Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

De Jure Law Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2225-7160

versión impresa ISSN 1466-3597

De Jure (Pretoria) vol.46 no.4 Pretoria abr. 2013

EDITORIAL

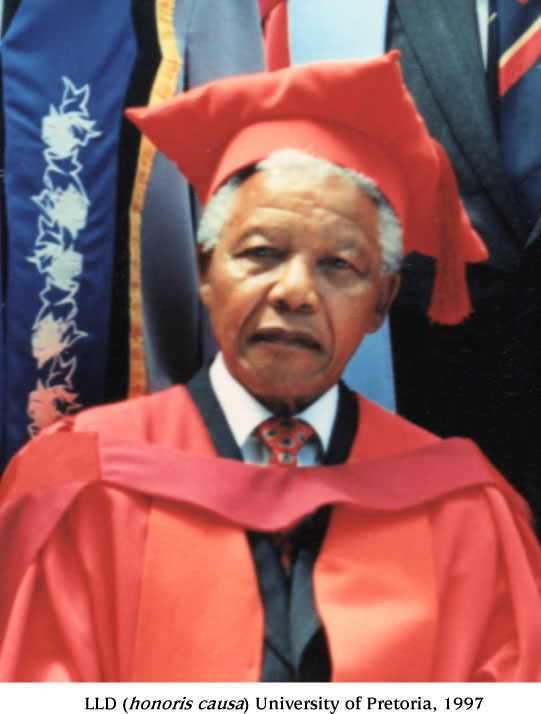

In memoriam :Speaking across generations: Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela 1918 - 2013

Christof Heyns

Professor of human rights law and former Dean, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria; United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions

Nelson Mandela had a profound impact on the Faculty of Law of the University of Pretoria, directly and indirectly; on us as a Faculty and on the world in which we operate.

In 1997 the University awarded him a doctorate in law. He used the opportunity to reach out both in Afrikaans and in English, with pathos, humility, wisdom and humour.1 This was his second time on campus. In 1991 he was supposed to speak at an event organised by students, but violence erupted and he had to be rushed off the stage.2

It is worth quoting his speech at the graduation ceremony at some length:

Dit is baie maklik om leë woorde te gebruik, en gewoon om hoflikheidsonthalwe te sê wat 'n groot eer 'n mens aangedoen word. Ek sou egter vandag wou hê dat u moet weet hoe diep geraak ek is deur hierdie eerbetoon wat u as universiteit aan my bring.

Dit is goed dat ons die verlede agtergelaat het en nie te veel daaroor tob nie. Maar miskien vergeet ons, aan die ander kant, ook te gou en te maklik hoe verdeeld en verskeurd ons was, en watter wonderlike prestasie dit was om daardie verdeeldheid sonder vernietigende bloedvergieting te bowe te kom. Hierdie byeenkoms vandag behoort ons, al is dit net vir 'n oomblik, te herinner aan die pad wat ons in hierdie kort tydjie geloop het om 'n verenigde samelewing te bou. Hierdie inrigting en sy ere-graduand kom uit sterk uiteenlopende geskiedenisse en agtergronde. Vandag is ons hier bymekaar met 'n groot mate van eensgesindheid oor die visie en ideale vir ons land en sy mense3

I am proud to be thus associated with the University of Pretoria. I am honoured to be the recipient of an award through which you are paying tribute to our nation as a whole, for their achievement in overcoming our past of conflict and division and joining hands to work for shared ideals. I humbly accept it in their name.

It is good that we have left the past behind us, and do not ponder upon it too much. But perhaps we also forget, on the other hand, too easily how divided and torn we were, and what a remarkable achievement it was to overcome that division without debilitating bloodshed. This meeting today should remind us, even if it is just for a moment, of the road that we have travelled in this short space of time to build a united society. This institution and its honorary graduate come from vastly different histories and backgrounds. Today we are here with a large degree of unanimity on the vision and ideals for our country and its people."

In its past this University had a reputation for serving a particular ideology which inflicted great suffering upon the majority in our country. Today it is a transformed and transforming institution, providing further testimony to my conviction that in spite of a political past that dealt terrible cruelty to fellow citizens with great insensitivity, Afrikaners when they change, do so completely, becoming people upon whom one can trust fully.

As our institutions transform, changing their composition to reflect the diversity of our rainbow nation, we must not be too surprised or disheartened if and when tension and conflict come to the surface, as it has on some occasions on this campus. We have not fallen from heaven into this new South Africa; we all come crawling from the mud of a deeply racially divided past. And as we go towards that brighter future and stumble on the way, it is incumbent upon each of us to pick the other up and mutually cleanse ourselves.

It has often been said in recent years that university-based intellectuals in South Africa - whether antiapartheid or apartheid supporting in thrust - had derived so much of their focus from the fact of the apartheid society, that they have now somewhat lost their way. There is a sense that the voice of the universities has fallen quiet in the larger debates of our society. That vibrancy in our intellectual life, which was so much a feature of internal challenge to apartheid, seems to have largely disappeared. One trusts that our university-based intellectuals - staff and students - will soon once more take up the role of critical partners in building and developing our new society - identifying through research, scholarship and debate the burning issues at the heart of our new society.

It is through such engagement that our national efforts of reconstruction and reconciliation, of nation-building and development, will reap the full benefit of the prestigious achievements of this university, across the disciplines.

Having been so graciously granted an honorary doctorate by yourselves does not make me you intellectual peer. And I should be very careful about treading on the domain of trained intellectuals. But let me nevertheless be so foolish as to venture a final thought.

It does seem as if South African intellectuals - whether in the universities or the media - at times allow themselves to be impeded by a fear of appearing to be co-opted. Progressive intellectuals have traditionally and rightly been very suspicious of the concept of "patriotism", so often abused by demagogues and autocrats to suppress criticism and independence of thought. One fully grants our intellectuals the right to share that attitude. Our own call - including to intellectuals - for a new patriotism is, however, not a call to compromise anyone's independence. Pride in national development and commitment to it do not stand in any necessary contradiction to critical independence. A professional fetish about "criticalness" at all costs may, on the other hand, hamper intellectuals in playing the full role they should be playing in recording, describing, analysing, evaluating and criticising our efforts at building and developing the new society.

Ek het waarskynlik nou reeds te veel gesê. Laat ek afsluit voor die Universiteit besluit om die doktorsgraad terug te trek. Nogmaals baie dankie vir hierdie groot eer. Ek is trots daarop om nou 'n lid van hierdie universiteitsgemeenskap te wees.

Ek sê dit in die volle vertroue dat hierdie inrigting sal voortgaan om sy rol te speel in die opbou en ontwikkeling van ons nuwe samelewing.4

Faculty members participated in technical groups tasked with dismantling apartheid laws as part of the transition during the early 1990s, and Johann van der Westhuizen served as one of the technical advisors who drafted the first democratic Constitution that entered into force in 1996, and in that capacity also engaged with then President Mandela.

In 1995, the Centre for Human Rights of the Faculty or Law organized the African Human Rights Moot Court Competition in Pretoria -something it would not have been able to do under apartheid. The Centre had asked the President to welcome the participants by means of a letter. The Centre still reprints Mandela's assessment of the value of the exercise in the documentation of every moot competition:5

One could hardly think of a better way to advance the cause of human rights than to bring together students - who are the leaders, judges and teachers of tomorrow - to debate some of the crucial issues of our time in the exciting and challenging atmosphere of a courtroom, where they can test their arguments and skills against one another in a spirit of fierce but friendly competition.

During the 1990s the Centre for Human Rights ran a programme called the Southern African Student Volunteers (SASVO), which placed students as volunteers at schools, which they renovated, across Southern Africa. The programme was the largest recipient of funds from the Nelson Mandela Foundation. Mandela invited the organisers to an event at his home in Pretoria and said to us: "You have no idea how much hope you are giving all of us."6 The irony and the magnanimity were unmistakable: The University of Pretoria was regarded and further encouraged to be part of the solution.

It is however the changes that Mandela brought to the world in which we live and operate that have had the most far-reaching consequences on what we can do and what kind of law faculty and university we are today.

Throughout recorded history, humanity has always been divided into clans, tribes and races that were not only exclusive, but often hostile to each other and indeed engaged in war. This was considered to be normal; it was the way things were and how they should be. War itself had not been made illegal until the last century.

This started to change with the advent of a global community. The international human rights framework was established after the Second World War and now sets the standards for domestic laws and practices. This framework - prioritising right over might - has become the new "normal", even though it often still does not reflect the real practice.

As with all major social changes, not all parts of the globe moved at the same pace. South Africa, isolated from the rest of the world and with a minority racial group in power, became the most prominent straggler. In 1948, as the rest of the world adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the then all white electorate in South Africa turned its back on them and voted into power the National Party.

If the practice of the centuries was to be the yardstick, the "normal" outcome of such a situation would at some point or another have been -as Mandela said in his acceptance speech - a bloodbath, or protracted violence. Yet, coming from a traditional background himself, Mandela captured the new ethos of inclusivity in the most dramatic way conceivable, by taking those in whose name he was jailed along with him and creating a "new normal". In so doing, the chapter was closed on the idea that the domination of one group by another was acceptable, not only in South Africa but also worldwide. Never, never, and never again. At the same time he also made it possible for the University of Pretoria to play a role as a continental and a global university.

It is clear that Mandela did not bring about these changes on his own, as he would be the first to recognise. He was in many respects the right person at the right time - the major global catalyst in creating a new right and a new wrong.

Today the Faculty of Law of the University of Pretoria - once an inward-looking and isolated institution - is functioning in an environment where it can compete and participate on the world stage. The Faculty is playing an increasingly active role on the continent, with a unique network and a range of expertise in trade law, company law, insolvency, education law, banking law, and extractive industries in an African context. The Oliver R Tambo Law Library houses the largest and most up-to-date collection of legislation, laws and legal texts from Africa. The Faculty is thoroughly engaged with the international organisations of the continent and the world, and its programmes have won the highest United Nations and African Union prizes.

The Faculty in fact now plays the role of a leader - of all things - in the area of human rights in the African continent. That is how radical the shift that was made possible has been.

In reflecting on this tale, there is something to be learned about the way in which lawyers and others, each with some part of the truth, can reach out to each other across generations and steer their society with relatively few losses through the minefields of history.

Some of the seminal political reformers of South Africa - Mahatma Gandhi, Jan Smuts; Oliver Tambo; FW de Klerk; and Nelson Mandela -have all been trained as lawyers. In many cases they have espoused views based on the mores of their times, which were then challenged by their successors. Some of their insights were rejected while others were used and elaborated upon.

Gandhi's objectives during the 21 years that he spent in South Africa were confined to advancing the cause of the Indians in South Africa, and by today's standards he would probably be regarded as a racist in his attitudes towards Africans.7 Yet he established the precedent that a brown-skinned person could stand up to a white government - and indeed later also to a colonial power - and win. The method he introduced to achieve this goal - nonviolent mass demonstrations - has become a preferred tool of political resistance in societies around the world. By offering an alternative to violent protest, or at least a restraint on its use, Gandhi established himself as one of the great civilisers of humanity.8 While few would follow his categorical commitment to nonviolence, his success through non-violence was well known and discussed by the leaders of the later struggle against apartheid, including Nelson Mandela, and is probably one of the causes of the relatively peaceful nature of the eventual transition in South Africa.9

Gandhi's main adversary - but also someone who learned from Gandhi and used his methods10 - was Jan Smuts. He was a founder of the League of Nations and the United Nations and the person who inserted the notion of human rights into the preamble of the Charter of the United Nations.11 While he promoted the idea of human rights on the world stage, his domestic policies were segregationist and at best paternalistic. However, unlike the Nationalists who beat him on the ticket of apartheid, he did not claim to have a final answer. Smuts regarded the apartheid and homelands policies the National Party as "a crazy concept, based on prejudice and fear".12 With reference to the racial issue Smuts said: "I feel inclined to shift the intolerable burden of solving that sphinx problem to the ampler shoulders and stronger brains of the future."13

Mandela as a student of the Faculty of Law at the University of Fort Hare went to listen - and by his account applauded - Smuts, when the latter spoke at Fort Hare in support of South Africa's entrance into the Second World War against Nazi Germany. Mandela recounts: "I cared more that he had helped found the League of Nations prompting freedom around the world, than the fact that had repressed freedom at home."14

A Hollywood director recreating the scene on the Fort Hare campus would probably not be able to resist the temptation to make Smuts refer in his speech to the "ampler shoulders and stronger brains" needed to address the racial issue of South Africa, and then zoom in on the young Mandela in the audience. In taking on South Africa's most difficult issue, Mandela made the methods introduced by Gandhi his own, as volunteer in charge of the 1952 Defiance Campaign which served to give the ANC national prominence. In an intriguing twist, the liberation struggle would also often rely on the international human rights system, in the introduction of which Smuts had played a key role, against Smuts's successors. In so doing, Mandela gave what at the time may have been lofty aspirations advanced by Smuts for external consumption, concrete application in South Africa.

And yet, the racial issue, like so many others, remains in many respects unresolved. South Africa and the world as a whole is still, in practice, deeply divided along racial lines. Huge discrepancies in access to resources and opportunities remain, often along racial, gender and class lines. While protesters in many countries find it possible to use peaceful demonstrations as a political tool, violence simmers below the surface, and often boils over. In Africa there are numerous obstacles in the way of unlocking our natural resources in a sustained and sustainable way. Poverty and abuse of power remain some of the greatest threats to human dignity.

Any talk about having reached our destination is grossly inappropriate. As Mandela has famously said, one reaches to the top of one hill only to find there are many others.15 To address the widespread problems that remain, further transformation is called for, which will in turn solve some problems but no doubt create new ones, before moving on. In dealing with Sphinx problems we, like Sisyphus, have to keep rolling the rock up the hill.

It is clear, looking around us in South Africa and the world, that Mandela could only address some issues, and even in those areas his legacy is incomplete and in some cases already under threat. That should not be a surprise. Hope in the long run does not rest with individuals, even exceptional ones, who come and go. Placing too much reliance on individuals and heaping unqualified praise on them undermines the responsibility and agency of the rest of the community, leaving them weak. If hope is to be found it has to come from institutions with life-spans that stretch across time. This includes the institutions that producethe people who have to face the challenges of their era. Indeed, education is the most powerful tool that one can use to change the world. It also includes institutions such as the legal profession, which has produced such outstanding leaders in our society.

The Faculty of Law of the University of Pretoria, alongside the other educational institutions of our country and the legal profession as a whole, benefited in a special way from our interaction with a truly great man. This, however, brings us only as far as the imperfect present. And the opportunities offered place a special responsibility on all of us to place our resources and resourcefulness at the disposal of our society.

The future will depend whether we use the space we have been given as a springboard to produce more people who, when their time comes, will be ready to take on the challenges of their era and their world. The future will depend on whether we who staff and steer these institutions can produce the long chain of reformers - lawyers and others -stretching across generations, who often learn from each other, and as a result have the skills to move the world beyond that which we today consider "normal". In doing so, there is ample inspiration to be found from our own history, and the remarkable voices that have spoken across generations.

1 For the full text, see http://web.up.ac.za/default.asp?ipkCategoryID=7552&subid=7552&ipklookid=10 (accessed 2013-12-17).

2 For a copy of the speech he would have presented on that occasion, see http://www.sahistory.org.za/search/apachesolr_search/University%20of%20Pretoria%201991 (accessed 2013-12-17). See also http://madiba.mg.co.za/article/1991-05-03-when-will-the-right-learn (accessed 2013-12-17).

3 Translation: "It is very easy to use empty words, and to say simply as a matter of courtesy that this is an honour. I would however want you to know today how deeply I am touched by the honour that you as a university are bestowing upon me.

4 Translation: "I have probably said too much already. Let me conclude before the University decides to withdraw the degree. Thank you once again for this great honour. I am proud now to be a member of this university community. I say this in full confidence that this institution will proceed to play its role in the construction and development of our new society."

5 http://www1.chr.up.ac.za/images/files/education/moot/2012/mc%202012%20brochure.pdf (accessed 2013-12-17).

6 http://www1.chr.up.ac.za/index.php/centre-news-2013/1246.html (accessed 2013-12-17).

7 See Lyleveld Great soul: Mahatma Gandhi and his struggle with India (2011).

8 See Heyns "On civil disobedience and civil government in South Africa" in Law, Justice and the State III (eds Soeteman & Karlsson) (1995) 133-148.

9 See Mandela Long walk to freedom: The autobiography of Nelson Mandela (1994) 77.

10 See Smuts "Gandhi's political methods" essay dated 1939-03-27, contained in the JD Pohl Collection, University of Pretoria archives.

11 See Mazower No enchanted palace: The end of empire and the ideological origins of the United Nations (2009). [ Links ]

12 Mandela op cit 71.

13 See Hancock & Van der Poel (eds) Selections from the Smuts papers vol 2 (2007) 242. [ Links ]

14 Mandela op cit 41.

15 Idem 385.