Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus (SPiL Plus)

versión On-line ISSN 2224-3380

versión impresa ISSN 1726-541X

SPiL plus (Online) vol.67 Stellenbosch 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.5842/67-1-1011

BIGGER PICTURE LINGUISTICS

The intersection of syntax and poetry in the first Hebrew acrostic poem of Lamentations

Jacobus A. NaudéI; Cynthia L. Miller-NaudéII

IDepartment of Hebrew, University of the Free State, South Africa E-mail: naudej@ufs.ac.za

IIDepartment of Hebrew, University of the Free State, South Africa. E-mail: millercl@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Acrostic poems in Biblical Hebrew are structured both by the successive letters of the Hebrew alphabet at the beginning of successive strophes as well as by the ordinary features of poetic style. In this essay we consider how these two aspects of poetic style interact with the poet's syntactic choices in the first poem of the Book of Lamentations (1:1-11) in order to determine to what extent the poetic constraints have hampered or warped the syntactic structures employed in the poetic lines or half-lines.

Keywords: alphabetic acrostic; poetic style; syntax; Biblical Hebrew; parallelism

1. Introduction

Among the books of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, the Book of Lamentations is unique as the only book that is entirely in poetic form without any prose element. By contrast, although prophetic oracles are usually framed as poetry, each prophetic book contains a brief prose introduction indicating the reception of God's message by the prophet and sometimes situating the prophecy within a historical context (e.g., Isa 1:1; Jer 1:1; Ezek 1:1; Hos 1:1, etc.). The book of Psalms has brief prose sentences marking the ends of internal divisions (41:14 at the end of Book 1; 72:20 at the end of Book 2; 89:53 at the end of Book 3; 106:48 at the end of Book 4) in addition to the so-called "psalm titles" providing metatextual information at the beginning of some psalms including attribution, type of musical composition, musical accompaniment, historical circumstances, and liturgical uses (e.g., Psalm 3:1; 4:1, etc.). Proverbs has both a prose introduction (1:1) and prose introductions to various collections of proverbs within it (11:1; 25:1; 30:1; 31:1). But even though Lamentations is entirely poetry, we will argue below that its syntactic structures are essentially like those in prose; there are not two separate Hebrew grammars in the Bible - one for prose and another for poetry.

Lamentations consists of five separate poems, each exhibiting the same overall pattern of twenty-two strophes (or, groups of lines), a number based on the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet (see Dobbs-Allsopp 2015: 170-173). In the first, second and fourth poems, each of the twenty-two strophes begins with the successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet. The third poem exhibits twenty-two strophes of three lines each, where the first word in each of the three lines begins with the same letter of the alphabet. The fifth poem has twenty-two strophes but does not follow the alphabetic acrostic pattern.

This structural pattern at the beginning of lines, which is called an acrostic or more specifically an alphabetic acrostic, presents an additional constraint on the poet's use of the Biblical Hebrew language. Scholars work with the assumption that the ancient Hebrew poets stretched or strained normal language usage to compose poetic acrostics, because the first word of some lines had to be forced into a macrostructural mould. Therefore, the assumption has been that the phonological structure exhibits not only control over the overall shape of the poem, but also over the syntax (for example, word order) used in the poem, which has been described as "highly artificial nature" (Watson 1984: 191) and as written "primarily for aesthetic reasons" (Soll 1988: 322). We will re-examine these claims below. Nonetheless, the advantage of the alphabetic acrostic for the study of Biblical Hebrew poetry is, as Lowth observed long ago, that the alphabetic acrostics mark and define poetic lines so exactly that it is impossible to mistake them for prose; instead, the alphabetic acrostic style reveals the structural reality of the poetic line (Lowth 1835: 28-29). The alphabetic acrostics thus provide an ideal corpus for the examination of the syntax of poetic lines.

The poems in Lamentations also exhibit parallelism, a prominent feature of Biblical Hebrew poetry.2 Parallelisms relate to poetic lines, which we analyse in Lamentations as consisting of a first half-line, a short pause, a second half-line, and a longer pause.3 Parallelism as a largely semantic phenomenon involving correspondences between lines or half-lines may also manifest itself structurally on the phonological, lexical, morphological or syntactic levels (Berlin 1985). In this essay, we advance our broader research agenda of describing the syntactic features of Biblical Hebrew, in general, and of Biblical Hebrew poetry, in particular. Our concern is to further explore to what extent the poet's concern with producing the acrostic structure may have affected the syntax of the poem, in general, and the word order of the individual lines, in particular. In other words, in the process of producing the macrostructural feature of acrostic style, did the poet alter or re-shape the local structure of the lines to fit the overriding concern for acrostic style? Or, as suggested by Gordis (1974: 124), is the poet's skill able to "transcend" the "self-imposed literary form" of the acrostic? In a previous study exploring this question, we analysed the third acrostic poem (Lamentations 3), which exhibits the most tightly structured acrostic in Lamentations with three successive verses (each verse itself a poetic line) beginning with the same letter of the alphabet (Miller-Naudé & Naudé 2022). We were particularly interested in the word order of the first half-line of the line since its first word contributes to the acrostic macrostructure. Our conclusion in that study was that acrostic style relates to a macrostructural feature, but it does not necessarily constrain or affect the internal shape or syntactic structure of the lines. In this essay we explore in detail whether the syntactic structure of the three lines of each of the first eleven strophes (first part) of the first poem, a total of 33 lines, is influenced by the parallelistic style, as well as the acrostic mould of the poem, with the result that the syntax of these lines differs significantly from that found in prose.

The essay is structured as follows: In section 2, we identify those grammatical items which must obligatorily occur in initial position and determine their distribution in the strophes of the poem under investigation. Section 3 checks the representation of items which usually appear in sentence-initial position as well as other unmarked cases, while Section 4 investigates syntactically and pragmatically marked word order. Section 5 discusses the cases of so-called unusual or difficult word order.

2. Items obligatorily in initial position

We begin with grammatical forms which must obligatorily occur in sentence-initial position, whether independent or embedded.

As described in Biblical Hebrew grammars (Van der Merwe, Naudé & Kroeze 2017: 477; Waltke & O'Connor 1990: 328-329) the WH- or content question word 'êká ('how') functions as an exclamation to introduce the nature of a particular state of affairs or events, in this case a lament - 'How she sits alone!' (1:1ai). It occurs in sentence-initial position in the first (1:1ai), second (2:1ai) and fourth poem (4:1ai and 4:2bi) of Lamentations, the same position that it has in other examples of exclamations (Isa 1:21, Jer 48:17, 2 Sam 1:19), as well as in direct questions (Deut 12:30), indirect questions (Jer 36:17) and rhetorical questions (Deut 1:12, Exod 6:30, Gen 26:9).

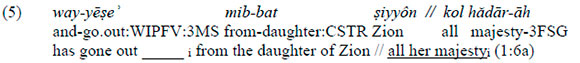

In selecting words to begin the w- strophe, Hebrew poetics faced a particular challenge. Lexemes beginning with the letter w- are extremely rare in Hebrew as a result of a phonological shift in early Northwest Semitic in which word-initial w- became y- (Blau 2010: 103). This sound change removed all w-initial verbal roots from Hebrew. A very few nouns are attested with word-initial w-; these "have to be regarded as having come into Hebrew after this shift had ceased to operate" (Blau 2010: 103).4 The ubiquitous clitic conjunction w- ('and'), however, did not participate in the sound change (see the explanation in Blau 2010: 103 that w- was originally joined as an enclitic to the preceding word) and thus provided a solution for the poets. Furthermore, the so-called wayyiqtol verbal form (a past tense form which begins with a historical form of the conjunction w-) must absolutely occur in sentence-initial position (Van der Merwe, Naudé & Kroeze 2017:188-194) and this form was frequently used by the acrostic poets for the w- strophe. In our poem, the wayyiqtol form occurs at the beginning of 1:6a -wayyësë 'it went out' ('From daughter Zion all her majesty went out'). The wayyiqtol verbal form introduces the w- line elsewhere in the acrostic poems in Lamentations (2:6ai, 3:16ai, 3:17ai, 3:18ai and 4:6ai). In our poem, a number of these wayyiqtol verbal forms also occur in initial position in other lines, where they are not required by the acrostic structure (1:6ci, 1:8cii, 1:9bi).

Some conjunctions occur only in sentence-initial position, especially subordinating conjunctions, which conjoin a dependent sentence to a matrix sentence. In our poem, the subordinating conjunction ki ('that, because') occurs prominently in sentence-initial position (1:5b, 1:8bii, 1:9cii, 1:10, 11cii) (Van der Merwe, Naudé & Kroeze 2017: 432-436).

When the prepositional clitic l- ('to') introduces an infinitive construct that is the predicate of an embedded sentence dependent upon a finite matrix verb, the preposition occurs at the beginning of the dependent sentence, as occurs in 1:11bii (Van der Merwe, Naudé & Kroeze 2017:174). In prose, an infinitival clause introduced with the preposition ordinarily occurs after the matrix verb, but either order is possible (Gesenius, Kautzsch & Cowley 1910: 348).

In all of the examples in this section, the local syntax of the sentence is completely normal. The poet has exploited grammatical forms which must appear in sentence-initial position for use at the beginning of the line or half-line as part of the macrostructure of the acrostic pattern.

3. Usual or unmarked sentence word order

We now identify those lines which have usual or unmarked sentence word order. In these lines, the grammatical constituent or form at the beginning of the line usually (but not obligatorily) appears at the beginning of a sentence.

In ten cases, a qatal (perfective) verbal form is in initial position (1:1bi; 1:2cii; 1:3a; 1:5ai; 1:6bi; 1:7ai; 1:7di; 1:7dii; 1:10bii; 1:11bi).

In one instance, a cognate infinitive absolute precedes the finite verb (yiqtol) and occurs in initial position in the line, namely 1:2ai: 'Bitterly she weeps in the night' (lit. weeping she weeps in the night). As noted by the grammars, the usual order for a cognate infinitive absolute is to precede rather than to follow the finite verb (Van der Merwe, Naudé & Kroeze 2017: 177-184).5

Verbless (or, nominal) sentences also display ordinary sentence word order.6 The subject is followed by a predicative adjective (1:4a) or a predicative prepositional phrase (1:2aii, 1:9ai). When the participle functions as the predicate, the word order is also subject-predicate (1:4b (2x) and 1:4ci; 1:11ai).

The indicative negative marker lö ('not') precedes the verb when its scope of negation is the sentence, as in 1:3bii. The negative existential marker ên takes as its scope of negation a participle that follows it without an overt subject constituent (see Miller-Naudé & Naudé 2015), as illustrated by1:7cii ('and there is no helper for her') and 1:9bii ('there is no comforter for her'). The sentence in 1:2b is similar except that the prepositional phrase läh ('to/for her') is topicalised before the participle ('for her there is no comforter among all of her lovers').

In 1:8ci the particle gam ('also, even') occurs at the beginning of the sentence (and line) before an independent subject pronoun. Although gam alone does not necessarily occur in sentence-initial position, a sense of the range of flexibility in the placement of gam can be obtained by observing where it occurs elsewhere in Lamentations: in 4:3 at the beginning of a line (and sentence) before a noun phrase subject; in 4:21 at the beginning of a sentence (and half-line) before a prepositional phrase. In 4:15, it occurs in the middle of a sentence (and line) preceding a finite verb. The combination of gam followed by the subordinate conjunction ki ('that') in 3:8 always occurs in sentence-initial position in the Hebrew Bible (Miller-Naudé & Naudé 2022).

What we have seen in this section is that the ordinary or unmarked word order is followed both with verbal sentences and with verbless sentences.

4. Lines with syntactically and pragmatically marked word order

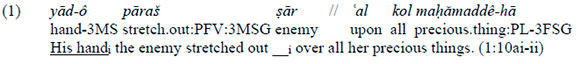

We now turn to lines (or half-lines) that exhibit syntactically and pragmatically marked word order in that a non-verbal constituent occurs at the beginning of the sentence. The first syntactic construction is topicalisation in which a non-verbal constituent is moved to the beginning of the sentence within the sentence boundary (1:1c; 1:2ci; 1:3c; 1:5aii; 1:5b; 1:5c; 1:8ai; 1:8aii; 1:8bi; 1:10a). In (1), the object is topicalised.

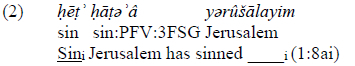

It could be argued that topicalisation serves the acrostic format, placing a word that begins with y- at the beginning of a verse. However, the acrostic style cannot be the motivation in cases where the sentence with topicalisation does not occur at the beginning of a verse (e.g. 1:1c; 1:2ci; 1:3c; 1:5b; 1:5c; 1:8aii; 1:8bi). In one line, given in (2), where topicalisation occurs at the beginning of the verse, the unmarked sentence without topicalisation would begin with the verb hatd á ('she sinned') which begins with the same letter (h-) as the topicalised noun het ('sin'); topicalisation cannot, therefore, be attributed to acrostic style in this case.7

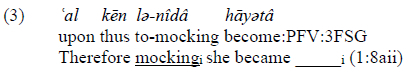

The subject is topicalised in eight cases (1:1c; 1:2ci; 1:3c; 1:5aii; 1:5b; 1:5c; 1:8bi; 1:10a).8 In two half-lines (1:3bi, 1:8ci) an independent personal pronoun fulfils the role as a topic subject with a qatal (perfective) verb form, which is a null subject verb form. A prepositional phrase may also be topicalised, as in (3).

The topicalised prepositional phrase ('to mocking') is not the object of the intransitive verb, but rather an adjunct.

Topicalisation is a normal syntactic configuration involving a non-verbal constituent in initial position in a sentence (see Naudé 1990; Miller-Naudé & Naudé 2019; Naudé & Miller-Naudé 2017; Miller-Naudé & Naudé 2021). The topicalised constituent may function pragmatically as either the topic of the sentence (i.e., it serves to orient the sentence in terms of information structure) or as the focus of the sentence (i.e., it serves to contrast the constituent with other explicit or implicit alternatives) (see Holmstedt 2009, 2014). In every case of topicalisation within our poem, the usual pragmatic effects seem to be at work. There is therefore nothing unusual about these syntactically and pragmatically marked constructions.

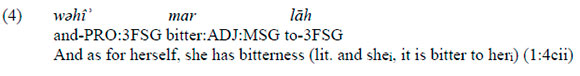

Left dislocation is a syntactic construction that is distinct from topicalisation in that the left dislocated element occurs outside of the left edge of the sentence boundary and a resumptive element occurs within the matrix sentence (see Naudé 1990; Miller-Naudé & Naudé 2019; Naudé & Miller-Naudé 2017; Miller-Naudé & Naudé 2021). Left dislocation is thus syntactically distinct from topicalisation, although it is like topicalisation in that it also involves marked word order. There is one instance of left dislocation in our corpus, given in (4).

The dislocated constituent is the third person feminine singular independent pronoun,9 which is resumed with a pronominal clitic that is the object of a preposition; the construction is that of hanging topic left dislocation (Miller-Naudé & Naudé 2021). The matrix clause is a verbless clause with an adjective (mar 'bitter')10 and the prepositional phrase (läh 'to her'), which is an idiom for expressing possession.11

5. Unusual or problematic word order patterns

We now turn to lines or half-lines with unusual or problematic word order patterns.12Extraposition, a construction in which a constituent is moved to the end of the sentence, occurs three times, illustrated in (5).

Because the verb is in the wayyiqtol form, a conjugation that requires the verb to be in sentence-initial position (as mentioned above), the normal position for the subject would be immediately after the verb. Instead, the subject is extraposed to the end of the sentence after the adjunct (prepositional phrase).13

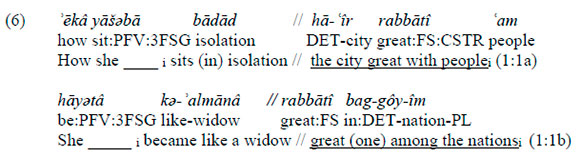

In the first two lines of the poem, each consisting of a sentence, the subjects are extraposed to the ends of their respective sentences. Poetically, the extraposed subject comprises the half-line of each line, seen in (6).

In the first line (1:1a), the extraposed subject consists of a definite noun ('the city') followed by an adjective ('great') in construct with another noun ('people'); the relation between these two NPs is ambiguous - either they are in apposition ('the city, that is, the great one of people' meaning 'the city that is full of people') or there is an unmarked relative clause ('the city (which is) full of people'). The extraposed subject in the second line (1:1b) is poetically parallel to the one in the preceding line - the word rabbäti('great') is repeated and the word góyim ('nations') is parallel to the collective am ('people'). The syntax is again problematic, since an adjective followed by a PP is not an NP. There are two possibilities. One possibility is that rabbäti is a headless unmarked relative ('the one who is great among the nations'). A second possibility is that the DP 'the city' from the previous line should be understood as implicit or elided from the previous line ('[the city] (which is) great among the nations') (see Miller 2008). However, like topicalisation, extraposition is a normal syntactic construction in Biblical Hebrew (see Miller-Naudé and Naudé 2019); the syntactically problematic aspects of extraposition highlighted here relate to the internal phrasal structure of the extraposed constituents.

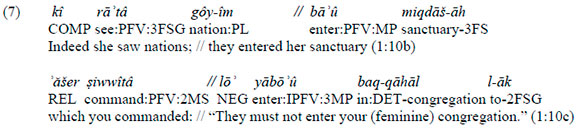

In one instance, given in (7), there is an extraposed relative clause and determining its head is problematic.

The relative clause is extraposed because its head cannot be the preceding prepositional phrase. As noted, ascertaining the head of the relative clause is problematic; there are three syntactic options.14 First, if góyim ('nations') is the head of the relative clause, it cannot be the object of the command. In such a situation, Hebrew could use a resumptive element within the relative clause to make clear that the nations are not the individuals commanded (e.g. the prepositional phrase alêhem 'concerning them' could be added to the sentence - rätägôyim... aser siwwitá 'alêhem 'she saw the nationsi ... which you commanded concerning themi'), but resumption is optional and there are several similar prose examples without resumption.15 A second option is to understand the relative as relating generally to the preceding sentence/line: the nations entering Israel's sanctuary was something that God had commanded Israel must not happen. Rarely in the Hebrew Bible can an entire sentence serve as the head of a relative (Holmstedt 2016: 113).16 A third option is to understand the relative as having the subject clitic pronoun of the finite verb rätä ('she saw') as the head. Holmstedt (2016: 109) argues that clitic pronouns in Biblical Hebrew can rarely serve as the head of a relative clause when the clitic pronoun is the nearest possible antecedent. The examples that he cites are primarily possessive clitic pronouns or object clitic pronouns.17 It is therefore unlikely that a subject clitic pronoun that is not the nearest antecedent, as in this strophe, would serve as the head of the relative.

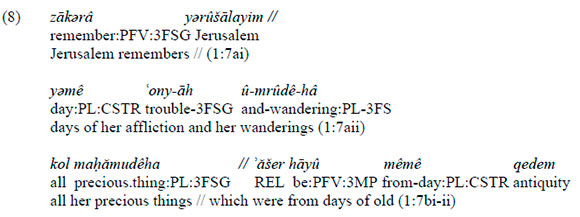

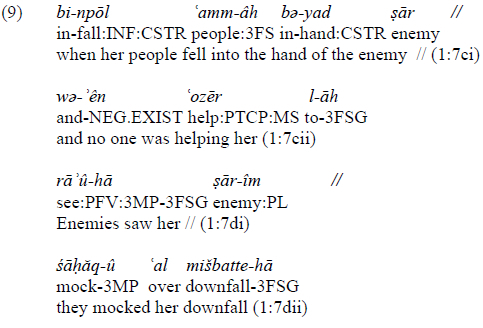

Lamentations 1:7 is the longest strophe in the poem with four lines rather than three, and it is the only strophe in which sentences extend beyond single poetic lines, viz. both 1:7a-b and 1:7c-d comprise sentences. Both sentences have problematic syntactic aspects.

In the first sentence (1:7a-b), given in (8), identifying the object of the main verb zäkdrä ('she remembers') is problematic.

In 1:7a-b, the relationship of the noun phrase in 1:7aii to the remainder of the sentence is unclear. At first glance, it appears to be the object of the verb zãkdrâ ('she remembered') in the first half-line (1:7ai). However, the poems in Lamentations continuously consider the past a pleasant time and the present a time of affliction and wanderings; therefore, this noun phrase is often considered an adverbial noun phrase that provides the time frame for the remembering rather than the object of the verb (i.e. what is remembered).

The second sentence (1:7c-d), given in (9), exhibits intricate syntactic embedding. First, it is the only instance in our poem of syntactic embedding in the form of an infinitive construct as the object of a preposition (1:7ci), a construction that is common in prose, but far less common in poetry. It also has a circumstantial clause with a negative existential predicate (1:7cii). The matrix sentence is in 1:7d; in no other verse in the poem does the matrix sentence occur with two dependent sentences (in the form of poetic half-lines) preceding it.

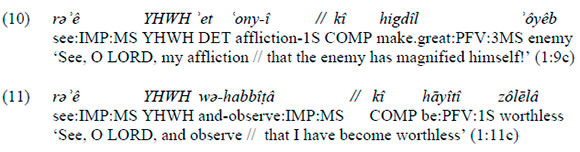

In two lines (1:9c; 1:11c), given in (10) and (11), direct speech quotations are unframed, that is, they occur without being introduced by a quotative frame.

In Biblical Hebrew prose, direct speech quotations are almost always introduced with a quotative frame (Miller 2003[1996]: 210-226); however, in poetry it is not unusual for direct speech quotations to be entirely unframed (O'Connor 1980: 409-414).

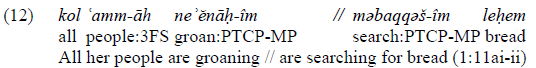

Finally, in 1:11a, given in (12), each half-line of the line has a predicative participle, but only the first half-line has an explicit subject.

In Biblical Hebrew, the participle, unlike the finite verb forms, does not index a subject - an explicit subject is usually required, except in cases where it is preceded by the mirative particle hinnê ('behold') (see Naudé & Miller-Naudé 2023: 27-28; Joüon & Muraoka 2006: §154c; Waltke & O'Connor 1990: §37.6a; on the mirative characteristics of hinnê, see Miller-Naudé and Van der Merwe 2011). Rarely, however, the subject of a predicative participle may be omitted, when it can be retrieved from the immediately preceding context.18

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, an analysis of the thirty-three lines of our poem (Lamentations 1:1-11) has demonstrated that the poet utilised a wide variety of syntactic constructions within the structural frameworks of an alphabetic acrostic and poetic parallelism. However, in no sense was the poem "artificial" (Watson 1984) or syntactically "defamiliarised" (Lunn 2005). Instead, the poet has used a wide range of syntactic structures as resources for composing a powerful opening lament for the destruction of the city of Jerusalem. Often the poet uses less common syntactic constructions for condensing the information into the poetic line or half-line -omission of subjects that can be retrieved from context, covert rather than overt relative clause markers, noun phrases whose role in the larger sentence as object or adjunct are unspecified and must be inferred by the hearer or reader, the head of an extraposed relative clause whose referent is ambiguous (or perhaps multivalent), and direct speech that appears abruptly without a quotative frame to orient the reader to a change of deictic perspective. These features both compact the lines (and half-lines) of the poem while simultaneously expanding its interpretive possibilities.

Acknowledgements

This work is based on research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Jacobus A. Naudé UID 85902 and Cynthia L. Miller-Naudé UID 95926). The grantholders acknowledge that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF supported research are those of the authors, and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.

References

Alter, Robert. 1985. The Art of Biblical Poetry. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Berlin, Adele. 1985. The Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Biblia Hebraica Quinta. 2004. Fascicle 18: General Introduction and Megilloth. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft.

Blau, Joshua. 2010. Phonology and Morphology of Biblical Hebrew. Linguistic Studies in Ancient West Semitic 2. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781575066011 [ Links ]

Collins, Terence. 1978. Line-Forms in Biblical Poetry. A Grammatical Approach to the Stylistic Study of the Hebrew Prophets. Rome: Biblical Institute Press. [ Links ]

Cross, Frank Moore. 1983. Studies in the Structure of Hebrew Verse: The Prosody of Lamentations 1: 1-22. In Carol L. Meyers & Michael Patrick O'Connor (eds.) The Word of the Lord Shall Go Forth. Essays in Honor of David Noel Freedman in Celebration of His Sixtieth Birthday, 129-155. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Dobbs-Allsopp, F.W. 2001a. The Enjambing Line in Lamentations: A Taxonomy (Part 1). Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 113: 219-239. https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.113.2.219 [ Links ]

Dobbs-Allsopp, F.W. 2001a. The Effects of Enjambment in Lamentations (Part 2). Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 113: 370-385. https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.2001.003 [ Links ]

Dobbs-Allsopp, F.W. 2015. On Biblical Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199766901.001.0001 [ Links ]

Freedman, David Noel & Erich A. von Fange. 1996. Metrics in Hebrew Poetry: The Book of Lamentations Revisited. Concordia Theological Quarterly 60(4): 279-305. [ Links ]

Gesenius, Wilhelm, Emil Kautzsch & Arthur Ernest Cowley. 1910. Gesenius' Hebrew Grammar. 2nd English edition. Oxford: Clarendon. [ Links ]

Gordis, Robert. 1974. The Song of Songs and Lamentations: A Study, Modern Translation and Commentary. Revised and augmented edition. New York: Ktav. [ Links ]

Greenstein, Edward L. 1983. How Does Parallelism Mean? In A Sense of Text: The Art of Language in the Study of Biblical Literature, 41-70. A Jewish Quarterly Review Supplement. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Grosser, Emmylou J. 2021. What Symmetry Can Do That Parallelism Can't: Line Perception and Poetic Effects in the Song of Deborah (Judges 5:2-31). Vetus Testamentum 71: 175-204. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685330-12341455 [ Links ]

Hillers, Delbert R. 1974. Observations on Syntax and Meter in Lamentations. In Howard N. Bream, Ralph D. Heim & Carey A. Moore (eds.). A Light unto My Path: Old Testament Studies in Honor of Jacob M. Meyers, 265-270. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [ Links ]

Holmstedt, Robert D. 2009. Word Order and Information Structure in Ruth and Jonah: A Generative Typological Analysis. Journal of Semitic Studies 54(1): 111-39. https://doi.org/10.1093/jss/fgn042 [ Links ]

Holmstedt, Robert D. 2014. Critical at the Margins: Edge Constituents in Biblical Hebrew. KUSATU 17: 109-56. [ Links ]

Holmstedt, Robert D. 2016. The Relative Clause in Biblical Hebrew. Linguistic Studies in Ancient West Semitic, 10. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781575064208 [ Links ]

Holmstedt, Robert D. 2019. Hebrew Poetry and the Appositive Style: Parallelism, Requiescat in pace. Vetus Testamentum 69: 617-648. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685330-12341379 [ Links ]

Hrushovski, Benjamin. 2007. Prosody, Hebrew. Encyclopedia Judaica (Second Edition) 16: 595-623. [ Links ]

Joüon, Paul & Takamitsu Muraoka. 2006. A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. 2d edition. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute. [ Links ]

Köhler, Ludwig & Walter Baumgartner. 1994-1999. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. Leiden: Brill. [HALOT] [ Links ]

Kugel, James L. 1981. The Idea of Biblical Poetry: Parallelism and Its History. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Kurylowicz, Jerzy. 1972. Studies in Semitic Grammar and Metrics. London: Curzon Press. [ Links ]

Lowth, Robert. 1835 [1753/1775]. Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews. 3rd ed. Translated by George Gregory. London: Thomas Tegg. [ Links ]

Lunn, Nicholas P. 2006. Word-Order Variation in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: Differentiating Pragmatics and Poetics. Paternoster Biblical Monographs. Milton Keyes (UK) and Waynesboro (USA): Paternoster.

Miller, Cynthia L. 1996/2003. The Representation of Speech in Biblical Hebrew Narrative: A Linguistic Analysis. Harvard Semitic Monographs 55. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Miller, Cynthia L. 2008. Constraints on Ellipsis in Biblical Hebrew. In Cynthia L. Miller (ed.). Studies in Comparative Semitic and Afroasiatic Linguistics Presented to Gene B. Gragg, 165180. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, 60. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. [ Links ]

Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L. & Naudé, Jacobus A. 2015. The Participle and Negation in Biblical Hebrew. KUSATU 19: 165-199. [Papers from the 11th Mainz International Colloquium in Ancient Hebrew]. [ Links ]

Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L. & Naudé, Jacobus A. 2017. A Re-Examination of Grammatical Categorization in Biblical Hebrew. In Tarsee Li & Keith Dyer (eds.). From Ancient Manuscripts to Modern Dictionaries: Select Studies in Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek, 331-376. Perspectives on Linguistics and Ancient Languages 9. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. https://doi.org/10.31826/9781463237073-016 [ Links ]

Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L. & Naudé, Jacobus A. 2019. Differentiating Dislocations, Topicalisation and Extraposition in Biblical Hebrew: Evidence from Negation. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus 56: 179-199. https://doi.org/10.5842/56-0-832 [ Links ]

Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L. & Naudé, Jacobus A. 2021. Differentiating Left Dislocation Constructions in Biblical Hebrew. In Aaron D. Hornkohl & Geoffrey Khan (eds.). New Perspectives in Biblical and Rabbinic Hebrew, 617-640. Cambridge Semitic Languages and Cultures. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0250.20 [ Links ]

Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L. & Naudé, Jacobus A. 2022. Acrostic Style and Word Order: An Examination of Macrostructural Constraints and Local Syntax in the Acrostic Poem of Lamentations 3. In H.H. Hardy II, Joseph Lam, & Eric D. Reymond (eds.). "Like Ilu Are You Wise": Studies in Northwest Semitic Languages and Literatures in Honor of Dennis G. Pardee, 255-267. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. [ Links ]

Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L. & Van der Merwe, Christo H.J. 2011. Hinneh and Mirativity. Hebrew Studies 52: 53-81. https://doi.org/10.1353/hbr.2011.0017 [ Links ]

Naudé, Jacobus A. 1990. A Syntactic Analysis of Dislocations in Biblical Hebrew. Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 16: 115-130. [ Links ]

Naudé, Jacobus A. & Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L. 2017. At the Interface of Syntax and Prosody: Differentiating Left Dislocated and Tripartite Verbless Clauses in Biblical Hebrew. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 48: 223-238. https://doi.org/10.5774/48-0-293 [ Links ]

Naudé, Jacobus A. & Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L. 2023. Generative Linguistics as a Theoretical Framework for the Explanation of Problematic Constructions in Biblical Hebrew. In William A. Ross and Elizabeth Robar (eds.). Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text, 6-66. Cambridge University of Cambridge and Open Book Publishers. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0358

O'Connor, Michael. 1980. Hebrew Verse Structure. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Soll, William Michael. 1988. Babylonian and Biblical Acrostics. Biblica 69: 306-323. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, Christo H.J., Jacobus A. Naudé & J.H. Kroeze. 2017. A Biblical Hebrew Reference Grammar. 2nd edition. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Waltke, Bruce K. & Michael O'Connor. 1990. An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Watson, Wilfred G.E. 1984. Classical Hebrew Poetry: A Guide to Its Techniques. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement 26. Sheffield: JSOT Press. [ Links ]

1 It is a pleasure for us to dedicate this essay to Andries Coetzee, whose early work on Biblical Hebrew has made a profound contribution to our discipline.

2 The notion of parallelism as well as the characteristics and features of the poetic line are hotly debated aspects of Biblical Hebrew poetry. Lowth's proposal of semantic parallelism in 1753 as the chief organising principle of Biblical Hebrew poetry persists after more than 250 years (Lowth 1835:204-212). Counterevidence against the theory of parallelism as an explanation for the nature of Biblical Hebrew poetry has led to efforts for its defence (for example, Cross 1983:129-155) or for its replacement with a metric system (for example, Freedman and Von Frange 1996) or syntactic constraints (for example, Collins 1978, O'Connor 1980, Greenstein 1983, Holmstedt 2019 and Grosser 2021), whereas Kurylowicz (1972) argues for a combination of syntax and stress. Kugel (1981) argues that there is no poetry in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament - only a continuum from loosely parallelistic structures in prose sections to more rhetorical parallelistic devices in what is misleadingly labelled verse. Alter (1985:8) does not see the need for such drastic revisions of Lowth's notion of parallelism in order to describe biblical poetry. Hrushovski (2007 [1971]: 598-599) proposes a semantic-syntactic-accentual "rhythm" as the basis of biblical verse, which is based on a cluster of changing principles confined within the limits of its poetics, namely heterogeneous parallelisms with a mutual reinforcement so that no single element - meaning, syntax, or stress -may be considered as purely dominant or as purely concomitant. This approach (or some variant of it) is accepted by many scholars (for example Alter 1985). What is clear and uncontroversial is that Biblical Hebrew poetry is not structured by rhyme and metre, as is common in traditional Western poetry.

3 In referring to parts of the poem, we use first the chapter and verse reference of Lamentations (e.g. 1:1), a letter to refer to the line (e.g. 1:1a, 1:1b), and a lowercase Roman numeral to refer to the half-line (e.g. 1:1ai, 1:1aii). When a Hebrew example consists of an entire line, we indicate its division into half-lines with a double solidus (//). Our poetic lineation throughout is guided by the Masoretic accents and reflects the lineation of Biblia Hebraica Quinta 2004 in this passage. In addition to the Leipzig Glossing Rules, the following abbreviations are used to gloss the Hebrew: CSTR = construct (bound member of a noun phrased); NEG.EXIST = negative existential particle; PRO = independent subject pronoun; WIPFV = waw consecutive imperfective.

4 Common nouns with word-initial w- include the rare form wätäd 'son' (attested only in Gen 11:30) as opposed to the usual form yeled (< yald) attested elsewhere in Biblical Hebrew. The only certain common noun beginning with w- is the word wäw 'nail, peg', which is used only in the description of the curtains of the tent of meeting (e.g., Exod 26:32-37). Two rare nouns with possible Arabic and/or Persian origins are: wäzär (Prov 21:8) 'to be loaded with guilt' (Arabic etymology) and ward (Song 4:13) 'rose' (Arabic or Persian etymology). Proper nouns indicating a location, each with an Arabic etymology include: wddän (Ezek 27:19) and wahëb (Gen 36:39; Num 21:14). Proper nouns indicating a person usually have a Persian etymology (wayzätä' Esth 9:9; wanyá Ezra 10:36; wasti Est 1:9) or the etymology is unknown (wopsi Num 13:14; wasni 1 Sam 8:2).

5 The infinitive absolute regularly appears after, rather than before, an imperative or participle (Waltke & O'Connor 1990: 585); see also Gesenius, Kautzsch, and Cowley (1910: 342-343).

6 Hillers' (1974) brief study of the syntax of Lamentations reaches the same conclusion.

7 An object from the same triliteral root as the verb (a so-called cognate object) usually appears after the verb (e.g., 2 Sam 12:16; Isa 24:22; 35:2; 42:17; Ezek 25:15; see Gesenius, Kautzsch & Cowley 1910: 367), the usual position for objects in Biblical Hebrew.

8 We accept the majority viewpoint that the unmarked word order in Biblical Hebrew is verb-subject and not subject-verb.

9 The Masoretic accent (a medieval Jewish system for annotating the prosody of the biblical text) on the dislocated constituent is a conjunctive accent rather than a disjunctive accent, as would be expected (Naudé & Miller-Naudé 2017). However, the prosodic break between the dislocated constituent and the matrix syntax is clear in that the two constituents of the matrix sentence are joined with the maqqef (a horizontal line linking two graphic words into one prosodic word).

10 The word mar is ambiguous - the same form is used for the adjective ('bitter') and the stative verb ('it is bitter'). Either morphological interpretation is possible in this verse without changing the overall structure of a left dislocated construction. On the problem of differentiating adjectival forms and stative verbal forms from the same triliteral root, see Miller-Naudé and Naudé (2017).

11 The expression mar l- 'bitter to X' meaning 'X has a bitter (thing)' or 'X is bitter' occurs also in Ruth 1:13 and Isa 38:17.

12 Dobbs-Allsopp considers many of these unusual patterns to be varieties of poetic enjambment, "the continuation of syntax and sense across line junctures without a major pause" (Dobbs-Allsopp 2001a: 219; see also Dobbs-Allsopp 2001b).

13 Extraposition is a syntactic construction involving the movement of a constituent to the right boundary of a sentence. Extraposition is thus the mirror image of topicalisation, which moves a constituent to the left boundary of a sentence. For the differentiation of these constructions in Biblical Hebrew, see Miller-Naudé and Naudé (2019).

14 An anonymous reviewer suggests that the relative clause could be a headless relative clause ('that which you commanded...'), an analysis that is unlikely because it cannot be integrated syntactically into the larger context.

15 See, for example, Deut 1:39 and Judg 8:15 as mentioned by HALOT s.v. aser. This analysis is favoured by Holmstedt (2016: 340).

16 Holmstedt (2016: 113 n. 12) accepts the following examples of the entire sentence as the head of a relative: Exod 10:6; Deut 17:3; Josh 4:23; 2 Sam 4:10; Jer 7:31; 19:5; 32:35; 48:8; Esth 4:16; 2 Chr 3:1 and possibly Ps 139:15.

17 See Holmstedt (2016: 112 nn. 10-11): Gen 11:7; 30:18; Exod 29:33; Deut 4:19; 1 Kgs 3:12,13; 15:13; Isa 47:15; Ezek 16:59; 20:21; 47:14; Ps 31:8; 33:15; 103:2-5; 104:3; 113:5-6; 114:10; 147:8; Job 9:4-7; Eccl 5:15; 10:16, 17; Song 1:6; 5:2.

18 See, for example, Exod 5:16; Isa 5:20; 32:12; 40:19; Amos 6:4.