Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717

Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.116 n.6 Johannesburg Jun. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/2016/v116n6a1

PAPERS - COOPER COBALT AFRICA CONFERENCE

Copper mining in Zambia - history and future

J. SikamoI, II; A. MwanzaI; C. MweembaI

IZambia Chamber of Mines

IIChibuluma Mines Plc, Zambia

SYNOPSIS

The Zambian copper mining industry as we know it today had its genesis in the 1920s. Consistent private sector-driven investment in the industry over a period of over 50 years in exploration, mine development and operation, development of minerals processing facilities, building of infrastructure for pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processing, with attendant support facilities, including building of whole new towns, resulted in copper production rising to a peak of 769 000 t in 1969, providingover 62 000 direct jobs. The industry was nationalized in 1973 and remained in government hands for just over 24 years. During this period, the industry experienced a serious decline in production levels, reaching the lowest level in the year 2000 when production was 250 000 t. An average of just under 2000 jobs were lost every year in the 24-year period, reaching just over 22 000 direct jobs in 2000.

Following the return of Zambian politics to pluralism and liberalized economic policies, the government decided to privatize the mining industry. The process started in 1996 and by the year 2000 all the mining assets had been privatized. The new investors embarked on serious investment to upgrade the assets and to develop greenfield mining projects. Fourteen years later and after more than US$12 billion investment, production levels increased year-on-year to a peak of 763 000 t in 2013 with direct jobs reaching 90 000.

This paper discusses the impact of the mining industry in Zambia on the economy in areas such as employment, support for other industries, direct contribution to the national gross domestic product (GDP), foreign exchange earnings, and social amenities. The paper also focuses on the performance of the mines during these periods vis-à-vis mineral availability, mineral grades and complexity, new technologies, and human capital. This is looked at particularly in the light of current challenges the industry is facing. Suggestions are proposed on how the industry can be nurtured to continue being a major driver for the Zambian economy and a major player in the international copper mining business.

Keywords: copper mining, Zambia, history, nationalization, privatization, production, national economy

Introduction

Mining had been going on in the region known today as Zambia long before the white settlers came on the scene. The mining was of a traditional and subsistence nature and confined to surface outcrop deposits. The natives of Zambia would melt and mould the copper into ingots used as a medium of exchange and other metal products, such as hand tools and weapons.

Although on a small scale, the mining activities by the natives were wide spread across the Copperbelt region and other places. In fact, most of the deposits discovered by the settlers were found with the assistance of local scouts, who had knowledge of the whereabouts of the copper minerals. The Chibuluma mine deposits are the only ones in Zambia known to have been discovered without information passed on from the local people.

It was the presence of copper in Zambia which led to the region being put under British indirect rule in 1889 (About.com, 2015) after the partition of Africa. The years following 1889 saw extensive exploration activities in the region by western companies and individuals. Exploration activities led to the first commercial copper being produced at Kansanshi, Solwezi, in 1908 (Roan Consolidated Copper Mines, 1978). Later, prospectors obtained concessions from the British South African Company (BSA) which had obtained mining rights in the area from King Lewanika of the Lozi in 1900 (About.com, 2015). As more copper deposits were found, Zambia was put under direct British rule as a protectorate under the Colonial Office in 1924.

Post-1924 saw the beginning of massive investments in mine developments, led mainly by American and South African companies. As a result, there was an influx of white settlers into the area as well as natives who migrated from their villages to provide labour on the mines. Table I shows the increase in the white population during this period.

Population increase lead to the establishment of settlements which rapidly grew into new towns. Support industries emerged and infrastructure such as hospitals, schools, roads, markets, and recreational facilities were built. Thus, by 1964, when Zambia was born, it had a strong economy driven by the mining sector.

From the beginning to nationalization (1928-1973)

Although copper had been produced at Kansanshi and Bwana Mkubwa in 1908 and 1911, respectively, the first commercial mine in Zambia was established in Luanshya in 1928 (Roan Consolidated Copper Mines, 1978). Opening of other mines followed, as shown in Table II.

The owners of these mines were driven by the high demand and favourable prices of copper and the need to maximize their profits. Flotation technology for separating copper sulphide minerals from ores had been commercialized and this advance enabled large quantities of copper to be produced. The mine owners therefore invested in concentrators, smelters, and other metal extraction facilities, a situation which continued until 1969.

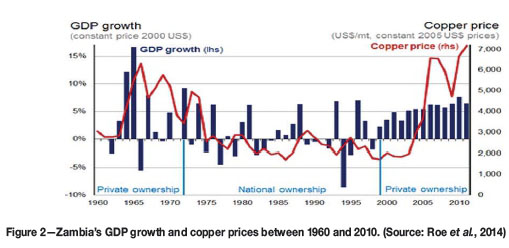

By 1964, Zambia was a major player in the world copper industry, contributing over 12% of global output (Sikamo, 2015). The economy grew to an extent where, in 1969, the nation was classified a middle-income country (Sardanis, 2014a) and had one of the highest gross domestic products (GDPs) in Africa, higher than Ghana, Kenya (see Figure 1), and South Korea, whose per capita income in 1965 was US$106 compared with Zambia's US$294 (SARPN, 2015). The mining sector continued providing direct and indirect employment, such that, by 1972, 62 000 people were directly employed by the mines (Sikamo, 2015). Growth in the economy also led other sectors of the economy to grow, such as transport, construction, manufacturing, and trading. The national GDP growth was above 5% between 1964 and 1970 (Figure 2).

However, the period 1964 to 1969 saw reduced investments in the mining industry, due to the issue of royalties between the government and the mine owners. Mineral royalties in Zambia were held by the BSA Company from inception to 1964, when the country achieved independence (Roan Consolidated Copper Mines, 1978). After 1964, the mineral rights went to the government without changing the taxation structure. However, the cost became real for the owners since they were shareholders of BSA Company and never used to view the royalties paid to BSA as a real cost. As such, their arguments to have the mineral royalty tax reduced were denied by the Zambian government.

During this period (1964-1969), the government was not happy with the level of participation of the indigenous population in the national economy in general and the mining sector in particular. A number of reforms were embarked upon. The Mulungushi reforms in 1968 gave 51% ownership in major industries to the Zambian government, managed under the parastatal Industrial Development Corporation (INDECO). In 1969, the Matero reforms were announced, which gave the government 51% ownership of the mines, managed under Mining Development Corporation (MINDECO). Thus began the era of mining nationalization, which was completely effected by 1973 (Sardanis, 2014b; SARPN, 2015).

Nationalization of the mines (1973-1996/2000)

Nationalization of the Zambian mines began with the Matero declaration of 1969, when the government obtained a 51% shareholding in the then two existing mining companies. These were Roan Selection Trust and Anglo American Corporation, which owned all the operating mines in the country between them. Prior to the Matero declarations, the government had issued the Mulungushi declarations, under which 51% of the shares in all the major industries (except mines) were put in state hands. This led to the formation of INDECO as the holding company for these shares. The Matero reforms resulted in the formation of a holding company for the mines' shares to be called MINDECO. An umbrella company for MINDECO and INDECO was formed and was called Zambia Industrial and Mining Corporation (ZIMCO). Roan Selection Trust became Roan Consolidated Copper Mines (RCM), comprising Mufurila, Luanshya, Chibuluma, Chambishi, Kalengwa, and Ndola Copper Refinery. The Zambian arm of Anglo American Corporation became Nchanga Consolidated Copper Mines (NCCM) and was in charge of Rhokana, Nchanga, and Konkola mines.

The Matero reforms were implemented in January 1970 and the government was to pay for those shares over a period of roughly 10 years (SARPN, 2015). However, in 1973, the government decided to redeem all the outstanding bonds and made the following changes in the management structure. MINDECO was no longer in charge of RCM and NCCM, but other small mines in the country. INDECO, MINDECO, RCM, and NCCM all fell under the management of an overarching parastatal Zambia Industrial and Mining Corporation (ZIMCO). All the managing directors of RCM and NCCM as well as the chairman of ZIMCO were political appointees. The Minister of Mines was the chairman of RCM, NCCM, and ZIMCO. In the same year, the country changed its constitution and became a one-party state.

The government started using the revenues from the mining sector to advance the national developmental agenda. Massive projects were embarked upon, such as the Kafue and Itezhi Tezhi hydropower stations, the TAZARA rail line, housing projects, schools, hospitals, and road infrastructure.

The education sector is one area that received massive investments from the mines during this period. Both the mines and the country benefited both in the short and long term. Prior to nationalization, private owners did very little to advance the knowledge base of the indigenous population- all measures were meant to benefit the settlers and their children. However, after nationalization, there was a deliberate policy by government through the mines to educate the children of Zambians. High-standard schools were built where excelling children of miners and sometimes non-miners were enrolled. These students were later sent to top universities all around the world to train, mainly in mining disciplines. Artisan training colleges were also set up for miners and school leavers who were to be employed by the mines. Gradually, the gap left by the white settlers in areas of skilled manpower was greatly reduced. The mining skill level of Zambia improved so much that later, when the mines were re-privatized, the new owners did not need to employ many expatriates. In some cases, Zambian mining professionals were appointed as chief executive officers (CEOs) of foreign mining companies after re-privatization.

Meanwhile, there was no letting up on the government's stranglehold on the mines. In 1982, the government merged RCM and NCCM into one entity called Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM), which continued financing national programmes at the expense of its own operations. This financial burden on ZCCM took its toll. The mines suffered undercapitalization and could not replace worn and obsolete machinery. There was little investment in technological upgrades, despite the increasing difficulties in mining and processing as mining proceeded deeper and the mineral grades leaner and more complex. Inevitably, production output declined while production costs were soaring. Employment levels reduced as the mines downsized their labour forces. The price of copper remained low while that of oil was skyrocketing. The business prospects of the mines were bleak, and so were those for the national economy, which was heavily reliant on mining.

Shortage of consumer commodities in shops became the order of the day and political agitation for the end of one-party rule started. In 1990, the country reverted to multiparty politics and a new government, which promised to privatize the mines, was voted into office in 1991.

Re-privatization

Although the new government, which had promised privatization of the mines, was in place by 1991, the privatization exercise started only in 1996 and was not completed until 2000. Critics had mixed views on the pace of the re-privatization process, but, with hindsight, one cannot help but think that it should have been faster. This is because the decline in copper production continued in this period, exacerbated by job uncertainties, as mines continued the exercise of labour reduction. The national economy was not doing any better, although the effects were being mitigated by donor financing in a spirit of goodwill to the new government.

When re-privatization started, the government decided to unbundle ZCCM into smaller units. Smaller mines were the first to be put into private hands. However, privatization can be said to have happened only when the two big units, Konkola Copper Mines (KCM), which comprised Nchanga, Konkola, Nampundwe and part of Nkana assets, and Mopani Copper Mines, which comprised assets at Nkana and Mufulira, were privatized in 2000. Mopani Copper Mines was sold to Glencore as the major shareholder, while KCM was offered to Anglo American Corporation (AAC). In 2002, AAC returned the mines to the government, which offered them to Vedanta of India in 2004.

The new mine owners invested massively in the mines and there was a sudden economic upturn, not only on the Copperbelt but in the country as a whole, with the mining industry as a pivotal contributor. Investments went into new machinery, new mining methods, and new mineral processing and metal extraction technologies. There were also massive greenfield projects at Kansanshi and Lumwana, both in the North West Province of Zambia, which brought newer technologies into the industry. These mines were able to process large quantities of low-grade copper ores at very low cost.

Copper production reached a peak of 720 000 t in 1969, the same year that the nationalization discussions picked up speed. By the time nationalization was being completed in 1973, production had dropped slightly to 700 000 t. This resulted from the fact that immediately the nationalization discussions started, investment in the mining industry started falling. After nationalization, production continued to drop and, in the subsequent 24 years of nationalization, production dropped to 250 000 t by the year 2000. Following the massive investment of the new mine owners in refurbishing the mines, which had not been seeing any investment, and investment in greenfield projects (see Table III), production levels began to increase. By 2013, production had reached 763 000 t (see Figure 3) and the industry had over 90 000 direct employees from the low of 22 000 at the time that privatization was completed. It is worth noting that the amount of copper produced per person in 2013 is lower than in 1972 due to the fact that, before re-privatization, mines were jointly owned and overhead services were shared. Furthermore, the copper grades were higher, which increased unit labour productivity.

Contribution of the mining industry to the Zambian economy

Although it is the desire of the Zambian government to diversify the economy, the Zambian copper mining industry will remain the engine that will drive this diversification for a long time to come. In the work done by International Council on Metals and Mining (ICMM), verified data from 2012 statistics shows that, in that year, 86% of the foreign direct investment that came into Zambia was due to the mining industry, 80% of the country's export earnings came from the mining industry, as well as over 25% of all revenues collected by government. The mining industry contributed more than 10% to the GDP, and more than 1.7% of all formal employment in the country (see Figure 4). These parameters show that Zambia's reliance on the mining industry is way above that of other countries that are similar to Zambia in terms of their dependence on the extractive industries.

The same ICMM study looked in more detail at the contribution to government revenue in terms of all taxes paid, as shown in Figure 5. It is clear that, during the period 1995 to 2000, taxes paid by the mines constituted around 1% to 2% of all taxes. As investments began to mature and improvements put in place began to bear fruit, all the taxes paid began to show an upward trend-to the extent that, by 2011, taxes collected from the mines averaged 35% of the total taxes. This trend shows that increasing revenues to government can be guaranteed by increasing production and a favourable price. This is clearly seen in Figure 6, by the doubling of revenue collection between 2010 and 2011 without a change in tax regime.

In terms of revenue collection, Zambia joined the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) as a candidate in May 2009 and was fully compliant in September 2012 (Moore Stephens, 2013, 2014). EITI is an international organization that promotes transparency in the declaration of earnings and revenues arising from the extractive industries. In Zambia, the local organization is called Zambia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (ZEITI) and it monitors what the mining companies say they have paid into government and government agencies and what government acknowledges as having received. The overall objectives of the reconciliation exercise are to assist the government of Zambia in identifying the positive contribution that mineral resources are making to the economic and social development of the country, and to realize their potential through improved resource governance that encompasses and fully implements the principles and criteria of the EITI. ZEITI has so far released six reports for 2008 to 2013. These reports show remarkable agreement between what government acknowledges as having received and what the mining companies say they have paid. From the reports, and as summarized in Figure 6, it is clear that the mining industry has been contributing revenues to the treasury on an increasing basis in line with increasing production and copper price fluctuations (Moore Stephens, 2013, 2014). For comparison with international currencies, refer to Figure 7, which shows the Zambian kwacha (ZWK) exchange rate against the US dollar in the period 2008-2013, which averages between ZWK 4 and ZWK 5 to US$1.

Conclusion - the future of mining in Zambia

The geology of Zambia shows great potential for further investment in mining. The past few years have seen significant instability in the fiscal regime and this has undermined new investment into the sector. The challenges of the 2013 to 2014 fiscal regime resulted in copper production dropping from 763 000 t in 2013 to 708 000 t in 2014. The first half of 2015 saw a further decline in production, particularly following the uncertainty brought about by the Mineral Royalty Taxation regime of 2015. It is gratifying to see that the government has shown serious desire to engage in dialogue to arrive at optimum levels of taxation which will ensure that government continues to receive taxes from the mines, and also that the mines continue to thrive and invest, on a sustainable basis. Clearly this is the way to go. This state of affairs has been confirmed by government, which has said that it is committed to putting in place a taxation regime that is stable, predictable, consistent, and transparent. Investors have welcomed this and obviously this should translate into a very bright future for the Zambian mining industry.

The mines performed badly during the period of nationalization, since they lost focus from their core business. Continuous re-investment in machinery and new technology is very important for increasing productivity. Investing in human capital is another area that is very important and new mine owners will do well not to neglect this aspect. It is gratifying to see that the mining companies operating in Zambia are taking all these important aspects of mine development into consideration, and the results are visible.

For its part, government should continue providing policies that will attract capital into the mining industry. These policies should be dynamic in nature so that the country remains competitive with other major players on the global market. The key here is continuous engagement with stake holders so that the government is abreast of the changing challenges and other requirements in the industry. To counter the legacy of prolonged undercapitalization of the old mines, particularly regarding modern machinery and technology, government should encourage greenfield projects that are able to build low-cost mining operations that can withstand the constant shock of copper price fluctuations.

References

About.com. 2015. African history. http://www.africanhistory.about.com/od/zambia/ l/Bl-Zambia-Timeline.htm [ Links ]

Moore Stephens. 2013. Zambia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. Fifth reconciliation report based on the financial year 2012. [ Links ]

Moore Stephens. 2014. Zambia Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. Sixth reconciliation report based on the financial year 2013. https://eiti.org/files/zeiti_2013_reconciliation_ final_report_18_12_14%20%281%29%20%282%29.pdf [ Links ]

Roan Consolidated Copper Mines. 1978. Zambia's Mining Industry: the First 50 Years. (Privately published). [ Links ]

Roe, A., Dodd, S., Ostensson, O., Henstridge, M., Jakobsen, M., Haglund, D., Dietsche, E., and Slaven, C. 2014. Mining in Zambia-ICMM Mining partnerships for Development. Toolkit Implementation. International Council on Mining and Metals. http://www.icmm.com/document/7066 [ Links ]

Southern African Regional Poverty Network (SARPN). 2015. www.sarpn.org/documents/d0002403/3-Zambia_copper-mines_Lungu. [ Links ]

Sikamo, J. 2015. Presentation on the state of the Zambian Mining Industry. Zambia Chamber of Mines, Lusaka. [ Links ]

Sardanis, A. 2014a. Zambia: the First 50 Years. I.B. Tauris. [ Links ]

Sardanis, A. 2014b. Africa: Another Side of the Coin. Northern Rhodesia's Final Years and Zambia's Nationhood. I.B. Tauris. [ Links ]

This paper was first presented at the, Copper Cobalt Africa Conference, 6-8 July 2015, Avani Victoria Falls Hotel, Victoria Falls, Livingstone, Zambia.