Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versión On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versión impresa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.67 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/67-1-1012

BIGGER PICTURE LINGUISTICS

Linguistic dualities: Deconstructible or defensible?

Bertus van Rooy

Faculty of Humanities, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands | UPSET Research Focus Area, North-West University, South Africa. E-mail: a.j.vanrooy@uva.nl

At least since Saussure, the idea that language can be understood through a number of dualities has been a defining trope of linguistic theorising. In structuralist approaches (in the broadest sense, including functional interpretations and other formalist approaches), pairs of concepts are used to make sense of the discipline and of the resources that languages make available to users for communication. Key dualities proposed by Saussure (1959[1916]) include synchronic and diachronic, system (langue) and utterance (parole), syntagmatic and associative, and signifier and signified. Some of these contrasts have been taken up by the Prague school of Structuralism; for instance, Jakobson (1956) refined the contrast of syntagmatic and associative into syntagmatic and paradigmatic, while extending the syntagmatic to metonymy and the paradigmatic to metaphor as modes of meaning creation. Chomsky (1965) offers a mentalist interpretation of the system/utterance contrast in his differentiation of competence from performance. More recently, Otheguy et al. (2015) also rely on a strict duality of the mental and social aspects of language, arguing for translanguaging as a better conceptualisation of the mental grammar and limiting the notion of "named languages" to the social and political domain beyond the purview of linguistics proper.

However, several dualities have been targeted for criticism or rejection. Langacker (1987) argues against the rule/list fallacy that separates regular and exceptional linguistic patterns, while in a similar vein, Halliday (1985) argues for grammar and the lexicon to form a continuum rather than a dichotomy. Linguists from a construction grammar (Croft 2001) or emergentist (Bybee 2006) perspective argue against a grammar/usage, or analogously competence/ performance or langue/parole contrast. For many of these scholars, a gradient view of linguistic organisation is preferred to a strictly dichotomous view.

A very different challenge to the conceptual approach associated with pairs of binary concepts comes from Derrida, who highlights the blind spots engendered by oppositional pairs, particularly regarding the extent to which one term in a pair is given a privileged status. In his commentary on Saussure, Derrida (1974[1967]) focuses on the opposition between speech and writing, and in doing so, engages with the entire conceptual approach of Saussure. In Derrida's reading, Saussure privileges the spoken as the true essence of language above the written, which is derived from the implicit assumption that the spoken word is able to make the meaning of linguistic signs present. This concern with 'presence' as the source of meaning is shown to be premised on a shortcut, where the fact that a speaker is present and articulates the words is taken as guarantee of the meaning. At the same time, Derrida shows that Saussure also defines meaning as purely differential, one word means what it does through contrast to the next word, and the next one: a chain which defers the moment of fixing the meaning of a word infinitely. Derrida coins the term différance for this, combining the meanings of "differ" and "defer" in one strategic concept.

The question that these challenges raise is whether linguistics will continue to derive value from the use of dualities, binary concept pairs. By way of a partial and speculative answer, I want to propose that a better appreciation of the kinds of binary pairs, together with a richer notion of the functions of language and the possibility of simultaneity rather than complementarity in at least some of the concept pairs, may yet serve to rescue some pairs of concepts and provide fruitful, if forever provisional, understanding of linguistics as a discipline and language as an object of investigation. My proposal is that a contrast can be drawn between the following sets of binary pairs:

1. Pairs that pick out different relation types within language, such as syntagmatic/ paradigmatic, linear/hierarchical or collocation/contrast.

2. Pairs that oppose observable and invisible enabling concepts, such as parole/language, utterance/system, or performance/competence.

As a subset of these, or maybe partially different set, there is also a third contrast:

3. Pairs that pick out an idealisation (typically static or constant) from a messy reality (often dynamic and variable), such as standard/dialect or synchronic/diachronic.

Functional concepts are often not binary, although there is a sense in which language is often understood to have two overarching functions, each going by different names. Halliday (1985) calls them the "ideational" and "interpersonal function", while Givón (1993) talks about the mental representation of experience and its communication to others. However, Halliday (1985) offers a third function as fully equivalent to the first two, which he calls the "textual" function. Givón lists several other functions, textual included, although he affords them a secondary status.

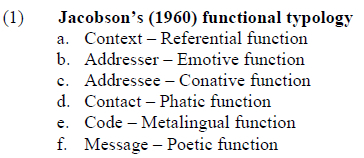

An older functional typology is offered by Jakobson (1960), who proposes a model of communication with six elements, each having its own function. The addresser sends a message to the addressee. To be operative, the message requires a context (the "referent" in another, somewhat ambiguous, nomenclature), which must be able to be grasped by the addressee and must either be verbal or be capable of being verbalized; a code fully, or at least partially, common to both the addresser and addressee (or in other words, to the encoder and decoder of the message); and, finally, a contact, a physical channel and psychological connection between the addresser and the addressee, enabling both of them to enter and stay in communication. A summary of the six functions that focus on each one of these six elements are listed in (1).

Jakobson argues for the primacy of the referential function in language, talking about reality. He argues, however, that one or some of the other functions may be dominant in a particular context, although most of the time, several functions are performed simultaneously. Jakobson, thus, does not yet give high status to the interactive (interpersonal/communicative) function (as Givón and Halliday do), but sees the six elements as being separate.

A rather important subsequent insight that reinforces the non-primacy of the referential (ideational/representation) function comes from the work of Tomasello (1999, 2008) on the cultural origins of human cognition and communication. He argues that the collaboration between humans as the precondition for many subsequent advances distinguished humans from the higher primates. Tomasello (2008) speculates that human language may have started in the gestural rather than oral mode at its point of evolutionary origin, and served the function of coordinating behaviour with others, rather than representing mental concepts at first.

A crucial insight from Tomasello's work, which Givón develops along slightly different lines, is that these key functions of language initially developed separately and later combined, both in the long-term development of language in human society and in the individual process of language acquisition of a present-day child. This perspective should be combined with one further crucial insight that was not available to Saussure, Derrida and various others who thought seriously about the dualities that help to understand language: language need not be construed as a container for meaning, but can alternatively be seen indexically, as something that activates a response in the addressee, without fully encoding a meaning or determining a response. Derrida developed an idea that moves in this direction in his engagement with the speech act theory of Austen (in Margins of Philosophy, but for this summary, I rely on Culler [1983]). Derrida argues that, though both context and conventional meaning of utterances contribute to the meaning, since context is unstable and infinitely extendible, the specific meaning of a specific utterance can never be fully determined or fixed. This is consistent with Derrida's notion of 'différance', but gives more specific concepts with which to work. Culler (1983) takes the point further by arguing that, because of these conditions, meaning is not entirely free in an "anything-goes" sense. However, the interactive dimension is still not salient in Derrida's work, which is where the proposal for simultaneous functions in language offers a fresh perspective on utterance meaning. Halliday and Givón, very explicitly, argue for the simultaneous performing of both the representational and communicative function, and that their joint effect (together with the textual for Halliday) shapes the selection and combination of words in an utterance. The binary pair representational-communicative therefore does not form an opposition, but rather offers a simultaneous-if independently motivated-force that gives language both meaning and purpose.

***

This notion of simultaneity applies to the entire first set of concept pairs identified earlier. Relations in language are simultaneously in operation. When formulating an utterance, a speaker has to select and combine words, which collocate with certain words, while contrasting with alternative selections and combinations. Word combinations obviously display linear structure, but this is not contradictory to hierarchical structuring, even if most constructionalists tend to assume much shallower structure and much more local structure than the much more involved hierarchical structure of an X-bar tree. Therefore, complementary pairs of relations in language that can be present simultaneously are certainly still valuable in making sense of how words (or elements more generally) combine in language to form meaningful utterances.

For some of the pairs that pick out an idealisation, there is also a clear simultaneous relationship. A subset of these concern the messy gradient reality and the constant that can be discovered in these forms. A classic example is the phoneme as the constant behind the continuous stream of speech sounds. To Saussure, there is a necessary boundary between these, with the linguistic system becoming completely divorced from the concrete shape that sound has in reality. Later work by Jakobson partially overcame this gulf by postulating the importance of phonetics for understanding phonology, hence of the material reality of sound for the phonological organisation thereof.

The same can potentially be said of other forms of patterning in language: humans make categorisation judgements on the observable, material occurrences that we call communication, taking a particular instance as an instance of something that can also be recognised in other contexts. The much more interesting question perhaps regards the nature of that relationship: how do the concrete, individual events (utterances, parole, if you like) relate to the constants that are identified across instances? Here, two camps can be identified: aprioristic and emergent. If the instances are interpretable on the basis of an a priori system, one is confronted by the chicken-and-egg-problem of how the system of constants came about in the first place in order to enable the understanding of the variable instances - where did the first chicken come from, in order to lay the next egg? If an emergentist view is adopted, the question becomes how instances are used as basis for generalisation in the absence of some kind of system into which to incorporate the new categorisation judgement - that is, where did the first egg come from, from which the chicken was hatched? A gradualist approach is possible here, much like the conceptual shift required in evolutionary biology. One should not ask how the mature, complex, contemporary organisms emerge from the first primitive single-cell organisms, without understanding that small incremental steps over an unimaginably long period of time form the bridge between them. Thus, both the potentially primitive utterances of the first communicators and the potentially equally primitive first generalisations of human communication are linked to contemporary language through a very long series of connections of a very incremental kind. The linguist is in a weaker position than the evolutionary biologist in that the evidence about these many intervening steps cannot be accessed in the way that biologists do have some fossil records and other kinds of material evidence from which inferences can be drawn and models be derived.

An important insight that points to the possibility of a rather flexible, but therefore less debilitating reliance on the system for producing or understanding utterances, is the work pointing to the number of "prefabs", or prefabricated language. Sinclair (1991) formulated this as the tension in language between the idiom principle and the open principle. In construction grammar, this relates to the degree of schematisation in grammatical representations as well as the degree of entrenchment. some utterances do not rely on a very general pattern for the understanding - how-do-you-do, howzit, hoe-gaan-dit, hoesit, hoe-lykit all suffice as conventional greetings in English and Afrikaans, with various degrees of cross-linguistic influence possible and happening in the south African context. one might analyse the various interrogative patterns in these sentences as instantiations of the abstract schema of the interrogative. However, the typical user does not rely on that but simply stores these word combinations as complete units, entrenched as separate units even though they conform to a general abstract schema, too. Yet, creative tweaking of these formulas remains possible, showing that, should access be required, the syntactic patterns encoded by the more general schemas can be recovered and used. This is best understood as cases of Kahneman's (2011) two modes of thinking, "fast" and "slow". When required, speakers can also engage with the linguistic patterns enabling particular compositions - i.e., slow thinking/"open principle", but very often, they rely on partially assembled words with predictable functions - i.e., fast thinking /"idiom principle".

There need not be a contradiction or a need for choice - it may be that language production and understanding are not reliant on Occam's razor. Evidence that children rely on such much more concrete patterns comes from the work on the limited range of verbs and predictable situations that were uncovered by Tomasello (1992) and his collaborators over several decades, upon which general schematic patterns are abstracted incrementally and over a period of time. Further supporting evidence comes from the overextensions or illicit generalisations of children and adult second language learners, that is, when they use words beyond the contexts of their conventional usage to capture a wider generalisation of a different case for which they do not yet have other conventionalised resources. These illicit generalisations also show subtle differences - when extended to different cases (e.g. a child using a term like "dog" to refer to a different quadruped domestic animal, such as a "cat"), the extension is of a much more concrete kind (B resembles my expectation of A sufficiently to be regarded as another instance of the category I call A), as opposed to a generalisation based on a deeper abstraction (such as the regularisation of the English past tense in "go - goed" or "lead - leaded", where the notion of a past tense, a less concrete category, is required to guide the creative extension).

***

There remains a subset of idealisations where there is a stronger value judgement implied, such as language/dialect, or standard/variant. In these cases, the constant behind the variable and gradient reality is not so much a constant that human categorisation spontaneously creates and relies on, but rather one that is artificially coined, where powerful users generalise their usage to the status of norm and start to judge the deviations of others as being not "different" but rather "deficient" in respect of the norm (=themselves). It is not "unnatural" to observe difference and to maximise correspondence with others; in the development of new varieties of English, it has been shown very clearly that humans tend to align with others (Trudgill 2004). This is not peculiar to new varieties of English, either; people use language to align with others, as is known from work on covert prestige, the diffusion of slang, and ultimately, language change in general. The issue arises when the process of alignment between people - the social function of language beyond mere communicative exchange, which Labov (2010) identifies as key driver of language change - is overlooked and interpreted as if it were a threat to communicative exchange.

At the same time, however, one should not extrapolate from the politicisation of the prestige variant to deny the social reality of language itself. One such a case is the position developed by Otheguy et al. (2015) against "named languages" in favour of their view that "translanguaging" is the only mental reality in the individual mind - individuals, in other words, merely have idiolects, which consists of all the linguistic resources that they command, irrespective of the possible association of the resources with named languages such as English or Afrikaans. They draw a sharp boundary between the sociopolitical reality in which named languages as constructs make sense, and the internal, psychological reality of idiolects where distinctions between languages have no role to play. They criticise linguists and other members of society for blending the two opposing poles - the individual's internal and the external sociopolitical realities. They define translanguaging as "using one's linguistic repertoire, without regard for socially and politically defined language labels or boundaries" (Otheguy et al. 2015:297). They add that individuals in actual contexts of use are mindful of both the social judgements of others and the extent to which a particular choice from their full repertoire would be understood. However, they do not generalise such "mindfulness" to the possibility that the use of language, with the intent to be understood and to interact, has enduring effects on the mental grammars themselves, rather than mere filtering effects in order to seek social approval when required. Furthermore, they do not consider the reinforcing effect of frequency of use on mental representation (Bybee 2006) or the probability (if not fact) that language usage that proves successful in achieving the communicative purposes is more likely to be used again -the competition and selection aspect of evolutionary models of language change (cf. Croft 2000; Mufwene 2002).

A less oppositional view of the way the internal and external (or individual and social) jointly contribute to the shaping of the mental grammars of individuals will yield a different insight. It will respect the valid political critique raised by Otheguy et al. (2015), that the linguistic competence of an individual cannot be grasped reliably (e.g. in testing contexts) or engaged fully (in leaning contexts) by reducing it to one part that corresponds to a standard language only. On the other hand, it will not deny the unmistakable social effects on the internal mental grammars - not artificial impositions but inherent effects. In a surprising manner, those taking a translanguaging approach along the lines developed by Otheguy et al. (2015) have a similar view of the strict social/mental opposition adhered to by Chomsky (1965). "Linguistic conventions" (rules, vocabulary items, constructions, etc.) are not unstructured and occasional, but form interlocking subsystems, be they called "mental grammars" or "constructional networks". Similarly, the term "language", including that subset that corresponds in denotation to "named languages", is a useful way of thinking about the fact that human languaging is not an unpredictable mix of bits and pieces, but tends towards regularity. This is not an imposed regularity, or only an imposed regularity, but also an inevitable outcome of the attempt to communicate successfully.

***

In sum, dualities are useful constructs in language, but not in a logical or algebraic form that requires strict exclusion. Many dualities are linked by gradience between them, or are simultaneously present, rather than constituting strict alternatives. An argument against dualities in language should, however, not be premised on those that are open to be co-opted in the workings of power, open to political manipulation, as if all such attempts at understanding the functioning of normal language are of necessity a regressive political project aimed at maintaining existing networks of exploitation. However, as Otheguy et al. (2015) point out, this distinction is not always easy to draw. That shouldn't be a reason for not trying, though.

References

Bybee, Joan. 2006. From usage to grammar: The mind's response to repetition. Language 82(4), 711-733. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2006.0186 [ Links ]

Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.21236/AD0616323 [ Links ]

Croft, William. 2000. Explaining Language Change: An Evolutionary Approach. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Croft, William. 2001. Radical Construction Grammar: Syntactic Theory in Typological Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198299554.001.0001 [ Links ]

Culler, Jonathan. 1983. On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism after Structuralism. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.2307/3684109 [ Links ]

Derrida, Jacques. 1974 [1967]. Linguistics and grammatology. [Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.] SubStance 4(10), 127-181. https://doi.org/10.2307/3683950 [ Links ]

Derrida, Jacques. 1982 [1972]. Margins of Philosophy. [Translated by Alan Bass.] Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Givón, Talmy. 1993. English Grammar: A Function-based Introduction, Volume 1. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.engram2 [ Links ]

Halliday, Michael A.K. 1985. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Edward Arnold. [ Links ]

Jakobson, Roman. 1956. Two aspects of language and two types of aphasic disturbances. In Fundamentals of Language, 69-96. The Hague: Mouton.

Jakobson, Roman. 1960. Linguistics and poetics. In Robert E. Innis (Ed.) 1985. Semiotics: an Introductory Anthology, 145-175. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [ Links ]

Labov, William. 2010. Principles of Linguistic Change, Volume 3: Cognitive and Cultural Factors. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444327496 [ Links ]

Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar, Volume 1: Theoretical Prerequisites. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Mufwene, Salikoko S. 2001. The Ecology of Language Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511612862 [ Links ]

Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia Garcia & Wallis Reid. 2015. Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review 6(3), 281-307. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0014 [ Links ]

Saussure, Ferdinand de. 1959 [1916]. Course in General Linguistics. [Translated by Wade Baskin.] New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Sinclair, John McH. 1991. Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford: Oxford University press. [ Links ]

Tomasello, Michael. 1992. First Verbs: A Case Study of Early Grammatical Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511527678 [ Links ]

Tomasello, Michael. 1999. The Cultural origins of Human Cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674044371 [ Links ]

Tomasello, Michael. 2008. Origins of Human Communication. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/7551.001.0001 [ Links ]