Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717

Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.115 n.6 Johannesburg Jun. 2015

PLATINUM CONFERENCE PAPERS

Tough choices facing the South African mining industry

A. LaneI; J. GuzekII; W. van AntwerpenII

IMonitor Deloitte

IIDeloitte Consulting

SYNOPSIS

Strategy is about making choices. Mining companies choose to do certain things and not to do other things. Mining is a long-term business, and the choices made typically have large investments attached to them, long payback periods, and significant socio-economic consequences. In today's uncertain world, it is important to make the right choices. The mining industry in South Africa finds itself in a difficult situation. Operating conditions are tough, the socio-political environment is complex, and financial performance is under pressure. The choices made by all the stakeholders in this industry in the short term will shape the future of the industry. This paper characterizes some of the big, difficult decisions faced by the mining industry in the South African context, and discusses how these decisions could be approached in a fact-based and robust way.

Keywords: Strategy, choices, community, social impact, scenarios, portfolio optimization, adaptive cost management, stakeholders, innovation

Introduction

Mining companies in South Africa face significant challenges, putting the industry at a crossroads. Local mining companies manage unique South African operational complexities while still operating in the context of global pressures. Monitor Deloitte has identified five tough choices that mining executives must face to ensure long-term sustainability. The answers to these questions are not obvious, and require an analytical approach. This paper proposes five tools that can assist mining executives in understanding the issues underlying these questions, and how mining companies can develop integrative strategies to drive sustainable growth.

The current mining situation

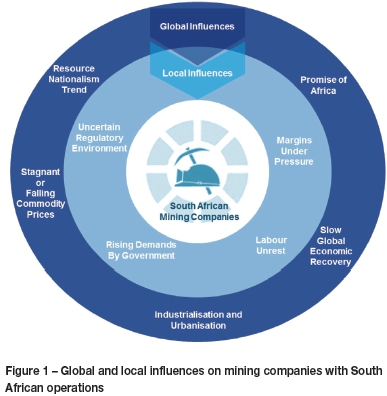

Globally, mining companies are facing a series of economic, financial, and operational challenges. South African mining companies! must also account for uniquely local issues with profound operational implications. Some of the pressing issues are shown in Figure 1.

The global situation

Mining companies are inevitably influenced by global developments, with macro-economic growth and international markets strongly influencing both the demand for resources and profitability.

Historically, there has been a strong correlation between the performance of commodity markets and mining stocks; however, this relationship appears to have broken down. Mining stocks (including those of global diversified mining players such as BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto) continue to underperform broad commodity price benchmarks. This gap between stock performance and commodity indices may be due to investors attaching a higher risk premium to mining stocks owing to a poor track record of project delivery and a lack of new discoveries, resulting in sub-optimal shareholder returns.

Globally important economies such as the USA, Europe, and China are slowly recovering from the recession; however, there are mixed signals for future growth. While the USA, the world's largest economy, has been recovering slowly, Europe continues to face a sovereign debt crisis. In response to this, the European Union has undertaken deep structural reforms, including various financial support mechanisms (such as bailouts and austerity programmes) for countries with troubled economies. While this may have temporarily appeased markets, the memory of the Eurozone crisis is likely to remain fresh in investors' minds in years to come. With limited post-recession growth prospects in the USA and Europe, companies have looked to Asia to drive global demand. China's expected growth rate of 8.4% in 2013 (Deloitte Market Intelligence, 2013) falls short of its pre-recession growth rate, which averaged 10.3% between 1999 and 2009 (McNitt, 2013); however, the year-on-year increase from 7.5% in 2012 is positive news for mining that rely on China's continued appetite for resources. While the global economic outlook for these key economies remains constrained, the ongoing trend towards industrialization and urbanization is likely to sustain long-term demand for resources.

In addition to the current decline in demand, mining companies face further challenges to profitability in the form of unfavourable commodity prices and tougher mining conditions. While commodity prices have improved since their 2008 lows, prices remain stagnant or falling, limiting revenue potential. Declining ore grades at current depths also mean that mining companies have to mine deeper to reach new deposits, significantly increasing the cost of extraction. Since the start of 2000, over 75% of new base metal discoveries have been at depths greater than 300 m (Deloitte Market Intelligence, 2013). Mining at these depths also introduces additional safety issues due to the high risk of rockfalls, flooding, gas discharges, seismic events, and ventilation problems.

Compounding these economic and operational factors, mining companies also face regulatory uncertainty following a global trend of resource nationalism. Governments throughout the world are looking to increase their share of mining profits as a means to bolster slow economies and drive socio-economic development. State interventions in the mining industry vary from the introduction of new resource-based taxes to transferring of mining rights to state-owned companies, as shown in Figure 2. This regulatory uncertainty poses a significant challenge to mining companies' long-term strategic planning.

Despite the particularly uncertain regulatory environment in Africa, global mining companies cannot ignore the substantial growth prospects that the continent offers. Africa has vast mineral riches, with significant reserves of more than 60 metals and mineral products, estimated at 30% of the world's entire mineral reserves (Deloitte Mining Intelligence, 2013). Despite this resource base, Africa's production represents only 8% of global mineral production, and is mostly exported in raw form. The relatively low exploration spend (at US$5 per square kilometre across Africa compared with US$65 per square kilometre in Canada, Australia, and Latin America) (McNitt, 2013) further highlights the opportunity for mining companies to take advantage of this new frontier for expansion, especially for those companies looking to expand into emerging markets.

Mining companies looking to operate on the African continent face unique challenges. While most companies benefit from long-term certainty and predictability, these market characteristics are even more important to long-term businesses like mining. Mining companies require a degree of political stability, investment-friendliness, appropriate transportation infrastructure, and balanced fiscal regimes to operate successfully. There are several issues prevalent across the African continent that run counter to these requirements, and which contribute to the perception of Africa as a risky destination for business. Poor governance, the prevalence or perception of corruption, tenuous legislative frameworks, fragile security of tenure, and unclear royalty and tax regimes make strategic decisions difficult. Furthermore, long-standing issues such as civil unrest, insurgency, and a history of ethnic conflict pose additional operational risks in certain countries.

Besides socio-economic and political complexities, the lack of appropriate infrastructure across Africa is a further barrier for mining companies. The required infrastructure capital is far more than the current infrastructure spend, leaving a substantial spending shortfall. This development constraint leaves investors with little confidence that public-sector infrastructure development will improve sufficiently to facilitate operations. African governments are turning to mining companies themselves to accelerate infrastructure development, linking mining licence issuance to huge infrastructure projects (McNitt, 2013). These multi-billion dollar foreign investments are likely to have a far greater impact on African infrastructure development than public-sector spending.

The relationship between mining companies and host countries' governments is challenging. Of the 54 countries in Africa, 24 rely on relatively few mineral products to generate more than 75% of their export earnings (Monitor Deloitte analysis). Despite this economic dependence on a prosperous mining industry, host governments habitually treat mining companies with suspicion. Mining operations are viewed as operations in isolation without the necessary linkages and benefits to other sectors of the economy or alignment with local aspirations. Furthermore, the history of colonialism across Africa has often resulted in foreign-owned mining companies being viewed by communities as entities with no long-term commitment to the country. Communities often perceive companies as generating wealth and repatriating dividends, leaving behind a damaged environment with little lasting benefit for the community.

The South African situation

In addition to the complex factors affecting mining companies at a global level, companies with South African operations face further complexities. Mining has historically been a very important sector to the South African economy. Like many other African countries, South Africa has vast mineral wealth with immense value generation potential. With more than 52 commodities under its surface, South Africa has the world's largest reserves of platinum, manganese, chrome, vanadium, and gold, as well as major reserves of coal, iron ore, zirconium, and titanium minerals (Monitor Deloitte analysis). The combined value of these resources is estimated at US$2.5 trillion. The industry's substantial wealth has supported the country's growth with strong resource exports and job creation. However, the mining industry's relative contribution to the economy has declined due to growth in the financial and real estate sectors.

To an even greater extent than their global counterparts, South African mining companies' margins are under pressure. The combination of stagnant or falling global commodity prices and rising input costs is forcing mining companies to make difficult decisions in an attempt to sustain short-term operations, while still aligning these decisions with long-term objectives. In particular, increases in labour and energy costs have exceeded inflation. The annual 'strike season' is characterized by ever-increasing demands by unions and mineworkers who may not have a full appreciation of the challenging operating environment that mining companies face.

In addition to the requirements by workers, there are rising demands by government as to the role mines should play in society. The government increasingly expects mining companies to fulfil social needs typically addressed by government in developed countries, such as the provision of basic services, education, and health care. These expectations are often not clearly defined, and are compounded by local communities' demands for employment opportunities, skills development opportunities, education, and modern healthcare facilities.

'Gone are the days when mining contribution is measured only its contribution to the gross domestic product, or royalties that it pays to the fiscus. Communities expect mining companies to become engines of socio-economic development of their areas' - Susan Shabangu, Minister of Minerals

The perception of a lack of (or inadequate) progress in these key areas is often met with vocal opposition, strikes, and unrest. This can have a significant impact on project development through costly operational delays and reputa-tional damage to mining companies. This puts mining companies in a tenuous position, with corporate social responsibility (CSR) today extending well beyond the minimum legal requirements. South African mining companies require a deep understanding of shifting community and government expectations and a commitment to a high level of transparency and operational sustainability to address the demands of relevant stakeholder groups.

Government's requirements are further obscured by a local environment loaded with rhetoric. Some government officials have criticized the country's inability to translate its mineral wealth into sustainable economic development at grassroots levels. The government has been criticized for being seemingly slow to address what the previous Mineral Resources Minister, Susan Shabangu, called South Africa's 'evil triplets' of poverty, inequality, and unemployment (Sowetan, 2011).

In this highly political context, proponents of radical state intervention in the South African mining industry have asserted that the mineral wealth of the country ends up in the pockets of 'monopoly capital' rather than benefiting the broader population (Monitor Deloitte analysis). While the government has ultimately declared that it has no short-term agenda to pursue resource nationalization, the widely reported rhetoric has cost the country a sharp decrease in its attractiveness as a mining destination, resulting in billions of dollars in deferred or abandoned investments (The National, 2013). This negative local sentiment is likely to have gained additional momentum due to the global trend towards resource nationalism and community activism, especially across the developing world.

The overarching challenge in Africa (and particularly in South Africa) is to strike an equitable balance of interests, ensuring that mining is productive and profitable, as well as being fair to foreign investors, host states, and affected local communities alike. These challenges, at both a local and global level, make strategy critically important for mining companies.

The strategy of decision-making

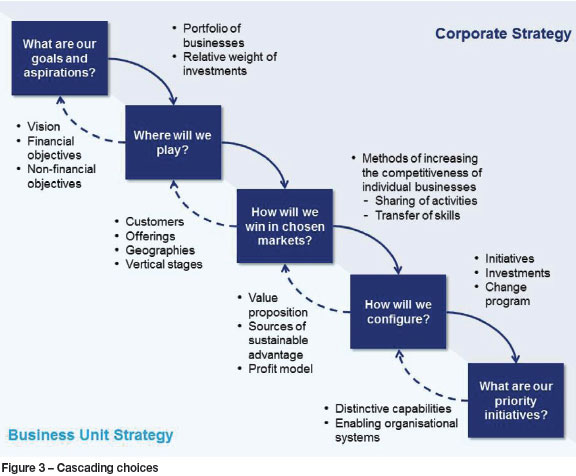

Strategy is about making choices. Companies choose to do certain things and not to do other things (as opposed to tactics, which are about how to execute on the choices made). The complex operating environment in which mining companies function results in difficult choices. This necessitates a deep understanding of the factors that influence mine profitability, as well as those affecting the company's reputation and relationship with stakeholders. Adopting a structured approach to making choices at a corporate and business unit level is essential. Strategy is an integrated set of choices that includes both strategic positioning choices and strategic activation choices.

Monitor Deloitte assists mining companies to make difficult decisions based on a series of cascading choices, as shown in Figure 3. Mining companies should be able to answer each question successively, working down the cascade. Where a question leads executives to re-evaluate their initial propositions, they can trace back up the cascade to redefine aspects until the strategy is cohesive. These questions allow mining companies to successively focus on key aspects of their high-level and operational strategies, which collectively form the basis for long-term strategic planning and short-term prioritization. The questions shown in Figure 3 can be adapted to the mining context as follows.

What are our aspirations?

Mining companies should be able to clearly define both the financial (such as achieving year-on-year increases in average IRR) and non-financial objectives (such as consistently achieving zero harm, or making a positive social impact in host countries). These objectives should be aligned with the company's overall vision, as they will guide investment decisions.

Where will we play?

Mining companies must choose the resource portfolio that they wish to develop and the countries in which they will operate. They must also decide which parts of the value stream they will target, and where in the project life cycle they should enter or exit.

How will we win in chosen markets?

Mining companies should identify sources of sustainable advantage, and use these as the basis for business model development. These choices typically include the mining method, mine design, technology, and sustainability choices. These choices are necessary to achieve the goals and aspirations within the confines of where the company has chosen to play.

How will we configure?

Mining companies should ensure that they have the capabilities and skills in place and that they are configured appropriately to successfully implement these strategies.

What are the priority initiatives?

In a complex global market, mining companies must prioritize key initiatives and investments in order to execute on the choices made.

Using this decision framework, Monitor Deloitte has identified five generic 'tough choices' that face South African mining executives.

Tough choices facing mining companies

Management teams at mining companies with South African operations face a series of tough choices and trade-offs. These are difficult decisions with a broad impact, but ultimately they are critical for long-term survival. Monitor Deloitte has identified five generic questions of particular significance to South African mining companies in light of the global operating context:

➤ How to achieve a step change in profitability and safety performance?

➤ How to attract and retain critical skills?

➤ How to raise the capital needed for South African operations?

➤ What is the best and most sustainable use of capital?

➤ How to balance the conflicting needs of stakeholders? These questions are explored below.

How can mining companies achieve a step change in profitability and safety performance?

South African mining companies must simultaneously defend and grow profits, while also ensuring that safety records improve. While South Africa's mining safety records are steadily improving, mine injury and fatality levels are still above those achieved elsewhere in the world (Business Day, 2013a). With mines becoming progressively deeper and ore grades declining, the unit cost of mine production in South Africa is under significant pressure. The situation is exacerbated by rapidly rising input costs, particularly those of energy and labour.

All of the major South African mining companies have been through successive waves of cost reduction and safety improvement initiatives. While these have often been successful, the rate of incremental improvement has not kept pace with the pressures that are inexorably driving up unit costs. Most mines operating in South Africa are in need of a step change in performance.

How can mining companies attract and retain criticalskills?

Mines continue to face severe frontline and professional skills shortages that affect critical day-to-day operations. Although training programmes have improved, there is still a lack of experienced skills in frontline positions, such as artisans and supervisors, as experienced personnel retire or leave the company. Although current learnerships do produce high volumes of graduates, these graduates often lack necessary hands-on experience. This directly affects output, quality, and safety, while increasing overhead costs.

Professional skills are also difficult to attract and retain in mining. The mining industry competes with many other industries for professional talent, and mines are at a disadvantage due to the harsh conditions and remote locations in which they operate. At a global level, South Africa is losing professional skills to other countries as experienced professionals emigrate.

Executives are challenged to develop an understanding of the human resource capabilities required, and look to implement structures that attract, develop, and retain these skills. However, the dynamic nature of the industry (and the industries that drive resource demand) means that it will become increasingly challenging to balance the skills required today with the skills needed by mines in future.

How can mining companies raise the capital they need for their South African operations?

Investors are starting to attach a risk premium to South African mining investments. This has the effect of increasing the cost of capital to South African mining companies. Several companies have moved to separate their South African assets from their global assets, to help them raise capital for international investments. This leaves their South African assets cash-constrained and struggling to fund expansion projects.

Furthermore, many black economic empowerment (BEE) transactions are vendor-financed in a way that leaves the new company cash-constrained and unable to fund expansion projects. In an environment of rising costs and lacklustre commodity prices, South African executives have their work cut out to fund expansion out of operating cash flows.

How can mining companies determine the best and most sustainable use of capital?

Capital decisions are complicated by the global and South African factors influencing the current and future operating environment. The increasing regulatory uncertainty and volatile labour conditions in South Africa have substantially increased the country's inherent operating risk. These factors, coupled with increasing pressures from rising costs, have resulted in mining companies sometimes finding that producing more is not always more profitable. Mining companies have subsequently increased their thresholds for project profitability, abandoning projects that do not promise high enough returns.

In addition to local projects, mining companies have a myriad of options to consider elsewhere. The trend towards African exploration promises growth for mining companies willing to absorb the higher operational risks. Beyond the choice of geographic focus, mining companies must also assess which commodities are the most profitable and viable under the current conditions, and which commodities are of strategic importance for future growth. Finally, mining companies have the choice of investing in mature mines or developing early-stage operations.

How can mining companies balance the conflicting needs of stakeholders?

Mining companies have the unenviable task of balancing the needs of multiple stakeholders. Each stakeholder group has its own unique objectives, often conflicting with those of other stakeholders, as shown in Figure 4.

Government looks to maximize revenue to the state while ensuring that mining companies contribute to socio-economic and infrastructure development. Where the government has historically struggled to provide adequate services, mining companies are often used as a vehicle to accelerate change. The role of mining companies is further obscured by the fact that multiple arms of government are often not aligned, with inconsistent policy and populist rhetoric. Calls for distribution of the country's mineral wealth through resource nationalization have become increasingly popular with politicians looking to garner favour with the country's impoverished majority. While current government policy is against short-term resource nationalization, this policy stance may change in future depending on the success of other African countries that have implemented resource-based interventions to drive socio-economic progress.

Mining executives should also bear in mind that policy may shift without being considered a 'radical intervention' (for example, by increasing royalties or taxes on mining companies). These interventions can nevertheless have a significant impact on profitability and operational sustainability.

Similarly, labour, organized labour, and communities also expect mines to play an active role in socio-economic development. Mines frequently operate in areas with historically poor levels of service provision, and are often on the receiving end of decades of frustration due to a lack of tangible economic development, resulting in social unrest. The perception that international mining companies hoard wealth and do not share it with the communities in which they operate (despite the CSR investments that mining companies make) further threatens the fragile relationship between mining companies and communities.

While many shareholders appreciate the value of CSR initiatives, the increasing requirements for mining companies to invest in broad service provision activities makes it difficult for them to balance their responsibility to the shareholders and their responsibility to the community. Mining companies, as is to be expected, look to maximize profit while retaining a social licence to operate. The fluid and increasing government and community expectations mean that mining companies are not always willing or able to deliver social projects to the levels expected. Even when companies are willing to drive social change in their areas of operation, they often do not understand the communities' needs, and find that fulfilling needs identified by local municipalities sometimes also falls short of meeting community requirements.

Tools to assist decision-making

The tough questions facing mining executives require analytical tools as the basis for data-driven decision-making. Monitor Deloitte has identified five tools that can help mining executives understand the key issues underlying these challenging questions, as well as the strategies necessary to mitigate risk and take advantage of opportunities to create sustainable value.

Tool 1: take a long view

Mining companies can benefit from thinking about the long-term future by using tools such as scenario planning. Scenario planning allows mining companies to organize critical uncertainties about the future, along with predetermined elements, into a manageable set of scenarios that vividly describe potential future states of the world in which stakeholders live. Scenario planning was developed at Royal Dutch Shell in the 1970s as a tool to aid executives in making high-stakes decisions involving large investments and volatile situations, and it is clearly applicable to the mining industry.

The foundational proposition of scenario planning is that no-one can predict the future. However, mining companies can choose to adopt a disciplined and imaginative point of view about possible futures by focusing on key interactions among critical uncertainties and how these interactions could reasonably play out. Furthermore, scenario planning also generates early indications that can act as warning signs of danger, or even more valuable early indicators of high-value opportunities, some of which are barely visible or unlikely at the point at which an investment decision is made.

Case study: take a long view

A decade ago, miners had great hopes for the investment potential of Zimbabwe. Despite ongoing political turmoil, Harare was signalling a new openness to foreign investors. However, in 2011, the Zimbabwean indigenization minister moved to enforce a previously unenforced law limiting foreign ownership in the mining sector. This left mining companies with three choices: (1) comply with the law, ceding 51% of their stake, (2) refuse to comply and fight for their stake, or (3) walk away from their investment. This presents a tough choice. Scenario planning a decade ago may have thrown up a potential indigenization scenario, and would have helped executives develop a strategy that could survive in this scenario, as well as provide the tools to identify the scenario as it developed.

Tool 2: optimize portfolio

The new reality of volatile prices and rising costs means that companies have to optimize their portfolios by acquiring and mining high-quality assets with better grades and strong margins, while ceding low-margin assets to junior miners.

Mining company board members and executives face difficult trade-offs between competing strategic objectives, especially when it comes to projects with significant capital requirements. While in-depth financial modelling is critical, decision-makers need to move beyond simply prioritizing projects by value metrics such as NPV or IRR. Companies must assess the tangible and intangible benefits of projects under consideration. While evaluating intangible benefits is often subjective, mining companies can assign quantitative measures to these benefits, allowing projects to be compared on a value basis.

Capital allocation models in mining can be further improved by adopting principles from modern portfolio theory. Widely used to assess the value of stocks and other investment instruments, portfolio theory allows mining companies to prioritize projects using a risk-adjusted capital allocation model. Methods that account for risk are especially crucial for mining companies strongly influenced by global uncertainties such as exchange rates, commodity prices, and political risks, over and above the project-specific risks.

Executives are also faced with the decision to allocate capital to growth projects, or sustaining capital to existing projects. As the market expects healthy project pipelines, companies are under pressure to ensure that they are well-positioned to analyse, select, and implement key projects. Allocating sustaining capital is often more difficult, as the strategic objectives between projects vary greatly, making it difficult to directly compare the return on capital allocations.

Case study: optimize portfolio

In June 2013, Sentula Mining announced that it would sell off its coal assets (including its contract mining and exploration operations in Mozambique), as part of a strategy to dispose of non-core assets to focus on its core businesses (Business Day, 2013b) in line with similar disposals by global mining companies such as Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton (Bloomberg, 2013). By focusing its activities on key geographies and commodities in clearly defined parts of the value chain, Sentula Mining made the complex choices of where to play' and 'how to win in chosen markets'. This strategic decision will streamline Sentula Mining's capital allocation process.

Tool 3: innovate aggressively

During challenging times such as these, mining companies can choose to pursue a 'survival strategy' or a 'leadership strategy'. Those pursuing a survival strategy will cut costs to the bone while adopting a risk-averse posture and focus on defending their core business. Other companies adopt a leadership strategy, looking to identify unusual opportunities that will enable them to gain ground during the downturn and to make step changes in performance.

Mining executives often associate innovation with technology. While this is often the case, there are many different ways in which a company can innovate, as shown in Figure 5.

There is no lack of innovative ideas in any business. The challenge is turning these ideas into a step change in results. Good ideas often fall foul of resistance to change, and a failure to understand the whole system of innovations required to make the idea successful. For example, a new mining technology for the mine of the future will inevitably require innovative thinking in skills provision, mine planning, and performance measures. Mining companies should focus their innovation efforts on the few critical projects that will achieve a step change in performance and then move quickly. It is also not necessary to 'reinvent the wheel'. Many of the most successful innovations started with an idea from outside the company.

Tool 4: engage proactively with stakeholders

Mining companies operate in a complex stakeholder environment. As stakeholder understanding is often unstructured, mining companies can adopt a far more analytically rigorous approach to defining and understanding the stakeholder mind-set. Mining companies often take a too narrow view of their stakeholder landscape, missing interde-pendencies and 'new' groups whose interests will be mobilized over the course of the project's lifespan. Mining companies should develop a sophisticated stakeholder map, a living document that evolves over the life of the project and presents new opportunities to improve understanding and communication, and most importantly, to find new common ground.

Equipped with a deep understanding of stakeholders' needs, mining companies must choose to engage constituents in a deliberate and thoughtful manner that takes a long-term view and seeks to build productive relationships. At its core, this integrated, long-term constituent management approach extends beyond a particular project; it is a highly customized, data-driven process that provides a deep understanding of constituents, the interrelationships between them, how they are influenced by prominent issues, and how companies can build platforms to engage these constituents to achieve mutually beneficial objectives.

Case study: engage proactively with stakeholders

The Pilbara region of Western Australia, home to the Aboriginal people, has some of the largest iron ore deposits in Australia. The area contains many sacred areas and burial sites. In 2005, Rio Tinto began to explore the possibility of putting in place a comprehensive agreement with local stakeholders. After gathering social data, it built relationships with key stakeholders and developed community programmes. Seven years later, Rio signed a $2 billion agreement with five Aboriginal groups, giving the company access to 70 000 km2of traditional land to mine. By understanding communities' needs and creating shared value through their mining activities, Rio Tinto's shareholders have benefited as much as the Aboriginal people.

Tool 5: manage costs adaptively

Mining firms should make conscious decisions about their overhead ratios. Some companies manage their overhead ratios according to economic cycles, cutting overheads during recessionary periods with either less focus on cost optimization during periods of growth, or actively allowing for increased costs to fuel capabilities that drive growth. Rather than allowing for cyclical cost fluctuations, mining companies should manage their overhead ratio consistently over time. Research has shown that companies that consistently manage their overheads fare better than those with more volatile overheads, as shown in Figure 6.

Mining companies can approach adaptive cost management by mapping their costs against four main groups to gain a deeper understanding of where to create value. The return on each overhead class can then be calculated, allowing firms to prioritize and optimize costs, focusing on value-creating activities throughout the cycle, as shown in Figure 7.

Conclusion

Mines currently face tough choices around their profitability, attracting and developing key skills, capital raising, capital allocation, and stakeholder engagement. Mining executives need to think strategically about these issues and integrate them into a sustainable long-term strategy.

The rising pressure on mining companies to grow profits despite a sub-optimal macro-economic environment and rising costs requires in-depth analysis. Mining executives can use scenario planning to understand possible futures as the basis for informed decision-making in an uncertain environment, and then optimize their portfolio accordingly. Seizing opportunities to innovate, from technological breakthroughs to internal process changes, offers mines a further opportunity to control their future. With limited revenue potential due to unfavourable commodity prices, mining companies may seek to defend their profits by managing costs and streamlining their overhead portfolio to focus on cost categories that drive growth.

Mining companies should also welcome innovation to address the critical skills shortages affecting the industry. Scenario planning may also be useful to structure thinking around the kinds of skills that will be required for mining in the future. This will provide the basis for developing strategies to attract, develop, and retain these skills to secure future capabilities.

Furthermore, mining executives face difficult capital allocation decisions. By integrating lessons learned from scenario planning to create an understanding of which projects will develop the mining company's sustainable advantage in future, mining executives can adopt aspects of modern portfolio theory to analyse and select appropriate projects to deliver shareholder value.

Finally, mining companies must take cognisance of their operational context, especially in South Africa. The mining industry must understand and anticipate the needs of various stakeholders. Mining executives can use an analytical approach to understand the stakeholder landscape, ensuring that an effective stakeholder engagement strategy is in place. This strategy should seek to create shared value for stakeholders, resulting in mutually beneficial and productive relationships between the mining company, government, labour, and the community.

Even in tough times, mining companies can use strategic thinking and analytical tools to face their tough choices.

References

Bloomberg. 2 May 2013. European power prices slide to record as coal slumps on surplus. Bloomberg. www.bloomberg.co.za [Accessed 2 July 2013]. [ Links ]

Business Day Live. 5 May 2013. Mine deaths fall, but safety targets missed. BD Live. www.bdlive.co.za [Accessed 26 June 2013]. [ Links ]

Business Day Live. 28 June 2013. Sentula to sell coal assets as losses widen. BD Live. www.bdlive.co.za [Accessed 2 July 2013]. [ Links ]

Deloitte Market Intelligence, May 2013. Global Mining Update - May 2013: Taking the temperature of the market. [ Links ]

McNitt, L. 25 June 2013. A new type of colonialism? AgWeb. www.agweb.com [Accessed 26 June 2013]. [ Links ]

Sowetan Live. 3 August 2011. Nationalisation the wrong debate - Shabangu. Sowetan Live. www.sowetanlive.co.za [Accessed 26 June 2013]. [ Links ]

The National. 21 June 2013. Glitter comes off South Africa's gold. The National. www.thenational.ae [Accessed 26 June 2013]. [ Links ]

1 Throughout this paper, the term 'South African mining companies' is used interchangeably to refer to international mining companies with South African mining operations, as well as mining companies registered in (and with primary operations in) South Africa.