Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

versión On-line ISSN 2224-7890

versión impresa ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.27 no.3 Pretoria nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7166/27-3-1624

GENERAL ARTICLES

Towards a holistic customer experience management framework for enterprises

L. du PlessisI, II, *, #; M. de VriesI, †

IDepartment of Industrial and Systems Engineering University of Pretoria, South Africa

IIKnotion Consulting (Pty) Ltd

ABSTRACT

We have entered the age of the customer where customer choice is the main differentiator between enterprises. Therefore, enterprises need to shift their focus to customer experience management (CEM). A survey conducted within the telecommunications sector indicated a gap between theoretical CEM approaches and their implementation in enterprises. Although a systematic literature review and inductive thematic analysis of CEM literature revealed nine common themes, none of the existing approaches includes all of these themes in a comprehensive way. Based on those nine themes, this paper presents a new holistic framework for CEM that managers and practitioners concerned with improving customer experiences could use.

OPSOMMING

Dit is die era van die kliënt - waar kliënte keuse die hoof differensieerder vir ondernemings geword het. Ondernemings moet nou hulle fokus skuif na kliënte-ervaringsbestuur. 'n Studie gedoen in die telekommunikasie sektor het 'n gaping gevind tussen huidige teoretiese benaderings en hoe hulle prakties geïmplementeer word deur maatskappye. 'n Sistematiese literatuurstudie en induktiewe tematiese analise van kliënte-ervaringsbestuur literatuur het nege gemene temas opgelewer. Dit is ook gevind dat geen van die benaderings holisties al nege temas bevat nie. Die artikel stel 'n nuwe benadering voor - 'n holistiese raamwerk vir kliënte-ervaringsbestuur wat deur bestuurders en praktisyne gebruik kan word vir die verbetering van kliënte-ervarings.

1 INTRODUCTION

As customers' expectations for choice between products, services, and preferred channels increase, customer service excellence becomes increasingly important to all enterprises that deliver a product or a service to their customers. The service-profit chain [1, 2] is one of the earliest concepts that addresses the importance of quality customer service and its cause-and-effect relationships with other variables in the enterprise. The service-profit chain establishes relationships between profitability, the customer, and the employee.

Forrester Research [3] argues that since 2010 we have entered the Age of the Customer; manufacturing strength, distribution power, and information mastery have started to dissolve as competitive boundaries, and have largely become commoditised. According to Manning and Bodine [3], customer choice is becoming the main differentiator, and enterprises need to shift their focus to customer experience management (CEM).

The customer experience challenge is one faced by all services companies, including those in telecommunications. As these companies face increased competition and declining average revenue per user (ARPU) [4], they also have to focus on customer experience improvement to differentiate their services from their competitors. A global survey conducted by the Tele-management Forum, which sampled 18 telecommunications service providers, indicated that the majority of them (especially those in emerging countries such as South Africa) identified CEM as an important strategic focus area [5].

However, implementing a capability for good CEM in an enterprise and improving the customer experience continuously are not simple matters. Many factors influence the customer's experience and inevitably affect customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction. The service-profit chain [1,2] mentions service value, employee loyalty, productivity and satisfaction, as well as internal service quality, as factors that influence the customer experience. According to Meyer and Schwager [6] , customer experience does not improve until it becomes a top priority and until a company's work processes, systems, and structure change to reflect this customer-centric priority. Rae [7] agrees that companies are starting to focus on the importance of customer experience and the complex mix of strategy, integration of technology, orchestrating business models, brand management, and executive commitment.

A survey was conducted to assess the maturity of CEM in telecommunication companies in South Africa and the use of existing CEM approaches and tools, as well as their perceived success/usability [8]. The survey questions were based on a study by Forrester [9], in which the maturity and practices of 86 customer experience professionals from global companies were assessed. The survey was sent to various employees in large telecommunication companies in South Africa, and 32 responses were obtained. The detailed survey discussion and the results are discussed in Du Plessis [8]. The key findings from the survey results indicated that:

• Many telecommunications providers are focused on CEM as a strategic initiative, and have dedicated, centralised CEM teams. However, CEM efforts are still distributed across the enterprise, and are not coordinated in a single, holistic approach.

• The biggest obstacles to CEM implementation were: (1) Operational priorities override importance; (2) The enterprise culture is not conducive to customer-centricity; (3) A lack of understanding of customer experience and CEM; and (4) A knowledge gap about how to operationalise customer experience and channel the results to the business to drive change.

Based on the results of the preliminary survey, it can be argued that there is a gap between current theoretical CEM approaches and their practical implementation in South African telecommunication enterprises. A research question that needs to be investigated is whether a comprehensive CEM approach that includes existing CEM tools and techniques in a holistic way could enhance their value, and lead to improved customer experiences within a telecommunication enterprise. In searching for a comprehensive CEM approach, this paper presents the results of a systematic review of the existing CEM literature, followed by an inductive thematic analysis to extract nine common themes from the existing CEM approaches. Since the thematic analysis of the existing literature indicates that none of the existing theoretical approaches includes the nine themes in a comprehensive way, it is suggested that a holistic CEM framework is developed. The main contribution of this paper is the development of a comprehensive CEM framework, based on the nine themes identified in the literature. Implementation of the framework should ultimately lead to improved customer experiences and higher profits for the enterprise.

The structure of this article is as follows: Section 2 presents the research approach that was followed and the data-gathering instruments that were used to elicit nine common themes from the existing CEM literature. Section 3 presents the results of the systematic literature review to define key concepts within CEM. Section 4 presents the quantitative results of the inductive thematic analysis of existing CEM models and frameworks, from which nine prominent CEM themes were derived. Section 5 presents the CEM framework, including a short discussion of the framework components. Section 6 concludes with recommendations for future work.

2 RESEARCH METHOD

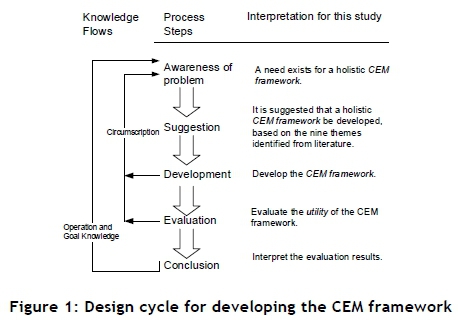

Since the main objective of this study was to design an artefact in the form of a holistic CEM framework, a design science research approach from Vaichnavi and Keuchler [10] was adopted. This approach consists of five process steps. Figure 1 provides an overview of the design cycle and its interpretation for this study in terms of the process steps.

With reference to Figure 1, the first step in the design cycle is the preliminary awareness step, where a preliminary survey was conducted and documented in Du Plessis [8] to confirm and identify the need for a holistic framework for CEM. A systematic literature review was conducted as a scoping review to provide a summary of the topics relating to customer experience, and as a prelude to refining the research. Thereafter, in order to identify themes for CEM inductively from the literature, the systematic review was refined to a more evidence-based review, with an inductive thematic analysis, which verified the theoretical gap for a comprehensive CEM approach.

The main steps and guidelines used for carrying out a systematic review of Hidalgo et al. [11] are discussed next.

1. Define the search terms. According to Colicchia and Strozzi [12], a systematic review can start with search terms, and not necessarily with a particular research question as originally required, especially where the review is conducted for scoping purposes. Thus the following key words were identified for the initial review: customer experience, CEM, customer service quality, perceived quality, customer satisfaction, and quality improvement.

2. Identify the databases, search engines, and journals that may need to be searched manually, and query them with the chosen search terms. Since the study aimed to create an academically-sound yet practical framework for CEM, sources from both academia and practice needed to be used. Academic platforms searched included EbscoHost, Emerald Full Text, IEEE Xplore, SAGE, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink. These were supplemented with material acquired via Google Scholar searches and citations and references from other work or scholars. The material was also supplemented with input from practice through personal contacts, from citations and references from practitioners, and from management books and websites.

3. Decide on and apply filters for inclusion and exclusion. For the initial scoping review, no filters were applied other than the subject/keyword filters. All abstracts were reviewed for relevance in terms of two criteria: (a) Does the material define customer experience or CEM? or (b) Does the material provide a context for customer experience regarding aspects that impact perceived experience or service quality? For the second round, which comprised the inductive thematic analysis, the search was refined to include material from CEM models and frameworks for identifying common themes. Guidelines from Guest et al. [13] were used during the inductive thematic analysis. The number of citations was used as an indication of article quality.

4. Ensure that the resulting articles are representative, by repeating the filtering process. This study was conducted over the course of two years, and the literature review was updated continually to ensure that the material used included the most recent and relevant literature available.

With reference to Figure 1, the second step in the design cycle is the suggestion step. We suggested the development of a holistic CEM framework, based on the nine themes that were identified during the inductive thematic analysis. Since the CEM framework had to provide methodical guidance for using existing CEM tools and techniques in a holistic way, we followed the method-design guidelines of Offermann et al. [14] during the development step of the design cycle (see Figure 1) - i.e., the development of the CEM framework. Figure 1 also includes an evaluation step and a conclusion, which will form part of future work.

3 LITERATURE REVIEW

This section provides an overview of the existing CEM literature (Section 3.1), defines customer experience (Section 3.2), summarises key factors that influence customer experience (Section 3.3), and defines CEM (Section 3.4).

3.1 Existing CEM literature review

According to Fiegen [15] , a systematic literature review of 30 years should reveal evidence of a maturing research methodology. Thus the literature from 1980 to 2014 was analysed for this study. The timeline in Table 1 provides an indication of the evolution of the literature for the past 30 years, starting with the work on service quality in the 1980s, and highlighting the most prominent works. With the emergence of the service-profit chain [2] and the link between customer service and its impact on profit, marketing, and brand management, professionals became interested in the subject. Pine and Gilmore's [16] article "The Experience Economy" first coined the term 'customer experience', and from there many authors (practitioners and academics alike) have given attention to the topic. This has led to multiple streams of research, with some focusing still on experience measurement or quality measurement, whereas others have focused more on the analysis of dimensions that influence customer experience. Another prominent difference in the literature on customer experience is that some professionals have focused on the customer perspective of the experience, whereas others have focused on the enterprise perspective. Only more recently (from 2008 onwards) has literature on CEM emerged, along with methods, models, and frameworks for implementing CEM in an enterprise.

3.2 Definition of customer experience

Throughout the literature, multiple meanings are associated with the term 'customer experience' [43, 44]. Gentile et al. [27] provide a holistic definition of customer experience: "The customer experience originates from a set of interactions between a customer and a product, a company, or part of its organization, which provoke a reaction. This experience is strictly personal and implies the customer's involvement at different levels (rational, emotional, sensorial, physical, and spiritual)". Meyer and Schwager [6] elaborate that the interaction can either be direct and initiated by the customer, such as an intentional purchase, or the interaction can be indirect, which involves unplanned encounters with the company, such as advertising, news, reviews, or unplanned activities in the course of purchase or service. Verhoef et al. [35] agree with this definition, adding that the experience is holistic in nature and encompasses the total experience of the customer through its search, purchase, consumption, and after-sale phases, and may involve multiple channels. Shaw et al. [38] add that the experience is measured against the customer's expectations across all these moments of contact.

Recently, much simpler definitions have been given by practitioners. For instance, some authors argue that customer experience is how your customers perceive their interactions with your company [46], or that customer experience is a blend of the physical product and/or service and the emotions it evoked before, during, and after engaging with your organisation across any touch point [48]. From a telecoms best-practice perspective, Rich [5] defines customer experience as the result of observations, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings arising from interactions and relationships over an interval of time between a customer and their provider. Customer experience is not based only on a single encounter with the customer, but rather on the entire lifecycle or collective encounters a customer has with the company, including advertising, purchasing, using, service interactions, cancelling the contract, or disposing of a product. Thus the customer experience is touch-point agnostic and time agnostic.

3.3 Summary of customer, enterprise, and service relationships

Based on the literature that was reviewed and presented in Table 1, this section summarises the complexity of the customer-enterprise-service relationship and the key factors that influence customer experience. Figure 2 presents a conceptual model that consolidates the existing literature on the interaction between an enterprise and the customer:

• The overlap of the two parallelograms in the model reflects the customer-enterprise overlap, which indicates that the service experience occurs at the point where the customer and enterprise meet (as in a model from Johnston and Kong [44]).

• The rounded rectangles in Figure 2 represent relevant enterprise capabilities and customer actions (intensions or expectations that have an effect on perceived quality).

• Various constructs on Figure 2 are linked via arrows, indicating causal links between them.

• The 'Moderators' rectangles in Figure 2 represent the factors influencing the service process between the customer and the enterprise.

• Perceived quality or service experience is measured through the four dimensions highlighted in Klaus and Maklan [37]: product experience, outcome focus, moments-of-truth, and peace-of-mind (POMP).

The 'Consumer Moderators' rectangle refers to the factors influencing the consumer's perception, which include the six dimensions of experience highlighted in Schmitt [20] and Gentile et al. [27]. Two additional consumer moderators were added: past experience (t-1) from Verhoef et al. [35] and external influences (e.g., word of mouth advertising) from Johnson and Kong [44]. The consumer moderators influence the customer's service expectation, which in turn impacts on the perceived quality of the experience.

• The 'Macro Economic Moderator' rectangle represents the external factors (not controlled by the enterprise or the consumer) that can influence perceived quality. External factors include the current state of the economy, politics, exchange rates, competitor activities, regulatory activities, and the company's brand [28, 35].

• The 'Enterprise Moderators' rectangle represents the multiple factors impacting service delivery from the enterprise side. The enterprise management team has perceptions of the customer's expectations, and these perceptions are translated into experience quality specifications (including service, product, and network quality, as modelled by Lemke et al. [36]). The service quality specifications are used to design the 'experience', and can include factors such as the channel or service interface, retail atmosphere, price, products, assortment, brand, service personnel, and even the service process as represented by Verhoef et al. [35]. How these enterprise factors are designed (based on the customer's expectations) and delivered (based on the enterprise's capabilities) ultimately affects how the service is experienced.

• The 'Situation Moderators' rectangle represents the factors that will have an impact on the service delivered or experienced, even though it is not directly part of the design of the customer's experience. The 'Situation Moderators' include employee factors such as employee satisfaction and company culture [53] and the type and location of the store [35].

• The Gap Model [17] is also incorporated, indicating five gaps as numbered circles in Figure 2:

1. The gap between management's perception of consumer expectations and the consumer's actual expectations.

2. The gap between management's perception of consumer expectations and how these are translated into service quality specifications (customer experience design).

3. The gap between the designed service quality specifications and its actual delivery by the enterprise.

4. The gap between the service delivered by the enterprise and how this service is advertised or communicated to the customer.

5. The gap between the service that was expected by the customer and the perceived quality.

Figure 2 indicates the complexity and multi-faceted nature of customer experience as a management area. Experiences are impacted by various factors; some are directly under the control of the enterprise, such as the service given, the quality of the product, or even hygiene factors, whose importance is only noticed in their absence. Some factors are not under the control of the enterprise (such as available parking space, word-of-mouth advocacy, critique, competitive behaviour, or other macro-economic factors), and these factors all combine to contribute to perceptions of the experience.

3.4 CEM definitions

CEM represents the discipline, methodology, and/or process used to manage a customer's cross-channel exposure, interaction, and transaction with a company, product, brand, or service comprehensively [20]. It encompasses every aspect of a company's offering; the quality of customer care, but also advertising, packaging, product and service features, ease of use, and reliability [6]. These definitions indicate that CEM is a broad field that attempts deliberately to align the enterprise and various activities in an enterprise ultimately to deliver good customer experiences that satisfy the enterprise's customers.

The preliminary systematic literature review revealed that there are a number of approaches (models and frameworks), practices, and guidelines for implementing CEM, or how to ensure delivery of good customer experiences. The next section presents the results of an inductive thematic analysis of selected approaches.

4 ANALYSIS RESULTS

From the initial literature review, 23 approaches (models and frameworks) from different authors were identified that relate specifically to CEM, from the period between 1993 and the more recent approaches developed in 2014. The approaches were analysed using Guest et al.'s [13] inductive thematic analysis guidelines to derive themes for CEM. In this section, the method and the results of the thematic analysis on CEM approaches are discussed.

4.1 Identifying the themes

The results of the inductive thematic analysis indicated that most of the approaches incorporate elements from two common high level themes, with some covering elements of either one or the other, and some covering elements of both themes. These high level themes are:

• A customer experience implementation or management process.

• Organisational capabilities that support good customer experiences.

Regarding the first main theme, 'the customer experience implementation or management process', most customer experience approaches include a cycle of four phases that could also be classified as four sub-themes: customer understanding, customer experience design, customer experience measurement, and customer experience change implementation.

When analysing the second theme, 'organisational capabilities that support good customer experiences', five sub-themes emerged: strategy, leadership, organisational design, culture, and systems, technology and processes.

In accordance with Guest et al.'s [13] best practices for thematic analysis, a code book was created to define and identify the themes and to ensure consistency in coding. Using these codes, a quantitative analysis followed - discussed next.

4.2 Quantitative analysis results

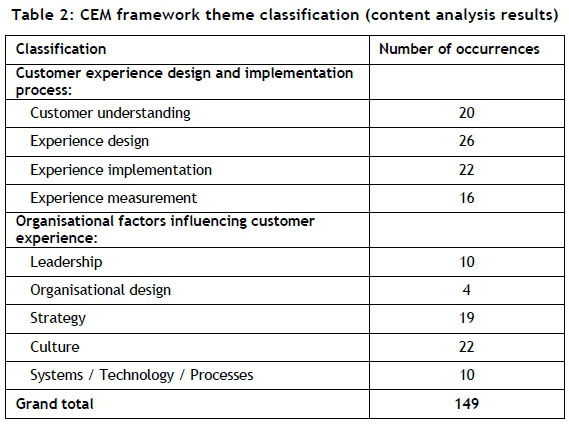

Table 2 provides a summary of the number of occurrences of each theme in the analysed approach content.

The nine identified themes occurred in most of the approaches analysed, although some themes were more prominent than others. The most prominent themes that occurred in most models were experience design, experience change implementation, culture, and customer understanding. Also, it was revealed that none of the analysed approaches or articles covered all nine of the defined themes. Since the thematic analysis was performed in accordance with Guest et al.'s [13] six guidelines, the nine identified themes are representative of the existing CEM approaches, and can be used as a basis for developing a holistic CEM framework. The CEM framework development is presented and discussed in Section 5.

5 THE CEM FRAMEWORK

Using the nine themes identified during the inductive thematic analysis along with Offermann et al.'s [14] method design guidelines, a creative process was followed to construct the CEM framework's components. Section 5.1 provides the context for the CEM framework, and Section 5.2 provides the CEM framework and its components.

5.1 Fra mework context

The objective of the CEM framework is to provide guidance to practitioners on how to align an enterprise to be more customer-centric, and how to implement principles of customer-centricity in an enterprise, which should lead to an enhanced experience for their customers. This section starts with a definition of CEM as a common term of reference, followed by an introduction of the two main components of the CEM framework, its scope and intended audience, prerequisites for its use, and a graphical representation of its components.

5.1.1 Applicable definitions

The CEM framework supports the following definition for CEM: "CEM represents the discipline, methodology and/or process used to comprehensively manage a customer's cross-channel exposure, interaction and transaction with a company, product, brand or service" [20]. Thus CEM is seen as a capability used by enterprises to define, deliver, and manage good customer experiences.

5.1.2 Main components

The CEM method consists of two main parts (derived from the literature in Section 3):

• Part 1: A customer experience design and implementation process. This process is sequential, but is also a continuous improvement process, since the customer's needs and requirements constantly change. These needs must be re-evaluated periodically to ensure that the enterprise is still aligned to deliver on customers' expectations.

• Part 2: Prerequisite building blocks ensure organisational readiness in support of the customer experience process.

5.1.3 Scope and audience

The CEM framework is intended to be applied in all enterprises and all industries. The intended audience of the CEM framework is customer experience officers, marketing segment managers, or other managers in the enterprise who intend to improve the experience of their customers. The CEM framework can also be used by management consultants who assist enterprises to improve customer experiences.

5.1.4 Prerequisites

CEM framework Part 1 prerequisites: Employees who are involved need to have a preliminary understanding of the customer segment for the implementation of CEM Part 1. In the customer experience understanding phase, the research tools that can be used are stipulated. However, since customer research is usually time-consuming, it is suggested that the enterprise has a well-defined customer research team that continually updates the customer research. At the very least, the enterprise needs to be willing to conduct a short survey to obtain a minimum level of understanding of the customer segment and of their requirements and expectations of the enterprise, prior to using this framework.

CEM framework Part 2 prerequisites: The organisational building blocks defined in the CEM framework are stipulated as a prerequisite for organisational readiness in support of the customer experience implementation process (i.e., CEM framework Part 1). Since enterprises differ in size and maturity level in respect of the building blocks, this framework does not require full maturity of all building blocks before the CEM framework is used. However, the CEM framework Part 1 may be less effective if the organisational building blocks are immature.

5.1.5 Graphical representation

Figure 3 gives an overview of the CEM framework, which consists of two main parts:

Part 1 is a customer experience design and implementation process, consisting of four stages. The stages are sequential (as indicated by the black arrows between the stages in Figure 3), but also iterative (as indicated by the curved arrow on the left), since customer needs and requirements constantly change. Customer needs must be re-evaluated periodically to ensure that the enterprise is still aligned to deliver on the customer's expectations.

Five building blocks are required for organisational readiness in support of the customer experience process, as indicated in Part 2 of Figure 3. These building blocks are not sequential. However, the double-sided black arrow between Part 1 (on the left) and Part 2 (on the right) indicates that there is a dependency between the implementation process and the building blocks.

5.2 Framework detail

In this section, more detail is provided for Part 1 (see Table 3) and Part 2 (see Table 4) of the CEM framework, describing the detailed actions/guidelines, tools, and techniques that are suggested, and the desired outcomes expected for each phase or building block. Table 4 provides detail on the organisational elements in support of the customer experience implementation process.

6 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

CEM is becoming a strategic focus area, especially within the telecommunications industry. Yet a preliminary survey conducted by Du Plessis [8] to assess the maturity of CEM in telecommunication companies in South Africa indicated a gap between current theoretical CEM approaches and their practical implementation. In the search for a comprehensive CEM approach, this paper presented the results of a systematic literature review of the existing CEM literature. From the literature review, key concepts for customer experience and CEM were defined. In addition, the literature on service and quality management, customer satisfaction, and perception management was synthesised within a single model, called the enterprise-customer service model (see Figure 2), which is also one of the contributions of this paper. The enterprise-customer service model consolidates the intricacies of the customer-enterprise relationship, and indicates that the service experience occurs at the point where the customer and the enterprise meet. Various enterprise capabilities and customer intentions or expectations have an impact on perceived quality. In addition, multiple moderators (consumer, macro-economic, enterprise, and situation) directly or indirectly influence perceived quality. The model also highlights five gaps that can have a negative effect on perceived quality.

The enterprise-customer service model created the necessary context for analysing existing CEM approaches (models and frameworks) and identifying nine common themes via inductive thematic analysis, while applying guidelines from Guest et al. [13]. The results of the inductive thematic analysis validated the existence of nine common themes. The results also indicated that no single approach addresses the nine themes comprehensively.

Following a design research approach to address the gap in the existing CEM literature, this paper presented a newly-developed artefact, a holistic CEM framework, as its main contribution. Using the nine themes identified during the inductive thematic analysis and the guidelines of Offermann et al. [14] on method design, a creative process was followed to construct the CEM framework components.

The CEM framework, which consists of two parts, is intended to be applied in all enterprises and all industries, and is useful to managers and practitioners who are concerned with improving customer experiences. Part 1 of the CEM framework provides a customer experience design and implementation process, while Part 2 provides prerequisite building blocks that ensure organisational readiness in support of the customer experience process (Part 1).

Derived from nine common themes in the literature, the CEM framework is a theory-ingrained artefact that consolidates existing fragments of CEM practices, tools, and techniques in a holistic framework. Future work is required to evaluate the utility and validity of the framework by implementing it in a telecommunications enterprise.

REFERENCES

[1] Heskett, J.L. 1997. The service profit chain: How leading companies link profit and growth to loyalty, satisfaction and value. Simon & Schuster. [ Links ]

[2] Heskett, J.L., Jones, T.O., Loveman, G.W., Sasser, W.E. and Schlesinger, L.A. 1994. Putting the service- profit-chain to work, Harvard Business Review, March-April 1994. pp164-170. [ Links ]

[3] Manning, H. and Bodine, K. 2012. Outside in: The power of putting customers at the center of your business. Boston NY: Forrester Research. [ Links ]

[4] O'Grady, V. 2011. Africa insights: Sustainable margins through innovations. New Jersey, USA: TM Forum. [ Links ]

[5] Rich, R. 2012. Customer experience: Assuring service quality for every customer. Tm Forum Insights Research. New Jersey, USA: TM Forum. [ Links ]

[6] Meyer, C. and Schwager, A. 2007. Understanding customer experience. Harvard Business Review. February,85(2), pp 117-126. [ Links ]

[7] Rae, J. 2006. The importance of great customer experiences. Bloomberg Business Week Magazine. Posted on November 26, 2006, [ Links ]

[8] Du Plessis, L. 2015. A customer experience management framework for enterprises: A telecommunications demonstration. Masters thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. [ Links ]

[9] Burns, M. 2012. The state of customer experience. Cambridge, MA, USA: Forrester Research, Inc. [ Links ]

[10] Vaichnavi, V. and Keuchler, B. 2012. Design science research in information systems. Retrieved from http://desrist.org/design-research-in-information-systems.[Accessed 11 April 2014] [ Links ]

[11] Hidalgo Landa, A., Szabo, I., Le Brun, L., Owen, I. and Fletcher, G. 2011. Evidence-based scoping reviews. The Electronic Journal Information Systems Evaluation, 14(1), pp. 46-52. [ Links ]

[12] Colicchia, C. and Strozzi, F. 2012. Supply chain risk management: A new methodology for a systematic review. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17(4), pp. 403-418. [ Links ]

[13] Guest, G., Macqueen, K.M. and Namey, E.E. 2012. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE. [ Links ]

[14] Offermann, P., Blom, S., Levina, O. and Bub, U. 2010. Proposal for components of method design theories. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 2(5), pp. 295-304. [ Links ]

[15] Fiegen, A.M. 2010. Systematic review of research methods: The case of business instruction. Reference Services Review, 38(3), pp. 385-397. [ Links ]

[16] Pine, B. and Gilmore, J. 1998. Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review. July-August 1998, pp. 97-105 [ Links ]

[17] Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. and Berry, L.L. 1985. Conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. The Journal of Marketing, 49(4), pp. 41 -50. [ Links ]

[18] Zeithaml, V.A. 1988. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), pp. 2-22. [ Links ]

[19] Berry, L.L., Carbone, L.P. and Haeckel, S.H. 2002. Managing the total customer experience. MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2002, pp. 85-89. [ Links ]

[20] Schmitt, B.H. 2003. Customer experience management: A revolutionary approach to connecting with your customers. Wiley. [ Links ]

[21] Card, A. and Cova, B. 2003. Revisiting consumption experience: A more humble but complete view of the concept. Marketing Theory, 3, pp. 267-286. [ Links ]

[22] Shaw, C. 2005. Revolutionize your customer experience. Palgrave Macmillan Publishers. [ Links ]

[23] Blanchard, K., Ballard, J. and Finch, F. 2004. Customer mania! It's NEVER too late to build a customer- focused company. New York, USA: Free Press. [ Links ]

[24] Galbraith, J.R. 2005. Designing the customer-centric organization. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

[25] Zarantonello, L., Schmitt, B.H. and Brakus, J.J. 2007. Development of the brand experience scale. Advances in Consumer Research, 34, pp. 580-582. [ Links ]

[26] Frow, P. and Payne, A. 2007. Towards the 'perfect' customer experience. The Journal of Brand Management, 15(2), pp. 89-101. [ Links ]

[27] Gentile, C., Spiller, N. and Noci, G. 2007. How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European Management Journal, 25(5), pp. 395-410 [ Links ]

[28] Grewal, D., Levy, M. and Kumar, V. 2009. Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), pp. 1-14. [ Links ]

[29] Mosley, R. W. 2007. Customer experience, organisational culture and the employer brand. The Journal of Brand Management, 15(2), pp. 123-134. [ Links ]

[30] Harris, P. 2007. We the people: The importance of employees in the process of building customer experience. The Journal of Brand Management, 15(2), pp. 102-114. [ Links ]

[31] Voss, C. and Zomerdijk, L. 2007. Innovation in experiential services - An empirical view. Department of Trade and Industry - Innovation in Services, 9, pp. 97-134. [ Links ]

[32] Patricio, L., Fisk, R.P. and Falcäo e Cunha, J. 2008. Designing multi-interface service experiences: The service experience blueprint. Journal of Service Research, 10(4), pp. 318-334. [ Links ]

[33] LRA Worldwide. 2007. CEM methodology. LRA Worldwide. [ Links ]

[34] Fisk, P. 2009. Customer genius. Chichester, UK: Capstone Publishing Ltd. [ Links ]

[35] Verhoef, P.C., Lemon, K.N., Parasuraman, A., Roggeveen, A., Tsiros, M. and Schlesinger, L.A. 2009. Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of Retailing, 85(1), pp. 31-41. [ Links ]

[36] Lemke, F., Clark, M. and Wilson, H. 2011. Customer experience quality: An exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(6), pp. 846-869. [ Links ]

[37] Klaus, P.P. and Maklan, S. 2012. EXQ: A multiple-item scale for assessing service experience. Journal of Service Management, 23(1), pp. 5-33. [ Links ]

[38] Shaw, C., Dibeehi, Q. and Walden, S. 2010. Customer experience: Future trends and insights. Palgrave Macmillan New York, New York [ Links ]

[39] Nasution, R.A., Sembada, A.Y., Miliani, L., Resti, N.D. and Prawono, D.A. 2014. The customer experience framework as baseline for strategy and implementation in services marketing. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 148 pp. 254-261. [ Links ]

[40] Zomerdijk, L.G. and Voss, C.A. 2010. Service design for experience-centric services. Journal of Service Research, 13(1), pp. 67-82. [ Links ]

[41] Patricio, L., Fisk, R.P., Cunha, J.O.F.O.E. and Constantine, L. 2011. Multilevel service design: From customer value constellation to service experience blueprinting. Journal of Service Research.14 (2), pp. 180-200 [ Links ]

[42] Kamaladevi, B. 2009. Customer experience management in retailing. Business Intelligence Journal, 3(1), pp. 37-54 [ Links ]

[43] Palmer, A. 2010. Customer experience management: A critical review of an emerging idea. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(3), pp. 196-208. [ Links ]

[44] Johnston, R. and Kong, X. 2011. The customer experience: A road-map for improvement. Managing Service Quality, 21(1), pp. 5-24. [ Links ]

[45] Clatworthy, S. 2012. Bridging the gap between brand strategy and customer experience. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 22(2), pp. 108-127. [ Links ]

[46] Manning, H. and Bodine, K. 2012. Outside in: The power of putting customers at the center of your business. Boston NY: Forrester Research. [ Links ]

[47] Mummigatti, V.S. 2012. Customer experience transformation - A framework to achieve measureable results. In: Fischer, L. (Ed.), Delivering the customer centric organisation: Real-world business process management. Florida, USA: Future Strategies Inc., pp. 51-60. [ Links ]

[48] Leather, D. 2013. The customer-centric blueprint. Johannesburg, South Africa: REAP Publishing. [ Links ]

[49] Newbery, P. and Farnham, K. 2013. Experience design - A framework for integrating brand, experience and value. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [ Links ]

[50] Walker, S. 2014. Walkerinfo. Walker Information Inc. [ Links ]

[51] Berry, L.L. and Carbone, L.P. 2007. Build loyalty through experience management. Quality Progress, September 2007, pp. 26-32. [ Links ]

[52] Brakus J.J., Schmitt, B.H., and Zarantonello, L. 2009. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), pp. 52-68. [ Links ]

[53] Bitner, M.J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), pp. 57-71. [ Links ]

Available online 11 Nov 2016

Presented at the 27 annual conference of the Southern African Institute for Industrial Engineering (SAIIE), held from 27-29 October 2016 at Stonehenge in Africa, North West, South Africa.

* Liezl.duplessis@knotion.net

# The author was enrolled for an M Eng (Industrial) degree in the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, University of Pretoria

† The author was enrolled for a D Phil (Engineering Management) degree in the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, University of Pretoria