Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

versión On-line ISSN 2411-9717

versión impresa ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.123 no.11 Johannesburg nov. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/2269/2023

PROFESSIONAL TECHNICAL AND SCIENTIFIC PAPERS

Employee engagement among women in technical positions in the South Africa mining industry

N. Mashaba; D. Botha

North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa. ORCID: D. Botha http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2787-8107. N. Mashaba http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6629-5786

SYNOPSIS

The aims of this study were to investigate the factors that influence women's engagement in technical positions in the South African mining sector and to determine what could be done to promote their successful participation. A convergent parallel mixed-methods research design was used to ascertain the factors that facilitate, inhibit, and influence engagement. In the quantitative phase of the study, questionnaires were circulated to women employeees; and in the qualitative phase, semi-structured interviews were conducted with employer representatives, most of whom were human resource personnel. Confirmatory factor analysis showed that the three-factor structure (vigour, dedication, and absorption) of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale fit the sample data reasonably well. Although there is room for improvement, respondents demonstrated acceptable levels of engagement in their work. On the other hand, the qualitative findings showed that employee engagement is impacted by unfavourable working conditions, work-life balance, and the mining industry's male-dominated work culture. The findings showed that employee engagement should be elevated to a core human resource function. To increase the participation of women in mining, human resource professionals are encouraged to collaborate with mine supervisors, managers, and employees to develop programmes that promote employees' absorption in and dedication to their work.

Keywords: employee engagement, South Africa, technical mining positions, women in mining.

Introduction

One of the major challenges in the mining industry is introducing and fully integrating women into the traditionally male-dominated sector (Zungu, 2011, p.4). A male-dominated industry is defined as one that has 25% or fewer women participating in it (Catalyst, 2013). Equal participation of both men and women is critical for a country's economic growth to be effective and sustainable (Bayeh, 2016, p. 39). One of the reasons for women's underrepresentation in the mining industry is the challenge of engaging women in technical positions (AHRC, 2013, p. 3; Botha, 2013, p. 200; Campbell, 2007, p. 8; Ledwaba, 2017, p. 17; Masvaure, Ruggunan, and Maharaj, 2014, p. 488). Technical positions in mining are held by employees with some form of tertiary qualification in the frontline tasks of exploration, quantification, development, , and processing of mineral resources (Terrill, 2016, p. 16).

Engaged employees are essential for an organization - having engaged employees leads to reduced turnover, opportunities to recruit new talent, expansion of employees' knowledge base, and a competitive edge over organizations with disengaged employees (Albrecht et al., 2015, p. 7). Employee engagement is crucial for staff retention (Kundu and Lata, 2017, p. 718). For the mining industry to become a driver of inclusive economic growth, gender considerations and women's empowerment should be prioritized (BSR, 2017, p. 3). Gender equality is a human rights issue and a precondition for, and an indicator of, sustainable development (Alvarez, 2013, p. 13). Considering that women account for most of the world's poor population, prioritizing their inclusion in the workplace, especially where they are less represented, would liberate them from a life of poverty and could contribute to countries' economic growth. To achieve this, the mining industry must implement relevant measures to ensure that current employees are engaged to their fullest potential (Hughes, 2012, p. 39). Employee engagement is therefore significant for the viability and success of an organization because of its potential to positively influence the productivity, loyalty and retention of employees (Muthuveloo et al., 2013, p. 1546).

There is a gap in the literature on research into women's engagement in technical mining jobs. Previous research (Lord and Eastham, 2011; MCA, 2005; MCSA, 2019) focused primarily on the topic of attracting and retaining women in the mining industry in general, but did not consider the importance of engagement as a factor that could influence women's retention. These studies were conducted in Australia, not in the South African context. Furthermore, other studies (AWRA, 2014; Bailey-Kruger, 2012; Botha, 2013; Hutchings, e Cieri, and Shea, 2011; Khoza, 2015; Ledwaba, 2017; Nyabeze, Espley, and Beneteau, 2010; Ozkan and Beckton, 2012; van der Walt, 2008) focused on women in mining, in general, and in all occupational categories rather than only those in technical positions. Diverting attention to women employed in technical mining positions is imperative given their underrepresentation in the industry. As a result, this research sought to fill the gap in existing knowledge.

The paper begins with a theoretical framework of employee engagement and the factors that influence women's engagement in the mining industry. The research methodology, empirical results, and findings are then presented, followed by a discussion of these. Finally, key conclusions and practical recommendations for enhancing women's engagement in technical mining positions and their successful participation in the mining industry are given.

Literature review

A theoretical framework of employee engagement

Since 2002, various definitions of engagement have been proposed (Kuok and Taormina, 2017, p. 262; Leiter and Maslach, 2017, p. 55, Schaufeli et al., 2002). When Schaufeli et al. (2002) operationalized(2002) operationalised their three-factor engagement model, they noticed little attention was paid to concepts concerning the antithesis of burnout. They noted that while Kahn (1990) provided a theoretical model of the psychological presence of engagement, he did not propose an operationalization of the concept. However, Maslach and Leiter (1997) developed a theory based on the assumption that engagement is defined by three dimensions, namely energy, involvement, and efficacy, which are considered the opposites of the three burnout dimensions (exhaustion, cynicism, and lack of professional efficacy). According to Maslach and Leiter (1997, p. 17), employees become exhausted when they are overburdened emotionally and physically. When employees are cynical, they tend to be cold and distant towards their work and co-workers. Inefficacy is characterized by decreased feelings of competence and productivity at work (Maslach and Leiter, 2007, p. 368). It develops in response to an emotional exhaustion overload and is initially self-protective - an emotional buffer of detached concern (Maslach and Leiter, 2007, p. 368). This causes employees to reduce their involvement at work and even abandon their ideals (Maslach and Leiter, 1997, p. 18).

According to Maslach and Leiter (1997, p. 23), burnout is an erosion of job engagement, as what starts as important, meaningful, and challenging work turns into unpleasant, unfulfilling, and meaningless work. Employees' sense of engagement begins to diminish because of burnout, and there is a corresponding shift from these positive feelings to their negative counterparts. As a result, energy becomes exhaustion, involvement becomes cynicism, and efficacy becomes ineffectiveness (Maslach and Leiter, 1997, p. 24). Focusing on engagement signifies focusing on the energy, involvement, and effectiveness that employees bring to a job and develop through their work (Maslach and Leiter, 1997, p. 102). As a result, engagement is the positive pole, while burnout is the negative pole (Moshoeu, 2017,p. 149). Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter (2001, p. 417) define employee engagement as a persistent, positive affective-motivational state of fulfilment characterized by high levels of activation and pleasure.

In 2002, Schaufeli et al. developed a new perspective on engagement based on Maslach and Leiter's (1997) burnout theory. Schaufeli et al.'s (2002, p. 74) three-factor engagement model contends that burnout and engagement are conceptually distinct aspects that are not endpoints of some underlying continuum. Engagement is viewed through the lens of optimal human function, stressing that it is a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind characterized by vigour, dedication, and absorption (Moshoeu, 2017, p. 164; Schaufeli et al., 2002, p. 74). High energy levels, mental resilience, willingness to put effort into the work, and persistence when faced with challenges are demonstrated by vigour. Dedication can be described as a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, and pride in working for a particular organization. Absorption is attributed to a pleasant association with one's work, where time passes rapidly without one experiencing challenges with detaching oneself from work (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004, p. 295). As a result, vigour and dedication are seen as the opposites of exhaustion and cynicism (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004, p. 295). Vigour and exhaustion have been labelled as energy or activation, while dedication and cynicism have been labelled as identification. According to Schaufeli and Bakker (2004, p. 3), while burned-out employees are exhausted and cynical, engaged employees are energized and enthusiastic about their work. Professional inefficacy was omitted from the definition of engagement, as Schaufeli and Bakker's (2004, p. 5) research showed that exhaustion and cynicism are at the core of burnout, while professional efficacy seemed to play a smaller role. They noted that prior research had shown that engagement, rather than efficacy, is best defined by being immersed and happily absorbed in one's work - a state of absorption. As a result, absorption is a distinct dimension of work engagement that is not synonymous with professional inefficacy (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004, p. 295).

Schaufeli et al. (2002) developed the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) based on the assumptions of their theory. This scale was formulated based on the underlying assumption that engagement is the positive antithesis of burnout. Consequently, it is argued that the assessment of engagement and burnout should employ distinct measurement approaches. Schaufeli and Bakker (2004, p. 3) argued that assessing burnout and engagement with the same questionnaire has two drawbacks. First, they argued that it is impractical to expect both concepts to be inversely correlated. If employees are not burned out, it does not necessarily indicate that they are engaged in their work, and vice versa. Second, the relationship between burnout and engagement cannot be empirically studied when measured with the same questionnaire. Therefore, both constructs cannot be incorporated into the same model to study their concurrent validity. As a result, the UWES assesses the three dimensions of engagement (vigour, dedication, and absorption).

The UWES was used in this study to measure the engagement levels of women employed in technical positions in mining in South Africa. The application of this scale is explained in detail in the Tools and data collection section.

A contextualization of women employed in mining

The mining industry is perceived as male-dominated and often not a common or preferred field that women pursue (Botha, 2013, p. 179; Fernandez-Stark, Couto, and Bamber, 2019, p. 3). Fernandez-Stark, Couto, and Bamber (2019, p. 3) estimate that globally, women occupy approximately between 5 and 10% of jobs in the mining industry - one of the lowest levels of participation of women across all economic sectors. This has been attributed to its traditionally masculine culture, accompanied by the physically intensive labour required (Botha, 2016, p. 252).

Historical laws, policies, and traditional customs played a role in perpetuating the underrepresentation of women in mining. In May 1937, the International Labour Organization (ILO) effected the Underground Work (Women) Convention 45 of 1935, which prohibited women of all ages from being employed in any mine for underground work under article 2 (ILO, 2017). While this legislation has been revised and repealed, the ILO played a critical role in establishing labour standards. The Act was the only available template for some countries, especially European countries concerned with women's work in mining (Lahiri-Dutt, 2019, p. 5). This propagated discrimination against women in mining.

Even after the abolishment of discriminatory laws, women remain underrepresented globally. Although the mining industry is a key driver of economic growth in most countries, employment does not benefit all members of society, as it remains highly male-dominated (Armah et al., 2016, p. 471; Baah-Boateng, Baffour, and Akyeampong, 2016, p. 9; Chichester, Pluess, and TaylorTaylos, 2017). Women in mining seldom occupy core occupations that often present more employment opportunities (Abrahamsson et al., 2014, p. 20; Segerstedt and Abrahamsson, 2019, p. 617). The same applies to managerial positions, as very few women are in decision-making roles (Catalyst, 2019). In other countries, women are better equipped, as they possess the relevant qualifications and skill sets, yet they are still not permeating the industry (Daley et al., 2018, p. 91, Fernandez-Stark, Couto, and Bamber, 2019, p. 16, Purvee, 2019). This is partly due to the industry's masculine image, lack of opportunities for advancement, work environments that do not accommodate a work-life balance, and sexual harassment that prevails in the industry and is a deterrent for attracting more women, among other reasons (Cane, 2014, p. 188; Fernandez-Stark, Couto, and Bamber, 2019, p. 19; MiHR, 2016, p. 14).

In South Africa, the mining industry supports a vast number of communities through employment. At least two other jobs are created in allied industries for every direct mining job, while each mining employee supports between five and 10 dependents (MCSA, 2020). Considering the role assumed by mining in South Africa's communities, there is a notion that the industry remains of crucial importance to address the country's triple challenge of poverty, unemployment, and inequality (Fabricius, 2019, p. 2). However, the industry's progression towards achieving gender equality has been slow, as it remains male-dominated (MQA, 2020, p. 23). Currently, 17% of employees in mines are women (MQA, 2021, p. 18). Most of these women (52%) are employed in clerical support positions, and 19% are in top and senior management (MQA, 2019, pp. 13-14). Despite efforts by the Mining Charter to promote the participation of women in the industry and their advancement into management echelons, women remain a minority in non-core mining occupations, particularly in technical positions. Despite the issue of underrepresentation, the challenges faced by South African women working in mining are similar to those faced globally.

Over the years, the need to reach gender parity and holistic inclusion of women has gained prominence in the mining industry. Gender parity is adjudged as a fundamental component of sustainable development (Nayak and Mishra, 2005, p. 1). In line with the United Nations sustainable goal of achieving gender equality and empowerment of all women and girls, there is a belief that a society cannot remain healthy and achieve adequate economic well-being without the full participation of women in the different economic sectors, including mining (Nayak and Mishra, 2005, p. 2).

Factors influencing employee engagement of women in mining

The above section revealed that cultural and organizational norms in the mining industry have contributed to the underrepresentation of women in mining. The experiences of women already employed in the industry can either motivate or demotivate other women aspiring to enter the sector (Kaggwa, 2019, p. 1). The factors that influence the engagement of women employed in mining are discussed in the following subsections.

Compensation and benefits

Compared to other sectors of the economy, the mining industry is known for paying its employees higher wages than the average remuneration (Pactwa, 2019, p.10). Attractive salaries and benefits motivate women to remain engaged in their work in the mining industry (van der Walt, 2008, p. 41). In his study on job demands, job resources, burnout, and engagement of employees in the mining industry in South Africa, van der Walt (2008, p. 6) found that poor salaries and benefits could contribute to employee burnout and disengagement from work. Salaries occasionally serve as a motivating factor for employees in need of money (Ntsane, 2014, p. 26).

Career development opportunities

There is a strong association between career development and employee engagement (Guest, 2014, p. 146). Hlapho (2015:71) found that human resource development practices - such as training and development, employee feedback, career development opportunities, employee welfare schemes, and reward and recognition schemes - are key drivers of employee engagement. This assertion is supported by Ledwaba (2017, p. 60), who established that inadequate training and development prospects for women affect their morale and leave them without hope as regards growing in the mining industry. Organizations with high levels of engagement provide employees with opportunities to develop their abilities to acquire new skills and knowledge and to realize their potential (Simha and Vardhan, 2015, p. 5). Employees are more likely to commit to organizations that provide them with opportunities that facilitate career improvement (Aguenza and Som, 2012, p. 90). A lack of growth opportunities could lead to disengaged employees (van der Walt, 2008, p. 40).

Work-life balance

Work-life balance employment practice involves providing employees with an environment where they can balance what they do at work with responsibilities and interests outside the workplace (Almaaitah et al., 2017, p. 26). The mining industry has not been unsusceptible to the challenges of fostering work-life balance for employees. Work-life balance is important for employee engagement (Lockwood, 2007, p. 4). Employees are most likely to be engaged in and attached to their organizations if they recognize that their employers consider their family life (Simha and Vardhan, 2015, p. 6). The study by van der Walt (2008, p. 40) on the engagement of employees in the mining industry in South Africa revealed that a lack of work-life balance was one of the factors that led to disengaged employees. Women in mining are most likely to take advantage of employment outside the mining industry that offers them more family-friendly work environments and arrangements that provide them with less physical, more comfortable jobs with higher salaries and higher social status (Botha, 2013, p. 200).

Gender stereotyping and workplace culture

Workplace culture plays a role in employee engagement (Lockwood, 2007, p. 4; Moletsane, Tefera, and Migiro, 2019, p. 128). For employees to be engaged, an organization needs to establish its employees' feelings about their work environment (Moletsane, Tefera, and Migiro, 2019, p. 128). Effective engagement is also likely to depend on the type of organizational culture that is perceived by employees (Guest, 2014, p. 153). The overt prejudice, discrimination, and resistance towards women in mining could result in disengaged employees. The disengagement and alienation of women in mining are largely due to unequal workplace culture, the low perceived value by men, and lack of respect (AWRA, 2014). This assertion was corroborated by Hlapho (2015, p. 71), who found that the work environment and relationships with colleagues significantly affect employee engagement.

Hazardous working conditions and safety risks

The hazardous working conditions and safety risks affect women's perceptions and lead to the disengagement of those employed in the mining industry, which ultimately results in them leaving the industry as a whole (Bailey-Kruger, 2012, p. 15; Botha, 2014, p. 439; Simha and Vardhan, 2015, p.:5). Simha and Vardhan (2015, p. 5) highlight that the engagement levels of employees are affected if they do not feel secure or safe while working. Yuan, Li, and Tetrick (2015, p. 169) found that social interactions (co-worker support) and perceptions of safety practices (organizational commitment to safety) can collectively lead to high levels of engagement and safety behaviours. Therefore, organizations must implement appropriate measures to ensure equal health and safety measures for the engagement of women in mining.

Research methodology

The research was conducted from a relational epistemology perspective (the premise that relationships in research are best established through what the researcher considers appropriate for the study), a non-singular reality ontology (the assumption that there is no single reality and that all individuals have their own and unique interpretations of reality), a mixed-methods research design (integrating quantitative and qualitative research methods), and value-laden axiology (conducting research that benefits people) (see Kivunja and Kuyini, 2017, p. 35).

Sampling

Women employed in technical positions across various mining companies in South Africa were the target population for the quantitative phase of the study, while the qualitative phase focused on mining company representatives who were well-versed in issues of employee engagement. Convenience sampling (also known as availability sampling) was used to select the respondents for the quantitative phase of the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: women who possessed some form of tertiary qualification in the frontline tasks of exploration, quantification, development, extraction and ,processing of mineral resources. This included women who were employed in positions requiring technical skills within the mining value chain, such as in geology, mining engineering, metallurgical engineering, chemical engineering, electrical engineering, analytical chemistry, mine surveying, and jewellery design and manufacturing. The exclusion criteria were women who were employed in administrative and supportive positions, such as clerical, secretarial, catering, and nursing and health work. In addition, purposive and convenience sampling was used to select the participants for the qualitative phase of the research. Purposive sampling is adopted when the researcher targets individuals with specific traits that are of interest or relevant to the study (Turner, 2019, p. 11).

Moreover, non-probability sampling was used; thus the sample size could not be determined in advance. A total of 282 women in technical mining positions completed the structured questionnaire. Tthis sample size is comparable to previous studies conducted on women in mining (Botha, 2013 [156]; de Klerk, 2012 [100]; Mangaroo-Pillay, 2018 [165])1. In addition, 11 employer representatives participated in the qualitative data collection phase.

Tools and data collection

Quantitative data was collected using a web-based, self-constructed coded questionnaire. The questionnaire included two sections. Section A contained biographical questions, including age, highest qualification, marital status, having children, the requirement to work shifts, duration of employment in the mining organization, and industry and work committee involvement. For Section B, the original 17-item UWES was used to measure the women's level of engagement in their organizations. Wilmar Schaufeli provides permission on his website to use the UWES (Carnahan, 2013, p. 43). This is the commonly used measurement scale for employee engagement (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004, p. 295). The UWES contains 17 questions in total: six that measure vigour, five that measure dedication, and six that measure absorption (Carnahan, 2013, p. 43). Since as early as 1999, studies have been conducted using the UWES and have shown that the scale is a valid tool that can be used to measure employee engagement (Carnahan, 201, p. 43). According to Schaufeli and Bakker (2004), the UWES is reliable and internally consistent, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient ranging between 0.80 and 0.90. The questionnaire was distributed through different channels. Among them was Women in Mining South Africa, which distributed the questionnaire's link to women in technical mining positions in South Africa via their LinkedIn page. The questionnaire was also distributed to employees of various mines by human resource personnel, the Minerals Council South Africa, and the National Union of Mineworkers.

In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted, using an interview schedule. with employer representatives (who consisted mostly of human resource personnel) knowledgeable about employee engagement. The qualitative research participants were identified with the assistance of different mines, the MQA, and the National Union of Mineworkers. Owing to Covid-19 restrictions, participants were encouraged to participate in the interviews via video meeting platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, or Skype. Participants also had the option to respond to the interview in written format.

Data analysis and reporting

The following statistical analyses were applied in the study to provide meaning to the collected data: descriptive statistics (frequency distributions, means, and standard deviation [SD]), multivariate analysis (exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis [CFA]), comparison tests (independent t-test and analysis of variance [ANOVA]) and correlation tests (the Pearson product-moment correlation). For the qualitative analysis, thematic content analysis was done to identify and analyse patterns or themes across data sets (see Wilson and MacLean, 2011, p. For the qualitative analysis, thematic content analysis was done to identify and analyse patterns or themes across data-sets (see Wilson and MacLean, 2011, p. 551).

Ethical considerations

The Basic and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Humanities, North-West University, granted permission to conduct the research (ethics number NWU-01007-20-A7). The researcher adhered to the following ethical standards: voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, privacy, respect, no harm, and protection from undue risks (Gravetter and Forzano, 2009, p. 107; Wilson and MacLean, 2011, pp. 599, 611). Data was collected face -o-face, and all the necessary Covid-19 protocols were adhered to (e.g., permission to access the location, wearing masks, sanitizing, physical distancing, safety toolkit for fieldwork, clean and disinfected equipment, and self-monitoring for symptoms).

Limitations of the study

It was expected that the study would be subject to certain limitations. One of the limitations encountered pertained to the process of data collection. The data was gathered during the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic's lockdown restrictions. This had a significant impact on the approach, timing, and duration of data collection. At the outset, data was intended to be collected through direct interpersonal interaction. However, owing to the lockdown restrictions, not all data could be gathered through this particular method. Supplementary data collection strategies were employed, including the use of social media platforms. Owing to the system of multiple work shifts in the mines, some difficulties were encountered collecting data face-to-face. To address this challenge, appointments were scheduled to accommodate respondents with busy schedules. The data collection process was facilitated by the assistance of human resource personnel at the mines where data was collected during respondents' designated lunch breaks, when they were reporting for work, and during knock-off periods. In addition, to increase the number of respondents who participated in the study, the Mining Qualifications Authority (MQA) encouraged their registered companies to participate and assisted the researcher in obtaining access to the mines.

Furthermore, the use of the non-probability sampling technique imposed limitations as regards generalizing findings to the broader population under investigation (women occupying technical mining positions in South Africa). Consequently, the results and findings of the study are limited to the individuals who participated in the research.

Empirical results: Quantitative analysis

Biographical information

The structured questionnaire was completed by 282 women in technical mining positions, although some did not complete all sections. These questionnaires were not disregarded entirely. Only sections that were satisfactory and contained valuable and useful information were retained. As a result, the quantity of responses varied between questions. Table I presents the biographical results from the respondents.

The respondents were from eight provinces of South Africa, with the majority (38.7%; N = 109) employed in the North-Province. The Free State and the Western Cape had the least respondents (both at 1.4%; N = 4). The subsectors represented were coal mining, gold mining. platinum group metal (PGM); other mining (including iron ore, chrome, manganese, copper, phosphates. and salt), cement, lime, aggregates and sand; diamond mining and processing, and jewellery manufacturing. PGM mining had the highest representation (42.2%; N = 119), and only one respondent (0.4%) represented diamond processing.

Most respondents (45%; N = 127) fell in the age group 30-39, followed by those in the 20-29 age group (32.3%; N = 91). Only a few respondents (1.1%; N = 3) stated that they had not attended school. Post-standard 10 comprised 78% (N = 220) of those with qualifications. Most of this cohort had an honours degree (20.9%; N = 59) or an advanced diploma (16.3%; N = 46).

Just over half (51.4%; N = 145) of the respondents indicated that they were single. The majority of respondents (64.2%; N = 181) indicated that they had children and had worked for their organizations for the past one to three years (30.5%; N = 86). About a quarter (25.9%, N = 72) were involved in a work committee. Slightly more than half of respondents (54.6%; N = 154) worked on the surface and were not required to work night shifts (69.9%; N = 197).

Validity and reliability of employee engagement

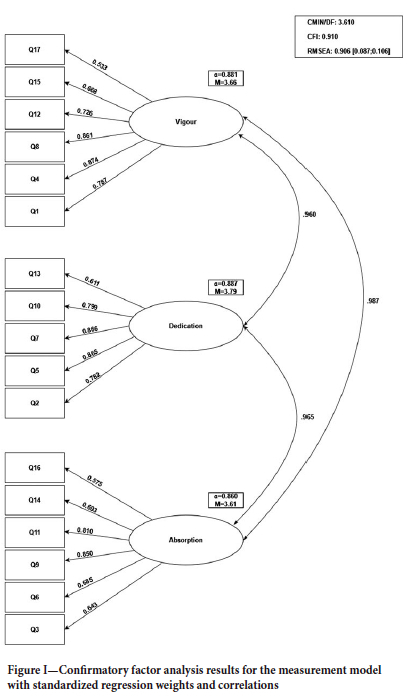

A CFA was conducted to test the structure and relationships between the latent variables that underlay the data. The results of the CFA for the measurement model with standardized regression weights and correlations are depicted in Figure 1.

The results depicted in Figure I satisfactorily support the measurement of vigour by six items, dedication by five items, and absorption by six items. All factor loadings were statistically significant at the 0.05 level. The factor loadings for vigour ranged from 0.533 to 0.874, for dedication from 0.611 to 0.866, and for absorption from 0.575 to 0.850. The commonly accepted factor loadings are those greater than 0.30 (Field, 2009, p. 631). The higher the factor loading, the greater the contribution of the variable to the factor (Yong and Pearce, 2013, pp. 80-81).

The results of the goodness-of-model-fit indices (chi-square statistic divided by degrees of freedom [CMIN/DF], Comparative Fit Index [CFI] and root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA]) yielded values that indicated an acceptable fit between the measurement model and the sampled data. The CMIN/DF obtained a value of 3.610, which is satisfactory according to Carmines and McIver (cited by Shadfar and Malekmohammadi, 2013, pp. 585-586) and Mueller (1996). The CFI was 0.910, indicating a good fit (Hair et al., 2010; Mueller, 1996; Paswan cited by Shadfar and Malekmohammadi, 2013, p. 2010; Mueller, 1996; Paswan, cited by Shadfar and Malekmohammadi, 2013, p. 585). The RMSEA value was 0.906 with a 90% confidence interval of 0.087 (low) and 0.106 (high), showing an acceptable fit (Blunch, 2008). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient values for vigour, dedication and absorption were 0.881, 0.887, and 0.860, respectively. This showed good reliability and internal consistency since Cronbach's alpha was greater than the recommended threshold of 0.70 (Child, 2006; Hair et aï., 2010; Kaiser, 1974).

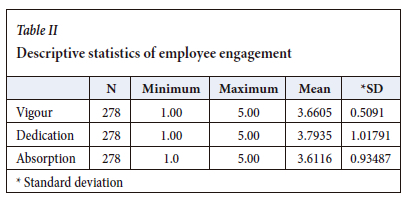

The descriptive statistics of employee engagement are presented in Table II. The response categories consisted of the following: 1 = almost never or a few times a year or less; 2 = rarely or once a month or less; 3 = sometimes or a few times a month; 4 = often or once a week; and 5 = very often or a few times a week. The research results indicate that all three factors obtained mean scores of more than 3.6. Dedication obtained the highest mean score (3.79), followed by vigour (3.66) and absorption (3.61). This indicates that the respondents showed acceptable levels of engagement (feelings of dedication, vigour, and absorption); however, there is still room for improvement.

In addition to the validity and reliability analysis, the association between the biographical variables and employee engagement was explored. The results are discussed below.

Association between biographical variables and employee engagement

Independent samples t-tests and ANOVA tests were conducted on various biographical variables to determine whether there was an association between these variables and employee engagement factors. The results of the t-tests are depicted in Table III.

Table III shows that there was no association between the requirement to work shifts and employee engagement; the p-values measured above 0.5 and the effect sizes ranged from negligible to small for all the engagement factors.

The results of the t-tests showed no significant differences between the mean scores of respondents with and without children for vigour and dedication. However, significant differences between the mean scores were found for absorption (p-value = 0.01). Respondents with children (M = 3.72) scored higher on absorption than those without children (M = 3.43); the effect size (d = 0.31) showed a small to medium effect. Therefore, respondents with children appeared to recognize absorption (a pleasant state of association with one's work in the workplace) more as a factor affecting employee engagement than respondents who did not have children.

The results of the t-tests further showed no significant differences between the mean scores of respondents involved in a work committee and those that were not for vigour and absorption. However, significant differences between the mean scores were found for dedication (p-value = 0.02). Respondents who were involved in a work committee (M = 4.03) scored higher on dedication compared to those who were not (M = 3.71); the effect size (d = 0.32) showed a small to medium effect. This implies that respondents who were involved in a work committee were more likely to show traits of dedication (having a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, and pride in working for a particular organization) than those not in a work committee.

The ANOVA test showed no significant differences between the mean scores of the marital status categories for all the employee engagement factors; the p-values measured above 0.5, and the effect sizes ranged from negligible to small.

Table IV presents the results of the correlation tests between age, highest qualification, and duration of employment in the mining organization and industry, and engagement.

Table IV shows a small negative correlation between the duration of employment in an organization and dedication (p-value = 0.008; r = -0.163). This implies that the lomger that respondents had been employed in a specific organization, the less dedicated they were to their organizations.

Empirical results: Qualitative analysis

The qualitative findings that emerged from the semi-structured interviews are presented in themes derived from transcripts. The qualitative research aimed to provide detailed information on factors that affect women's engagement in technical mining positions from the perspective of employers.

Eleven semi-structured interviews were conducted. Most of the research participants (10) were human resource personnel, except for one, who was a rock engineering superintendent. The participants were mainly from the PGM subsector,.

After gauging the participants' understanding of employee engagement, the researcher read the study's definition of the term to channel responses contextualized within the study's conceptualization.

Factors affecting employee engagement

The main factor affecting employee engagement was the lack of career development opportunities. Three participants (P1, P2, and P4) said there were few career development opportunities, such as being promoted to higher positions. They asserted that women had to work twice as hard as men to be considered for promotion. The following comments illustrate these points:

Growth opportunities within the company. But for a female, for a mother, it's a bit difficult. That person will have to almost work twice as hard as the male to get to be seen to be considered for the next level. (P1, PGM subsector)

Having few career development opportunities affects women's drive in the workplace. Career development becomes an issue. (P2, PGM subsector)

Their career growth takes longer than that of men. (P4, PGM subsector)

Other factors that were mentioned were unfavourable working conditions, work-life balance, and workplace culture (P1, P4, and P5). Women had to balance household responsibilities with work duties; sometimes, they did not even have time for themselves. In addition, the male-dominated work culture was described as intimidating, and women had to adapt and adjust to it. Some of these sentiments were expressed as follows:

Unfavourable working conditions. (P4, PGM subsector)

The mining environment is not easy for a woman. She is a mother, she's a breadwinner, and she needs to take care of the kids and the husband. They have responsibilities at home. That's demotivating in the sense that there is so much that they need to compromise for them to be able to work here and be a mother at home and to take care of responsibilities there, to the extent where you don't even have time for yourself. (P1, PGM subsector)

Male domination, the work culture of mining affects women's engagement. (P5, Other mining)

I think it is quite intimidating... and say you need to adapt... and you need to adjust to the way things are being done and the culture around here. (P1, PGM subsector)

Measures implemented by mining organizations to keep women engaged

Participants P1, P4, and P5 said their organizations provided platforms for women to express their concerns and challenges. Women used these platforms to communicate concerns they were facing at work and to raise issues that needed to be addressed to create a more suitable work environment for women. The availability of such platforms is thought to create a haven for women and make them feel valued. The following quotes indicate some of the participants' assertions of measures implemented by mining organizations to keep women engaged:

First of all, you need to recognizerecognise that you have women in he workplace. You need to give them a voice. By giving them a voice, they feel appreciated. (P1, PGM subsector)

We have created platforms where women can feel safe to talk when encountering challenges. (P4, PGM subsector)

The mine has an open platform where women can talk about issues that affect them whilst working here. (P5, Other mining subsector)

Furthermore, women were said to be protected from any form of sexual harassment (P1 and P5). Sexual harassment was not tolerated under any circumstances, and those who were found guilty of it were dismissed. The following comments demonstrate these points:

The company is going an extra mile to protect the women. In this company, for example, we recently had a sexual harassment incident from a manager's level. That person is no longer working here. We do not protect perpetrators in this environment. (P1, PGM subsector)

They are also taking legal actions against men that contravene these policies. You can even lose your job because of that. If you are a man and harassing women. (P5, Other mining subsector)

There were also initiatives in place aimed at getting women into leadership roles (P1, P3, P4, P5, P6, P8, and P11). These were implemented through programmes that encouraged employees to study further to enhance their skills. In addition, one participant (P1) stated that managers were discouraged from assigning women to night shifts to allow for work-life balance and to ensure that women were safe at work. The following assertions demonstrate these points:

Because this is a 24/7 operation, we discourage managers to put our women on night shift because of safety reasons and because we understand that they've got responsibilities at home. (P1, PGM subsector)

Women are progressing in technical management positions. (P4, PGM subsector)

There are programmes and learnerships offered in the company and skills development. (P8, PGM subsector)

Discussion

The results show that the three-factor structure (vigour, dedication, and absorption) of the UWES fit the sample data reasonably well. Cronbach's alpha coefficients showed good reliability and internal consistency for the three factors. Two goodness-of-model-fit indices (CMIN/DF and CFI) indicated a good fit, while the RMSEA indicated an acceptable fit. The mean scores of all three factors were greater than 3.6, indicating relatively acceptable levels of engagement (feelings of dedication, vigour, and absorption); however, there is still room for improvement.

The t-test and ANOVA revealed no significant differences between the mean scores of the different categories (Yes/No) for the requirement to work night shifts and marital status for the engagement factors. However, the results of the t-test and effect size revealed that respondents with children were more absorbed in their work (i.e., they had a pleasant state of association with their work in the workplace) than without children. they had a pleasant state of association with their work in the workplace) than those without children. Furthermore, the t-test and effect size showed that respondents who were involved in a work committee were more likely to exhibit traits of dedication (having a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, and pride in working for a particular organization) (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004, p. 295) than those who were not part of a work committee.

The results of the Pearson product-moment correlation revealed a small negative correlation between the duration of employment in an organization and dedication. This indicates that the more years respondents had been employed in a specific organization, the less dedicated they were to that organizations. This confirms Bakar's (2013, p. 206) finding that employees who had worked in an organization for a shorter period tendedtend to be more engaged than those who had worked there for a longer period. According to Bakar (2013, p. 206), individuals may be more excited about their work in the first few years at a company, resulting in higher engagement levels than those who have been in the organization longer. These results also align with Boikanyo's (2012, p. 73) finding that employees with zero to two years' experience were the most engaged.

The qualitative research indicated that the dearth of career development opportunities for women, such as promotion opportunities, is the major factor affecting employee engagement. The participants asserted that women had to work 'twice as hard as men' to be considered for promotion. There is a significant relationship between career development and employee engagement, as evidenced by the literature (Guest, 2014, p. 146). Hlapho (2015, p. 71) discovered that employee engagement is influenced by practices such as training and development and career advancement possibilities. Therefore, a lack of career development may result in disengaged employees (van der Walt, 2008, p. 40).

Other factors affecting engagement, according to the participants, included unfavourable working conditions, such as being required to work in hazardous or labour-intensive conditions.

Botha (2013, p. 439) and Simha and Vardhan (2015, p, 5) emphasize that employees' engagement levels will suffer if they do not feel secure or safe at work. Yuan, Li, and Tetrick, p. (2015:169) support this assertion, stating that a positive perception of safety practices (an organization's commitment to safety) is one of the factors that can contribute to high levels of workplace engagement.

Another issue affecting employee engagement is work-life balance. Participants indicated that women were expected to balance household responsibilities with work obligations, leaving little time for themselves. According to Lockwood (2007, p. 4), work-life balance is critical for employee engagement. Employees are more likely to be engaged and attached to their employers if they understand that their employers acknowledge the value of their family life (Simha and Vardhan, 2015, p. 6). Previous research on women in mining in South Africa (Botha, 2013; van der Walt, 2008) identified a lack of work-life balance as a factor contributing to disengaged employees. The lack of engagement may result in women leaving the mining industry for industries that provide more family-friendly work environments and less physically demanding jobs (Botha, 2013, p. 200).

In addition, the male-dominated work culture, to which women must adapt, affects women's engagement in technical mining positions. Women in mining are reported to feel disengaged and alienated due to unequal workplace culture, men's low perceived value of women, and a perceived lack of respect for them (AWRA, 2014). As a result, overt bias, discrimination, and resistance against women in mining may result in disengaged women employees.

Conclusion and recommendations

The study respondents, on average, showed fairly high levels of engagement (feelings of dedication, vigour, and absorption), although there is still room for improvement. The qualitative research revealed that the lack of career development opportunities, unfavourable working conditions, gender stereotyping, work-life balance, and mining's male-dominated work culture all affect engagement. These factors corresponded to those identified in the literature.

It is recommended that employee engagement be elevated to a core human resource function. Human resource professionals should collaborate with mine supervisors and managers to develop programmes encouraging employees to be more absorbed in and dedicated to their work. The emphasis, however, should not be solely on absorption and dedication. The programmes t could be constructed using Schaufeli et al.'s (2002) conceptualization of engagement, which views engagement through a positive lens, resulting in a workforce marked by a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind characterized by vigour, dedication, and absorption. Employees (both new and existing) should also be involved in developing these programmes and should be monitored regularly.

Mining organizations should accord high priority to enhancing working conditions for women and adopting work arrangements that foster a healthy work-life balance. It is advisable for mining organizations to proactively address any unfavourable working conditions that may impede women's engagement levels in the workplace, and consider the adoption of flexible working arrangements, even though mining typically has predefined systems of operation. This can be achieved using technological advancements that effectively minimize the need for manual labour. Moreover, it would be advantageous to implement daycare facilities specifically tailored for mothers with young children at mining sites. If deemed practicable, it may also be worthwhile to consider tlimiting the amount of night shift work undertaken by female employees. Moreover, mining organizations should prioritize career development to enhance women's engagement. To achieve this, it is recommended that mining companies implement measures to facilitate study assistance, mentoring, coaching, and participation in training and development programmes. By addressing these aspects, the industry can enhance its appeal to women, foster their engagement, and contribute to the mitigation of the male-dominated work culture prevalent in mining. It is recommended that human resource managers undergo training to acquire the necessary skills to effectively manage employee engagement and address any barriers that impede it.

References

ABRAHAMSSON, L., SEGERSTEDT, E., NYGREN, M., JOHANSSON, J., JOHANSSON, B., Edman, I., and Akerlund, A. 2014. Gender, diversity and work conditions in mining, mining and sustainable development. Luleå University of Technology. https://www.diva-portal.Org/smash/get/diva2:995297/FULLTEXT01.pdf [accessed 15 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Aguenza, B.B. and Som, A.P. 2012. Motivational factors of employee retention and engagement in organisations. International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics, vol. 1, no. 6. pp. 88-95. [ Links ]

AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission). 2013. Women in male-dominated industries: A toolkit of strategies. https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/WIMDI_Toolkit_2013.pdf [accessed 8 February 2019]. [ Links ]

Albrecht, S.L., Bakker, A.B., Grüman, J.A., Macey, W.H., and Saks, A.M. 2015. Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage: Anan integrated approach. Journal of Organisational Effectiveness: People and Performance, vol. 2, no. 1. pp. 7-35. doi:10.1108/JOEPP-08-2014-0042 [ Links ]

Almaaitah, M.F., Harada, Y., Sakdan, M.F., and Almaaitah, A.M. 2017. Integrating Herzberg and social exchange theories to underpinned human resource practices, leadership style and employee retention in health sector. World Journal of Business and Management, vol. 3, no. 1. pp. 16-34. https://doi:10.5296/wjbm.v3i1.10880 [ Links ]

Alvarez, M.L. 2013. From unheard screams to powerful voices: A case study of women's political empowerment in the Philippines. Proceedings of the 12th National Convention on Statistics (NCS), EDSA Shangri-La Hotel, Mandaluyong City, October. https://www.scribd.com/document/394343985/From-Unheard-Screams-to-Powerful-Voices-a-Case-Study-of-Women-s-Political-Empowerment-in-the-Philippines [accessed 12 November 2019]. [ Links ]

Armah, F.A., Boamah, S.A., Quansah, R., Obiri, S., and Luginaah, I. 2016. Working conditions of male and female artisanal and small-scale goldminers in Ghana: Examining existing disparities. The Extractive Industries and Society, vol. 3. pp. 464-474. https://doi:10.1016/j.exis.2015.12.010 [ Links ]

AWRA (Australian Women in Resources Alliance). 2014. The way forward guide to building an inclusive culture and engaged workforce. http://awra.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/WFG05_EngagedInclusive140428.pdf [accessed 20 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Baah-Boateng, W., Baffour, P.T., and Akyeampong, E.K. 2016. Gender differences in the extractives sector: Evidence from Ghana. GrOW Project: Growth in West Africa: Impacts of extractive industry on women's economic empowerment in Cote d'Ivoire & Ghana. https://www.interias.org.gh/sites/default/files/GrOW_Ghana_WP_1.pdf [accessed 20 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Bailey-Kruger, A. 2012. The psychological wellbeing of women operating mining machinery in a fly-in fly-out capacity. MA thesis, Edith Cowan University, Perth. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2683&context=theses [accessed 7 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Bakar, R.A. 2013. Understanding factors influencing employee engagement: A study of the financial sector in Malaysia. PhD thesis, RMIT University, Melbourne. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.937.4425&rep=rep1&type=pdf [accessed 19 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Bayeh, E. 2016. The role of empowering women and achieving gender equality to the sustainable development of Ethiopia. Pacific Science Review B: Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 2. pp. 37-42. https://doi:10.1016/j.psrb.2016.09.013 [ Links ]

Blunch, N.J. 2008. Introduction to Structural Equation Modelling Using SPSS and AMOS. Sage, London. [ Links ]

Boikanyo, D.H. 2012. An exploration of the effect of employee engagement on performance in the petrochemical industry. MBA dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom. http://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/8825/Boikanyo_DH.pdf?sequence=1 [accessed 16 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Botha, D. 2014. Women in mining: A conceptual framework for gender issues in the South African mining sector. PhD thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom. http://hdl.handle.net/10394/12234 [accessed 8 February 2019]. [ Links ]

Botha, D. 2016. Women in mining: An assessment of workplace relations struggles. Journal of Social Sciences, vol. 46, no. 3. pp. 251-263. https://doi:10.1080/09718923.2016.11893533 [ Links ]

BSR (The Business of a Better World). 2017. Women's economic empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa: Recommendations for the mining sector. https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR_Womens_Empowerment_Africa_Mining_Brief.pdf [accessed 20 November 2019]. [ Links ]

Campbell, K. 2007. Woman miners "no better industry", but retaining women after recruiting them seen as challenge. Mining Weekly, 3 August. https://www.miningweekly.com/print-version/039no-better-industry039-but-retaining-women-after-recruiting-them-seen-as-challenge-2007-08-03 [accessed 22 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Cane, I. 2014. Community and company development discourses in mining: Thethe case of gender in Mongolia. PhD thesis, University of Queensland, Queensland. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:345421/s41600588_phd_submission.pdf? dsi_version=31fcdc4948989de44bf6811b2f81af26 [accessed 3 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Carnahan, D. 2013. A study of employee engagement, job satisfaction and employee retention of Michigan CRNAs. PhD dissertation, University of Michigan-Flint, Flint, MI. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/143415/Carnahan.pdf?se [accessed 1 March 2019]. [ Links ]

Catalyst. 2013. Women in male dominated industries and occupations in U.S. and Canada. http://www.catalyst.org/knowledge/womenFmaledominatedFindustriesFandFoccupationsFusFandFcanada [accessed 10 February 2019]. [ Links ]

Catalyst. 2019. Women in energy - gas, mining, and oil: quick take. https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-in-energy-gas-mining-oil/ [accessed 4 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Chichester, O., Pluess, J.D., and Taylor, A. 2017. Women's economic empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa: Recommendations for the mining sector. BSR. https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR_Womens_Empowerment_Africa_Mining_Brief.pdf [accessed 5 December 2019]. [ Links ]

Child, D. 2006. The Essentials of Factor Analysis. 3rd edn. Continuum, New York. [ Links ]

Daley, E., Lanz, K., Narangerel, Y., Driscoll, Z., Lkhamdulam, N., Grabham, J., Suvd, B., and Munkhtuvshin, B. 2018. Gender, Land and Mining in Mongolia. Mokoro & PCC Mongolia, Oxford. [ Links ]

De Klerk, I. 2012. The perceptions of the work environment of women in core mining activities. MBA dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom. http://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/8670/De_Klerk_I.pdf?sequence=1 [accessed 20 November 2019]. [ Links ]

Fabricius, P. 2019. An improvement, but transformation still trumps sustainability. IRR. https://admin.irr.org.za/reports/atLiberty/files/liberty-april-2019-2014-issue-41.pdf/@@download/file/@Liberty%20April%202019%20%C3%A2%E2%82%AC%E2%80%9D%20Issue%2041.pdf [accessed 24 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Fernandez-Stark, K., Couto, V, and Bamber, P. 2019. How can 21st century trade help to close the gender gap? Background paper for WBG-WTO Global Report on Trade and Gender. https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/824061568089601224/pdf/Background-Paper-for-WBG-WTO-Global-Report-on-Trade-and-Gender-How-can-Twenty-First-Century-Trade-Help-to-Close-the-Gender-Gap-Industry-4-0-in-Developing-Countries-The-Mine-of-the-Future-and-the-Role-of-Women.pdf [accessed 3 March 2020]. [ Links ]

Field, A.P. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (and Sex, Drugs and Rock 'n Roll). 3rd edn. Sage, Los Angeles. [ Links ]

Gravetter, F.J. and Forzano, L.A.B. 2009. Research Methods for the Behavioural Sciences. Wadsworth Cengage Learning, Belmont, CA. [ Links ]

Guest, D. 2014. Employee engagement: A sceptical analysis. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, vol. 1, no. 2. pp. 141-156. https://doi:10.1108/JOEPP-04-2014-0017 [ Links ]

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., and Anderson, R.E. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th edn. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. [ Links ]

Hlapho, T. 2015. Key drivers of employee engagement in the large platinum mines in South Africa. MBA dissertation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/52407#:~:text=Job%20design%20and%20 characteristics%2C%20supervision,engagement%20on%20the%20platinum%20mines [accessed 5 August 2019]. [ Links ]

Hughes, C.M. 2012. A study on the career advancement and retention of highly qualified women in the Canadian mining industry. MA thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. https://internationalwim.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/a_study_on_the_career_advancement_and_retention_of_ highly.pdf [accessed 5 April 2019]. [ Links ]

Hutchings, K., de Cieri, H. and Shea, T. 2011. Employee attraction and retention in the Australian resources sector. Journal of Industrial Relations, vol. 53, no. 1. pp. 83-101. https://doi:10.1177/0022185610390299 [ Links ]

ILO (International Labour Organization). 2017. C045 Underground Work (Women) Convention, 1935 (No. 45). https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C045 [accessed 2 April 2020]. [ Links ]

Kaggwa, M. 2019. Interventions to promote gender equality in the mining sector of South Africa. The Extractive Industries and Society, vol. 7, no. 2. pp. 1-7. https://doi:10.1016/j.exis.2019.03.015 [ Links ]

Kahn, WA. 1990. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, vol. 4, no. 33. pp. 692-724. https://doi:10.2307/256287 [ Links ]

Kaiser, H.F. 1974. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, vol. 39, no. 1. pp. 31-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291575 [ Links ]

Khoza, N. 2015. Women's career advancement in the South African mining industry: Exploring the experiences of women in management positions at Lonmin Platinum mine. MBA dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. http://ukzn-dspace.ukzn.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10413/13777/Khoza_Nompumulelo_2015.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [accessed 15 February 2019]. [ Links ]

Kivunja, C. and Kuyini, A.B. 2017. Understanding and applying research paradigms in educational contexts. International Journal of Higher Education, vol. 6, no. 5. pp. 26-41. https://doi:10.5430/ijhe.v6n5p26 [ Links ]

Kundu, S.C. and Lata, K. 2017. Effects of supportive work environment on employee retention: Mediating role of organizational engagement. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, vol. 25, no. 4. pp. 703-722. https://doi:10.1108/IJOA-12-2016-1100 [ Links ]

Kuok, A.C. and Taormina, R.J. 2017. Work engagement: Evolution of the concept and a new inventory. Pschological Thought, vol. 10, no. 2. pp. 262-287. https://doi:10.5964/psyct.v10i2.236 [ Links ]

Lahiri-Dutt, K. 2019. The act that shaped the gender of industrial mining: Unintendedunintended impacts of the British mines act of 1842 on women's status in the industry. The Extractive Industries and Society, vol. 7, no. 2. pp. 1-9. https://doi:10.1016/j.exis.2019.02.011 [ Links ]

Ledwaba, K.S. 2017. Breaking down gender barriers: Exploring experiences of underground female mine workers in a mining company. MA dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/188775057.pdf [accessed 3 April 2019]. [ Links ]

Leiter, M.P. and Maslach, C. 2017. Burnout and engagement: Contributions to a new vision. Burnout Research, vol. 5. pp. 55-57. [ Links ]

Lord, L. and Eastham, J. 2011. Attraction and retention of women in the minerals industry: Stage one report for the Minerals Council of Australia. Curtin University. https://espace.curtin.edu.au/bitstream/handle/20.500.11937/21578/159028_37259 _Stage%20One%20Report%20MCA%20Attraction%20and%20Retention%20of%20Women%20in%20the%20 Resources%20Industry%20May%202011.pdf?sequence=2 [accessed 28 January 2019]. [ Links ]

Mangaroo-Pillay, S. 2018. The perceptions of women in the workplace in the South African mining industry. MBA dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom. http://repository.nwu.ac.za.nwulib.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/31007 [accessed 20 November 2019]. [ Links ]

Maslach, C. and Leiter, M.P. 1997. The Truth about Burnout: How Organisations Cause Personal Stress and What to Do about It. Wiley, San Francisco, CA. [ Links ]

Maslach, C. and Leiter, M.P. 2007. Burnout. Encyclopedia of Stress. 2nd edn. Fink, G (ed.). Elsevier. pp. 368-371. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303791742_Burnout [accessed 14 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W.B., and Leiter, M.P. 2001. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, vol. 52, no. 1. pp. 397-422. https://doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 [ Links ]

Masvaure, P., Ruggunan, S., and Maharaj, A. 2014. Work engagement, intrinsic motivation and job satisfaction among employees of a diamond mining company in Zimbabwe. Journal of Economics & Behavioural Studies, vol. 6, no. 6. pp. 488-499. https://doi:10.22610/jebs.v6i6.510 [ Links ]

MCA (Minerals Council of Australia). 2005. Unearthing new resources: attracting and retaining women in the Australian minerals industry. Australian Government Office for Women. https://www.csrm.uq.edu.au/media/docs/394/unearthing_new_resources_ attracting_retaining_women_australian_mining_industry.pdf [accessed 5 August 2020]. [ Links ]

MCSA (Minerals Council South Africa). 2019. Women in Mining South Africa: Fact sheet. https://www.mineralscouncil.org.za/industry-news/publications/fact-sheets/send/3-fact-sheets/738-women-in-mining [accessed 23 July 2020]. [ Links ]

MCSA (Minerals Council South Africa). 2020. Economic impact of COVID-19 lock-down on the SA economy. https://www.mineralscouncil.org.za/downloads/send/68-covid-19/946-economic-impact-of-covid-19-lockdown-on-the-sa-economy [accessed 23 July 2020]. [ Links ]

MiHR (Mining Industry Human Resources Council). 2016. Strengthening mining's talent alloy: Exploring gender inclusion. https://mihr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/MiHR_Gender_Report_EN_WEB.pdf [accessed 2 May 2020]. [ Links ]

MOLETSANE, M., Tefera, O., and Migiro, S. 2019. The relationship between employee engagement and organisational productivity of sugar industry in South Africa: The employees' perspective. African Journal of Business and Economic Research, vol. 14, no. 1. pp. 113-134. https://doi:10.31920/1750-4562/2019/v14n1a6 [ Links ]

Moshoeu, A.N. 2017. A model of personality traits and work-life balance as determinants of employee engagement. PhD dissertation, University of South Africa, Pretoria. https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/23247/thesis_moshoeu_an.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [accessed 3 October 2021]. [ Links ]

MQA (Mining Qualifications Authority). 2019. Analysis of the 2019 workplace skills plan and annual training. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

MQA (Mining Qualifications Authority). 2020. Women in mining: understanding factors that influence access and mobility in and within occupational structures in the MMS. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

MQA (Mining Qualifications Authority). 2021. Sector Skills Plan for the mining and minerals sector submitted by the Mining Qualifications Authority (MQA) to the Department of Higher Education and Training 2020-2025. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Mueller, R.O. 1996. Basic Principles of Structural Equation Modeling: An Introduction to LISREL and EQS. Springer, New York. [ Links ]

MUTHUVELOO, R., Basbous Khalit, O., Ping Ai, T., and Long Sang, C. 2013. Antecedents of employee engagement in the manufacturing sector. American Journal of Applied Sciences, vol. 10, no. 12. pp. 1546-1552. https://doi:10.3844/ajassp.2013.1546.1552 [ Links ]

Nayak, P. and Mishra, S.K. 2005. Gender and sustainable development in mining sector in India. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Purusottam-Nayak/publication/23745146_Gender_and_Sustainable_Development_in_Mining_ Sector_in_India/links/0fcfd5066823e5d918000000/Gender-and-Sustainable-Development-in-Mining-Sector-in-India.pdf?origin=publication_detail [accessed 2 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Ntsane, M.M. 2014. Factors influencing employee turnover and engagement of staff within branch network in Absa (central region). MBA dissertation, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. https://scholar.ufs.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11660/715/NtsaneMM.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [accessed 28 January 2019]. [ Links ]

Nyabeze, T., Espley, S., and Beneteau, D. 2010. Gaining insights on career satisfaction for women in mining. CIM, ICM. https://internationalwim.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Tech-Paper_MEMO_2010_Beneteau_Espley_Nyabeze_Gaining-Insights-on-Career-Sati.pdf [accessed 17 July 2020]. [ Links ]

Ozkan, U.R. and Beckton, C. 2012. The pathway forward: creating gender inclusive leadership in mining and resources. Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario.. https://www.bcctem.ca/sites/default/files/the_pathway_forward.pdf [accessed 17 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Pactwa, K. 2019. Is there a place for women in the Polish mines? Selected issues in the context of sustainable development. Sustainability, vol. 11. pp. 1-14. https://doi:10.3390/su11092511 [ Links ]

PURVEE, A. 2019. Women in engineering in Mongolia. Proceedings of World Engineers Convention 2019. https://www.wec2019.org.au/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/presentation_668.pdf [accessed 2 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W.B. and Bakker, A.R. 2004. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, vol. 25, no. 3. pp. 293-315. https://doi:10.1002/job.248 [ Links ]

Schaufeli, W.B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., and Bakker, A.B. 2002. The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, vol. 3, no. 1. pp. 71-92. [ Links ]

Segerstedt, E. and Abrahamsson, L. 2019. Diversity of livelihoods and social sustainability in established mining communities. The Extractive Industries and Society, vol. 6. pp. 610-619. https://doi:10.1016/j.exis.2019.03.008 [ Links ]

Shadfar, S. and Malekmohammadi, I. 2013. Application of structural equation modeling (SEM) in restructuring state intervention strategies toward paddy production development. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, vol. 3, no. 12. pp. 576-618. https://doi:10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i12/472 [ Links ]

Simha, B.S. and Vardhan, B.V. 2015. Enhancing "performance and retention" through employee engagement. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, vol. 5, no. 8. pp. 1-6. [ Links ]

Terrill, J.L. 2016. Women in the Australian mining industry: Careers and families. PhD thesis, UQ Business School, University of Queensland, Brisbane. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:406948/s42717773_final_thesis.pdf [accessed 24 May 2019]. [ Links ]

Turner, D. 2019. Sampling methods in research design. American Headache Society, vol. 60, no. 1. pp. 8-12. https://doi:10.1111/head.13707 [ Links ]

Van der Walt, M. 2008. Job demands, job resources, burnout and engagement of employees in the mining industry in South Africa. Honours. dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom. https://repository.nwu.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10394/5072/vanderwalt_m%281%29.pdf?sequence=1 [accessed 29 April 2019]. [ Links ]

Wilson, S. and MacLean, R. 2011. Research Methods and Data Analysis for Psychology. McGraw-Hill, London. [ Links ]

Yong, A.G. and Pearce, S. 2013. A beginner's guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, vol. 9, no. 2. pp. 79-94. https://doi:10.20982/tqmp.09.2.p079 [ Links ]

Yuan, Z., Li, Y., and Tetrick, L.E. 2015. Job hindrances, job resources, and safety performance: the mediating role of job engagement. Applied Ergonomics, vol. 51. pp. 163-171. https://doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2015.04.021 [ Links ]

Zungu, L.I. 2011. Women in the South African mining industry: An occupational health and safety perspective. Inaugural lecture, University of South Africa. Unisa. http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/5005/Inaugurallecture_ Women%20in%20the%20SAMI_LIZungu_20October2011.pdf?sequence=1 [accessed 30 January 2019]. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

D. Botha

Email: Doret.Botha@nwu.ac.za

Received: 12 Aug. 2022

Revised: 3 Sept. 2023

Accepted: 4 Sept. 2023

Published: November 2023

1 The square brackets indicate the sample size achieved