Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

On-line version ISSN 2224-7890

Print version ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.27 n.3 Pretoria Nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7166/27-3-1625

GENERAL ARTICLES

Developing design propositions for an open innovation approach for SMEs

Department of Industrial Engineering University of Stellenbosch, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This paper proposes design propositions for an open innovation approach for small and medium-sized enterprises based on the open innovation lifecycle framework. The design propositions direct small- and medium-sized enterprises in implementing, executing, and improving open innovation in their organisations. The design propositions are developed through a synthesis of the literature on open innovation and other implementation and improvement best practices.

A design sciences method is followed, using context interaction mechanism outcome logic to conduct a systematic review of the literature on open innovation, and using the open innovation lifecycle framework as boundaries. Twenty-two design propositions are formulated as a result. A case study is also discussed as an initial test of the application of the design propositions.

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel stel ontwerp proposisies voor vir 'n oop innovasie benadering vir klein en middelslag ondernemings, gebaseer op die oop innovasie lewensiklus raamwerk. Die ontwerp proposisies stuur klein en middelslag besighede in die implementering, uitvoering, en verbetering van oop innovasie in hul organisasies. Die ontwerp proposisies is ontwikkel deur die verwerking van die literatuur oor oop innovasie en ander implementering en verbetering beste praktyke.

'n Ontwerp wetenskap metode is gevolg, met die gebruik van konteks interaksie meganisme uitkoms logika om 'n sistematiese hersiening van die literatuur op oop innovasie te doen met die gebruik van die open innovasie lewensiklus raamwerk as perke. Hierdeur is 22 ontwerp proposisies formuleer. 'n Gevallestudie word ook bespreek as 'n aanvanklike toets van die toepassing van die ontwerp proposisies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Open innovation provides an approach that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can use to gain access to knowledge and technology from outside of their own organisations, and to benefit from selling or leasing their own intellectual property to other organisations. Open innovation differs from 'closed innovation' in that it opens the boundaries of the organisation to in- and out-flows of innovation knowledge and technologies, instead of innovating in an exclusively closed environment within the organisation. Open innovation can include various methods such as customer co-creation, eliciting ideas for new products from suppliers or customers, incorporating intellectual property through patents from other industries into your own innovation, or allowing other companies to take your patents to market if not aligned to your own business strategy. As a still-emerging management practice, open innovation within SMEs still requires research-driven outputs that can guide SMEs on how to adopt open innovation in their organisations.

SMEs play a vital role in the economy of countries around the world, and are vital for the development of new products and services. Managing the development of an innovation in the market is an important function for any organisation. In SMEs, this is often done more through trial and error than through a structured and managed approach.

This paper proposes design propositions for an open innovation approach for SMEs. The design propositions direct SMEs in the implementation, execution, and improvement of open innovation in their organisations. The design propositions are based on a synthesis of the literature on open innovation and other implementation and improvement best practices. One illustrative scenario is also discussed.

2 METHODOLOGY

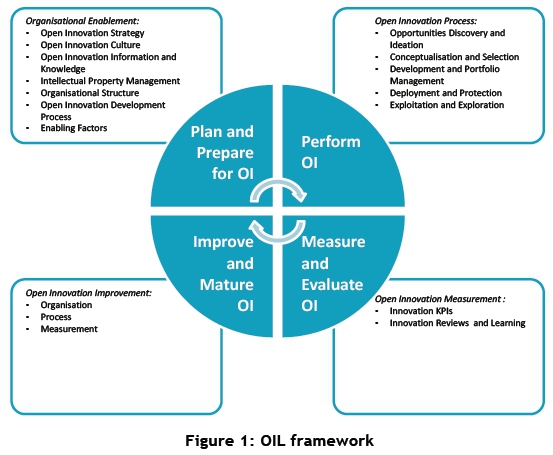

To focus the systematic review of literature and research synthesis, the author made use of the open innovation lifecycle (OIL) framework [1] to guide the process. By using the OIL framework (Figure 1), boundaries for the review are set and act as an initial step to a systematic review of the parameters or question to be answered [2, 3, 4].

The OIL framework is based on models and frameworks from the literature, and was developed as a precursor to the development of an open innovation (OI) approach for SMEs. "The four main components of the framework are: Plan and Prepare for OI, Perform OI, Measure and Evaluate OI, and Improve and Mature OI" [1]. The OIL framework follows an iterative cycle similar to the 'plan do check act' (PDCA) cycle [5] that allows the process to be improved, rather than being a once-off exercise. The OIL framework was designed using design requirements (including user requirements, functional requirements, design restrictions, attention points, and boundary conditions) developed by Krause and Schutte [6]. The design requirements were derived from a survey of South African SMEs to obtain a view of their current use and perception of open innovation [6]. The survey identified a strong need for the development of an open innovation approach for SMEs.

During the systematic review process, the author sought to answer the question, "What information, patterns, trends, and learning can be obtained from the literature, framed by the OIL framework, that would assist with developing design propositions for open innovation in SMEs?".

A design sciences approach is followed to develop the design propositions in this paper. "Design Science refers to an explicitly organised, rational and wholly systematic approach to design" [7]. "Design Science Research in management aims both to develop knowledge to design interventions to solve improvement problems and to design systems (coherent structures and processes) to solve construction problems" [8]. It follows the "process of abstracting: generalising from the inputs from the prior research work" [9].

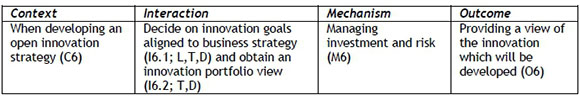

Further to the design sciences approach, the context interaction mechanism outcome (CIMO)-logic concept will be used to structure the design propositions. CIMO-logic can be used in the form of one-liners, tables, articles, reports, guidance notes, or even books [10, 11, 12]. To facilitate ease of use, the author chose to capture the design propositions in a table format.

The table shows the relationships between context, intervention, mechanism, and outcome. These relationships are not necessarily one-to-one relationships, and can include many-to-one and one-to-many relationships [8, 9, 11, 12]. A single outcome can therefore be achieved through multiple interactions and mechanisms within a single context, for example.

Considering the high-level research problem, and following the example of Weber [12], the overarching design proposition is described below. The CIMO-logic within the design proposition is coded using the CIMO acronym and a number.

3 DEVELOPING THE DESIGN PROPOSITIONS

The design proposition (Table 1) shows the relationships at the highest level of abstraction, and comprises one-to-one relationships. Flowing from this highest level context is the framed context within the OIL framework. The four main components in the framework are:

• Plan and prepare for open innovation

• Perform open innovation

• Measure and evaluate open innovation

• Improve and mature open innovation

These four main components will form another level of 'context' for the design requirements. Within the main components, the OIL framework also suggests core elements to be considered when performing open innovation. These core elements therefore become the 'interactions' to be considered. Using the OIL framework components thus forms the basis for developing the design propositions during the systematic review and synthesis.

3.1 Innovation maturity

Innovation maturity refers to how developed an organisation is in its innovation management and execution. The literature on open innovation maturity for SMEs and for larger organisations is, however, sparse.

Flynn and Wang [14] propose an open innovation model as adapted from Chesbrough. Brunswicker and Van de Vrande [15] and Brunswicker and Ehrenmann [16] describe a case using open innovation maturity in a technology SME [15, 16]. Enkel et al. [17] also suggest an open innovation framework, albeit focused on large organisations; and MacKinven et al. [18] provide a three-level maturity model for external searching open innovation. Forrester [19] proposes four stages of open innovation maturity, also from a large organisation perspective.

It is clear from the literature that there is no agreed maturity framework for open innovation in SMEs. The author therefore decided to use a maturity scale appropriate to the study, based on the scarce literature on this topic. For this study, three levels of maturity will be used to describe the depth and breadth of open innovation within an organisation. The innovation maturity levels used for this study are described as follows:

Limited - Open innovation is a transactional, once-off event without deep partnerships being built. Organisational enabling factors are limited, and open innovation is not the dominant innovation method in the organisation. Open innovation projects are sporadic and reactive, rather than planned and deliberate.

Transitional - Open innovation is becoming more prevalent and deeper partnerships, and wider networks are being established. Open innovation projects are much more strategic and are tied to the organisation's strategy. Most organisational enablement factors are established, and innovation performance is measured as input for continuous improvement of the open innovation capability.

Developed - Open innovation is the dominant innovation method in the organisation, with an established process being followed. The organisation is actively looking for opportunities to engage in open innovation, aligned to their organisational and innovation strategies. Trusted partnerships and innovation networks have been built. All organisational enablement factors are purposefully optimised.

Maturity in terms of design propositions using the CIMO-logic can be viewed as a context type. The innovation maturity gives context to the organisational environment in which the interactions need to take place.

Within this study, we added the acronyms L (limited), T (transitional), and D (developed) to the interactions to indicate maturity context where applicable. This should be seen as an indication of the most applicable maturity context within which the interactions can be applied, but should not be considered as a definitive rule. As with all design propositions, the maturity context serves as guideline to users who still need to make decisions that are most appropriate to their organisational context and constraints.

3.2 Design propositions summary

Using the OIL framework components, and examining the literature associated with each component topic as input into further possible design propositions, a literature synthesis was conducted, resulting in the development of 22 design propositions to be used for the implementation, execution, and improvement of open innovation in SMEs. More than 60 references in the literature were used to develop the design propositions (see Table 3). The process of synthesis, discussion, and proposition development formed part of a larger research piece that, because of space limitations, cannot be fully discussed in this paper. Each design proposition, however, is underpinned by a detailed motivation and discussion of the literature that supports it. The summarised design propositions provided in Table 2 thus form an end result of the design requirements and framework pre-cursers developed towards the open innovation approach [1; 34] and a thorough synthesis of the literature. The 22 design propositions developed through this process are listed below.

4 DISCUSSION

The design propositions developed in Section 3 provide an open innovation approach for SMEs to follow, regardless of their open innovation maturity level. The approach is flexible enough to cater for various contexts that the SME might face, without limiting its application. A balance is sought between prescription and own judgement.

The design propositions are captured in an open innovation lifecycle framework that aims to improve the process of innovation continuously within the organisation, and to make it a more predictable and repeatable process. Each design proposition guides the user through suggestions to consider throughout the open innovation lifecycle, with options obtained from the literature on innovation and business management methods, thus formalising efforts that are often ad hoc in nature in many SMEs [6].

The first five design propositions provide boundaries within which to apply the subsequent design propositions, in line with the open innovation lifecycle framework. Design propositions six to 14 focus on setting up the organisation for open innovation. They address issues such as strategy alignment, organisational structure, culture, intellectual property management, and open innovation method selection. They prepare the organisation to begin the innovation process.

Design propositions 15 to 19 describe the steps within the innovation process. They take the user through the five steps, starting with new idea discovery for an innovation, and ending with ways to extract the most value from the innovation after launching it in the market. Not all of the steps would necessarily be followed, such as when an idea is developed only to the concept phase, but is then sold to an outside organisation in the form of a patent to take to market. The next two design propositions (20 and 21) guide the organisation in measuring and evaluating its open innovation performance. Appropriate KPIs can be selected and measured, providing input into a process of evaluation and learning.

This then leads to the last design proposition, which creates options for improvement and a selection process to carry options into the next cycle of open innovation application.

As an example of how to use a design proposition, we'll look at design proposition six, and describe a possible scenario.

In this phase, the SME would look at how to set up the organisation for open innovation and, following the design proposition, develop an open innovation strategy. The first part of the Interaction - deciding on innovation goals - is suggested for organisations at all levels of maturity, whereas developing an innovation portfolio view is only recommended for organisations at a transitional or developed level of maturity. This does not mean that organisations at a limited level of maturity cannot also consider this step; but it would normally be more difficult for them, due to factors such as the size of the organisation, the structures and processes in place, and the number of innovation projects they can manage at any given time. The theoretical review used to derive the propositions provides insight into how to perform these tasks in more detail. SMEs would further consider their own risk appetite and the finances available to them to invest in innovation, resulting in a view of which innovation will be developed in the organisation aligned to their business strategy.

Working through the design propositions therefore gives SMEs a structured approach when applying open innovation in their organisations. It is not necessarily a strictly linear process; the user can apply discretion and judgment either to skip certain propositions if they are not applicable to their situation, or to iterate through them multiple times if required.

5 USER TEMPLATES

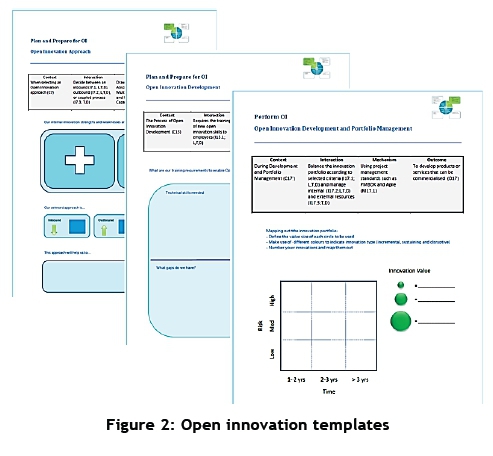

To make the design propositions more accessible and user-friendly, the authors developed templates that can be used by the SME during the process of applying the design propositions in their organisation. Simplifying theory into a template (or canvas) - taking academic concepts and turning them into practical tools for use - has gained a lot of support since 2010. Examples of this trend can be seen in the work of Osterwalder [78] and the popular business model canvas, or the canvasses available from the open innovation agency 100%Open [79].

Following a similar approach, the authors developed templates for the design propositions for the SME to use as part of their open innovation toolkit. Figure 2 shows an example of the templates created for the toolkit. The templates therefore supplement the design propositions and aim to make it easier for SMEs to apply in their organisations.

Eighteen templates were developed to cover the key questions that the SME should ask during the use of the open innovation approach. They allow for an easier way to engage with the content and to facilitate discussion between team members in the organisation. The template shows which quadrant in the OIL framework the user is in, provides the applicable design proposition in CIMO-logic format, and then poses questions to be completed by the SME that will address the specific section of the approach. This can, for example, be to define the open innovation method chosen, or perhaps to choose the preferred partners with whom to engage.

6 ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

As a first step to evaluating the design propositions and templates in a real-world scenario, a session was held with an SME to test the utility and practicality of the artefacts. The design propositions (including the supporting theoretical detail on which the propositions were based) and the templates were provided to the SME for review before the session. The session was conducted via Skype.

The SME owner was taken through the concept of the design propositions and the templates, explaining how to use them and apply them in an organisation. Two templates were also run through in detail to illustrate their use. The owner was then given a chance to provide feedback and ask questions on the content. She then also provided formal feedback, using a questionnaire that rated the utility and applicability of the propositions and templates, using a Likert scale and general comments. The questionnaire consisted of 24 questions that tested various elements of the design propositions and the templates.

6.1 SME profile

The SME is a knowledge capital consultancy focusing on identifying, leveraging, and measuring the value of knowledge assets in small- to medium-sized businesses in South Africa. The company has three employees, and has been in business for three-and-a-half years.

6.2 Feedback summary

The feedback provided was very positive overall, with none of the questions being rated in the negative part of the scale.

The approach was considered to support repeated and continued use, with the SME owner stating:

"This is an approach that an SME can become comfortable and familiar with and use as a strategic tool".

A strong aspect of the approach was considered to be that it is generic and flexible enough to be used by SMEs in different industries and at different levels of maturity and capability.

Feedback received about the templates was that they serve the following purposes:

• They pull the approach together into a practical application

• They allay the fear of where to start - what are my first next steps?

• Being transparent and practical, they encourage the SME to use the framework

The SME owner also provided some suggestions for improvement:

"I feel that the approach is comprehensive, but I am reticent to agree that an SME will be able to implement this on their own the first time - especially if they are new to the whole concept of open innovation. Suggest compiling a glossary of terms for quick reference for the newly initiated into the open innovation space. Perhaps a suggestion for the future is a dashboard template that gives the user a high level overview of their particular information."

Closing comments were very encouraging in supporting the usability of the approach through the following statements:

"This approach is particularly refreshing as it seeks to extend the relationship capital of an SME, inviting clients, partners, and vendors etc. to participate in the innovation process and creating additional value for the knowledge assets of the organisation. This plays into the business model of the SME and can provide an entirely new income stream for the organisation. I feel that this approach opens up new avenues for SMEs who are on various levels to participate, experiment and grow their business while still having to deliver business as usual. This is a very exciting piece of work - as an SME, it offers a practical way to participate in Open Innovation".

7 CONCLUSION

This paper described the development of design propositions for an open innovation approach for SMEs, building on prior work in the form of the open innovation lifecycle framework. A design sciences method was followed, using CIMO-logic to conduct a systematic review of the literature on open innovation, using the OIL framework as boundaries, and resulting in the formulation of 22 design propositions.

In addition to the design propositions, the authors also developed templates based on the design propositions that SMEs can apply practically when implementing and applying the design propositions within their organisations. The templates aim to make the approach more accessible to users of different skill levels, thus increasing their utility.

An initial case where the approach was tested was very positive, with only minor recommendations being made to improve its usefulness to SMEs. Overall, it was well received, and considered to be very useful for SMEs to adopt. Further cases should be done to support this initial test.

The combination of framework, design propositions, and templates now forms an approach that can be used by SMEs in implementing, executing, and improving open innovation in their organisations.

REFERENCES

[1] Krause, W. & Schutte, C.S.L. 2015. A framework towards an open innovation approach for SMEs. Conference Proceedings, International Association for Management of Technology IAMOT 2015, Cape Town, South Africa. [ Links ]

[2] Biolchini, J., Mian, P.G. & Natali, A. 2005. Systematic review in software engineering. Systems Engineering and Computer Science Department, COPPE / UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

[3] Khan, K.S., Kunz R., Kleijnen, J. & Antes, G. 2003. Five steps to conducting a systematic review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96, pp 118-121. [ Links ]

[4] Booth, A., Papaioannou, D. & Sutton, A. 2012. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. SAGE. [ Links ]

[5] Moen, R. & Norman, C. 2010. Circling back: Clearing up the myths about the Deming cycle and seeing how it keeps evolving. Qual Progress, 42, 23-8. [ Links ]

[6] Krause, W. & Schutte, C.S.L. 2015. A perspective on open innovation in South African small and medium sized enterprises and design requirements for an open innovation approach. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 26(1), pp 163-178. [ Links ]

[7] Cross, N. 2001. Designerly ways of knowing: Design discipline versus design science. Design Issues, 17(3), pp 49-55. [ Links ]

[8] Denyer, D., Tranfield, D. & Van Aken, J.E. 2008. Developing design propositions through research synthesis. Organization Studies, 29, pp 393-413. [ Links ]

[9] Tan, W.L. 2010. SMEs and international partner search. Doctoral dissertation, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven. [ Links ]

[10] Van Aken, J.E. 2013. Design science: Valid knowledge for socio-technical system design. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 388, pp 1-13. [ Links ]

[11] Van Staveren, M.T. 2009. Design propositions for implementing risk management in organizations. Doctoral dissertation, University of Twente, Groningen, The Netherlands. [ Links ]

[12] Weber, M. 2011. Customer co-creation in innovations: A protocol for innovating with end users. Doctoral thesis, Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. [ Links ]

[13] Piller, F. & West, J. 2014. Firms, users, and innovation: An interactive model of coupled open innovation. In New frontiers in open innovation, Henry Chesbrough, Wim Vanhaverbeke and Joel West (eds), Oxford: Oxford University Press, Chapter 2. [ Links ]

[14] Flynn, M. & Wang, C. 2012. A framework for open innovation. SAP Community Network. [ Links ]

[15] Brunswicker, S. & Van de Vrande, V. 2014. Exploring open innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. In New frontiers in open innovation, Henry Chesbrough, Wim Vanhaverbeke and Joel West (eds), Oxford: Oxford University Press, Chapter 7. [ Links ]

[16] Brunswicker, S. & Ehrenmann, F. 2013. Managing open innovation in SMEs: A good practice example of a German software firm. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management (IJIEM), 4(1), 2013, pp 33 - 41. [ Links ]

[17] Enkel, E., Bell J. & Hogenkamp H. 2011. Open innovation maturity framework. International Journal of Innovation Management, 15(6), pp 1161-1189. [ Links ]

[18] MacKinven, S., MacBryde, J. & Wagner, B. 2014. Sensing opportunities: Is there a need for a managed search process in open innovation? Conference Proceedings, 21st EurOMA Conference. Palermo, Italy, 2014, pp 1-10. [ Links ]

[19] Mattes, F. 2012. Moving from open innovation to true open innovation. InnovationManagement.SE online at http://www.innovationmanagement.se/2012/10/08/moving-from-open-innovation-to-true-open-innovation/. [ Links ]

[20] Golightly, J., Ford, C., Sureka, P. & Reid, B. 2012. Realising the value of open innovation. The Big Innovation Centre, The Work Foundation and Lancaster University. [ Links ]

[21] Igartua, J.I., Garrigós, J.A. & Hervas-Oliver, J.L. 2010. How innovation management techniques support an open innovation strategy. Research - Technology Management, May-June, 2010, pp 41-52. [ Links ]

[22] Almquist, E., Leiman, M., Rigby, D. & Roth, A. 2013. Taking the measure of your innovation performance. Bain & Company. [ Links ]

[23] Brunswicker, S. & Vanhaverbeke, W. 2014. Open innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): External knowledge sourcing strategies and internal organizational facilitators. Journal of Small Business Management, (53) 4, pp 1241-1263. [ Links ]

[24] Giannopoulou, E., Yström, A. & Ollila, S. 2011. Turning open innovation into practice: Open innovation research through the lens of managers. International Journal of Innovation Management, 15(3), pp 505-524. [ Links ]

[25] Vanhaverbeke, W. 2013. Rethinking open innovation beyond the innovation funnel. Technology Innovation Management Review, April 2013, pp 6-10. [ Links ]

[26] Vanhaverbeke, W., Vermeersch, I. & De Zutte, S. 2012. Open innovation in SMEs: How can small companies and start-ups benefit from open innovation strategies? Flanders DC Knowledge Centre. [ Links ]

[27] Minderhoud, S. 2012. Balancing the nine power questions of innovation excellence. Conference Proceedings, ISPIM 2012. Barcelona, Spain. [ Links ]

[28] Gassmann, O. & Enkel, E. 2004. Towards a theory of open innovation: Three core process archetypes. Proceedings of the R&D Management Conference. Lisbon, Portugal. [ Links ]

[29] Manceau, D., Moatti, V., Fabbri, J., Kaltenbach, P. & Bagger-Hansen, L. 2011. Open innovation - What is behind the buzzword? ESCP Europe & Accenture. [ Links ]

[30] Mattes, F. 2011. How to make open innovation work for your R&D. Applied Innovation Management, #3, InnovationManagement.SE. [ Links ]

[31] Gay, B. 2014. Open innovation, networking, and business model dynamics: The two sides. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 3(2), pp 1-20. [ Links ]

[32] Boudreau, K.J. & Lakhani, K.R. 2009. How to manage outside innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review, 50(4), pp 68-76. [ Links ]

[33] Cohen, W.M. & Levinthal, D.A. 1990. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), pp 128-152. [ Links ]

[34] Chesbrough, H. & Brunswicker, S. 2013. Managing open innovation in large firms. Fraunhofer Verlag. [ Links ]

[35] OPINET 2011. Open innovation: Benefits for SMEs. European Collaborative and Open Regional Innovation Strategies - EURIS Program. [ Links ]

[36] Brunswicker, S. 2011. An empirical multivariate examination of the performance impact of open and collaborative innovation strategies. Doctoral dissertation, Institut für Arbeitswissenschaft und Technologiemanagement der Universität Stuttgart, Germany. [ Links ]

[37] Vahter, P., Love, J.H. & Roper, S. 2012. Openness and innovation performance: Are small firms different? Working Paper No. 113. Warwick Business School, University of Warwick. [ Links ]

[38] Lee, S., Park, G., Yoon, B. & Park, J. 2010. Open innovation in SMEs: An intermediated network model. Research Policy, 39(2010), pp 290-300. [ Links ]

[39] Van de Vrande, V., De Jong, J.P.J., Vanhaverbeke, W. & De Rochemont, M. 2008. Open innovation in SMEs: Trends, motives and management challenge. Scientific Analysis of Entrepreneurship and SMEs (SCALES). [ Links ]

[40] Mortara, L., Napp, J.J., Slacik, I. & Minshall, T. 2009. How to implement open innovation: Lessons from studying large multinational companies. University of Cambridge. [ Links ]

[41] West, J. & Bogers, M. 2014. Leveraging external sources of innovation: A review of research on open innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(4), pp 814-831. [ Links ]

[42] Wagner, P. & Piller, F. 2012. Are you ready for open innovation processes? Performance, 4(2), pp 22-31. [ Links ]

[43] Spitzley, A. & Schweinfort, W. 2007. Better and faster - Innovation as success story, in Open Innovation for small and medium sized enterprises, Anne Spitzley et al. (eds), Fraunhofer-Institute for Industrial Engineering. [ Links ]

[44] De Jong, M., Marston, N., Roth, E. & Van Biljon, P. 2013. The eight essentials of innovation performance. McKinsey & Company. [ Links ]

[45] Lichtenthaler, U. & Lichtenthaler, E. 2009. A capability-based framework for open innovation: Complementing absorptive capacity. Journal of Management Studies, 46 (8), pp 1315-1338. [ Links ]

[46] Bianchi M., Cavaliere, A., Chiaroni, D., Frattini, F. & Chiesa, V. (2011). Organisational modes for open innovation in the bio-pharmaceutical industry: An exploratory analysis. Technovation, 31, pp 22-33. [ Links ]

[47] Karlsson, M. 2010. Collaborative idea management: Using the creativity of crowds to drive innovation. Applied Innovation Management, #1, InnovationManagement.SE. [ Links ]

[48] Brunswicker, S. 2009. The networked SME: Taking a closer look into open and collaborative innovation in European SMEs. Open Innovation Speaker Series, Haas School of Business, UC Berkeley. [ Links ]

[49] CEIN, VDC & INNONET 2012. Practical guide for SMEs on the management of legal issues related to open innovation. European Collaborative and Open Regional Innovation Strategies - EURIS Program. [ Links ]

[50] Alexy, O., Criscuolo, P. & Salter, A. 2009. Does IP strategy have to cripple open innovation? MIT Sloan Management Review, 51(1), pp 71-77. [ Links ]

[51] Mehlman, S.K., Uribe-Saucedo, S., Taylor, R.P., Slowinski, G., Carreras, E. & Arena, A. 2010. Better practices for managing intellectual assets in collaborations. Research-Technology Management, 53(1), pp 55-66. [ Links ]

[52] Chiaroni, D., Chiesa, V. & Frattini, F. 2011. The open innovation journey: How firms dynamically implement the emerging innovation management paradigm. Technovation, 31, pp 34-43. [ Links ]

[53] Kirchgeorg, V., Achtert, M. & Großeschmidt, H. 2010. Pathways to innovation excellence: Results of a global study by Arthur D. Little. Arthur D. Little. [ Links ]

[54] Ebert, J., Chandra, S. & Liedtke, A. 2008. Innovation management strategies for success and leadership. A.T. Kearney, Inc. [ Links ]

[55] Project Management Institute. 2013. Managing change in an organisation: A practice guide. Available online from http://www.pmi.org/learning/change-management.aspx. [ Links ]

[56] OPINET. 2011. Open innovation: Open innovation best practice guide. European Collaborative and Open Regional Innovation Strategies - EURIS Program. [ Links ]

[57] Huizingh, E.K.R.E. 2011. Open innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. Technovation, 31, pp 2-9. [ Links ]

[58] Du Preez, N.D. & Louw, L. 2008. A framework for managing the innovation process. Conference Proceedings, PICMET '08. [ Links ]

[59] Slowinski, G. & Sagal, M.W. 2010. Good practices in open innovation. Research-Technology Management, 53(5), pp 38-45. [ Links ]

[60] Gassmann, O. & Enkel, E. 2004. Towards a theory of open innovation: Three core process archetypes. Proceedings of the R & D Management Conference. Lisbon, Portugal. [ Links ]

[61] Phillips, J. 2011. Open innovation technology. In A guide to open innovation and crowd sourcing: Advice from leading experts, Paul Sloane (ed.), London: Kogan Page Limited, Chapter 3. [ Links ]

[62] Ries, E. 2011. The lean startup: How constant innovation creates radically successful businesses. Portfolio Penguin. [ Links ]

[63] Fetterhoff, T.J. & Voelkel, D. 2006. Managing open innovation in biotechnology. Research-Technology Management, 49(3), pp 14-18. [ Links ]

[64] O'Sheedy, D. & Sankaran, S. 2013. Agile project management for IT Projects in SMEs: A framework and success factors. The International Technology Management Review, 3(3), pp 187-195. [ Links ]

[65] Baruah, N. & Ashima. 2012. A survey of the use of agile methodologies in different Indian small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs). International Journal of Computer Applications, 47(20), pp 38-44. [ Links ]

[66] Project Management Institute. 2008. A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK Guide), Fourth Edition. PMI, Inc, Pennsylvania, USA. [ Links ]

[67] Chesbrough, H. & Bogers, M. 2014. Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In New frontiers in open innovation, Henry Chesbrough, Wim Vanhaverbeke and Joel West (eds), Oxford: Oxford University Press, Chapter 4. [ Links ]

[68] Bianchi, M., Campodall'Orto, S., Frattini, F. & Vercesi, P. 2010. Enabling open innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: How to find alternative applications for your technologies. R&D Management, 40 (4), pp 414-431. [ Links ]

[69] Arrigo, E. 2012. Alliances, open innovation and outside-in management. SYMPHONYA Emerging Issues in Management, 2, pp 53-65. [ Links ]

[70] MED. 2012. Hidden innovation initiatives for SMEs. BIC, MED and European Union Development Fund. [ Links ]

[71] Erkens, M., Wosch, S., Piller, F. & Lüttgens, D. 2014. Measuring open innovation: A toolkit for successful innovation teams. Performance, 6 (2), pp 12-23. [ Links ]

[72] Adams, R., Bessant, J. & Phelps, R. 2006. Innovation management measurement: A review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8(1), pp 21-47. [ Links ]

[73] Nada, N. 2010. A framework for systematic application and measurement of the innovation management process. The Journal of Knowledge Economy & Knowledge Management, V (Fall), pp 57-69. [ Links ]

[74] Garibaldo, F., Hauß, I. & Mendibil, J. 2007. A reference model for excellence in innovation management. In Open innovation for small and medium sized enterprises, Anne Spitzley et al. (eds), Fraunhofer-Institute for Industrial Engineering. [ Links ]

[75] Nonaka, I., Konno, N. & Toyama, R. 2001. Emergence of 'BA'. In Knowledge emergence: Social, technical, and evolutionary dimensions of knowledge creation, Ikujirö Nonaka and Toshihiro Nishiguchi (eds), Oxford University Press, pp 13-29. [ Links ]

[76] Schutte, C.S.L. & Du Preez, N. 2010. A comparative study about the formal design life cycle of the integrated knowledge network to support innovation. Conference Proceedings, International Conference on Competitive Manufacturing - COMA 2010, Stellenbosch, South Africa. [ Links ]

[77] DTI. 2015. Tools & techniques for process improvement. Department of Trade and Industry, UK. Available online: www.dti.gov.uk/quality/tools. [ Links ]

[78] The business model canvas. Available online: https://strategyzer.com/canvas [ Links ]

[79] Open Innovation Toolkit. Available online: http://www.toolkit.100open.com/ [ Links ]

Available online 11 Nov 2016

Presented at the 27 annual conference of the Southern African Institute for Industrial Engineering (SAIIE), held from 27-29 October 2016 at Stonehenge in Africa, North West, South Africa.

* Wkrause.au@gmail.com

# Author was enrolled for a PhD in the Department of Industrial Engineering, Stellenbosch University