Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

versão On-line ISSN 2224-7890

versão impressa ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.29 no.3 Pretoria Nov. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7166/29-3-2057

SPECIAL EDITION

Leadership styles in projects: current trends and future opportunities

S. Pretorius*, #; H.Steyn; T.J. Bond-Barnard

Department of Engineering and Technology Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Currently, many organisations experience challenges as a result of uncertainty, fast-changing environments, globalisation, and increasingly complex work tasks. In order to adapt to these challenges, a shift in leadership style may be needed. Traditionally, leadership has been seen as a vertical relationship (top-down influence). For a number of decades, this vertical leadership model has been the principal one in the leadership field; but lately, shared and balanced leadership have gained importance, especially in the project management literature. This theoretical study highlights some differences between 'leadership' and 'management', and explores current trends in the leadership literature. It especially focuses on vertical, shared, and balanced leadership in project management, and identifies future opportunities for research.

OPSOMMING

Baie organisasies ervaar vandag uitdagings as gevolg van onsekerheid, vinnig-veranderende omgewings, globalisering, en toenemend komplekse werkstake. 'n Verskuiwing in leierskapstyl mag nodig wees om aan te pas by hierdie uitdagings. Tradisioneel was leierskap gesien as 'n vertikale verhouding (bo-na-onder invloed), en hierdie vertikale leierskapsmodel was die vernaamste een in die leierskapsveld vir baie jare. Gedeelde en gebalanseerde leierskap het onlangs begin om belangrik te word, veral in die projekbestuursliteratuur. Hierdie teoretiese studie bespreek sommige verskille tussen leierskap en bestuur, en ondersoek die onlangse rigtings in die leierskapsliteratuur. Dit fokus veral op vertikale, gedeelde, en gebalanseerde leierskap in projekbestuur, en identifiseer toekomstige geleenthede vir navorsing.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, the general perception of an organisation as a 'machine', in which leaders at the top of the hierarchy direct and control processes, has changed [1]. In its place, the organisation can be seen as a dynamic system of interrelated relationships and networks of influence. In order to accommodate this paradigm shift in thinking about the organisation, a change in the concept of leadership has also taken place [1].

The increasing application of empowered teams, coupled with the flattening of organisational structures, results in the need for a shift in the more traditional models of leadership [2]. Turner and Müller [3] demonstrate that leadership is a critical success factor for projects. Müller et al. [4] state that research on project leadership is becoming increasingly important for project management as a profession. Studies on balanced leadership are limited, and are not linked to a general framework that would allow scholars to theorise about it or practitioners to use it deliberately to the advantage of their projects [5].

Traditionally, leadership has been perceived as a single individual (the formally appointed leader) leading a number of subordinates or followers. This relationship has been a vertical one of top-down influence that could also be called 'vertical' leadership. For a number of decades, this leadership model has been the principal one in the leadership field. Recently however, researchers have challenged this notion [6]. New models of leadership have emerged, leading to the so-called 'post-heroic' or shared leadership approach. The intention of this innovative approach to leadership is to transform organisational practices, structures, and interdependencies. This evolving leadership model holds that effective leadership does not depend on individual, heroic leaders, but rather on leadership practices at different levels within the organisational hierarchy, as it is a group-level phenomenon [1,4].

The objective of this study is to contribute to the body of knowledge in the field of leadership pertaining to project management. This study is intended for both scholars and practitioners, as it aims to provide them with new insights into current trends in the literature pertaining to leadership - specifically, vertical and shared leadership - and future opportunities for research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

We start the literature review with a brief history of the development of leadership theory and terminology.

2.1 Leadership theories: A brief history

For more than a century, 'leadership' has been a focus of academic introspection. Finding a definition for the term has proved to be challenging for researchers and practitioners alike, and no consensus has been reached [7]. Barker [8] says that everyone generally knows what leadership is, until asked to define it. The word 'leadership' has different meanings for different people. Modern leadership theories started to develop during the Industrial Revolution, when mainly economists started paying attention to it [9]. The industrial-era leadership theories were based on the hierarchical outlook adopted by the early Christian Church, which believed that leadership was centralised in the person at the top of the hierarchy and in that individual's excellent qualities and abilities to manage his subordinates, as well as the activities of this person in relation to goal achievement [8].

Definitions of leadership have evolved constantly during the past decade [7]. Rost [10] studied material written from 1900 to 1990, and found more than 200 different definitions for leadership. It became increasingly clear to scholars that it is probably impossible to devise one common definition of leadership, due to such factors as growing global influences and generational differences. Leadership may continue to mean different things to different people [7].

Despite the diverse number of ways in which leadership has been conceptualised, there are certain components that are most frequently central to the phenomenon. They are the following [7]:

• Leadership is a process - i.e., a transactional occurrence that takes place between leaders and followers. "The leader affects and is affected by followers". Leadership is not limited to a designated leader, but is available to everyone.

• Leadership encompasses influence - i.e., how the leader affects followers. It is a continuous social process [8].

• Leadership takes place in groups - i.e., a leader influences a group of individuals who have a common purpose.

• Leadership involves common goals - i.e., leaders and followers have a mutual purpose.

• Leadership is not the property of the project manager, but instead a property of the project itself [11].

• Leadership is both an individual and an institutional trait [12].

2.2 Leadership approaches, theories, and styles

A number of leadership approaches, theories, and styles have featured in the literature in the past couple of decades. All of them have their strengths, weaknesses, and criticisms, which will not be covered in this study due to scope limitations. These approaches, theories, and styles briefly include, but are not limited to, the following:

2.2.1 Trait approach

This methodology is built on the theory that people are born with certain traits that make them great leaders. The instinctive leadership talents of great social, political, and military leaders (e.g., Abraham Lincoln, Mohandas Gandhi, and Napoleon Bonaparte) were identified and used to determine the specific traits that separated leaders from followers [7].

2.2.2 Skills approach

Leadership skills are those abilities that can be acquired and developed through practice and training. They can be further divided into technical skills and human skills, and include problemsolving skills, social-judgement skills, and knowledge [13].

2.2.3 Behavioural approach

In this approach, it is believed that leaders are responsible for shaping an environment that empowers followers to realise specific tasks. In other words, leaders can manage their subordinates' behaviour through staging antecedents and consequences of behaviour. There is a dynamic, mutual interaction between the leader, the follower, and the environment. Environmental factors include technology, organisational structure, type of task, and the size of the organisation [14].

2.2.4 Situational approach

Hersey and Blanchard developed this approach in 1969, and it focuses on the principle that different situations demand different kinds of leadership. Leadership comprises both a directive and a supportive dimension, and each has to be applied in a particular situation. The core of the situational approach requires that leaders match their style (directive or supportive) to the competence and commitment of the followers [7].

2.2.5 Psychodynamic approach

This model uses one principal central concept, that of personality, which is defined as a constant pattern of thinking, feeling, and acting toward the environment, which also includes other people. This approach therefore concentrates on the personalities of leaders and subordinates [13].

2.2.6 Path-goal theory

According to this theory, effective leaders influence their followers' motivation, ability to perform well, and satisfaction. This theory focuses mainly on how the leader affects his/her followers' perception of their work, personal goals, and paths to goal realisation. The leader's behaviour should increase subordinate goal achievement and illuminate the paths to these goals [15].

2.2.7 Leader-member exchange theory

This theory focuses on the relationship between leader and follower. The leaders develop individualised relationships with each of their subordinates, and leadership becomes apparent when leaders and followers are able to establish real interactions that result in reciprocal and incremental influence [16].

2.2.8 Strategic leadership

This type of leadership focuses on how executive leaders influence organisational performance, thus addressing leadership occurrences at the upper levels of organisations [17].

2.2.9 Transformational leadership

Avolio, Walumbwa and Weber [16] define transformational leadership as "leader behaviours that transform and inspire followers to perform beyond expectations while transcending self-interest for the good of the organisation". This type of leadership includes the four aspects of idealised influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual motivation, and individualised attention [13]. An example of transformational leadership in an organisation would be a manager who tries to change his/her company's corporate values "to reflect a more humane standard of fairness and justice". While doing this, both manager and subordinates may develop higher and stronger moral values [7]. This leadership type is primarily people-focused [3].

2.2.10 Transactional leadership

The bulk of the leadership models can be categorised under transactional leadership, which centres on the interactions that occur between leaders and subordinates. It occurs when managers offer promotions or financial incentives to employees who exceed their goals [7]. This leadership type is largely task-focused [3].

2.2.11 Servant leadership

Servant leaders want to serve by ensuring that their followers' highest priority needs are being served. They place the good of their followers over their own self-interests, and exhibit strong moral behaviour [7]. Servant leadership can be viewed as a trait or a behaviour [13].

2.2.12 Authentic leadership

Here the main emphasis is on the leader's genuineness (authenticity/truthfulness). The leader is transparent, and exhibits ethical behaviour that promotes openness in sharing the information needed to make decisions while taking followers' contributions in consideration. Authentic leadership is collectively viewed in three diverse conducts: intrapersonal, developmental, and interpersonal [13,16]. This leadership style centres around trust, and is motivated by the well-being of the followers [18].

2.2.13 Charismatic leadership

This type of leadership arises in times of distress, uncertainty, or extreme enthusiasm, and exists in a range of social relationships. It is powered by emotion and the frantic commitment of followers. The charismatic leader can arise from outside of the formal organisational hierarchy, and does not need to be an appointed leader. Charisma is seen as a talent that is innate to an individual. Charismatic leaders usually disappear suddenly once their inborn talents are no longer needed or when they no longer exist [19].

2.2.14 Laissez-faire

A laissez-faire leader typically circumvents making decisions, delegates responsibility, and does not enforce authority [3].

Pearce and Wassenaar [20] are of the opinion that all the above labels are "simply the proverbial old wine in new skins". They state that shared leadership incorporates all of these terms, and that it provides a way to organise and make sense of them. They define 'shared leadership' as a meta-theory of leadership, meaning that all leadership is shared leadership. It is just the degree that differs: sometimes leadership is shared completely, while at other times it is not shared at all. Zhu et al. [21] say that almost any type of leadership can be shared, and that shared leadership is regarded as "meta-level leadership". This study will use the above definition of Pearce and Wassenaar [20], for whom shared leadership is seen as a form of leadership that encompasses all leadership styles, theories, and approaches. Thus leadership can be seen as a continuum between vertical and shared leadership, where there could be different balances with vertical leadership on the one extremity and shared leadership on the other.

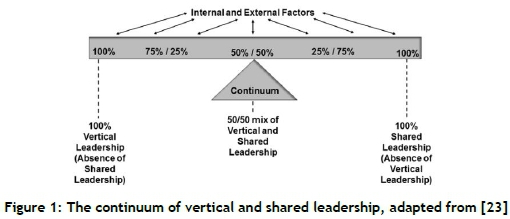

We define 100 per cent vertical leadership as the absence of shared leadership, and 100 per cent shared leadership as the state in which there is no vertical leadership. There could also be a 50/50 balance between the two leadership styles. Figure 1 illustrates the continuum between vertical and shared leadership. Internal and external factors could influence the balance between these two leadership styles, but that is beyond the scope of this study.

2.3 Definition of leadership

A number of definitions of leadership exist in modern theory, but in order to limit the scope of this study, the following definition is used: "Leadership can be seen as the practice of influencing others to agree about how work should be done effectively, and the process of enabling individual and collective efforts to accomplish a shared objective" [22,23].

2.4 Leadership and management: Differences and similarities

There is a general perception that the most important skill of leaders is their ability to manage [24]. Although leadership and management are similar and overlap in many ways, there are also fundamental differences between the two concepts. For example, if an organisation has strong management but weak leadership, the outcome tends to be rigid and bureaucratic. On the other hand, if an organisation has strong leadership without strong management, the outcome could be pointless or "misdirected change for change's sake" [7]. Knox et al. [25] point out that managing without leading and investing in the team, and failing to delegate decision-making power to the lowest possible level, are two of the biggest mistakes that can hamper the delivery of exceptional project outcomes in ultra-large projects. They continue by saying that, although leadership skills are frequently termed 'soft', in reality they can be the most challenging elements to instil within a capital project organisation [25]. "The soft stuff is the hard stuff." It is therefore important briefly to investigate what the current literature says about management versus leadership. Leadership cannot be investigated in the absence of management.

Both leadership and management entail the following [7,24]:

• They involve influence.

• They require working with people.

• They are concerned with effectively accomplishing goals.

• Both management and leadership are crucial if an organisation is to be successful. To be prosperous and effective, an organisation needs to nurture both competent management and skilled leadership.

The differences between leadership and management are outlined in Table 1.

For the purposes of this study, we focus on the leadership process.

2.5 Leadership in project management

In his seminal article, published in the Harvard Business Review in 1959, Paul O. Gaddis defined the undertaking of being a project manager, which was a relatively new concept at that stage [26]. He identified a number of important characteristics that a successful project manager needs to possess in order to manage projects that perform well. An example of these characteristics is that a project manager needed to have the ability to handle both technological research and business matters at the same time, and had to advance the project process, taking into consideration both the project team and the external stakeholders. Basically, the project manager had to be 'a Jack of all trades'. From the start, project management was thus labelled as a new kind of leadership task, compared with existing ones [26]. Traditionally, a person-centred approach was taken in the management of projects. The emphasis was given to the role of the project manager (vertical, formal appointed leader) in achieving project objectives and outcomes [4].

Current studies demonstrate that leadership in projects is dependent on aspects that are not considered in traditional leadership theories (e.g., constant in-flow and out-flow of specialists and teams when the situation warrants it). Today, the role of leadership is progressively gaining more interest in project management research. In the year 2000, twenty-six research articles referred to the terms 'lead' and 'project management' in their titles, while the use of these terms grew to 271 in 2015 [4]. According to Müller et al. [4], two major trajectories of leadership emerged out of these articles: the traditional vertical leadership track (with an appointed or formal leader of a team), and the shared/horizontal (person-centred) stream. These two major leadership streams/tracks will be discussed further in this paper.

Today, a great number of organisations experience challenges arising from uncertainty, fast-changing environments, globalisation, and increasingly complex work tasks. Organisations typically adapt to such change by reorganising their work, using team-based structures [27]. In the light of this, the question about how best to lead the team-based structures arises. Scholars have proposed that the shared leadership approach possibly provides a more appropriate answer to team management than traditional, hierarchical (or vertical) leadership, as embodied by the typical solo-appointed-leader approach [27,28].

2.6 Vertical leadership

Leadership is frequently described as more 'vertical' when an organisational hierarchy is in place [23]. In such a hierarchy, a leader is formally appointed to function as the main source of instruction, oversight, and control for his/her subordinates. In most cases, these vertical leaders influence projects in a downward, 'one-to-many' style [23,29,30]. This kind of leadership is viewed primarily as an input to team processes and performance: the team leader's (vertical leader's) skills, abilities, behaviours, and personal characteristics are thought to affect team processes and performance directly [28].

Müller et al. [5] define vertical leadership as "the interpersonal process through which the project manager influences the team and other stakeholders to carry the project forward". In principle, the project manager (formally appointed vertical leader) oversees the activities of the team, and the team executes the orders of the leader [23]. The vertical leader is the main source of information for team members, which implies, in its extreme form, that other team members do not have the opportunity to evaluate information and reach consensus about a decision made by a superior. Team members merely follow orders [22]. The relationship between the leader and his/her followers is a top-down influence, and this model of leadership has been the most prominent one in the leadership field for many decades [6]. As stated earlier in this article, vertical leadership can be defined as the absence of shared leadership.

2.6.1 Project managers as vertical leaders

According to Müller et al. [5], project managers are both managers and leaders. They have both authority and accountability to deliver vertical leadership for the project team. In their role as managers, they are responsible for conducting and achieving project objectives, and as leaders they influence, guide, and direct team members. In these roles, they tend to use transactional leadership in simpler projects, while for more complex projects, transformational leadership styles are practised [5,31,32].

2.7 Shared leadership

Since the mid-1990s, the theme of shared leadership has received considerable attention in the research community [33,34]. In recent years, some scholars have confronted the more traditional form of leadership (vertical leadership) by stating that leadership is an activity that can be shared among team members of a team or organisation [6]. Pearce and Conger [6] define shared leadership as a "dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of team or organisational goals or both". They state that two types of influence are generally involved: peer (shared/horizontal) guidance, and upward or downward hierarchical influence. Thus the key difference between shared/horizontal and the more traditional types of leadership is that teams are influenced by more than just the downward influence on followers (subordinates) by a formally appointed leader. Leadership is largely dispersed among a set of individuals [6].

Müller [30] says that in shared leadership there is a supportive state of mutual influence such that the leadership role emerges from individuals in the team. All team members participate in the decision-making process (collaborative decision-making), they perform duties that the vertical leader would traditionally have done, share accountability for outcomes, and, when necessary, offer direction to other team members to achieve group goals [35,36]. Duties and responsibilities are cooperatively shared by the team members [12]. Shared leadership entails that team members have substantial power to direct the team's forward path [37].

In a multifaceted team environment, an individual vertical leader (project manager) is less likely than the team as a whole to possess the knowledge and abilities needed to lead the team effectively [37]. Shared leadership attempts to solve this phenomenon through team members recommending a specific team member to take over the leadership role at a specific point in time [23,30]. In a typical project management environment, different skills and expertise are needed at different points in the project life cycle. Shared leadership is practised when the leadership role is shifted between team members with the necessary skills, as dictated by either environmental needs and demands, or the developmental stage of the team at any given time [38,39]. When the situation warrants it, team members volunteer to provide the required leadership, based on their skills, and then step back to allow others to assume the leadership role [7]. This transfer of leadership may happen many times while advancing towards goal achievement or the completion of a project [38]. Shared leadership is more likely to be present in voluntary or empowered teams [2].

Shared leadership displays the following characteristics [21,40]:

• Constant teamwork.

• Ad hoc, emergent, and informal.

• A group focus.

• Sharing of information between team members.

• All team members are equal and interdependent.

• Independence is frowned on.

• Each team member influences the others equally.

• Joint decision-making.

• Team members have social skills.

2.7.1 The implementation of shared leadership

The vertical leader's actions are frequently critical to the implementation process. They should specifically involve the following [41]:

• Selecting suitable team members.

• Forming team norms that are supportive of shared leadership.

• Coaching and developing team members' leadership skills.

• Empowering team members to self-lead.

• Be a role-model for self-leadership behaviours.

• Boosting team problem-solving and decision-making.

Conger and Pearce [41] conclude by saying that they suspect that there could be a much broader collection of contributing factors, such as organisational culture, incentives, performance management systems, organisational structure, job assignments, and senior management attitudes towards leadership.

2.8 Horizontal leadership

To date there has been limited use of the term 'horizontal leadership' and little discussion of the difference between horizontal and shared leadership, probably as a result of the novelty of this phenomenon [23]. Müller [30] explains that horizontal leadership is practised by a team member after he/she has been nominated by the project leader (vertical leader). The project manager governs this leadership for the duration of the nomination. Müller [30] adds that horizontal leadership has a closer connection with vertical leadership than described in the traditional shared leadership theories. By contrast, shared leadership is a cooperative action, and shifting control to the most suitable team members is necessary [39].

Horizontal leadership recognises the distributed form of leadership in projects. This implies that one or several team members influence the project manager, and the rest of the team complete the project in a set manner [39]. Because specific skills are needed at a certain point in time, team members become temporary leaders, based on their skills and capabilities. They temporarily take over the leadership role on behalf of the project manager (vertical leader) [5]. The vertical leader is responsible for constantly maintaining horizontal leadership by keeping the general vision and direction, encouraging the shift between vertical and horizontal leadership by including the team in the pursuit of solutions, and managing the fairness of the leadership assignments [5]. Horizontal leadership is facilitated through empowerment by the project manager, and is accomplished through self-management of the team [39].

2.9 The difference between shared and horizontal leadership

Shared leadership is closely connected to horizontal leadership, and complementary to vertical leadership in balanced leadership [18]. The difference between shared and horizontal leadership is summarised in Table 2.

In both shared and horizontal leadership, the leadership role constantly shifts between team members, based on the crucial expertise needed at different points in time [4,42].

2.10 The appropriate balance between vertical and shared leadership

We acknowledge the differences between shared and horizontal leadership, as set out in Table 2. However, in order to limit the scope of this paper, and due to the limited use of the notion of horizontal leadership in the literature, no distinction will be made between these two styles in the rest of this paper. 'Shared leadership' will be used to refer to both of these leadership styles.

While some scholars view vertical and shared leadership as essentially separate styles, shared leadership is not a substitute for hierarchical leadership (vertical leadership). Organisations should not be forced to choose between vertical and shared leadership, as the two concepts complement each other [43]. The occurrence of shared leadership is typically demonstrated in technical decisions, as team members have the best knowledge about how to address these issues. On the other hand, strategic decisions are usually formulated by the project manager (vertical leader), and are often escalated to more senior leaders for decisions [39]. No single individual has the ability competently to perform all possible leadership roles within a group or organisation. Additionally, the vertical leader may have preferences for certain leadership tasks and not for others. Today, most teams have multifunctional and highly-skilled team members who have strong leadership skills. It is therefore logical to supplement the vertical leader's weak points and disinclinations towards leadership with the individual members' strengths in the chosen areas [41].

Project teams are often under a steady process of restructuring, and therefore have little chance to develop and mature in the sense of traditional leadership theories. Previous studies have indicated that leadership in projects is neither exclusively executed by the project manager, nor fully performed by the team or some of its members [5]. Although the leadership responsibility rests formally with the project manager, it is regularly delegated to specialists to lead temporarily in order to solve a technical or other issue, and then handed back to the project manager. A contemporary stream of literature defines this action as 'balanced leadership' [5,18].

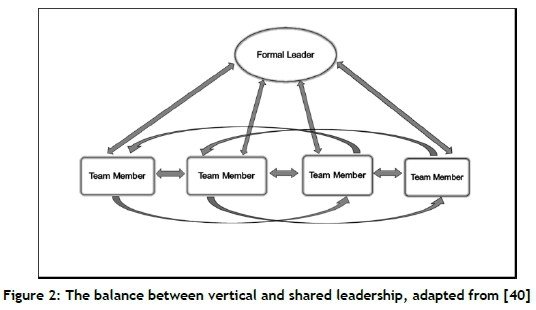

Shared leadership frequently supplements and enhances, but does not replace, vertical leadership [44]. Figure 2 demonstrates an integrated model that clarifies the relationship between vertical and shared leadership. It illustrates real leadership, and lays out directions of influence. It can be seen that there is leadership from the top down (vertical leadership), but also upwards (from the bottom up), and between the team members (shared leadership) [40].

Projects seldom depend on only one or the other form of leadership; most of the time a combination of vertical and shared leadership is used [4]. As mentioned previously, there is a continuum between vertical and shared leadership (see Figure 1 ): there should be an appropriate balance where the leadership style should be tailored, based on the specific internal and external circumstances [45].

3 FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND OPPORTUNITIES

The individual-based 'heroic' models of leadership may no longer be viable, as "organisations are moving into a knowledge driven era where firms are distributed across cultures". Shared leadership could be more suitable, and it should be further examined [16,46]. The field of shared leadership is still in its initial stages, as very few empirical studies have been published to date [6]. Avolio et al. [16] envisage that more theoretical work and empirical studies will focus on the follower (subordinate) as a crucial part of the leadership dynamic [16].

Clarke [11] states that little research has been conducted to identify the conditions when shared leadership might be more effective than vertical leadership in projects. The factors that might be favourable to shared leadership should also be investigated. Although he addressed some of these issues in his research, and a number of studies have been conducted on the topic since 2012 [4,30,34,39,44,47,48], there is still a considerable gap in the knowledge base of leadership in project management that needs to be addressed. This could be an opportunity for future research.

Conger and Pearce [41] state that there are at least seven areas of opportunity for future research:

• The relationship between shared and vertical leadership.

• The more subtle dynamics of how leadership is shared in group and organisational settings.

• How to introduce shared leadership to a team successfully.

• The outcomes associated with shared leadership in groups.

• Measurement of the phenomenon of shared leadership.

• Cross-cultural influences.

• The liabilities of shared leadership.

The education and training of project managers should address the dynamic nature of leadership within a broader systems perspective of projects. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to develop a new model of shared leadership processes that is of practical value to project managers [11].

Project management research only recently began to study the notion of balanced leadership, which combines the concepts of shared and vertical leadership and focuses on the dynamics of their interactions. This is an opportunity for further research [5].

4 CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

Jack Futcher says: "Process does not deliver projects. Leadership does, and has to trump process. " [25].

This paper investigates the current trends and future opportunities of leadership styles in project management, and identifies a gap in the project management literature pertaining to leadership.

Since the mid-1990s, the theme of shared leadership has received considerable attention in the research community, and the roles of leadership, and shared leadership in particular, are progressively gaining more interest in project management research [4,33,34]. The term 'horizontal leadership' has recently begun to appear in the literature [4,5,30,36,39,42,45,49]. A contemporary stream of literature investigates balanced leadership [30]. It is clear that leadership trajectories are moving away from the traditional form of vertical leadership - with one formally appointed leader - in favour of a more shared, distributed, horizontal, and balanced leadership approach.

The fact that many projects fail due to problems of leadership within the projects could be a consequence of the practice of employing project managers predominantly for their technical expertise rather than for their leadership abilities [50]. Today most project teams consist of highly skilled and educated individuals who are capable of taking over leadership functions when needed. This could be a good basis for shared leadership [11].

The project characteristics (project-related factors) that could influence the leadership style of the project manager and team members (shared and/or vertical leadership) have been neglected to a large extent in recent studies. This is a gap in the literature, and it should be addressed in order to develop much-needed practical models for project management scholars and practitioners alike.

Project-related factors could include, but are not limited to, the following: [23].

• Organisational project management maturity.

• The project's position/level within the hierarchy of work in a project-oriented organisation.

• Organisational structure (functional, matrix, or projectised).

• Type of project in terms of level of technological uncertainty, novelty, complexity, and scope.

• The stage in the project life-cycle.

• Level of trust and collaboration between team members.

The shared leadership field is brimming with research opportunities for scholars, and an extensive gap in the knowledge base of project management leadership still exists [11,41]. Pearce and Conger [6] predict that shared leadership will not merely be "another blip on the radar screen" of organisational science. Shared leadership's time has arrived, and scholars should exploit this further.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partly funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF).

REFERENCES

[1] Fletcher, K. and Käufer, J.K. 2003. Shared leadership, in Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Pearce, J.A. and Conger, C.L. (eds), Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 21-47. [ Links ]

[2] Pearce, C.L. and Sims, H.P. 2002. Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: An examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice, 6(2), pp. 172-197. [ Links ]

[3] Turner, J.R. and Müller, R. 2005. The project manager's leadership style as a success factor on projects: A literature review. Project Management Journal, 36, pp. 49-61. [ Links ]

[4] Müller, R., Niklova, N., Sankaran, S., Hase, S., Zhu, F., Xu, X., Vaagaasar, A.L. and Drouin, N. 2016. Leading projects by balancing vertical and horizontal leadership - International case studies, in EURAM 2016 Conference. [ Links ]

[5] Müller, R., Sankaran, S., Drouin, N., Vaagaasar, A.L., Bekker, M.C. and Jain, K. 2017. A theory framework for balancing vertical and horizontal leadership in projects. International Journal Project Management, in press. [ Links ]

[6] Pearce, J.A. and Conger, C.L. 2003. All those years ago, in Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Pearce, J.A. and Conger, C.L. (eds), Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 1-18. [ Links ]

[7] Northouse, P.G. 2016. Leadership. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage Publications, Inc. [ Links ]

[8] Barker, R.A. 2001. The nature of leadership. Human Relations, 54(4), pp. 469-494. [ Links ]

[9] Crevani, L., Lindgren, M. and Packendorff, J. 2007. Shared leadership: A postheroic perspective on leadership as a collective construction. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(1), pp. 40-67. [ Links ]

[10] Rost, J.C. 1991. Leadership for the twenty-first century. New York, USA: Praeger. [ Links ]

[11] Clarke, N. 2012. Shared leadership in projects: A matter of substance over style. Team Performance Management, 18(3/4), pp. 196-209. [ Links ]

[12] Kocolowski, M.D. 2010. Shared leadership: Is it time for a change? Emerging Leadership Journeys, 3(1), pp. 22-32. [ Links ]

[13] Stentz, J.E., Plano Clark, V.L. and Matkin, G.S. 2012. Applying mixed methods to leadership research: A review of current practices. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(6), pp. 1173-1183. [ Links ]

[14] Mosley, A.L. 1998. Organizational studies approach to leadership: Implications for diversity in today's organizations. The Journal of Leadership Studies, 5(1), pp. 38-50. [ Links ]

[15] House, R.J. 1975. Path-goal theory of leadership. [ Links ]

[16] Avolio, B.J., Walumbwa, F.O. and Weber, T.J. 2009. Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), pp. 421-449. [ Links ]

[17] Dinh, J.E., Lord, R.G,. Garnder, W.L., Meuser, J.D., Liden R.C. and Hu, J. 2014. Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: Current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(1), pp. 36-62. [ Links ]

[18] Müller, R., Packendorff, J. and Sankaran, S. 2017. Balanced leadership: A new perspective for leadership in organizational project management, in Cambridge handbook of organizational project management, 1st ed., Sankaran, S., Müller, R. and Drouin, N. (eds), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

[19] Milosevic, I. and Bass, A.E. 2014. Revisiting Weber's charismatic leadership: Learning from the past and looking to the future. Journal of Management History, 20(2), pp. 224-240. [ Links ]

[20] Pearce, C.L. and Wassenaar, C.L. 2014. Leadership is like fine wine: It is meant to be shared, globally. Organizational Dynamics, 43(1), pp. 9-16. [ Links ]

[21] Zhu, J., Liao, Z., Yam, K.C. and Johnson, R.E. 2018. Shared leadership: A state-of-the-art review and future research agenda. Journal of Organizational Behavior, in press. [ Links ]

[22] Ensley, M.D., Hmieleski, K.M. and Pearce, C.L. 2006. The importance of vertical and shared leadership within new venture top management teams: Implications for the performance of startups. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(3), pp. 217-231. [ Links ]

[23] Author. 2017.

[24] Barker, R.A. 1997. How can we train leaders if we do not know what leadership is? Human Relations, 50(4), pp. 343-362. [ Links ]

[25] Knox, D., Ellis, M., Speering, R., Asvadurov, S., Brinded, T. and Brow, T. 2017. The art of project leadership: Delivering the world's largest projects. McKinsey Insights. [ Links ]

[26] Lindgren M. and Packendorff, J. 2009. Project leadership revisited: Towards distributed leadership perspectives in project research. International Journal of Project Organization and Management, 1(3), pp. 285-308. [ Links ]

[27] Hoch, J., Pearce, C.L. and Welzel, L. 2010. Is the most effective team leadership shared? The impact of shared leadership, age diversity, and coordination on team performance. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9(3), pp. 105-116. [ Links ]

[28] Day, D.V., Gronn, P. and Salas, E. 2004. Leadership capacity in teams. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), pp. 857-880. [ Links ]

[29] Houghton, J.D., Neck, C.P. and Manz, C.C. 2003. Self-leadership and super-leadership: The heart and art of creating shared leadership in teams, in Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Pearce, J.A. and Conger, C.L. (eds), Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 123-135. [ Links ]

[30] Müller, R. 2017. Personal communication. [ Links ]

[31] Ding, X., Li, Q., Zhang, H., Sheng, Z. and Wang, Z. 2017. Linking transformational leadership and work outcomes in temporary organizations: A social identity approach. International Journal of Project Management, 35, pp. 543-556. [ Links ]

[32] Jaskyte, K. 2004. Transformational leadership, organizational culture, and innovativeness in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 15(2), pp. 153-168. [ Links ]

[33] Carson, J.B., Tesluk, P.E. and Marrone, J.A. 2007. Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. The Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), pp. 1217-1234. [ Links ]

[34] D'Innocenzo, L., Mathieu, L.E. and Kukenberger, M.R. 2016. A meta-analysis of different forms of shared leadership-team performance relations. Journal of Management, 42(7), pp. 1964-1991. [ Links ]

[35] Hoch, J.E. and Dulebohn, J.H. 2013. Shared leadership in enterprise resource planning and human resource management system implementation. Human Resource Management Review, 23(1), pp. 114-125. [ Links ]

[36] Wood, M.S. 2005. Determinants of shared leadership in management teams. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 1(1), pp. 64-85. [ Links ]

[37] Cox, J.F., Pearce, C.L. and Perry, M.L. 2003. Toward a model of shared leadership and distributed influence in the innovation process, in Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Pearce, J.A. and Conger, C.L. (eds), Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 48-76. [ Links ]

[38] Burke, C.S., Fiore, S.M. and Salas, E. 2003. The role of shared cognition in enabling shared leadership and team adaptability, in Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Pearce, J.A. and Conger, C.L. (eds), Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 103-122. [ Links ]

[39] Agarwal, U.A., Dixit, V., Jain, K., Sankaran, S., Nikolova N., Müller, R. and Drouin, N. 2017. Exploring vertical and horizontal leadership in projects: A comparison of Indian and Australian contexts, in Accelerating development: Harnessing the power of project management. India: PMI. [ Links ]

[40] Locke, E.A. 2003. Leadership: Starting at the top, in Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Pearce, J.A. and Conger, C.L. (eds), Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 271 -284. [ Links ]

[41] Conger, J.A. and Pearce, C.L. 2003. A landscape of opportunities, in Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership. Pearce, J.A. and Conger, C.L. (eds), Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 285-303. [ Links ]

[42] Müller, R., Zhu, F., Sun, X., Wang, L. and Yu, M. 2017. The identification of temporary horizontal leaders in projects: The case of China. International Journal of Project Management, in press. [ Links ]

[43] Pearce, C.L., Wassenaar, C.L. and Manz, C.C. 2014. Is shared leadership the key to responsible leadership? The Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(3), pp. 275-288. [ Links ]

[44] Hsu, J.S., Li, Y. and Sun, H. 2017. Exploring the interaction between vertical and shared leadership in information systems development projects. International Journal of Project Management, 35(8), pp. 15571572. [ Links ]

[45] Zander, L. and Butler, C.L. 2010. Leadership modes: Success strategies for multicultural teams. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 26(3), pp. 258-267. [ Links ]

[46] Pearce, C.L. 2004. The future of leadership: Combining vertical and shared leadership to transform knowledge work. Academy of Management Executive, 18(1), pp. 47-57. [ Links ]

[47] Fausing, M.S., Joensson, T.S., Lewandowski, J. and Bligh, M. 2015. Antecedents of shared leadership: Empowering leadership and interdependence. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 36(3), pp. 271 -291. [ Links ]

[48] Serban, A. and Roberts, A.J.B. 2016. Exploring antecedents and outcomes of shared leadership in a creative context: A mixed-methods approach. The Leadership Quarterly, 27, pp. 181 -199. [ Links ]

[49] Müller, R., Sankaran, S., Drouin, N., Niklova, N. and Vagaasar, A.L. 2015. The socio-cognitive space for linking horizontal and vertical leadership, in APROS/EGOS Conference, pp. 1 -8. [ Links ]

[50] Jiang, J., Klein, G. and Chenoun-Gee, H. 2001. The relative influence of IS project implementation policies and project leadership in eventual outcomes. Project Management Journal, 32(3), pp. 49-55. [ Links ]

Available online 9 Nov 2018

* Corresponding author: Suzaan.pretorius@up.ac.za

# The author was enrolled for a PhD (Project Management) in the Department of Engineering and Technology Management, University of Pretoria, South Africa