Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

On-line version ISSN 2224-7890

Print version ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.27 n.1 Pretoria May. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7166/27-1-1114

CASE STUDIES

The effect of a Project Management Office on project and organisational performance: A case study

J. van der Linde; H. Steyn*

Department of Engineering and Technology Management, Graduate School of Technology Management University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Depending on the specific needs of the host companies, Project Management Offices (PMOs) are created and mandated for different reasons. As a result of varying mandates and functions of PMOs, there is no agreed method to determine the value of a PMO. By studying the case of an organisation that recently implemented a PMO, this paper provides some insight into ways to determine the value of a PMO. Three new methods for determining the value of a PMO are proposed.

OPSOMMING

Projekbestuurkantore (PKe) word geskep en ontvang mandate vir verskillende redes wat bepaal word deur die spesifieke behoeftes van die gasheer maatskappy. As gevolg van die verskille in mandate en funksies van PKe, bestaan daar tans geen algemeen aanvaarde metode om die waarde van 'n PM te bepaal nie. Deur die studie van 'n geval van 'n- organisasie wat onlangs 'n PK geïmplementeer het, bied hierdie artikel insig oor maniere waarop die waarde van 'n PK bepaal kan word. Drie nuwe metodes vir bepaling van die waarde van 'n PK word voorgestel.

1 INTRODUCTION

Although the concept of a project management office (PMO) or project office (PO) has been around for many years, the functions, purposes, and definitions of these offices have changed over time. The PMO evolved from a project office (PO) that was responsible for one project or programme, usually a major government-funded project (1950-1990), to the more multi-project management scenarios currently found [1]. The PMO keeps evolving and changing as the needs of industry change and as new principles and methodologies are developed. It is therefore necessary for a PMO to change and adapt continually to an organisation's needs in order to remain valuable [2].

Currently, the project management discipline is involved in a wide variety of industries. The functions and purposes of PMOs are also varied to the extent that there is no single scheme that can describe the ideal set of functions and purposes of the PMO [3]. The variations are obvious from the various definitions of a PMO. For example, the definitions given for a PMO in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) varies between the 4th (2008) and 5th (2013) editions [4,5]. The former mentions that the role of a PMO can range from providing support functions to being responsible for the direct management of projects, while the latter emphasises standardisation and facilitating the sharing of resources, methodologies, tools, and techniques. Ward, as cited by Dai and Wells [6], gives a third definition of the PMO, which includes 'strategic matters'. This is interpreted as a mandate that includes the function of project portfolio management.

The mandate of the PMO selected for this case study is a combination of the three types mentioned above. First, it is a mutli-project PMO or Project Portfolio Management Office (PPMO) that is responsible for providing project support and managing projects and programmes directly. It also includes a Centre of Excellence (CoE) that is the custodian of the project management governance, methodologies, tools, and techniques, and provides strategic management input to the organisation.

Hobbs and Aubry [3] support the point that there is a large variability in the roles, function, structures, and legitimacy of PMOs between organisations. From their survey of 500 organisations, they realised that PMOs found in industry vary significantly from what is found in the literature. The main differences lie in the structures and roles/functions of the PMO, as well as the perceived value of the PMO.

The reason why there is such variation in the structures and roles of PMOs is that there is no 'one-size-fits-all' solution. PMOs are structured and mandated according to the needs of the organisations within which they function; thus no two PMOs are the same. This makes the task of measuring the impact of or value added by the PMO difficult; each PMO adds value in different ways. Unless an appropriate method of determining the value of a PMO is used, invalid conclusions can be reached about the value that a specific PMO contributes. Therefore, the objective of this paper is to shed some light on ways to determine the value of a PMO.

Unger et al. [7] state that the roles of PMOs and the impact of these roles in terms of value creation are unclear. They even claim that there is no empirically validated evidence that the involvement of PMOs in project management has increased project performance or organisational performance. The lack of empirical evidence for PMOs in general is understandable, given that the functions and purposes of the PMO are so varied. The value added by a PMO is as varied as the functions of the PMOs.

Unger et al. [7] claim that a PMO adds value to an organisation and to a portfolio of projects; in their work, they propose alternative methods to determine the value added by a PMO. They link the specific roles of a PMO to the value created by each role.

Aubry et al. [8] summarise various methods that have been used in the literature to attempt to measure the value or performance of a PMO. These methods include the return on investment (ROI) of a PMO, a pragmatic method, the balanced score card method, and success factors.

The financial measures are problematic. For example, the ROI of a PMO is very difficult to determine, as a PMO generally does not contribute directly to the bottom line of an organisation. With the pragmatic measures defined by Aubry et al. [8], the value of the PMO is also very difficult to determine. The balanced score card method is based on ROI and thus has the same problems as other financial measures. The success factors contribute to the understanding of the conditions that might lead to success, but they do not give an indication of the performance of a PMO.

The roles, value, and legitimacy of PMOs in industry are varied to the extent that there is no empirical validation for the performance increase due to a PMO, or of the value created by a PMO [3,7]. The literature also provides ambiguous views about the value of a PMO [9]. Many PMOs are found not to add value, or to add very little value, especially if the direct return on investment is used as a measure.

The literature that indicates that PMOs do add value claims that PMOs add value in ways other than a direct financial benefit. For example, Unger et al. [7] indicate that the PMOs they studied showed improvements in resource allocation and commitment, cooperation improvement between projects, improved quality of information sent to management for decision-making, and improved single-project performance. Hobbs and Aubry [3] also mention that one value-adding benefit of a PMO is that it improves the project management maturity of an organisation.

Hurt and Thomas [9] indicate that the establishment of project management principles and practices under the management of a PMO can have benefits that include cost savings, increased revenue, reduced rework, improved competitiveness, attainment of strategic objectives, strategic alignment, more effective use of human resources, improved general use of resources, and better project decision-making.

2 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

The objective of this paper is to shed some light on ways to determine the value that PMOs can have for their host organisations, by studying the effect that a specific PMO has on its host organisation. A before-and-after case study was performed on this organisation; by comparing the project environment before and after the establishment of the PMO, this study is able to indicate the impact that the PMO is perceived to have had on the organisation.

It is proposed that there are unexplored ways of determining the value of a PMO. It is also proposed that the value of a PMO can be determined by analysing the impact that a PMO has on an organisation, and that the value of the PMO can be linked to the functions it is mandated to perform.

In the process of exploring ways to determine the value of a PMO, the following questions related to the case were answered:

1. Why has the specific PMO been created in the host organisation? In other words, what is the purpose of the PMO?

2. What functions is the PMO mandated with?

3. What impact or effect is the PMO perceived to have on the organisation, its projects, and portfolio of projects?

4. Does the PMO fulfil its purpose?

5. What value was added by the PMO?

Question 1 is the starting point in determining the impact or value of the PMO. If the purpose of the PMO is known, its value lies in whether it fulfils its purpose or not (Question 4). Thus, if the answer to Question 1 is known, and Question 4 can be answered positively, then the PMO has added value. Questions 2 and 3 are asked in order to determine exactly what value was added and how this value can be determined. Questions 2 and 3 are also used as inputs in a proposed model that is used to link the functions of the PMO with its value.

3 THE CASE

The subject of this case study is a diversified South African mining company. The company is not a project-based organisation: its core business is operations, and projects are executed only to support, improve, or expand the operations. The company established a PMO in 2012. The PMO includes an Enterprise Project Management Office (EPMO) at its corporate head office, with a project management CoE and several regional PMOs at the business units.

For this case study, the unit of analysis is the entire project management environment within the company; it includes the EPMO as well as the regional PMOs. The PMO is a multi-project PMO, or PPMO, that fits into Hobbs and Aubry's third typology of PMOs [10]: a PMO with project managers, a mandate including all of the organisation's projects, and a moderate level of decision-making authority.

4 CONCEPTUAL MODEL USED

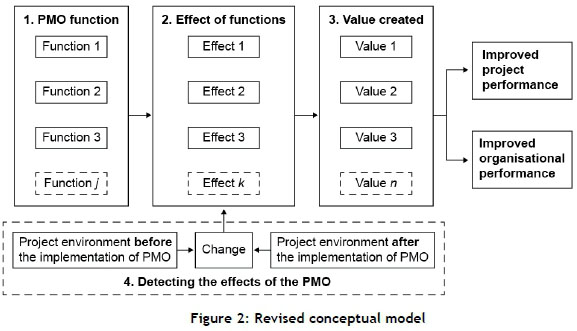

One of the propositions made is that the functions of the PMO can be linked to the value created by the PMO. In order to do this, the conceptual model in Figure 1 was proposed. The model starts with the functions with which the PMO is mandated (1). These functions have certain effects on the organisation and its projects (2). The effects add some value to the organisation (3) that can be either positive or negative. The value added by the PMO will influence the project and organisational performance.

By comparing the project environment before the implementation of the PMO with the project environment after the implementation of the PMO, a change is evident. By analysing the change, the effects of the PMO (4) can be determined.

5 RESEARCH METHODS

The methodology employed in this research is a pre-post type case study: the organisation was examined before and after the implementation of the PMO. Various methods of data gathering were used, including interviews, archived data, direct observation, and participant observation. Each research question required a different method or methods to obtain the answer.

5.1 Research Question 1 : Why was the PMO created?

In order to answer this question, interviews were held with the manager of the current PMO CoE and members of the original Community of Practice (CoP) that was established before the PMO was created. Interviews with key management personnel were also held to determine the rationale behind the establishment of the PMO and problems that needed to be solved. Semi-structured interviews were conducted.

Very few sources that explicitly state why PMOs are created were found in the literature. Kerzner [1] indicates that the reasons for creating PMOs include increased coordination, improved information availability, improved resource utilisation, improved operational efficiency, improved control, and increased quality. Hurt and Thomas [9] indicate that PMOs are created to reduce the failure rate of projects, to gain more control over cost, to improve the predictability of project cost estimates, to be able to execute bigger and more complex projects, to improve project quality, and to improve confidence in the ability to execute projects. The PMO studied by Aubry et al. [8] was also created with the specific purpose of bringing about an organisational change.

This research question is a very important one to answer, as it is the starting point of creating a PMO. If a PMO is not created with a specific purpose in mind, an ad hoc approach will be followed to mandate the PMO, and the PMO will be destined to fail [3]. In order to study any similarities of the case under consideration with previous work, the interview results were compared with the reasons found in the literature for creating PMOs.

5.2 Research Question 2: What functions is the PMO mandated with?

The answer to this question was found in official company documentation. The official mandate of the PMO answered the question about the functions with which the PMO is mandated.

Several authors describe a variety of functions with which a PMO can be mandated [1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14]. The functions mentioned by the above authors overlap, but more than 30 different functions were identified. No single PMO will be mandated with all of these functions; a PMO will be mandated with the combination of these functions that best suits the organisation in which it is operating.

5.3 Research Question 3: What impact is the PMO perceived to have on the PMO?

This question was the most difficult one to answer, and several methods were used to obtain the answer. One effect a PMO has on an organisation is that it improves the project management maturity level of the organisation [3]. In order to determine what effect this particular PMO had on the subject organisation, the Project Management Institute's (PMI) Organisational Project Management Maturity Model, or OPM3®, was used to determine the project management maturity of the organisation before and after the implementation of the PMO.

The organisation had used the OPM3 model to establish project management maturity before the implementation of the PMO, and the measurements were repeated two years after the implementation of the PMO in order to obtain comparative results. The first survey was conducted during 2010, two years before the establishment of the PMO in 2012; the second survey was conducted in 2014, two years after the implementation of the PMO. As a change in project management maturity of the organisation cannot necessarily be assumed to be caused by the implementation of the PMO, this method was supplemented by other methods.

Other methods to answer this question included interviews, archival data, direct observation, and participant observation. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with key personnel in the company to determine the effect that the PMO had on the company. The interviewees included senior management, PMO management, PMO clients, PMO personnel, and some key personnel outside of the project management environment, such as financial accountants.

Archived data and official company documentation were studied to determine the changes made in the company's structures, as well as in changes in Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) used to measure the performance of the project portfolio. Projects executed under the new methodologies and governance processes were also observed and compared with projects executed before the PMO had been established, in order to determine whether there were any differences in project outcomes.

5.4 Research Question 4: How does the PMO fulfil its purpose?

The answer to this question was derived from the semi-structured interviews.

5.5 Research Question 5: What value is added by the PMO?

This question was answered by analysing the effects/impacts that were determined from Research Question 3. The perceived value of the PMO was discussed during the interviews. Direct observation was also used to determine the value of the PMO.

6 RESULTS

6.1 Research Question 1 : Why was the PMO created?

The company that is the subject of this study was formed after a large company had been unbundled into two separate companies. The company under consideration was one of these two companies, and it also acquired assets from a third company. The business units that were acquired by the company after the split did not have any project management structure or background, while the business units that were part of the original company did have project management experience and structure; however, the original company did not have any standardised project management language, methodology, or governance processes. Many other deficiencies and problems in the project management environment were also brought to light. The consequences of these deficiencies and problems included the following:

• Poor use of resources.

• Projects were not meeting deadlines due to slow execution rates.

• Cash flow forecasting and capital budgeting was a problem.

• The company was unable to spend its capital budget, resulting in projects rolling over year after year.

• There was no coordination between projects or between projects and operations.

• Portfolio management was not possible, resulting in a random approach to allocating and managing capital; this put the entire organisation at risk.

• Project plans and progress were not visible, thus making strategic decision-making, integration and portfolio management very difficult or impossible.

• No due diligence was followed when executing projects, which resulted in delays, cost increases, and poor quality deliverables.

• Resource management was ad hoc, resulting in a mismatch between the resources and the number of projects that needed to be executed; this resulted in overloading project managers and slow project execution.

• The large volume of capital projects could not be executed.

Simply put, the PMO was created to solve the above problems and to address the shortcomings of the project environment that existed before the implementation of the PMO. This particular PMO was built around the guidelines given by Hill [15] and Boles and Hubbard [16].

When the reasons for creating this particular PMO were compared with those in the literature, it was found that all the reasons for creating a PMO according to Kerzner [1] and Hurt and Thomas [9] were applicable. This establishes that the problems found in the literature and those experienced in other organisations are similar to those experienced in this case.

6.2 Research Question 2: What functions is the PMO mandated with?

The mandate of the PMO includes the following functions:

• Implement, run, and maintain an Enterprise Project Management (EPM) system that allows all project information to be stored and displayed from a single source, so as to provide a single consolidated view of all projects.

• Ensure accurate and timely information availability and ensure project visibility, including tracking and reporting on project delivery.

• Facilitate portfolio selection, prioritisation, and optimisation.

• Recruit/select programme and project managers and other project resources.

• Provide support to programme and project managers in the form of document control and knowledge management, project cost control, resource coordination, planning and scheduling, risk management, training, and project administration.

• Train and coach programme and project managers and project teams in the methodologies and knowledge areas of project management, as well as in the systems used in the project environment.

• Set up temporary programme and project offices where required.

• Serve as CoEs that provide relevant methodologies, standards, templates, and tools.

• Provide integrated governance across programmes and projects.

• Perform health checks on programmes and projects when required by the Executive Committee; this includes project auditing and recovery of projects that are at risk.

• Ensure due diligence on the execution of projects and programmes.

When these functions are compared with those found in the literature [1,3,12,14], it can be seen that not all of the functions indicated in the literature are applicable to this PMO. This supports the notion that each organisation has its own needs and problems that need to be solved, and will mandate its PMO to solve its specific problems. There is no generic, one-size-fits-all set of functions for a PMO, even though there are overlaps and a number of generic functions.

6.3 Research Question 3: What impact is the PMO perceived to have on the organisation?

The establishment of this PMO brought about significant changes in the organisation. One of the biggest changes was the implementation of a specified project management methodology and governance. A standardised project life cycle process (PLP) was also established, which was developed for industry best practices and dictates the lifecycle and gate review process.

An EPM system was implemented to support this methodology and the entire project managing environment. This system provides the necessary tools to everyone involved in projects to function according to the methodology and governance. This system supports all the functions of the PMO, and is linked to other enterprise software to form an integrated enterprise system.

According to the managers who were interviewed, one of the biggest advantages and attributes of the PMO is the visibility of project plans, progress, and tracking of projects. Due to the standardised project reporting systems, accurate project information is available from the system, allowing for better decision-making and coordination between projects.

With the implementation of the PMO also came the tools and methodologies to support project portfolio management. A new project management process was developed and implemented.

Since the implementation of the PMO, there are now specialist project managers; no longer do engineers alone have to do both project management and engineering. Other specialist functions are also now included in the project support roles, such as planning and scheduling, construction supervision, document control, cost control, and resource coordination.

Before, projects were executed in isolation with very little coordination. The effects of one project on another were not taken into consideration. Currently, there is better coordination and integration between projects. The effects of one project on another, and the effects on future expansions are being considered. Interfaces between projects and between projects and operations are better defined and managed.

One of the functions of the PMO is to conduct project audits. If projects are found to be non-compliant, the situation must be rectified within a certain period of time. If a project is found to be severely behind schedule or if major deficiencies are found, the PMO can assist in recovering the project and getting it back on track and up to standard.

It seems that the PMO had a dramatic effect on the project management maturity of the organisation. There might be other factors that influenced the project management maturity, but the establishment of the PMO was the only significant change that took place within the project management environment of the organisation. Based on the comparison of the OPM3® surveys that were done in 2010 (before the PMO) and in 2014 (after the PMO), the overall organisational project management maturity has increased from 22 per cent to 44 per cent, while the project management maturity has increased from 24 per cent to 69 per cent. All 39 best practices for project management were achieved, compared with only four in 2010. Programme management maturity has increased from 0 per cent to 22 per cent and portfolio management maturity from 10 per cent to 18 per cent. The organisational enablers improved from 53 per cent to 76 per cent. No explanation for this improvement in maturity, other than the implementation and work done by the PMO, could be found.

A KPI that is used to measure the performance of the portfolio of projects of this company is 'capital spending accuracy'. It is the actual capital expenditure expressed as a percentage of the capital budgeted for a given year. This KPI showed a significant improvement since the implementation of the PMO. It improved from an average of 50 per cent to 81 per cent in the year that the PMO was established. The following year, a 90 per cent spending accuracy was achieved. The improvement of this KPI indicates an improved ability of the company to execute its projects.

The improvements and the problems that were solved by the PMO include the following:

• Better use of resources.

• There are specialist project management and support functions.

• There are methodologies and governance processes in place.

• Better coordination and integration. There are specific forums for the coordination and integration of projects.

• There is better project planning and risk management.

• Project plans and progress are visible.

• Portfolio management is made possible.

• Sufficient data is available to pair a project manager with a suitable project.

• There is a project repository for all project-related information, including lessons learned.

Establishing a PMO also had several negative impacts. The biggest negative impact was the increase in cost. The cost of the PMO is allocated to individual projects so that the cost of the PMO can be capitalised. This extra project management cost allocated to each project made some smaller projects less economically viable. Another problem that was encountered and that persists two years after implementation is the resistance to change. The new methodologies and governance processes are not easily adopted. Some inter-departmental tension and culture clashes are also caused by the new methodologies and governance processes. This is very similar to the problems described by Pellegrinelli and Garagna [2], where the functions and 'powers' of the PMO led to internal political problems.

6.4 Research Question 4: How does the PMO fulfil its purpose?

Comparing the problems that were encountered before the implementation of the PMO and the problems that were actually solved, it is clear that the PMO does fulfil its purpose. The general consensus among interviewees also confirmed that the PMO does fulfil its purpose, but that it has not yet reached its full potential. The reasons for this are that the PMO is severely understaffed, the PMO skill level of personnel is not up to standard yet, not all support functions are available because the PMO is still in a growing phase, and resistance to change is hampering progress.

6.5 Research Question 5: What value is added by the PMO?

Various problems were present in the project management environment before the implementation of the PMO. The PMO was, among other reasons, created to solve these problems. It was found that after the implementation of the PMO, most of these problems had been solved or partially solved.

With the implementation of the PMO came various new systems, tools, and procedures that enabled the organisation to manage its portfolio of projects better. The biggest contributions were the visibility of project plans and progress, the ability to forecast project spending and benefits over a number of years, and the ability to align projects with the business strategy.

With the establishment of the PMO also came various forums that are specifically aimed at project integration and coordination. The coordination between projects resulted in large savings in capital.

The establishment of the PMO significantly increased the project management maturity of the organisation. According to Saures, cited in Skulmoski [17], increased maturity indicates the increased importance of project management to an organisation. Even though an increase in maturity will not guarantee project success [13,18], it should improve the chances of project success [19]. It is also an indication of an increase in the number of support systems that are in place to aid a project. According to Anderson and Jessen [20], increased maturity means that an organisation is in a better position to use projects to reach its goals.

The PMO drastically improved the organisation's ability to execute its capital projects and improve its capital budgeting and spending accuracy.

6.6 Linking the value of the PMO with the functions of the PMO

By answering the research questions, the different fields in Figure 1 can be populated. Displaying the results of the research in this format shows the value of each function. However, it must be realised that no single function can truly add value in isolation from the other functions. For instance, the tools and systems will be useless unless they are combined with the methodologies or the support functions to run this system. Similarly, the methodologies cannot add value without the systems and project support functions to support its implementation.

Each function on its own can add value, but the true value of the PMO lies in the synergy between the functions. In this specific case, the improvement in the capital spending accuracy is not the result of one specific function. It is the synergy between all the functions that contributed to this value. Figure 1 can be revised to indicate that the values are as a result of the combination of functions; this is shown in Figure 2.

7 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

7.1 Conclusion

The PMO studied had a dramatic effect on the organisation. Many systems and methodologies were put in place at one time with noticeable effects on the organisation. Although the true potential of this PMO has not been reached yet, the PMO is perceived to add value overall. This study indicates three new ways that can be considered to determine the value of a PMO.

First, the value of a PMO starts with the reasons for creating the PMO. If it was created for a specific purpose and it fulfils that purpose, then it does add value. In this case, the PMO was to a large extent created to solve certain problems. It was found that the majority of these problems were in fact solved or at least partly solved.

A second way of determining the value of the PMO is to determine the value of the capabilities that the PMO provides to the organisation. In this particular case, the PMO gave the organisation the ability to manage a project portfolio. This specific ability is also not fully used yet, but it has already been of great value to the organisation. This can be seen in the increased coordination and integration of projects and the number of strategic projects in the pipeline. The ability to allocate capital to support the organisation's strategy is further proof of this ability. Amongst the functions of the PMO is the establishment and maintenance of project management support systems, including methodologies, tools, and techniques. This function of the PMO directly influences the project management maturity of the organisation. The value of the PMO lies in the continuous improvement of the maturity level of the organisation. A higher maturity level means that the organisation is more supportive of its projects and there is a larger chance of success. In this case, a marked increase in maturity was determined during the period that the PMO was established.

A third way of determining the value of the PMO, in a more quantitative way, is to measure the improvement of specific KPIs that are used to measure the performance of the portfolio of projects. For this particular case, the performance of the project portfolio or the organisation's ability to execute its projects was measured by the accuracy of predicting capital spending. With the implementation of the PMO, this KPI performance measure drastically improved.

This study supports the proposition that there are more ways of determining the value of a PMO than merely considering the direct financial implications. It further illustrates that the value of a PMO can be determined by analysing the impact that the PMO has on an organisation, and that the value of the PMO can be linked to its functions.

The value of the PMO studied lies in the impact it had on the organisation and the changes it brought about. The impact this PMO had on the organisation includes solving specific problems, giving the organisation the ability to do portfolio management, improving integration and coordination in the project environment, and improving project management maturity. One of the biggest changes that were brought about was the improvement in a specific KPI that is used to measure the performance of the company's project portfolio and its ability to execute its projects.

A conceptual model was devised and used to link the functions of the PMO with the value created. An observation that was made from using this model is that the value of the PMO results from the synergy between the functions.

7.2 Recommendations

Hobbs and Aubry [3] indicate that a large number of PMOs are closed down within a short period of time after their establishment. This gives rise to the criticism that PMOs are not sustainable. It is thus recommended that the sustainability of the PMO that was studied be evaluated from time to time to determine whether this criticism applies to this PMO.

The impact of this PMO should be re-evaluated in a number of years to determine whether it does in fact reach its full envisaged potential. The evolution of the PMO should also be studied as the needs of the company change. This is likely to confirm the comments made by Pellegrinelli and Garagna [2] about the need for a PMO to keep evolving in order to remain viable and to continue to add value.

The relationship between the different PMOs of the hosting organisation can be studied to determine its impact on the project environment of the organisation. The relational typologies and relationships described by Müller et al. [21] can be studied and applied to this case.

One of the functions of the PMO is to establish and maintain standardised methodologies in an organisation. The problem of having standardised and very strict methodologies, however, is that it takes away the autonomy of the project manager and might actually become a burden instead of a support. Further research is required on the correct balance of standardisation and flexibility of methodologies.

The findings of this research should be applied to different cases to test their validity and applicability. The conceptual model used can also be applied to other cases to test its usefulness in aiding in the thinking process to determine the value or impact of a PMO.

REFERENCES

[1] Kerzner, H. 2003. Strategic planning for the project office. Project Management Journal, 34(2), pp. 13-35. [ Links ]

[2] Pallegrinelli, S. & Garagna, L. 2009. Towards a conceptualisation of PMOs as agents and subjects of change and renewal. International Journal of Project Management, 27(7), pp. 649-656. [ Links ]

[3] Hobbs, B. & Aubry, M. 2007. A multi-phase research program investigating project management offices: The results of Phase 1. Project Management Journal, 38(1), pp. 74-86. [ Links ]

[4] Project Management Institute (PMI). 2008. A guide to the project management body of knowledge. 4th edition, Project Management Institute. [ Links ]

[5] Project Management Institute (PMI). 2013. A guide to the project management body of knowledge. 5th edition, Project Management Institute. [ Links ]

[6] Dai, C.X. & Wells, W.G. 2004. An exploration of project management office features and their relationship to project performance. International Journal of Project Management, 22(7), pp. 523-532. [ Links ]

[7] Unger, B.N., Gemunden, H.G. & Aubry, M. 2012. The three roles of a project portfolio management office: Their impact on portfolio management execution and success. International Journal of Project Management, 30(5), pp. 608-620. [ Links ]

[8] Aubry, M., Hobbs, B. & Thuillier, D. 2007. A new framework for understanding organizational project management through the PMO. International Journal of Project Management, 25(4), pp. 328-336. [ Links ]

[9] Hurt, M. & Thomas, J.L. 2009. Building value through sustainable project management offices. Project Management Journal, 40(1), pp. 55-72. [ Links ]

[10] Hobbs, B. & Aubry, M. 2008. An empirically grounded search for a typology of project management offices. Project Management Journal, 39, pp. 69-82. [ Links ]

[11] Pemsel, S. & Wiewiora, A. 2013. Project management office a knowledge broker in project-based organisations. International Journal of Project Management. 31(1), pp. 31-42. [ Links ]

[12] Marsh, D. 2001. The project and programme support office handbook. Project Manager Today Publications. [ Links ]

[13] Nicholas, J.M. & Steyn, H. 2012. Project Management for engineering, business, and technology. 4th edition, Routledge. [ Links ]

[14] Block, T.R. & Frame J.D. 1998. The project office - A key to managing projects effectively. Crip Publications. [ Links ]

[15] Hill, G.M. 2008. The complete project management office handbook. 2nd edition, Auerbach Publications. [ Links ]

[16] Boles, D.L.& Hubbard, D.G. 2007. The power of enterprise-wide project management. New York: Amcom. [ Links ]

[17] Skulmoski, G. 2002. Project maturity and competence interface. Cost Engineering, 43(6), pp. 11-18. [ Links ]

[18] Pretorius, S., Steyn, H. & Jordaan, J.C. 2012. Project management maturity and project management success in the engineering and construction industries in Southern Africa. South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 23(3), pp. 1-12. [ Links ]

[19] Project Management Institute (PMI). 2014. Pulse of the profession™: The high cost of low performance. Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute. [ Links ]

[20] Anderson, E.S. & Jessen, S.A. 2002. Project maturity in organizations. International Journal of Project Management, 21(6), pp. 457-461. [ Links ]

[21] Müller, R., Glückler, J. & Aubry, M. 2013. A relational typology of project management offices. Project Management Journal, 44(1), pp. 59-76. [ Links ]

Submitted by authors 15 Dec 2014

Accepted for publication 13 Feb 2016

Available online 10 /May 2016

The author was enrolled for a MEng (Project Management) degree in the Department of Engineering and Technology Management, Graduate School of Technology Management, University of Pretoria.

* Corresponding author herman.steyn@up.ac.za