Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

On-line version ISSN 2224-7890

Print version ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.33 n.3 Pretoria Nov. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7166/33-3-2793

SPECIAL EDITION

Using action research to determine the systematic application of international best practice methods and standards in managing risk in event management

G.S. JonesI,*; S. NaidooII

IGraduate School of Business Leadership, University of South Africa, South Africa

IIDepartment of Operations Management, University of South Africa, South Africa

ABSTRACT

All business involves assuming and managing risk, and this is particularly true of businesses involved in the staging and management of events, which are inherently risky endeavours. Event management is thus intrinsically concerned with managing various forms of risk. This study aims to identify the factors that influence best practices in managing risk during event management, and to determine the extent to which the factors contribute towards effectively managing risk in event management. More than ever before, a variety of stakeholders are expecting that event organisers will actively engage in managing risks and will do so to the extent of what can be considered reasonably practicable. A qualitative approach was undertaken for this study, consisting of ten online (virtual) semi-structured interviews with selected experienced professionals to ascertain their perspectives on managing risk in events management, and why best practice standards are often not employed. The study concluded that risk management must be an integral part of the event management process, encompassing all phases of events.

OPSOMMING

Alle besigheid behels die aanvaarding en bestuur van risiko, veral waar besighede betrokke is by die aanbieding en bestuur van gebeure wat inherent riskant is. Gebeurtenisbestuur is dus intrinsiek gemoeid met die bestuur van verskeie vorme van risiko. Hierdie studie het ten doel om die faktore te identifiseer wat die beste praktyke in die bestuur van risiko tydens gebeurtenisbestuur beïnvloed en om te bepaal tot watter mate die faktore bydra tot die effektiewe bestuur van risiko in gebeurtenisbestuur. Meer as ooit tevore verwag 'n verskeidenheid belanghebbendes dat organiseerders van geleenthede aktief betrokke sal raak by die bestuur van risikos en dit sal doen in die mate van wat redelikerwys as uitvoerbaar beskou kan word. 'n Kwalitatiewe benadering is vir hierdie studie onderneem wat bestaan uit tien aanlyn (virtuele) semi-gestruktureerde onderhoude met geselekteerde ervare professionele persone om hul perspektiewe oor die bestuur van risiko in gebeurtenisbestuur vas te stel en waarom beste praktykstandaarde dikwels nie gebruik word nie. Die studie het tot die gevolgtrekking gekom dat risikobestuur 'n integrale deel van die gebeurtenisbestuursproses moet wees wat alle fases van gebeurtenisse insluit.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the short term, major events have the potential to provide value and to benefit a wide range of stakeholders. For example, the Two Oceans Marathon was estimated in 2016 to contribute R672 million to the economy of the Western Cape and Cape Town every year. Events, especially those of a significant magnitude such as the Olympic Games or World Cup tournaments, can have a lasting legacy impact on the host venue [1]. Events are also inherently risky endeavours. Uncontrollable factors such as security can have significant consequences for events and compromise their feasibility and profitability [2].

Although risk is central to the management of events, and thus managing risk is a critical component of event management, there is no single commonly accepted set of standards and practices that is employed to manage risk holistically at events. Owing to the impact that events can have on host economies, many major events attract public funding, and this creates a scenario in which there are a variety of stakeholders, often with competing or non-aligned agendas, and this makes decision-making, which is at the heart of all risk management, cumbersome and difficult [3]. Different stakeholders have different appetites for and approaches to risk [15] and differing objectives and desired outcomes that affect decision-making and risk planning activities. Where an event organiser might focus their risk management activities on reducing business risk and liability, a sponsor would likely be more concerned with reputational risk management.

In the South African context, the challenge is that, while there are many very useful and beneficial standards and systems to be used, there is no prescribed and specific set of standards for licensing authorities to apply; rather, applicable standards such as building regulations are used at the discretion of the official in question [20]. So, rather than having a system of standards, instead we have a morass of confusing and conflicting information that does not result in the improved management of risk in real terms, nor does it improve working practices, nor does it increase accountability or improve the standards of the industry.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, all events, many of which were cancelled or postponed because of the health risk posed by mass gatherings, have to be planned with the management of a specific risk, such as public health and the spread of COVID-19, at the very heart of every endeavour [5]. The impact of these cancellations is significant for a variety of stakeholders. It has been estimated that the cancellation of just four major annual sporting events staged in South Africa would see R1.2 billion lost, and would lead to an increase in unemployment and poverty in the country [6].

1.1. The research problem

Although events are important despite being inherently risky, standardised, formalised methodologies related to risk management are not generally observed, or are observed only to satisfy minimum levels of compliance [4].

The regulatory confusion and lack of standardised practices, combined with the devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, make for an environment that is likely to deter participation by a variety of stakeholders unless it can be demonstrated that risk can be adequately managed. This limits the opportunities for events to be staged, and thus limits the opportunities for event organisers generally. As such, research into event risk management methodology is relevant and necessary at this time. Therefore, the research problem for this study was to identify the perceived factors that influence international best practice methods and standards in managing risk in event management.

1.1.1. Research questions

1. What are the factors that influence best practices in managing risk during event management?

2. What is the impact of the identified factors that influence best practices in managing risk during event management?

3. What recommendations can be made to enhance best practices in managing risk during event management?

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Managing risk is central to the process of managing events, and all aspects of event management decision-making must relate back to various forms of risk. Indeed, many sporting and entertainment events specifically rely on risky endeavours as a central attraction for their audiences, such as motor racing and stunt performances [5].

In order to identify the factors that impact and influence best practices for managing risk at events, and to create recommendations for best practices at events, it is necessary to identify the types and dimensions of the risks faced by events, and to identify typical event stakeholders and how each type of stakeholder might be the most or the least affected by the various forms of risk. Thereafter, we must look, the phases of events, and the process of risk management, as well as the role of the risk manager in events.

2.1. Conceptual framework

Risk is defined as uncertain future occurrences that, if left unchecked, could adversely influence the achievement of a company's business objectives [8].

Too much emphasis can be placed on event managers by the managers of their organisation to achieve trade-offs between safety concerns and financial considerations, leading to increased risk and thus creating disasters caused by the organisation itself [8], which could also be reasonably categorised as an event risk management 'own goal'. The best way for an event organiser to develop appropriate plans, and to be able to demonstrate that this has been done according to the most reasonable and appropriate standards, is by applying a widely recognised and accepted best practice that takes into account the absolutely necessary requirements of an event without giving undue consideration to other factors [4].

Duty of care is an important consideration for event organisers in the context of risk. It is well defined by [9]:

Duty of care is a legal principle that regards the event organiser as a responsible person who must take all reasonable care to avoid acts of omissions that could injure another. It means taking actions that will prevent any foreseeable hazard of injury to the people who are directly involved, or affected by the event: staff, volunteers, performers, audience, host community....

Failure to honour one's duty of care results in liability that is judged for its severity by the degree of negligence, as shown in Figure 2:

Not upholding one's duty of care can have serious implications for event organisers, leading to civil claims of liability and criminal penalties in certain cases. The Event Act [20]specifies that organisers may face criminal prosecution for failing to plan and run an event according to the requirements of the Act, with penalties of up to 20 years in prison being specifically stated. This is a significant incentive for event organisers to be able to demonstrate that they have taken the utmost care to keep risks to the lowest reasonable level.

2.2. The need for standards

2.2.1. Defining 'standards'

Standards are defined as a document established by consensus and approved by a recognised body that provides, for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines, or characteristics for activities or for their results, aimed at achieving the optimum degree or order in a given context [10]. 2.3.2 Inherent risk

Gathering large groups of people together for any reason results in risk [11], and different types of groups of people, or crowds, will present different kinds of risks in different circumstances [4]. While each event is unique, it cannot be denied that following standards, wherever possible, and deviating from these standards only for good, well-thought-out reasons rather than for issues relating to time and money, will always be a better approach. Following widely accepted standards and practices for events allows the event organiser not only to be compliant with local authorities, such as permit and licensing bodies, but also to manage risk proactively [9].

2.2.2. Liability

Event organisers must also consider the possibility of an incident occurring for which they could face civil and/or criminal legal action; and being able to demonstrate that they took all reasonable and necessary precautions to avoid the incident would be of value to the organiser.

The standards set for many aspects of events have proven effective and necessary [12], and deviation from them has resulted in disaster. Perhaps the best known such disaster occurred at the Hillsborough Stadium in the UK in 1989, when 96 people were killed when the viewing terraces collapsed. They were later shown to have been loaded well beyond their capacity as dictated by the UK's Guide to Safety at Sports Grounds, also known as the Green Guide [13].

2.2.3. Unique but similar

Large gatherings of people happen all the time, and generally do so without incident. However, a mix of insufficient or deficient facilities, combined with flawed crowd management practices, may well lead to death or injury. To reduce uncertainty and to create a standard set of operating procedures, processes should be formalised that are appropriate to the territory and environment in which the event takes place [9].

2.2.4. Templates, frameworks, and standardisation

In the Green Guide and the Purple Guide, which defines similar criteria for music festivals and other similar events there are a great many templates and frameworks specific to events for elements such as risk assessments. Having templates for event-specific fire risk assessments, food safety assessments, evacuation requirements assessments, and so on allows for standardisation, meaning that organisers and their personnel, as well as licensing authorities, can evaluate information that is presented in a standardised and consistent way that is most appropriate to each event [14].

2.2.5. Accurate predictions

Using an established international standard allows an organiser reasonably to predict such things as the maximum number of spectators and thus the number of tickets that could be sold for an event, which is critical when conducting a feasibility analysis and the initial planning [14].

2.2.6. Scenario planning for decision-making

An additional benefit of using standardised templates, from a risk management point of view, is that it can make the task of what-if analysis and scenario planning simpler and more effective. While scenario planning cannot fully anticipate all possible scenarios [14], it allows the organiser and other role players and stakeholders the opportunity to plan for a variety of scenarios, thereby automating certain decisions, which would allow for greater levels of training and preparation of event personnel.

2.2.7. Crowd management variables

Each event is unique and comprises a unique set of variables that must be carefully considered [9]. The operations of the event must be crafted to reflect and accommodate the variables, as they might be difficult to quantify, and an assessment must be done, especially for each event, based on its own unique mix of variables. For example, a crowd of angry political protesters at a rally should be treated and planned for differently than a crowd of bird-watching aficionados at an exhibition, even if the crowd numbers and venue are similar.

2.2.8. Compliance vs risk management

A major concern is that organisers and other stakeholders confuse managing compliance with actually managing risk. An organiser might find themselves to be compliant on paper, at least enough to obtain the necessary paperwork to proceed with the event; but they could be negligent in real terms and face legal claims and/or the loss of insurance protection and coverage in the event of an incident [13].

2.2.9. Setting standards internally

The event organiser's harshest critic, from a risk management point of view, should be themselves, and the standard for risk management should be set internally rather than on external standards, which might or might not be sufficient to offer true protection from risk. Risk management in the context of events can sometimes be seen as an add-on to be undertaken after the event has already been conceptualised, designed, and planned [13], but this is both unrealistic and impractical. For risk management to be truly effective, it needs to form part of every phase of the event [4].

2.3. The risk management process

Risk management (defined as the purposeful recognition of and reaction to uncertainties with the explicit objective to minimise liabilities and maximise opportunities using a structured approach and common sense) [4] cannot be conducted once, approved, and forgotten about, which is what a compliance-based approach often yields; rather, risk management must be seen as continuous and be applied deliberately, consistently, dynamically, and effectively throughout the various phases of the event [4].

The benefits of following a defined and deliberate process, and the negative consequences of not doing so, are listed below:

Risk planning is defined as "providing the structure for making decisions based on realistic assumptions and accepted methods" [4] The objective of risk planning is to ensure that decisions affecting risk are based on rational suppositions using commonly accepted methodologies, and incorporating both lessons learned from previous projects and international best practices [4].

2.4. Dimensions of risk, and typical event-specific risks

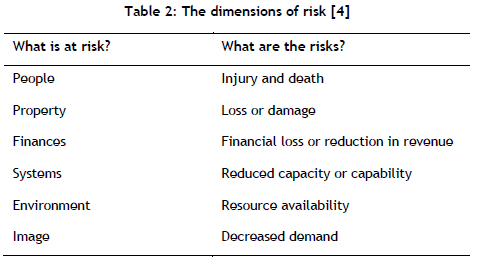

The dimensions of risk, in the context of events, are presented below in Table 2 [4].

The dimensions of risk show clearly that risk at events is not a simple matter of health and safety. Gathering large groups of people together for any reason results in risk [11], and different types of groups of people, or crowds, will present different kinds of risks in different circumstances. Silvers and O'Toole [4] also state the typical event risk factors quite clearly (Table 3).

These typical event risk factors are extensive, and would form a solid basis for an event risk assessment.

2.5. Stakeholders

A stakeholder can be described as any person or entity that has some sort of stake or investment in an event, and the roles that they assume are often multiple in nature or vary according to the phase of the event [15]. Some stakeholders are actively involved in the project, while others are able to impose control or influence over the project.

2.5.1. Stakeholder theory

The demands of stakeholders have a direct impact on the way companies operate, and thus affect their economic performance [16]. As such, consideration of the demands that stakeholders will likely have, and the motivations for these demands, are important for any company to consider. Stakeholders can be categorised as internal, external, regulatory, value chain, and public [16]. Regulatory stakeholders have the authority and legal standing to affect the operations of the event organiser negatively, not only through the non-issuance of permits but also through penalties and other restrictions [16]; therefore, event organisers must consider the requirements of these stakeholders very carefully.

2.5.2. The role of the risk manager

Organisational risks owing to an unclear structure of authority or unsanctioned decision-making are significant threats to events [4]. A stakeholder might be very valuable to an event, but that does not necessarily give them the right to make decisions about the operation of the event.

To avoid organisational risks such as this, it is imperative that organisers spell out clearly, in the form of written plans and organisational charts, who is responsible for what, and ensure that all personnel are briefed accordingly.

Overall, a risk manager should be appointed for the event. This person could be the overall event organiser, or they could be a separate individual; in the latter case, the relative levels of responsibility and authority of each must be specified upfront [15].

2.6. Event phases

Figure 3 demonstrates the event management phases [4].

• Initiation - This is when a commitment to risk management must be instituted. Initial conceptualisation and research are conducted, and the project scope is established. Resources are identified, evaluated, and selected, and objectives are set.

• Planning - Specifications of requirements for elements such as the procurement of services are created, plans for the deployment of resources are drawn up, activities are planned and programmed, and risk planning and the decision-making considerations specific to the event take place.

• Implementation - Service providers are appointed, and the coordination of all logistical and operational elements takes place. Risk management techniques are required during this phase to ensure the proper verification and control activities are employed" [4].

• The event - This is when the event itself begins, as opposed to the implementation phase when the event site is being made ready. In this phase, the dynamic process of meeting the health and safety requirements for workers and visitors is conducted at the same time as the production.

• Closure - This involves shutting down the event site and physically dismantling and removing all event-related goods, equipment, and services.

The phases of the EMBOK model (Figure 3) show that, in the phases preceding the actual event, there are a number of go or no-go decisions that might have to be made. At any stage, if the risks involved are deemed to be too high, the project might have to be called off, and a no-go decision should be made. Decisions should be considered against prescribed or previously defined criteria to be evaluated at particular pre-determined milestones. This demonstrates how risk management must be continuous throughout the various phases of a project, and cannot simply consist of a plan prepared in advance and forgotten about once approved.

2.7. Research findings from literature review

The literature review revealed that events are inherently risky, and thus the event organiser has a duty of care to ensure that all stakeholders are appropriately considered. It was also revealed that there are various types of risk, all of which have unique considerations and must be carefully evaluated and managed before or during the event phases in which the risks are most likely to be encountered. Further findings included that the event organiser should focus on setting internal standards based on established best practices, which would be preferable to relying on standards imposed by external sources when seeking to minimise risk; and that the role of the risk manager is critical to managing risk effectively.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1. The research onion

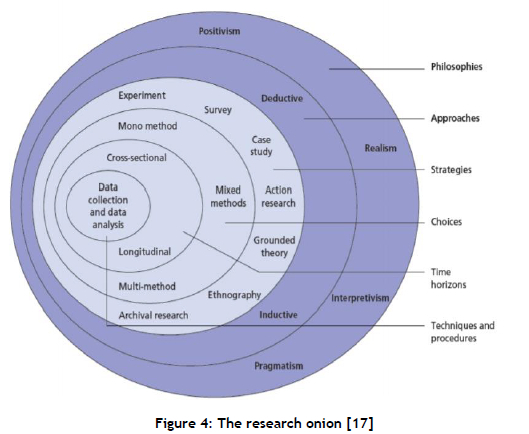

This research project took the approach described below, starting with the outside layer of the 'research onion' (Figure 4) and working inwards:

• The philosophy that was followed was that of interpretivism. This study examined the feelings, beliefs, and opinions of our interview participants. The issue itself was known - for example, that the use of standardised approaches and best practice methods in the field of risk management as it relates to events is low. We sought to discover why this is, and how it might be improved.

• The approach of the survey was to be inductive rather than deductive because, rather than testing a specific hypothesis to prove an existing theory, the purpose of this study was to understand the reasoning and context of the respondents. So a small sample was selected rather than a large sample, as might have been the case with a deductive approach.

• The strategy employed was that of action research. By interviewing people in various positions who were directly involved with managing risk in the context of live events, the study sought to understand why the adoption of best practices was not widely prevalent.

• The mono method was chosen in the case of this study, and specifically in-depth exploratory interviews with selected subjects.

• The time horizon was cross-sectional, owing to the constraints of the research project. The interviews were conducted by looking at the risk management practices of industry professionals at the time of their interviews.

• The techniques and procedures used for data collection and analysis were semi-structured, face-to-face, and online (virtual), in that all of the interviewees were asked the same set of questions, which were open-ended and designed to invite opinion that required analysis rather than specific, easily quantifiable binary or set-scale answers.

3.2. Research roadmap

The reason for choosing to use qualitative data was to gauge the opinions and lived experiences of the participants with regard to the prevailing standards and practices of event risk management in South Africa. As a result of this more intensive method of study, the sample size had to be smaller, and the analysis was drawn primarily from thoughts and opinions rather than numerical data [18]. As the industry in South Africa is relatively small - and is becoming ever smaller in the wake of COVID-19, which made most major events impossible - a smaller sample size was appropriate. Commonalities were sought, themes and sub-themes were identified and categorised, and a thematic map was created.

3.3. Qualitative research approach

The purpose of this study was to identify the factors that influenced best practices in the context of live event management, and to provide recommendations about how these might be adopted. To understand this, it was necessary to engage with people who were actively employed in the field and were responsible for managing risk at events, either as event organisers themselves or as consultants or advisors to event organisers. To understand the how of the issue, it was necessary to obtain the opinions and beliefs that were born of first-hand experience.

3.3.1. Population and sample

The target group for this study was industry professionals who were experienced in managing events or acting as safety or risk management consultants to event managers and who had significant experience in managing events and/or their risk aspects in South Africa. A total of ten purposively and conveniently sampled participants were chosen for the study.

3.3.2. Qualitative data collection method

The semi-structured online (virtual) interviews were based on pre-determined questions that were common to every interviewee, and were supplied to each participant in advance for review. The interviews featured open-ended queries that were aimed at extracting opinions and perspectives from the participants [19].

3.3.3. Qualitative data analysis

An exploratory study was undertaken in which a small sample was interviewed, and the data recorded from the discussion with each participant was assembled and analysed, with the opinions and beliefs being extrapolated.

3.4. Trustworthiness

3.4.1. Credibility

There was no incentive of any kind for participants to take part in the study, nor were there any inducements for providing any particular answer. The researcher asked all of the respondents exactly the same questions, and presented their answers as received without any variation or manipulation of the results.

3.4.2. Dependability

All of the interviews were recorded and transcribed thereafter to ensure their veracity. The transcripts of the interviews were sent to the research subjects to confirm their authenticity.

3.4.3. Conformability

The data would be stored electronically for a minimum period of five years, and was password-protected in a secure, cloud-based storage platform.

3.4.4. Transferability

The findings would be applicable and relevant to the practice of risk management in the field of live events, as they would provide insight into the reasons for the low levels of adoption of the standardised processes and practices that could reduce the risks for event organisers in real terms.

4. RESULTS AND FINDINGS

A review of the event management or risk management literature indicated clearly that international best practices reduce risk, and that the failure to adhere to specific standards can result in disaster; and yet these practices and standards are often ignored. To understand why this is the case, and to identify recommendations to event organisers to improve their risk-management practices, we had to gather and interpret qualitative data directly from industry role-players. Figure 6 shows the findings of the thematic analysis used in the study.

4.1. Summary of main theme 1 findings: Understanding the concepts in event management

Events are inherently risky, and have to be managed. Although there are requirements from licensing authorities and similar bodies to present risk management documents, submissions, and plans, these are often merely perfunctory exercises and are seldom checked for veracity or accuracy. As such, while there should be a link between compliance and risk management, in reality it is rather tenuous. Many organisers or service providers do follow best practices if they are required to by some other stakeholder, such as an insurer or an endorsing federation, but otherwise they might not make the effort. Events take place over specific phases, and the nature of the risk, and thus the approach that needs to be taken to manage it, changes over these phases.

4.2. Summary of main theme 2 findings: Internal factors that influence best practices in managing risk

The event organiser must do everything within their power to minimise those risks over which they have control, evaluate the internal risk, and ensure that the best interests of all parties are considered. By following best practices, the event organiser could minimise the potential effects of negative incidents that affect reputation, safety, or profitability. The event organiser has a responsibility to look after the interests and the safety of all stakeholders, but ultimately they must prioritise event attendees.

4.3. Summary of main theme 3 findings: External factors that influence best practices in managing risk

External sources and stakeholders can have a major impact on events, and can increase various forms of risk significantly. Establishing requirements from entities such as licensing authorities is critical when standards cannot be immediately ascertained. Major events can have a significant impact on communities, and for long-term success, it is important that these and other interested and affected parties are considered and that the event is properly managed. Environmental factors pose a significant safety risk to events, and thus adequate precautions must be taken to prevent disaster.

5. DISCUSSION

The research's conclusions are given for each research question, based on the findings defined in the research questions.

Question 1: What are the factors that influence best practices in managing risk during event management?

This question has been answered, in that the factors identified as enhancing best practices are as follows:

• Incorporating managing risk into every aspect and phase of managing events

• Clearly identifying the risk considerations, responsibilities, appetites, and attitudes of a variety of stakeholders

• Clearly defining the role of the risk manager or the various roles of risk management related to different event management roles within the project

Question 2: What is the impact of the identified factors that influence best practices in managing risk during event management?

The impacts of the identified factors are as follows:

• Reducing the exposure of the event organiser to claims of liability because self-imposed adherence to best practices, in addition to compliance with external standards, shows that all that is reasonably practicable has been done to ensure that all risks have been reduced as much as is reasonably possible.

• Understanding the risk-related implications and expectations of different stakeholders allows the event organiser to tailor risk planning towards those areas that are deemed most critical, thus having the greatest positive impact on the project.

Clearly defining the risk management roles, including that of the overall risk manager, empowers the person tasked with this responsibility to make the necessary decisions with as much knowledge and comprehension of the issues in question as possible. By defining a role and bestowing specific responsibility, the impact created is that a risk manager is able to make objective decisions without undue influence such as commercial pressures.

Question 3: What recommendations can be made to enhance best practices in managing risk during event management?

The recommendations that can be made are as follows:

• For the event organiser to set standards internally, based on widely accepted international best practices and best suited to the type of event in question, rather than relying on attaining a satisfactory standard set by external parties

• Documenting and distributing information and procedures related to managing risk during events to all relevant stakeholders as is appropriate to their level of involvement in the event

• Allowing for ample time and budget to address managing risk properly as part of the project planning process

6. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

Event organisers can reduce the liability they face, be it civil, criminal, or financial, by setting internal standards that are based on best practices, thereby signifying that they have made all reasonably practicable efforts to manage risk effectively to levels that are as low as is reasonably possible. The needs and risk profiles and the priorities of all stakeholders must be considered and addressed in order for event organisers to manage risk effectively in their projects.

7. CONCLUSION

Events are inherently risky, and, despite the tenuous link between being compliant with external standards and effective risk management, many event organisers focus on minimum compliance standards rather than on working towards international best practice standards. Event organisers have a responsibility and duty of care towards all stakeholders, especially event attendees, to manage risk effectively and to be seen to be doing so. The most effective way of achieving this, and of limiting their own liability and exposure to financial risk, is through the internal adoption of high standards that are linked to international best practices. The long-term viability of events in particular, and of the organisers who run them generally, is enhanced by the event organisers' willingness and ability to manage risk effectively, considering the needs and objectives of a wide variety of stakeholders. Establishing the requirements of external entities is essential to effective event management and to the governance of risk where no specific standards exist. Using an established standard with which one is compliant is preferable for event organisers, rather than relying on bespoke or arbitrary standards. Event organisers must plan for uncertainty and changing conditions, both environmental and regulatory; and making use of an established standard allows for this to be done to the greatest effect.

8. LIMITATIONS

The respondents might not have answered with absolute facts, and may have been misleading about their knowledge of certain aspects of the matters being discussed for the purposes of appearing more knowledgeable than they really were. Similarly, the respondents might have sought to impress and overstate their relative knowledge, awareness, and experience. In addition, the respondents were limited to those working in South Africa.

9. ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

• All source material was properly recognised and cited.

• All participants were assured of their privacy, their anonymity should it be requested, and confidentiality, and were informed in advance of the intended purpose and background of the study and its relevance.

• Personal data was kept private, and permission was obtained in express written form before any personal information was shared.

• All relevant University of South Africa ethics policies were strictly adhered to throughout the study.

• COVID-19 protocols were followed during all interviews that took place in person.

REFERENCES

[1] M. Robertson, F. Ong, L. Lockstone-Binney, & J. Ali-Knight, "Critical event studies: Issues and perspectives," Event Management, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 865-874, 2018. doi: 10.3727/152599518X15346132863193. [ Links ]

[2] H.G.T. Olya, "A call for weather condition revaluation in mega-events management," Current Issues in Tourism, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 16-20, 2019. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2017.1377160. [ Links ]

[3] K. Swart, & D. Maralack, "COVID-19 and the cancellation of the 2020 Two Oceans Marathon, Cape Town, South Africa," Sport in Society, vol. 23, no. 11, pp. 1736-1752, 2020. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2020.1805900. [ Links ]

[4] J.R. Silvers, & W. O'Toole, Risk management for events, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2021. [ Links ]

[5] J. Dahlström, "Finnish event organisers and strategic responses to COVID-19 crisis," Bachelor thesis, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences, Finland, 2020. [ Links ]

[6] I. Perold, C. Hattingh, H. Bama, N. Bergh & J.P. Bruwer 2020. 1 1ndependent Researcher, South Africa 2 Business Re-Solution, South Africa, www.businessresolution.co.za Last updated on May 2020. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3634508. [ Links ]

[7] R. Naidoo, Corporate governance: An essential guide for South African companies, 3rd ed. Durban: LexisNexis, 2016. [ Links ]

[8] M.T. Vendelo, "The past, present and future of event safety research," in A research agenda for event management, J. Armbrecht, E. Lundberg and T.D. Andersson, Eds. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019, ch. 3, pp. 23-34. doi: 10.4337/9781788114363.00010. [ Links ]

[9] P. Wynn-Moylan, Risk and hazard management for festivals and events. London: Routledge, 2017. doi: 10.4324/9781315558974. [ Links ]

[10] I. Kopric, & P. Kovac, Eds, European administrative space: Spreading standards, building capacities. Bratislava, Slovakie: NISPAcee Press, 2016. [ Links ]

[11] A. Larsson, E. Ranudd, E. Ronchi, A. Hunt & S. Gwynne, "The impact of crowd composition on egress performance," Fire Safety Journal, vol. 120, no. March 2020, 103040. doi: 10.1016/j.firesaf.2020.103040. [ Links ]

[12] J. Mair, & K. Weber, "Event and festival research: A review and research directions," International Journal of Event and Festival Management, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 209-216, 2019. doi: 10.1108/IJEFM-10-2019-080. [ Links ]

[13] J.F. Dickie, & W.M. Reid, "Discussion: Critical assessment of evidence related to the 1989 Hillsborough Stadium disaster, UK," Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Forensic Engineering, vol. 171, no. 4, pp. 179-180, 2018. doi: 10.1680/jfoen.18.00016. [ Links ]

[14] V. Filingeri, "Factors influencing experience in crowds - The participant perspective," Applied Ergonomics, vol. 59, pp. 431-441, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2016.09.009. [ Links ]

[15] L. Todd, A. Leask, & J. Ensor, "Understanding primary stakeholders' multiple roles in hallmark event tourism management," Tourism Management, vol. 59, pp. 494-509, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.010. [ Links ]

[16] M. Wagner, "The link of environmental and economic performance: Drivers and limitations of sustainability integration," Journal of Business Research, vol. 68, no. 6, pp. 1306-1317, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.11.051. [ Links ]

[17] M. Saunders, P. Lewis, & A. Thornhill, Research methods for business students, 7th ed. Harlow, England: Pearson Education, 2015. [ Links ]

[18] P.D. Leedy, & J.E. Ormrod, Practical research: Planning and design, 12th ed.Harlow, England: Pearson, 2021. [ Links ]

[19] J.W. Creswell, & J.D. Creswell, Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 5th ed. Los Angeles: Sage, 2020. [ Links ]

[20] The Republic of South Africa, "Safety at Sports and Recreational Events Act No. 2 of 2010," Government Gazette No. 33232, 27 May 2010. Available at: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a22010.pdf [Accessed 23 November 2021]. [ Links ]

[21] H. Zhang, 'Crowd-Induced Vibrations in Sports Stadia', May, 2019. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author: greg@misterjones.co.za

ORCID® identifiers

G.S. Jones: 0000-0002-4954-4725

S.Naidoo: 0000-0003-4284-516X