Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

versión On-line ISSN 2224-7890

versión impresa ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.26 no.2 Pretoria ago. 2015

GENERAL ARTICLES

A strategic framework for improbable circumstances

D. KennonI,1 *; C.S.L. SchutteII

IDepartment of Industrial Engineering University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. dkennon@sun.ac.za

IIDepartment of Industrial Engineering University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. corne@sun.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Rare events, known as 'Black Swans', have determined the course of history. One of these was the global economic crisis of 2008. Such events highlight fields like strategic management and their shortcomings in helping to prepare organisations. The Strategic Framework for Improbable Circumstances was designed to add to the strategic management process by improving organisational preparation for these rare events. The framework was validated through interviews with experts who showed the need for such a framework, and who confirmed that it is a good first step for organisations to take towards addressing these Black Swan events.

OPSOMMING

Rare gebeurtenisse, ook bekend as 'Swart Swane', het die verloop van die verlede bepaal. Een van hierdie gebeurtenisse was die wêreldwye ekonomiese krisis van 2008. Hierdie Swart Swane het die fokus geplaas op strategiese bestuur, en op die tekortkominge van hierdie studieveld om besighede beter voor te berei om Swart Swane beter te hanteer. Die Strategiese Raamwerk vir Onwaarskynlike Omstandighede is ontwikkel as 'n byvoeging tot die strategiese bestuursproses deur die organisasie se voorbereiding vir hierdie tipe gebeurtenisse te verbeter. Die validasie van die raamwerk was gedoen deur onderhoude met deskundiges wat bewys het dat so raamwerk benodig word, en uitgewys het dat dit 'n goeie eerste stap was vir besighede om Swart Swane te trotseer.

1 INTRODUCTION

History is paved with events that, in the blink of an eye, have radically altered the way the world operates. These events 'come out of nowhere', and have a drastic impact globally on organisations and on the individuals who support and are supported by it [1].

The global economic crisis of 2008 [2] proved to be one of these rare events that had an extreme impact on the global economy. The crisis ensured that strategic management moved to the forefront as a 'new old buzzword'. The field of study up to that point had not changed much between the 2002 technology bubble and the 2008 crisis [3]; what had changed was the environment. Now boardroom strategists find themselves concerned that the priorities that have emerged from annual planning rituals do not address the demands of the increasingly volatile global business environment [4]. The markets are more volatile than before, and linear trend extrapolation as a substantial decision-making tool in analysis is now seen as a thing of the past. Every boardroom sees disaster scenarios being created -scenarios that, historically, would have been deemed unlikely; and the current trend increasingly looks more towards the preservation of liquid assets/cash as central to any strategy [4].

Industrial engineers are responsible for the analysis, design, planning, implementation, operation, management, and maintenance of integrated systems consisting of people, money, material, equipment, information, and energy [5]. The industrial engineer plays a crucial role, through the skills outlined above, in assisting organisations to interact with the global system through an integrated organisational system that consists of the elements identified above.

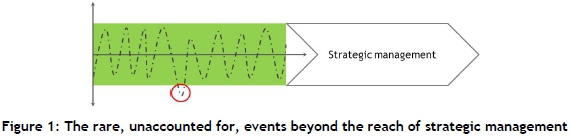

The Black Swan principle was initially introduced by N.N. Taleb in 2007. It opened up new possibilities for thinking about probabilities and the impact they carry [6] or the opportunities they create. The term 'Black Swans' arose from the incorrect assumption that 'all swans are white' - shown to be incorrect when black swans were discovered. 'Black Swans' were thus considered improbable events at that time; but they are now seen as a metaphor for something that should not exist [1]. The framework designed in this research takes a look at these Black Swans and the role they play in addition to the normal operational strategies that are designed in the process of strategic management (Figure 1).

Current strategic management focuses on the circumstances that play a role in day-to-day environmental business conditions; the improbable circumstances strategic (ICS) framework, presented here, focuses on the line beyond the green area, in the area of the improbable circumstance. The framework intentionally does not attempt to replace the current process of strategic management, but plays a role in supplementing it to improve strategic focus on the improbable circumstances.

2 STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT AND ITS CURRENT ROLE WITHIN THE ORGANISATION

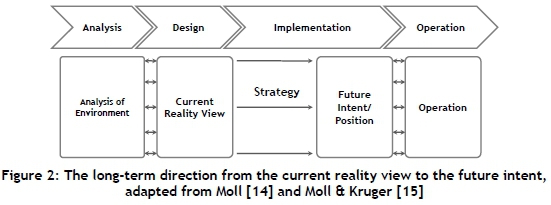

Strategic management has various definitions; the essence is distilled as the long-term survival of the organisation in order to achieve the organisation's goals through planning, running, and changing the organisation ([7], [8], [9], [10], [11] [12]). The long-term survival of the organisation is a function of competitive advantage, which results in a difference in value over its competitors [13]. It directs the focus on to the decisions and conditions that can be controlled in the present by keeping the uncontrollable future conditions in mind [14] & [15], as illustrated in Figure 2. Moll & Kruger [15] refer to business transformation as the step between design and operation; but for the purpose of this study, implementation is used as the step to transform design into operation.

The analysis of the environment is a process in which various tools can be used to gather and analyse data. The field of strategic analysis has been comprehensively researched over the last three decades, and can be found in the work of Grant [16], Pearce et al. [17], and Mintzberg et al. [18]. The information and understanding gained in the analysis phase of the strategic management process is used to design both a specific strategy and the objectives for this strategy. The strategy is then designed specifically for implementation in pursuit of the future intent. The operational phase of the strategic process needs to remain aligned with the objectives of the strategy, while at the same time assessing feedback on the current strategy and the next phase in strategy creation/improvement [14].

The fields of strategic management and industrial engineering can be combined to show a logical way to create strategies through the use of a systems approach. As described by Pearce et al. [17], strategy formulation can follow a sequential process that correlates with the process discussed by Moll [14]. Pearce et al. [17] formulated an approach to strategic management consisting of nine steps. Table 1 shows how these steps correlate with the process as discussed by Moll [14] in Figure 2.

The ICS framework that focuses on improving an organisation's preparation for the improbable circumstance will be discussed in section 4 below. That section also explains how proven strategic management tools can be used to address phases of the framework.

The reasoning behind this is 1) to indicate that the wheel, in some cases, has already been invented, and just needs some modifications to align it with the objectives of the phases; and 2) to form a type of validation to show that some tools that already exist could be used to aid in the improbable circumstance strategic formulation process.

As shown in Figure 1, there are events (considered improbable) that fall outside the realm of normal day-to-day processes, and so are not adequately covered by the strategic management process. These events, which may have an extreme impact, are known as 'Black Swans'.

3 THE IMPORTANCE OF ACKNOWLEDGING THE BLACK SWAN

Black Swan events gained popularity at the start of the global financial crisis of 2008, just after N.N. Taleb published his book Black Swans: The impact of the highly improbable. Taleb explained that the Black Swan has three main characteristics [1]:

1. It lies outside the realm of regular expectations;

2. Its consequences carry extreme impact (positive or negative); and

3. It is retrospective in its predictability.

Events such as tsunamis, the global economic crisis of 2008, and the 9/11 terrorist attacks are Black Swans, given their drastic impact and unexpected nature. These events were also retrospectively seen as predictable. Whether something is actually considered a Black Swan depends on your position and perspective, as illustrated by another metaphor used by Taleb - that of the Thanksgiving turkey [1]. The turkey, following normal farming practices, is fed well every day to ensure it is ready to be slaughtered for Thanksgiving. The turkey being slaughtered for Thanksgiving is a Black Swan event for the turkey. Considering the immediate historical events, there was no reason for the turkey to believe that it would not be fed that day, only to be slaughtered for the Thanksgiving meal. The farmer, on the other hand, sees this as a normal run-of-the-mill day, highlighting the fact that whether an event is a Black Swan or not depends on perspective and positioning [1].

Black Swans do not always carry detrimental consequences, as some consequences can be extremely beneficial. The example of the internet could be used: it was not initially built for people to connect and share knowledge, but was used as a military application, which then evolved [1].

The reason that so many humans and businesses are 'turkeys' is due to what Taleb called 'confirmation bias', which explains how we can state a theory and collect information to strengthen the conviction that we are correct, while we discard other information that contradicts our view. We generally have a naïve focus on historical observations as something definitive or representative of the future, and it is this that creates our inability to predict or expect Black Swans [19].

At present, preparations for improbable circumstances (or 'Black Swans') are inadequate as organisations try to predict, and thus prepare for, specific circumstances, rather than looking at coping with the improbable circumstance as a whole [20], [21], [22] & [23]. The result of this can be seen in the recession caused by the global financial crisis of 2008. Organisations need to understand how they and their industries will react to devastating or miracle-inducing improbable events.

3.1 Coping in order not to be a turkey

Taleb produced guidelines to support his notion that organisations can better prepare for the improbable circumstance [23].

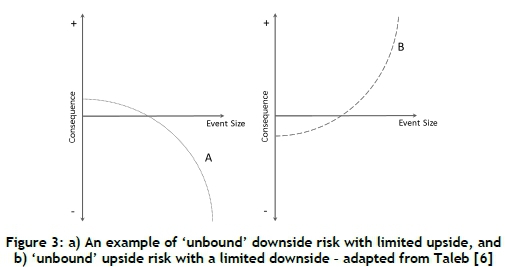

The main idea proposed to address Black Swans is to be hyper-conservative when you focus on downside risk (A in Figure 3), and hyper-aggressive when presented with opportunities that cost you very little (B in Figure 3).

Taleb observed that, in general, most organisations use dollars to create pennies; but the Black Swan coping philosophy is displayed through the return for risk B, shown in Figure 3, showing that one should bet pennies in order to make dollars [1]. Organisations that focus on mitigating the shock of catastrophes do not perform as well as other organisations on stock exchanges (such as the NASDAQ and the JSE) that do not have added expenses that cover increased cash reserves, insurance, and/or reduced leverage [1]. Critically, Taleb showed that organisations that enjoyed reduced expenses were most negatively affected during the crisis, compared with those requiring mitigating expenses, and thus were in a better financial position after the crisis.

Certain Black Swans are only Black Swans with the benefit of hindsight, as shown in the example of the turkey. The relationship between entities defines Black Swans as events that occur according to expectation. The global market, as an entity, has a fixed view of what needs to be known (on the balance of probabilities) and what does not need to be known; and the Black Swan principle reveals as significant the things that are not said.

Taleb is critical of scenario planning as, in his view, current strategists are constrained by the box in which they have been operating for years [1]. The result of these planning sessions can be whittled down to four or five scenarios with which you gamble by excluding others. Scenarios and forecasts should rather be used as a tool to see how fragile2 the organisation is in its environment. In the end, scenario planning should be used to create scenarios to test the fragility rather than to gamble on a forecast of events [1] & [24].

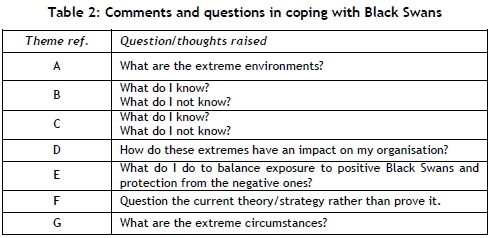

The main themes proposed by Taleb to deal with Black Swan events are [1] & [22]:

A. To keep your eyes open for Black Swans in order to be aware of the environments that border on extreme (much in the same way that Clem Sunter [24] highlights flags to indicate when a given event is becoming more probable);

B. To not be too attached to your beliefs when presented with evidence to the contrary. Dare to admit that you do not know;

C. To know the limits of your knowledge, and remain open to understanding where you can be a fool and where you cannot. Foolishness could be a dangerous way of acting, or it could mean nothing - it is a position of the relationship between entities;

D. That time periods in forecasting events cause errors to increase exponentially. The direction of focus should highlight consequences over exact probabilities;

E. To be exposed to Black Swans that provide opportunity while hedging against those that cause destruction. The possibility of serendipity should be maximised to ensure positioning that takes advantage of the opportunities created;

F. To search for signals that would refute or question a theory, rather than searching for evidence to build information that supports it; and

G. To look to history, but not to see history as a storybook for scenarios to predict the future, but rather to show how wrong we have always been with forecasting.

The points raised here have been used to form the backbone of the framework that, essentially, a company will use to improve its position ahead of a Black Swan event. The above themes were assigned alphabetical characters to reduce excessive referencing in the sections that follow.

3.2 Developing a framework to cope in a volatile world

The themes for dealing with Black Swans (as listed in the previous sub-section) raised some points or questions that need to be addressed by the organisation to improve its preparation for Black Swan events. These questions were also validated during the procedure of validating the framework, which is discussed in section 5.

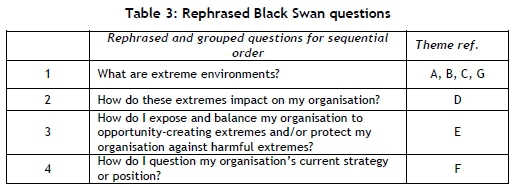

The questions in Table 2 were grouped to form a sequential process for coping with Black Swans that aligns with the comparison discussed in Table 1. The rephrased questions, and how they addressed the initial questions, are shown in Table 3.

The sequential order allows a process (as with strategic management) of preparation in addressing Black Swans. In order for an organisation to prepare for the extremes, it needs to know what would be extreme for it. To uncover this, it requires an analysis of the factors that affect it and its environment. The second question can be answered by taking the current strategy/position, matching it to an extreme event, and establishing what the probable outcome would be. The third question should be answered through the outcomes generated by the second questions, while the last question mainly focuses on feedback. It is here that the new strategy should be questioned to test it against the various events conjured up in the first question.

Strategy management has a long list of tools from the work of Sunter [24] to Prahalad and Hamel [13], Mintzberg et al. [18], and Porter [25] & [26].The fact that some of these tools can be used to address the questions listed above forms part of a validation of each of the questions and phases within the framework.

These questions, together with the systems approach to strategic management, have created the platform for the four phases of the ICS framework laid out in the next section.

4 A STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK FOR IMPROBABLE CIRCUMSTANCES

The strategic framework for improbable circumstances focuses not on events that form part of day-to-day operations, but rather on extreme and rare events. For this reason the framework does not seek to replace normal strategic planning for an organization, but rather expands the process.

In order to address the questions in the previous section, the framework is divided into four phases. (Three of the four phases fit into Moll's process synthesis/design phase [14]): the analysis phase, the improbable event creation phase, the fragility analysis phase, and the synthesis phase.) Each phase is described in more detail in the following paragraphs.

It is crucial to note that the role of the framework (and the questions it seeks to answer) is not to look at the implementation or operation (Table 1) of the strategic management process, as this would form part of the existing body of knowledge. The framework, rather, aims to expand on the design (synthesis) of the strategy resulting from the strategic management process, with implementation supporting provided designs for the improbable circumstances.

4.1 The analysis phase

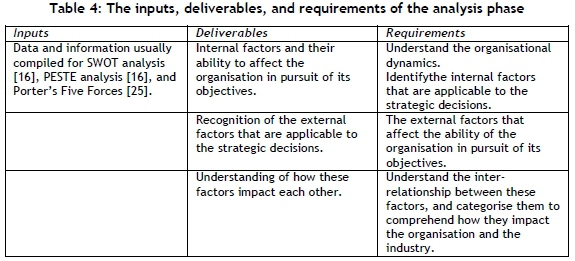

Parallels can be found between this analysis phase and that of strategic management. Through the analysis of the environment and the organisation, factors can be identified that affect the organisation, as well as their outcome on stated objectives and proposed operation. The primary question that needs to be addressed in this phase is:

What has an impact on the success (and possible dowwnfall) of the organisation?

Each phase needs inputs, deliverables, and requirements to operate as a 'checklist' for facilitators or strategic heads to sign-off on before adequately moving on to the next phase (Table 4).

The in-depth knowledge of the internal factors and how they are influenced by the external factors will play a significant role as deliverables in the fragility analysis phase.

4.2 The improbable event creation phase

The improbable event creation phase is necessary to answer the following question:

What circumstances would have an extreme effect on the success (and possible downfall) of the organisation?

In order to improve the deliverables of this phase, the question is split to distinguish between the two extremes, catastrophes and miracles:

1. What circumstances would have a disastrous impact on the organisation?

2. What circumstances would be miraculous for the work of the organisation?

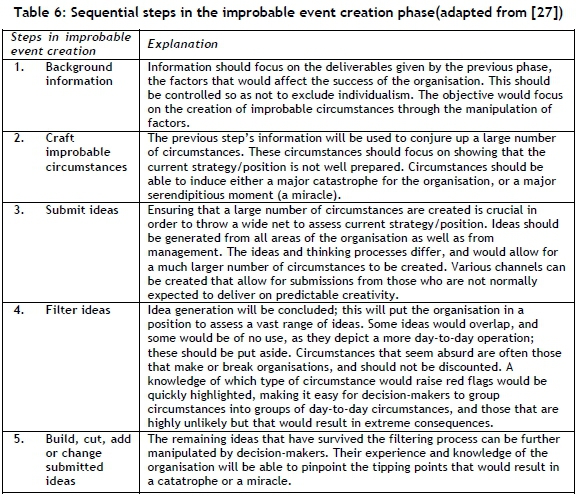

The key to the second question is to ensure that miraculous circumstances are not forgotten because of a constant focus on the worst events; the key is to remember that you can often bet pennies to win dollars (Figure 3). The deliverables of the analysis phase should be communicated to help every person taking part in the strategy design process to understand the organisational and industrial dynamics, as these act as inputs to the improbable event creation phase (Table 5).

Schwartz's [27] process of scenario planning can be highlighted as a tool to validate the phase through by acting as a representative of a tool which would address the requirements. This process has been adapted in order to ensure that the focus is not on just one or two scenarios or on monitoring them.

The circumstances created here are primarily for testing, not for monitoring or forecasting based on current environments. The monitoring of scenarios, as with the normal scenario creation process, would fall within the normal strategic management process of day-to-day strategy formulation.

4.3 The fragility analysis phase

Strategic formulation for the framework asks for an understanding of how certain factors affect an organisation.

"... in order to make a decision you need to focus on the consequences (which you can know) rather than the probability (which you cannot know) as the central idea of uncertainty." - N.N. Taleb (2008) [1]

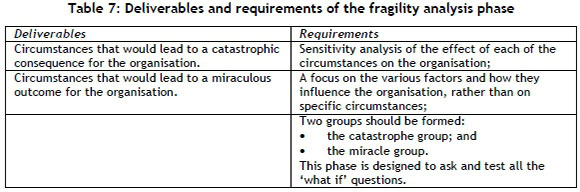

Taleb highlights the errors generally made by focusing on the probabilities and allowing them to dictate actions, rather than on where it should be: on what the outcomes should be, and on the action in reply to these outcomes [6]. The fragility analysis phase is in place to test the consequence/results of the circumstances (as created in the previous phase) on the organisation. Organisations assess the cost of a new investment project and its return on investment (as a function of the probability of success) and, based on these two statements, the decision is made whether to continue with the project or abandon it [28]. The logic of concentrating on the consequence of an event should be the focal point in the assessment of an organisation and its positioning in its environment.

The following question needs to be answered in this phase:

What would the outcome of these circumstances (deliverables from previous phase) on the organisation be?

"Know how to rank beliefs not according to their plausibility but by the harm they may cause." - N.N. Taleb (2008) [1]

The effects of the circumstances on the organisation should be grouped. Certain circumstances would have no major effect; but it is crucial that two groups are formed as a result: the miracles and the catastrophes. Pareto's 80/20 principle should be applied here, as certain scenarios would not have an impact on the workings of the organisation.

These groupings are needed, because a specific solution to groups should be found, rather than addressing only specific single circumstances.

4.4 The synthesis phase

The synthesis phase allows for the creation of the strategy, built on the work done during the previous phases, to create a position within the market to survive/flourish in times of improbable circumstance.

"Don't cross a river if it is four feet deep on average. ... The policies we need to make decisions on should depend far more on the range of possible outcomes than on the expected final number." - N.N. Taleb (2008) [1]

"What matters is not how often you are right, but how large your cumulative errors are." -N.N. Taleb (2008) [1]

The following question needs to be answered in the synthesis phase: How can an organisation prepare for an improbable circumstance?

The ideal solution would be a strategy that prepares for all catastrophe scenarios, as well as one that creates a position to take advantage of opportunities as they are presented by the miraculous events. A rising oil price is seen as an example of a negative event. A logistics company would suffer and, given a large enough rise, it would fail; but oil and petroleum organisations would prosper. The dissimilarity between prospering and struggling depends on perspective and thus position in the market. A logistics company will not easily find itself in a position to prosper in times of high oil prices, but it can highlight it and address how to be prepared for one of the key factors in its industry.

The circumstance groups from the previous phase will be used here to analyse how an organisation can last/thrive in the circumstances that produced either catastrophic or miraculous outcomes. An organisation that does not exist cannot expect to prosper. The first step is thus to focus on survival.

It is impossible to prepare for every circumstance, but being prepared for more than the status quo shows the ability to improve continually. It is in this continuous improvement that the role of industrial engineering is particularly highlighted.

Section 3.1 plays a role in this phase as showing how the organisation can approach the management of these consequences. The crux remains that an organisation needs to show hyper-conservatism when faced with downside risk (catastrophes) and display hyper-aggression when faced with opportunities that cost very little (limited downside risk, the miracle, and applying the 'betting pennies to make pounds' principle) Taleb [1]. Table 8 lists the requirements within the synthesis phase.

"The real importance of the Greeks for the progress of the world is that they discovered the almost incredible secret that speculative reason was itself subject to orderly method...I now state the thesis that the explanation of... active attack on the environment is a three-fold urge: 1) to live, 2) to live well, 3) to live better. In fact the art of life is first to be alive, secondly to be alive in a satisfactory way, and thirdly, to acquire an increase in satisfaction." - Alfred North Whitehead

The synthesis phase includes two sections: 'catastrophe preparation' and 'miracle opportunism'. A third section, Feedback and what we learn by looking back, is added here to take account of the feedback loop that should always play a role in the measurement and monitoring of improved positions. These sections are crucial to the framework, with the first objective - survival - being paramount.

4.4.1 Preparing for the catastrophe

Preparation for catastrophe drives home the point of being hyper-conservative when faced with downside risk. Hyper-conservativism includes positions such as derivatives for hedging, diversifying risk in various markets, insurance, liquid assets, etc.

Diversification strategy has often been used as a tool of risk reduction through the common ownership of businesses, but with individual cash flows that remain the same after exposure (Grant [16]). The cash flows need to be imperfectly correlated, which would allow for the variance of the joint cash flow of the businesses to be less than that of the separate businesses. This phenomenon is how diversification reduces the risk of being dependent on one income stream. Organisations might be slightly less competitive in one industry as resources are being spread, but a strategy of only one core focus has left businesses vulnerable when disaster strikes. The organisations that have 'insured' through the use of diversity are less prone to fail when disaster hits. These organisations have not enjoyed the reduced 'insurance' expenses that other organisations might have, but they are the ones still in operation while those who were uninsured have fallen.

De Neufville listed three basic ways in which to address uncertainty [29]:

1. controlling uncertainty, e.g. demand management;

2. protecting passively, such as building robustness into an organisation; or

3. protecting actively through the creation of flexibility that managers can use to react to uncertainties.

Controlling uncertainty is a way in which to closing off uncertain avenues of the business. If a risk is on of being uncertain as to the demand profile of a company, then this can be managed through signing up various suppliers, and adopting proactive strategies to curtail the uncertainty through formalisation.

Protection of the organisation can come in many forms. Passive protection functions without taking any significant management decisions during operation. Creating redundancy of parts is a standard way of achieving operational robustness in an engineering system.

Protecting actively allows the organisation's decision-makers to take control through specific decisions that alter the organisation.

Strategic decision-making depends a lot on the experience gained from learning. One way of reducing the risk to the organisation is to deploy the experience of executives and veterans in the organisation and industry, applying it to contingency plans (the succession plans).

Great destruction has always left opportunities in its wake. Adequate preparation during times of destruction paves the way to taking advantage of the opportunities to be found when the dust settles. These organisations find themselves operating in an industry when their competitors have been immobilised by the need to make plans to release liquid assets just to survive the aftershock.

An organisation looking to survive and grow would regard it as catastrophic if it were not to pursue opportunities. An organisation should ensure that it is in a position to take advantage of the miraculous event - or that it creates opportunities for itself.

"The greatest enterprise risk may be in not pursuing enterprise opportunities." -Brian E. White, PhD (2007)

"This is a really interesting time because it provides unprecedented opportunities for the survivors." - Hugh Courtney (2008)

4.4.2 In preparation for the miracle

An organisation in the throes of a catastrophe rarely has a clear idea of the risks: it generally just holds on and hopes to survive. The focus on miracles is one in which an organisation might be more aware of the risks involved, especially when it uses capital, as the largest amount to be lost is generally expended capital; and some opportunities are costly if they fail. Executives instinctively magnify the apparent risks and discount their exposure to potential rewards when confronted with rapid change. This tendency has been well documented in the literature of economics [30]. In this case, not displaying hyper-aggression towards opportunities that cost you very little would mean lost opportunities.

The advantage of the times we live in is that organistions can punch much higher than their weight. Technology allows organisations to make considerable consequential impacts through investment capital, even though this seems benign when compared with the investments of a decade ago.

"Today's new digital infrastructure in fact gives relatively small actions and investments an impact disproportionate to their size." - Hagel III et al. (2008) [30]

The quote above shows the investment strategy that Marc Andreessen used at the Andreessen Horowitz venture capital firm. He was catapulted into technology stardom when he co-founded Netscape, which sold to AOL for US$9.6 billion, and Loudcloud, which sold to Hewlett-Packard for US$1.6 billion [31]. Andreessen and Ben Horowitz launched a US$300 million venture capital firm on 6 July 2009. This firm focused on seed capital - an initial investment designed to help start-up ventures to develop. Their aim was to develop 60 to 80 companies using seed capital, with a cash amount of between 75 per cent and 80 per cent, waiting for later-stage investments. The Andreessen Horowitz venture capital firm negates catastrophes by investing in a diverse group of companies, and by positioning themselves to take advantage of opportunities. Their firm had US$22.7 billion under management at the end of January 2014, and remained a growing and going concern (January 2014) [32]. The 10 per cent of start-ups that succeed do it so superbly that they compensate for the 90 per cent that do not - a fact that is explained through the Andreessen Horowitz investment strategy [33].

The key to creating opportunities is new ideas, new inventions, and their management through innovation. Managing the innovation process enables an organisation to take opportunities or to make them. The plaform model used by Apple - a good example of open innovation - created a large number of opportunities for Apple and its users alike. Apple supplies users/developers with a foundation/platform on which they create applications for the iPhone or iPad. The result of this open innovation was the downloading of 1.5 billion applications in the first year of the iPhone's availability. The profit is shared 30/70 between Apple and the user/developer. Apple created cash flow by allowing users to develop applications for themselves [34]. Open innovation creates a way for organisations to reach out to the consumer and to take advantage of their input - and it increases the number of opportunities for the organisation.

The potential rewards are to be had by the groups who take opportunities earlier on, thus explaining the relationship between risk and reward. The example of an equity trading portfolio can explain this. Investing into young, small, unknown organisations is a great risk, giving exposure to risks such as concept risk and execution risk; but the rewards to be gained for this are immense. This is how Andreessen and Horrowitz invest. The risk is large, but the amount of money lost is a known amount, and it can be controlled. As shown by the Andreessen and Horowitz example, investments that need to be exposed to the initial risks in certain industries have been reduced drastically, compared with the preceding decades.

Organisations that fail to take this early risk move into an area where their strategies are reactive to the early risk takers' movements. The contemplative approach of waiting for risks to play out reduces risks, but it also reduces the upside of the rewards with the reduction in these risks. The risk of losing money through 'bets' is immense, but the danger lies in the downside of missing opportunties as competitors move in to reap the rewards of a new market space.

Another example of a strategy that seeks to take advantage of uncontested market space is 'blue ocean strategy' [35]. The focus is on creating an uncontested market space, making the competition irrelevant, creating and capturing new demand, breaking the value/cost trade-off, and aligning the whole system of an organisation's activities in pursuit of differentiation and low cost.

Blue ocean strategy highlights differentiation as a strategy to reduce risk, but also to be exposed to opportunities. Blue ocean strategy is not limited to an industry or organisation, but it is constrained by the strategic move of the organisation. The focus is taken away from the 'red oceans' - the saturated markets and industries - and placed on the opportunities that lie beyond these red oceans. New technology does not create blue oceans: they are created when this technology is linked to what the consumer values.

4.4.3 Feedback and what we learn by looking back

The synthesis of a strategy does not end with the implementation plan to deliver on the new position to be attained. The feedback loop is designed to test the end result of a process in order to assess whether it delivers what it is expected to deliver; and, depending on the asnwer, to adjust in order to increase accuracy and reduce faults.

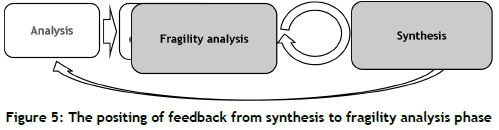

The feedback between the synthesis and the fragility analysis phases will check that the proposed future positioning will not jeopardise the current position by creating one that is exposed to more fragility to improbable circumstance. The fragility analysis needs to be done on the proposed position to ensure that the organisation handles the created improbable scenarios adequately, as a new position could create new risks. Once the strategic minds feel comfortable that the organisation will not become more fragile, the synthesis phase can move into the implementation plan.

you're going to have to make decisions very quickly on fundamental opportunities that may drive your earnings performance for the next decade or more, and you've got to be prepared to make these decisions in real time. That requires a continuous focus on market and competitive intelligence and far more frequent conversations-daily, if necessary-among the top team about the current situation. Senior executives already may be in closer contact because of the emergency they face, but that doesn't necessarily imply that they have the raw material and the structure to work through strategic decisions systematically. These daily conversations have to move beyond getting through that day's crisis to more fundamental strategic issues as well, because the decisions made today may open up or close off opportunities for months and years to come. " - Hugh Courtney (2008)

The more the framework is used, the easier the process will be for the organisation. Organisations will develop an increased awareness of what is required and what needs to be addressed. Some tools have been mentioned in this article; but this is a living framework that allows for various tools to be used within each phase, allowing the organisation to tailor-make the phases for its own use.

Continual use will see an organisation add to the circumstances created, and new tools (for use in the framework) will be the result of a learning organisation. The organisation should aim to work through the ICS framework as often as it works through the general strategic management process to ensure that its aligns and to share new insights across frameworks. It is a constant learning process for the organisation, as continuous interaction is found between the formulation of a strategy, its implementation, and the constant adjustment and revision in the light of increased experience [16]. It is crucial to have a thorough understanding of the factors that affect the organisation, and to what extent they do, as set out in sections 4.1 & 4.3 above.

5 WHAT DO THE EXPERTS THINK?

The validation of a framework is important for ensuring that it is a representation of what could/does happen in reality. Validation through interviews and questionnaires with industry and subject theory experts was chosen as the most practical validation for the study. The constraints on time, as well as the emergence of improbable circumstances, were beyond the control of the author.

Validation was done through five open-ended questions to eight industry and subject matter experts from fields relevant to the study. The objective of every interview was to find the extent to which the interviewees agreed with the research, together with their motivation and recommendations. The questions focused on whether the framework would do that which it was designed to do, the difficulties that would arise in the implementation of the framework, whether the framework adds to the field of strategic management at present, and whether they would apply the framework in their own organisations.

The results of the questionnaire showed that there is a need for a process or tool that addresses how an organisation approaches Black Swans. All the interviewees believed that it was a viable tool, and gave their own recommendations. This outcome is precisely what is required of systems thinking about Black Swans - to use a framework to enable strategic decision-makers to think a certain way and, by enabling this thinking, to apply their own experiences and their own fields of knowledge within the organisation.

The results highlighted that there is a need for a way for organisations to approach Black Swans. They showed that the ICS framework is a viable tool. Seventy-five per cent of the interviewees replied that they would implement the framework in their organization, while the remaining 25 per cent replied that they would need to think further about its implications and requirements before implementation.

6 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The need for the framework was highlighted by the replies from the interviews, which generally stated that, at present, organisations do not have a way to address Black Swan events, whether external or internal.

The ICS framework has been designed to be continually able (on a design level) to adapt; it is thus a living framework, ensuring it is can position itself within each organisation that uses it. The framework, as explained here:

- Is additional/complementary to the current strategic management process, and does not seek to replace it (the wheel has been invented, we just need to improve it);

- Is adaptable; tools that are known to the current strategic heads of the organisation are a good starting point, but more should be added through increased knowledge; and

- should never stagnate, as it should try to reduce the unknown unknowns.

The framework concentrates on risk mitigation and on options creation (through diversification strategies) that are dependent on the consequences it wants to prevent. It is thus paramount that the organisation first looks to survive the catastrophe, and if possible, through diversification strategies, create miraculous outcomes for the organisation.

The framework goes some way to addressing Black Swans, as it plays a part in addressing improbable circumstances. The authors suggest that further research could look at the assessment of an organisation's reaction to these improbable circumstances, and at how it mitigates these highlighted risks/opportunities in the organisation in order to improve its reaction to these improbable circumstances. To continue improving the ICS framework, a definitive understanding is required of how risk management integrates with the ICS framework and management control, and its role in the feedback loop.

The interviews proved that this was a viable tool, with some feedback from the interviews raising interesting thoughts that should be pursued as the framework is enhanced, as well as about the field of study where Black Swans meet strategic management. Areas that might create avenues for further research include:

1. Implementing the framework in organisations to test the time spent per phase, as analysis paralysis will need to be curbed in this framework;

2. From the implementation, understanding the role of innovative thinking in organisations that are used to applying strategic sessions with military precision;

3. Understanding the quality of the role players in each process, and how to get their buy-in for this exercise, which can take time; and

4. A comment that a decentralised business would struggle to implement this framework. A case can be made that decentralised businesses would need to act as stand-alone entities, each running its own framework.

REFERENCES

[1] Taleb, N.N. 2008. The Black Swan: The impact of the highly improbable, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

[2] Schneiderman, R.M., Caulfield, P., Fang, C., Goodridge E. & Bajaj V. 2010. How a market crisis unfolded, New York Times, New York, 20 July 2010. [ Links ]

[3] The Economist. 2002. Telecoms: The great telecoms crash, The Economist, 18 July 2002. [ Links ]

[4] Dye, R., Sibony, O. & Viguerie S.P. 2009. Strategic planning: Three tips for 2009, The McKinsey Quarterly. [ Links ]

[5] Stellenbosch University. 2014. Home of Industrial Engineering, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

[6] Taleb, N.N. 2007. Black swans and the domains of statistics, The American Statistician, 61(3), pp. 198-200. [ Links ]

[7] Porter, M. 1996. What is strategy?, Harvard Business Review,November - December 1996, pp. 61-78. [ Links ]

[8] Grant, R.M. 2006. The knowledge based view of the firm, in The Oxford Handbook of Strategy, D.O. Faulkner and A. Campbell, eds, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 203-229. [ Links ]

[9] Teece, D. 1990. Contributions and impediments of economic analysis to the study of strategic management, in Perspectives on strategic management, New York: Harper Business, pp. 39-80. [ Links ]

[10] Mintzberg, H. 1979. The structuring of organizations, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

[11] Whittington, R. 1993. What is strategy and does it matter?, London: Biddles Ltd. [ Links ]

[12] Meyer, R. & de Wit, B. 2010. Strategy: Process, content, context, Andover, UK: Cengage Learning EMEA. [ Links ]

[13] Prahalad C.K. & Hamel, G. 1996. Competing for the future, Harvard Business Press. [ Links ]

[14] Moll, C.M. 1998. An engineering approach to business transformation, PhD thesis, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

[15] Moll, C.M. & Kruger, P.S. 1998. Using the business engineering approach in the development of a strategic management process for a large corporation: A case study, South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 9(1), pp. 47-65. [ Links ]

[16] Grant, R.M. 2008. Contemporary strategy analysis, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 6th ed. [ Links ]

[17] Pearce, J.A. & Robinson, R.B. 2005. Strategic management: Formulation, implementation and control, McGraw-Hill, New York. [ Links ]

[18] Mintzberg, H., Alstrand, B. & Lampel, J. 2009. Strategic safari: Your complete guide through the wilds of strategic management, New York, Free Press. [ Links ]

[19] Taleb, N.N. & Makridakis, S. 2009. Living in a world with low levels of predictability, International Journal of Forecasting, 25, pp. 840-844. [ Links ]

[20] Tseitlin, A. 2013. The antifragile organization, Communications of the ACM, 56(8), pp. 40-44. [ Links ]

[21] Buttonwood, 2012. Muddled models, The Economist, [Online]. Available: http://www.economist.com/blogs/buttonwood/2012/07/economic-history. [Accessed 14 January 2014]. [ Links ]

[22] Taleb, N.N. & Goldstein, D.G. 2012. The problem is beyond psychology: The real world is more random than regression analyses, International Journal of Forecasting, 28, pp. 715-716. [ Links ]

[23] Taleb, N.N., Goldstein, D.G. & Spitznagel, M.W. 2009. The six mistakes executives make in risk management, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 10, pp. 78-81. [ Links ]

[24] Sunter, C. & Illbury, C. 2001. The mind of a fox: Scenario planning in action, Human & Rousseau, Cape Town. [ Links ]

[25] Porter, M.E. 1987. From competitive advantage to corporate strategy, Harvard Business Review, 65(3), pp. 43-59. [ Links ]

[26] Porter, M.E. 1991. Towards a dynamic theory of strategy, Strategic Management Journal, 12, pp. 95-117. [ Links ]

[27] Schwartz, P. 1991. The art of the long view, Doubleday Business, New York. [ Links ]

[28]Senge, P. 1994. The fifth discipline: The art of the learning organisation, Doubleday Business, New York. [ Links ]

[29] de Neufville, R. 2004. Uncertainty management for engineering systems planning and design, Engineering Systems Monograph (MIT), MITesd, March 29-31 2014. [ Links ]

[30] Hagel III, J., Brown, J.S. & Davison, L. 2008. Shaping strategy in a world of constant disruption, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 10, pg. 81-89. [ Links ]

[31] Maney, K. 2009. Marc Andreessen puts his money where his mouth is, Fortune Magazine, 160(2), pg. 108. [ Links ].

[32] Guglielmo, C. 2012. Andreessen, Horowitz: Venture capital's new bad boys, Forbes, 21 May 2012, [Online] Available: http://www.forbes.com/sites/connieguglielmo/2012/05/02/andreessen-horowitz-venture-capitals-new-bad-boys/. [Accessed April 2012] [ Links ]

[33] Clack, C.D. 2005. Venture analytics, 2005. [Online]. Available: http://www.cs.ucl.ac.uk/staff/CClack/clack/ventureanalytics.htm. [Accessed October 2009]. [ Links ]

[34] Marais, S.J. & Schutte, C.S.L. 2009. The definition and development of open innovation models to assist the innovation process, Conference Article For SAIIE 2009. [ Links ]

[35] Kim, W.C. & Mauborgne, R. 2005. Blue ocean strategy, Harvard: Harvard Business School Press. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author

1 The author was enrolled for a PhD (Industrial Engineering) in the Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Stellenbosch.

2 According to Taleb, fragility is that which does not like volatility, or something that loses operational value after a shock is induced [22].