Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

On-line version ISSN 2224-7890

Print version ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.32 n.3 Pretoria Nov. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7166/32-3-2622

SPECIAL EDITION

Towards a relational framework of design

B. TladiI,*; K. MokgohloaII; A. BignottiI

IDepartment of Business Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa. B. Tladi: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0461-2840; A. Bignotti: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8213-279X

IIDepartment of Industrial Engineering, University of South Africa (Unisa), South Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3087-1582

ABSTRACT

The evolution of design has seen shifts towards more co-creation-based practice. This is not an entirely new development, as there has been a growing recognition and adoption of user-centred themes and terms such as co-design and human-centred design, among others. The ways of 'doing' such practices are becoming well-documented and presented through various tools and techniques; however, what kind of 'being' supports this? The paper reviews indigenous research methodologies (IRM) to propose the dimensions of a more relational framework of design. It reviews the 4Rs of indigenous research methodologies to propose five areas (expanded into eight dimensions) for a more relational framework of design. These dimensions can also support a way of 'being' that can guide the approach towards more co-creative thought and practice when 'doing' design. These dimensions can further support efforts to understand and to develop approaches that respond to the decolonisation and indigenisation of the design process.

OPSOMMING

Die evolusie van ontwerp toon skuiwe na meer sameskeppingspraktyke. Dit is nie opsigself 'n nuwe ontwikkeling nie, omdat daar 'n toenemende erkenning en aanneming van gebruikgesentreerde temas en terminologie soos 'co-design' en 'human-centred design' onstaan het. Die benadering tot sulke praktyke word al hoe beter gedokumenteer en aangebied via verskillende platforms en tegnieke. Hierdie artikel bestudeer inheemse navorsingsmetodologieë om die dimensies van 'n meer verhoudingsgerigte ontwerpsraamwerk voor te stel. Die vier R'e van inheemse navorsingsmetodologieë word gebruik om vyf areas (uitgebrei tot agt dimensies) van 'n meer verhoudingsgerigte ontwerpsraamwerk voor te stel. Hierdie dimensie ondersteun ook 'n benadering tot meer sameskeppende denkprosesse en praktyke wanneer daar ontwerp word. Hierdie dimensies dra by om die dekolonialisering en inheemsmaking van die ontwerpproses te verstaan en verder te ontwikkel.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Adding 'being' to the 'doing' of design

Participatory design is a "highly dynamic process, which includes linear co-design processes and consensus-building methodologies" [1] in which the role of the designer moves from being 'omnipotent' to being a co-participant in a facilitated collaborative effort. This approach implies the need for the recipients (i.e., the users, in design terminology) of the products of a design to be involved in the design process, and that their inputs be considered in the developmental activities [2].

This has an implication for the designer's orientation throughout the process. Design professionals ought to be aware not only of their own construction and interpretation of the social problems to be faced, but also of the contextual considerations of these issues. This therefore also requires that the use of design thinking - using design as a tool for thinking, rather than the approach of 'design thinking' - be considered with an "objective critical perspective" [3].

It is imperative that the involvement of users is not limited to mere consultation. The relevant stakeholders need to be engaged with in a manner that best facilitates active participation and integration of the various available competences [3].

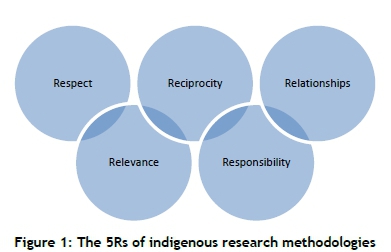

Such a shift in thinking about how we 'do' design is mirrored by earlier questions about research methodologies. Indigenous research methodologies (IRM) are interested in ensuring that research is not done on research participants, but rather with. (This mirrors other participatory-based research approaches, such as participatory action research and community-based participatory research.) These approaches require more than the mere inclusion of the participants' perspectives in the research process; they involve a deliberate attempt to research from the worldview of the participants [4]. The IRM literature has given much consideration to the position of the researcher, which relates to the 'being' of doing research. The 4Rs (which look at respect, relevance, reciprocity, and responsibility [5, 6, 7] - or the 5Rs, with the addition of relationships [8]) have been offered as a framework that guides how to relate and how to 'be' with those with whom the research activity is being conducted. This way of 'being' can also guide the approach of more co-creative thought and practice when 'doing' design.

This paper offers a preliminary response to the authors' musings in search of a framework of 'being' in design. It does not attempt to give an extensive validated model, but rather some antecedents worth considering following this initial prodding.

1.2 Aim and objectives of this preliminary inquiry

There has been a growing recognition and acknowledgement in the broader design world that the sustainability and appropriateness of design solutions need to be co-created with the users of such systems. The origins of such an approach are not new: the origins of participatory design go back more than 40 years. This has grown and evolved into a discipline of co-creative design approaches that see the user as a co-designer in the design process [9, 10]. There have been attempts to describe what this process (i.e. the 'doing' of design) looks like and its evolution (see [9], for example). However, what are the characteristics or features of such an approach? What are the different dimensions of the design process that would need to be reflective of such an approach?

There are parallels between what is posited by the decolonisation and indigenisation of evaluation practice, indigenous research methodologies, and co-creative design practice. All of these call for a more inclusive, participatory, dialogic - a more relational - way of engaging with different stakeholders. This is also particularly relevant for the beneficiaries of the created value. Much can be learnt from the indigenous research methodology paradigm in an attempt to answer these questions in design. Such an application can propose a more relational mode of doing design.

This introductory inquiry aims to offer a preliminary understanding of the following research question: What are the features (or dimensions) of a more relational approach to design?

The objectives of this paper are:

1) To review texts that focus on the 4Rs framework in an attempt to understand the factors involved in the IRM approach;

2) To analyse these texts to identify the characteristics that are informed by the involved factors;

3) To propose the dimensions that need to be organised in the move towards a more relational approach of design

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Co-creative design approaches

There are definitions of co-creation that describe it as an "active, creative and social collaboration process between producers and customers" [11]. Such collaborative practices offer significant opportunities for organisations, and the actors within their networks, to access new resources through the process of resource integration.

The evolution of design has seen a shift towards transformation design, which enables a wide range of stakeholders from differing disciplines to collaborate through the design process [9]. This requires a shift away from the 'expert mindset', which often tends to negate the creative potential of the involved individuals. Such dominant, 'top-down' structures are being dismantled by this more collaborative 'open access' approach to design. Mindset cultivation has a pertinent role in the process of value co-creation. It is also important that individuals claim their own creativity and behave in accordance with that belief [9].

Empathy is recognised as a crucial element in user-centric and innovation processes. This element urges not only a focus on the lived experience of users [12], but also encourages an attentiveness to all of the stakeholders who are involved in the process of innovation. It recommends that we listen to the "voices of difference" [13, 14, 15], and prompts us to ask ourselves how we may be able to listen to all of the stakeholders effectively to enhance the social value creation process. This supports the need for more collaborative approaches to address the often complex and systemic issues that allow practitioners to design with (rather than for) the respective stakeholders.

Co-design is often used as an umbrella term for participatory, co-creation, and open design processes [10]. Co-design reflects a fundamental change in the traditional designer-client relationship. The co-design approach enables a wide range of people to make a creative contribution to the formulation and solution of a problem. This approach goes beyond consultation by building and deepening equal collaboration between citizens affected by, or attempting to resolve, a particular challenge. A key tenet of co-design is that users, as 'experts' of their own experience, become central to the design process.

2.2 The 4Rs of indigenous research methodologies (IRM)

Just as in design, the research world has also seen a diversification of paradigms that aim to highlight the significance of contextualised local knowledge. It has been noted that the dominance of Western knowledge - particularly in the field of development - has resulted in the marginalisation and disqualification of non-Western knowledge systems [13]. This has led to an acknowledgement that more participatory voices are required, and that the indigenous knowledge of the involved parties (i.e., the tacit knowledge of the beneficiaries) is required to increase participation.

The inadequacies of knowledge (particularly in the development field fe) that is formulated in Western contexts have led to the recognition that alternate knowledge systems are required to address community issues appropriately [16]. The focus on a more pluralistic approach to knowledge systems - the development of a more "global body of ways of knowing" [16] - necessitates the creation of a process in which indigenous knowledge can be integrated into the development agenda, thus countering the "threats of the domination of knowledge commercialisation and commodification" [16].

IRM proposes guidelines for engaging community participants in the process of research and related activities. The definition of what constitutes 'indigenous' has expanded not only to refer to communities that belong to developing or underdeveloped areas, but also to include those that have been excluded or marginalised by processes that reflect more Eurocentic values, or those from the Global North [17].

The 4Rs of indigenous research methodologies

The 4 (or 5) Rs of IRM have been offered as a framework to describe the IRM research paradigm. The features of such a paradigm are [18, 19, 20, 4]:

• Ontology: Relationships with others based on the I/we relationship; "relationships are reality" [19]; realities are embodied, connected, layered.

• Epistemology: Constructed from relationships - forms mutual reality; "knowledge emanates from the experiences and culture of the people" [19]; legitimacy based on different systems of reality (based on the relational ontology).

• Axiology: Value system based on respect (ubuntu), cooperation; "ethics based on respect, reciprocity, shared responsibility between 'researcher' and 'researched'" [18]; knowledge comes from many varied sources.

Different texts have expounded on what these elements are, with different definitions being ascribed to each term. The 5Rs, as used in this study, are described as:

• Respect

• Relevance

• Reciprocity

• Responsibility

• Relationships

Some of the questions asked by a more indigenous research methodologies-based approach are these [19, 21]):

• (multiple realities) How does the research process accommodate and allow for the representation of multiple identities (and consequent realities)?

• (honouring existing relationships) How does the research support the inter-connectedness of the relationships involved in the research process?

• (languages and communication) How do we engage with the question of language? Which languages are predominant? How do these influence the research?

• (audience) Thisrelates to the audiences of the outcomes of research: who receives these outcomes (and how)? Who gets to engage with them?

• (plurality of different knowledge systems) How do we respond to the plurality of knowledge systems (i.e., different ways of knowing)?

These questions are also relevant to the context of design.

3 METHODOLOGY

The aim of this study was to determine whether the characteristics or features of relational design could be identified from texts in the IRM literature. The primary approach that was applied was a preliminary literature review to understand how IRM features could propose more relational modes of design. The methods of engaging with these texts were as follows:

(1) and (2): Following a review of the literature, convenience sampling of the available texts was performed to select texts that described the 4Rs in the context of indigenous research methodologies. Four main texts were selected, from which a definition of the 4Rs could be gleaned. These texts were:

Although there are other texts that refer to the 4Rs, these texts were selected because of their explicit definition of the 4Rs or 5Rs (as used in their respective studies), from which the theoretical propositions of IRM could initially be based.

(3): Although the same terms were used, the definitions differed, owing to the different contexts from which each paper was written. The definitions from each of the articles were noted, and then were thematically grouped. The different definitions were placed alongside each other to enable the analysis processes.

(4), (5), and (6): Each definition was then thematically analysed in two ways:

A. According to the generated codes, categories were identified and themes were generated from each definition (i.e., a number of themes were identified from each definition).

B. According to the generated codes, categories were identified and themes were generated based on each thematic grouping (i.e., a number of themes were identified from each definition grouping).

These codes were used to identify broader categories. The following analysis dimensions were applied to the codes and categories from the (B) analysis, the outcomes of which were used to develop the resultant themes:

i. (Basis of acknowledgement) Identifying the broader theme of each grouping (while asking the question: What does this thematic grouping acknowledge?).

ii. (Claims/values/assertions) Identifying the claims, values, or broad assertions of the theme identified from (i).

iii. The assertions from (ii) were then used to infer the analysis dimensions from each thematic grouping from the (B) analysis.

iv. The analysis dimensions from (iii) were then grouped according to broader categories that identified the areas of distinction offered by the IRM texts.

v. These broader category areas were then cross-referenced with the themes identified from the (A) analysis to help with developing a characterisation of each area.

No ethical clearance was required for this preliminary literature review.

Trustworthiness and limitations of the study

The study was limited to the above four primary texts. However, the number of texts used does not disqualify the exploratory nature of this study, as they serve as a first step to understanding more relational modes. These texts were selected and analysed to propose initial theoretical propositions that could be further built on in future work. The trustworthiness of the study can be described in these terms [23]:

• Dependability and confirmability: An audit trail was kept of all of the analysis steps. This was recorded in an Excel spreadsheet, the results of which were printed for further analysis. This was stored on the author's desktop and backed up on online platforms.

• Reflexivity: The author kept a mini-memo in which decisions and reflections during the analysis were noted. Each entry was dated, and all entries were stored in a single notebook.

4 RESULTS

Following the thematic analysis, there were five resultant main areas (A-E) that were found to highlight the IRM approach. These could be further described in eight dimensions, numbered 1 to 8.

A. Process and organisation: describes how the ways of engagement are organised (1).

B. Knowing: explores how we get to know in the process, according to the following dimensions:

i. Ways of knowing (2)

ii. Value (3)

iii. Information sharing (4)

C. Relationships: Considers the networks, and how we relate and what we share with one another in the process:

i. Relationships and networks (5)

ii. Acts of sharing (6)

D. Character: Our personal conduct in the process (7).

E. Benefits: A consideration of what the benefits are in the process, and who benefits (8).

These are presented in Table 2. The broad descriptions are framed as questions that the discussed dimensions aim to propose responses to (based on the text analysis)

5 DISCUSSION

The dimensions of the IRM definitions are used to propose a more relational framework of practising design. This is a practice that recognises co-design, and that also highlights the quality of being in the process. Each of the identified dimensions is described below (with the applicable Rs from the IRM literature noted in italics).

5.1 Organisation

Overview: There are particular ways in which more relational methods of engagement are organised.

Design processes that are rooted in a more relational mode have a more equal dynamic between those who are involved in the design process. This aspect of equality spans the range of the design process, in which the rights of all who are involved are discussed, and consensus is reached before any project can start. This discussion between participants continues throughout the process, and even results in post-engagement following the completion of the project [5]. The rights and regulation aspects of the process document the protocols and risks, and ensure that these are agreed on. The terms of ownership (in respect of the process and the related outcomes) are clearly defined. It is also clearly communicated what permission is granted in respect of the information that is shared. Although this adds to common ethical clearance practice, it is important to note - because it is not taken for granted that everything that is shared in the process is fit and fair for public consumption (i.e., by those who were not part of the process). The structure of the team involved is flat ("redistribution is the sharing obligation" [5]), in contrast to hierarchical, bureaucratic structures [8]. It is integrative and holistic in its representation of the affected parties of interest.

Questions - points to consider:

• How do we ensure that the environments in which such activity takes place are also organised in a way that supports the processes and effectiveness of the endeavour?

• How do we engage the structures of such environments (are they always visible?)? How do we engage with invisible contextual structures?

5.2 Value

Overview: Different aspects are highly considered in the relational framework context, and there is a pronounced recognition of what counts. Valued items are not limited to those aspects that can be tangibly seen; they also include qualitative (intangible) elements.

A more relational approach recognises the resourcefulness of all who are involved; it acknowledges all who participate in the co-design endeavour. The types of resources that are acknowledged are seen as both intangible and tangible assets of the process [5]. Following on from the equality of all participants, all decisions are reached by consensus. This also shows that all contributions from those who participate are valued. All decisions are taken according to their relevance to the community, and should be relatable [22]. The contributions and knowledge from daily life are taken in tandem with what would be termed 'expert knowledge' [5, 6]. Data from lived experiences is noteworthy. The process and outcomes have value and worth to others outside the process as well.

Questions - points to consider:

• How (exactly) are equal contributions facilitated - is it democracy? Or do other (consensus-based) processes facilitate this - what are they?

• How do we actually document and capture the 'lived experience' without objectifying co-designers in the process?

5.3 Ways of knowing

Overview: Considering that a more relational way is inclusive of all the participants in the system, it also recognises that the participants contribute meaningfully to the process by sharing of themselves, their historiesand the sum total of their relationships. The areas of knowledge vary, and can be sourced from different parts of the system, all of which have legitimacy.

A relational framework recognises that there are different ways of knowing: there is a consideration of the multiplicity of knowledge systems, and the process accommodates such diversity [8, 22]. Because these are often rooted and reflected in different cultural and traditional contexts, there is sensitivity about ensuring that these ways of being are neither infringed nor impinged upon. Instead, there is an honouring and a celebration of the community's culture and heritage [22], and an openness to different worldviews. Such an expansive consideration of different knowledge systems also translates into a readiness to acknowledge different value systems.

Questions - points to consider:

• In such an expansive consideration of different ways of knowing, are there any sources of knowledge that are considered illegitimate, or that are discredited? What informs this?

• How do we address a 'clash' or possible conflict of worldviews? How are these reconciled?

• How do we develop sensitivity to those things that are unseen, such as values?

• How do we surface this multiplicity of ways of knowing?

• How do we engage with the unseen contexts of assumptions and paradigms? (How are these also surfaced for collective engagement?)

5.4 Information sharing

Overview: Because a relational framework recognises the interconnectivity of things and the dependence on the whole, the contributions of different parts of the whole are seen as relevant to the whole. Data is not limited to coming from one source (e.g., experts): it is accepted and understood that data can be presented by and is given from multiple sources. This is also supported by the quality and value of inclusivity, in which all types of form and life form (animate and inanimate) are related to the whole and therefore can contribute as data. This also supports the aspect that the exchange among all parts of the system is reciprocal and that all things in the system have a responsibility. Therefore, all parts are not static members, but contribute something to the whole.

Data, or what counts as valuable information, is reflected and recognised by the different knowledge systems under consideration (relevance). This is reflected in the use of cultural metaphors, idioms, and other embedded knowledge artefacts; culture has legitimacy in a relational mode of design. Thus there is an inclusive approach to what counts as data (relationship is the kinship obligation) [5]. Processes are available to facilitate the communication of these and to make the knowledge or information accessible [6]. Data from the lived experience is considered and engaged with sensitively (respect). Such a diverse view of knowledge reflects that knowledge and data are not monolithic: the polylithic expression of reality exists all around and in all ways.

Questions - points to consider:

• Given that there are multiple ways of knowing, how do we consider terms such as 'objectivity' or 'subjectivity' in the process?

• How do we reconcile different ways of knowing in the process? (Do these need reconciliation?)

• How are 'decisions by consensus' reached when data is evaluated differently?

5.5 Networks and relationships

Overview: The interdependency and connections between others need to be recognised, maintained, and facilitated. Each participant recognises the role that they play in the greater whole (the broader system), and understands their connections with others. A nuanced understanding of the dynamics that result from the connections is understood. These dynamics work together in a harmonious way.

The basis of the relational framework is the awareness and acknowledgement of the relationships and networks ("responsibility is the community obligation" [5]) that are ingrained in the co-design process. Such a view thus recognises and validates the roles and positions of each person who is involved. Each individual has a role to play in the community. Because each person's position is not seen in isolation, this highlights the reciprocal nature of all engagements, with each person thus having a joint responsibility and accountability (relational accountability) to others. This responsibility extends to acts that help to nurture and maintain the existing relationships in the network [6]. There is a recognition and acceptance that an interdependability exists between all participants in the process (interconnected parts of the system). This networked view of relationships is reflective of a systemic view that needs to be upheld in co-design activities.

Questions - points to ponder:

• How is conflict addressed? How do we deal with disharmony within the system?

• How are these relationships 'formed' - or formally engaged?

• How are these relationships sustained? Do they change over time? If so, what would cause this?

• What other personal qualities support and uphold such a networked view of co-design processes?

5.6 Acts of sharing

Overview: This reflects the flows of exchange that are present in the community of co-designers. There is a dynamic interaction among those involved in the process and in the channels involved to facilitate the interactions. The exchange is not one-way; it is a mutual interaction in which the different aspects of value are shared between the participants in the process. The artefacts of exchange are maintained within the [eco]system.

This relates to the R of reciprocity, which sees "redistribution as the sharing obligation" [5]. This dimension recognises that all who are involved in the design process are engaged in some kind of relationship, and that there is a responsibility not only to receive in the process, but also to contribute (give). This dimension again supports the view of the resourcefulness of everyone involved in the process, and regards such contributions as gifts to the overall value-creation endeavour [5]. There is a cyclical view of the contributions made in the process ("reciprocity is the cyclical obligation" [5]), which recognises the systemic ripple effect of an action on all who are involved. Fair, considerable, and possibly equal value is given to different types of contribution [5, 6, 22]. This supports the 'value' dimension, that everyone has something of value to offer.

Questions - points to ponder:

• What networks exist to facilitate such exchanges?

• In actual terms, what gets exchanged in the process?

• Are all contributions valued equally? How do we evaluate these?

5.7 Character of being

Overview: Character cannot be excluded from such an approach. The ways of 'doing' are enacted, and they emanate from the qualities that we possess and then choose to display in the process. As participants in the process (and because we are all equal), we conduct ourselves in particular ways that allow everyone to participate equally, and that support the others modes of relationality.

The ethos of such an approach to design is woven and held together by an ethic of care ("responsibility is the community obligation"[5]). Such qualities support a way of being that emphasises the softer (and perhaps slower) qualities of listening and being sensitive to others. This is contrasted with qualities that coerce and are dismissive in the interests of the speed (at the expense of the impact) of the process. There is a sensitivity of engagement (respectful representation) as well as sensitivity to what information can be transmitted from both those within and those external to the design process. There is an acceptance that what is shared (communicated) is confidential and sensitive, and there is adherence to the agreed upon protocols to govern this transmission. There is an inclusive disposition ("relationship is the kinship obligation"[5]) that feels no prejudice towards and makes no judgement of others. It accommodates the equality of all. There is a recognition of personal responsibility, and a responsibility towards others (responsibility). Everyone is equal and has an equal stake. All participants have equal responsibilities to uphold; they are responsible to the whole, and are accountable to all [6].

Questions - points to ponder:

• Who is considered as external to the process? What are the boundaries of inclusion/ exclusion?

• Are there specific roles that support this process? Do different roles emphasise particular characteristics or qualities?

• Who is in charge of managing and ensuring adherence to the agreed upon protocols of the engagement?

5.8 Benefits and outcomes

Overview: Because everyone has an equal stake, this applies throughout the whole process, including the benefits (and even the 'losses') in every stage of the process.

The aims of the process are mutually decided on, and the outcomes are mutually beneficial (reciprocity and reciprocal appropriation) [6]. The goals of the process are the goals of the community that is involved (mutually-shared goals). The benefits of the process translate into benefits for the system (macro-view) concerned, and they are relevant to the community concerned [6, 22]. The benefits and outcomes serve the whole (and not a select part); or, at the very least, they do not compromise the health of the whole (systems view). The ramifications and consequences of the process are not limited only to the system in question. Because of the interconnectedness of all things, the inputs and outputs of the process consider both micro- and macro-systems [8]. The benefits accrue throughout the process (all stages of the process - beginning, middle, end) [8].

Questions - points to consider:

• Does this have implications for 'character'? How do we carry ourselves in a way that benefits the process as well? What would such qualities be?

• Since the idea of benefit is shaped by our inner values, how do individuals with different values align themselves with a common goal?

• How do we respond to losses in the process? (Is there always value in a more relational mode of co-design?)

• Are there different benefits or outcomes that are relevant to particular stages of the process?

6 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This preliminary review of the 4Rs' definitions from the IRM literature identified five broad areas that describe such approaches. These areas can be further expressed as eight dimensions. These dimensions can also support a way of 'being' that can guide the approach towards more co-creative thought and practice when 'doing' design. This can result in the positive sustainability and appropriateness of co-created design solutions. The implications of these initial musings can offer benefits such as these:

• (Process and organisation) Understanding and engaging the resourcefulness of all participants in the process

• (Knowing) An awareness of both tangible and intangible assets in the process

• (Knowing) Engaging the lived experiences of all participants, and recognising these as valid data to inform the outcome

• (Knowing) Integration of different world views

• (Relationships) Understanding the role of each participant and acknowledging the interdependability of all the role-players

• (Character) Upholding an ethic of care, and handling all data and information in the process with sensitivity

• (Benefits) Mutually beneficial goals that serve both micro- and macro-levels of the system (participating community)

This study is also an example of trans-disciplinary application, through the transfer of relational dimensions in research to identify the features that can advance the 'being' of co-creative design. Future work could extend the identified theoretical propositions to other sources in the IRM literature to strengthen the basis of the developed dimensions of relational design. These dimensions could further support efforts to understand and to develop approaches that respond to the decolonisation and indigenisation of the design process.

There were a number of other points that need to be considered in each of these areas and dimensions. These are potential areas for future theoretical understandings of such an approach.

Recommendations

• As this was a preliminary attempt to understand relationality in the design context, this initial understanding could be expanded and extended to the appropriate IRM literature.

o This would enhance the trustworthiness of the study in the following ways: credibility, through prolonged engagement with other texts in the field; and positively advancing the transferability of the study.

• These proposed areas of 'being' could be applied to an active design project in order to test the proposed dimensions practically, and to document the lessons to be learnt from such an application.

This practical application could also help to respond to the questions and considerations that were noted in the discussion section, and could serve to qualify the proposed dimensions further.

REFERENCES

[1] E. Manzini, "Making things happen: Social innovation and design," Design Issues, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 57-66, 2014. [ Links ]

[2] E. Bjogvinsson, P. Ehn and P.-A. Hillgren, "Design things and design thinking: Contemporary participatory design challenges," Massachusetts Institute of Technology Design Issues, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 101-116, 2012. [ Links ]

[3] A. Chick, "Design for social innovation: Emerging principles and approaches," Iridescent, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 78-90, 2012. [ Links ]

[4] S. Wilson, "What is an indigenous research methodology?" Canadian Journal of Native Education, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 175-179, 2001. [ Links ]

[5] L. D. Harris and J. Wasilewski, "Indigeneity, an alternative worldview: Four R's (relationship, responsibility, reciprocity, redistribution) vs. two P's (power and profit). Sharing the journey towards conscious evolution," Systems Research and Behavioural Science, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 1-15, 2004. [ Links ]

[6] R. P. Louis, "Can you hear us now? Voices from the margin: Using indigenous methodologies in geographic research," Geographical Research, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 130-139, 2007. [ Links ]

[7] B. Chilisa, Indigenous research methodologies, Los Angeles SAGE Publications, 2012. [ Links ]

[8] D. Tessaro, J.-P. Restoule, P. Gaviria, J. Flessa, C. Lindeman and C. Scully-Stewart, "The five R's for indigenizing online learning: A case study of the First Nations Schools' Principals Course," Canadian Journal of Native Education, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 125-143, 2018. [ Links ]

[9] E. B. Sanders and J. Stappers, "Co-creation and the new landscapes of design," Co-Design, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 5-18, 2008. [ Links ]

[10] N. Matias, "Co-design in a historical context," 2011. [Online]. Available: https://civic.mit.edu/index.html%3Fp=407.html#:~:text=Cooperative%20design%20methods%20originated%20in,process%20of%20technologies%20at%20work.&text=To%20do%20this%2C%20they%20developed,envision%20and%20articulate%20their%20requirements [Accessed 23 May 2021]. [ Links ]

[11] F. T. Piller, C. Ihl and A. Vossen, "A typology of customer co-creation in the innnovation process," 29 December 2010. [Online]. Available: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1732127 [Accessed October 2019]. [ Links ]

[12] J. Thomas and D. McDonagh, "Empathic design: Research strategies," Australasian Medical Journal, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1-6, 2013. [ Links ]

[13] J. Briggs, "The use of indigenous knowledge in development: Problems and challenges," Progress in Development Studies, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 99-114, 2005. [ Links ]

[14] M. Sengupta, "Obstacles to the use of indigenous knowledge," Development in Practice, vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 880894, 2015. [ Links ]

[15] G. Wangu, D. Nyariki and M. Sakwa, "The role of indigenous knowledge in socio-economic development," International Journal of Science and Research, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 32-37, 2015. [ Links ]

[16] J. A. Owuor, "Integrating African indigenous knowledge in Kenya's formal education system: The potential for sustainable development," Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 21-37, 2007. [ Links ]

[17] K. C. Snow, D. G. Hays, G. Caliwagan, J. F. J. David, D. Mariotti, J. M. Mwendwa and W. E. Scott, "Guiding principles for indigenous research practice," Action Research, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 357-375, 2016. [ Links ]

[18] B. Chilisa, A postcolonial indigenous research paradigm, Cape Town, Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), 2011. [ Links ]

[19] B. Chilisa, "Key note: Equality in diversity: Indigenous research methodologies," American Indigenous Research Association Conference, Montana, October 2015. [ Links ]

[20] P. Walker, "Indigenous paradigm research," in Methodologies in peace psychology, D. Bretherton and S. Law, Eds., Switzerland, Springer International Publishing, 2015, pp. 159-175. [ Links ]

[21] B. Chilisa, T. E. Major, M. Gaotlhobogwe and H. Mokgolodi, "Decolonizing and indigenizing evaluation practice in Africa: Toward African relational evaluation approaches," Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 313-328, 2016. [ Links ]

[22] V. J. Kirkness and R. Barnhardt, "First Nations and higher education: The four R's - Respect, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility," in Knowledge across cultures: A contribution to dialogue among civilisations, R. Hayoe and J. Pan, Eds., Hong Kong, Comparative Education Research Centre, 2001, pp. 1-21. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author: bontletld@yahoo.com