Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

De Jure Law Journal

On-line version ISSN 2225-7160

Print version ISSN 1466-3597

De Jure (Pretoria) vol.49 n.1 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2225-7160/2016/v49n1a1

ARTIKELS ARTICLES

Designing an appropriate and assessable curriculum for clinical legal education

Die ontwerp van 'n toepaslike en asseseerbare leerplan vir Kliniese Regsopleiding

M A (Riëtte) Du Plessis

LLM PhD; Associate Professor, School of Law, University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg

OPSOMMING

Die Wetsgenootskap van Suid-Afrika en die professie het aangetoon dat graduandi van die vier-jaar LLB nie behoorlik toegerus word om die praktyk te betree nie. Studente se blootstelling aan en voorbereiding vir die praktyk geskied hoofsaaklik tydens hul kursus in Kliniese Regsopleiding. Dit is dus belangrik dat sodanige kursus oor 'n toepaslike en asseseerbare leerplan beskik. Met die opstel van die leerplan moet daar gelet word op die missie en die fokus van die regskliniek, die rol van die kliniese toesighouer, asook die doelstellings, vaardighede en waardes wat nagestreef behoort te word ten einde die beoogde uitkomste te bereik. Hierdie word bespreek deur na die huidige Suid-Afrikaanse literatuur asook die leerplanne van vier Suid-Afrikaanse universiteitsregsklinieke te kyk. Internasionale tendense word bespreek en met dié van Suid-Afrika vergelyk. Tekortkominge word uitgelig en aangespreek. Die gevolg-trekkings word dan gebruik om 'n voorgestelde leerplan vir Suid-Afrikaanse universiteitsregsklinieke te ontwerp.

1 Introduction

Introduced in 1997, the four-year undergraduate LLB degree led to complaints by law firms about the level of preparation of the LLB graduates they recruit.1 The CEO of the Law Society of South Africa also indicated that most students did not have the requisite academic literacy or numeracy skills to complete the undergraduate LLB degree in four-years.2

On 16 April 2014, the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits)3announced, following extensive discussions with members of the profession,4 that the Bar, academic colleagues, and after confirmation at the Society of Law Teachers of Southern Africa Conference,5 the Wits School of Law has decided to discontinue the undergraduate four-year LLB at the end of 2014.6 From 2015, all students with an interest in law will have to enroll in the postgraduate LLB program which may take an additional two-years for those who have completed the BA Law or BCom Law.7 The Head of the Wits School of Law indicated that:

the rationale for this strategy is that a prior degree would already have prepared a prospective law student on the expectations of university education with some level of literacy, numeracy and exposure to the wider issues in South Africa and beyond that are material in their understanding of law.8

The decision was criticised by the South African Black Lawyers Association, commenting that Wits was 'pre-empting a multi-stakeholder review process' led by the Council on Higher Education.9 However, academics indicated that these review discussions had not progressed in five years. The decision was welcomed by academics at four law schools across the country, one commenting anonymously that 'it was a move that other universities should follow as the current system produced "legal barbarians" who, while trained in law, were ill-equipped to translate that into understanding how lawyers functioned in relation to society and the "power dynamics" that existed'.10

To date, no other law school in South Africa discontinued the four-year undergraduate LLB. Clinical legal education (CLE) is a mode of instruction in various law school courses - particularly courses that are described as 'clinical', such as simulation-based courses (students assume professional roles in hypothetical situations), in-house clinics (students represent clients or perform other professional roles under supervision of a member of the faculty, who is an attorney), and externships (students represent clients or perform other professional roles under supervision of an attorney who is not a member of the faculty).11 As in many global jurisdictions, CLE forms part of the LLB curriculum at most of the South African Universities.12

Given the complaints by law firms about the level of preparation of the LLB graduates they recruit,13 combined with the Law Society of South Africa's indication,14 the importance of CLE becomes more accentuated. The CLE curriculum, therefore, is of cardinal importance. CLE can encompass a variety of courses and clinical methods. CLE serves a twofold purpose, namely practical legal training of students and providing free legal services to the (indigent) community.15 Due to the students' limited practical exposure during the four-year LLB studies, the CLE curriculum became pivotal and will be discussed with reference to foreign jurisdictions.

What follows will be a curriculum review of CLE - which will include determining the mission of the clinic, its focus and the role of the clinician. It will be indicated that the pedagogy of CLE should ideally consist of three basic components, namely the clinical experience, classroom teaching and tutorial components. Outcomes, skills and values are foundational to the design of a CLE curriculum and these will be probed. In an attempt to find a comprehensive and appropriate curriculum for CLE, suggestions from foreign jurisdictions will be explored. This will be followed by a review of the curricula of four South African university law clinics.

2 CLE Curriculum Review

A recent PhD study reviewed the CLE curricula of four South African universities, namely the Universities of the Witwatersrand, Pretoria, Johannesburg and the Free State.16 These will be discussed, followed by a curriculum summary. Outcomes and skills stated for South Africa will be measured against those stated for multiple jurisdictions. The curriculum requirements identified across a number of foreign jurisdictions and the curricula of the four South African universities under review will be also compared.

In an attempt to formulate an ideal CLE curriculum, with a focus on applicability in South African university law clinics, the curriculum requirements that were identified across the foreign jurisdictions will be compared to those used by the four South African universities that were under review.17 Once the common, and ideal, components for the curriculum are identified, these will be measured against outcomes and skills determined for these components in the South African landscape. The required components for a curriculum in CLE will be identified -which clinicians may structure according to their needs, but it will be suggested that all components should form part of the teaching of CLE. As the components will be determined across a number of jurisdictions, the final suggestions may be applicable not only to South African university law clinics, but to many other jurisdictions as well.

2 1 Determining the Mission of the Clinic, its Focus, the CLE Programs and the Role of the Clinician

In order to design clinical programmes, it is imperative that the clinic has a clear mission. Once the clinic's mission is determined, it will be the foundation from which the subsequent student and institutional outcomes, curriculum, teaching methods and assessment will be reflected.18

The mission of the clinic will inform the focus of the clinic, its CLE programme and the roles of its clinicians.

The focus of a university law clinic is important in determining how the teaching methodology of CLE will be applied in the training of the students and the setting of the curriculum. This, in turn, will determine the roles of the clinicians.19

3 Pedagogy: The Clinical Experience and Inclusion of Classroom and Tutorial Components

The pedagogy of CLE should ideally consist of three basic components, namely clinical duty, classroom teaching and clinician/student tutorial sessions.20

3 1 The Clinic Experience

The infrastructure for an in-house live-client model is well established in South Africa.21 This model is used by the four South African universities reviewed. In-house live-client courses can be used to achieve clearly articulated educational goals. It is important to have a clear understanding about what students are required to learn, especially in light of the high cost of operating these clinics. Students, therefore, need to be taught about their relationships with the clinicians and the restrictions placed on their freedom to act as lawyers.22

Although acknowledging that a substantial part of traditional or doctrinal law teaching incorporates problem solving, practice-orientated clinical experiences teach students a different, but equally important, kind of reasoning. These are 'ends-means thinking', or problem-solving - described as 'the process by which one starts with a factual situation presenting a problem or an opportunity and figures out the ways in which the problem might be solved or the opportunity might be realised'.23 Vawda describes problem-solving as a highly interactive methodology whereby students and clinicians work together in solving clients' problems.24 He identifies a number of steps involved in the problem-solving approach, such as problem definition, option identification, decision making and implementation.25 The process involving these steps is applied in the clinical setting initially, with continuous re-enforcement during tutorial sessions.26 A live-client clinic enables students to scratch beneath the surface of the legal system and explore the hinterland of expectations, promises and goals engendered by the legal process.27

3 2 The Classroom Component

In a live-client clinic, a 'problem-first' approach is often used as pedagogy. This leads to clinicians labouring under an intrinsic belief that students will learn certain skills simply by seeing a real client with a legal problem. The assumption is then that they will develop further skills from having to find a solution to that problem 'on the run'. Evans and Hyams argue that, although there is evidence that many things are learnt in this manner, this 'osmotic' exposure model may not be the best way in which to learn lawyering skills.28 It is therefore advisable to run seminars and tutorial programmes alongside the live-client work. This will support and expand the legal skills learnt in the clinical environment. The classroom component is also essential because the clinician often has to 'teach things students should have learned before enrolling in client representation courses, such as the rules of evidence and professional conduct and basic lessons about lawyering skills'.29 The classroom component, whether in smaller groups or by means of seminars, is also regarded as important in the South African teaching of CLE.30 Classroom content can support a focus on professionalism and ethics,31 and is also essential for the teaching of certain types of work done by practitioners that may be substantial and that students are unable to be taught in a clinical setting only.32 This will require a concomitant reduction in casework load.33 Vawda suggests a classroom component of two hours per week where clinicians meet with all the students and offer instruction in the theory of clinical law, skills, ethics and values,34 as the focus of CLE is rather on training students than (uncontrolled) client services. Hyams holds that '[a]dequate time must be allowed in the formal clinical classroom curriculum and in the supervisor/student relationship to allow both formal (classroom) instruction and informal discussion to take place'.35 At its most basic, the emphasis of the clinic may need to be restructured so that the number of clients that are seen in a given week are reduced, or the seminar/classroom component of the units may have to undergo a renewal and change of focus.36 There is value in integrating practicing lawyers and judges into the classroom component as guest lecturers. They can give students a realistic view of the practice of law and bring diversity to clinical legal education.37

3 3 The Tutorial Component

Tutorial sessions are geared towards guiding students through the stages of learning.38 The proper implementation of CLE requires close and direct supervision of students, which will satisfy the goal/outcome aimed at ensuring that the student is working effectively, efficiently and ethically for the client.39 Clinicians should enforce regular tutorial meetings.40 CLE, of which tutorials form a large component, 'is an active pedagogy in which students are required to perform certain tasks and draw lessons from those experiences'.41 The learning process is enhanced through action, verbalisation of thoughts and an active engagement with ideas through consultation, discussion and feedback involving peers and clinicians.

The relationship between clinicians and their students is about managing the expectations of the students, clients and clinicians. Clinicians need to be consistent in dealing with these expectations, which become clear during tutorial sessions.

Tutorials are appropriate fora where student autonomy can be balanced with client protection.42 Under the guidance of the clinician, the student must develop a reflective and critical approach to his or her own experience without risking harm to the client. The highest quality experience comes from a clinician who can strike the appropriate balance between allowing the student the freedom to explore, whilst protecting the client from harm.43 Swanepoel et al describe the tutorial component in CLE as a forum where students are more relaxed and exert more effort into thinking than they would do when their immediate goal was just to memorise material to pass an imminent examination.44Tutorials were also identified as fora where the clinician's responsibility to provide a pedagogical basis for tackling ethical issues can manifest.45

Neglecting tutorials, where students are trained in professional practice, effectively prolongs and reinforces the habits of thinking like a student rather than as a practitioner.46

4 Specialisation

Specialised units within the larger clinical setting are becoming the norm at more South African university law clinics.47 Parameters for case specific and student learning criteria will ensure manageable caseloads.48

Similar to Stuckey, who voiced the perspective in the USA, Australians Evans, Hyams and Giddings believe that specialist clinical units may provide students with 'a richer skills set and a deeper and more comprehensive milieu in which to practice those skills' - which will benefit the law school and serves as a valuable resource for the community.49 Such specialised clinical units must conform to the pedagogical aims of the CLE program.

5 Outcomes, Skills and Values

Outcomes,50 skills and values are foundational to the design of a CLE curriculum which was identified as preconditions in designing a curriculum that can be assessed effectively.51

Outcomes were defined as 'the stated abilities, knowledge base, skills, personal attributes, and perspectives on the role of law and lawyers in society'.52 The outcomes of a clinical programme are relevant to the needs of the society, students and the profession.53 When planning a curriculum, certain outcomes are expected. In South Africa, seven main goals (outcomes), each with their own sub-goals, of CLE have been identified.54

Skills can be categorised as attitudinal skills, cognitive skills, communication skills and relational skills.55 In South Africa, skills are foundational to the setting of a curriculum and encompass a wide range.56

Chavkin identifies two values critical to the legal profession, namely the lawyer's relationship to opposing counsel, judges and court administration; and the lawyer's relationship to the profession.57

6 Curriculum

A curriculum which will serve the clinic's mission and the stated outcomes for the students must have certain characteristics which include focus, coherency and logical coordination, the provision for incremental and developmental formation of student abilities and that all the outcomes should be required for all students.58 The latter characteristic should be heeded when a clinic operates in specialised units where students may be exposed to different styles of practice and different experiences. It is important that valid assessment and continual feedback are an integral part of the curriculum.

Suggestions from foreign jurisdictions were explored in an attempt to find a comprehensive and appropriate curriculum.59 As part of the clinical curriculum, as it relates to student activity, it is recommended that students receive formative feedback on their clinical work; a minimum of two students be responsible for each client/case;60 students should be involved in group work; the knowledge, skills and expertise of students must be shared with their partner/group; the initial responsibility for the cases should be the students'; and weekly plenary lectures (either to the entire body of students in the clinical course, or to groups of students, in their specialised units).

In analysing the curriculum requirements set by the abovementioned jurisdictions, the following appeared to be common to all those jurisdictions in terms of course content. For CLE, each student should receive substantial instruction in: the substantive law necessary for effective and responsible participation in the legal profession; legal analysis and reasoning; legal research; problem-solving and oral communication; writing in a legal context; professional responsibility; social responsibility; practice management; observance of and reporting on trials (both civil and criminal); interviewing techniques; drafting of pleadings; drafting of letters and other formal documents; professional ethics; trial advocacy; negotiation techniques; and writing programmes.

7 Review of the CLE Curricula of the South African Universities of the Witwatersrand, Pretoria, Johannesburg and Free State

The aim of the review was to compare the clinical models used by the different clinics, whether the CLE course is compulsory or an elective and whether CLE is offered as a year or a semester course. The different clinical scenarios will be explained where after the contents of the different CLE curricula will be probed. The outcomes of the review may prove to be helpful to clinical directors at South African university law clinics.

All these university law clinics follow the in-house live-client model and students are required to attend weekly clinic duties, supervised by clinicians.

At the University of the Witwatersrand Law Clinic (WLC), students work in pairs and are allocated to a clinician who is responsible for managing their weekly clinic intake of cases. Students on duty, in consultation with their clinician(s) who attend the clinics, consult with the clients and identify suitable cases.61 No appointments are made for consultations, as the WLC operates on a 'walk-in' and 'first-come-first-served' basis. Each student pair has to attend weekly designated and compulsory clinic duty for two hours. Student pairs also have to attend compulsory 45-minute tutorials weekly with their supervising clinicians where the cases are discussed in depth, strategies are planned, instructions are given and student progress is monitored.

At the University of Pretoria Law Clinic (UPLC), students form small groups called firms consisting of five or six members called partners. They report to two clinicians who are not attending clinic, but are available. Student firms consult with clients, by appointment only, during their two-hour weekly clinic sessions.62 No formal tutorials are scheduled, but clinicians monitor students' activities through messages placed in 'pigeon holes' in clinicians' offices. Students may also approach clinicians for consultations.

At the University of the Free State Law Clinic (UFSLC), students are only required to do one semester of clinical sessions, which are divided into the following specialised units from which students are allowed to choose: Labour, Evictions, Civil, Family and Appeals. Students, who each have a student partner, have to attend clinical sessions once a week, totaling approximately twenty hours of contact sessions per student per year. The student consultation sessions are pre-arranged with clients. In the Appeals unit, students do not consult with clients but are taught by way of simulation. Regular tutorials are arranged with the clinicians.

At the University of Johannesburg Law Clinic (UJLC), students are only required to do one semester of clinical sessions. Students do not work in pairs or firms, but consult on their own. Clients consult by appointment only. Student assistants and secretaries pre-screen clients telephonically. Students are allocated specific days for clinic duty, which last from 08h00 until 13h00. No formal tutorials are scheduled and students consult with clinicians as needed.

In comparing the above four models, the following is evident: at WLC, UJLC and UFSLC, CLE is a compulsory course, which is recommended, whereas CLE is an elective course at UPLC. At WLC and UPLC, CLE is taught as a year course, whilst CLE are semester courses at UFSLC and UJLC. The advantage of semester courses, and of making CLE an elective course, is the reduction in student numbers in the course. However, by limiting CLE to a semester course, it is doubtful that students will reap the full benefits of the potential that a CLE course can offer. It will also be more beneficial to clients when the same student counsellors are available for a longer duration to attend to their cases.

Only WLC operates a 'walk-in' clinic. This is possible as WLC is better staffed than the other clinics. The remainder of this review will focus on the classroom components of the CLE courses.

7 1 University of the Witwatersrand

WLC teaches CLE in a full-year course to final year students. This experiential learning is taught in specialised units,63 where the clinicians specialise in different fields of law.64 The course consists of three components, namely plenary sessions, tutorials and clinic duty.65 The plenary sessions comprise of group lectures for all the students and small group sessions where students are taught in their specialised units. These lectures continue throughout the academic year and are taught weekly during a double lecture (90 minutes). Students are presented with a prescribed reading list.66

The curriculum for the classroom component of the CLE course is as follows:67 interviewing skills; file management; court report; basic drafting - letters and statements; professional negligence and insurance; legal research and problem solving; drafting court documents; attorneys' numeracy skills and costs; professional conduct and ethics; organisation of the legal profession; social justice; trial skills: analysis of pleadings and evidence, preparation for trial, a plenary session dealing with pre-trial procedures, analysis of pleadings and evidence; and trial skills: a plenary session dealing with court demeanor, opening statements and examination-in-chief, cross-examination and closing address, courtroom skills and a number of weeks conducting trial advocacy exercises. WLC operates in specialised units and each specialised unit will attend a workshop on courtroom skills through demonstrations, simulations and group exercises. In the specialised units,68 students also attend unit-based sessions where the law and procedure applicable to the various units will be discussed.

7 2 University of Pretoria

UPLC teaches CLE in the course to final year students as an elective. They use a combination of the live-client teaching model, simulations and plenary lectures.69

The curriculum for the classroom component, presented over the course of a semester, comprise of an introduction to the course and the law clinic, which includes the 'shadowing' of a candidate attorney; consultation skills; filing, firm duty, clinic manual, rules of the clinic and means test; court procedures, which include an overview of pleadings, notices, process, issuing and service aspects of substantive and procedural law and divorce litigation; a workshop on diversity issues; a workshop on negotiations; and legal writing and numeracy skills.70

7 3 University of Johannesburg

UJLC teaches CLE as a compulsory year course to final year students.71They use a combination of the live-client teaching model, simulations and plenary lectures. The curriculum for the classroom component comprises of oral and written communication; divorces; Magistrate's Court procedure; legal ethics; numeracy skills; legal costs; the legal profession; practice management; and trial advocacy.72

7 4 University of the Free State

UFSLC teaches CLE as a compulsory course to final year students.73 They use a combination of the live-client teaching model, simulations and plenary lectures.74 The curriculum for the classroom component comprise the following:75 consultation skills; file and case management; practice management; writing letters; drafting pleadings, notices and applications; and legal costs.76

In conclusion, Bloch and Noone identified three different models of practice used in CLE programmes, namely: (a) a relatively open-ended individual service model (as used by WLc);77 (b) a specialisation model addressing a particular area of law with a specifically targeted group of clients (integrated by all the university law clinics under review);78 and (c) a community model concerned with a local community and utilising a range of approaches (as employed by UFSLC).79

8 Curriculum Summary

It was indicated above that the outcomes, skills and values are foundational to the design of a CLE curriculum. Surveys across a wide selection of jurisdictions, pertaining to the skills, values and expected outcomes of the course were reviewed, where common requirements for curricula were identified, all of which can be used in the design of an effective and assessable curriculum in CLE.80

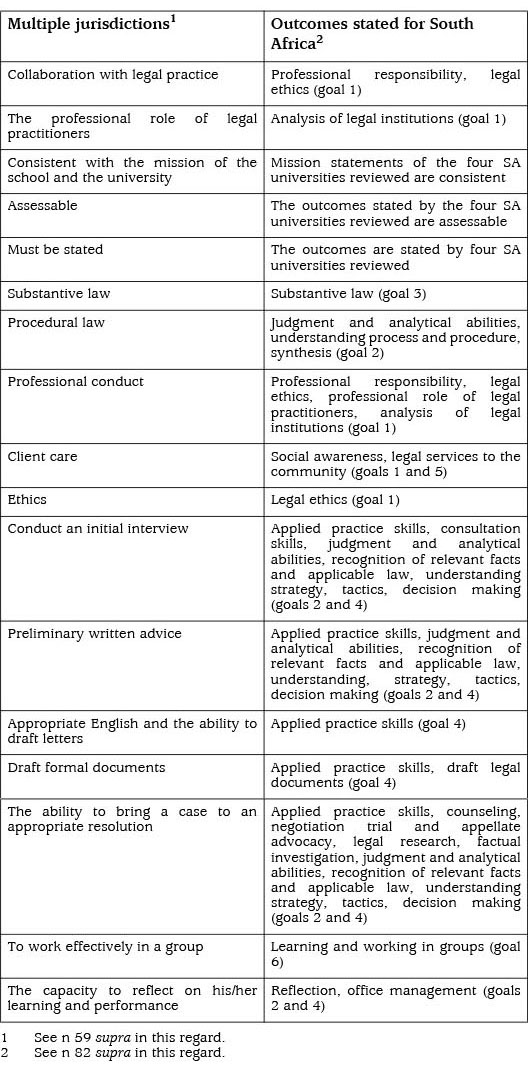

8 1 Outcomes Summary

A summary of the abovementioned jurisdictions' identified outcomes indicate that when outcomes for CLE are determined, the following should be considered: collaboration with legal practice; the outcomes must be consistent with the mission of the school and the university to ensure consistency; outcomes must be assessable; an outcome must be stated; clinics should consider how many outcomes they can reasonably address and assess during the CLE programme; the demands of the outcomes on the clinic and the students should be reasonable.81 The outcomes stated by the mentioned multiple jurisdictions, and that of the seven main goals (outcomes)82 each with their own sub-goals, identified for South Africa were compared. The results are as follows:

To consider when determining outcomes:

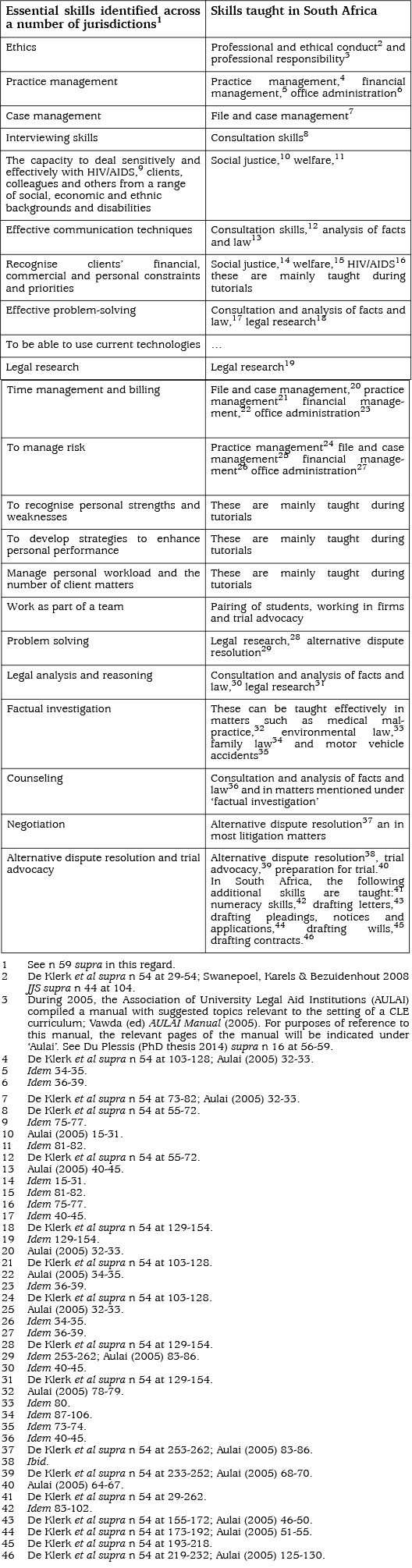

8 2 Skills Summary

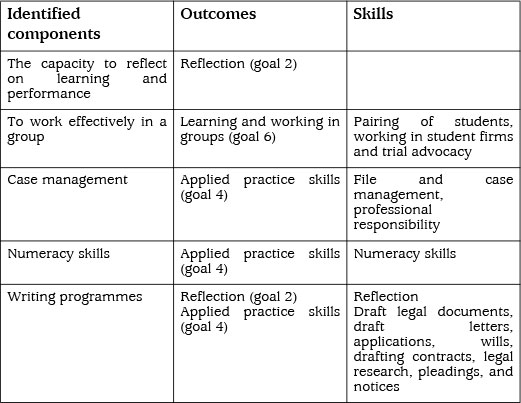

The skills identified across a number of jurisdictions and those identified for South Africa were also compared. The results are as follows:

8 3 Values Summary

The core values that were identified in foreign jurisdictions are equally important and embraced in the South African landscape and are specifically evident in the teaching and practice of ethics, professionalism and case and file management.

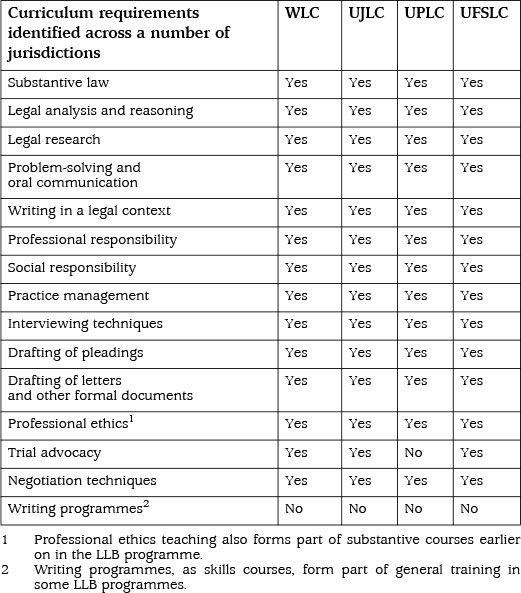

9 Curriculum Requirements Summary

The curriculum requirements identified across a number of jurisdiction and the curricula of the four South African universities reviewed in this study were also compared. The results are tabulated below:83

From the above, it is clear that the curriculum requirements identified across a number of jurisdictions and the curricula of the four South African universities reviewed compare favorably with global jurisdictions. What is apparent, however, is that the South African universities neglect the introduction of writing programmes in their CLE curricula. The importance of these programmes needs to be highlighted at Faculty and School levels to ensure urgent introduction.

10 Conclusion

Discussion on the surveys conducted by authors in the different jurisdictions indicated that CLE should be a core and mandatory course in the law degree curriculum.84 The focus of the clinic, therefore, should be on the students' academic needs and their practical training. Communities' needs for legal services are acknowledged, but such services should not be rendered at the expense of student training. Clinicians, although they generally are admitted attorneys, are academics for purposes of CLE and their main focus should be the training of the students.

In an in-house live-client clinic, students will learn certain skills through exposure but that is not enough to learn lawyering skills. It is therefore advisable to run a seminar and tutorial programme alongside the live-client work. This will support and expand the legal skills learnt in the clinical environment. Specialised units within the larger clinical setting may make more manageable caseloads possible, but students must be trained within set parameters to ensure that they are assessed in an even-handed manner across the different specialised units.

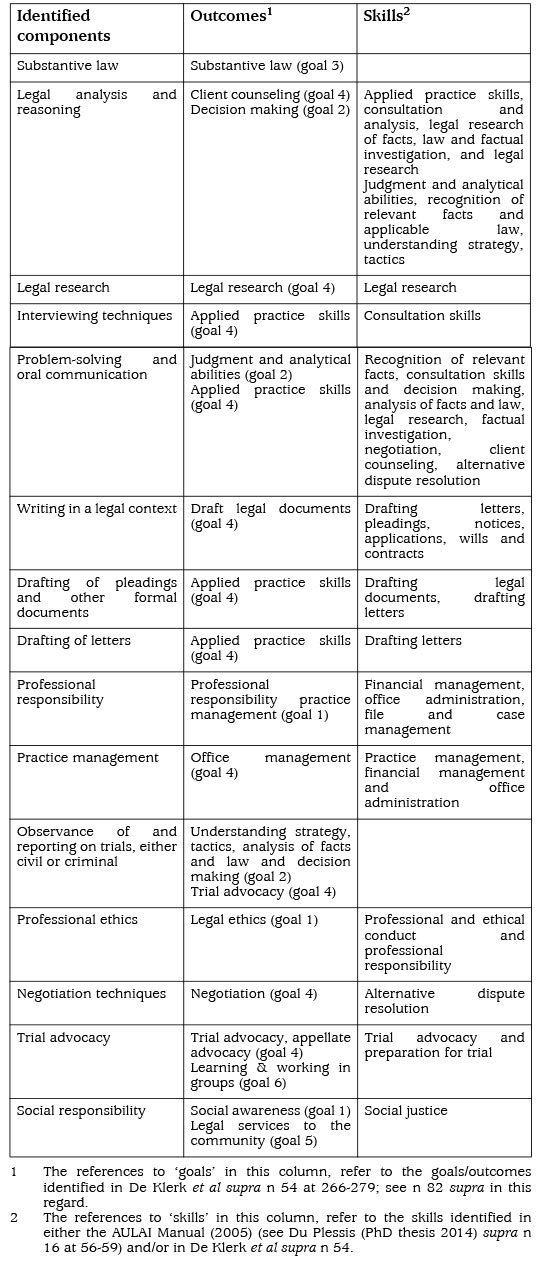

Finally, in an attempt to formulate an ideal curriculum for CLE, curriculum requirements identified across the aforementioned jurisdictions as well as those used by the four South African universities were compared.85 Once the common (ideal) components for the curriculum were identified, they were measured against the outcomes and skills determined for these components.

Additional components identified within the South African landscape:

The above identifies the required components for a curriculum in CLE. Although clinicians are free to structure the classroom component of the course according to their needs, it is suggested that the above components all form part of the teaching.

1 University World News 'Legal training uncertainty as university scraps degree' 2014 available from http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20140424114611428 (accessed 2015-04-22).

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid. Many of the discussions with law firms pointed to the lack of maturity or awareness of the graduates to be given stewardship of clients' affairs. Some firms of attorneys, who regularly recruit graduates, employ them on the proviso that they complete additional academic qualifications, such as a Bachelor of Laws or Masters degree. See http://www.wits.ac.za/law/programmes/15664/academic_programmes.html (accessed 2015-04-22); and http://www.wits.ac.za/newsroom/newsitems/201404/23367/news_item_23367.html (accessed 2015-04-22).

5 Held at the Wits School of Law in January 2014.

6 University World News 2014 supra n 1 (accessed 2015-04-22).

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Business Day Live 'Wits scraps four-year law degree to give ethical grounding' 2014 available from http://www.bdlive.co.za/national/education/2014/04/17/wits-scraps-four-year-law-degree-to-give-ethical-grounding (accessed 2015-04-22).

11 Stuckey & Others Best practices for legal education (2007) 166.

12 South African University Law Clinics Association (SAULCA) is a voluntary association of all South African University Law Clinics, established to promote and protect the interests, values and goals of its members. Part of SAULCA's mission is to promote high quality CLE programmes at universities in South Africa.

13 University World News 2014 supra n 1 (accessed 2015-04-22).

14 Ibid.

15 South African universities have identified their objectives as three-fold, namely teaching, community service and academic research. See Wimpey & Mahomed 'The practice of freedom - the South African experience' 2O06 (unpublished copy on file with author) 17. Generally, university law clinics have to satisfy two main objectives, namely teaching students and service to the community. See Du Plessis 'Closing the gap between the needs of students and the community they serve' 2008 Journal for Juridical Science (JJS) 33. [ Links ]

16 Du Plessis 'Assessment methods in clinical legal education' (PhD thesis 2014 Wits).

17 All these universities follow the in-house live-client model and students are required to attend weekly clinic duties. The formulation of a curriculum will focus on the classroom components of the CLE courses.

18 Munro 'How do we know if we are achieving our goals?: Strategies for assessing the outcome of curricular innovation' 2002 Journal of the Association of Legal Writing Directors 231-232. [ Links ]

19 Research into determining the mission of the clinic, its focus, the CLE programmes and the role of the clinician outcomes, skills and values was undertaken across several jurisdictions and is fully described in Du Plessis (PhD thesis 2014) supra n 16 at 26-36; and Du Plessis 'Clinical legal education: determining the mission and focus of a university law clinic and required outcomes, skills & values' 2015 De Jure 312-327. [ Links ]

20 See Du Plessis (PhD thesis 2014) supra n 16 at 37-41. This study surveyed multiple international and national jurisdictions and it was indicated that these three components are the ideal basis for clinical pedagogy.

21 For more on this model (also sometimes referred to as an 'in-house clinic') see Du Plessis 2008 JJS supra n 15 at 13.

22 Stuckey & Others supra n 11 at 189.

23 Findley 'Rediscovering the Lawyer School: Curriculum Reform in Wisconsin' 2006-2007 Wisconsin International Law Journal 311. [ Links ]

24 Vawda 'Learning from experience: the art and science of clinical law' 2004 JJS 121. [ Links ]

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Hall & Kerrigan 'Clinic and the wider law curriculum' 2011 International Journal of Clinical Legal Education (IJCLE) 34. [ Links ]

28 Evans & Hyams 'Independent valuations of clinical education programs' 2008 Griffith Law Review 63. [ Links ]

29 Stuckey & Others supra n 11 at 189.

30 Osman 'Meeting quality requirements: A qualitative review of the clinical law module at the Howard College Campus' 2006 De Jure 276; [ Links ] Haupt 'Some aspects regarding the origin, development and present position of the University of Pretoria Law Clinic' 2006 De Jure 234; [ Links ] McQuoid-Mason 'Methods of teaching civil procedure' 1982 JJS 165; [ Links ] Vawda '"But where is the halaal food?" An appraisal of diversity teaching in clinical law programmes in South African clinics' 2008 JJS 89. [ Links ]

31 For ethical skills exercises see Albert & Gundlach 'Bridging the gap: introducing ethical skills exercises to enrich learning in first year courses' (2011) Summer Conference of the Institute for Law Teaching and Learning (ILTL) 1-10.

32 Styles & Zariski 'Law clinics and the promotion of Public Interest Lawyering' 2001 Law in Context 65; Giddings 'Contemplating the future of clinical legal education' 2008 Griffith Law Review 12; Hyams 'On teaching students to "act like a lawyer": What sort of a lawyer?' 2008 IJCLE 32.

33 Hyams 2008 IJCLE supra n 32 at 32.

34 Vawda 2004 JJS supra n 24 at 119. The clinical programmes at the University of KwaZulu-Natal are described in McQuoid-Mason 'Street law as a clinical program. The South African experience with particular reference to the University of KwaZulu-Natal' 2008 Griffith Law Review 43.

35 Hyams 2008 IJCLE supra n 32 at 32.

36 Ibid.

37 Stuckey & Others supra n 11 at 158.

38 Colon-Navarro 'Technology and assessment in the legal classroom: an empirical study' 2011 Summer Academy of the ILTL supra n 31 at 1-10.

39 Vawda 2004 JJS supra n 24 at 122; Cody & Schatz 'Community law clinics: teaching students, working with disadvantaged communities' in Bloch (ed) The Global Clinical Movement: Educating Lawyers for Social Justice (2010) 174.

40 Although the tutorial method of teaching, which can also be referred to as reflection sessions students have with their clinical supervisors, is used in clinics in the USA, the UK and South Africa, this method was only recommended as a method for imparting legal education in India in 1994; see Bloch & Prasad 'Institutionalizing a Social Justice Mission for Clinical Legal Education: Cross-National Currents from India and the United States' 2006 Clinical Law Review (CLR) 179; Lerner & Talati 'Teaching law and educating lawyers: closing the gap through multidisciplinary experiential learning' 2006 IJCLE 121.

41 Vawda 2004 JJS supra n 24 at 120.

42 Stuckey & Others supra n 11 at 195.

43 Ibid.

44 Swanepoel, Karels & Bezuidenhout 'Integrating theory and practice in the LLB curriculum: Some reflections' 2004 JJS 109.

45 Evans & Hyams 2008 Griffith Law Review supra n 28 at 64.

46 Ortiz 'Going Back to Basics: Changing the Law School Curriculum by Implementing Experiential Methods in Teaching Students the Practice of Law' 2011 available from https://works.bepress.com/damian_ortiz/1/(accessed 2016-07-17).

47 De Klerk 'Integrating clinical education into the law degree: Thoughts on an alternative model' 2006 De Jure 250; Du Plessis 'A consumer clinic as a specialised unit' 2006 De Jure 285; De Klerk & Mahomed 'Specialisation at a University Law Clinic: The Wits Experience' 2006 De Jure 306-318; McQuoid-Mason 2008 Griffith Law Review supra n 34 at 10; Haupt 2006 De Jure supra n 30 at 238-241.

48 Du Plessis 2008 JJS supra n 15 at 14.

49 Evans & Hyams 2008 Griffith Law Review supra n 28 at 67; Giddings 2008 Griffith Law Review supra n 32 at 4.

50 Research into outcomes, skills and values was undertaken across several jurisdictions and is fully described in Du Plessis (PhD thesis 2014) supra n 16 at 43-53; and Du Plessis 2015 De Jure supra n 19 at 312-327.

51 Smyth & Liddle 'Lulling ourselves into a false sense of competence: learning outcomes and clinical legal education in Canada, the United States and Australia' 2012 Canadian Legal Education Annual Review 21.

52 Munro 2002 Journal of the Association of Legal Writing Directors supra n 18 at 232.

53 Osman 2006 De Jure supra n 30 at 275.

54 De Klerk et al Clinical law in SA (2006) 266-279.

55 Kift 'A tale of two sectors: dynamic curriculum change for a dynamically changing profession' 13th Commonwealth Law Conference (2003) Developing the Law Curriculum to Meet the Needs of the 21st Century Legal Practitioner (Melbourne, Australia: Conference paper unpublished) 1-13; abstract available from http://eprints.qut.edu.au/7468/.

56 De Klerk supra n 54 at 29-262. The authors describe the skills taught, together with instruction on the teaching of the different skills. These skills are mostly taught, and instructions are aimed at teaching these skills as part of CLE courses, which form part of the LLB curriculum.

57 Chavkin 'Experience is the only teacher: Meeting the challenge of the Carnegie Foundation Report' 2007 Legal Education Digest 5. [ Links ]

58 Munro 2002 Journal of the Association of Legal Writing Directors supra n 18 at 236.

59 Identified and proposed by: the Law Society of England and Wales; see Stuckey & Others supra n 11 at 44; the State Bar of Wisconsin's Commission on Legal Education; see Findley 2006-2007 Wisconsin International Law Journal supra n 23 at 324; for the USA and Canada see the MacCrate Report; the Bar Council of India see Bloch & Prasad 2006 CLR supra n 40 at 209-212; for Australia see Giddings 2008 Griffith Law Review supra n 32 at 12; for Germany see Brücker & Woodruff 'The Bologna Process and German Legal Education: Developing Professional Competence through Clinical Experiences' 2008 German Law Journal 579.

60 Chavkin 'Matchmaker, matchmaker: Student collaboration in clinical programs' 1995 CLR 213 indicates that, in pairs, students can filter client life experiences through multiple personal life experiences and thereby potentially develop richer and more accurate understandings of their clients. Du Plessis 'Assessment challenges in the clinical environment' 2009 JJS 97 is of the opinion that there are benefits for students working in pairs, such as having a partner to discuss the case with, to plan strategy and the execution thereof together, as well as in drafting the necessary documents and correspondence. Haupt 2006 De Jure supra n 30 at 235 is also in favor of students doing the clinical component 'initially in groups, later in pairs and eventually as individuals towards the end of the course'.

61 Haupt & Mahomed 'Some thoughts on assessment methods used in clinical legal education programmes at the University of Pretoria Law Clinic and the University of the Witwatersrand Law Clinic' 2008 De Jure 278.

62 Ibid.

63 'Experiential courses ... rely on experiential education as a significant or primary method of instruction. [T]his involves using students' experiences in the roles of lawyers or their observations of practicing lawyers . to guide their learning'; see Stuckey & Others supra n 11 at 165.

64 These specialised units are: family law; refugee law; consumer law; labour law; land, housing and evictions; the law of delict; and a general unit to accommodate cases that cannot be allocated to any of the other units.

65 WLC CLE course outline (2016).

66 Ibid.

67 Ibid.

68 These specialised units are: family law; refugee law; consumer law; labour law; land, housing and evictions; the law of delict; and a general unit to accommodate cases that cannot be allocated to any of the other units.

69 UPLC CLE course outline (2016).

70 Ibid.

71 UJLC CLE course outline (2016).

72 Ibid.

73 UFSLC CLE course outline (2016).

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid.

76 The topic of legal costs is discussed in a study guide handed to the students.

77 Noone & Bloch 'Legal Aid Origins of Clinical Legal Education' in Bloch (ed) supra n 39 at 158-162.

78 Ibid.

79 Ibid.

80 See n 59 supra in this regard.

81 Ibid.

82 The seven goals were indicated in De Klerk supra n 54 at 266-279; Du Plessis supra n 19 at 312. Goal one relates to professional responsibility. The sub-goals (outcomes) are: a system of legal ethics and ethical philosophy; personal norms/morality; the professional role of legal practitioners; the analysis of legal institutions; social awareness; and affording students the opportunity to reform the system. Goal two is judgment and analytical abilities. The sub-goals (outcomes) are: recognition of relevant facts and applicable law; understanding strategy, tactics and decision making; understanding process and procedure; synthesis; and reflection. Goal three is the knowledge of substantive law. The sub-goals (outcomes) are: strengthening and deepening of existing knowledge; acquiring new knowledge; the impact of theory (strengthening and extending acquired theory); and the study of specific law areas. Goal four relates to applied practice skills. The sub-goals (outcomes) are: consultation skills; client counseling; negotiation; trial advocacy; appellate advocacy; drafting of legal documents; legal research; factual investigation; and office management. Goal five is rendering legal services to the community, which ties in with goal six where students are required to be able to learn and work in groups. Goal seven is the integration of all or some of these goals.

83 See n 59 supra in this regard.

84 See n 59 supra in this regard.

85 All these universities follow the in-house live-client model and students are required to attend weekly clinic duties, the formulation of a curriculum will focus on the classroom components of the CLE courses.