Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717

Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.121 n.11 Johannesburg Nov. 2021

PRESIDENT'S CORNER

The 1995 film 'The Englishman Who Went up a Hill but Came down a Mountain' is set in 1917, with World War I in the background, and revolves around two English cartographers arriving at a Welsh village to measure its 'mountain' to update the official maps of the region. When the cartographers conclude that the mountain is only a hill because it is slightly short of the required height of 1000 feet (305 m) for a mountain, the villagers conspire to delay their departure while they build an earth mound on top of their hill, aiming to make it high enough to rank as a mountain. The story is told humorously against the backdrop of a small Welsh community trying to save their town's honour, but underlying the machinations of the villagers, there is more. In this story, Garw Mountain symbolises the restoration of the community's war-damaged self-esteem and illustrates the importance of shared purpose and vision. We live in times of immense turmoil and uncertainty. Our decisions and actions over the next 50 years or so will determine the quality of life of the human villagers of the future.

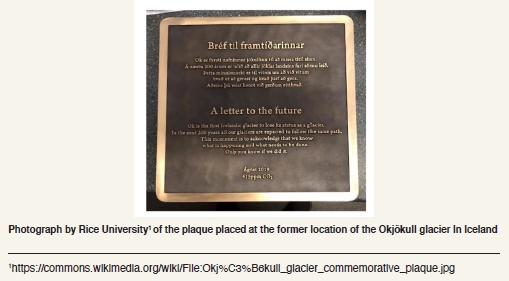

Ok (short for Okjökull) is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. Scientists agree that glaciers have disappeared from Iceland before, none as ceremoniously as Okjökull though. The once-iconic glacier melted away throughout the 20th century and was formally declared dead in 2014 by glaciologist Oddur Sigurôsson. The glacier's demise is not just a matter of shrinking area, although by 2019, less than a square kilometre remained of the more than 38 square kilometres estimated in 1901. Glaciers form from snow that becomes compacted into ice over time and the ice slowly creeps downslope under its own weight, helped along by gravity. Ok thinned so much that by 2014 it no longer had enough mass to move and became stagnant. And according to some definitions, a stagnant glacier is a dead glacier. In 2018, anthropologists Cymene Howe and Dominic Boyer of Rice University filmed a documentary about the demise of Ok ('Not Ok') and proposed that a commemorative plaque be placed to memorialize the loss as a reminder of the impact of climate change. The plaque was installed at the location of the former glacier in August 2019, with an inscription titled 'A letter to the future'. The letter to our future reads as follows:

Ok is the first Icelandic glacier to lose its status as a glacier. In the next 200 years all our glaciers are expected to follow the same path. This monument is to acknowledge that we know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.

The placement of the plaque and the letter to the future is akin to the two cartographers walking into our global village and declaring our mountain to be a hill. In the story of the Garw Mountain, in the end, the villagers prevailed; they delayed the departure of the surveyors and raised the height of the hill by working together on what seemed to be an unsurmountable problem. They succeeded because they cared and actively worked to achieve their purpose. It is said that about five years after the event when the new edition of the relevant map, which showed Ffynnon Garw Mountain at 1002 feet, was published, all the residents of the village on which the movie story was based had a copy in their homes. And for interest, according to the current Ordnance Survey covering Cardiff and Bridgend, the height of what is now known as Garth Hill is 307 metres (1007 feet), still making it a mountain. Unfortunately for Ok, we have only a plaque to remind us of what it once was, namely a majestic glacier. But we know what to do.

We hear about environmental, social, and governance (ESG) in boardrooms, at conferences, indabas, and in corporate governance reports, webinars, the press, blogs, and the SAIMM Journal's Presidential Corners. The term ESG was first coined in 2005 in a landmark study by the International Finance Corporation entitled 'Who Cares Wins'. The study made the case that embedding environmental, social, and governance factors in capital markets makes good business sense and leads to more sustainable markets and better outcomes for societies. Nearly two decades later, one may argue that we are still struggling to agree on rules, definitions, and criteria. While we grapple with definitions ('how high is a mountain?' or 'when is a glacier dead?') and whether you believe that Ok is dead, or Garth Hill is a mountain or a hill, our responsibility to the future cannot be denied and goes beyond definitions. Ultimately, whether we cared enough to succeed (who cares wins) will be measured by future generations when they come down from either a hill or a mountain. The words of Lyndon B. Johnson (36th American President) eloquently sum up what we want to achieve through the principles of ESG: '[/futuregenerations are to remember us more with gratitude than sorrow, we must achieve more than just the miracles of technology. We must also leave them a glimpse of the world as it was created, not just as it looked when we got through with it.'

I.J. Geldenhuys

President, SAIMM