. [Online]. https://www.mrc.ac.uk/research/policies-and-guidance-for- researchers/data-sharing/_(14 November 2018).

Mossink, W. and Bijsterbosch, M. 2013. European landscape study of research data management. Utrecht: SURF Foundation. [Online]. http://www.clarin.nl/sites/default/files/SIM4RDM%20landscape%20report_1.pdf (14 November 2018). [ Links ]

National Research Foundation. 2015. Statement on open access to research publications from the National Research Foundation (NRF)-funded research. [Online]. https://www.nrf.ac.za/media-room/news/statement-open-access- research-publications-national-research-foundation-nrf-funded (14 November 2018).

National Science Foundation. 2017. Dissemination and sharing of research results. [Online]. https://www.nsf.gov/bfa/dias/policy/dmp.jsp (14 November 2018).

NeDICC. 2018. NeDICC: Network of Data & Information Curation Communities. [Online]. https://nedicc.com/ (14 November 2018).

Patterton, L.H. 2014. Research data management at the CSIR: an exploratory survey. (Unpublished).

Patterton, L.H. 2017. Research data management practices of emerging researchers at a South African research council. Master's thesis. University of Pretoria. [Online]. https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/59502. [ Links ]

Pryor, G., Jones, S. and Whyte, A. 2014. Delivering research data management services: fundamental of good practice. London: Facet. [ Links ]

Scaramozzino, J.M., Ramirez, M.L. and McGaughey, K.J. 2012. A study of faculty data curation behaviors and attitudes at a teaching-centered university. College & Research Libraries, 73(4): 349-365. [Online]. https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/16241/17687 (14 November 2018). [ Links ]

Sewerin, C., Dearborn, D., Henshilwood, A., Spence, M. and Zahradnik, T. 2015. Research data management faculty practices: a Canadian perspective. Paper presented at IATUL 2015. 5 - 9 July. Hannover, Germany [Online]. http://hdl.handle.net/1807/69145.

Van Deventer, M. and Pienaar, H. 2015. Research Data Management in a developing country: a personal journey. International Journal of Data Curation, 10(2): 33-47. DOI:10.2218/ijdc.v10i2.380. [ Links ]

Wilson, J. 2013. University of Oxford research data management survey 2012: the results. University of Oxford blogs. 3 January. [Online]. https://blogs.it.ox.ac.uk/damaro/2013/01/03/university-of-oxford-research-data-management-survey-2012-the-results/ (14 November 2018).

Received: 28 May 2018

Accepted: 30 November 2018