Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

African Entomology

On-line version ISSN 2224-8854

Print version ISSN 1021-3589

AE vol.30 Pretoria 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2254-8854/2022/a10696

SHORT COMMUNICATION

Southern African vernacular names of Solifugae (Arachnida) and their meanings

Tharina L BirdI, II; Lefang L ChoboloIII; Audrey NdabaIV

IGeneral Entomology, DITSONG National Museum of Natural History, Pretoria, South Africa

IIDepartment of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Hatfield, South Africa

IIIDepartment of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Botswana International University of Science and Technology (BIUST), Palapye, Botswana

IVNatural Science Collections Facility (NSCF), Brummeria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The order Solifugae (Arachnida) often has the word 'spider' (e.g. sunspider, camelspider) or 'scorpion' (e.g. windscorpion) as the main descriptor in its common names. Being neither a spider nor a scorpion, we suggest 'solifuge', derived from the scientific name of the order, as the most neutral English vernacular name for these arachnids. Southern Africa is rich in solifuge diversity, which is also reflected in the rich and imaginative local vernacular names of this group. These names allude to myths associated with solifuges, to their characteristic behaviours, or to their unique and striking morphology. Here we briefly translate and discuss 40 vernacular terms used for solifuges in 25 languages and dialects in southern Africa (Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe), plus seven names in five languages in East Africa. Recognising solifuges as a distinct group, referred to by its own set of vernacular names, seem to be more common in rural, compared to urban areas. The conservation of indigenous names of animals might be inextricably linked to the conservation of these animals.

Keywords: biodiversity; camelspider; conservation; indigenous; urbanisation

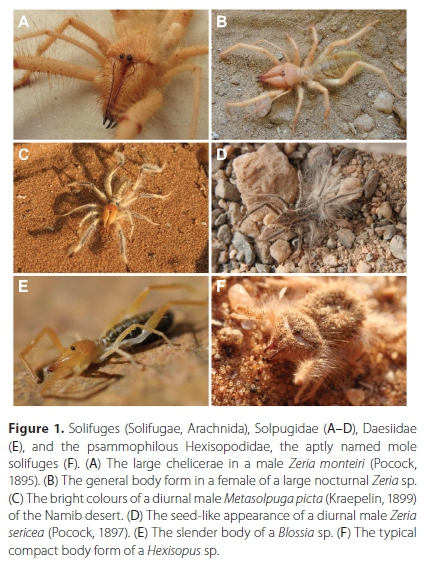

Solifuges are enigmatic arachnids that belong to the order Solifugae (Figure 1, photos A-F). Often confused with spiders, they can be distinguished from other arachnids by the pair of formidable two-segmented scissor-like chelicerae (Figure 1, photo A), and the presence of malleoli, which are sensory organs situated ventrally on legs IV. Solifuges are further distinguished from spiders by the lack of spinnerets, and the absence of a pedicel that marks a clear division between the prosoma and the opisthosoma (Figure 1, photo B). Solifuges are completely harmless to humans. They do not produce any venom, and only the largest specimens could break the skin of a human when they bite. The latter does not happen often given their great speed and manoeuvrability, which does not allow sustained contact with humans.

Just over 1100 solifuge species are recognized globally (Bird et al. 2015: 21). Africa has the highest diversity, with nine of the 12 families occurring on the continent. The largest degrees of species and family level endemicity is found in southern Africa (e.g. Lawrence 1963; Dippenaar-Schoeman et al. 2006). This richness is threatened by habitat destruction, caused by inter alia large-scale mining and urban sprawl. For more effective conservation of solifuges, research is needed on this group (taxonomy, ecology, distribution, etc.), while greater efforts need to be made to raise public awareness of their existence.

The most neutral - i.e. not invoking spiders or scorpions - vernacular name for these arachnids is 'solifuge', which is derived from the scientific name of the order. Various other English vernacular names are also used. Globalization tends to create uniformity, even in English vernacular names. The reference 'camelspider' refers to the hump-shape that is prominent on the prosoma of some species (Punzo 1998). 'Camelspider' was popularized globally through tales, often of great imagination, by American soldiers stationed in the Middle East (Oswald 2012). This resulted in 'camelspider' being used increasingly globally, even in southern Africa (e.g. Neethling & Haddad 2019). Common English vernacular names used traditionally in southern Africa are sunspider, red roman, or roman. In some of the local languages, colourful names were coined for solifuges. Unfortunately, solifuges have a largely cryptic behaviour, and as urbanization has increased, fewer people are aware of their existence. As a result, these local names are threatened with extinction. Here we document words used for solifuges in local languages in southern Africa (Table 1).

Words were gathered through various means. Some words were provided to the first author (T. Bird) by communities themselves, or representatives of the communities (East African words, and the G|ui, G||ana, Hai||o, Ju|'hoan (previously !Kung), and Khwe-dam Khoisan words). Some words were provided by biologists (i.e. Afrikaans, Damara, German, Oshiwambo, Otjiherero, Setswana, chiShona, and isiZulu). The remainder of the names were gathered by asking colleagues from different language groups and countries, either based on a variety of photos of solifuges sent via WhatsApp, or, where possible, showing random persons a preserved solifuge specimen. Only names that could be verified (e.g. through crosschecking, or where there was reason to believe that the names were correct, such as a description that made sense) were included. All efforts were made to check the spelling, but the correct spelling could not be guaranteed. We are aware of the debates around the 'Khoi' and 'San' languages (e.g. du Plessis 2019), but here we only present the information communicated to us, and how that information was conveyed to us by indigenous language speakers. We do not claim to provide a comprehensive list of words used for solifuges in southern Africa, but we hope to i) stimulate awareness of solifuges, and ii) form the basis of documentation of various words used to describe solifuges in different languages and dialects in different regions in southern Africa and in Africa at large.

Some names refer to solifuge taxa, or particular groups of solifuges, instead of solifuges as an Order. The family Hexisopodidae is a unique group of psammophilous solifuges, adapted to spending most of their lives in the sand, and these are aptly named mol solifuges (mole solifuges) (Figure 1F). The Afrikaans word rooiman, corrupted to rooi roman, or romans, was initially coined in the Eastern Cape for the red species living in the Karoo (Lawrence 1967). Later, across South Africa and Namibia, it became common to use these terms to refer mainly to the large, nocturnal Zeria spp. (Solpugidae) (Figs. 1A, B). Holm & Dippenaar-Schoeman (2010) refer to all solifuges as romans. In the language of the Kalanga people of Botswana, the name hibababa, which is said to refer to the large solifuges, might also refer only to large nocturnal Zeria spp. Most words, however, refer to solifuges as a group.

The words Solifugae, or 'solifuge' mean flee from the sun (sol = sun; fugae = flee), referring to the majority of species that are nocturnal. However, in Africa, and indeed southern Africa, there is a relative high number of diurnal species (Figure 1, photos C & D), which comprise spectacular forms with bright colours, including reddish orange, sulphur yellows, and whites often contrasted against charcoal black. These diurnal species are active during peak day temperatures, which resulted in the popular name used for solifuges: sunspiders (sonspinnekoppe in Afrikaans). The theme of sun in the local languages in South Africa is also found in the isiZulu (ilanga, meaning sun), Sesotho (maletsatsi, meaning 'mother of the sun') and isiNdebele (isbadwa, also meaning 'mother of the sun') languages. It is not clear whether these words were in existence prior to the arrival of European settlers. The isiZulu word bhora mkantsha ('burrowing into the bone marrow') is also interesting in that the word bhora is borrowed from the English word burrow. Borrowed words are common in African languages, and in this case it indicates that the word originated relative recently, probably after the arrival of the British in Africa (1820s).

The main reason why solifuges are cryptic is the way in which they move, which means that the human mind does not always register them. However, the way that solifuges are moving is also highly typical, and is a characteristic that might be predominant for a keen observer. Apart from being able to run at extreme speeds when disturbed, their movements are erratic, changing direction suddenly in a zigzag manner (Wharton 1987), often punctuated with sudden stops. Indeed, the movement of most solifuges - the burrowing solifuges of the family Hexisopodidae (Figure 1, photo F) are an exception - is so characteristic, that one only needs to mimic the movement of a solifuge with one's arm, to often elicit immediate recognition of a solifuge in local communities in which there is otherwise a language barrier.

It is therefore not surprising that the movement of solifuges is commonly used as a name descriptor.

Most indigenous names in southern Africa describe their behaviour, in particular their fast, erratic, seemingly directionless movement (dzwatshwatswa in Kalanga, and the similar dvatsvatsva in chiShona, otjimbiryangauri in Otjiherero, n\hava\ava in Khoisan (Khwe-dam), selaalii and mmalebelwana in Setswana), or the effect that their way of movement can have (e.g. break up a gathering around the fire as seen in the Oshiwambo word eyambaula-hungi; or wake up the elderly from their sleep, as seen in the chiShona word chimutsavakuru). Use of the apt reference Kalahari Ferrari seemed to remain restricted to a relatively small geographic area. This term, probably coined by Afrikaans speaking Namibian farmers of the Kalahari, only recently gained popularity through social media, although locals in Namibia mentioned that they knew about this reference already by the late 1990s.

Another behavioural characteristic is captured in the Afrikaans word vetvreter, alluding to their ability to gorge themselves until the intersegmental membranes of their opisthosoma is stretched to the full. Yet another Afrikaans name, jaagspinnekop, refers to the behaviour of diurnal solifuges. Being active during the absolute heat of the day, the diurnal solifuges that are relatively common in southern Africa take resting periods in the shade as a behavioural adaptation against overheating. The word jaagspinnekop seems to stem from that behaviour, where they might attempt to take refuge in the shadow cast by a person, and then to follow the shadow as the person moves away, creating the impression that they are being chased. The same behaviour could be seen with a solifuge chasing a shadow thrown by a light at night. A corruption of the word, with time, resulted in jaag (chase) becoming jag (hunting), resulting in jagspinnekop.

An association between scorpions and solifuges is captured in the names used by the Tshwa Khoisan in Botswana (in the word tsatamqãa) and two possible dialects of the Ju|'hoani Khoisan (previously known as !Kung) in Namibia (in the words \konta\inand tutugaberespectively). It is indeed known amongst arachnologists who work on scorpions and solifuges that nights that are optimal for scorpion activity are usually also optimal for solifuge activity. Another factor that could further contribute to a perceived correlation between scorpions and solifuges is the fact that scorpions - and most likely solifuges, although this has not scientifically been investigated yet - are largely active during low moonlight intensity (e.g. new moon, before moon rise and after moon set) as a predator avoidance mechanism. The combination of greater scorpion activity, together with the fact that solifuges are attracted to light, including light from fires that would be visible at greater distances during the darkness in the absence of moonlight, and therefore attract solifuges from greater distances, most likely explains these names.

Names that allude to myths associated with solifuges are also common. For example, the Afrikaans words haarskeerder (haircutter), or baardskeerder (beardcutter), are interesting in this regard. One origin is the myth that solifuges would cut their way out of a female's hair when tangled in it. Another origin stems from reports of bald spots, where hair was cut close to the skin in both persons and animals while asleep, with the blame attributed to solifuges, who were believed to use the hair to line their nests (Dippenaar-Schoeman 1993; Holm & Dippenaar-Schoeman 2010). The claim has not yet been experimentally substantiated. There is photographic documentation of a solifuge removing the feathers of a young dead bird by cutting it close to the skin, before starting to feed on the brain of the bird (Holm & Dippenaar-Schoeman 2010). In South Africa, a town called Baardskeerdersbos (34°35'20"S, 19°34'15"E), in the Western Cape, provides homage to this local name.

Some myths, as reflected in the words, are probably instilled by the fierce-looking nature, and large chelicerae of solifuges (Figure 1, photo A) (e.g. looking for a man's private parts to bite as seen in the Khoisan (Hai||om) word tgarareb; or the myth that it bites girls as seen in the Sekgalagadi word serababasezana; or burrowing into the bone to feed on bone marrow as per the isiZulu word bhora mkantsha).

An interesting myth in the Zulu culture is that solifuges can bring luck. Their ability to run fast and change direction with ease is seen as possessing some supernatural power. It is thus not unusual to see people jump over a solifuge asking for luck. "Bhora mkantsha ngicela inhlanhla" ("Solifuge, can I have luck") will be repeated as many times as the solifuge is visible, or while it is still in the vicinity.

In some languages (e.g. Chichewa in Malawi, Khoisan (G|ui; G||ana) in Botswana, Tshivenda in South Africa), the name has no particular meaning that could be traced, and the word seems to stand on its own, in other words, it is a word unique to solifuges. This was also the case for the two words, gint and sherevit, used for solifuges in the ancient Ethiopian Amharic languages. The Kalanga and chiShona words dzwatshwatswa and dvatsvatsva respectively, and the Khoisan (+Aonin, or 'Topnaar') word \Gomtsi Xharebeb also seemed reserved for solifuges, although these still have a meaning in that it describes the "restless movement" of solifuges. In Damara we could not find a dedicated word for solifuges, and the word for spider is used. The word for spider also seemed to be commonly used in other languages (isswebu in isiNdebele; isigcawu in isiXhosa), even though a word for solifuges exists in isiNdebele (isbadwa), while isiXhosa speakers sometimes make reference to the Afrikaans word roman (uRomani; or isigcawu esingu Romani). Whereas in Botswana at least two words for solifuges exist in Setswana, in South Africa it seemed that the word 'spider' (sekgokgo) is the only word used.

Some words provided to us indicate that persons were not familiar with solifuges, but rather confused various arthropods. Examples ofwords that were sent to us and referred to as solifuges, included selomabasetlha in Serolong, which refers to tampans; majuru in chiShona, which refers to alate termites; and phepheng in Setswana, which refers to small scorpion species. Anecdotal observations indicated that unfamiliarity with solifuges was especially strong in urban areas. In Kenya and Ethiopia for example, local communities seemed to recognize solifuges, sometimes only a description thereof, without hesitation, and with an associated local name in all the languages, for example, seb in Arbore, sari or orbobabis in Borana, toko in Hamer. A similar recognition was not found in the cities in these countries. In Somaliland, too, it was only informants from rural areas, and interestingly two entomologists that were interviewed, who recognized solifuges as animals that are distinct from spiders (latter called caaro in Somali). Given the importance of camels in Somalia and Somaliland, the phrase used for solifuges, oday geelii baay (old man looking for his lost camel), is fitting. This trend was also seen in South Africa - many persons living in the Gauteng urban and even semi-rural areas did not recognize a solifuge from a specimen. However, some did recognize the name in their language when we mentioned it. One respondent from Zimbabwe was elated to put the name with the animal that her grandmother always referred to. Conserving indigenous names might be inextricably linked to conserving the animals. This is not a new concept, and the link between biodiversity and language has been highlighted before (e.g. Gorenflo et al. 2012).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Benson Muramba and Hermine Inana for providing the first words from Namibia. We thank colleagues in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa who assisted in sending out WhatsApp messages and who asked their colleagues and family members for words, namely Telané Greyling, Elna Irish, Sifelani Jirah, Annemarie Loots, Phumzile Mahlangu, Noel Malangano, Unathi Mani, Smith Moeti, Ellen Mwenesongole, Vusi Ndala, Tedson Nkoana, Casper Nyamukondiwa, and Diane Patrick Rapelang. Ansie Dippenaar-Schoeman provided haarskeerder and baardskeerder information. Sandra Naude kindly checked the near-final manuscript for English editing, and Motsane Getrude Seabela checked the manuscript for general ethnographic terminology; both made valuable suggestions. Most of all, we are greatly indebted to those that responded to our requests and to the persons and communities who shared their words and stories with us for documentation.

ORCID IDs

Tharina L Bird - https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4409-8866

Lefang L Chobolo - https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2496-3496

Audrey Ndaba - https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3218-2641

REFERENCES

Bird TL, Wharton RA, Prendini L. 2015. Cheliceral morphology in Solifugae (Arachnida): primary homology, terminology, and character survey. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 394: 1-355. https://doi.org/10.1206/916.1 [ Links ]

Dippenaar-Schoeman AS, González Reyes AX, Harvey M. 2006. A check-list of the Solifugae (sun-spiders) of South Africa (Arachnida, Solifugae). African Plant Protection 12: 70-92.

Dippenaar-Schoeman AS. 1993. Sun-spiders, some interesting facts. African Wildlife 47: 120-122. [ Links ]

Du Plessis M. 2019. The Khoisan languages of southern Africa: facts, theories and confusions. Critical Arts 33(4-5): 33-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2019.1647256 [ Links ]

Gorenflo LJ, Romaine S, Mittermeier RA, Walker-Painemilla K. 2012. Co-occurrence of linguistic and biological diversity in biodiversity hotspots and high biodiversity wilderness areas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(21): 8032-8037. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117511109 [ Links ]

Holm E, Dippenaar-Schoeman AS. 2010. GOGGAgids. Die Geleedpotiges van Suider-Afrika. 1st Edition. Lapa Uitgewers, Pretoria.

Lawrence RF. 1963. The Solifugae of South West Africa. Cimbebasia 8: 1-28. [ Links ]

Lawrence RF. 1967. The life of the sun-spider. African Wild Life. 10-16. [ Links ]

Neethling JA, Haddad CR. 2019. Influence of some abiotic factors on the activity patterns of trapdoor spiders, scorpions and camel spiders in a central South African grassland. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 74(2): 107-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0035919X.2019.1596177 [ Links ]

Oswald JM. 2012. Know thy enemy. Camel spider stories among US troops in the Middle East. In: Eliason EA, Tuleja T. (Eds). Warrior Ways: Explorations in Modern Military Folklore. University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.7330/9780874219043.c02

Punzo F. 1998. The Biology of Camel Spiders (Arachnida, Solifugae). 1st Edition. Kluwer Academic, Boston. 301 pp.

Wharton RA. 1987. Biology of the diurnal Metasolpuga picta (Kraepelin) Solifugae, Solpugidae) compared with that of nocturnal species. Journal of Arachnology 14: 363-383. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Tharina L Bird

Email:tharina@ditsong.org.za

Received: 10 April 2021

Accepted: 21 July 2021