Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy

On-line version ISSN 2411-9717

Print version ISSN 2225-6253

J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. vol.111 n.7 Johannesburg Jul. 2011

TRANSACTION PAPER

Mining fiscal environment in the SADC: status after harmonization attempts

H.D. Mtegha; O. Oshokoya

School of Mining Engineering, University of the Witwatersrand

ABSTRACT

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) aims to harmonize mineral policies and regulatory regimes in the minerals sector. This paper provides a review of the progress made towards harmonization of mineral regimes in the region. It singles out only the mining fiscal environment, as this is normally one of the key issues of interest to potential investors as well as the host state. Indications are that the region is slowly progressing towards a more harmonized approach, and there is evidence that the 'race to the bottom' has been prevented, which is the basis for an integrated mineral sector that the region aspires to.

Keywords: Harmonization, regional integration, competitive investment framework, benchmarking, fiscal environment.

Introduction

In 2004 the Southern African Development Community (SADC) started the process of harmonizing mineral policies and regulatory frameworks. The aim was to reduce differences in the operating environment between the member countries of the region. In this way:

➤ Regional integration would be enhanced

➤ The 'race to the bottom' would be avoided by the removal of competitive behaviour through the provision of incentives that are less beneficial to Member States

➤ By comparing and benchmarking against a competitive investment framework (CIF), the region would become more competitive.

Twelve mainland SADC countries were studied and data compiled for recommendations on a regional approach to harmonization. Nine areas of harmonization were identified, namely:

➤ Mineral policies

➤ Political, economic and social environmen

➤ General investment environment

➤ Mining fiscal environment

- International tax issues

- National tax issues

- Local government/regional tax issues

➤ Minerals administration and development systems

- Beneficiation, minerals marketing, cluster development, environmental management and participation in management of mining enterprises

➤ Artisanal and small scale mining

➤ Research and development

➤ Human resources and skills development

➤ Gender

This paper concentrates on the mining fiscal environment as one of the areas of prime interest to the investment community. An extract of recommendations from the approved SADC approach is discussed, together with changes in provisions. The paper examines progress to date and identifies region-specific issues when benchmarked with the Competitive Investment Framework (CIF). The contribution of these region-specific issues to new developments in the region's minerals sector is also discussed.

The framework and use

The mining industry is global, and the SADC mining sector is an integral part of and operates within this community. However, a critical tenet of globalization and its highly competititve environment is that capital flows towards more attractive destinations. If the SADC wishes to attract this capital, it must be competitive in relation to the more attractive destinations, while mitigating attempts by its Member States to compete against each other. With this in mind, a CIF was used as a benchmark for the region to both measure its global competitiveness and define its aspirational objectives. The CIF, which was developed by Cawood (1999) and applied in the development of a national mineral policy for the government of Malawi. The exercise incorporated a comparison with similarly endowed developing countries of Chile, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and China using set criteria. This was used as a basis for a harmonized framework aimed to attracting investment and competing globally, while at the same time fulfilling the desire for regional integration without 'racing towards the bottom'.

The CIF may be used to benchmark in two ways:

➤ Member State can respectively work towards individual compliance with the standards proposed by the CIF. Should all countries be similarly motivated and guided by the same standards they will eventually converge towards a common set legal provisions

➤ Utilize a SADC range of country actions and provisions to compare the region as a whole to the CIF and request the SADC to make the necessary adjustments as a block.

The responses of individual states moving towards the CIF was recognized in respect of the following differences in:

➤ mining tradition, where some countries have more established industries than others

➤ minerals and specific commodities endowment levels of infrastructure necessary for mineral development, among others.

Progress towards harmonization

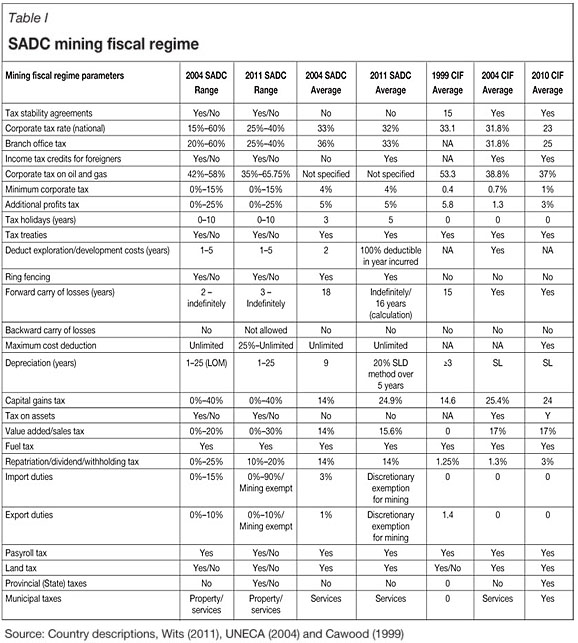

Table I shows data for the SADC as compiled in 2004 (UNECA, 2004) and updated in 2011 (University of the Witwatersrand, 2011). Data also include CIF calculated for 1999, 2004, and 2010 so that global trends can be ascertained.

Member States trends

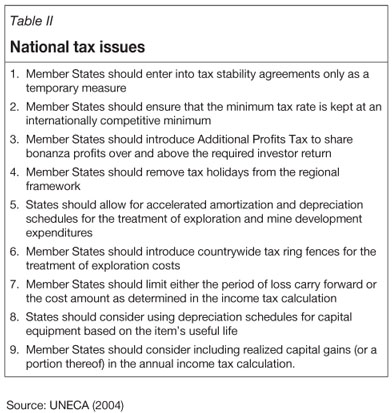

The trends for Member States may be observed from SADC Ranges for 2004 and 2011 as shown in the second and third columns of Table I. The 2004 data shows the starting point, the situation as it existed at the harmonization initiative, and the 2011 data shows the current status. Tax stability arrangements have remained consistent over the two periods under review. Some Member States retain these while others do not have them. Table II shows a summary of specific recommendations in a number of issues or instruments. Item 1 in Table II recommended eventual elimination of this provision.

The corporate tax range has narrowed from 2004 to 2011. In 2004, the range was wide, from a low of 15 per cent to a high of 60 per cent, while in 2011 the minimum was 25 per cent and the high 40 per cent. This demonstrates positive signs of progress towards harmonization of mineral tax regimes. This is in turn a positive development for potential investors to the region. Branch office tax also narrowed during the period with the low rising from 20 per cent in 2004 to 25 per cent in 2011. Similarly, there was a reduction from a high of 60 per cent to 40 per cent. This reflects progress towards harmonization.

Income tax credits for investors have remained nearly the same. Minimum corporate tax levels have remained the same among the Member States, reflecting the need for all to maintain incomes. Additional Profits Tax (APT) has also remained within the range of zero to 25 per cent. In the wake of a general public outcry that mining companies get the lion's share of resource rents compared to the government's portion, the maintenance of APT is not surprising. This view is not specific to the SADC. The introduction of APT in the SADC was recommended to Member States as shown in in item 3 of Table II.

Tax holidays have remained within the same range of zero to 10 years. This is a reflection of the need to attract investment to obtain the perceived benefits from mineral development, even though it was recommended that tax holidays should be abolished (item 4 of Table II). Tax treaties have similarly remained the same. It is expected that nearly all of the SADC Member Status will subscribe to this provision in the interest of dealing with double taxation issues over time.

Deducting exploration and development costs have become standard practice and from no basis for competition between Member States. Ring fencing has also remained in place during the period and will likely continue the same to protect sources of tax from operating mines.

Forward carry of losses has remained the same, with indefinite periods allowing companies to recover losses from future cash flows. Even though this practice (indefinite) is not recommended, as item 7 in Table II shows, presumably this is also an effort to attract investment. In the case of backward carry of losses, Member States have maintained provisions of not using this.

In the same vein, maximum cost deduction has remained and depreciation has remained within the range from 1 to 25 years or life of mine. Capital gains tax and tax on assets have remained with the same range. Value added tax has increased in range from zero to 20 per cent to 30 per cent at the upper end. This is inconsistent with the 'race to the bottom' hypothesis, and indicates a firm resolve to bolster minerals-related fiscal flows to Member States. Fuel taxes reflect similar trends.

Repatriation, dividends, and withholding tax range has changed from a low of zero per cent to 25 per cent to a minimum of 10 per cent and a maximum of 20 per cent. This has created a new source of income for more countries, but has capped at 20 per cent instead of 25 per cent. Again, this is a reflection of the need to increase government share from resource development while at the same time not reflecting the 'race to the bottom' by converging the range.

Import and export duties have been almost entirely removed or exempted in the case of mining. These are important cost containment items for investment and production. Payroll taxes, land taxes, and municipal taxes are payable in all Member States. Provincial (state) taxes are not the norm in the region and are therefore not an area of concern.

These observations reflect a progressive harmonized approach towards the instruments of the mining fiscal regime in the SADC. The observations do not reflect competition between Member States in attracting investment to the sector. All tend to show a desire to attract investment with similar levels of fiscal instruments, while at the same time extracting fiscal benefits for social and economic development.

While SADC Member States are looking at ways of increasing revenues and providing an attractive investment climate, across the region the people at grass roots level are calling for greater tangible benefits to accrue to them. Issues are changing. In 2004, tangible benefits were not an issue. Governments are responding to people's cry for these benefits. In implementing democratic principles, people are driving or setting the mineral resources agenda for social and economic development. These demands are increasingly being addressed in various forms by Member States through empowerment provisions, state mining companies, state participation, and indigenization. This effort is expected to gain momentum as the industry's prospects continue to brighten. This will tend to reduce focus on other aspects of the fiscal regime.

Regional trends

Table I shows regional trends as SADC averages for 2004 and 2011. Most of the provisions remain relatively consistent for 2004 and 2011. Significant changes include the following:

➤ Corporate tax rate which has reduced from 33 per cent to 32 per cent. This is in line with global tendencies to reduce such taxes. Branch office tax level has also decreased from 36 per cent to 33 per cent. These trends bode well for attracting investment

➤ Capital gains tax that seems to have averaged higher at 25 per cent from 14 per cent even though the range remained the same at zero to 40 per cent

➤ Import and export duties, which appear to have been removed by all Member States with discretionary exemption for mining. This is in line with standard practice to minimize mining costs

➤ Value added tax has increased from 14 per cent to 15.6 per cent, inching towards a global average.

The regional trends tend to show certain provisions with the aim of attracting investments by reducing taxes and costs where appropriate, as well as increasing revenues where feasible. The net provisions as reflected in the SADC averages are contrasted with the CIF to examine competitiveness and identify areas requiring attention.

Competitive investment climate (CIF)

The last three columns of Table I show the CIF for three years. The first year (1999) was derived by Cawood (1999). The 2004 and 2010 CIF were derived by the application of Cawood's framework. A number of observations can be made:

➤ Tax stability agreements are standard in CIF, and therefore an area where the SADC is still not wholly compliant

➤ The CIF corporate tax rate has declined continuously from 33.1 per cent in 1999 to 23 per cent in 2010 compared with the SADC's 33 per cent. Some downward adjustment may therefore need consideration

➤ CIF branch office tax has come down from 32 per cent to 25 per cent, as compared to the region's 33 per cent. Some action may be considered here

➤ Minimum CIF corporate tax hovers around 1 per cent, whereas in the SADC it is around 4 per cent. Action may be recommended

➤ The CIF additional profits tax averages 3 per cent, while the SADC rate stands at 5 per cent. Considering emotions about benefit sharing in the SADC, it is unlikely that this rate will come down in the near future

➤ CIF repatriation, dividend, and withholding tax is around 2 per cent, while the SADC rate is at a high of 14 per cent. This is an area where the region may also wish to make necessary adjustments.

In most other areas it is evident that the SADC has moved towards CIF, and would therefore be poised to be globally competitive if some of the issues referred to above were addressed. It must be borne in mind that consideration here has not been taken of changes, if any, in mineral administration and development systems. These would go hand-inhand when considering the overall evaluation of harmonization and work that still needs to be done. Suffice to note that in May 2009, an Ad hoc Expert Group Meeting (UNECA, 2009) of officials from the 12 SADC mainland Member States convened to discuss harmonization of national mining policies in the region. This paper will not comment on the progress of that meeting, but the observation of the participants on the harmonization agenda is pertinent here. It is significant, however, that officials at this meeting highlighted the inadequate capacity of the SADC Secretariat to drive the harmonization agenda. The implications of this are serious in that, without opportunities where Member States could periodically share and compare information and ideas and agree on common strategies and plans, harmonization would slow or falter. This aspect cannot be overemphasized as it could place the entire harmonization agenda in the minerals sector of the SADC under threat.

Conclusion

In general, progress towards harmonization seems to have been made in a number of areas. Compared with the CIF as set out, the SADC region has:

i. Moved towards the CIF in a coordinated effort for the region to become more competitive

ii. Moved towards adopting a harmonized approach and in so doing directly contributing to or enhancing regional integration

iii. Mitigated tendencies towards competitive behaviour and 'racing towards the bottom'

iv. Has not changed in areas deemed essential for the region.

However, for the SADC not to be static in being guided by the benchmark set in 2004, the CIF needs to be dynamic and be reworked periodically as circumstances change. Such decisions are strategic and must be considered as such. As the thrust is focused on attracting investment and developing common approaches, the dynamic nature of the sector also calls for Member States to act in response to citizens' calls. These calls will vary from country to country and Member States' responses will also vary depending upon their unique situations. Such decisions will invariably have an impact on regional issues.

References

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). Harmonisation of Mining Policies, Standards, Legislative and Regulatory Frameworks in Southern Africa. 2004. [ Links ]

University of the Witwatersrand, School of Mining Engineering. Southern African Country Reports. 2001. (Internal document) [ Links ]

CAWOOD, F.T. Determining the Optimal Rent for South African Mineral Resources. PhD thesis, School of Mining Engineering, The University of the Witwatersrand. 1999. [ Links ]

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, (UNECA). Report of the Ad hoc Expert Group Meeting on the Harmonisation of Mining Policies in the SADC Subregion. 2009. [ Links ] ◆

Paper received Jul. 2011