Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

On-line version ISSN 2224-7890

Print version ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.29 n.3 Pretoria Nov. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7166/29-3-2058

SPECIAL EDITION

The megaproject sponsor as leader

W. LouwI, *, #; J. WiumII; H. SteynIII; W. GeversI

IUniversity of Stellenbosch Business School, South Africa

IIDepartment of Civil Engineering, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

IIIDepartment of Engineering and Technology Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The importance of the sponsor role, including its contribution to the success or failure of a project, is widely recognised in the project management literature. References to the sponsor's leadership, and the substantial component it represents in the profile of the sponsor, are equally prevalent in the literature reviewed. A megaproject is a large-scale, complex venture that typically costs US$1 billion or more, takes many years to develop and build, involves multiple public and private stakeholders, is transformational, and influences millions of people. Executive sponsors are primarily allocated to projects of strategic importance that are complex, carry a considerable degree of risk, and are very visible. A megaproject is thus entitled to a sponsor from the executive (most senior) ranks within an organisation. Rather than joining the debates on complexity and leadership in the project management literature, this paper explains how leadership theories are used to identify instruments that can assist in the assessment of the leadership style and traits/attributes of a sponsor. A framework is then proposed to identify assessment instruments to evaluate the leadership style and leader traits/attributes of a project sponsor.

OPSOMMING

Die belangrikheid van die rol van die bestuursborg, insluitend die bydrae wat hy/sy maak tot die sukses of faling van ' n projek word wyd erken in die projekbestuur literatuur. Verwysings na die leierskapsrol van die bestuursborg asook die wesenlike komponent wat dit uitmaak van die profiel van die bestuursborg word bykans net soveel aangetref in die literatuur. ' n Megaprojek word gedefinieer as 'n grootskaalse, komplekse onderneming wat tipies 1 miljard Amerikaanse dollar of meer kos, etlike jare neem om te ontwikkel en te bou, veelvuldige publieke en privaat belanghebbendes betrek, transformasioneel van aard is, en miljoene mense beïnvloed. Uitvoerende bestuursborge word hoofsaaklik aangewys vir projekte van strategiese aard wat kompleks is, ' n beduidende hoeveelheid risiko dra, en uitsonderlik sigbaar is. Dit is dus duidelik dat ' n megaprojek geregtig is op ' n bestuursborg vanuit die uitvoerende en mees senior bestuursvlakke van ' n organisasie. Eerder as om aan te sluit by die debatte oor kompleksiteit en leierskap in die projekbestuur literatuur, dui hierdie artikel aan tot welke mate leierskapsteorieë benut kan word om instrumente te identifiseer wat kan meehelp in die evaluering van leierskapstyle asook die leierskap eienskappe/ attribute van ' n bestuursborg. Ter afsluiting word ' n raamwerk voorgestel om assesseringsinstrumente te identifiseer vir die evaluering van leierskapstyle en leier eienskappe/ attribute.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the project management literature where the role of the sponsor is addressed, it is widely recognised that that role is a very important component of any project, and that the sponsor makes a significant contribution to the success (or failure) of the project. Equally prevalent in the literature reviewed are references to leadership in the profile of the sponsor - for example, by Turner and Müller [1], Crawford et al. [2], West [3], Remington [4], Bourne [5], Van Heerden et al. [6], Barshop [7], and PMI [8]. Leadership is also distinctly visible in the role of the sponsor as described in the international standards reviewed (Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), 6th edition [9]; IPMA Competence Baseline (ICB) Version 4 [10]; APM Body of Knowledge, 6th edition [11]; The Office of the Government Commerce (OGC), United Kingdom standards [12]. All of these references confirm the substantial component of leadership in the profile of the sponsor.

Against this background, this paper shows how leadership theories are used to identify instruments that can assist in the assessment of the leadership style and leadership traits/attributes of a sponsor. To end, a framework is proposed to identify assessment instruments to evaluate the leadership style and leader traits/attributes of a project sponsor.

For the purpose of the paper, the term project includes the descriptors project based programme and megaproject. Similarly, the term project manager includes the descriptors project director, programme manager, and programme director.

Following Flyvbjerg [13], a megaproject is defined as a large-scale, complex venture that typically costs US$1 billion or more, takes many years to develop and build, involves multiple public and private stakeholders, is transformational, and impacts millions of people.

The Project Management Institute (PMI) [14] states that executive sponsors are primarily allocated to projects of strategic importance that are complex, carry a certain degree of risk, are highly visible, and are allocated a very sizeable budget. It can accordingly be deduced that a megaproject sponsor is from the executive (most senior) ranks within an organisation. For the remainder of this paper, where the megaproject sponsor connotation is used, it implies by default that the sponsor is an executive sponsor.

The element of the complexity of projects deserves some attention in the context of the executive sponsor and his/her leadership. Stacey [15] states that complex projects require extraordinary leadership capabilities and management skills. Remington [4] also argues that there is a positive correlation between project success and the capacity of the executive sponsor to recognise complexity as soon as possible.

The literature often distinguishes between a 'complex' project and a 'complicated' project. The perspective of Chapman [16], Whitty and Maylor [17], and Maylor et al. [18] is that the distinction between the two is found in the nature of the relationships between the elements of the project system. Their view is that large-scale engineering and construction projects need not necessarily be viewed as complex projects; but they are complicated projects. For this view to be valid, the interactions with and the influence of the environment need to be predictable, and may sometimes be trivial.

Remington [4] argues that leadership roles in large complex projects in the public sector are not as well-defined as those for similar projects in the private sector. Her position is that selecting a single sponsor in a private sector organisation with high leverage who can take responsibility for the success of the project is attainable. However, it is less attainable in the public sector, due to a multi-layered executive leadership structure.

This paper does not elaborate on the theories of leadership and complexity of projects. Instead, it provides insight into the sponsor / leadership relationship by referring to leadership vs management in the role of the sponsor. An overview of the current literature on the relationship between the sponsor and project manager, and leadership effectiveness in the role of the sponsor, concludes section 2 of the paper. In the sections that follow (3, 4, and 5), leadership styles, emotional intelligence in the leadership context, and the identification of leadership attributes are presented as they pertain to the sponsor. Finally, the paper presents a guideline for the application of instruments for the measurement of leadership attributes.

2 SPONSOR / SPONSORSHIP AND LEADERSHIP

Crawford et al. [2] reviewed a number of national and organisational standards for project management in order to define the terminology sponsor/ sponsorship in the project context. Six key themes identified by the authors emerge from the review:

• The sponsor role is at a senior level in the owner (often also referred to as the 'client' or 'customer') organisation;

• The sponsor role contains substantial dimensions of leadership (as opposed to being just a management role);

• The sponsor is responsible for ensuring that an effective governance framework is created for the project;

• The sponsor is the owner of the business case for the project, and is ultimately responsible for the delivery / realisation of the benefits projected within the business case;

• The sponsor is positioned structurally on the interface between the owner and project organisations, such that decision-making and support to the project manager are enabled, particularly for issues beyond the control of the project manager; and

• An inconsistency exists between the standards in how the role of sponsor is carried out (either by an individual or a group).

The positioning of the sponsor is in a specific organisational context - i.e.. between the business (permanent organisation) and the project (temporary organisation). It is primarily the upward relationship between the sponsor and the board / senior executive, and the downward relationship between the sponsor and the project manager(s), that forms the basis for the identification of leadership requirements in the role of the sponsor.

2.1 Key concepts in sponsor leadership/management

2.1.1 Confused state of the leadership field

Yukl [19] states that the 'confused state' of the leadership field can in part be attributed to (i) the very large volume of publications, (ii) the great difference in approaches, (iii) the large number of confusing terms, (iv) the restricted focus of most researchers, (v) the high percentage of irrelevant or unimportant studies, and (vi) the absence of an integrating conceptual framework.

A quarter of a century later, it is apparent that leadership continues to be a field for much debate and disagreement, in which most researchers prefer multiple definitions of leadership and lists of attributes, as seen in Morris [20] and De Klerk [21]. Available statistics, particularly on the topic of leaders / leadership in the literature from Amazon.com, indicate that it is a large and important subject [3],[21],[5]. It is accordingly concluded that the leadership field needs to be approached with caution.

2.1.2 Leadership and/or management

As previously mentioned, the literature confirms that the sponsor role is in essence a leadership role. However, the sponsor is also required to give direction and to clarify the framework for effective governance, of both the organisation (corporate) and the project. This brings a management dimension to the role. De Klerk [21] points out that decision-making (including strategic thinking and long-term planning) is similarly regarded as a managerial activity within leadership.

The examples provided allow the authors to conclude that there is a need and a place for both governance and decision-making in the role of the sponsor, and that it is unwise and incorrect to separate leadership and management in the role too forcefully. The reflections by West [3], Morris [20], De Klerk [21], and Bourne [5] on the matter of leadership and/or management support this conclusion.

2.2 The relationship between the sponsor and the project manager

In the organisational context, the sponsor is positioned at the interface between executive management/the board (permanent organisation), and the project team (temporary organisation). This implies that the sponsor is at a higher-order leadership/management level in the organisation than the project manager [3],[4],[5],[6].

The relationship between the sponsor and the project manager is critical. A well-informed and insightful sponsor will realise that he/she is the senior partner in a relationship based on collaboration. Accordingly, the sponsor will not trespass on the typical responsibilities of the project manager in executing the project [3],[20],[5],[7].

Turner and Müller [1] state that the best project performance is achieved where there is close collaboration between the client (i.e., the sponsor as representative of the client) and the project manager. Turner and Müller add that such close collaboration between the sponsor and the project manager, supported by appropriate communication, has been identified as a prerequisite condition for project success.

In related comments, Turner and Müller [1] and Turner [22] state that there is a negative (potentially contentious) correlation between the visionary leadership competence of the project manager and project success. Their perspective is that the project manager is required to remain focused on the delivery of the project as approved. If the project manager is too visionary inclined, he/she will compromise the time and cost objectives of the project - i.e., there will be a negative impact on project success. Visionary competence and ensuring that the project remains linked to the strategy of the (parent) organisation, need to remain with the sponsor role.

The 'project team' conceptually includes the sponsor, and requires a very clear role clarification between the sponsor and those who report to him/her, such as the project manager(s). Given the critical nature of the relationship, it is important that the sponsor appropriately uses the array of psychometric and other assessment instruments available prior to the appointment of the project manager. This statement is equally valid: that it is just as important that the board/senior executive use the assessment instruments appropriately prior to the appointment of the sponsor.

The authors found that it is a challenge to derive from the literature a description of the leadership role of the sponsor. This is because the literature typically focuses either on leadership in the general management domain, or on leadership in the project management/project manager domain. The role of the sponsor as leader in a collaborative relationship with the project manager is addressed to a limited extent in the literature. Similarly, it seems as if very little has been written about decision-maker(s) applying their mind(s) before the appointment of the sponsor to the project.

Bourne [5] makes a relevant comment on the governance process of nominating / appointing the sponsor. She states that, although the era of the 'accidental project manager' has largely passed, the age of the 'accidental sponsor' persists. Therefore, this paper incorporates a wide but concisely described array of leadership styles, traits, and attributes when addressing the role of the sponsor as leader. This aims to assist in the governance process of nominating and appointing the sponsor.

2.3 Leadership effectiveness of the sponsor

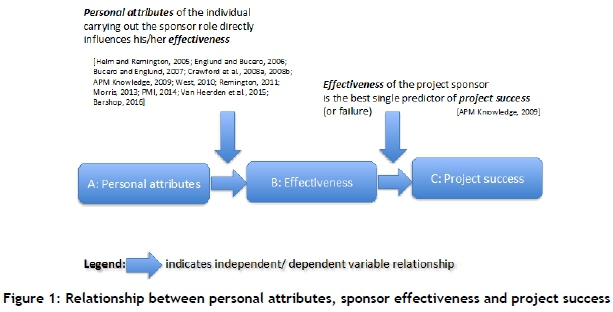

Leadership effectiveness can manifest itself in multiple ways. It ultimately depends on how well the leader chooses on a daily basis between a diverse set of behaviours. De Klerk [21] states that these behaviours can oscillate from setting direction that inspires, through providing emotional support with compassion, to ensuring that the required governance is in place and is adequately monitored. Integral to effective leadership are the concepts of leadership styles, interpersonal skills (specifically emotional intelligence), and traits and attributes. In the remainder of the paper, the identification of leadership styles, leadership traits, and interpersonal skills will be expanded upon in the relationship between attributes, effectiveness, and project success (Figure 1).

De Klerk [21] states that there is no one best way to be a leader, and that there is no single set of attributes that will guarantee project success, because the personalities of leaders and their followers and the contexts of projects vary.

3 LEADERSHIP STYLES

3.1 Leadership styles selected for evaluation

For the purpose of this paper, the leadership styles identified below are evaluated (with reasons provided). As criteria for inclusion in the selection, particular emphasis is placed on the availability of a style assessment instrument, on project management relevance, and on being part of latest developments ('current-ness'). It is also to be noted that each style is mostly underpinned by a specific theory. The selected leadership styles are as follows:

• Transformational leadership: a distinct component of the Multi-factor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) assessment instrument;

• Transactional leadership: a distinct component of the MLQ leadership assessment instrument;

• Situational leadership: referenced in the project management context;

• Authentic leadership: more contemporary / modern literature discussion, and measured with the Authentic Leadership Questionnaire (ALQ);

• Servant leadership: more contemporary / modern literature discussion, and possible to measure;

• Charismatic leadership: accelerated development of theory in recent times, and a distinct component of the Leadership Behaviour Inventory (LBI) leadership assessment instrument in the South African context;

• Visionary leadership: accelerated development of theory in recent times, and a distinct interface with emotional intelligence;

• Complexity leadership: potentially answering the questions of complex vs complicated, and the possibility for use in the context of a megaproject; and

• Shared leadership: addressing the phenomenon that organisations are migrating / have migrated to a knowledge-driven era in which multi-cultures and multi-geographies are distinctly prevalent.

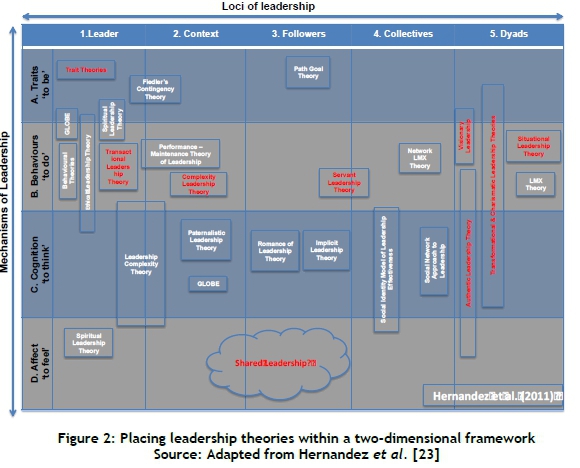

To provide an indication of the leadership theory and style coverage in the paper, the following context is provided: Hernandez et al. [23] developed a two-dimensional framework that reflects (i) where leadership comes from (the locus) and (ii) how leadership is transmitted / enacted (the mechanism).

The framework in Figure 2 depicts the placing of an array of leadership theories that have been developed since the early 1900s within such a two-dimensional framework (loci and mechanisms). The theories underpinning the leadership styles selected by the authors for evaluation are presented in bold red in Figure 2.

Some of the leadership styles (and their respective theories) selected for evaluation are not reflected in the original framework of Hernandez et al. [23] - i.e., servant, visionary, and shared leadership. Servant leadership theory and visionary leadership theory are placed in the framework to demonstrate their connectedness to the transformational, charismatic, and authentic leadership theories. Hernandez et al. [23] also posit that shared leadership theory is accommodated in the framework by considering the full spectrum of loci and mechanisms.

The leadership styles (underpinned by their respective theories) selected for evaluation indicate a distinct presence in the 'behaviours (to do)' mechanism, spread out over the whole spectrum of leadership loci. This is not unexpected, and it fits well with the central role that 'behaviours' play in the leadership role of the sponsor. Sparrowe and Liden [24] infer specifically that behaviours are the primary mechanism for leadership. The authors thus conclude that leadership is a distinct 'behaviour' mechanism within sponsorship.

3.2 Evaluation of selected leadership styles

West [3] comments that the first key skill the sponsor requires for the leadership component of the role is vision. This comment is not only directed at identifying whether the sponsor has the ability to be visionary. It also focuses on the issue that the development of vision for the project needs to be both compelling and powerful in order to align those involved with the project.

The transformational, charismatic, and visionary leadership styles are part of what is termed 'new-genre' leadership theories. They definitively incorporate and emphasise concepts such as symbolic leader behaviour; being visionary; communicating inspirational messages; surfacing emotional feelings; propagating ideological and moral values; and being intellectually stimulating. Visionary leadership is pertinently influenced by the act of vision creation. However, it is not a leadership style that is accompanied by an operationalised and validated measurement instrument. Transformational and charismatic leadership continue to be mentioned in the literature in the same context, despite the concerns raised by Yukl [25] and Antonakis et al. [26]. Yukl states that charismatic and transformational leadership are regularly considered to be the same. Yet there are credible differences that cannot be ignored or disregarded, and crucial conceptual deficiencies that need to be addressed. Antonakis et al. [26] supports the argument of Yukl [25] by stating that charismatic and transformational leadership are related, but that they are theoretically recognisably different. Judge et al. [27] maintain that, in the majority of cases (in the context of transformational and charismatic leadership styles), an individual with a high score on one leadership style will also have a high score on the other leadership style.

From the literature analysis on leadership, it is possible to contextualise the role of the executive sponsor in an 'identification of leadership' construct, as follows:

• Leadership within the sponsor profile is a given;

• Assistance to the decision-maker(s) responsible for the appointment/selection of the sponsor is available. The leadership style of the incumbent can be determined via an operationalised and validated assessment instrument;

• There is no leadership style that on its own contains all the elements required for effective leadership;

• Outstanding leadership relies significantly on the action of putting into words and feelings a viable and inspiring vision; and

• Identifying whether the sponsor has the ability to be visionary can be performed via the MLQ and LBI assessment instruments. Very importantly, this can ensure that the project remains linked to the strategy of the parent organisation.

By using the construct above as a filter for screening the nine leadership styles selected, four styles remain for further consideration. Bass and Avolio [28] argue that this number arises because transformational and transactional leadership are merged into one style derived from the full-range transformational leadership (FRTL) theory. This merging creates the broader context of the transformational leadership style. Additionally, those theories that are not supported by an operationalised and validated measurement instrument are eliminated from the list. The four theories remaining are transformational, charismatic, servant, and authentic leadership.

Authentic and servant leadership are different from transformational (and charismatic) leadership. Diddams and Chang [29] conclude that creating an inspirational vision to motivate followers is not necessarily the forte of an authentic or servant leader. The intent of reducing the number of theories is not to reduce them to an absolute minimum. Rather, it is to identify leadership styles that enable the decision-maker(s) to assess practically the leadership style of the designated sponsor on a megaproject prior to appointment.

The authors thus conclude that transformational and charismatic leadership styles are the preferred styles to be tested for when identifying an executive sponsor for a megaproject. Operationalised and validated measurement instruments support both leadership styles. For transformational leadership it is the Multi-factor Leadership Questionnaire, based on the work of Bass and Avolio [30], and referred to as the MLQ Form 5X. For charismatic leadership, it is the Leadership Behaviour Inventory, based on the work of Spangenberg and Theron [31] and referred to as the LBI.

At this juncture it is important to note that there is a relationship between the emotional competencies of the leader (including, among others, emotional expressivity) and a range of leadership theories. Groves [32] states that evidence for the existence of the relationship is provided by theoretical and empirical studies on transformational, charismatic, and visionary leadership.

3.3 Conclusion on leadership styles

No leadership style on its own contains all the elements required for effective leadership. Yukl [33] states that it is also not reasonable to expect that all aspects of leadership behaviour should be included in one theory. Dulewicz and Higgs [34] suggest that a consensus is developing in the leadership literature that there is no one leadership style for effective (leadership) performance. De Klerk [21] states that, although there are multiple instances of demonstrated good leadership, there is no one particular optimal leadership style that can be advanced for project management. The authors are of the opinion that the same argument can be offered for executive sponsorship.

Since the beginning of this millennium, a growth in emerging leadership theories (e.g., neurological perspectives on leadership) has occurred. There has also been a continued increase in theories relating to leading for creativity and innovation, toxic/dark leadership, and strategic leadership [35]. However, a number of established leadership theories (and their styles) continue to be of interest in the leadership field. These theories and styles include neo-charismatic (which provides for transformational and charismatic leadership), information processing, trait, and leader-follower exchange leadership. Other leadership theories, such as behavioural approaches, contingency theory, and path-goal theory have not attracted similar interest [35].

4 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (EI) WITHIN THE LEADERSHIP CONTEXT

As indicated in the 'identification of leadership' construct above, a number of leadership styles acknowledge that outstanding leadership relies significantly on the action of putting into words and feelings a viable and inspiring vision. Part of 'putting into words and feelings' includes the concept of emotional expressivity. Groves [32] posits that emotional expressivity is described as a communication style that contains distinct elements of variation in voice, facial expressions, eye contact, and coherent gestures of the hands. Groves adds that emotional expressivity, plus other emotional competencies such as self-awareness, emotional expressivity, self-monitoring, and empathy, are important dimensions in the broader context of emotional intelligence (EI). Stein et al. [36] support the importance of EI by stating that it is an indispensable component of leadership. Similarly, Dulewicz and Higgs [34] reflect that statements about the importance of EI for effective leadership are more than elegant phrases, and that such statements are in fact firmly established by verifiable (empirical) evidence.

Bar-On [37] states that three conceptual models dominate the field of emotional intelligence. These models are (i) the Salovey-Mayer model [38]; (ii) the Goleman model [39],[40], and (iii) the Bar-On model [41],[42]. Riggio and Reichard [43] state that the more substantive of the three models is the 'emotional abilities' model developed by Salovey, Mayer and colleagues. In the broader context of EI, Riggio and Reichard [43] state that research evidence provides substance to the conclusion that 'people skills' (the grouping of emotional and social skills) are critical for leadership effectiveness. It should also be noted that training programmes are able to improve emotional and social skills - i.e. EI can be learned and developed [43],[44].

Although not the more substantive of the three models above [43], Bailie [45] reflects that one of the first researched psychometric tests to be widely applied for EI measurement is the Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i), based on the Bar-On model. A brief description of the model follows below.

The model is based on the wider construct of emotional intelligence and social intelligence. Bar-On [37] argues that the wider construct most likely represents interrelated components of the same construct, and is more correctly referred to as 'emotional-social intelligence' (ESI).

The EQ-i referred to above measures ESI [37]. The responses of the individual result in a total emotional quotient (EQ) score plus five summarised sub-scores that measures intrapersonal, interpersonal, stress management, adaptability, and general mood competencies.

In the project management/management of projects domain, Morris [20] refers (somewhat cynically) to EI as "a salad of many other behavioural skills". Morris maintains that most of the descriptors are not easy to describe exactly, and are not established in terms of 'how' and 'when' they should be used/measured. His contention is that, to all intents and purposes, EI skills are elevated beyond their accepted levels of comprehension. The question can be asked whether there would be a different perspective if the comments were made within a sponsor rather than a project manager context. The focus on leadership is at a more elevated level in the sponsor role than in the project manager role. The sponsor role is at a strategic/tactical level, while the project manager role is at a tactical/operational level [3],[4],[5].

The debate continues in the literature about whether EI is an ability construct, a self-perception construct, or a behaviour construct. Meantime, research has found that there is a significant predictive and evidence-based relationship between EI and transformational leadership [46],[47],[34].

For the purpose of their study to determine the EI of leaders at executive management level, Stein et al. [36] use the skills- and trait-based EQ-i assessment instrument. Particular value was gained from the EQ-i method in the assessment and development of individuals who were either in an executive role or about to be promoted to an executive role. This capability of the EQ-i method regarding the role of the individual being assessed is congruent with the description of the organisational level that the designated sponsor of a megaproject would occupy. The results indicate, among other things, that it is very important for individuals to know specifically what traits and attributes are required on different occasions to perform the executive role successfully.

The leadership traits and attributes required of the executive sponsor to deal effectively with the demands of the role are described in the next section. An explanation is provided of the difference between leadership traits and attributes, attributes identified from the literature, and models used for trait identification.

5 LEADERSHIP TRAITS/ATTRIBUTES

Zaccaro et al. [48] state that significant ambiguity and confusion originates from the use of the term trait in the literature. It is often used to refer to temperament, personality, disposition, and abilities, plus any inherent qualities that the individual may have, such as physical or demographic attributes. Zaccaro [49] defines leadership traits as "Relatively coherent and integrated patterns of personal characteristics, reflecting a range of individual differences that foster consistent leadership effectiveness across a variety of group or organisational situations".

Zaccaro [49] notes that traits are traditionally referred to as 'personality attributes'. The majority of modern leader trait perspectives, with specific reference to the qualities that differentiate leaders from non-leaders, include not only personality attributes but also motives, values, cognitive abilities, social and problem-solving skills, and expertise. The Zaccaro [49] perspective is very similar to that of Yukl [50], who defines traits in the context of leadership effectiveness. In his definition, Yukl includes personality, motives, needs, and values. Zaccaro [49] also states that the latest developments on the traits and attributes of a leader include an individual's ability to change their behaviour as the situation changes. He groups the attributes in a number of integrated sets:

• Cognitive capacities that include general intelligence, cognitive complexity, and creativity;

• Personality or dispositional qualities that include adaptability, extroversion, risk propensity, and openness;

• Motives and values that include the need for socialised power, the need for achievement, and the motivation to lead;

• Social capacities that include social and emotional intelligence, and persuasion, and negotiation skills;

• Problem-solving skills that include metacognition, problem construction, solution generation, and self-regulation skills; and

• Tacit knowledge

Given how concepts are used interchangeably between traits and attributes (e.g., personality as a trait and as an attribute), it is not surprising to encounter in the literature an array of descriptors that attempt to describe the attributes of the sponsor. Other than attributes, the list includes behaviours, characteristics, skills, attitudes, factors, capabilities, abilities, and criteria.

5.1 Attributes identified from the literature

A comprehensive list of leader attributes can be compiled from the literature. A thematic grouping of the identified attributes follows:

Strategic:

• An understanding of the strategy of the organisation, the need to obtain regular updates on the strategy, and an appreciation of how the project contributes to the corporate strategy [3];

• Political knowledge of the organisation and political savvy [51],[2],[6];

• An understanding of the role, its significance, and the need to align the project with the interests of the organisation [52]; and

• Ability to provide clarity of direction (including the development of a compelling vision) within the context of the strategy and governance arrangements of the organisation [53],[54],[52].

Leadership and management:

• Ability to lead for results and success by conveying a sense of urgency and focusing on what matters most [53],[54];

• Ability to motivate the team to deliver the vision [51],[2];

• Ability to provide leadership consistent with the culture and values of the organisation [52];

• Possesses the combination of knowledge, personal attitude, and skills to fulfil the role [52];

• Ability to take a holistic view (see the big picture) and engage peers in the organisation for advice and support for key decisions [3],[4],[7];

• Ability to delegate authority to appropriate levels, and to provide ad hoc support to the project team rather than to micromanage [51],[2],[4];

• A willingness to partner with the project manager and team to deliver project objectives [4]; and

• Possesses good negotiation skills and courage, particularly in the context of providing / securing / battling for the availability of resources (financial, people or otherwise) for the project manager [52],[3],[5],[7].

Dealing with ambiguity and complexity:

• Possesses interpersonal and critical thinking skills, including the ability to work with and handle ambiguity, particularly when dealing with complex projects [51],[2],[6],[7]; and

• An understanding / willingness to explore how complexity can manifest in projects [4].

Motivation:

• Ability to engage by being willing to take personal ownership and to act in the long-term interest of the organisation (demonstrating loyalty, motivation, courage, and commitment) [52]; and

• Ability to provide motivational support for the project team when the going gets tough [4].

Communication:

• Ability to demonstrate high-level and diverse communication skills (including ability to listen and to communicate relevant organisation-wide issues to the project team) [51],[2],[6]; and

• Ability to foster an atmosphere of trust and open communication with the project manager and the project team [53],[54],[7].

Open to learning:

• Ability to foster an atmosphere of trust and open communication with the project manager and the project team [53],[54];

• Ability to exhibit a high capability for self-reflection, and willingness to engage other experts in problem-solving [4]; and

• Ability to promote knowledge creation and re-use, and being open to learning [53],[54],[7].

Networking:

• Ability to develop and foster (high-level) effective connections between and within the organisation and the project team [51],[4],[5],[6];

• Ability to demonstrate personal compatibility with other key players in the organisation [51],[2], [6];

• Ability and willingness to provide objectivity to the project team, and challenge the project assumptions (including a push to explore meaningful alternatives to maximise value) [51],[6],[7]; and

• Possesses the tenacity to break down barriers [3].

Decision-making:

• Ability and willingness to serve as a focal point for decisions beyond the scope of authority of the project manager [53],[54];

• Ability to act swiftly and decisively, and take responsibility for tough decisions [55],[53],[54],[7].

Attributes that can be obtained from experiential learning:

• An understanding of business case development, and seeking input and consensus on the contents of the business case amongst executives in the organisation [3],[7];

• An understanding of basic project management concepts, and understanding and commenting constructively at a high level on scope, risk, schedule, and cost management [4],[7];

• Ability to understand and to respond to the results of independent reviews of the project, and to hold the team accountable for such results [55],[7];

• Ability to manage self - i.e., to manage him/herself effectively within the time commitment agreed (both short- and long-term), with time management (personal and priority) being a significant part of self-management [2]; and

• Possesses sufficient knowledge of the business, its operations, market, and industry to be able to make informed decisions [3],[5],[7].

Positional attributes (not necessarily in persona of individual):

• Appropriate seniority, credibility, and (personal and positional) power within the organisation, with 'credibility' understood as being accepted by the organisation and stakeholders as suitable for the role [51],[2],[52],[6]; and

• Continuity of the sponsor on the project to be evident throughout the life cycle of the project [52].

An appraisal of the attributes listed above may suggest that one individual is unable to fulfil the whole spectrum of attributes. Remington [4] and James et al. [56] share this perspective, saying that it is possible to make provision for all the attributes, but that they rarely exist in one person. In a similar way, De Klerk [21] posits that the list of recommended leadership characteristics and traits prescribed in the literature is unrealistically comprehensive and optimistic. To achieve just some of the characteristics requires an individual with extraordinary capabilities.

As part of a larger study, the authors are exploring the executive sponsor as a key factor in megaproject success. The above listing of identified attributes is being used as a basis for the identification of important and essential attributes that are required for a megaproject's success.

Within the context of leadership trait theories and their focus on the identification of personality traits, the instruments in the next sub-section have been identified in the project management literature. These instruments are part of a broader selection of psychometric measurement tools, and indicate clear potential to assist the board/executive management in identifying a sponsor for a megaproject.

5.2 Models for leadership trait identification

Research during the 1970s revealed that the difference between the success and failure of a team is dependent not on factors such as intellect, but more on behaviour [57],[58]. Nine clusters of behaviour that individuals adopt when participating in a team (Belbin team roles) were identified.

A battery of psychometric tests underpins the model. These tests comprise measures for:

• High-level reasoning ability (the Critical Thinking Appraisal);

• Personality (the sixteen scales of the Cattell Personality Inventory or 16PF); and

• An outlook that is achieved via a Personal Preference Questionnaire (PPQ) developed specifically for the purpose [57],[58].

Remington [4] states that the Belbin Team Role Profile is particularly useful in assisting project leaders (including sponsors leading complex projects) to understand the how of compiling teams and work groups.

Bourne [5] uses the five traits in the Neuroticism-Extraversion-Openness Personality Inventory Revised (NEO-PI-R) model [59] for her discussion on leader trait theory in project management. Bourne argues that a leader can improve (with conscious effort) on these traits, in a similar way to how EI can be improved. Bourne also comments that the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) instrument is the best-known of the personality assessment tools that categorise personality.

The MBTI, developed by Katherine Briggs and Isobel Briggs Myers [64], essentially provides an indication of and measures the psychological preferences of the individual in making decisions and how he / she perceives the world. From the interactions between the preferences in the MTBI result 16 distinctive personality types. The four pairs of alternative preferences (theory of Carl Jung originally published in 1923) used in the MBTI are Introversion (I) or Extraversion (E); Sensing (S) and Intuition (N); Thinking and Feeling (F); Judging (J) and Perception (P). Morris [20] reflects that many project personnel at some time in their careers take the MBTI, or something similar.

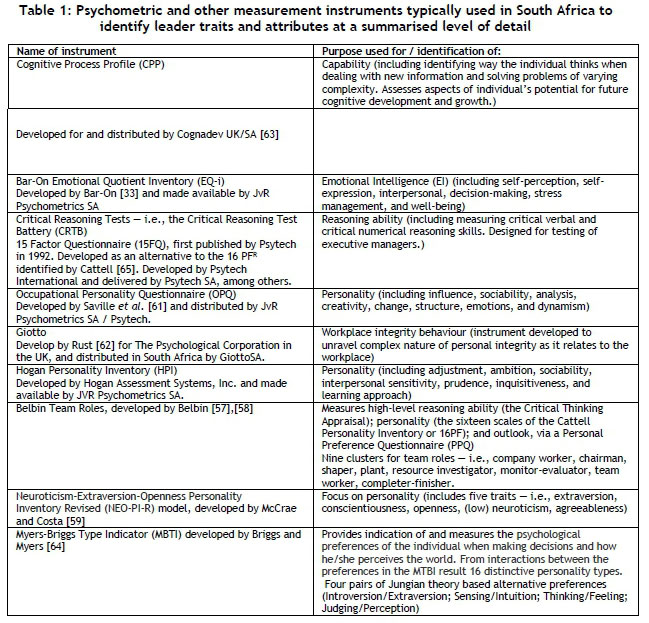

The next section brings into perspective the array of (psychometric and other) measurements instruments that are available and are being used in practice to identify the leader traits and attributes described above. The instruments were identified after engagement with two South African companies specialising (inter alia) in psychometric assessments, JvR Psychometrics and BIOSS Southern Africa. The context of the engagement with these organisations was an exploration of leadership styles/traits/emotional intelligence measurement instruments and of the potential to use these instruments to identify the leader traits / attributes of the sponsor.

6 PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS (INSTRUMENTS) FOR THE MEASUREMENT OF LEADERSHIP TRAITS / ATTRIBUTES

A representation of the different types of psychometric and other measurement instruments identified and typically used in South Africa is presented in Table 1.

It is clear from Table 1 that there are an adequate number of practical measurement instruments / tools in the psychometric assessment domain to determine the leadership traits and attributes of a leader. As an example, the Cognitive Process Profile (CPP) and Critical Reasoning Test battery (CRTB) instruments, without significant customisation, can be used to deal with the attributes that focus on critical thinking skills, ability to handle ambiguity, and dealing with complexity.

In a related perspective, PMI [60] argues that it is beneficial for an executive sponsor to perform a self-evaluation of his/her skills (to be read in the broader context of leadership styles, traits, and attributes). By inference, the authors deduce that this self-evaluation should be performed very early in the 'allocation of the sponsor to the project' action. This deduction is based on the statement in PMI [60] that the self-evaluation is even more valuable if the sponsor has a very good appreciation of sponsor requirements. This creates an opportunity for the sponsor to focus on those skills in which he/she is strong. For skills that the sponsor lacks, the assistance of specialists (in change management) should be obtained in order to address the balance of strengths and weaknesses [60].

7 CONCLUSION

The paper confirms that the sponsor on a megaproject is primarily a leader who requires an ability to ensure continually that the project remains synchronised with the strategy of the business organisation.

This paper uses leadership theories to identify instruments that can assist in the assessment of the leadership style and leader traits / attributes of a sponsor. It is found that the styles of transformational and charismatic leadership are the most appropriate for the megaproject sponsor. As indicated in Section 3.2, outstanding leadership relies significantly on the action of putting into words and feelings a viable and inspiring vision. Both styles contain the ability to develop a vision for the project that is both sufficiently compelling and powerful to align those involved with the project. The measurement instruments referred to as the MLQ Form 5X and the LBI need to be used to determine the leadership style of a designated sponsor.

In addition to the two leadership style measurement instruments, a number of measurement instruments are identified in Table 1 that can assist in identifying the leader traits and attributes of the sponsor. Collectively, a framework is thus proposed to identify assessment instruments for the leadership style and leader traits / attributes of a project sponsor.

Although the list of recommended leadership attributes identified from the literature is comprehensive, it is optimistic. It is unrealistic, however, that one individual should possess all of these attributes. Additional effort is thus needed to identify the essential attributes of a sponsor that will allow him/her to perform the role effectively.

REFERENCES

[1] Turner, R. & Müller, R. 2006. Choosing appropriate project managers: Matching their leadership style to the type of project. Newtown Square, Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute. [ Links ]

[2] Crawford, L., Cooke-Davies, T., Hobbs, B., Labuschagne, L., Remington, K. & Chen, P. 2008. Governance and support in the sponsoring of projects and programs. Project Management Journal, 39 (Supplement), August, S43-S55. [ Links ]

[3] West, D. 2010. Project sponsorship: An essential guide for those sponsoring projects within their organisations. Farnham: Gower. [ Links ]

[4] Remington, K. 2011. Leading complex projects. Farnham: Gower. [ Links ]

[5] Bourne, L. 2015. Making projects work - Effective stakeholder and communication management. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. [ Links ]

[6] Van Heerden, F., Steyn, J. & van der Walt, D. 2015. Programme management for owner teams: A practical guide to what you need to know. Sasolburg, South Africa: Owner Team Consult. [ Links ]

[7] Barshop, P. 2016. Capital projects: What every executive needs to know to avoid costly mistakes and make major investments pay off. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [ Links ]

[8] Project Management Institute (PMI). 2018. Pulse of the profession in-depth report: Success in disruptive times - Expanding the value delivery landscape to address the high cost of low performance. Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, Inc. [ Links ]

[9] Project Management Institute (PMI). 2017. A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOKguide), 6th edition. Pennsylvania. Project Management Institute, Inc. [ Links ]

[10] International Project Management Association (IPMA). 2015. IPMA Competence Baseline (ICB) (Version 4). Amsterdam: International Project Management Association. [ Links ]

[11] Association for Project Management (APM). 2012. APM Body of Knowledge, 6th edition. Buckinghamshire: Association for Project Management. [ Links ]

[12] The Office of Government Commerce. 2007. Managing successful programmes, 2nd edition. Including Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2, 2005. London: The Stationary Office. [ Links ]

[13] Flyvbjerg, B. 2014. What you should know about megaprojects and why: An overview. Project Management Journal, 45, 6-19. [ Links ]

[14] Project Management Institute (PMI). 2014. Pulse of the profession in-depth report: Executive sponsor engagement - Top driver of project and program success. Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, Inc. [ Links ]

[15] Stacey, R.D. 1996. Complexity and creativity in organizations. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [ Links ]

[16] Chapman, R.J. 2016. A framework for examining the dimensions and characteristics of complexity inherent within rail megaprojects. International Journal of Project Management, 34(6), 937-956. [ Links ]

[17] Whitty, S.J. & Maylor, H. 2009. And then came complex project management (revised). International Journal of Project Management, 27(3), 304-310. [ Links ]

[18] Maylor, H., Vidgen, R. & Carver, S. 2008. Managerial complexity in project-based operations: A grounded model and its implications for practice. Project Management Journal, 39(S1), S15-S26. [ Links ]

[19] Yukl, G. 1989. Managerial leadership: A review of theory and research. Journal of Management, 15(2), 251-289. [ Links ]

[20] Morris, P.W.G. 2013. Reconstructing project management. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

[21] De Klerk, M. 2014. Project management or project leadership? In Y du Plessis (ed.), Project management: A behavioural perspective (pp. 61-96). Cape Town: Pearson. [ Links ]

[22] Turner, J.R. 2017. Leadership and governance on projects. PM Concepts. [Online] Available: https://www.projecthalfdouble.dk/en/download/News/15/170228-half-double-morning-meeting-7-ralf-muller-slides-v03.pdf. Accessed: 27 March 2018. [ Links ]

[23] Hernandez, M., Eberly, M.B., Avolio, B.J. & Johnson, M.D. 2011. The loci and mechanism of leadership: Exploring a more comprehensive view of leadership theory. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(6), 1165-1185. [ Links ]

[24] Sparrowe, R.T. & Liden, R.C. 2005. Two routes to influence: Integrating leader-member exchange and social network perspectives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(4), 505-535. [ Links ]

[25] Yukl, G. 2011. Contingency theories of effective leadership. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson & M. Uhl-Bien (eds). The SAGE handbook of leadership (pp. 286-298). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. [ Links ]

[26] Antonakis, J., Fenley, M. & Liechti, S. 2011. Can charisma be taught? Tests of two interventions. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 10(3), 374-396. [ Links ]

[27] Judge, T.A., Woolf, E.F., Hurst, C. & Livingston, B. 2006. Charismatic and transformational leadership: A review and an agenda for future research. Zeitschrift fur Arbeits- u. Organisationpsychologie, 50(4), 203-214. [ Links ]

[28] Bass, B.M. & Avolio, B.J. 1993. Transformational leadership: A response to critiques. In M.M. Chemmers & R. Ayman (eds), Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions. Orlando: Academic Press. [ Links ]

[29] Diddams, M. & Chang, G.C. 2012. Only human: Exploring the nature of weakness in authentic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 23, 593-603. [ Links ]

[30] Bass, B.M. & Avolio, B.J. 1997. Full range leadership development: Manual for the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Palo Alto, California: Mindgarden. [ Links ]

[31] Spangenberg, H.H. & Theron, C.C. 2002. Development of a uniquely South African leadership questionnaire. South African Journal of Psychology, 32(2), 9-25. [ Links ]

[32] Groves, K.S. 2006. Leader emotional expressivity, visionary leadership, and organisational change. Leadership and Organisation Development Journal, 27(7), 566-583. [ Links ]

[33] Yukl, G. 1999. An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 285-305. [ Links ]

[34] Dulewicz, V. & Higgs, M.J. 2004. A new instrument to assess leadership dimensions and styles. Selection and Development Review, 20(2), 7-12. [ Links ]

[35] Dinh, J., Lord, R., Garnder, W., Meuser, J., Liden, R.C. & Hu, J. 2014. Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: Current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), 36-62. [ Links ]

[36] Stein, S.J., Papadogiannis, P., Yip, J.A. & Sitarenios, G. 2008. Emotional intelligence of leaders: A profile of top executives. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal, 30(1), 87-101. [ Links ]

[37] Bar-On, R. 2006. The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psichotherma, 18, 13-25. [ Links ]

[38] Mayer, J.D. & Salovey, P. 1997. What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. Sluyter (eds), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Implications for educators (pp. 3-31). New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

[39] Goleman, D. 1998a. Working with emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books. [ Links ]

[40] Goleman, D. 1998b. What makes a leader? Harvard Business Review, November-December, Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. [ Links ]

[41] Bar-On, R. 1997. The Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i): Technical manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems, Inc. [ Links ]

[42] Bar-On, R. 2000. Emotional and social intelligence: Insights from the Emotional Intelligence Inventory (EQ-i). In R. Bar-On & J.D.A. Parker (eds): Handbook of emotional intelligence. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

[43] Riggio, R.E. & Reichard, R.J. 2008. The emotional and social intelligences of effective leadership: An emotional and social skill approach. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(2), 169-185. [ Links ]

[44] Ashkanasy, N.M. & Dasborough, M.T. 2003. A study of emotional awareness and emotional intelligence in leadership teaching. Journal of Education for Business, 79(1), 19-22. [ Links ]

[45] Bailie, K. 2005. An exploration of the utility of a self-report emotional intelligence measure. Thesis research paper for Degree of Master of Arts (Industrial Psychology). Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

[46] Mandell, B. & Pherwani, S. 2003. Relationship between emotional intelligence and transformational leadership style: A gender comparison. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(3), 387-404 [ Links ]

[47] Boyatzis, R.E., Batista-Foguet, J.M., Fernandez-i-Marin, X. & Truninger, M. 2015. EI competencies as a related but different characteristic than intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(72), 1-14. [ Links ]

[48] Zaccaro, S.J., Kemp, C. & Bader, P. 2004. Leader traits and attributes. In J. Antonakis, A.T.Cianciolo and R.J. Sternberg (eds), The nature of leadership (pp. 101-124). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. [ Links ]

[49] Zaccaro, S.J. 2007. Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1), 6-16. [ Links ]

[50] Yukl, G. 2006. Leadership in organizations (6th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

[51] Helm, J. & Remington, K. 2005. Effective project sponsorship: An evaluation of the role of the executive sponsor in complex infrastructure projects by senior project managers. Project Management Journal, 36(3), September, 51-61. [ Links ]

[52] Association for Project Management (APM). 2009. Sponsoring change: A guide to the governance aspects of project sponsorship. APM Knowledge Specific Interest Group, Buckinghamshire. [ Links ]

[53] Englund, R.L. & Bucero, A. 2006. Project sponsorship: Achieving management commitment for project success. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

[54] Bucero, A. & Englund, R.L. 2007. Building executive support - keys to project success. Paper delivered at the 2007 PMI Global Congress, Budapest. [ Links ]

[55] Pacelli, L. 2005. Top ten attributes of a great project sponsor. Paper delivered at the 2005 PMI Global Congress, Toronto. [ Links ]

[56] James, V., Rosenhead, R. & Taylor, P. 2013. Strategies for project sponsorship. Virginia: Management Concepts Press, Inc. [ Links ]

[57] Belbin, R.M. 2010a. Management teams: Why they succeed or fail. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

[58] Belbin, R.M. 2010b. Team roles at work. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. [ Links ]

[59] McCrae, R.R. & Costa, P.T. 1997. Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52, 509-516. [ Links ]

[60] Project Management Institute (PMI). 2014. Pulse of the profession in-depth report: Executive sponsor engagement - Top driver of project and program success. Pennsylvania: PMI, October. [ Links ]

[61] Saville, P., Sik, G., Nyfield, G., Hackston, J. & Maclver, R. 1996. A demonstration of the validity of the Occupational Personality Questionnaire (OPQ) in the measurement of job competencies across time and in separate organisations. Applied Psychology, 45, 243-262. [ Links ]

[62] Rust, J. 1999. The validity of the Giotto integrity test. Personality and Individual Differences, 27, 755768. [ Links ]

[63] Prinsloo, M. & Barrett, P. 2013. Cognition: Theory, measurement, implications. Integral Leadership Review, June, 1-47. [ Links ]

[64] Percival, T.Q., Smitheram, V. & Kelly, M. 1992. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and conflict-handling intention: An interactive approach. Journal of Psychological Type, 23, 10-16. [ Links ]

[65] Cattell, R. B. 1946. Description and measurement of personality. Oxford: World Book Company. [ Links ]

Available online 9 Nov 2018

* Corresponding author: willeml@sun.ac.za

# The author was enrolled for a PhD (Business Management & Administration) degree at the University of Stellenbosch Business School, South Africa