Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

De Jure Law Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2225-7160

versión impresa ISSN 1466-3597

De Jure (Pretoria) vol.46 no.2 Pretoria feb. 2013

ARTICLES

Plain packaging and its impact on trademark law*

Ongetooide Verpakking en die Impak Daarvan op die Reg Insake Handelsmerke

Louis Harms

BA LLB LLD. Adams & Adams Professor in Intellectual Property Law and Extraordinary Professor, Department of Private Law, University of Pretoria Former Deputy President of the Supreme Court of Appeal

OPSOMMING

Handelsmerke word ruim beskerm en wetgewers laat die eienaars van handelsmerke tot 'n groot mate toe om hulle handelsmerke ongestoord te gebruik. Daar is egter 'n nuwe wetgewende tendens op die horison wat 'n bedreiging inhou vir handelsmerke. Hierdie wetgewing, wat hoofsaaklik op tabakprodukte gemik is, vereis dat sodanige produkte slegs in voorgeskrewe ongetooide verpakking te koop aangebied mag word. Die verpakking is effekleurig en slegs die handelsnaam mag op die voorkant verskyn. Dit is die gevolg van riglyne uitgereik deur die Wêreld Gesond-heidsorganisasie na aanleiding van die konvensie oor die beheer van tabakprodukte. Australiê is die eerste land wat by wyse van wetgewing aan die riglyne uitvoering gegee het en hierdie wetgewing het toetsing deur die howe deurstaan. Dit wil voorkom of Suid-Afrika ook afstuur op soortgelyke wetgewing. Die gebruik van ongetooide verpakking kan egter onverwagse gevolge inhou. Vervalsing en sluikhandel word tot 'n groot mate bekamp deur die eienaars van handelsmerke wat hulle handelmerke teen misbruik beskerm. Indien tabakprodukte in ongetooide verpakking verkoop moet word, kan dit vervalsing en sluikhandel bevorder deurdat dit makliker sal wees om die verpakking na te boots en moeiliker sal wees vir die eienaars van handelsmerke om hulle regte af te dwing.

1 Introduction

Trademark owners are constantly testing the limits of their rights.1 Courts, in general, tend to be generous in protecting trademarks and legislatures incline to leave rights holders alone. Patentees, on the other hand, are under threat like rhinoceroses, everyone wishing to get a hand on the mystical value of horns and inventions. The persistent threat to monopoly rights comes not only from legislatures and courts but more particularly from sometimes myopic vocal pressure groups also known as civil society.

A notable exception to this generalisation about trademarks was the Laugh-it-Off case which dealt with dilution of trademarks.2 This is not the occasion to revisit that judgment. Others and I have done so before.

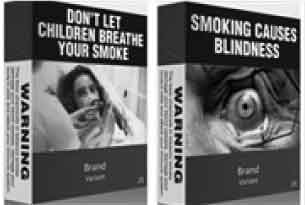

On the horizon looms a potential legislative threat to trademark law in the form of plain packaging legislation. This type of legislation typically requires that tobacco products be sold in prescribed packaging of this kind.

As appears from the illustration, the trademark may only be in the font and bland colour as indicated by the word "brand". Such limitation, one may safely assume, will be introduced through either special legislation or an amendment to health-related laws, and not by means of an amendment to the Trademarks Act.3 It will begin with tobacco products but there is a real likelihood that it will spread to other products.

Although trademarks may exist without registration, this paper is only concerned with the larger and typically more valuable category of trademarks that are registered.

2 History

I would like to begin with some history:4 When Christopher Columbus "discovered" the Bahamas in 1482 the local Caribs presented him with some tobacco leaves, presumably for smoking a peace pipe. Whether he had health concerns history does not tell us but as soon as he left the island he threw them, i.e. the leaves, overboard. His anti-smoking campaign was not a success.

Sir Walter Raleigh, a favourite of Queen Elizabeth, allegedly popularised the use of tobacco in England. He even received a royal patent for forming a colony in the New World. He called it Virginia, whether after his allegedly virgin queen or after Virginia leaf, the tobacco, I do not know. He was, unfortunately, not a- favourite of her successor, King James 1, who had him sentenced to death on two occasions. The first sentence was commuted but the second duly executed in 1618 as a favour to the Spanish throne.

Sir Walter took a pipe of tobacco shortly before he went to the scaffold. According to John Aubrey5 some "formal" people were scandalised but Aubrey thought that it was well and properly done to settle his spirits. Raleigh also left a small tobacco pouch in his prison cell engraved with an inscription: Comes meus fuit in illo miserrimo tempore ("It was my companion at that most miserable time").

There may have been another reason why King James wished him condemned: his contempt of the King's pamphlet entitled Counterblaste to Tobacco (1604). Royalty at the time was more literate than some of their contemporaries today. Henry VIII, for instance, wrote serious anti-reformation tracts before his anti-papal conversion. Reverting to James, as is apparent from the title, he abhorred tobacco smoking, chewing or snuffing. Its use embodied three sins: lust; intoxication; and "the greatest sin of all": that his subjects would spend their money on tobacco instead, as God had intended, on him.6 (Chopping off someone's head as a favour to another he apparently did not regard as sinful.)

The King concluded by referring to the use of tobacco as "a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stygian (hellish) smoke of the pit that is bottomless."

To add injury to insult the King introduced what we now call a sin tax by slapping a 4,000 per cent increase on the import duty of tobacco.

3 Tobacco Wars

One has to admire the King for his insight: he realised that tobacco was dangerous to health. What he did not know was that the tobacco family of plants is of huge scientific importance as illustrated by the fact that the CSIR is developing a drug for the treatment of rabies from one of them. Whether the American-Indian tribes will have a claim for remuneration is not clear.

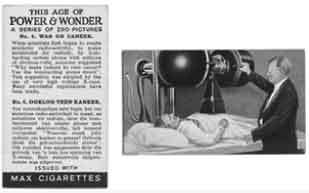

The health risks of the normal use of tobacco were only taken seriously during the 1970s when the term, "War on Cancer", came into vogue. However, a series of promotional cards in the 1930s included a card that explained how the latest cutting edge technology could help win the "War on Cancer."7

The card was in English and in Afrikaans, which tells us something about its provenance. Of special interest and ironically is the fact that it was a cigarette card issued by Max Cigarettes.

Max was a well-known brand until the mid-1950s in South Africa, produced by International Tobacco Company (ITC). Its main competitor and the dominant cigarette manufacturer at the time was United Tobacco Company (UTC). UTC's competing brands in the same price class included Springbok.

UTC began a campaign to discourage the Black population from smoking Max. It employed propagandists to spread rumours about Max. Relevant for present purposes were the allegations that Max was the wrong cigarette for Blacks to smoke; that it caused coughing; that it caused tuberculosis; and (if my childhood memory serves me right) that Max caused cancer.

In the process UTC systematically destroyed the Max mark. Litigation followed8. The court found that the statements were false, that they were made with knowledge of their falsity, and were made maliciously. An award of damages of £580,800, which translates into some R42,000,000 at present day values, was made. UTC did not prosecute an appeal.

If one would wonder why the court did not find that the cigarettes did have deleterious health effects the answer must be that UTC could hardly, without destroying its own business, seek to justify the allegations. Instead of relying on justification its case was one of general denial.

UTC in due course had its comeuppance through Rembrandt and Rembrandt's brilliant use of trademarks.

4 Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

The World Health Organisation Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC)9 is, according to the WHO, a treaty that reaffirms the right of all people to the highest standard of health and represents a paradigm shift in developing a regulatory strategy to address addictive substances. In contrast to drug control treaties this treaty focuses on demand and supply reduction strategies, and not on prohibition.

The treaty, says the WHO, was developed in response to the globalisation of the tobacco epidemic, which is facilitated through trade liberalisation, direct foreign investment, global marketing, transnational tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, and international movement of counterfeit cigarettes.

The treaty was signed by 169 countries which meant that they would strive in good faith to ratify, accept, or approve it, and show political commitment not to undermine its objectives. Notable non-signatories include the USA and Switzerland.

The treaty itself does not deal with trademarks. Of relevance for this discussion is Article 11, which requires of countries to adopt effective measures to ensure:

(i) that tobacco product packaging and labelling do not promote a tobacco product by any means that are false, misleading, deceptive or likely to create an erroneous impression about its characteristics, health effects, hazards or emissions; and

(ii) that any outside packaging and labelling should carry health warnings that should be 50 per cent or more of the principal display areas.

And then there are Guidelines. These provide that countries "should consider [I emphasise should consider] adopting measures to restrict or prohibit the use of logos, colours, brand images or promotional information on packaging other than brand names and product names displayed in a standard colour and font style."

The Guidelines add that the effect of advertising or promotion on packaging can [I emphasise can] be eliminated by requiring plain packaging: black and white or two other contrasting colours; nothing other than a brand name, a product name and/or manufacturer's name; and no logos.

The motivation for these Guidelines, it is said, is to:

[i]ncrease the noticeability and effectiveness of health warnings and messages, [to] prevent the package from detracting attention from them, and [to] address industry package design techniques that may suggest that some products are less harmful than others.

As could be expected, the treaty came in for heavy criticism from not only those with direct interests in the tobacco industry but also those on the periphery such as intellectual property lawyers and other industries that depend on trademarks. One may immediately think of the liquor industry. And one could also envisage a Coca-Cola bottle, 70 per cent covered with a picture of someone with rotting teeth. Interestingly, the Coca-Cola Company was put on trial in the USA during 1909 for selling an adulterated and deleterious product. The issue was not the fact that the product contained small quantities of cocaine or that it had large quantities of sugar, but because it contained added caffeine.10

One could also picture a McDonald's hamburger cover with a dead cow or an obese kid.11 Or a Toyota covered with pictures of blood-spattered victims of taxi accidents.

A German newspaper facetiously suggested that every male organ should carry both a health warning and one about the costs of raising an unexpected child.

The legal objections to these initiatives fall into three broad classes: (1) they are in conflict with international law; (2) they are unconstitutional; and in any event (3) they undermine basic principles of trademark law.12 For the sake of convenience I shall address the third issue first.

5 Trademark Rights

Before dealing with the rights implicated, the following has to be stressed for the sake of context. Although trademarks are intangible property, there is no constitutional right to a trademark. The rights arise through registration and although we prefer to call trademarks intellectual property they are, as we learnt already in 1883, more properly referred to as industrial property.

Like all rights, a trademark right is not absolute but relative, and may in any event be trumped by other rights.

A trademark is said to be a negative right. It is a right to prevent others from using the same or a confusingly similar trademark for the same or similar goods or services. All things being equal, its ownership gives a preferential right to use to the owner but not an absolute right to use the mark on the particular goods for which it is registered. To illustrate, simply because one holds a trademark for a prohibited substance does not mean that one is entitled to market that substance, with or without the mark.

The principles of trademark law affected by plain packaging regulation are the following:

(i) Trademarks serve as badges of origin to prevent confusion or deception as to the origin of the product.

(ii) They also have other functions, such as an advertising function by acting as silent salesmen conveying psychological messages about the merit of the product and they thereby implicitly guarantee quality.

(iii) The use principle: In order for marks to be registrable, the applicant must have the intention of using them; and if they are not used, they may be removed from the register.

There can be no doubt that plain packaging regulations based on the Guidelines make it impossible to use figurative trademarks. Well-known are for instance the camel of Camel and the red rooftop mark of Marlboro.13 These can, consequently, not be used as badges of origin.

Concerning name marks, the trademark owner is under the Trademarks Act14 entitled to use them in any manner or form or colour but regulation will limit or destroy that right. And as to confusion or deception, a mark risks losing its distinctiveness if it cannot be represented without restriction; and the less its distinctiveness the less likely it will be able to reduce or prevent confusion. Regulations requiring the same lettering, the same colour etcetera, will no doubt impinge on the distinctiveness of a trademark.

The other functions of trademarks are not protected by statute except through dilution (to the extent that it still exists) but dilution through edict such as plain packaging regulation is not actionable under the Trademarks Act.15

That brings me to a fundamental principle of trademark law, namely use: as long as the applicant has the intention to use a mark, it is registrable. It is irrelevant whether he might be prevented from using it. And as for being struck off the register, the Act has an inbuilt protection: a trademark may not be removed on the ground of non-use if that was due to special circumstances in the trade and not to any intention not to use or to abandon the trademark.

In introducing its plain packaging legislation, Australia anticipated an argument that the statute would lead to the invalidation of trademarks. The Australian statute (to which I shall return) accordingly contains savings provisions: The registrability of trademarks is not to be prejudiced by the constraints on use; and they are also not to be deprived of registrability or revoked for non-use, or because their use in relation to tobacco products would be contrary to law. These saving provisions, I believe, are inherent in our Trademarks Act.16

What this means is that trademark law does not have a number of immutable principles and that an act that imposes limitations on trademark use simply amends the Trademarks Act17 pro tanto in relation to the particular goods or services.18 Any legal attack must consequently be based on either international law (which has been internalised) or on constitutional law.

6 International Law

It is easy to make short shrift of the reliance on international law. There are two main international conventions regulating trademark law: the Paris Convention on Industrial Property of 1883 and the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) (which is part of GATT) of 1994. South Africa is a member of Paris and, by virtue of its membership of the WTO, bound by TRIPS.

The Paris Convention does not deal much with the substantive rights of trademark owners and is of no assistance.

The TRIPS agreement deals, albeit to a very limited extent, with substantive IP rights.19 However, TRIPS (and the Paris Convention) does not give rights to individuals or corporations but is only binding as between party states. It is accordingly not enforceable under national law, which means that the issue can only be raised by a tobacco exporting country against a tobacco importing country.

The issue of plain packaging has already been discussed in the TRIPS Council in 2011, and in July 2012, the Dominican Republic notified the WTO that it had launched a dispute settlement case against Australia's plain packaging law and on 9 November 2012 it requested the establishment of a WTO dispute settlement panel.20 To illustrate what upholding a complaint means, one may refer to the spat between Antigua and the USA. The WTO upheld Antigua's complaint about the ban on internet gambling by the USA and the USA failed to rectify the position. This entitles Antigua to retaliate for the $21m loss its online gaming industry is said to have suffered. It has given notice of its intention to ignore US intellectual property rights, including trademarks, to that extent.21

I do not rate the chances of success of the Dominican Republic very high. TRIPS regards a trademark right as negative right: it is the right to prevent others from using the trademark under certain circumstances. TRIPS considers the function of trademarks to be that of a badge of origin and it does not purport to deal with its subsidiary functions, such as that of silent salesman.

Although TRIPS states that the nature of the goods or services to which a trademark is to be applied may not form an obstacle to its registration, it does not say that one is thereby entitled to use such a trademark.

The only other international remedy, which is in the hands of an investor, may be found in bi-lateral trade agreements but that is country specific and a subject beyond the scope of this paper.22

7 Australia is no Longer Marlboro Country: Plain Packaging in Australia

Australia, in spite of strenuous industry opposition, was the first country to act on the Guidelines. Although its adoption of the Guidelines was said to have been done in order to comply with its international obligations that was simply posturing. There was no international obligation.

It is not necessary for purposes of this presentation to set out the detail of the Australian provisions. It suffices to state that they follow the Guidelines conscientiously and the pictorial examples illustrate their effect.23

The Commonwealth of Australia is a federation and its ability to make laws is circumscribed by its Constitution. An attack on the validity of legislation has, therefore, to be based on the allegation that the particular law is not authorised by the Constitution.

The tobacco industry sought to have the plain packaging legislation declared unconstitutional. Although, according to it, a number of IPRs were involved, I shall limit the discussion to the trademark aspect of the case.

The Australian Constitution confers upon the Commonwealth Parliament the power to make laws with respect to "[t]he acquisition of property on just terms ... for any purpose in respect of which the Parliament has power to make laws".24

The matter in due course reached the High Court of Australia.25 The essential questions for decision were, first, whether IPRs are "property" and, second, whether the limitation on the use of trademarks amounted to "the acquisition of property".

It would appear that the court was fairly unanimous in holding that trademarks are property within the meaning of the term in the section of the Constitution and entitled to constitutional protection in spite of the fact that trademark rights are negative in nature.

As to the second question the majority (6 to 1) held, I think, that trademark registration does not confer a liberty to use a trademark free from restraints found in other statutes or the general law. And although trademark rights are in substance, if not in form, denuded of their value and thus of their utility by the plain packaging provisions that does not amount to an "acquisition": rights of property may be extinguished without being "acquired".

As French CJ explained (at para 42):

Taking involves deprivation of property seen from the perspective of its owner. Acquisition involves receipt of something seen from the perspective of the acquirer. Acquisition is therefore not made out by mere extinguishment of rights.

The Commonwealth, by imposing limitations, did not acquire anything.

And he concluded as follows (at para 44):

In summary, the TPP Act is part of a legislative scheme which places controls on the way in which tobacco products can be marketed. While the imposition of those controls may be said to constitute a taking in the sense that the plaintiffs' enjoyment of their intellectual property rights and related rights is restricted, the corresponding imposition of controls on the packaging and presentation of tobacco products does not involve the accrual of a benefit of a proprietary character to the Commonwealth which would constitute an acquisition.

Matthew Rimmer, quite clearly a passionate anti-smoking fanatic, enthused that "the High Court's ruling is one of the great constitutional cases of our age."26 I would have thought, considering the issue before the court and the wording of their Constitution, that the result was fairly predictable, if not inevitable.

Rimmer added that "the ruling will resonate throughout the world - as other countries will undoubtedly seek to emulate Australia's plain packaging regime." That no doubt is correct and once again fairly predictable and early copycats predictably will be the European Union27 and South Africa. New Zealand has already given notice of its intention to adopt plain packaging legislation.

8 Constitutional Arguments

A law is unconstitutional if it impinges on an entrenched right but it will nevertheless be saved to the extent that the limitation is justifiable.

It is fair to assume that, as in Australia, any attack on plain packaging legislation will primarily be based on the property clause in our Constitution. Not being immersed in constitutional law concepts I shall keep it simple.28

According to section 25(1), no one may be deprived of property except in terms of a law of general application; and no law may permit the arbitrary deprivation of property. This provision will be of no assistance because a plain packaging law does not deprive the trademark owner of any trademark right but only regulates or limits the exercise of that right.

Section 25(2) provides that property may be expropriated only in terms of law of general application for a public purpose or in the public interest; and subject to compensation. The question then is whether a plain packaging law would amount to expropriation of property. According to our law trademarks are property, which leaves for consideration the meaning of "expropriation". Our courts interpret the word as requiring not only dispossession or deprivation but also appropriation by the expropriator (on behalf of itself or another party) of the particular right. It should immediately be obvious that although we are dealing with a provision that differs in its wording from the Australian, the result will inevitably be the same.

Assuming that I am wrong or that other provisions of the Bill of Rights might be implicated, I do believe that the limitation will be found to be justifiable. In Prince v President of the Law Society,29 a Rastafarian argued that the prohibition of the use of cannabis for religious purposes infringed his right to freedom of religion. The Constitutional Court in a split decision found that although the prohibition infringed his right the limitation nevertheless was justified on general health grounds. This, to me, is a clear indication that the Court will find that any limitation, direct or indirect, on the use of tobacco would be justifiable. The majority said:

In a democratic society the legislature has the power and, where appropriate, the duty to enact legislation prohibiting conduct considered by it to be antisocial and, where necessary, to enforce that prohibition by criminal sanctions. In doing so it must act consistently with the Constitution, but if it does that, courts must enforce the laws whether they agree with them or not.

The question before us, therefore, is not whether we agree with the law prohibiting the possession and use of cannabis. Our views in that regard are irrelevant. The only question is whether the law is inconsistent with the Constitution.

Another signpost is the refusal of the Constitutional Court to grant leave to appeal in British American Tobacco South Africa (Pty) Ltd v Minister of Health.30 The case concerned the constitutionality of a provision which states that "no person shall advertise or promote ... a tobacco product through any direct or indirect means, including through sponsorship of any organisation, event, service, physical establishment, programme, project, bursary, scholarship or any other method." The SCA held that although the provision infringed some constitutional rights (particularly that of free speech) it was, from a public health perspective, justifiable. The Constitutional Court refused to reconsider this conclusion.

9 Pampers for South Africa?

The Hungarian author, Sándor Márai, dealt with smoking addiction in this monologue:31

How do you get on with the tobacco habit? It's a struggle, isn't it? I couldn't go on - not with smoking but with the struggle. There will be a day when that too has to be faced. One adds up the facts and decides whether to live five or ten years longer by not smoking, or to surrender to this petty, shameful passion that no doubt kills but, until it does so, offers you a peculiar calming yet exciting experience. After fifty years, it becomes one of life's major questions. The answer to that question was angina and the decision to carry on exactly as before until I die. I'll not stop poisoning myself with this bitter weed because it's not worth it. You say it's not so difficult to give up? Of course it's not that difficult. I've done it before, more than once, while it was worth it. The trouble was, I'd spend the whole day not smoking. That's something else I'll have to face one day. People should resign themselves to certain weaknesses, to their need for a soporific of some sort, and be prepared to pay the price. It's so much simpler that way. Yes, but then they say: you should have more courage. My answer to them is: I may not be the bravest of men, but I am courageous enough to live with my desires.

Courageous words but we have to accept that the State has assumed the right or obligation to decide which desires are acceptable and that one should live one's life according to its dictates. In that regard the doctrine of voluntary assumption of risk is dead. One could simply refer to the history of opium without suggesting that opium and tobacco are similar.

The Chinese Emperor sought to stamp out its use in 1838. However, British traders had an interest in importing the stuff into China. They used it for barter to save payment in silver. The actions of the Emperor led to the Opium War, which China lost and the opium trade formed the basis of the fortunes of what is today a very respectable company in the Far East, Jardine-Matheson.

The use of opium for recreational purposes was socially acceptable in Europe as evidenced by the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821), an autobiographical account by Thomas De Quincey, about his laudanum addiction and its effect on his life. (Laudanum is an alcohol based drug containing opium.) Those of you who have seen the recent film, Die Wonderwerker, on the life of Eugene Marais will recall that his supplier of opium warned him that General Louis Botha, prime minister until 1919, intended to prohibit the importation of opium, the importation having been legal until then.

De Quincey's work could be compared to another classic, that of Italo Svevo: Zeno's Conscience. It is a brilliant novel, described hyperbolically as the greatest comic novel of the twentieth century, partly about a man's attempt to give up smoking. It is in that respect autobiographical: the hero, like the author, was always smoking his last cigarette. After publication and in real life the author sustained serious injuries during a car accident. Probably realising that he was close to death's door he asked for a cigarette, which he said would really be his last. For health reasons the doctor, a bit of a nanny, refused and Svevo was dead within a few hours. There is a moral somewhere but I am not sure what it is.

The choice for governments appears to be between restriction and prohibition. Prohibition, of liquor or underage sex, does not work but I do not think that this is the reason why government does not prohibit the use of tobacco.

Without being too cynical, the reason is because government does not wish to forego the resultant income.32 Our government, it would appear, earned R32 billion per annum on tobacco excise and related taxes before the increase announced on 27 February 2013.

The tension between health and state income was also underlined when the relevant health departments decided to take on advertising in the liquor industry. The Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) responded by stating that such a decision could not be taken without considering the economic impact.33 Since writing this paper Cabinet nevertheless has approved such a bill for consideration by Parliament.

It is significant is that our government, according to estimates, loses R8 billion per annum due to smuggling of cigarettes.34 The estimate for the United Kingdom is £3 billion. According to statistics released by the European Union, cigarettes and tobacco products are number 1 or 2 on the list of counterfeit products.

The leader behind the attack on the oil facility in January 2013 in Algeria was one Belmokhtar. He, it is alleged, generated millions of dollars through the smuggling of tobacco earning him the nickname "Mr Marlboro".35

There is logic behind this. Smugglers do not pay the notoriously high sin excise taxes and on that score alone make huge profits. And they run low sentencing risks compared to drug smuggling.

South Africa during February 2013 entered into a convention to contain the smuggling of tobacco products, presumably with an eye on the R8 billion. Apart from our customs and tax laws we have the Counterfeit Goods Act,36 all supposed to confine smuggling. How another convention will make a difference is difficult to comprehend.

Why do I raise all this while dealing with plain packaging? Let me begin with an analogy. It is common knowledge that Prohibition in the 1920s United States consolidated the hold of large-scale organised crime over the illegal alcohol industry and increased its other activities. Similarly, the War on Drugs, intended to suppress the illegal drug trade, instead consolidated the profitability of drug cartels.

Those at the forefront of the fight against smuggling are trademark owners. They lose more than governments. Their best weapon is a trademark. A diluted trademark is of little value and can easily be counterfeited. Trademark owners will no longer have the ability or much motivation to contain smuggling. In other words, plain packaging will lead to more counterfeiting and smuggling - and greater loss to the fiscus.

That is known as the law of unintended consequences.37

* Prestige lecture presented at the University of Pretoria on 2013-03-13. A word of appreciation to Prof David Vaver, Oxford University, for his editorial advice and to Ms Tracy Rengecas at the Centre for Intellectual Property Law for her research assistance.

1 http://www.trademarkia.com/opposition/opposition-brand.aspx (accessed 2013-03-01).

2 Laugh It Off Promotions CC v South African Breweries 2006 1 SA 144 (CC).

3 194 of 1993.

4 Lapham's Quarterly Winter 2013.

5 Clark (ed) Brief Lives: Chiefly of Contemporaries, Set Down by John Aubrey, Between the Years 1669 & 1696 189.

6 "[W]ho are created and ordained by God to bestow both their persons and goods for the maintenance both of the honour and safety of their king and Commonwealth, should disable themselves in both." (Quoted at fn 6.)

7 "The Future's War on Cancer": Smithsonian.com (accessed 2011-12-29).

8 International Tobacco Co v United Tobacco Co 1955 2 SA 1 (W).

9 WHO website http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/index.html (accessed 2013-03-01).

10 United States v Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca Cola, the Coca Cola Company of Atlanta, Georgia 241 US 265.

11 "In Fight Against Obesity, Drink Sizes Matter" http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/22/in-fight-against-obesity-drink-sizes-matter/ (accessed 2013-0301). [ Links ]

12 Halabi "International trademark protection and global public health: A just compensation regime for expropriations and regulatory takings" 2011 Cath ULR 325.

13 Phillip Morris Products v Marlboro Canada 2010 FC 109; Marlboro Canada Limited v Philip Morris Products SA 2012 FCA 201.

14 194 of 1993.

15 194 of 1993.

16 194 of 1993.

17 194 of 1993.

18 Bonadio "Plain packaging of tobacco products under EU intellectual property law" 2012 Eur IP R 599.

19 Mitchell & Voon "Implications of WTO Law for Plain Packaging of Tobacco Products" http://ssrn.com/abstract=1874593 (accessed 2013-03-01). [ Links ]

20 Saez "LDCs to Press for Extension for TRIPS, Plain Packaging Back" http://www.ip-watch.org/2013/02/26/wto-ldcs-to-press-for-extension-for-trips-plain-packaging-back/ (accessed 2013-02-26). [ Links ]

21 http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/intellectual-property-pirates-the-caribbean-8136 (accessed 2013-03-01).

22 Vadi "Global health governance at a crossroads: Trademark protection v tobacco control in international investment law" 2012 Stan J Int L 93. [ Links ]

23 http://www.yourhealth.gov.au/internet/yourhealth/publishing.nsf/content/ictstpa#.UD13jNVwVjR (accessed 2013-03-01).

24 It is the subject of the Australian film The Castle (1997).

25 JT International SA v Commonwealth of Australia; British American Tobacco Australasia Limited v The Commonwealth [2012] HCA 43.

26 http://theconversation.edu.au/the-high-court-and-the-marlboro-man-the-plain-packaging-decision-10014 (accessed 2013-03-01).

27 During September 2013, the European Parliament adopted a somewhat diluted version.

28 For a fuller discussion of expropriation principles in another context see Van der Vyver "Nationalisation of mineral rights in South Africa" 2012 De Iure 125. [ Links ]

29 2002 2 SA 794 (CC).

30 [2012] 3 All SA 593 (SCA).

31 Márai Portraits of a Marriage (translation by Szirtes (2011)) 133.

32 The case for banning is set out by Biegler at http://theconversation.edu.au/why-banning-cigarettes-is-the-next-step-in-tobacco-control-8915 (accessed 2013-03-01).

33 http://www.bdlive.co.za/business/media/2013/02/22/alcohol-advertising-ban-not-feasible (accessed 2013-03-01).

34 http://www.fin24.com/Economy/Smuggled-cigarettes-costs-R12bn-in-taxes-20121105 (accessed 2013-03-01).

35 http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/20/world/africa/in-chaos-in-north-africa-a-grim-side-of-arab-spring.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 (accessed 2013-0301). He was also known as One-Eye and was allegedly killed by the forces of Chad on 2013-03-02.

36 37 of 1997.

37 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unintended_consequences (accessed 2013-0301).