Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717

Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.120 n.3 Johannesburg Mar. 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/666/2020

PAPERS OF GENERAL INTEREST

Work stress of employees affected by skills shortages in the South African mining industry

M. Thasi; F. van der Walt

Central University of Technology, Bloemfontein, South Africa. ORCiD ID: F. Van Der Walt: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6110-0716

SYNOPSIS

Skills shortages in core occupational categories in the South African mining industry have reached crisis proportions. The reason for this is that the demand for qualified individuals exceeds the supply. The result is that available employees are overburdened with duties and responsibilities. To curb the current exodus of qualified employees, such as artisans and engineers, mining companies need to consider the wellbeing of these individuals. This study investigated the work stress of employees affected by skills shortages at selected gold mines in South Africa. A descriptive quantitative research design was employed. Convenience sampling was used, and the final sample consisted of 188 artisans and engineers. The respondents indicated that they do experience work-related stress. Occupational aspects that were statistically significantly related to work stress were the physical work environment, career-related issues, and HR policy, especially pertaining to remuneration and fringe benefits. The findings of the study deepen the understanding of work stress of employees employed in occupational categories where skills shortages exist. The findings suggest that mining companies nationwide need to place increased focus on the wellbeing of their employees, so as to prevent further skills shortages in this industry.

Keywords: work stress, skills shortages, mining industry, artisan, engineer.

Introduction

Skills shortages are widely regarded as a key factor preventing economic growth rate targets in South Africa from being achieved (Erasmus and Breier, 2009). One industry that makes a significant contribution to the national economy, as well as the economy of the African continent, is South Africa's mining industry (Chamber of Mines of South Africa, 2013). Unfortunately, this industry is currently experiencing critical skills shortages in occupational categories which form part of the core business, such as engineers (Khalane, 2011) and artisans (Oberholzer, 2010). Employees working in occupations affected by skills shortages are often burdened with additional duties and responsibilities, and thus may be more prone to work stress, which could possibly adversely affect their mental health and optimal functioning. Masia and Pienaar (2011) refer to research that has confirmed that role overload, role ambiguity, and role conflict are indicative of work stress. Work stress is a complex and dynamic phenomenon, in which various factors, or stressors, and modifying variables interact (Siegrist, as cited in Ogiiiska-Bulik, 2005). It is possible that employees working in occupational categories affected by skills shortages are experiencing work stress, due to the overburdening of their internal and/or external resources. Therefore, the current study represents an attempt to contribute to managers' understanding of skills shortages, which will assist them to address human resource issues more effectively.

Skills shortages have been scientifically investigated in sectors such as construction (Bennett and McGuinness, 2009) and information technology (Wickham and Bruff, 2008), but the topic has not yet been adequately studied within the context of the mining industry. A study conducted by Paten (2006) in the construction industry found that stress levels of respondents were attributed to inadequate staffing, leading to role overload, which was one of the major causes of occupational health issues. Furthermore, previous studies investigating skills shortages have focused mainly on the economic impact (e.g. Bennett and McGuinness, 2009; Razzak and Timmins, 2008). Apart from the economic impact of skills shortages, however, one needs to ask the question 'Where do skills shortages leave employees who need to do the work in occupational categories affected by these shortages?' It is important to ask this question, as the mental health of individuals working in male-dominated industries, such as mining, has received increased interest due to the high incidence of suicide in these industries (Considine et al., 2017). Therefore, from a mental health perspective, there is a need to extend the current literature on work stress in occupations where skills shortages are experienced.

Research aim, objectives, and hypotheses

The research objective of the study was to determine whether the occupational aspects of organizational functioning, job-related tasks, the physical work environment, career-related issues, social issues, and HR policy influence the experience of work stress by employees in occupational categories where skills shortages are prevalent. The research hypotheses for the study are that the following factors have statistically significant relationships to the experience of work stress.

H1: Organizational functioning

H2: Job-related tasks

H3: The physical work environment

H4: Career-related issues

H5: Social issues

H6: HR policy.

The study addresses the current dearth of empirical research focusing on stress within the context of the mining industry. Apart from the theoretical contribution of the study, the findings regarding the experience and causes of work stress can be useful to mining companies for redesigning current retention strategies and wellness programmes. Retaining competent employees and increasing their mental health and happiness increases productivity and reduces costs (Carmichael et al., 2016), which is currently much needed in the South African mining industry.

Literature survey

Stress

South Africans from all walks of life experience abnormally high stress levels compared to the rest of the world, and these high stress levels often manifest in emotional behaviour (van Zyl and Bester, as cited in Oosthuizen and van Lill, 2008). Del Fabbro (2012) asserts that high stress levels cause employees to be less able to manage their emotions and to deal with pressure, and to be more likely to act destructively. Furthermore, problem-solving and decision-making skills are impaired, and the immune system is negatively affected, leading to more illnesses and prolonged recovery periods, which all have an adverse impact on productivity (Del Fabbro, 2012). Notwithstanding these negative outcomes associated with severe stress, stress is a natural part of everyday living, and it has become an integral part of jobs in every sector. However, if not managed effectively, work stress can have a negative effect on the physical and the emotional wellbeing of an individual (Hasnain, Naz, and Bano, 2010). Although some circumstances may have a detrimental effect on the wellbeing of an individual, the individual's perception of the situation will determine whether the situation will be stressful or not (Hasnain, Naz, and Bano, 2010). Furthermore, potential stress will become actual stress only if the outcome is both uncertain and important (Robbins et al., 2009). Thus, although stress is often regarded as negative, it can also be a positive force, enabling individuals to reach their full potential.

Work stress

Stress in the workplace is a growing concern in the current state of the global economy, where employees increasingly face conditions of overwork and job insecurity, low levels of job satisfaction, and a lack of autonomy. Work stress manifests in harmful physical and emotional responses that occur when job requirements do not match the employee's capabilities, knowledge, skills, resources, and needs, and also the expectations of the employer (Negi, 2014). Furthermore, work-related stress occurs when there is a mismatch between the demands of the job and the resources and capabilities of the individual worker. Work stress has been shown to have a detrimental effect on the health and wellbeing of employees, as well as on workplace productivity and profits (Bickford, 2005). A number of factors can lead to stress reactions in the workplace, and these factors are often referred to as stressors. Stressors can be categorized as extra-organizational stressors, organizational stressors, group stressors, and individual stressors (Luthans, 2002; Velnampy and Aravinthan, 2013). In combination or individually, these stressors may impinge upon employees at every organizational level, and in every type of organization (Velnampy and Aravinthan, 2013).

Problems outside of the work environment can also contribute to stress and make it difficult for the individual to cope with the pressures of work, and can prevent optimal performance (Gibbens, 2007). Various factors within an organization can cause a person to experience stress, such as task demands, physical demands, role demands, and interpersonal demands (Robbins et al., 2009). Group pressures, in contrast, include aspects such as pressure to increase or to limit output and pressure to conform to the group's norms (Griffin and Moorhead, 2012). If the individual's expectations differ from those of the group, they may experience high levels of stress, because they will often be excluded from group interactions or they will not experience group acceptance and support (Coopmans, 2007). On a personal level, individual dispositions also tend to moderate the effect that stressors have on an individual's health (Luthans, 2011; Quick and Nelson, 2009). Examples mentioned of such individual dispositions are Type A and Type B personalities, learned helplessness, self-efficacy, psychological hardiness, and optimism.

Schutte, Edwards, and Milanzi (2012) assert that the South African mining industry is rife with stress and difficult working conditions, despite the strategic drive to reduce injuries and ill-health. These difficult working conditions include challenging physical and cognitive job demands and the presence of hazardous materials, which have the potential to cause workplace accidents, injuries, and fatalities, making the mining industry one of the most dangerous and hazardous occupational settings in South Africa (Smit, de Beer, and Pienaar, 2016). However, despite the stressful nature of this industry, there is a dearth of research studies focusing on stress in this context (Schutte, Edwards, and Milanzi, 2012). Therefore, it is necessary to further investigate work stress in the South African mining industry. For the purposes of this study, experiences of work stress and work-related causes of stress were measured. The following work-related causes of stress were considered (Schaap and Kekana, 2016):

> Organizational functioning, which refers to employees' contribution to decision-making and strategy creation, supervisory or managerial trust, an effective organizational structure, a positive management climate, recognition, and the degree of openness in communication between employees and supervisors or managers.

> Job-related tasks, or task characteristics, which comprise the extent to which employees can control their work, adequate rewarding of executing work challenges, the quality of instruction received for a task, the level of autonomy given to employees, reasonable deadlines, utilization of employees, and work variety.

> Physical working conditions, which are aspects such as (in)adequate lighting, the temperature and the cleanliness of the work area, the availability of adequate office equipment, and the distance to and the condition of the bathrooms.

> Career opportunities, which refers to employees' expectations regarding further training and development, utilization of skills and talents, and job security.

> Social issues, which include employees' experience of social interaction at work, expectations with regard to job status, positive relationships with others, and reasonable social demands.

> HR policy, especially pertaining to remuneration and fringe benefits. Remuneration expectations refer to a fixed, a commission-based or a piece-rate salary, and a fair HR policy on remuneration. Fringe benefits include any tangible or intangible rewards that a company offers its employees.

From the mentioned research findings, one may expect that the challenging physical working conditions evident in the South African mining industry will be the main predictor of the prevalence of work stress in this industry.

Skills shortages

'Skills shortages' seems to be a somewhat vague concept, involving many specific components, but the core issue is that the demand for certain skills exceeds the supply of such skills (Daniels, 2007). Authors are not all in agreement on the definition of skills shortages, and therefore the concept has been defined differently, seemingly depending on the individual authors' areas of interest. For example, economists focus mostly on skills shortages and their relationship to productivity (Sebusi, 2007), while South Africa's Department of Labour does not make reference to this relationship (South Africa, 2006). The Department of Labour defines skills shortage as a situation in which employers are unable to fill, or experience difficulty in filling, vacancies in a specific occupation or field of specialization, due to an insufficient number of workers with the required qualifications and experience (John, 2006). For the purposes of this study, the latter definition will be used.

Core skills are applicable to occupations that form part of the core production and operations of an organization. These core skills, or core positions, are essential to an organization, and without them the organization cannot function (South Africa, 2008). Currently, critical skills shortages in South Africa's mining industry are experienced in the occupational categories of engineer and artisan (Oberholzer, 2010; Toni, 2009). Only a limited number of qualified engineers and artisans are currently available to occupy these positions, which may potentially have an adverse impact on their work experiences and organizational performance. Because engineers and artisans are part of the core business of the mining industry, shortages in these occupational groups are a burden. Not only do such shortages affect the performance of the industry and the country's economic growth rate, but they may also potentially have a detrimental impact on individuals working in occupational categories where skills shortages are experienced. Therefore, it is important to investigate how stressed individuals are within occupational categories affected by skills shortages, in order to deal with potential wellness issues before the problem of skills shortages worsens.

Methodology

Research design

A descriptive quantitative research design was used. The study was cross-sectional in nature because the research was carried out at a specific point in time on a sample from two mining companies.

Population and sampling strategy

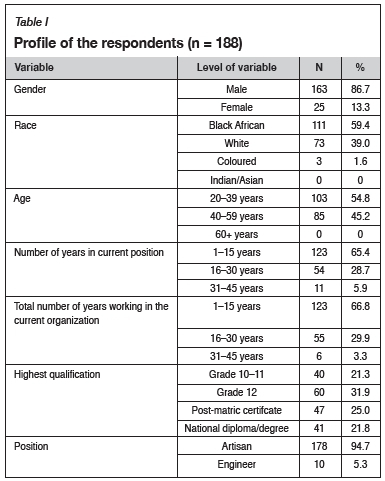

Two mining companies agreed to participate in the study. A sample was drawn from two core mining-sector occupational categories, namely artisans and engineers, because these occupational categories are severely affected by skills shortages. A total of 43 engineers and 1015 artisans were employed at these mining companies at the time the data was collected. Only readily accessible respondents could participate in the study, and therefore the convenience sampling method was used to draw a sample from the target population. The final sample consisted of 188 artisans and engineers. A description of the sample is presented in Table I.

From the information presented in Table I, the sample may be described as mostly male, black African, falling within the age category of 20-39 years, having a Grade 12 or higher qualification, and having worked for 1-15 years in their current positions and at the current organization. Although the sample is skewed towards the position of artisan, the population included 43 engineers and 1015 artisans, and the sample may therefore be regarded as representative of the population.

Data collection procedure

Primary data was collected by means of self-administered questionnaires. The questionnaires were personally distributed and collected by the researcher at a pre-arranged time on a prearranged day. Attached to the research questionnaire was an introductory letter, in which the purpose of the study was clearly stated. The questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section consisted of a self-constructed biographical questionnaire which was designed to solicit relevant demographic information from respondents regarding their gender, race, age, work experience, highest academic qualification, and their occupation, in order to describe the sample. The second section consisted of an abridged version of the Work and Life Circumstances Questionnaire (WLQ) (van Zyl and van der Walt, 1991). This section of the questionnaire consisted of 100 items, and was aimed at measuring the levels of stress that an employee may be experiencing, and identifying the causes of stress within the work situation (van Zyl and van der Walt, 1991). The following causes of stress within the work situation were investigated: the functioning of the organization, the characteristics of the tasks to be performed, the physical working conditions and the job equipment, social and career issues, and HR policy, especially pertaining to remuneration and fringe benefits. A sample item is 'How often in your work do you feel worried?' The respondents were required to rate how often at work they experience each item, where the possible responses range from 1 ('virtually never') to 5 ('always'). The third section consisted of an open-ended question to gain insight into engineers' and artisans' perceptions of the impact of skills shortages on their experience of work stress. This question gave respondents the opportunity to articulate their perceptions of the impact of skills shortages on work stress.

Instrument validation and piloting

Regarding validity, content validity was considered. Content validity was ensured by assessing the questionnaire to establish whether the questions posed were clearly formulated and concise. Two experts, an industrial psychologist and a human resource management specialist, evaluated the statements in the questionnaire to establish whether they were appropriate to measure work stress. A research psychologist also reviewed the questionnaire in terms of its content, format, and layout. Note should be taken that the WLQ is classified as a psychometric test by the Health Professions Act, Act 56 of 1974, Notice 155 of 2017 (South Africa, 2017). This implies that the psychometric properties of the test have been confirmed for a South African sample.

Before the final questionnaire was distributed to the sample, a group of 10 individuals participated in a pilot study. The individuals were requested to complete the questionnaire and to provide critical feedback, general comments, and/or advice, to ensure that the wording of the questionnaire was understandable and that the layout was appropriate. In addition, feedback was given on the time it took to complete the questionnaire. All the pilot study questionnaires were returned, comments were considered, and amendments were made.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the hosting university.

Furthermore, in order to obtain informed consent from those parties that would be affected by the study, the following criteria were met, in accordance with the suggestions of Welman, Kruger, and Mitchell (2005). Written permission was requested from the respective mining companies to conduct the research study. In order to obtain informed consent from the respondents, an introductory letter explaining the purpose of the research project was composed and attached to the final questionnaire. The introductory letter made specific reference to respondents' right to confidentiality, anonymity, and voluntary participation. At the end of the questionnaire, respondents were requested to provide their contact details if they wanted to receive a copy of the results.

Data analysis

To test the hypotheses, a variance-based approach to structural equation modelling (SEM), namely partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), was used. The statistical software program used was SmartPLS version 3.2.8. Variance-based structural equation modelling software such as SmartPLS provides robust results in complex models assessed using small sample sizes (Hair, Ringle, and Sarstedt, 2011). In this study, the six independent variables were measured using 50 items, while the sample size was 188 respondents. Before testing the hypotheses, the measurement model was assessed for internal consistency and construct validity (Hair et al., 2006). The assessment of internal consistency reliability entailed calculating the Cronbach's alpha value and the composite reliability (CR) value for each construct. The Cronbach's alpha value represents the 'conservative' estimate of reliability, and the CR value represents the 'liberal' estimate of reliability. Therefore, the true reliability of a scale lies between the Cronbach's alpha and the CR value of the scale. For evidence of internal consistency reliability, the Cronbach's alpha value and the CR value should be 0.7 or higher. Hair et al. (2006) assert that Cronbach's alpha values of 0.6 to 0.7 are deemed the lower limit of acceptability. To assess convergent validity, the outer loadings must be 0.7 or higher and must be statistically significant (p < 0.05 [two-tailed]). Also, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct must be 0.5 or higher. However, items with loadings between 0.4 and 0.7 should be considered for removal only when the removal of the item(s) would increase the reliability values and/or the AVE of the associated construct above the minimum values. To assess discriminant validity, the Fornell-Larcker criterion was applied. The Fornell-Larcker criterion entails comparing the square roots of the AVEs of two constructs with the correlation between the two constructs. For evidence of discriminant validity, the square root of the AVE of each of the two constructs forming a pair must be higher than the correlation between the two constructs.

To test the hypotheses, the bias-corrected accelerated bootstrapping procedure was used to calculate t-values and p-values (two-tailed) (Hair et al., 2006). Acceptance of a hypothesis was based on the following decision criteria: (1) The sign of the path coefficient must be in the hypothesised direction, and (2) the p-value (two-tailed) must be equal to or less than 0.05.

Findings

Assessment of the measurement model

In line with the data analysis procedure described in the previous section, the original measurement model of the independent variables was assessed for reliability and validity. However, although the assessment of the measurement model confirmed internal consistency reliability, the AVE of the six independent variables did not exceed 0.5. To achieve acceptable convergent validity, followed by discriminant validity, items with a low outer loading were systematically removed until the AVE of each factor exceeded 0.5 and discriminant validity could also be proved. In Table II the measurement model results are presented for the modified measurement model, which met the requirements for internal consistency and convergent validity.

Next, the discriminant validity of the measurement model was assessed. As seen in Table III, the square root of the AVE of each construct forming a pair is higher than the correlation between the two constructs. Thus, based on the results presented in Table III, it can be concluded that the modified measurement model also exhibits adequate discriminant validity, and the hypothesis testing can thus be performed.

Testing of the hypotheses

In Figure 1 the results of the testing of the hypotheses are summarized. As seen in Figure 1, the six independent variables explain 41.5% of the variance in the dependent variable (experience of work stress). Of the six independent variables, three variables have a statistically significantly influence on the experience of work stress - two factors exerted a negative influence, and one factor exerted a positive influence. Thus, H1, H4, and H5 are rejected, and H2, H3, and H6 are accepted. According to the results reported in Figure 1, remuneration, benefits, and policy had the strongest negative statistically significant influence on experience of work stress (-0.312; p = 0.001 [two-tailed]). Job-related tasks also had a negative statistically significant influence (-0.263; p = 0.002 [two-tailed]. In contrast, physical work environment was the only factor that had a statistically significant positive influence (0.233; p = 0.042 [two-tailed]) on experience of work stress.

Perceived relationship between work stress and skills shortages

In order to determine the perceptions of respondents employed in core occupational categories (i.e. artisans and engineers) regarding the impact of skills shortages on their experience of work stress, the following question was posed: 'How would you describe the impact of skills shortages on your stress levels?' The responses to this question show that 13% (n = 24) indicated that skills shortages did have an impact on their stress levels, 51% (n = 97) indicated that they were not sure, and 34% (n = 64) indicated that skills shortages did not have an impact on their stress levels. A total of three respondents (2%) did not answer the question. The responses indicate that many (34%) of the artisans and engineers included in the sample held the opinion that skills shortages do not have an impact on their levels of stress, while some (13%) indicated that skills shortages do have an impact on their levels of stress.

From the data collected with the open-ended question regarding the impact of skills shortages on work stress, the following themes emerged: coping mechanisms, work-related characteristics, work-life balance, and the physical work environment. The emerging themes regarding the impact of skills shortages on work stress levels of artisans and engineers included in the sample can be divided into individual, extra-organizational, and organizational factors. On an individual level, it seems that some of the respondents struggle to cope with the work stress they are exposed to. Regarding extra-organizational factors, the theme of work-life balance emerged. From the responses, it is clear that some of the respondents are experiencing work stress and non-work-related stress. Organizational factors included the themes of job-related characteristics and the physical work environment. Most of the responses listed under job-related characteristics made reference to work overload. The themes that emerged support previous research findings reported for a South African sample, which indicate that work load issues are the greatest cause of stress, followed by people or relationship issues, and then work-life balance (Nelson, as cited in Coetzee and de Villiers, 2010).

Discussion of results

As is evident from the results presented in Figure 1, the physical work environment had a positive and statistically significant influence on the experience of work stress. This finding is unexpected, and it contradicts previous research findings which indicate that the physical work environment of the mining industry is the main cause of work stress (e.g. Schutte, Edwards, and Milanzi, 2012). The physical work environment subsection of the questionnaire measured specifically the availability of job equipment, such as stationery, tools, and electronic and laboratory equipment, and their working order, as well as being allowed to function in inadequate physical working conditions (e.g. inadequate lighting, temperature, and office space). Thus, the more positively these aspects were evaluated, the more work stress the respondents reported. However, the reality is that employees in the mining industry are exposed to harsh working conditions, long working hours, sometimes unsafe working conditions, highly unionized environments, and enormous pressure to perform (Brand-Labuschagne et al., 2012). Furthermore, mine workers in general are exposed to various safety hazards, such as falling rocks, dust, intense noise, fumes, and high temperatures (Badenhorst, 2006). It is possible that these industry-specific issues were not covered by the items in the questionnaire. It is also possible that the respondents did not perceive their physical work environment as a cause of stress, although it can potentially be the main cause of work stress. Furthermore, as was indicated previously, potential stress will become actual stress only if the outcome is both uncertain and important (Robbins et al., 2009). Therefore, it is possible that the respondents did not perceive the physical work environment as important, and also, their familiarity with this environment may reduce their uncertainty in this regard.

HR policy, especially pertaining to remuneration and fringe benefits, was negatively and statistically significantly related to the experience of work stress. This finding is supported by the argument offered by van der Walt et al. (2016), who state that in occupational categories where skills shortages exist, employees are likely to do more work but are not necessarily being remunerated or rewarded for the additional work they perform. The latter authors further suggest that mining companies should mindfully and continuously consider the structuring of remuneration packages and HR policy pertaining to occupational health and safety, in order to improve the job satisfaction levels of employees affected by skills shortages.

The findings of the study further revealed that job-related tasks were negatively and statistically significantly related to the experience of work stress. Consistent with the findings of the current study, Robbins (2005) asserts that employees prefer jobs that afford them the opportunity to apply their skills and abilities, that offer them variety and freedom, and that provide them with constant feedback on their performance. Furthermore, employees who find their work interesting are likely to be more satisfied and motivated than employees who do not enjoy their jobs. Ongori and Agolla (2008) came to a similar conclusion, and identified the following job-related causes of work-related stress: work overload, time pressure, role ambiguity, long working hours, and shift work. Supporting this finding, some respondents mentioned in their response to the open-ended question that work overload is a cause for concern. It is possible that due to the shortage of employees in the artisan and engineer categories, incumbents may feel that they are given too many tasks, which may leave them feeling that they are not in control of their work and that they cannot meet strict production deadlines. The finding that task characteristics influence work-related stress is of paramount importance to mining companies, and therefore they need to consider whether employees affected by skills shortages are overloaded, whether employees are fairly rewarded for executing additional responsibilities, whether proper instructions are given, and whether reasonable deadlines are set. It is further necessary that appropriate HR policies are developed and continuously updated in order to ensure equity and mental health. By considering these aspects, mining companies can prevent artisans and engineers from being 'poached' by international mining companies, thereby exacerbating the current skills shortages in these occupational categories.

Conclusion

Despite the theoretical and practical contribution of the study, it was not without limitations. Firstly, the study was limited to mining engineers and artisans employed on two gold mines in South Africa. Although the ideal would have been to include a random sample of artisans and engineers working in the South African mining industry, this was not possible due to the wide geographical distribution of mines in the country. This implies that the findings of the current study cannot be generalized to other populations, provinces, and countries. Furthermore, the fact that the study is restricted to the mining industry means that the findings are not generalizable to employees in other occupations and industries where skills shortages are experienced, due to prevailing dissimilar conditions which could yield different findings from those of this study. However, the findings of the study can be used by mining companies to retain artisans and engineers in their employment, rather than promoting the exodus of these employees employed in core occupational categories. Also, although the engineers included in the study were representative of the target population, the number was not sufficient to make meaningful comparisons possible between artisans and engineers.

It is recommended that empirical studies continue to investigate the impact of skills shortages on work behaviour. By understanding the behaviour and experiences of employees affected by skills shortages, mining companies will be in a position to improve the mental health of their workers, which will hold many positive outcomes for this industry. It is further recommended that the study of work stress be extended to include a more representative sample of South Africa's mining industry, in particular people from different occupational groups affected by skills shortages. Thus, it will be interesting to see how the findings of the current sample compare with those of a national and/or international sample. Further research on work stress in South Africa's mining industry should be encouraged. Due to the unique nature of this industry, it seems important that work stress is investigated further, to inform organizational leaders and wellness workers when they create new initiatives. In addition, stress management programmes can be tailored to meet the needs of different occupational groups, focusing on different life skills and coping techniques.

The findings of the current study show that mining companies need to consider interventions to reduce work-related stress, thus ensuring the wellbeing of engineers and artisans. It is proposed that mining companies should place increased emphasis on stress management training and counselling programmes, and that they should improve stress awareness programmes. Furthermore, by developing managerial capacity through effective leadership training programmes, organizational leaders will become more knowledgeable about work-related stressors and employee wellbeing. It is also proposed that artisans and engineers should be provided with work that is carefully structured. This will enhance their autonomy and responsibility, enabling them to utilize their skills. In addition, appropriate recognition should be given to artisans and engineers for their inputs.

The findings of the current study deepen the understanding of work-related stress of employees in occupational categories where skills shortages are experienced. In addition, the findings indicate that it is important for mining companies to consider human resource interventions to reduce work stress, thus ensuring the wellbeing of engineers and artisans in the mining industry. Should mining companies decide to ignore work-related stressors that employees are exposed to, particularly those employed in occupational categories where skills shortages are experienced, skills shortages may worsen, which may be detrimental to the future of the South African mining industry.

References

Badenhorst, C.J. 2006. Occupational health risk assessment: Overview, model and guide for the South African mining industry towards a holistic solution. PhD thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom. [ Links ]

Bennett, J. and McGuinness, S. 2009. Assessing the impact of skill shortages on the productivity performance of high-tech firms in Northern Ireland. Applied Economics, vol. 41, no. 6. pp. 727-737. [ Links ]

Bickford, M. 2005. Stress in the workplace: A general overview of the causes, the effects, and the solutions. Canadian Mental Health Association, Newfoundland and Labrador Division. [ Links ]

Brand-Labüschagne, I., Mustert, K., Rothmann, S., Jr., and Rothmann, J.C. 2012. Burnout and work engagement of South African blue-collar workers: The development of a new scale. Southern African Business Review, vol. 16, no. 1. pp. 58-93. [ Links ]

Carmichael, F., Fenton, S.-J.H., Pinilla-Roncancio, M.V., Sing, M., and Sadhra, S. 2016. Workplace health and wellbeing in construction and retail: Sector specific issues and barriers to resolving them. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, vol. 9, no. 2. pp. 251-268. doi: 10.1108/IJWHM-08-2015-0053 [ Links ]

Chamber of Mines of South Africa. 2013. Annual Report 2012/2013. https://commondatastorage.googleapis.com/comsa/annual-report-2012-2013.pdf [accessed 9 April 2018]. [ Links ]

Coetzee, M. and de villiers, M. 2010. Sources of job stress, work engagement and career orientations of employees in a South African financial institution. Southern African Business Review, vol. 14, no. 1. pp. 27-58. [ Links ]

Considine, R., Tynan, R., James, C., Wiggers, J., Lewin, T., Inder, K., Perkins, D., Handley, T., and Kelly, B. 2017. The contribution of individual, social and work characteristics to employee mental health in a coal mining industry population. PLoS ONE, vol. 12, no. 1. e0168445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168445 [ Links ]

Coopmans, J.W.M. 2007. Stress related causes of presenteeism amongst South African managers. MBA dissertation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Daniels, R.C. 2007. Skills shortages in South Africa: A literature review. Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Del Fabbro, G. 2012. High degrees of stress threaten workplace productivity. http://www.skillsportal.co.za/page/human-resource/1440174-High-degrees-of-stress-threaten-workplace-productivity [accessed 30 June 2013]. [ Links ]

Erasmus, J. and Breier, M. (eds). 2009. Skills shortages in South Africa: Case studies of key professions. Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Gibbens, N. 2007. Levels and causes of stress amongst nurses in private hospitals: Gauteng Province. MSocSc dissertation, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

Griffin, R.W. and Moorhead, G. 2012. Organizational Behavior: Managing People and Organizations. 10th edn. South-Western Cengage Learning, Mason, OH. [ Links ]

Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E., and Tatham, R.L. 2006. Multivariate Data Analysis. 6th edn. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. [ Links ]

Hair, J.F., Ringle, CM., and Sarstedt, M. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, vol. 19, no. 2. pp.139-152. [ Links ]

Hasnain, N., Naz, I., and Bano, S. 2010. Stress and well-being of lawyers. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, vol. 36, no. 1. pp. 165-168. [ Links ]

John, D. 2006. The impact of skills shortages on client satisfaction at Stewart Scott International in KwaZulu-Natal. MBA dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Khalane, S. 2011. Nationalisation will worsen brain drain. Free State Times, June. pp. 24-30. [ Links ]

Lüthans, F. 2002. Organizational Behavior. 9th edn. McGraw-Hill Irwin, Boston. [ Links ]

Luthans, F. 2011. Organizational Behavior: An Evidence-Based Approach. 12th edn. McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York. [ Links ]

Masia, U. and Pienaar, J. 2011. Unravelling safety compliance in the mining industry: Examining the role of work stress, job insecurity, satisfaction and commitment as antecedents. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, vol. 37, no. 1. pp. 1-10. [ Links ]

Negi, K.R. 2014. Study of work stress in employees of business organizations of Matsasya Industrial Area, Alwar District, Rajasthan. International Journal of Management and International Business Studies, vol. 4, no. 2. pp. 169-174. [ Links ]

Oberholzer, C. 2010. South Africa has critical shortage of mining skills. www.solidaritysa.co.za/Home/wmprint.php?ArtID=2377 [accessed 12 January 2012]. [ Links ]

OgiNska-Bulik, N. 2005. Emotional intelligence in the workplace: Exploring its effects on occupational stress and health outcomes in human service workers. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, vol. 18, no. 2. pp. 167-175. [ Links ]

Ongori, H. and Agolla, J.E. 2008. Occupational stress in organizations and its effects on organizational performance. Journal of Management Resources, vol. 8, no. 3. pp. 123-135. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, J.D. and van Lill, B. 2008. Coping with stress in the workplace. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, vol. 34, no. 1. pp. 64-69. [ Links ]

Paten, N. 2006. Construction workers stressed. Occupational Health, vol. 58, no. 5. p. 8. [ Links ]

Quick, J.C. and Nelson, D.I. 2009. Principles of Organizational Behavior: Realities and Challenges. 7th edn. South-Western Cengage Learning, Florence, KY. [ Links ]

Razzak, W.A. and Timmins, J.C. 2008. A macroeconomic perspective on skill shortages and the skill premium in New Zealand. Australian Economic Papers, vol. 47, no. 1. pp. 74-91. [ Links ]

Robbins, S.P. 2005. Essentials of Organizational Behavior. 8th edn. Pearson/Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. [ Links ]

Robbins, S., Judge, T.A., Odendaal, A., and Roodt, G. 2009. Organisational Behaviour: Global and Southern African Perspectives. 2nd edn. Pearson Education, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Schaap, P. and Kekana, E. 2016. The structural validity of the Experience of Work and Life Circumstances Questionnaire (WLQ). South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, vol. 42, no. 1. a1349. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v42i1.1349 [ Links ]

Schütte, P.C., Edwards, A., and Milanzi, I.A. 2012. How hard do mineworkers work? An assessment of workplace stress associated with routine mining activities. Proceedings of the Mine Ventilation Society of South Africa Conference, Emperors Palace, Kempton Park, 28-30 March 2012. http://researchspace.csir.co.za/dspace/bitstream/handle/10204/5855/Schutte_2012.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [accessed 6 March 2019]. [ Links ]

Sebusi, I.e. 2007. An economic analysis of the skills shortage problem in South Africa. MCom dissertation, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Smit, N.W.H., De Beer, LT., and Pienaar, J. 2016. Work stressors, job insecurity, union support, job satisfaction and safety outcomes within the iron ore mining environment. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 14, no. 1. a719. [ Links ]

South Africa. Department of Labour (DoL). 2006. National Skills Development Strategy: Implementation Report, 1 April 2004 - 31 March 2005. Department of Labour, Pretoria. [ Links ]

South Africa. Mining Qualifications Authority. 2008. A guide for identifying and addressing scarce and critical skills in the mining and minerals sector. http://mqa.org.za/sites/default/files/MQA%20Scarce%20Skills%20Guide.pdf [Accessed 30 November 2009]. [ Links ]

South Africa. 2017. Health Professions Act, Act 56 of 1974, Notice 155 of 2017. Government Printer, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Toni, T. 2009. Causes and consequences of the shortage of electrical artisans at Eskom. MBA dissertation, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth. [ Links ]

Van der Walt, F., Thasi, M.E., Jonck, P., and Chipunza, C. 2016. Skills shortages and job satisfaction - insights from the gold-mining sector of South Africa. African Journal of Business and Economic Research, vol. 11, no. 1. pp. 141-181. [ Links ]

Van Zyl, E.S. and van der Walt, H.S. 1991. Manual for the Experience of Work and Life Circumstances Questionnaire (WLQ). Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Velnampy, T. and Aravinthan, S.A. 2013. Occupational stress and organizational commitment in private banks: A Sri Lankan experience. European Journal of Business and Management, vol. 5, no. 7. pp. 243-267. [ Links ]

Welman, J.C., Krüger, S.J., and Mitchell, B. 2005. Research Methodology. 4th edn. Oxford University Press, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Wickham, J. and Bruff, I. 2008. Skills shortages are not always what they seem: Migration and the Irish software industry. New Technology, Work and Employment, vol. 23 no. 1-2. pp. 30-43. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

F. Van Der Walt

fvdwalt@cut.ac.za

Received: 13 Mar. 2019

Revised: 15 Oct. 2019

Accepted: 21 Nov. 2019

Published: March 2020