Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717

Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.112 n.12 Johannesburg Jan. 2012

Patenting in the field of percolation leaching

R.F. Taberer

McCallum, Rademeyer and Freimond, Randburg, South Africa

SYNOPSIS

Within the technology field generally known as biological heap leaching or percolation leaching, lies a wealth of technological knowhow that is potentially patentable and therefore can form the subject matter of patent applications.

An organization often overlooks the potential for generating intellectual capital during its research by dismissing the possibility that what it is working on may be novel and inventive and therefore patentable. The organization labours under the misconception that there is nothing patentable in its work mainly because the novel aspect is overlooked against the general background state of the art or, if identified, is not recognized as having sufficient inventive merit.

In the field of biological heap leaching, patents have issued on inventions that extend across a large range of technology, including microbiological inventions-for example a particular strain of microbe used in a heap leach application, electro-mechanical inventions, for example a column simulator that simulates the heap leach environment, and thermodynamic inventions such as methods of generating and maintaining heat in a heap.

Keywords: percolation heap leaching, heap bioleaching, patenting, microorganisms.

Introduction

Percolation leaching is a technologically active field in which innovation is advancing on many fronts. Although the broad principles of percolation leaching, and the methodology employed, are many decades old, there still remain many niches, within this broad field, in which the opportunity to patent exists.

General patent principles

For an invention to sustain a valid patent, the invention must be objectively new, subjectively inventive, and industrially applicable.

An invention is objectively new if, as of the date of filing of a patent application defining the invention, all elements or aspects of the invention have not been made available to the public, anywhere in the world, by means of publications, papers, patent applications, or commercial disclosures.

If an invention is new, it must also be inventive, i.e. it must not be obvious or, conversely, it must contain an inventive step. The test whether a new concept is inventive and therefore qualifies, from a legal perspective, as an invention is as follows:

Will a person who is skilled in the relevant art, faced with the technical problem that gave rise to the invention, modify or adapt the prior art to arrive at the invention?

If the skilled person would be prompted to modify the prior art, then the invention does not include an inventive step and the patentability of the concept fails on the second hurdle.

A patent application, on grant, gives rise to a patent that vests the owner with the right, within the country or territory in which the patent application was filed, to exclude third parties from exercising, making, disposing of or importing, in or into the particular country or territory, the invention during the currency of the patent application.

The right described above is termed a negative right, i.e. a right to exclude, rather than a positive right, i.e. a right to exploit. The absence of a positive right to exploit or exercise is in recognition that the invention, the subject matter of the patent, is built on the foundation of the prior art i.e. prior innovation, which is often the subject matter of third-party rights. In other words, if the patent granted the patentee a positive right of exploitation the right could erode a third party's rights vested in the prior art.

Patenting possibilities in the field of percolation leaching

Within the context of percolation leaching, there exist a number of technical sub-categories within which new and innovative developments may justify patent protection:

a) Micro-organisms for use in percolation leaching

b) Process modelling methods and apparatus used therein

c) Apparatus for use in percolation leaching

d) Methods of effecting percolation leaching.

Examples of patents in each of the sub-categories

A micro-organism for use in percolation leaching

An example of an existing patent filed in this sub-category is United States patent No. (US) 7,601,530 which is entitled 'Bacteria strain Wenelen DSM 16786, use of said bacteria for leaching of ores or concentrates containing metallic sulfide mineral species and leaching processes based on the use of said bacteria or mixtures that contain said bacteria' (Sugio et al., 2006).

The patent claims an isolated bacterial strain which belongs to the species Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, named Wenelen, and deposited as DSM 16789 at the DSMZ (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany).

The DSM 16786 is further defined as a strain which is a gram-negative bacterium that grows by oxidizing iron and elemental sulphur, a compound resulting from the bioleaching of sulphide minerals or ores. The micro-organism has a particular 16S rDNA sequence which is defined in the specification to the patent and an extra-chromosomal element of approximately 15 Kb with an autonomous replication sequence; and which shows an increased activity for leaching of metallic sulfide ores (Sugio et al., (2006).

Process modelling methods and apparatus used therein

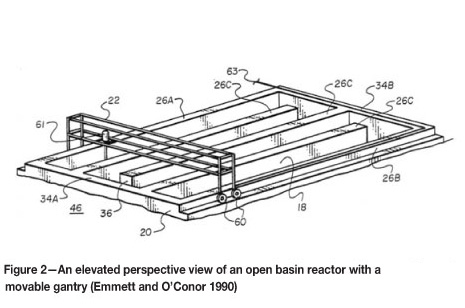

An example of a patent in this technical sub-category is US 7,727,510, entitled 'Method and apparatus for simulating a biological heap leaching process' (Van Buuren, 2005).

This patent describes a microbiological heap leaching simulation process in which material, representative of ore in a heap, is microbiologically leached in a simulation column (Figure 1) and the temperature of this material, at a plurality of locations in the column, is monitored and controlled to reduce heat loss from the housing.

The patent claims a method of simulating a process in which ore, in a heap, is microbiologically leached, the method including the steps of microbiologically leaching material, representative of the ore, in a housing (10, 12) defining an enclosed, confined volume, monitoring (72) the temperature of the material, inside the volume, at each of a plurality of locations (48) to assess the leaching activity at each location and, in response to the monitored temperatures, separately controlling the operation of each of a plurality of heat sources (50) which are positioned at predetermined locations within the confined volume to control (48) heat loss from the confined volume effectively to zero (Van Buuren, 2005).

Apparatus for use in percolation leaching

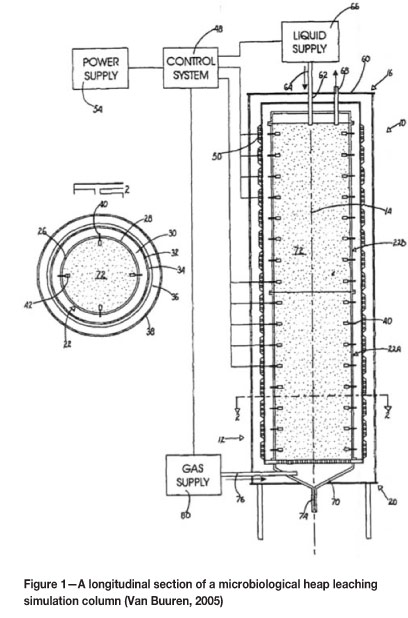

An example of a patent in this particular technical sub-category is US 4,968,008, entitled 'Bioleaching apparatus and system' (Emmett and O'Connor, 1990).

The patent claims a reactor (18) (Figure 2) for use in processing metal-bearing solids through use of a bioleaching process the reactor comprising:

an open basin (20) adapted to retain a quantity of metal-bearing concentrate slurry, the open basin having a bottom, an inlet and an outlet, the open basin including a plurality of linear, elongate channels positioned adjacent and parallel one another, at least one of the linear, elongate, channels communicating at each of its opposing ends with a respective linear, elongate channel positioned adjacent thereto, the open basin defining a flow path between the inlet and the outlet

an oxygen introduction means, positioned within the open basin proximatefor injecting an oxygen containing gas into the slurry within the open basin

a gantry (22), mounted atop the open basin for movement along a length (26) of the open basin; and

an agitation means (61), mounted on the gantry for movement therewith, for re-suspending coarse solids which have settled on the open basin bottom proximate the oxygen introduction into said metal-bearing concentrate slurry (Emmet and O'Connor, 1990).

A percolation leaching method

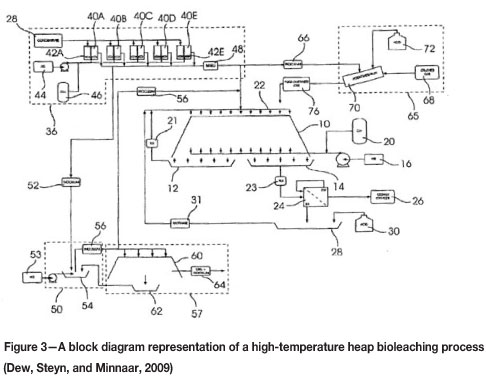

An example of a patent application filed in this technical sub-category is US 2011023662, entitled 'A high temperature leaching process' (Dew, 2009).

This example is a patent application. A patent, as yet, has not been granted on the application.

The application (Figure 3) discloses, describes, and claims a method of conducting a bioleaching process to recover metal content from an ore (76) which includes the steps of forming a main heap (10), culturing at least one iron oxidizing mesophilic or moderate thermophilic microorganism (52, 56) which exhibits bioleaching activity in a predetermined temperature range, monitoring the temperature in the main heap, which is a result, at least, of microbial leaching activity, adding carbon dioxide (20) to the main heap whilst the temperature in this heap is in the mesophilic temperature range and inoculating the heap with the cultured microorganism at least before the temperature reaches the predetermined range (Dew, Steyn, and Minnaar, 2009).

Patenting of micro-organisms

The most technologically active sub-category of the percolation leaching field, judging by patenting activity, appears to be the identification and isolation of novel strains of micro-organisms for use in this field. This technical sub-category therefore justifies special mention.

There are a number of legal hurdles that an inventor in this field sub-category must surmount in order to achieve a patentable invention.

Issues related to the patentability of micro-organisms

The mere finding or isolation of a micro-organism occurring freely in nature is a discovery. A discovery does not include an inventive step and therefore does not give rise to a patentable invention.

If a micro-organism is isolated and an inventive use (utility) is identified for the micro-organism then, in effect, the isolation and utility convert the discovery to an invention and the micro-organism could be patentable. An example would be micro-organisms isolated for use in heap leaching applications as described above. This position is reflected in Australia by the following statement: 'A biological entity may be patentable if the technical intervention of man (ie. manufacture) has resulted in an artificial state of affairs which does not occur in nature' (Australian Patent Office).

In all instances patentability is subject to normal requirements of novelty and inventiveness.

Particular examples of what has been considered to involve a technical intervention and therefore an inventive step achieving the patentability of a particular microorganism, are the following:

Isolation of a micro-organism and the identification of utility for the isolated microorganism

A claim to a pure culture in the presence of specified ingredients might satisfy the requirements of technical intervention

A new variant of a micro-organism that has improved or altered useful properties ('utility') and not merely changed morphological characteristics which have no effect on the working of the organism.

As a practical guideline:

It would be possible to patent the use of a known micro-organism where that use gives benefits that are not predictable. This is in keeping with a normal requirement for inventiveness

A claim to a micro-organism could be allowed if the micro-organism is newly isolated and if the isolated micro-organism has utility in a technical field. This would be a claim directed to the micro-organism by itself and not to the use of the micro-organism.

The Budapest Treaty

Disclosure of the invention, to the extent that a person skilled in the art can use the disclosure to practice the invention, is a requirement for the grant of patents. Normally, an invention is disclosed by means of a written description. Where an invention involves a micro-organism or the use of a microorganism, such disclosure is not possible in writing but can be effected only by the deposit, with a specialized institution, of a sample of the micro-organism.

A main feature of the Budapest Treaty of 28 April 1977, as amended on 26 September 1980 is that a contracting state must recognize, for patent procedure purpose, the deposit of a micro-organism with any 'international depositary authority', irrespective of whether such authority is in or outside the territory of the state. The Treaty eliminates the need to make a deposit in each country in which protection is sought.

An 'international authority' is a scientific institution that is capable of storing micro-organisms. Such an institution acquires the status of an 'international depository authority' through the furnishing of assurances to the Director General of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), to the effect that the institution complies, and will continue to comply, with the requirements of the Treaty. There are thirty-eight such authorities spread across the globe.

The Treaty is advantageous primarily to the depositor, as it enables the depositor to deposit a sample at one institution only, rather than depositing a sample in each country in which protection is sought, thus saving costs. It also provides a uniform system of deposit, recognition, and furnishing of samples of micro-organisms.

The Treaty was concluded in 1977 and is open to member states of the Paris Convention (at Paris, 20 March 1883, as amended), of which South Africa is a member.

Bioprospecting, prior informed consent and access and benefit sharing

Definition of bioprospecting

Bioprospecting is the removal or use of biological and genetic resources of any organism for scientific research or commercial development. When bioprospecting is pursued without the knowledge and prior consent of the 'owners' of the resources and without benefit sharing, the activity is called biopiracy.

For an innovator, bioprospecting is often an unavoidable first step to discovering, identifying, isolating, and using a micro-organism for use in percolation leaching.

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

Article 15 of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) marks a point of departure from the traditional way in which a country thought of, and dealt with, its genetic resources. Genetic resources, post-CBD, can no longer be considered part of the public domain to be exploited at will on a 'first come, first served' basis.

Article 15 of the CBD confers to a state a sovereign right to natural resources in its geographical area in the sense that the state, represented by its national government, has authority to determine, subject to relevant national law, who may access the natural resources and on what basis.

Although the state has authority to determine issues of access to the genetic resources, Article 15 does not imply that the state has a property right (ownership) over the resources.

In terms of Article 15, as embellished by the Bonn Guidelines, which is a published set of voluntary guidelines, the purpose of which is to give substance to the obligations of Article 15 in the absence of local law regulation, access to genetic resources by a third party is subject to prior informed consent (PIC) and utilization (which includes research and commercialization) of genetic resources is subject to fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from such utilization.

As the state has the sovereign right to control access to the genetic resources, the entity granting PIC must have state sanction to do so. This does not mean, though, that the recipient of the benefits arising from the utilization must be the state or a state agency, nor that the benefits have to benefit the state directly.

The beneficiary must be endorsed or proposed by, or be a representative of, the state and can, for example, include a local indigenous community, a university, or a municipality.

The CBD was ratified by South Africa in 1995.

Prior informed consent

For PIC to be legally unassailable, it must be granted by an entity or agency that has state authority to do so. It is incumbent upon a state, in terms of the Bonn Guidelines, to designate a national focal point (FP) which inter alia is tasked with granting PIC to access genetic resources, or identifying a relevant authority who can grant PIC, and establishing, endorsing, or agreeing upon the benefit sharing terms and conditions, in the event of research or commercial utilization.

The role of an FP is twofold:

either to grant PIC on application, by way of a permit, or to identify an appropriate authority or stakeholder who can grant PIC; and

to approve or endorse an allied benefit sharing agreement (BSA) when not a party thereto, or to become a party to a BSA, either on behalf of the state or a third party, such as a local indigenous community, being:

- a person, including any organ of state or community, providing or giving access to the indigenous biological resources to which the application relates; and an indigenous community;

- whose traditional uses of the indigenous biological resources to which the application relates have initiated or will contribute to or form part of the proposed bioprospecting; and

- whose knowledge of or discoveries about the indigenous biological resources to which the application relates are to be used for the proposed bioprospecting.

In the absence of prescriptive regulation, an application for PIC can take any appropriate form. It is recommended in the Bonn Guidelines that the following information should be included in the application:

Details of the applicant and, if the applicant is acting on behalf of a principal, details of the principal

The type or description of genetic resource to which access is sought

The starting date and anticipated duration of bioprospecting activities

The geographical prospecting area

An evaluation of how access and bioprospecting may affect the environment and, if there is an enironmental impact, how it is that the applicant proposes to minimize and correct this impact

The intended use of the genetic resource once found (e.g. research, commercialization)

Details of the entity tasked with bioprospecting and research functions

An undertaking, if the genetic resource is found, to provide the resource with a unique identification and to make disclosure thereof at least to the FP, and to provide regular feedback during subsequent research and commercialization stage;

An undertaking to deposit a sample of the genetic resource with a pre-identified depository subject to issues of access and transfer of the genetic resource to third parties being clearly established, e.g. in terms of a Material Transfer Agreement

A disclosure of an actual or intended benefit sharing arrangement by attaching either a signed BSA or a draft or proposed BSA

Permission from the landlord to conduct bioprospecting in the disclosed prospecting area.

The applicant must disclose, accurately and in good faith, all pertinent information based on its current best knowledge. PIC is limited to conferring access rights. PIC does not by default confer rights to use (e.g. to conduct research or commercialize) the genetic resource so accessed.

Benefit sharing

The purpose of a benefit sharing agreement (BSA) is to deal with the sharing, in a fair and equitable way, of the results of research conducted on, and the benefits arising from, the commercial, and other, utilization of a genetic resource. The party receiving the benefits should be either the entity providing access to the genetic resources (e.g. the state) or an entity, group, or individual, which need not be associated with the genetic resource but which must be endorsed by the state (e.g. a local indigenous community or a university).

As PIC is a precondition to a BSA, and if the entity granting PIC differs from the beneficiary party to the BSA, then the applicant:

Could enter into a BSA with an appropriate party, making PIC a condition precedent to the coming into force of the BSA and including, in the application for PIC, a copy of the BSA, or

Include in the PIC application a copy of a draft BSA which would be concluded if PIC were to be obtained.

If the entity granting PIC and the beneficiary party to the BSA are the same, the PIC terms and the BSA terms can be included in a single document, i.e. an access and benefit sharing agreement (ABS).

A difficulty with the abovementioned proposal is that there is no guarantee that the beneficiary party would conclude the proposed BSA with the applicant.

A BSA should also deal with the following general principles of the CBD:

Access to and transfer of technology which is relevant to the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity (Articles 16 (1) and 16 (2))

Exchange of information resulting from relevant research (Article 17 (2))

Technical and scientific cooperation in the fields of conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity and assistance in developing and supporting national capabilities in this regard (Article 18)

Access to the results and benefits arising from biotechnologies based upon genetic resources (Article 19 (2)).

South African law as it relates to bioprospecting

South Africa has been very progressive in including, into local law, the obligations of the CBD and principles espoused by the Bonn Guidelines. South African legislation that has codified these obligations and principles include the National Environmental Management Act 1998 (Act No. 107 of 1998), the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act 2004 (Act No. 10 of 2004), and the Patent Act No. 57 of 1978.

As a consequence of Act No. 10 of 2004, the Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) has been designated as an FP.

Persons involved in bioprospecting in South Africa have a legally prescribed point of reference to which issues regarding PIC and BSA can be addressed.

The South African Patent Act

To give effect to the principles of the CBD with respect to PIC and benefit sharing, the Patent Act No. 57 of 1978 has been amended to include in the filing requirements of a patent application, the obligation to file a statement (Form P26) declaring whether or not the invention for which patent protection is sought is based on indigenous knowledge.

A patent application will not be accepted for grant if the Form P26 is not filed.

If the Form P26 is filed, acknowledging that the invention is based on or derived from our indigenous biological resource, then the following must be lodged therewith:

A copy of the permit issued by the FP evidencing PIC

Proof of a material transfer agreement

Proof of a benefit-sharing agreement

Proof of co-ownership of the invention for which protection is claimed.

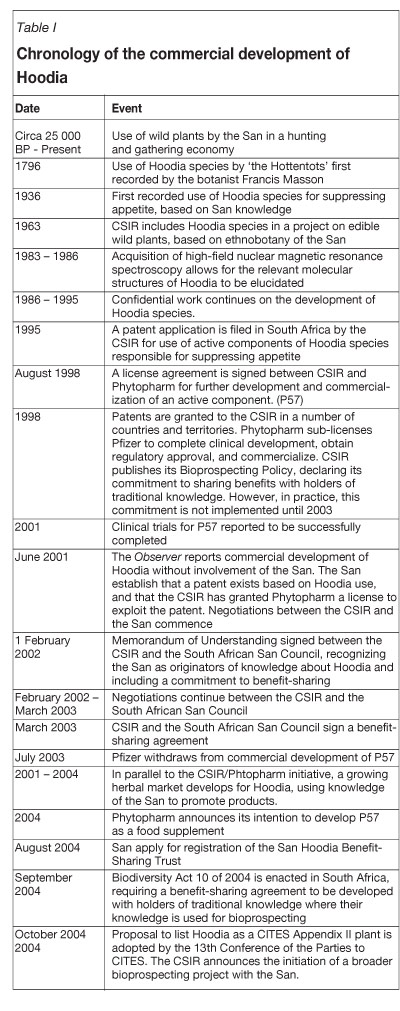

A South African example of access and benefit sharing

The following example of bioprospecting and access and benefit sharing in operation does not deal with a microorganism, but with the discovery and commercialization of extracts from the Hoodia plant. The general principles that can be gleaned from this example will, however, generally hold true in the area of micro-organism bioprospecting (Table I).

Conclusion

There still exists, within the field of percolation leaching, potential for generating intellectual capital based on patents. Due to a general lack of appreciation of this potential, many novel and inventive developments fall within the public domain but are not the subject matter of a patent application. As mentioned, a patent does not give to the patentee a right to exploit. It does, however, keep third parties at bay and allow the patentee to exclusively benefit from the invention, subject to third-party rights in the prior-art technology on which the invention is based. Without a patent, the patentee does not have a potential negotiating tool, should one be needed, to negotiate with a third-party right holder in a licence or benefit sharing type arrangement.

When it comes to the patenting of micro-organisms generally, a number of additional legal pre-conditions have to be met. These pre-conditions include, in the bioprospecting or discovery phase, the twin obligations of prior informed consent and benefit sharing and, in the patent application phase, a deposit with a pre-defined depository. Only when these pre-conditions have been met can the patent application be filed and the criteria of novelty and inventiveness examined.

What is often misunderstood is that, in patenting a micro-organism, you are not claiming ownership of a specific piece of life; you are claim exclusive rights to use the microorganism in a particular application, for example percolation leaching.

Using the Hoodia example, CSIR did not lay claim to Hoodia the plant but to an extract or active compound found in Hoodia that suppresses the appetite. The San, as a community, would be considered right-holders in the priorart technology i.e. the traditional knowledge that directed the CSIR to look to Hoodia for a solution to appetite suppression. The patentee, i.e. CSIR, borrowing on this knowledge, identified the active compound of the plant, and patented this compound. The patent capitalized this knowledge, which could be exploited, and ultimately was exploited, for mutual benefit.

References

AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE. Manual of Practice and Procedure. Section 2.9.2.14. http://wwww.ipaustralia.gov.au/pdfs/patentsmanual/WebHelp/Patent_Examiners _Manual.htm [Accessed 29 September 2012] [ Links ].

BONN GUIDELINES www.cbd.int/abs/bonn [ Links ]

CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY. http://www.cbd.int/convention/text [ Links ]

DEW, D., STEYN, J., and MINNAAR, S. 2009. High temperature leaching process. US patent 2011023662. [ Links ]

EMMETT, R. and O'CONNOR, L. 1990. Bioleaching apparatus and system. US patent 4,968,008. [ Links ]

SUGIO, T., MIURA, A., PARADA, V., and BADILAN, O.B. 2006. Bacteria strain wenelen DSM 16786, used said bacteria for leaching of ores and concentrates containing metallic sulfide mineral species and leaching processes based on the use of said bacteria or mixtures that contain said bacteria. US patent 7,601,530. [ Links ]

VAN BUUREN, C. 2005. Method of and apparatus for simulating a biological heap leaching process. US patent 7,727,510. [ Links ]

© The Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 2012. ISSN2225-6253. This paper was first presented at the Percolation Leaching Conference, 8-9 November 2011, Misty Hills, Muldersdrift.