Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

South African Journal of Industrial Engineering

versión On-line ISSN 2224-7890

versión impresa ISSN 1012-277X

S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. vol.24 no.2 Pretoria ene. 2013

CASE STUDIES

The programme benefits of improving project team communication through a contact centre

T.J. Bond-BarnardI, *, 1; H. SteynII

IGraduate School of Technology Management University of Pretoria, South Africa. tarynjanebond@gmail.com

IIGraduate School of Technology Management University of Pretoria, South Africa. Herman.Steyn@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

A South African national programme to repair government infrastructure uses a contact centre (or call centre) to facilitate and manage communication. An important question is: How does the contact centre benefit the programme and its projects? This study discusses the findings of a survey that quantified the benefits of the programme when the communication between team members in the programme was improved by using a contact centre. The results show that, by using a contact centre to improve the communication between project team members, their perception of communication effectiveness, quality of project deliverables, service delivery, and customer satisfaction of the programme dramatically increases.

OPSOMMING

'n Kontaksentrum word gebruik om kommunikasie in 'n nasionale program vir die herstel van Suid-Afrikaanse Staats infrastruktuur te fasiliteer en bestuur. 'n Belangrike vraag is hoe die program en die projekte binne die program baat by die kontaksentrum. Hierdie artikel bespreek die bevindings van n studie wat die gerealiseerde voordele van die verbetering van tussen-funksie-kommunikasie in die program deur middel van n kontak-sentrum kwantifiseer. Die resultate toon dat, deur die gebruik van 'n kontaksentrum, die projekspan se persepsie van effektiwiteit van kommunikasie, kwaliteit van aflewerbares, dienslewering, en kliënt tevredenheid van die program drasties verbeter.

1. INTRODUCTION

Shao & Müller [1] explain that programmes arise from a need for an effective project governance mechanism that provides a bridge between projects and organisational strategy. The various definitions of 'programme management' have often created confusion. They all stress, however, that programme management is an integrated, structured framework that co-ordinates, aligns, and allocates resources, as well as plans, executes, and manages a set of projects simultaneously. This achieves optimum benefits that would not have been realised had the projects been managed separately [2]. Bartlett [3] sums up the definition nicely by saying that a programme is a collection of vehicles (or projects) for change, designed to achieve a strategic business objective. Similarly, a project is seen as the achievement of a specific objective within a set time frame, involving a series of activities and tasks that consume resources [4].

Programmes have recently become more popular, leading to a tendency in industry and in the project management environment to move from a space of 'projectification' to 'programmification' [5]. However, with the growing popularity of programmes, the challenge of successfully managing these complex multi-project endeavours becomes increasingly difficult [1].

The literature shows that one of the most important and most frequently-mentioned challenges to programme management is that of communication between project team members [3,2,6]. Pinto & Pinto [7] and Pinto & Covin [8] explain that effective communication between team members is very important in a project, as this communication fosters cooperation between the team members, which is so vital to project success.

Communication in a programme or project environment is defined as the transfer of information between the programme or project stakeholders; it involves a person or entity transmitting a message, and another person or entity receiving and successfully understanding the message in response [9]. Cross-functional communication in a programme occurs among a group of people with different functional specialities or multidisciplinary skills, who are responsible for carrying out all the phases of a programme or project from start to finish [10]. For the purposes of this study, 'cross-functional communication' refers to communication between the project team members, rather than to communication between groups of people with different functional specialities.

While frequent formal communication was shown to have no significant effect on the degree of cooperation, Pinto & Pinto [7] show that frequent informal communication (telephone or casual discussions) leads to greater collaboration among the project team members. This 'higher' collaboration between the project team members leads to higher trust levels [11]. Pinto & Pinto [7] ascribe this to the fact that, although 'high trusters' are often willing to confront issues, they are less likely to spend time dealing with the issues. A correlation between frequent communication between team members and project performance [11], as well as between informal communication between team members and project success [7,12,13], is perceived for both high levels of collaboration between the team members and 'high trust' [11,7].

According to Cooke-Davies [14], one of the main reasons why effective communication in a project has such an impact on project performance and the overall success of the programme is 'human success factors'. He explains that it is fast becoming accepted wisdom that it is people who deliver projects, not processes and systems. Nethathe et al. [12] concur that 'people factors' are the most critical factors for multiple project success. Turner & Müller [15] established that the communication needs of project members are best met by a mixture of formal and informal communication, and of written and verbal communication. This research investigates whether a contact centre can provide the kind of effective and frequent communication between the team members that is discussed above, and that is essential for the project to achieve project and programme performance.

'Contact centre' is the name given to a traditional call centre that receives queries and processes and supplies information to an existing or potential client base using a variety of communication channels (SMS, email, social media, etc.), as well as traditional telephonic communication. The contact centre that was studied for this research is the repair and maintenance programme (RAMP) contact centre of the Department of Public Works, which coordinates and manages communication relating to the repair and maintenance activities for all RAMP projects. At the time of the study there were 196 active RAMP projects.

The purpose of the Department of Public Works (DPW) RAMP programme is to alleviate the repair and maintenance backlog at national government facilities. Many of the facilities that fall under the RAMP project are in such a state of disrepair that the facility is rebuilt, with improvements, before the maintenance phase of the project begins. The maintenance component of the project ensures that the facility does not again fall into disrepair. The state-funded programme and contact centre have cost the taxpayer several billion Rands to establish and operate; and so, in the nation's best interests, there is a need to assess the value of the contact centre.

This paper investigates the extent to which the project team members of the 196 RAMP projects perceive project and programme benefits (such as service delivery, customer satisfaction, and quality deliverables) as a direct result of using a centralised contact centre to facilitate and manage all repair, improvement, and breakdown maintenance activities. The influence of the RAMP contact centre on the success factors of stakeholder expectations and requirements, and the performance and quality of deliverables, are also determined; this has a knock-on effect on the perceived project and programme benefits mentioned above. A secondary objective of the study is to determine whether the findings support the call centre-facilitated communication and project performance model that appears in a paper by Bond-Barnard et al. [11]. The following propositions were investigated:

1. The RAMP contact centre effectively manages the communication of breakdowns between the project members;

2. The communication between the RAMP contact centre and the project team members improves the quality of project deliverables;

3. The frequent interaction between the RAMP contact centre and the project team members improves the service delivery of the RAMP programme;

4. Allowing the client's beneficiaries to log calls with the RAMP contact centre improves the programme's customer satisfaction.

A description of the national repair and maintenance programme contact centre and a review of the pertinent literature follow. The paper then describes the research methodology that was used, and how the data was collected. Following this, the results of a survey done on the national repair and maintenance programme and its contact centre are presented, and are then reviewed. The paper concludes with a discussion of the study's findings and with suggestions for further research.

1.1 Background to the RAMP programme

The RAMP programme, initiated in 2001 at a cost of R2 billion a year, was found to be primarily responsible for improving government infrastructure. This finding, as well as many others regarding the current state of government infrastructure, is contained within the South African Institution of Civil Engineering (SAICE) infrastructure report card [16] that analyses and grades the state of engineering infrastructure in South Africa every five years. The scorecard consists of 10 sectors (water, roads, ports, etc.) with 27 subsectors. The 2011 report card graded South African infrastructure as C+ - an improvement from the D- awarded in 2006. The infrastructure report card (IRC) team stated in the 2011 report card that the 2001-2007 repair and maintenance project for South African ports, to the value of R440 million, restored all 12 proclaimed harbours to an excellent condition.

One of the key elements in the success of the programme is the RAMP contact centre. Before the programme began, the DPW decided that all communication about reactive maintenance (or 'breakdowns') at the national facilities would be facilitated, monitored, and managed by a central contact centre. The RAMP contact centre was also given responsibility for documenting the breakdown maintenance activities and performance reporting for all the projects that made up the programme. The RAMP contact centre communicates with the various project teams regularly. A typical project team consists of:

- The client/user department, the DPW, and the user department representatives at the facility;

- The project manager who oversees several projects, usually at different facilities;

- The consulting engineer (consultant) who manages the project on a day-to-day basis and instructs the contractor;

- The contractor responsible for performing maintenance and attending to breakdown repairs at the facility.

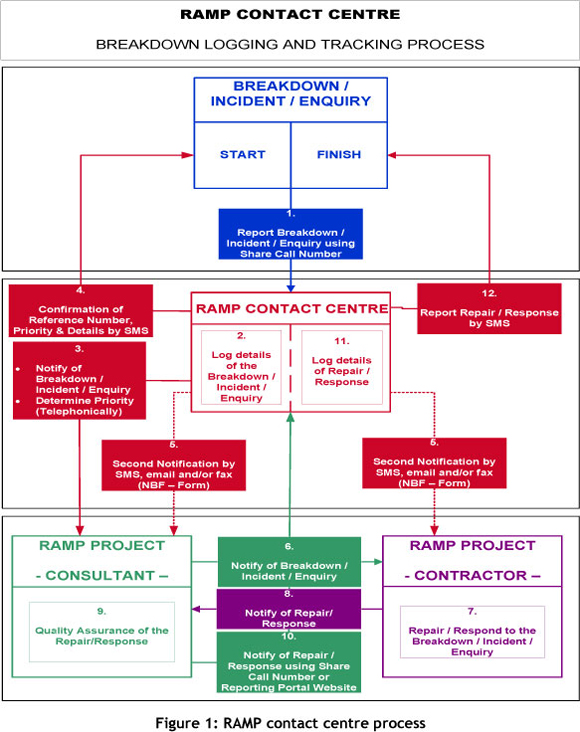

The RAMP contact centre process (see Figure 1) begins when the client at the facility phones, faxes, or emails the contact centre to log a breakdown. This could be anything from an interrupted water supply at a prison to a damaged section of fencing at a border post. The contact centre logs the details of the breakdown and provides the client with a unique reference number. The breakdown is reported to the consulting engineer or project manager, first by telephone (to confirm the priority of the breakdown) and then by fax or email. With the consultant or project manager's consent, a fax is also sent to the contractor. After this, it remains the duty of the consultant to notify the contractor verbally of the breakdown.

Once the contractor has attended to the breakdown, he notifies the consultant. Provided that the consultant is satisfied with the quality of the contractor's repair work or response to the breakdown, the consultant notifies the contact centre by telephone or email that the breakdown has been attended to. The contact centre then follows up the resolved breakdown by contacting the party who originally logged the breakdown, and enquires whether the issue was satisfactorily resolved.

This clearly-defined process for the logging, tracking, reporting, and resolution of project issues forms part of the communication plan for the programme and its projects. The weekly and monthly reports that are distributed to the programme manager and to the 196 project managers indicate each project's performance, and the reports are used as the basis of programme and project progress discussions with the client.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

The RAMP programme and its contact centre, discussed in 1.1, provide the context for this research, which aims to contribute to the programme management body of knowledge by establishing the benefits of using a contact centre to improve communication between team members in a programme and its projects. For this reason, a review of the literature is first provided for programmes and programme management in both an international and a South African context. Thereafter the key contributors to the achievement of benefits in a programme are reviewed, and the characteristics of communication between team members are explained in more detail. Finally, the literature review gives a brief overview of contact centres and programme contact centres.

2.1 Programmes in a South African and international context

Bartlett [3] emphasised that interest in the subject of programmes and programme management has flourished since the publication of the Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency's (CCTA) 'A Guide to Programme Management' in 1994 [17]. He adds, however, that programme management research is still in its infancy, and has yet to catch up with its related discipline, project management.

Programmes and programme management have grown in popularity since the 1990s, when mergers and acquisitions took place on an unprecedented scale, and businesses had to embark on large-scale restructuring following the global recession around that time [3]. Programmes have recently been used as the de facto approach to facilitating whole organisation change. Examples of these are: Year 2000 programmes, preparation for the Euro currency, customer relationship management (CRM) programmes, e-Commerce programmes, mergers and acquisitions, enterprise resource management (ERM) programmes; and in South Africa, preparation for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. However, Bartlett [3] is of the opinion that programme management will have to become a much more sophisticated discipline to tackle the complexities of the accelerated large-scale business change that is yet to come.

Programmes have become the instrument of choice for government service delivery and policy implementation. The popularity of programmes in government stems from the fact that they are an effective way to coordinate the project efforts of various government departments in order to achieve a synergy of benefits. This would not have been realised had the projects been managed separately [18,2]. The national RAMP programme is no different; the facilities of 12 national government departments (Agriculture, Arts and Culture, Land Affairs, Border Control Ports of Entry, Correctional Services, Defence, Home Affairs, Public Works, Justice, Labour, Police Services, and all government elevator installations) are included in the RAMP programme. The strategic business objective of this programme is to eradicate the backlog in facilities and infrastructure repair and maintenance for all these government departments. Some of the potential benefits that the DPW foresaw at the implementation of the programme -with its centralised contact centre - were better performance management (especially in the quality of deliverables), more effective programme communication and information management, and improved service delivery and customer satisfaction.

2.2 Programme benefits

Programme benefits can be accrued throughout the life of a programme, and are crucial to attaining programme success [3]. Bartlett [3] states that programme benefits are:

- the success criteria measurements of cost, time, and quality;

- programme design changes;

- performance and quality of deliverables; and

- stakeholder expectations and requirements.

Yet the realisation of programme benefits is rarely given the attention it deserves (either in practice or in the literature): it is rarely properly understood or undertaken [14,3]. According to Bartlett [3], benefits are a perception of what might be achievable, and need to be properly quantified before they can progress from being mere requirements. The measure of benefit success is acceptance by the project client or stakeholders that their expectations have been articulated. However, success, like quality, is a perception. A programme must, therefore, establish measurable success criteria for its deliverable elements. It is not enough only to specify the achievable benefits and their success criteria. Several actions that will occur during the life of a programme will affect the nature and quality of the desired benefits [3], which de Wit [19] calls success factors.

The literature states that many of the things that can go wrong with the benefits in a programme have to do with expectations of management [20,21,22,5,23,24,19]. Thus this paper primarily discusses how the RAMP contact centre influenced stakeholder expectations and requirements, and the performance and quality of the deliverables' success factors, which have a knock-on effect on the stated programme benefits of service delivery, customer satisfaction, and quality deliverables.

The programme success factors of communication effectiveness, service delivery, customer satisfaction, and quality deliverables were chosen because they could be evaluated by all members of the 196 project teams (including the clients or beneficiaries); this provided better insight for the topic of this paper. The quantification of project members' perception of programme benefit achievement was used as the success criteria.

2.3 Communication between team members

The literature states that communication between team members is an essential project success factor that plays a role in determining stakeholder expectations and the performance and quality of project deliverables, which are key success factors for the achievement of project and programme benefits [3,25]. Effective communication is about exchanging meaningful information between groups of people with the aim of influencing beliefs or actions [2]. Furthermore, timely and effective communication between teams and across organisational boundaries - termed cross-functional communication - is essential to programme or project management performance and success [11,26,7].

According to Belout & Gauvreau [26], Pinto & Pinto [7], and Scott-Young & Samson [27], communication between team members is also one of the most frequently studied project team success factors. After all, it is communication between team members that best addresses stakeholder expectations and requirements; and it is communication in the project team that is responsible for the successful delivery of project deliverables according to predetermined quality parameters; and in the end the result is customer or client satisfaction. Yet a contact centre's role in facilitating communication between the team members in a project and a programme has not yet been investigated.

One may ask, "Why is communication so important for programme success?" The Office of Government Commerce (OGC) in [2] states that communication is critical in any change process. Moreover, the greater the change, the greater the need for clear communication about the reasons and rationale for the change, the expected benefits, the plans implemented, and its proposed effects [2]. Likewise, programme management is aimed at exchanging timely and useful information between and among the stakeholders and project team. Bartlett [3], Blomquist & Müller [28], CCTA in Shehu & Akintoye [2], and Williams & Parr [6] concur that a lack of communication between team members is a major challenge to programme management. It is clear from the literature that a lack of communication between team members can lead to the late delivery of a project, which will in turn affect the timely delivery of a programme (OGC in [2]).

2.4 The history of contact centres

'Contact centres' is the name given to traditional call centres that receive queries or information from, and process and supply information to, an existing or potential client base using a variety of communication channels such as telephone, fax, letter, SMS, email and, increasingly, instant messaging. Various companies and departments including finance, legal, IT, insurance, marketing, and sales make use of contact centres with great success as an integral part of the enterprise's overall CRM.

Contact centres have experienced significant growth and popularity since the advent of the first automatic call distributor (ACD) in the mid-1960s. This growth was spurred on by the technological advances in the late 1970s and the 1980s that made call centres indispensable to businesses [28]. In the 1990s, the number of call centres continued to grow as a result of the rise of the internet. During this time websites became the central point of contact and sales for an ever-increasing number of companies, and call centres were essential in dealing with customer service and technical support [29]. Contact centres have now replaced the traditional telephonic call centre, as they manage all client contact for companies through a variety of channels such as telephone, fax, letter, email and, increasingly, on-line live chat or instant messaging [30].

Although the literature frequently refers to contact centres, there appears to be very little information about the use of contact centres in projects and programmes [11]. If contact centres have proved to be so indispensable for CRM in organisations, why have programme and project managers not shown an interest in using contact centres to attend to aspects of project and programme stakeholder relationship management and project team coordination? This paper aims to educate programme and project management practitioners on the benefits of using a contact centre for programme communication in particular.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research examines the extent to which the programme's project team members perceived programme benefits - such as communication effectiveness, service delivery, customer satisfaction, and quality of deliverables - because a contact centre facilitated some of the communication between them. The impact of the contact centre on the effectiveness of the team's communication is investigated. The literature states that it is this communication that has been shown to influence programme or project performance and success. These benefits are presented as four propositions that are described in the introduction and tested in this paper.

The predominant appreciation that people have of their own perceptions of a phenomenon (e.g. the programme benefits of improving cross-functional communication in a project using a contact centre) necessitated a research design that provides the opportunity to gather and interpret user perceptions in a programme context. A survey - a quantitative research method - was therefore chosen.

This research focuses on the RAMP contact centre users, and on how they communicate with the contact centre and within their project team. The scenarios of the theoretical model as presented in and by the propositions in 1 were used to develop a set of statements that concentrated on users' perceptions of the RAMP contact centre's contribution to the attainment of different project 'benefits'. Iterative review and refinement resulted in three group-specific questionnaires with about 30 questions each for the client, contractor, and project manager participants. Four of the questions measured the users' perceptions of the contact centre in facilitating and managing project team communication to achieve the stated project benefits of project service delivery, customer satisfaction, and quality. Questions were formulated in the first person to give users the opportunity to reflect on their personal experience or perception. Likert-type scales were used to express the participants' degree of agreement with the statements made. The questionnaire was validated through a process of discussions and pre-tests that focused on question application and clarity. Six users assisted with verifying the validity of the questions during the pre-tests, and a few minor enhancements were made. The pre-tests indicated that the questionnaire was unambiguous, and that it could be completed in less than 10 minutes. An explanatory letter or email was sent to all the participants; the questionnaire was distributed by sending an email with a website link to some of the participants, and by sending others the survey by fax or email.

3.1 Issues of measurement

The RAMP programme referred to in this research consists of numerous projects, each with a project manager and a contractor. The research population consisted of the project managers and contractors associated with the 196 active projects registered on the programme contact centre database. Including 'client', these three designations were considered as the units of analysis for the investigation. Furthermore, the project manager and contractor populations associated with the 196 active projects registered with the contact centre served as the sample frame. Census sampling was specifically selected for the project manager and contractor populations because the authors had access to these two populations, whereas convenient sampling was used for the client group because it had an unknown population. (This is discussed in more detail below.)

The sub-population for the project manager and contractor groups was reduced to unique samples only; some participants were involved in more than one project, and it was decided not to swamp or overwhelm these participants with surveys that might cause them to decide not to answer at all. Consequently, the project manager and contractor populations were determined to be 194 and 134 respectively. The survey was distributed to the entire project manager and contractor population. Convenient sampling was employed for the client group, as the size of the sub-population was unknown, it was cost-effective, and the study had severe time constraints.

3.2 Data collection

Research data was provided by 73 project managers, 22 contractors, and 22 clients who completed the questionnaire. The low response rate for the surveys was due to non-response error and time constraints. The non-response error was caused by the inability of the researcher to gain participation from potential respondents. It is presumed that this was caused by some respondents lacking the time to participate. However, the responses received gave a good indication of the predominant perceptions of the various groups. Incompleteness caused the rejection of 14 of the project manager and 10 of the contractor questionnaires, resulting in 59 and 12 usable questionnaires respectively. No incomplete questionnaires were received for the client group.

The 59 project manager and 12 contractor questionnaires were completed on-line using Survey Monkey, whereas the 22 clients completed their questionnaires in hard copy and returned them either by email or by fax. The online survey results were exported into Excel from Survey Monkey, while the email and fax surveys were manually captured into the same Excel spread sheet, which was then checked for integrity.

The overall study was limited owing to a low response rate and time constraints, and because the participants were self-selected. Other limitations were that the RAMP contact centre only facilitates and manages the breakdown portion of communication in each project.

4. RESULTS

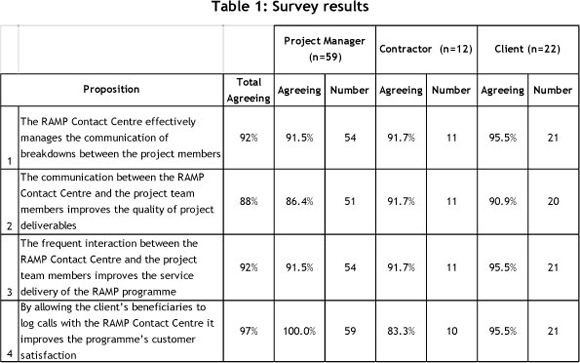

The 93 useable questionnaire responses were entered into spread sheets to enable the calculation of the number of occurrences of each of the agreement options (strongly agree, partially agree, neither agree nor disagree, partially disagree, and strongly disagree). The results are presented in Table 1 according to the four propositions used to structure the questionnaire. The results are interpreted and discussed in the next sub-section.

4.1 RAMP contact centre effectiveness

Eighty-six (93 per cent) of the participants were of the opinion that the RAMP contact centre effectively manages the communication of breakdowns between the various members of the project team: the project manager, the contractor and the client or beneficiary. However, three (two project managers and one contractor), or three per cent of the participants, perceived the contact centre as being ineffective in managing breakdowns in communication in the project team. A further four participants - three project managers and one contractor - stated that they neither agreed nor disagreed that the contact centre was effective in managing communication breakdowns between the members of the project team. This sufficiently supports the proposition that the RAMP contact centre effectively manages the communication of breakdowns between project members. The null hypothesis of the proposition was therefore rejected.

4.2 Perceived quality of project deliverables

The perception that a higher frequency of communication between the RAMP contact centre and project team members improved the quality of project deliverables was noted by 82 (88 per cent) of the participants. What was interesting was that none of the contractors (the team members who actually carry out the project work) disagreed with this statement. This could mean that they derive the most benefit from the frequent contact centre communication, as it assists them to do work that adheres to the project manager's specifications and that meets the client's expectations. In total, only one project manager and one client partially disagreed with this statement of association. Nine participants neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement. A majority of 88 per cent of the 93 survey participants supported the second proposition that communication between the RAMP contact centre and the project team members improves the quality of project deliverables.

4.3 Perceived service delivery outcomes

The majority of the participants, 86 (93 per cent), perceived that a higher frequency of interaction between the RAMP contact centre and the project team members improved the service delivery of the repair and maintenance programme, whereas two participants (two per cent) disagreed with this statement. Five participants (five per cent) neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement.

It was interesting to note again that none of the contractors disagreed that a higher frequency of interaction between the RAMP contact centre and the project team members improved the service delivery of the repair and maintenance programme. This is in line with the results for quality of project deliverables mentioned above, as service delivery is seen as the act or manner in which an article in public demand is supplied, and that is also appropriate to its purpose (including functional and quality infrastructure, buildings, water supply, and sewage removal systems) [31]. As 93 per cent of the programme participants agreed that frequent interaction between the RAMP contact centre and the project team members improves the service delivery of the RAMP programme, it can be concluded that this proposition was correct.

4.4 Customer satisfaction

The most significant finding of the survey was that 90 participants (97 per cent) agreed that allowing clients or beneficiaries to log calls with the RAMP contact centre improves the programme's customer satisfaction. Seventy-three participants (79 per cent), made up of 46 project managers (78 per cent of stratum), eight contractors (67 per cent of stratum), and 19 clients (86 per cent of stratum), totally agreed with this statement. Two participants (two per cent) neither agreed nor disagreed, and one contractor (one per cent) totally disagreed with the statement. The fact that 97 per cent of the participants agreed that allowing the client's beneficiaries to log calls with the RAMP contact centre improves the programme's customer satisfaction, supports the proposition. There was no significant difference in response between the three groups; this provides additional validation for this proposition.

The customer satisfaction findings suggest that the RAMP contact centre is most successful in keeping the programme's clients and beneficiaries happy by providing them with a 24/7 contact centre that is able to capture, report, and follow-up on reported or queried breakdowns. This can be attributed to the fact that they receive information immediately, and the breakdown is repaired quickly as there is a formalised communication and resolution process in place in the project. In the end, a programme or project is not a success unless it is perceived to be a success by those who originally commissioned it - the clients or beneficiaries. This proposition, together with propositions one and three, also supports the model developed by Bond-Barnard et al. [11]. Both this model and Turner & Müller [15] state that frequent communication indirectly influences project performance.

5. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The results show that when the contact centre is used in the RAMP programme to facilitate and manage communication between team members in the projects, several benefits are realised. The study also determines the value that the RAMP contact centre adds to the programme. This finding validates the national expenditure for the programme and ensures its continued support. Support for the call centre-facilitated communication and project performance model [11] is also obtained from this study.

Most notably in the case of RAMP, customer satisfaction is perceived to improve, as it provides the numerous clients and beneficiaries of the programme immediate access to communicate their breakdowns to the rest of the project team by making use of a central contact point - in this instance, the RAMP contact centre. By using the communication breakdown and other regular reporting functionalities of the contact centre, the project team's communication improves. The project team perceives the contact centre to be effective in its task of managing communication breakdown between them, and in assisting them to improve the quality of project deliverables. This is done by keeping the client informed about progress and by keeping a channel of communication with the project team open, should a project issue occur.

Other benefits that occur as a direct result of improved communication between the team members are that the quality of project deliverables improves because of the communication between the contact centre and the project manager, the contractor, and the client. The improved quality of deliverables also influences the level of service delivery perceived and experienced by members of the project team, especially the clients. The majority (93 per cent) of the programme participants perceived that service delivery improves due to frequent interaction between the RAMP contact centre and project team members. In conclusion, the RAMP contact centre improves the communication between team members in the project, as well as the project team's perception of the quality of project deliverables, service delivery, and customer satisfaction.

Future research possibilities might include investigating the programme benefits associated with a contact centre that facilitates or manages the bulk of the communication in a programme; or establishing the specific project benefits of improving communication between team members.

REFERENCES

[1] Shao, J. & Muller, R. 2011. The development of constructs of program context and program success: A qualitative study, International Journal of Project Management, 29(8), pp. 947-959. [ Links ]

[2] Shehu, Z. & Akintoye, A. 2010. Major challenges to the successful implementation and practice of programme management in the construction environment: A critical analysis, International Journal of Project Management, 28(1), pp. 26-39. [ Links ]

[3] Bartlett, J. 2002. Managing programmes of business change, 3rd edition. Project Manager Today, Hampshire. [ Links ]

[4] Munns, A.K. & Bjeirmi, B.F. 1996. The role of project management in achieving project success, International Journal of Project Management, 14(2), pp. 81-87. [ Links ]

[5] Maylor, H., Brady, T., Cooke-Davies, T. & Hodgson, D. 2006. From projectification to programmification, International Journal of Project Management, 24(8), pp. 663-674. [ Links ]

[6] Williams, D. & Parr, T. 2006. Enterprise programme management: Delivering value, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. [ Links ]

[7] Pinto, M.B. & Pinto, J.K. 1990. Project team communication and cross-functional cooperation in new program development, Product Innovation and Management, 7, pp. 200-212. [ Links ]

[8] Pinto, J.K. & Covin, J.G. 1989. Critical factors in project implementation: A comparison of construction and R & D projects, Technovation, 9, pp. 49-62. [ Links ]

[9] Torrington, D. & Hall, L. 1998. Human resource management, 4th edition, Prentice Hall, London. [ Links ]

[10] BusinessDictionary.com, 2012. What are cross-functional teams? Definition and meaning, WebFinance Inc.: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/cross-functional-teams.html [Accessed: 24-Jan-2012]. [ Links ]

[11] Bond-Barnard, T.J., Steyn, H. & Fabris-Rotelli, I. 2013. The impact of a call centre on communication in a programme and its projects, International Journal of Project Management, 31 (7), pp. 1006-1016. [ Links ]

[12] Nethathe, J.M., van Waveren, C.C. & Chan, K.-Y. 2011. Extended critical success factor model for management of multiple projects: An empirical view from Transnet in South Africa, South African Journal of Industrial Engineering, 22(2), pp. 189-203. [ Links ]

[13] Pinto, J.K., Slevin, D.P. & English, B. 2009. Trust in projects: An empirical assessment of owner/contractor relationships, International Journal of Project Management, 27(6), pp. 638-648. [ Links ]

[14] Cooke-Davies, T. 2002. The 'real' success factors on projects, International Journal of Project Management, 20, pp. 185-190. [ Links ]

[15] Turner, J.R., & Müller, R. 2004. Communication and co-operation on projects between the project owner as principal and the project manager as agent, International Journal of Project Management, 22(3), pp. 327-336. [ Links ]

[16] SAICE. 2011. SAICE Infrastructure Report Card for South Africa, The South African Institution of Civil Engineering, Midrand.

[17] CCTA. 1994. A guide to programme management, CCTA. [ Links ]

[18] De Coning, C. & Günther, S. 2009. Programme management as a vehicle for integrated service delivery in the South African public sector, Africanus, 39(2), pp. 44-53. [ Links ]

[19] De Wit, A. 1988. Measurement of project success, International Journal of Project Management, 6(3), pp. 164-170. [ Links ]

[20] Yang, L.-R., Chen, J.-H. & Wang, H.-W. 2011. Assessing impacts of information technology on project success through knowledge management practice, Automation in Construction, pp. 1-10. [ Links ]

[21] Maylor, H., Geraldi, J.G. & Johnson, M. 2010. I can't get no... satisfaction: Moving on from the dominant approaches to managing quality in complex programs, Project Management Institute, pp. 1-23. [ Links ]

[22] Kloppenborg, T.J., Tesch, D. & Chinta, R. 2010. Demographic determinants of project success behaviours, Project Management Institute, pp. 1-11. [ Links ]

[23] Maylor, H. & Johnson, M. 2010. It's not my fault! Exploring the role of the client in program performance, Project Management Institute, pp. 1-17. [ Links ]

[24] Fortune, J. & White, D. 2006. Framing of project critical success factors by a systems model, International Journal of Project Management, 24(1), pp. 53-65. [ Links ]

[25] Lehmann, V. 2009. Communication and project management: Seeds for a new conceptual approach, In: Proceedings ASAC (Administrative Sciences Association of Canada), pp. 1-18. [ Links ]

[26] Belout, A. & Gauvreau, C. 2004. Factors influencing project success: The impact of human resource management, International Journal of Project Management, 22(1), pp. 1-11. [ Links ]

[27] Scott-Young, C. & Samson, D. 2008. Project success and project team management: Evidence from capital projects in the process industries, Journal of Operations Management, 26(6), pp. 749-766. [ Links ]

[28] Blomquist, T. & Müller, R. 2006. Practices, roles, and responsibilities of middle managers in program and portfolio management, Project Management Journal, 37(1), pp. 52-66. [ Links ]

[29] Pearce, J. 2011. The history of the call centre, Callcentrehelper.com: http://www.callcentrehelper.com/the-history-of-the-call-centre-15085.htm [Accessed: 24-Jan-2011]. [ Links ]

[30] EWA Bespoke Communications, 2010. Contact Centre vs. Communication Centre vs. Call Centre - but which one is right?, EWA Bespoke Communications: http://ewa-ltd.blogspot.com/2010/03/contact-centre-vs-communication-centre.html [Accessed: 24-Jan-2012]. [ Links ]

[31] Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2012. Merriam-Webster dictionary, Merriam-Webster, http://www.merriam-webster.com/ [Accessed: 28-Feb-2012]. [ Links ]

* Corresponding author

1 The author was enrolled for an M Eng (Project Management) degree in the Graduate School of Technology Management, University of Pretoria.