Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

On-line version ISSN 2224-7890

Print version ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.27 n.3 Pretoria Nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7166/27-3-1635

GENERAL ARTICLES

Exploring the link between PPM implementation and company success in achieving strategic goals: an empirical framework

C. OosthuizenI, *, #; S.S. GrobbelaarII; W. BamI

IDepartment of Industrial Engineering, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

IIDepartment of Industrial Engineering, Stellenbosch University and DST-NRF CoE in Scientometrics and Science, Technology and Innovation Policy, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Organisations are constantly under pressure to innovate and grow by successfully executing their business strategies. The ever-increasing rate of change in technology has implications for product lifecycles, cost pressures, expectations of higher quality, and a larger variety of products and services. These trends result in mounting pressures and a huge increase in complexity, as the drivers of technology must be managed to achieve a competitive advantage. Project portfolio management (PPM) is a solution for unravelling the complexities of multi-projects. In theory, PPM assists an organisation to achieve this competitive advantage through implementing its business strategy, balancing its portfolios, maximising value, and ensuring resource adequacy. There is, however, a lack of empirical evidence on the use and success of PPM approaches in South Africa. This article presents a framework that lays the foundation of an empirical study that will aim to explore the link between PPM implementation and company success in achieving strategic objectives. We base our framework on the factors of good practice in PPM, which include 1) single-project-level characteristics and activities; 2) multi-project-level characteristics and activities; 3) the link between projects and strategy process; and 4) availability and quality of project information.

OPSOMMING

Maatskappye is alewig onder druk om te innoveer en groei deur die besigheid se strategie suksesvol uit te voer. Met die konstante veranderinge in tegnologie is daar implikasies vir die maatskappy in die vorm van produkte se lewensiklusse, koste, verwagtinge van hoër kwaliteit, en groter verskeidenheid produkte en dienste. Die tendense veroorsaak druk en 'n styging van kompleksiteit om 'n kompeterende voordeel te behaal. Portefeulje projekbestuur is 'n oplossing om die kompleksiteit van multi-projekte te ontrafel en om 'n maatskappy te help om die besigheidstrategie te implementeer, die portefeulje te balanseer, maksimum waarde te behaal, as ook seker te maak daar is genoeg hulpbronne. Daar is 'n tekort aan empiriese werk oor die gebruik en sukses van portefeulje projek bestuur in Suid Afrika. Hierdie artikel ontwikkel 'n raamwerk wat as fondasie dien vir 'n empiriese studie deur die verhouding, tussen portefeulje projekbestuurimplementering en maatskappy sukses faktore te ondersoek. Die basis van die raamwerk sal die volgende faktore van goeie praktyk bevat: 1) enkelprojek-vlak eienskappe en -aktiwiteite; 2) multi-projek-vlak eienskappe en -aktiwiteite; 3) verband tussen projekte en die strategieproses; 4) beskikbaarheid en kwaliteit van projek -informasie.

1 INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM STATEMENT

Firms continually face difficulties with implementing strategies, rather than with formulating them [1]; [2]. In 1998 Grundy [3] stated that the implementation phase is frequently the graveyard of strategy, and remains a neglected area in research. More recent literature has agreed with this statement [4]; [5]. It has been suggested that the solution could lie in making use of project portfolio management (PPM) e.g. [5]; [6]; [7].

Although PPM has been well-researched ([8]; [9]; [10]; [11]; [12]; [13]; [14]), there is still a lack of empirical evidence in the literature on achieving success through implementing PPM factors of best practice, especially in the South African environment ([5]; [7]; [4]). This article aims to lay the groundwork for a study that will address the lack of empirical evidence on PPM in the South African context by deductively constructing a framework from the literature. This article constructs a framework on previous PPM research to broaden the understanding of the relationship between best PPM practices and achieving PPM success. This article defines PPM and its objectives, discusses some of the challenges faced in PPM, gives an overview of practices including tools, models, and two example frameworks, highlights factors of good practice in PPM, and concludes with a framework for further empirical studies.

2 METHODOLOGY

This article develops a framework for an empirical study that will explore the link between PPM-related factors and practices and achieving PPM success. To achieve this, we use a qualitative methodology similar to that proposed by Jabareen [15] to develop a conceptual framework. Jabareen [15] proposed a process of eight phases to develop and evaluate the conceptual framework. These phases form the basis for the framework development process followed in this study, as shown in Table 2, which summarises the objectives, actions taken, and location of each phase in this article. Figure 1 also provides a visual representation of the process.

3 PROJECT PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT PRACTICES

Executing phases 1, 2, and 3 provided the basis for the outputs obtained in the following phases, which are presented in this section. Phase 4 (highlighted in Figure 2) aimed to deconstruct and categorise concepts by identifying concept attributes, assumptions, characteristics, and role [15]. From this process of deconstruction and categorisation, three important themes were identified: the objectives of PPM; the challenges often faced in executing PPM; and the approaches to assessing PPM. Each of these is discussed in more detail in sections 3.1 to 3.3.

There has been a shift in the PPM literature, with Spradlin and Kutoloski [16] and Dawidson [17] stating that portfolio management extends beyond evaluation techniques towards a more complete managerial approach; that it not only focuses on techniques, tools, and methods, but also includes aspects of how PPM is practiced. Consequently, the multifaceted goals and benefits of portfolios must be established before the selection of any projects can take place to meet the organisation's overall objectives [1]. Corporate strategy is typically operationalised on a business level, filtered down to the portfolio level, and finally taken to the project level [8]. This makes it necessary to strengthen the links between these levels for effective and efficient work to be done.

Coordinating the management of projects and portfolios benefits the organisation [18]. Some of the literature is dedicated to highlighting the importance of portfolio management in evaluating, prioritising, and selecting projects in line with the organisation's strategy (e.g. [19]; [20]; [21]; [22]). PPM is growing in importance for organisations competing in a global dynamic environment where organisational survival depends on a steady stream of successful new products [23]. Effectively implementing organisational strategy through a portfolio of projects, and in so doing enhancing the long-term value of the portfolio, are the primary goals of PPM [24].

3.1 PPM objectives

Cooper et al. ([19], [25], and [26]) summarised the objectives of PPM, which are well-established in the literature. They are:

1. Value maximisation - some firms focus on allocating resources and maximising the value of the portfolio in terms of the company's objectives. These objectives include return-on investment, long-term profitability, the likelihood of success, or some other strategic objectives.

2. Balance - the right balance must be achieved through the use of some parameters: the balance between long-term and short-term projects; high-risk projects versus low-risk projects; and the balancing of technologies, markets, project types, and product categories.

3. Strategic direction - the final portfolio of projects must truly reflect the business's strategy and the breakdown of spending across markets, areas, projects, and other categories that are directly tied to the organisation's strategy.

4. The right number of projects - the three objectives mentioned above all have superimposed resource constraints; but this objective attempts to quantify the project's demand for resources (usually 'people', expressed as 'person-days' of work) versus the readiness of the required resources.

3.2 PPM challenges

Using PPM practices offers many benefits, such as managing projects, allocating resources, scheduling, analysing, and governance of the projects and business [27]. However, companies also face challenges when using PPM. A literature review highlighted six major problem areas that organisations face when managing multi-projects or making use of PPM practices (refer to Table 2). Due to the portfolio being handled as a whole, the challenges are not independent of one another. For example, inadequate information challenges cause challenges in other areas, such as not choosing the right projects on the portfolio-level activities. It is worth noting that the challenges are linked to the success factors of PPM, which will be discussed further in Section 3.4.

3.3 Assessing the portfolio

Some researchers ([11], [8], [19], and [21]) claim that the project portfolio selection is important, and have thus explored the necessary tools, techniques, and frameworks; but the clear and formal prioritisation process is often not enough for the optimal success of a portfolio.

3.3.1 PPM tools

Selecting techniques and tools is helpful to evaluate quantitative and qualitative indicators for individual projects or a group of projects. These techniques and tools are grouped into methods or, as Cooper et al. [9] call them, 'goals'. The literature contains many discussions and debates on the methods and tools used for the selection of a project portfolio. Taylor [28] discusses the fundamental six characteristics any model should have, regardless of the nature of the model (numeric or nonnumeric), as follows: flexibility, realism, ease of use, capability, cost-effectiveness, and ease of computerisation. Meredith and Mantel [29] propose criteria for choosing a selection model, and suggest that the required information be categorised under the following headings: (1) production; (2) marketing; (3) financial; (4) personnel; and (5) administrative and miscellaneous factors.

Cooper et al. [19] discuss the popularity of the techniques, tools, models, and methods for project selection and PPM. Their results mainly show three things: first, organisations tend to use a combination of techniques, tools, and methods; second, financial methods are the most popular, but do not necessarily produce the best-performing portfolios; and third, the organisations with the best performance portfolios rely more on strategic approaches rather than on financial methods. Despite the variety in techniques, tools, and approaches, it is important to pay close and continuous attention to the project interactions, such as the competition for resources and the time-dependent nature of the projects [30].

3.3.2 PPM frameworks

The literature reveals that more than one hundred techniques and tools support an organisation in selecting projects for its portfolio [31]; [8]; [32]. Each tool has its own advantages and disadvantages, making it necessary for organisations to apply a variety of tools and techniques ([19]; [8]). This requires organisations to adapt or develop a logical framework or process through which the necessary tools and techniques are integrated and selected to support the organisation's project portfolio selection. To be effective in project portfolio management, an appropriate framework must be chosen to evaluate project proposals and select a project portfolio that is best aligned with the corporate strategy [10].

3.3.3 Framework of Archer and Ghasemzadeh [10]

As with the Stage-Gate process that Cooper et al. [33] use, Archer and Ghasemzadeh [10] also propose prequalification of each project before moving on to the next step or stage of the selection process. This eliminates bad proposals by narrowing the choice down to necessary projects. Archer and Ghasemzadeh [10] developed a framework, widely used and referred to in the literature, that is a logical series of activities requiring full involvement by the selection committee. The framework has three phases:

1. Strategic considerations: These help to determine the strategic focus and overall budget allocation for the portfolio; to consider the external (market) environment and the internal (strengths and weaknesses) environment; and to develop a strategy.

2. Individual project evaluation: The projects are measured individually, evaluating the benefits, and valuing each project that contributes to the portfolio.

3. Portfolio selection: This phase deals with the selection of portfolios built on candidate project parameters; this includes the interactions of projects and resource constraints and independencies.

4 BEST PRACTICE MECHANISMS

Phase 5 (highlighted in Figure 3) defined two specific aspects of PMM: (1) the success factors, otherwise referred to as the 'best practices' of PPM (to avoid confusion with success criteria); and (2) the success criteria of PPM. The success factors (or best practices) are considered in Section 4.1, while the success criteria are considered in Section 4.2.

4.1 Success factors / best practices

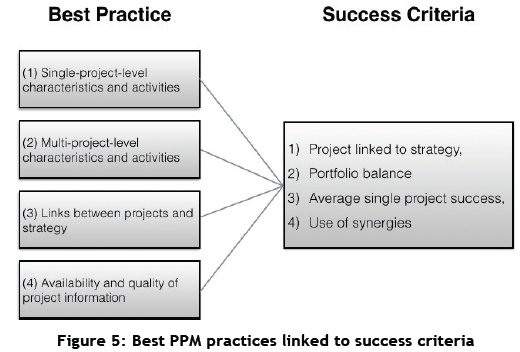

The best practices of PPM are divided into four categories that were adopted from a study done by Dietrich and Lehtonen [5]: 1) single-project-level characteristics and activities; 2) multi-project-level characteristics and activities; 3) links between projects and strategy process; and 4) availability and quality of project information. These are considered in Sections 4.1.1 to 4.1.4, while Section 4.1.5 provides a summary of the factors and a structuring of these factors into a framework structure.

4.1.1 Single-project-level characteristics and activities

Some strategy-based PPM practices suggest that portfolio-level decisions should be made at a single-project level or through a development process ([8]; [19]; [25]; [26]; [34]; and [18]). Martinsuo and Lehtonen [35] found in their study of a variety of industries that single-project management is linked with PPM efficiency; their quantitative study shows that single-project factors such as goal-setting, decision-making, and information-availability are related to PPM efficiency. Meshendahl [1] proposes that one of the key elements in project portfolio success is single-project success. The triangle of virtue (time, cost, and quality) was generally an agreed foundation for the definition of project success in early research [36].

Elonen and Artto [37] state that their study's results indicated inadequate definition, management of single projects, and planning; the problems in this area mostly suggest inadequacy in the pre-project phase and in project monitoring and control. Martinsuo and Lehtonen's [35] findings also stressed the importance of single-project management, yet how inadequately it is connected to PPM efficiency. They stated that companies should pay more attention to the way in which they go about building links between single-project management capabilities and PPM efficiency practices.

4.1.2 Multi-project-level characteristics and activities

The literature acknowledges that it is not ideal for single projects to be isolated entities, but should rather be treated in the complex context that is set by the programmes or project portfolios of which the project is a part [7]. Some authors have called the multi-project setting "project portfolio management" ([35]; [8]; [25]; [10]; and [18]). Platje et al. [18] state that more benefits can be delivered from managing all the projects within a portfolio than from managing individual projects independently. Elonen and Artto [37] found in their study that the most frequently mentioned problem in portfolio level activities is the overlapping of tasks and projects. They concluded that this could be a result of the same work being done a few times in one or several different projects; the objectives of all projects not being systematically incorporated into the strategy; and/or the projects not being prioritised due to the lack of methods for prioritisation.

Although the complexities of managing a portfolio can be daunting, proper management and practices can decrease work and risk, and improve synergies such as resources, knowledge, marketing, and technologies [38]. To assess PPM and its effects, the results have to be assessable and cover a broader perspective than individual projects [35]; [5]. A variety of different measures, tools, and models are used, but a widely-agreed approach to project portfolio success is to focus on the objectives suggested by Cooper et al. [26]. Killen and Hunt's study proved that strategic methods could result in a better alignment of projects with the business strategy, and that portfolio mapping methods result in a better balancing of a portfolio. Other popular methods are the scoring methods that are used to rank projects. There is an assortment of techniques and tools for the optimum selection of projects and portfolios. The literature suggests a contingency view by fitting the portfolio selection approach to the organisation's specific characteristics and strategy [39]; [7].

4.1.3 Link between projects and strategy process

One of the major objectives and challenges in a portfolio is the link between projects and strategy [25]. The PPM literature encourages selecting and prioritising projects based on the organisation's strategy [35]. To complement the goals of single projects, PPM aims to do the right projects that create a link from the projects to the strategy, simultaneously achieving long-term success [37]. According to Shenhar et al. [40], defining and assessing project success is an important strategic management concept that helps to align the project efforts with the short- and long-term goals of the organisation. Rapid change and global competition force organisations to be quick to respond and to be more competitive. Shenhar et al. [40] state that projects must be perceived as strategic weapons, created for competitive advantage and economic value; project managers must assume the role of strategic leaders who take responsibility for project business results. No longer will projects be just operational tools that execute strategy; rather, they will be the driving force for new strategic directions.

A common characteristic or objective in a variety of approaches is to increase the manageability and coordination over multi-projects, resulting in better links between projects and strategic aims [5]. Martinsuo and Lehtonen [35] found a positive indirect relationship between clearly-specified goals (scope, costs, and time) and PPM efficiency, through PM efficiency and reaching individual project goals. The literature suggests that the portfolio selection approach must be fitted to the surrounding organisation's specific characteristics and strategy [39]; [21]. To prove this, Müller et al. [7] found a positive correlation between the selection of projects for the portfolio, based on the organisation's strategy. Also, portfolio management-driven organisations are more advanced in decision-making practices than less mature multi-project organisations. Killen et al. [23] showed that the use of a strategic method could result in the better alignment of projects with the business strategy. Organisations that successfully manage strategic alignment in multi-project environments analyse the objectives of ongoing projects and the links to strategic formulation [5].

4.1.4 Availability and quality of project information

Martinsuo and Lehtonen [35], who focused on single-project factors, found that the availability of information on projects was shown to be the most significant factor (for decision-makers) that contributed to PPM efficiency, directly and through PM efficiency. Müller et al. (2008), who focused on multi-projects, also found a positive correlation between projects, programme reporting, and portfolio performance. Information has an impact not only on the portfolio manager, but on everyone in the portfolio management process.

The project portfolio provides an organisation with a snapshot of its current strategic direction, making it important for portfolio managers, portfolio teams, organisational executives, and other stakeholders to have accurate information about the portfolio's status. Relevant information is necessary to make informed decisions; by addressing the information problem, other portfolio management questions can be addressed [27]. Archer and Ghasemzadeh [8] state that the internal competencies and external environmental data should be considered carefully before strategic decisions about the project portfolio are made; data should be relevant and accessible. The firm's ability to generate information systematically for competitive advantage is known as the 'analytical posture' [41]. This posture considers systematic environmental analysis, for example, of market developments, technology development, new technologies, and strategic competence [1].

Frequently, however, there is a lack of transparency and information flow. Personnel can suffer from information overload; or they are not always told what information to use, to whom it must go, how, and in what format [37].

4.1.5 Summary of portfolio success factors

Portfolio success factors are critical factors that are required to achieve the desired success of a portfolio. Although the factors alone are not responsible for success or failure, addressing the factors would add to the success of the portfolio [41]. Dietrich and Lehtonen [5] identified four categories of portfolio success factors: (1) single-project-level characteristics and activities; (2) multi-project-level characteristics and activities; (3) links between projects and strategy process; and (4) availability and quality of project information.

The table below shows how some authors have contributed to the planning and development of the success factors for the conceptual framework. (More detail on contributions to the design of the conceptual framework is found in Table 4.)

4.2 Project portfolio management success

Success is defined differently across industries; the contexts of projects vary, and so does the definition of success [40]. Many studies have shown that, to have a sustainable view of success, financial criteria alone are insufficient [43]. The following table determines the most common success criteria in the PPM literature.

As seen in the table above, the top six success criteria found in the literature are the following, in ranking order: projects linked to strategy, portfolio balance, average single project success, use of synergies, maximising value, and preparing for the future. Meskendahl [1] states that the first objective (maximising value) of Cooper et al. [26] can be divided into two independent dimensions: (1) average single-project success (time, quality, budget, and customer satisfaction), and (2) the use of synergies between projects. Using Meskendahl's logic could narrow the success criteria to three; but how the success should be measured depends on the choice, project, and interpretation of the researcher or practitioner. In this article, the following will be taken as success criteria:

(1) Project linked to strategy,

(2) Portfolio balance,

(3) Average single project success, and

(4) Use of synergies.

The criterion of average single-project success is linked to the success factor category of single-project-level activities and characteristics, and is thus important in this study. Although using synergies criteria is equally used to value maximisation, it is easier to measure the value maximisation through financial methods because it is less dependent on the type of project.

5 TOWARDS AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

Phase 6 (highlighted in Figure 4) aimed to construct a conceptual framework. In this study, this was achieved by integrating the result of the previous phase to create a conceptual framework that could form the basis for an empirical study to investigate the causal links between various PPM best practices towards PPM success. This linking of the two concepts investigated in the previous section is indicated in Figure 5.

6 CONCLUSION

From a thorough literature review, it was concluded that there is a lack of empirical evidence on the employment and success of PPM practices and approaches in South Africa. To address this gap, this article lays a foundation for an empirical study to explore the link between PPM implementation and company success in achieving the strategic objectives of PPM. Through a literature investigation, a framework was constructed on four categories of best PPM practice. The factors include: 1) single-project-level characteristics and activities; 2) multi-project-level characteristics and activities; 3) links between projects and strategy process; and 4) availability and quality of project information. Similarly, the success criteria by which these best practices should be measured were identified to be 'project linked to strategy', 'portfolio balance', 'average single-project success', and 'maximising value'. These two categories of concepts provide a point of departure for a much-needed future empirical study that will identify the causal links towards PPM success in the South African context.

7 RECOMMENDATION

This study has laid a foundation for an empirical study to be done on the four factors and key sub-factors. We recommend taking this study further by doing an empirical investigation of the correlation between the factors and the portfolio's success. The factors can be assessed against the four project portfolio success criteria individually, to make it more convenient for organisations and researchers to see what factors could benefit each specific success criterion. Sending out the framework to managers who work with project portfolio management could provide results. Validation (such as using interviews) could be used to justify or contradict the findings of the empirical study. Other sub-factors could be investigated and built on through thorough research.

REFERENCES

[1] Meskendahl, S. 2010. The influence of business strategy on project portfolio management and its success: A conceptual framework, International Journal of Project Management, 28(8), pp. 807-817. [ Links ]

[2] Hrebiniak, L.G. 2006. Obstacles to effective strategy implementation, Organizational Dynamics, 35(1), pp. 12-31. [ Links ]

[3] Grundy, T. 1998. Strategy implementation and project management, International Journal of Project Management, 16(1), pp. 43-50 [ Links ]

[4] Buys, A.J. and Stander, M.J. 2011. Linking projects to business strategy through project portfolio management, The South African Journal of Industrial Engineering. [ Links ]

[5] Dietrich, P. and Lehtonen, P. 2005. Successful management of strategic intentions through multiple projects: Reflections from empirical study, International Journal of Project Management, 23(5), pp. 386391. [ Links ]

[6] Grundy, T. 2000. Strategic project management and strategic behaviour, International Journal of Project Management, 18(2), pp. 93-103. [ Links ]

[7] Müller, R., Martinsuo, M. and Blomquist, T. 2008. Project portfolio control and portfolio management performance in different contexts, Project Management Journal, 39(3), pp. 28-42. [ Links ]

[8] Archer, N.P. and Ghasemzadeh, F. 1999. An integrated framework for project portfolio selection, International Journal of Project Management, 17(4), pp. 207-216. [ Links ]

[9] Cooper, R.G., Edgett, S.J. and Kleinschmidt, E.J. 1997. Portfolio management in new product development: Lessons from the leaders, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 15(2), pp. 186-187 [ Links ]

[10] Pennypacker, J.S. and Dye, L.D. (2002) Managing multiple projects: Planning, scheduling, and allocating resources for competitive advantage, Vol. 5. Edited by James S. Pennypacker. New York: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

[11] Cooper, R.G., Edgett, S.J. and Kleinschmidt, E.J. 1992. New product portfolio management: Practices and performance, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 16(4), pp. 333-351. [ Links ]

[12] Artto and Dietrich (2004) 'Strategic Business Management Through Multiple Projects', in The Wiley Guide to Project, Program & Portfolio Management. Chapter 1, pp. 1-33. [ Links ]

[13] Kaiser, M.G., El Arbi, F. and Ahlemann, F. 2015. Successful project portfolio management beyond project selection techniques: Understanding the role of structural alignment, International Journal of Project Management, 33(1), pp. 126-139. [ Links ]

[14] Loch, C.H. and Kavadias, S. 2002. Dynamic portfolio selection of NPD programs using marginal returns, Management Science, 48(10), pp. 1227-1241. [ Links ]

[15] Jabareen, Y. (2009) 'Building a Conceptual Framework: Philosophy, Definitions, and Procedure', International Journal of Qualitative Methods, pp. 49-62. [ Links ]

[16] Spradlin, C.T. and Kutoloski, D.M. (1999) 'Action-Oriented Portfolio Management', Research Technology Management, 42(2), pp. 26-32. [ Links ]

[17] Dawidson, O. (2006) Project Portfolio Management - an organising perspective. [ Links ]

[18] Platje, A., Seidel, H. and Wadman, S. (1994) 'Project and Portfolio Planning Cycle', International Journal of Project Management, pp. 100-106. [ Links ]

[19] Cooper, R., Edgett, S. and Kleinschmidt, E. 2001. Portfolio management for new product development: Results of an industry practices study, R and D Management, 31(4), pp. 361-380. [ Links ]

[20] Blichfeldt, B.S. and Eskerod, P. 2008. Project portfolio management: There's more to it than what management enacts, International Journal of Project Management, 26(4), pp. 357-365. [ Links ]

[21] Englund, R.L. and Graham, R.J. 1999. From experience: Linking projects to strategy, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 16(1), pp. 52-64. [ Links ]

[22] Archer, N.P. and Ghasemzadeh, F. (1996) 'Project Portfolio Selection Techniques: A review and Suggested Integrated Approach', Innovation Research Working Group WORKING PAPER, NO. 46 [ Links ]

[23] Killen, C.P. and Kleinschmidt, E.J. 2008. Project portfolio management for product innovation, International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 25(1), pp. 24-38. [ Links ]

[24] Killen, C.P. (2015) 'Chapter 1: Organizational Agility Through Project Portfolio Management', Portfolio Management: A Strategic Approach, pp. 1-14. [ Links ]

[25] Cooper, R.G., Edgett, S.J. and Kleinschmidt, E.J. (1999) 'New product portfolio management: Practices and performance', Journal of Product Innovation Management, 16(4), pp. 333-351. [ Links ]

[26] Cooper, R.G., Edgett, S.J. and Kleinschmidt, E.J. (2002) 'Portfolio management: fundamental to new product success', Product Development Institute. [ Links ]

[27] Joslin, R. (2015) 'Addressing portfolio information issues through the use of business social networks, stars, and gatekeepers', in Levin, G. and Wyzalek., J. (eds.) Portfolio management: a strategic approach. [ Links ]

[28] Taylor, J. 2006. A survival guide for project managers. 2nd ed. New York: American Management Association. [ Links ]

[29] Meredith and Mantel (2009) [ Links ]

[30] António, A. and Madalena, A. 2009. Project portfolio management phases: A technique for strategy alignment, International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering. [ Links ]

[31] Dos Santos, B.L. (1989) 'Selecting information systems projects: problems, solutions and challenges', Hawaii Conference on System Sciences, p. pp. 1131±1140. [ Links ]

[32] Ghasemzadeh, F. and Archer, N.P. 2000. Project portfolio selection through decision support, Decision Support Systems, 29(1), pp. 73-88. [ Links ]

[33] Cooper, Edgett and Kleinschmidt (2000) 'New Problems, New Solutions: Making Portfolio Management More Effective', Research Technology Management, Industrial Research Institute, pp. 18-33. [ Links ]

[34] Stamelos, I. and Angelis, L. 2001. Managing uncertainty in project portfolio cost estimation, Information and Software Technology, 43(13), pp. 759-768. [ Links ]

[35] Martinsuo, M. and Lehtonen, P. 2007. Role of single-project management in achieving portfolio management efficiency, International Journal of Project Management, 25(1), pp. 56-65. [ Links ]

[36] Westerveld, E. 2003. The project excellence model®: Linking success criteria and critical success factors, International Journal of Project Management, 21(6), pp. 411-418. [ Links ]

[37] Elonen, S. and Artto, K.A. 2003. Problems in managing internal development projects in multi-project environments, International Journal of Project Management, 21(6), pp. 395-402. [ Links ]

[38] Loch, C.H. and Kavadias, S. 2002. Dynamic portfolio selection of NPD programs using marginal returns, Management Science, 48(10), pp. 1227-1241. [ Links ]

[39] Stawicki, J. and Müller, R. 2007. From standards to execution: Implementing program and portfolio management, Poland IPMA World Congress. [ Links ]

[40] Shenhar, A.J., Dvir, D., Levy, O. and Maltz, A.C. 2001. Project success: A multidimensional strategic concept, Long Range Planning, 34(6), pp. 699-725. [ Links ]

[41] Morgan, R.E. and Strong, C.A. (2003) 'Business performance and dimensions of strategic orientation', Journal of Business Research, 56(3), pp. 163-176 [ Links ]

[42] Marnewick, C. 2015. Portfolio management success, in Levin, G. and Wyzalek, J. (eds), Portfolio management: A strategic approach [ Links ]

[43] Voss, M. 2012. Impact of customer integration on project portfolio management and its success: Developing a conceptual framework, International Journal of Project Management, 30(5), pp. 567-581. [ Links ]

[44] Martinsuo, M., Korhonen, T. and Laine, T. 2014. Identifying, framing and managing uncertainties in project portfolios, International Journal of Project Management, 32(5), pp. 732-746 [ Links ]

[45] Kendall, G. (2003) Advanced project portfolio management and the PMO. Edited by S Rollins. Florida: J. Ross Publishing; 2003. [ Links ]

[46] Teller, J. and Kock, A. 2013. An empirical investigation on how portfolio risk management influences project portfolio success, International Journal of Project Management, 31(6), pp. 817-829. [ Links ]

[47] Beringer, C., Jonas, D. and Georg Gemünden, H. 2012. Establishing project portfolio management: An exploratory analysis of the influence of internal stakeholders' interactions, Project Management Journal, 43(6), pp. 16-32. [ Links ]

[48] Kopmann, J., Kock, A., Killen, C. and Gemuenden, H. (2014) 'Business Case Control: The Key to Project Portfolio Success or Merely a Matter of Form?', European Academy of Management, EURAM, 4-7 June, Valencia. [ Links ]

[49] Stettina, C.J. and Hörz, J. 2015. Agile portfolio management: An empirical perspective on the practice in use, International Journal of Project Management, 33(1), pp. 140-152. [ Links ]

[50] Kock, A., Heising, W. and Gemünden, H.G. 2016. A contingency approach on the impact of front-end success on project portfolio success, Project Management Journal, 47(2), pp. 115-129 [ Links ]

Available online 11 Nov 2016

Presented at the 27 annual conference of the Southern African Institute for Industrial Engineering (SAIIE), held from 27-29 October 2016 at Stonehenge in Africa, North West, South Africa.

* Corresponding author chiaraoosthuizen@gmail.com

# The author was enrolled for an M Eng (Industrial) degree in the Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Stellenbosch