Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717

Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.121 n.5 Johannesburg May. 2021

PRESIDENT'S CORNER

Are we facing a long-term commodity boom?

'The truth is never pure and rarely simple' - Oscar Wild

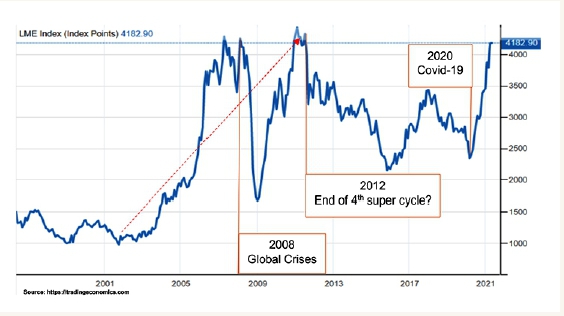

The S&P GSCI Industrial Metals Index has increased by over 86% since March 2020. The London Metal Exchange (LME) Index, which comprises aluminium (42.8%), copper (31.2%), zinc (14.8%), lead (8.2%), nickel (2%), and tin (1%), is also up by some 90% over the same periodsince March 2020. These are large jumps and one can see why our media have been speculating on the prospects of a 'super-cycle'.

A super-cycle could be described as a period of demand that remains above the overall trend for a material amount of time, and which producers find difficult to meet. Commodity prices then increase, and this can last for many years before oversupply kicks in as a consequence of miners producing more.

These types of cycles are uncommon, and only four appear to have occurred since the early 1900s.

➣ The first was a consequence of the industrialization in the USA over a relatively short period following 1910.

➣ The second started with countries re-arming prior to and during the Second World War, and continued during the rebuilding of both Europe and Japan during the 1950s and 1960s.

➣ The third cycle followed in the early 1970s in response to strong economic growth and increased prices for materials through to the early 1980s. Demand was high, but supply was disrupted as mines were nationalized and new investments dried up.

➣ The fourth and latest super-cycle started in the early 2000s when China began to modernize its economy after joining the World Trade Organization. Industrialization occurred on an unprecedented scale, together with a building boom as workers migrated to cities.

Each of the above phenomena can be linked to a large shift in global economics, and today a combination of the 2008 financial crises, Covid-19 pandemic, and fourth industrial revolution (4IR) could be the reason for the current debate.

The financial crisis of 2008 disrupted the fourth super-cycle when cash was suddenly pulled out of the system. Some of the money, already committed to projects underway, was released, but most was held back as further investments were curtailed. In addition, economic stimulus by China supported demand for only a little longer before prices started to fall again around 2012.

Capacity had, however, already increased by 2008 when we saw a build-up in inventories. Markets then traded sideways for a long time. Excess stock was consumed and we are now once again seeing a situation where above average demand is outstripping supply.

We often see commodity prices rising with inflation. Zero interest rates and low inflation have prevailed since 2008, but now fiscal stimulus and a weaker US dollar are likely to again fuel inflation. This may cause investors to hedge their positions by turning to commodities.

Then along came the Covid-19 pandemic, which may well be the catalyst for the next super-cycle. It has significantly accelerated the rate at which 4IR is changing the way we work and live around the globe. At the same time, it has impeded production globally. Covid-19 is also behind the significant economic stimulation packages recently announced. Large portions of this money will be used to support pledges by governments and private companies around the globe to strive for a net-zero carbon economy by the middle of this century (the green energy revolution). This expenditure is likely to occur over an extended period of time.

High demand, and these disruptions, could arguably drive certain commodity prices well into the future. Copper and other base metals will be needed for green energy infrastructure, while nickel, cobalt, lithium (for high-performance batteries), and aluminium (to reduce weight) will benefit from the continued rollout of electric vehicles. Of particular interest to our members is the role that PGMs and vanadium are destined to play in our re-engineered future, with the Bushveld Complex hosting one of the world's treasure troves of these great metals.

On the other hand, uncertainty prevails. The recent and dramatic increases in demand for commodities may well last for only a short period. Any increase in the cost of transporting commodities to market would reduce prices, and cash flow volatility is always a concern. Recent cash flows into gold have already started to reverse, and this shows how quickly cash can flow back out again.

Clarity and understanding come with hindsight, and this is also true for super-cycles. Increased demand, fiscal stimulus, and government spending may well support a super-cycle, but many of my associates believe that it is simply too early to call and that we won't really know until after the fact.

The only certainty is uncertainty. As our Chinese friends say: 'may you live in interesting times'. Brace yourselves, dear colleagues, for the rollercoaster ride of your lives!

V.G. Duke

President, SAIMM