Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Enology and Viticulture

On-line version ISSN 2224-7904

Print version ISSN 0253-939X

S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. vol.41 n.2 Stellenbosch 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.21548/41-2-4224

ARTICLES

Is There a Link Between Coffee Aroma and the Level of Furanmethanethiol (FMT) in Pinotage Wines?

G. Garrido-Bañuelos#; A. Buica*

South African Grape and Wine Research Institute, Department of Viticulture and Oenology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland 7062, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Over the years, Pinotage has found its way into the South African and international market. Producers have used the flavour potential of this "original" South African grape to produce different wine styles, one of them being the so-called "coffee-style Pinotage". The current study aims to explain the impact of furanmethanethiol (FMT) on the characteristic coffee aroma of these coffee-style wines. Chemical and sensory evaluation, as well as data mining of the technical information available, was performed. Not all wines marketed as "coffee Pinotage" showed a high "coffee" rating. However, the results showed a good correlation between the aroma perception and FMT concentrations (R2 = 0.81). However, RV coefficients were low when comparing the coffee rating with the information provided on both the front and the back label, which shows that, in some cases, the use of the "coffee Pinotage" term was rather part of the marketing strategy.

Keywords: Pinotage, red wine, furanmethanethiol, thiols, sensory evaluation, multifactorial analysis (MFA)

INTRODUCTION

Innovation and product development are key to the success of any industry. Any changes introduced during processing can alter the physicochemical properties of a product and consequently influence its sensory space. In winemaking, different vineyard management techniques, as well as the use of different winemaking techniques, can modulate the aroma (Ruiz et al., 2019), taste and mouthfeel of a wine (Smith et al., 2015). Although the global wine industry has always been associated with tradition, it continuously seeks to explore new markets, as well as to implement new technologies to ensure better control of the winemaking process.

Wine aroma is one of the main drivers of the identity of a wine. The smell of a wine is the result of series of synergistic and masking interactions between aroma compounds and the non-volatile compounds in the wine matrix (Ferreira et al., 2015; Garrido-Bañuelos et al., 2020; McKay & Buica, 2020). These molecules are like the different characters in a book: individually they can be associated with specific features, but when interacting they can build a story. In short, the aroma of a wine can help us to detect not only the wine faults (Chatonnet et al., 2004; Mayr et al., 2015), but also to identify the grape cultivar, region, country or even some of the winemaking techniques employed in the process (Ferreira, 2010). Some of these compounds are strongly associated with certain wines, such as rotundone and the black pepper smell in Australian Shiraz (Siebert et al., 2008), and the presence of certain lactones in dessert wines (Stamatopoulos et al., 2015). Some of these compounds can be considered quality drivers for wines (Brand et al., 2020).

Similarly, the coffee aroma in wines has been associated with specific molecules, such as 2-furanmethanethiol (FMT) in Bordeaux wines (Tominaga et al., 2000). Despite certain furan derivatives being converted into alcohols with coffeelike notes by the yeast, this aroma is generally linked to the wine ageing in oak barrels and the size and level of toasting of the wood pieces (Fourie, 2005; Fernández de Simón et al., 2010).

The understanding of the odorant impact of FMT is of special interest for the South African wine industry. Pinotage is the "original" South African grape of excellence, but achieving an understanding of its flavour potential and acceptance in specific markets is an ongoing pursuit (Vannevel, 2015). Pinotage can be produced in different styles, and the so-called "coffee style Pinotage" is well known. Traditional Pinotage-style wine displays notes of 'chocolate box', 'banana', 'fruity', 'tobacco' and 'toasty', whereas the coffee-style wines have notes of 'chocolate box', 'banana', 'smoky', 'burnt rubber' and 'roast coffee bean' (Marais & Jolly, 2004; Naudé & Rohwer, 2013). The volatile fingerprint of Pinotage wines has not been investigated widely (Weldegergis et al., 2011), but the combination of furan and 2-furanmethanol and its role in the perception of the coffee aroma have been demonstrated by comparing traditional Pinotage to coffee-style Pinotage (Naudé & Rohwer, 2013). FMT and 2-furanmethanol have a similar chemical structure, where an S atom in the former (a thiol) replaces the O atom in the latter (an alcohol). Both compounds are found in roasted coffee and exhibit its particular aroma (pubchem.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov). The presence of FMT was not found in Pinotage wines by Naudé and Rohwer (2013), but a more recent study has shown that the levels of this thiol in Pinotage wines can range between 0.9 and 186 ng/L (Mafata et al., 2018).

The present study investigated the correlation between the levels of FMT and the perception of the "coffee" aroma in some South African Pinotage wines from both the traditional and coffee styles. In addition, the information available on the labels and in technical notes was evaluated to see how accurate it is in relation to this wine style.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Wines and sensory evaluation

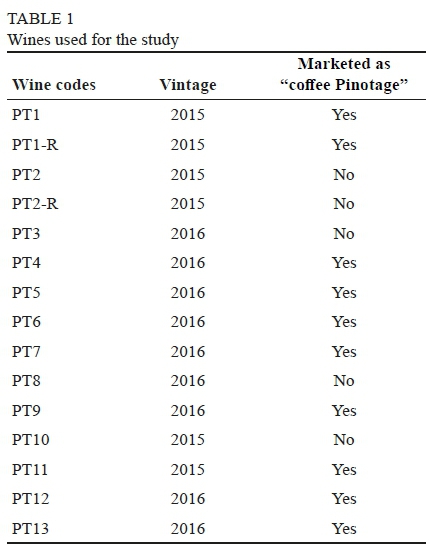

The study took place early in 2018. A total of thirteen wines, all commercially available, were selected for the study (Table 1). Nine out of the thirteen wines were marketed as "coffee Pinotage" by using images and descriptors on the front and back labels related to coffee, mocha and/or chocolate. The following Pinotage wines were from the 2015 vintage: PT1, PT2, PT10 and PT 11; the rest of the selected wines were from 2016 vintage. All wines had an alcohol content of 13.5% to 14% according to the labels.

All wines were evaluated in duplicate by a total of 15 trained panellists from the analytical panel of the Department of Viticulture and Oenology of Stellenbosch University. The wines were presented in a randomised order, introducing two blind duplicates (PT1-R and PT2-R) according to a Williams Latin square design. The evaluation was performed under room-controlled conditions. The coffee aroma of the wines was rated on an unstructured linear scale (from 0, corresponding with no coffee aroma, to 100, corresponding with high coffee aroma). The experimental design and data capturing were done with Compusense cloud software (Compusense Inc, Guelph, ON, Canada).

Thiol analysis

Thiol analysis was performed for all the wines according to the method of Mafata et al. (2018). The main interest of this work was to assess the relationship between FMT and coffee aroma, but the levels of 3MH, 3MHA and 4MMP were also quantified. Sample preparation was done by derivatising the thiol moiety (-SH) of 3MH, 3MHA, 4MMP and FMT with 4,4'-dithiodipyridine (DTDP). Sample purification was based on a solid-phase extraction on an SPE-ENVI-C18 cartridge (Supelco, Bellefonte, USA), followed by analysis by UPC2-MS/MS (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA) on a BEH C18 column (Waters Corporation). Detailed information regarding the derivatisation, sample preparation and chromatographic conditions are as described in Mafata et al. (2018).

Label information

Graphic or text references to coffee were obtained from the front and back labels of the selected wines. If the labels did not include aroma profiles, descriptors were extracted from the technical notes provided on the producers' sites.

Statistical analysis

The sensory results were analysed with a two-way ANOVA (including the judge as a random factor and the wine as fixed factor) and post-hoc Tukey's test with STATISTICA 13 (Palo Alto, CA, USA). The results obtained on thiol content were analysed with a one-way ANOVA. Multifactorial analysis (MFA) was performed between the text data based on the frequency of citation of the different descriptors found on the wines labels. Text data was separated into three categories. First, front label, for which a data matrix was made on a binary base. A value of 1 was given to the wines that at least made reference to 'coffee/mocha/chocolate' on the front label, whereas a value of 0 was assigned to wine with no mention of these attributes. Back label data were split into two categories: coffee-related attributes (coffee, mocha and chocolate) and other descriptors (rest of attributes displayed on the back label of all selected wines). Other descriptors found on the wine labels were 'berry', 'fruity', 'fruitcake', 'raspberry', 'cranberries', 'spicy', 'plum', 'cinnamon', 'cherry', 'mulberry', 'prune', 'oak', 'Turkish delight', 'nuts', 'rooibos' and 'honeybush'. A data matrix for the sensory results was included as intensity values. The RV coefficient obtained from MFA was used to compare the configuration of the distribution of the wines according to the different variables.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Rating results

The rating task was considered of medium difficulty by the judges. Fig. 1 illustrates the results of the one-way ANOVA on the rating results. The repeatability of the two blind duplicates was excellent (PT1 vs PT1-R and PT2 vs PT2-R, Fig. 1). The rating of the coffee aroma of the wines was therefore found to be a discriminant variable between the products. The ANOVA analysis showed that the PT9 wine was perceived as having the highest coffee aroma intensity on the nose (average 70.03 out of 100), followed by PT4 and PT6. However, the coffee aroma in PT4 and PT6 were not significantly higher than in PT5 (Fig. 1). Despite ten (nine plus blind duplicate) of the total wines being marketed as "coffee" Pinotage, the rest of the wines showed relatively lower and not statistically different intensities in the coffee aroma. Also, no significant differences were found between the Pinotage wines not marketed as "coffee" Pinotage (PT2, PT3, PT8 and PT10) and some of those that were.

Chemistry results and correlation with sensory results

The concentrations of the four thiols are given in Table 2. The level of FMT covered a wide range, from 6 ng/L to 138 ng/L; three wines stood out through their very high level of this compound, namely PT9, PT4 and PT6 (133 ng/L to 138 ng/L FMT), while most of the wines were in the range of 20 ng/L to 40 ng/L, and none were in the mid-range. Considering the concentration ranges of the other thiols, the wines were not very different from each other. All thiols were present above their odour thresholds, of 60, 4.2, 0.8 and 0.4 ng/L for 3MH, 3MHA, 4MMP and FMT, respectively (Mafata et al., 2018).

A good correlation was found between the level of FMT and the rating of the wines (R2 = 0.81). This finding was indicative of a good correlation between the thiol concentration and the sensory perception - better than previously found for other single thiols in complex matrices (Garrido-Bañuelos et al., 2020). This possibly was due to the particular aroma imparted by this thiol to the wine, or to the Pinotage matrix, or a combination of both. Fig. 2 illustrates the relationship between the concentration of FMT and the intensity of the coffee aroma perceived in the wines. It can be observed that the three wines that showed the highest intensity of coffee aroma had the highest levels of FMT. It can also be noted that some wines with a lower FMT concentration were perceived to have a more intense coffee aroma than some with higher FMT concentrations, such as PT5 compared to PT13. In fact, PT5 (marketed as coffee style) had a lower level of FMT than some non-coffee Pinotage wines, but a higher perceived intensity of the aroma, indicating that the interaction of FMT with other compounds could have had an influence on the perception.

The next step was to explore the possible role of the other measured thiols (3-MH, 3-MHA and 4-MMP) in the perception of the coffee aroma. A recent study has shown that the interaction between 3-MH and 4-MMP in dearomatised red wine matrices results in "herbaceous, buttery and coffee aromas", with high levels of 3MH (Garrido-Bañuelos et al., 2020), but the interaction with FMT was not explored. In the current study, 3-MH was found to be the major thiol in all wines, with the exception of PT4. A good correlation was not found between the levels of 3-MH and the coffee smell (R2 = 0.04). However, a good negative correlation was found between the percentage of total thiols represented by 3-MH and the rating of the coffee smell (R2 = 0.85). In other words, the lower the percentage of 3-MH, the higher the perception of coffee aroma. Two of the wines with the highest concentration of 3-MH (PT8 and PT3) were perceived to have the lowest intensity of coffee smell. However, wines such as PT4 and PT9, with a high level of 3-MH, were perceived to have a high intensity of coffee aroma; this could simply be attributed to their levels of FMT. In the previously cited work (Garrido-Bañuelos et al., 2020), the authors did not find any particular attribute associated with the presence of 3-MH in red wines. On the other hand, FMT has a prominent coffee smell and, as shown in this work, the high levels of FMT correlated with a high perception of coffee aroma.

Correlation with label descriptors

An MFA was performed to establish the relationships between the configuration of the wines according to the information offered on the front and back labels and the rating of the coffee aroma perceived by the panel. The explained variance of the MFA map for the first two factors was 47.35%. On the score plot in Fig. 3, the wines not marketed as coffee style can be observed on the left side of the horizontal axis, opposite to most of the coffee-style samples. This also corresponds (on the loadings plot) to the configuration of the rating and the usage of coffee-related descriptors on the front and back labels, where 'coffee', 'mocha' and 'chocolate' were considered as sensory attributes linked to the coffee style. When considering the data blocks, the highest RV coefficients (Table 3) were found between the coffee-related descriptors on the front label and the coffee rating (0.42); however, this is a low RV value. The RV coefficient of the data block of coffee-related attributes on the back label vs the coffee rating from the sensory evaluation was even lower (0.20). This could be explained by the presence of other attributes to describe the wines on the back label; the similarity in the configuration from the MFA (including all blocks) and the block containing the "other descriptors" was the highest (RV 0.727).

CONCLUSIONS

The study has shown a clear relationship between the levels of FMT and the perception of coffee aroma in South African coffee-style Pinotage wines. However, not all the wines marketed in this way are either perceived to have a coffee aroma or are chemically characterised by higher levels of FMT. This shows that some of the wines marketed as coffee-style Pinotage would be perceived as such; however, in some cases, it appears to be more of a marketing strategy.

LITERATURE CITED

Brand, J., Panzeri, V. & Buica, A., 2020. Wine quality drivers: A case study on South African Chenin blanc and Pinotage wines. Foods 1-17. [ Links ]

Chatonnet, P., Bonnet, S., Boutou, S. & Labadie, M.D., 2004. Identification and responsibility of 2,4,6-tribromoanisole in musty, corked odors in wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52(5), 1255-1262. [ Links ]

Fernández de Simón, B., Cadahía, E., Álamo, M. & Nevares, I., 2010. Effect of size, seasoning and toasting in the volatile compounds in toasted oak wood and in a red wine treated with them. Anal. Chim. Acta 660, 211-220. [ Links ]

Ferreira, V., 2010. Volatile aroma compounds and wine sensory attributes. Manag. Wine Qual. 3-28. [ Links ]

Ferreira, V., Sáenz-Navajas, M.-P.P., Campo, E., Herrero, P., de la Fuente, A. & Fernández-Zurbano, P., 2015. Sensory interactions between six common aroma vectors explain four main red wine aroma nuances. Food Chem. 199, 447-456. [ Links ]

Fourie, B.A., 2005. The influence of different barrels and oak derived products on the colour evolution and quality of red wines. MSc. thesis, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, 7602 Matieland (Stellenbosch), South Africa. [ Links ]

Garrido-Bañuelos, G., Panzeri, V., Brand, J. & Buica, A., 2020. Evaluation of sensory effects of thiols in red wines by projective mapping using multifactorial analysis and correspondence analysis. J. Sens. Stud. 35(4), 1-11. [ Links ]

Mafata, M., Stander, M., Thomachot, B. & Buica, A., 2018. Measuring thiols in single cultivar South African red wines using 4,4-dithiodipyridine (DTDP) derivatization and ultraperformance convergence chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Foods 7(9), 138. [ Links ]

Marais, J. & Jolly, N., 2004. Pinotage aroma wheel. WineLand 113-114. [ Links ]

Mayr, C.M., Capone, D.L., Pardon, K.H., Black, C.A., Pomeroy, D. & Francis, I.L., 2015. Quantitative analysis by GC-MS/MS of 18 aroma compounds related to oxidative off-flavor in wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63(13), 3394-3401. [ Links ]

McKay, M. & Buica, A., 2020. Factors influencing olfactory perception of selected off-flavour-causing compounds in red wine - A review. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 41(1), 56-71. [ Links ]

Naudé, Y. & Rohwer, E.R., 2013. Investigating the coffee flavour in South African Pinotage wine using novel offline olfactometry and comprehensive gas chromatography with time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1271(1), 176-180. [ Links ]

Ruiz, J., Kiene, F., Belda, I., Fracassetti, D., Marquina, D., Navascués, E., Calderón, F., Benito, A., Rauhut, D., Santos, A. & Benito, S., 2019. Effects on varietal aromas during wine making: A review of the impact of varietal aromas on the flavor of wine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103(18), 74257450. [ Links ]

Siebert, T.E., Wood, C., Elsey, G.M. & Pollnitz, A.P., 2008. Determination of rotundone, the pepper aroma impact compound, in grapes and wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 3745-3748. [ Links ]

Smith, P.A., McRae, J.M. & Bindon, K.A., 2015. Impact of winemaking practices on the concentration and composition of tannins in red wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 21, 601-614. [ Links ]

Stamatopoulos, P., Frérot, E. & Darriet, P., 2015. Evidence for perceptual interaction phenomena to interpret typical nuances of "overripe" fruity aroma in Bordeaux dessert wines. ACS Symp. Series 1191, 87-101. [ Links ]

Tominaga, T., Blanchard, L., Darriet, P. & Dubourdieu, D., 2000. A powerful aromatic volatile thiol, 2-furanmethanethiol, exhibiting roast coffee aroma in wines made from several Vitis vinifera grape varieties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48(5), 1799-1802. [ Links ]

Vannevel, M., 2015. Marketing wines to South African Millennials: The effect of expert opinions on the perceived quality of Pinotage wines. MSc thesis, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, 7602 Matieland (Stellenbosch), South Africa. [ Links ]

Weldegergis, B.T., De Villiers, A. & Crouch, A.M., 2011. Chemometric investigation of the volatile content of young South African wines. Food Chem. 128(4), 1100-1109. [ Links ]

Submitted for publication: July 2020

Accepted for publication: August 2020

* Corresponding author: E-mail address: abuica@sun.ac.za

# Current affiliation: Product Design, RISE Research Institutes of Sweden - Agrifood and Bioscience, Box 5401, S-402 29, Gõteborg, Sweden

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Winetech for funding this research study