Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717

Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.113 n.1 Johannesburg Jan. 2013

MINERAL ECONOMICS

Making sense of transformation claims in the South African mining industry

G. Mitchell

Independent Mining Policy Consultant

SYNOPSIS

Much debate has ensued over the past few years on the speed of transformation in the mining industry. By transformation is meant the degree to which the industry has met the requirements of the Mining Charter. In response to this, the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) commissioned a research study in 2009 to ascertain the degree of industry compliance. The mining industry in response made a presentation to the Minerals Portfolio Committee in Parliament in 2011, during which it released aggregated figures on industry compliance to the Mining Charter. The conclusions of both of the studies are widely divergent. It is argued in this paper that both processes are flawed. The government-sponsored research is empirically and methodologically weak and the results therefore have to be taken with a great degree of caution. The Chamber of Mines figures, on the other hand, while faithful to the reporting of the Chamber member companies, do not represent the entire span of the industry but only the larger mining companies. It is further argued that in order to ascertain a true reflection of the industry an independent audit be undertaken using recognized social scientific survey methods.

Keywords: South Africa, MPRDA, mining charter, mineral policy.

Background

The Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA) of 2002 took a period of approximately ten years to negotiate between the various industry, government, and community stakeholders. Starting with the release of the draft ANC Mineral and Energy Policy document in 1990 (ANC, 1990) it took as its point of departure the Freedom Charter of 1955 (Congress of the People, 1955), which stated that in relation to minerals and industry:

the national wealth of the country, the heritage of all South Africans, shall be restored to the people;

the national wealth of the country, the heritage of all South Africans, shall be restored to the people;

the mineral wealth beneath the soil, the banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole;

the mineral wealth beneath the soil, the banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole;

all other trade and industry shall be controlled to assist the well- being of the people.

all other trade and industry shall be controlled to assist the well- being of the people.

The MPRDA, which was based largely on the ANC draft Mineral Policy document (ANC, 1990), posed a radical departure from past mining policy and legislation. It placed the state as the custodian of the nation's mineral resources and, as a consequence of this, introduced a number of obligations that mining companies needed to fulfill in order to obtain a mining or a prospecting right. The MPRDA was given further impetus by the release of the Mining Charter in 2004 (DMR, 2004), which was reviewed in 2009.

The key objective of the Mining Charter is to accelerate black economic empowerment (BEE) in the industry. The Charter centres around the following pillars: human resource development, employment equity, migrant labour, mine community development, housing and living conditions, procurement, ownership and joint ventures, beneficiation, and reporting. Each of the pillars of the Charter has targets that were agreed to by the various industry stakeholders, set over a ten-year time frame (to be further reviewed in 2014). As the five- year review date approached in 2009, the various stakeholders compiled statistics on the extent of Charter compliance and progress made over the period.

In 2009, the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) commissioned a research study into Charter compliance (DMR, 2009). The South African Mining Development Association (SAMDA) in 2010 commissioned a report by Kio Advisory Services, but subsequently distanced itself from the findings (South African Mining Development Association, 2010). In August 2011, the Chamber of Mines (Chamber) made a presentation to the Portfolio Committee on Mineral Resources, releasing aggregated figures from Chamber member companies on Mining Charter compliance (Chamber of Mines of South Africa, 2011).

This paper attempts to establish progress to date using these sources, as well as identify problems in implementation and the current strategies in place. What will be highlighted is the wide discrepancy in the findings of the DMR research document and the figures released by the Chamber on transformation in the industry.

DMR and Chamber of Mines reports

It must be stated at the outset that it is difficult to establish the accuracy of the DMR-commissioned report as the authors do not state how the research was conducted, the sample size, or the methodology employed. What is presented are a set of statistics and some explanations of these statistics.

The Chamber presentation, in comparison, presents a set of statistics indicating progress on the Charter by its members as well as some of the identified problem areas. However, it must be noted that the Chamber represents the larger mining companies, and the majority of mining companies in South Africa, particularly the junior and smaller companies, are not members of the Chamber. The Chamber data is compiled from 33 companies using the DMR reporting template. A simple average is calculated from the data to arrive at an industry average. So comparisons are difficult, although an attempt will be made to extrapolate the key findings from both the Chamber and DMR documents. The problem is that they start from different premises (save for using the headings taken from the pillars of the Charter), and the exercise is therefore not comparing 'apples with apples'. The comparisons follow under a series of headings, beginning with human resource development.

Human resource development (Skills Development Act 97 of 1998)

Adult Basic Education and Training (ABET) accounts for most of the spend by companies on education and training (Mitchell, 2010a). According to the Mining Qualifications Authority (MQA) 14 000 employees completed ABET in 2010. ABET was negotiated as a priority area because it is a requirement for any form of formal skills development in the industry and allows employees the opportunity to enter the National Skills Framework.

The DMR research claims that ABET is not being effectively implemented. It is claimed that employees have to attend ABET after hours and there is no incentive to do ABET.

The Chamber research indicates that a human resource development spend of 4.6 per cent by companies on ABET exceeds the 3 per cent target for 2010. The industry itself is critical of ABET, largely because there is little opportunity for employees to practice ABET in the workplace. A compounding factor is that many of the underground workers are older that forty and do not see the need for ABET. Fanagolo is still in most cases the lingua franca on the mines.1 So there are clearly a number of challenges that need to be addressed.

The DMR report also asserts that there is no proper career path or progression plans and that there is little relation between what the companies submit in their skills development plans and what actually occurs. Career pathing tends to concentrate on higher level employees who, it is noted, are mainly white males.

Employment equity

The DMR research claims that only 37 per cent of companies have developed employment equity plans, and that there is no evidence of employment equity plans submitted to the DMR. It also claims that 26 per cent of mining companies have achieved a 45 per cent threshold of historically disadvantaged South African (HDSA) participation at management level, while the overall industry average is 33 per cent. Only 26 per cent of mining companies have complied with the 10 per cent target for women in mining.

The Chamber, on the other hand supply the following figures for HDSA targets reached; top management - 28 per cent, senior management - 36 per cent, middle management -42 per cent, and junior management - 56 per cent. According to Chamber figures, female employees make up 9 per cent of senior management and 16 per cent of middle management. This indicates the wide discrepancy between the DMR and Chamber findings.

Mine community development

Another pillar of the Charter and an important part of the social and labour plans (SLPs) is community development, which generally refers to the engagement of communities prior to mining, and the identification of community development priorities. There are international best practices in this regard issued by the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM).2 In practice, community development usually involves education projects, such as early child development, high school support services, upgrading classrooms and equipment, and teacher support. Health community development comprises of HIV education, clinic upgrading, health education, immunization and upgrading hospitals. Welfare and development usually consists of social support programmes, waste management, recycling, and upgrading of community infrastructure (Mitchell, 2010a).

According to the DMR, 63 per cent of companies engaged in consultation processes with communities, while 49 per cent participated in integrated development plans. Only 14 per cent extended their plans to labour-sending areas, and 37 per cent showed proof of expenditure in accordance with the SLPs.

It was noted that efforts to integrate community development plans involving collections of mining companies acting in unison was commendable. Here the DMR is probably referring to the various producers' forums. For example, the Platinum Producers Forum was started a few years ago in response to the need for platinum producers in the Rustenburg region to address structural and community development issues around mining. In addition to the problem of electricity supply, the platinum producers were faced with water shortages as well as a lack of adequate road infrastructure.

The main function of the Forum is to improve the delivery rate of sustainable projects in collaboration with communities by ensuring that there is a common understanding of the problems at hand and no duplication of efforts in addressing these problems (Mogotsi, 2011).

The Platinum Producers Forum, which comprises of most of the mining companies in the area, identified ways in which the producers could pool resources and try and address these largely structural problems. Developing from these meetings the forum engaged local municipalities in rolling out the infrastructure development model. As a logical outgrowth to this process communities in the vicinity of the mines could potentially benefit from improved roads and access to water (Chamber, 2011b).

Producers fora are being replicated in the coal and gold sectors, as the industry believes that integrated development in a mining region is a more rational use of resources, can promote planning that includes the community, and has the ability to attract outside funding.

According to the Chamber, its members spent R961 million on community development in 2010. This is the biggest expenditure on corporate social investment (CSI) of any sector in South Africa. The Chamber notes that clarifications need to be sought on the formula for CSI spend and that the 'costs proportionate to size of investment' needs to be clarified.

Housing and living conditions

The DMR research notes that 26 per cent of mining companies have provided housing for employees, while 29 per cent per cent have improved existing standards. According to the DMR research report, 34 per cent of companies have facilitated home ownership, while 29 per cent have offered nutrition to employees or effected plans to improve nutrition. Occupancy rate has been reduced from 16 per room to 4 per room.

The Chamber, on the other hand, notes that most of its members do not have hostels. Chamber figures for single occupancy rate for 2011 is 24 per cent. According to the Chamber, housing is affected by the life of mine and inability of local municipalities to provide basic services (electricity and water) for the upgrading of accommodation.

Home ownership is another option for employees as set out in the Charter; however, it has proved to be fraught with problems. Those who earn below R3500.00 per month are eligible for social housing subsidies (RDP housing) and generally people who earn above R10 000.00 per month are eligible for loans from commercial banks. The group that earn between R 3500.00 and R 7500.00 per month do not qualify for either, and are referred to as the 'gap market.' There is an estimated 1 8 million people who fall into this category in South Africa.3

The Department of Human Settlements has initiated a fund to address this particular sector. It works as a financed linked subsidy, whereby companies manage the subsidies on behalf of employees.

Generally the subsidy has not had a great take-up and has not been that successful4 Unless the company provides family accommodation, employees of mining companies are not that keen to buy as many come from areas away from the mine and would rather purchase houses there. A second issue is credit worthiness: employees in this group tend to be indebted for other consumables such as cars, TVs etc. thus making the purchase of a home beyond their reach.

One unintended consequence of the Charter with respect to housing is the practice of mining companies giving 'living out allowances' as an option to company accommodation. This has been particularly prevalent in the coal sector, where employees are offered living out allowances and have ended up living in informal settlements, due in part to the shortage of housing stock in the vicinity of the mine. Clearly this pushes the onus onto the local municipalities who in most cases lack the resources to deal with the problem.

Procurement

The Charter stipulates that by 2014 mining companies must procure a minimum of 40 per cent of capital goods from black economic empowerment (BEE) entities and 70 per cent of services and 50 per cent of consumer goods by that date. A 'BEE Entity' is defined as an entity of which a minimum of 25% + 1 vote of share capital is directly owned by HDSA as measured in accordance with the flow-through principle.

The problem in the definition in the Charter is that procurement does not stipulate local BEE entities, with the result that any BEE national entity can become a supplier to the mine. In practice, a lot of procurement services are supplied by well-established politically connected BEE entities, and local communities do not see the benefits at all. In implementing a more locally-based model, however, a lot of support for local BEE suppliers would be required as they usually lack the required experience. However, one or two larger contracts to local BEE suppliers could make a huge economic impact on communities directly affected by mining.

The DMR research indicates that 89 per cent of companies have not given HDSA suppliers preferential status, while 80 per cent have not indicated commitment to the progression of procurement over a 3-5 year time frame. The value of procurement as a percentage of total procurement is 3 per cent according to the DMR estimate. It is claimed that procurement mainly consists of non-core activities such as cleaning and food supplies to the mines.

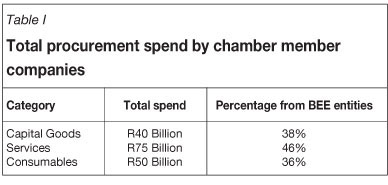

The Chamber, on the other hand, estimates that the total procurement spend for the mining industry is R 228 billion.5 Total spend by Chamber members is R165 billion as illustrated in Table I.

In support of preferential procurement, the South African Preferential Procurement Forum (SAPPF) was set up in 2002 in order to develop a database of HDSA suppliers. These suppliers can then be accessed by mining companies in order for them to meet the requirements of procurement stipulated in the Mining Charter. A not-for-profit organization, the SAPPF has mining company members who then have access to the database of BEE-accredited suppliers.

A vendor is accredited only after a process conducted by the South African Mining Preferential Procurement Forum (SAMPPF) personnel, BEE rating agencies such as Empowerdex, or consulting firms. The vetting process takes into account the 'economic and legal ownership' of the firm by HDSAs as well as involvement in day-to-day management. Also scrutinized are the structure of the company, the types of shares held by HDSAs, funding, statutory documents, dividend policies, economic risk, and access to information. Vendors on the accredited list are monitored every year to ensure that they continue to comply with the requirements. An accredited supplier can be a black-owned, black-empowered, or black-influenced company. An empowering supplier is one that has embarked upon a measurable BEE development programme of its own, and this could include employment equity, skills transfer, and buying from BEE companies (Zhuwakingu, 2004).

Despite the formalization of preferential procurement through the above measures, the DMR remains deeply skeptical of preferential procurement efforts and feels that communities affected by mining are not securing sufficient contracts.

Ownership

Perhaps the one pillar of the Mining Charter that has caused the most debate is that of ownership. The DMR estimates the current asset value of the industry at R2 trillion, indicating that 15 per cent HDSA ownership at current rates would requires R300 billion. The original Charter agreement was a commitment to R100 billion (in 2004 terms) by the mining industry to HDSA ownership levels (DMR, 2004). The DMR research therefore asserts that R100 billion represents only 5 per cent of current net asset value of the industry. It claims that ownership at present is no more than 9 per cent and by far the biggest bulk is concentrated in the hands of anchor partners or special purpose vehicles (SPVs). In terms of ownership, according to the DMR report:

'The underlying empowerment funding model has resulted in the actual ownership ojmining assets intended jor transformation purposes being tied in loan agreements. Accordingly, the net value of a large proportion of empowerment deals is negative, due to high interest rates on the loan and moderate dividendjlows, compounded by the recent implosion of the globaljnancial markets. The rapacious tendencies oj the capital markets have consistently thwarted the intended progress towards attaining the goals oj transformation, as embedded in the Charter.' (DMR, 2009).

Also mentioned is the lack of HDSA representation at board levels and, as a consequence, the lack of involvement in decision-making on strategic issues.

The Chamber estimates that the weighted average on ownership in the industry is presently at 28 per cent, as measured according to the Charter. In addition, savings retirements are increasingly black-dominated. Some challenges are to ensure that future deals are sufficiently broad-based, that there is sufficient cash flow for the BEE partner, and the dilemma of full ownership versus lock-in guarantees.

It would appear that the original estimates on the value of the industry and the value of the 26 per cent BEE quota has now been replaced by the DMR with a new estimate, and this has changed what companies can claim as BEE ownership levels. An agreement needs to be reached by all parties on what the current value of the industry is and how the BEE ownership quotas are to be calculated so that measurement levels can be ascertained.

Because the data presented by the Chamber on the one hand, and the DMR research findings on the other hand are so diverse, the Minerals Portfolio Committee (MPC) asked for individual companies to make submissions with respect to BEE ownership.

BHP Billiton, the world's largest resource company, said it was committed to South Africa and was investing R1.5 billion in manganese expansion projects in the Kalahari, R800 million in the Hotazel town development project, and R715 million in the M14 furnace project in Gauteng.

The Committee asked how the company had structured empowerment deals, as they had already met the 26 per cent empowerment target. BHP Billiton replied that their BEE partners were given equity on land that they bought into the deal, and that deals were never structured too onerously for the partners (Lund, 2011a).

Anglo American claim to have reached 26 per cent BEE ownership. Godfrey Gomwe, the chief executive officer, said that the government research calculated ownership only at holding company level, while ownership at asset level was overlooked. Gomwe said that Anglo had concluded R60 billion in BEE transactions since 1994, and had been responsible for setting up a number of BEE companies such as African Rainbow Minerals, Exxaro, Mvelaphanda, and Shanduka. The committee wanted to know the degree of indebtedness of these transactions, which was a result of the loss of BEE equity following the 2008 financial meltdown. Gomwe said that Anglo had acted like a bank and contributed towards vendor funding (Lund, 2011b).

In a snap survey conducted by SAMDA on junior mining BEE transactions in 2010, it was found that with junior companies, the larger and more established the company, the more likely it was to provide protection for the BEE partner. Smaller companies expected the BEE partner to raise its own capital for the transaction, and this often resulted in these BEE entities diluting their shareholdings in order to raise finance for expansion projects (Mitchell, 2010b).

Beneficiation

Perhaps the pillar of the Charter least developed is that of beneficiation. This is a bit of a paradox in view of the fact that it is the one area of the Charter in which a company can offset credits for ownership.§ The DMR report notes that there have been pockets of local beneficiation of mining companies, albeit in an uncoordinated manner. The report also notes that the Charter review provides an opportunity for the strengthening of beneficiation in line with the National Industry Policy Framework.

Although beneficiation is an important strategy for South Africa, the Chamber does not report on it. This may be due to the complexity of the subject, or else mining companies are not taking sufficient advantage of the potential and the incentives involved.

The government has made progress in putting in place funds to support the process. As Lydall (2012) notes:

'In support of the NGP's and Beneficiation Strategy's emphasis on attracting new investors, the IDC has allocated approximately R102 billion over the next five years to advancing mineral beneficiation, manufacturing and agricultural activities in South Africa. Through its Mining and Metals Beneficiation Strategic Business Unit, the IDC will offferfinancial and technical assistance to mining-related enterprises that have a significant development component and promote job creation and value chain development. In October 2011, the Minister of Finance unveiled a R25 billion support package over the next six years to boost industrial development, assist entrepreneurs and accelerate job creation in the country. The Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) through its industrial development zone (IDZ) at Coega, aims to facilitate the 'clustering' of ferrous and non-ferrous metal manufacturing enterprises through the provision of various services and favourable business environment. Greater awareness of the requirements for accessing and participating in these various initiatives, appropriate beneficiation levels per commodity, and offf-set requirements needs to be communicated timorously to industry in order to ensure that viable opportunities for advancing beneficiation are expedited as smoothly and as efficiently as possible:

Reporting and compliance

According to the DMR only 37 per cent of companies have audited reports, while only 11 per cent purport to have submitted their progress reports to the DMR. It is also alleged that mining company compliance data is not subject to independent audits by BEE verification agencies.

The Chamber claims that its members have, as far as they can ascertain, submitted compliance reports both to the Chamber and to the DMR.

It seems odd that these views are so divergent. The DMR admits that it has no system in place to enforce compliance.

KPMG (2012), in its annual BEE compliance survey, which covers a wide range of JSE and multinational companies including mining companies, found that 90 per cent of these companies used BEE rating agencies in monitoring compliance.

Conclusions

The evidence on the extent of transformation in mining in South Africa is, at best, unreliable. This is because there has been no systematic survey, using a commonly agreed baseline, on the impact of the Charter on the mining sector.

The government is deeply suspicious of the statistics provided by both the Chamber and individual mining companies, while the industry regards the government-sponsored research as inadequate and not sufficiently well researched to present an accurate estimate on the extent of transformation in mining. What is needed is an independent audit that starts from an agreed premise (for example, the current financial size of the industry) and includes a cross section of the industry and not just a sample of big companies represented through the Chamber of Mines.

Mining policy development and implementation requires decision-making informed by reliable and credible data. Currently the government sponsored State Intervention in the Minerals Sector (SIMS) report on resource nationalization advances a number of areas of policy review (ANC, 2012). It would seem somewhat premature, however, to advocate major mining policy reform without having established accurately the impact of current legislation on the mining and minerals sector.

References

ANC (African National Congress). 1990. Draft Mineral and Energy Policy. Discussion document, African National Congress, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

ANC (African National Congress). 2012. Maximising the development potential of the people's mineral assets: state intervention in the minerals sector. [ Links ]

Chamber of Mines of South Africa. 2011a. Progress with the implementation of the Mining Charter. Presentation to the Portfolio Committee on Mineral Resources, Aug. 2011. [ Links ]

Chamber of Mines of South Africa. 2011b. Mining Community Development News, February 2011. [ Links ]

DMR (Department of Mineral Resources). Broad Based Socio Economic Charter for the South African Mining and Minerals Industry. Pretoria, 2004. [ Links ]

DMR (Department of Mineral Resources). Mining Charter Impact Assessment Report. Pretoria, oct. 2009. [ Links ]

KPMG. 2012. The evolution of BEE measurement. KPMG survey, [ Links ]

Lund, T. 2011a. BHP Billiton affirms SA committment before MPs. MiningMX, Nov. [ Links ]

Lund, T. 2011b. MP's face-off over BEE targets. MiningMX, 2 Nov. 2011. [ Links ]

Lydall, M. In: The Rise of Resource Nationalism: A Resurgence of State Control in An Era of Free Markets or The Legitimate Search For A New Equilibrium? Solomon, M. (ed.). Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, Johannesburg, 2012. [ Links ]

Mitchell, G. 2010a. Worksop with Teba Management; Identifing Community Development opportunities. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Mitchell, G. 2010b. Survey of SAMDA member companies on methods of financing BEE transactions. South African Mining Development Association, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Mogotsi, C. and Rea, M. Sustainable Mining in the 21st Century. SAMDA, 2011. [ Links ]

South African Congress Alliance. 1955. The Freedom Charter. As adopted by the Congress of the People, Kliptown, on 26 June, 1955. South African Mining Development Association. Press statement - 14 October 2010. http://www.samda.co.za/downloads/SAMDA_Press_Release.pdf [Accessed 10 Nov. 2012] [ Links ]

Zhuwakingu, M. 2004. Preferential procurement body continues to grow. Mining Weekly, May. [ Links ]

© The Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 2013. ISSN2225-6253. Paper received, 1-2 August 2012.

1 The author has worked as a skills facilitator for the MQA and these observations are based on information obtained from practioners in the industry

2 The ICMM has a department dedicated to community development issues

3 Mining companies may offset the value of beneficiation achieved by the company against a proportion of its HDSA ownership requirements but not exceeding 11 per cent

4 The author sat on the Coal Task Team for Housing and living Conditions, at the Chamber of Mines in 2010

5 Chamber of Mines, 2010